2

POE, POLITICS, AND THE PEACE GENERATION

THE 1960S BEGAN WELL for Roger Corman. His first Poe adaptation—a wide-screen psychological chiller photographed in eye-popping Cinemascope by Floyd Crosby, decked out with Daniel Haller’s sumptuously baroque sets, and starring a legitimate marquee attraction in horror icon Vincent Price—immediately put the filmmaker on a new plateau. House of Usher also made a mint at the box office for AIP. Naturally, Arkoff and Nicholson demanded sequels, stat. Corman would go on to produce and direct seven more Poe-inspired films over the next four years, including 1961’s The Pit and the Pendulum, 1962’s Tales of Terror and The Premature Burial, 1963’s The Raven and The Haunted Palace, and 1964’s The Masque of the Red Death and The Tomb of Ligeia.

In 1962, he also directed the most personal film of his career—The Intruder. The simmering, sensational drama about integration, starring William Shatner as a rabble-rousing carpetbagger who stokes the fears of a small Missouri town, was a passion project for the director, whose own liberal politics compelled him to tackle civil rights at a time when the topic seemed too hot to touch. When no studio, including AIP, would finance the film, Corman mortgaged his own home to get it made. For years, it was the only film he made that lost money. Yet it brought him a new wave of critical admirers.

By the middle of the decade, Corman seemed to sense earlier than most in Hollywood’s corner offices that the times were changing. He had surrounded himself with young and hungry filmmakers like Francis Ford Coppola, Monte Hellman, Jack Hill, Peter Bogdanovich, Nicolas Roeg, Robert Towne, Dennis Hopper, and Jack Nicholson. And as the first hints of the counterculture started to appear, Corman had the instincts of a divining rod and the acute business sense to put the new zeitgeist on celluloid. While the majors were still churning out hopelessly square, middle-of-the-road confections, he set his crosshairs on the sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll generation, making biker flicks about the Hells Angels (The Wild Angels) and psychedelic fantasias about LSD (The Trip). The sensibilities of Corman’s films from the era would eventually lead three of his regulars—Hopper, Nicholson, and Peter Fonda—to make 1969’s Easy Rider. That existential road movie’s roots traced back to Corman, who was all set to executive produce Easy Rider at AIP until Sam Arkoff balked at their insistence that the unpredictable and often short-tempered Hopper direct the film. The disagreement ended in strong words, with Fonda and Hopper storming out of Arkoff’s office. In the end, AIP and Corman would lose out on what would end up being the most successful—and influential—low-budget film ever made.

In the meantime, three thousand miles away at New York University, on a floor they shared with the Serbo-Croatian library, a young group of movie-mad film students (and a professor named Martin Scorsese) who had been weaned on Corman’s films dreamed of heading west to make their names. Roger Corman was about to summon them to a New World.…

Photo from the set of The Pit and the Pendulum (1961), directed by Roger Corman. Corman and his crew set up the climactic shot of his second installment in the Poe saga. Thanks to his trusted cinematographer Floyd Crosby and his ace production designer Daniel Haller, Corman managed to make the Poe films look every bit as rich and sumptuous as the movies coming out of the big studios. Eye candy on a budget.

U.S. poster from The Pit and the Pendulum (1961). Says Martin Scorsese, “With the Poe pictures, suddenly there was a personality emerging from the Corman factory.”

JOE DANTE (director; post-Corman credits include The Howling, Gremlins, and Matinee): “Roger was such an incredibly prolific director. And I really think he was a great filmmaker, way underestimated and undervalued because of the genre he was working in. I love Masque of the Red Death, I love The Intruder, I love Man with the X-Ray Eyes, I could go on. There’s an intelligence to his movies that is always light-years better than what the other guy did.”

MARTIN SCORSESE: “In the beginning of the sixties, especially with the Poe pictures, suddenly there was a personality emerging from the Corman factory. After House of Usher, in quick succession there was The Pit and the Pendulum and The Masque of the Red Death and The Tomb of Ligeia, which is my favorite. They all just took your breath away. All of a sudden, Corman had become a cult and was written up in Sight and Sound magazine.”

ROGER CORMAN: “I wasn’t paying too much attention to the critics, but it felt good when the Poe films were appreciated. I felt like I was making little films. I would be reviewed in Variety and the Hollywood Reporter and things like that, but I never really thought about it particularly until I started to get nice reviews on the Poe pictures. I started to pay a little more attention.”

Photo from the set of The Pit and the Pendulum (1961). Producer Sam Arkoff (with stogie in hand, naturally) has a dungeon-set discussion with Corman—the thoroughbred in AIP’s stable.

Production still from Tales of Terror (1962), directed by Roger Corman. Vincent Price strangles Basil Rathbone in Corman’s third Poe film. He probably should be more concerned with his melting face.

JOHN LANDIS (director; post-Corman credits include Animal House, The Blues Brothers, and An American Werewolf in London): “Look at his body of work as a director; there are some really good movies in there. As a kid, I adored the Poe films. I was ten or eleven when I saw The Pit and the Pendulum. It scared the shit out of me! The ending is amazing. The last shot is Barbara Steele in an iron maiden, and you kind of forget about her. And then they close the door to the pit, and they say, ‘This door will never be opened again.’ And then the CinemaScope screen suddenly squeezes down to just the eyeholes of the iron maiden, and you realize, ‘Oh, fuck! She’s still in there! Ahhhh!’ I’ve deliberately never seen that movie again. Not so much because it scared me, but because I know it couldn’t possibly be that good, you know?”

RICHARD MATHESON: “Roger would always tell me my scripts were too long and that I had to cut them down. So I’d cut them down. And then when they were shooting they’d call and say it was too short. That was frustrating. He gave me five percent of the profits in my contract, which I thought was generous. Of course, I never saw a penny from them. Eventually, I sold my percentage back for a low sum of money. And I found out recently that with all of the times they showed them on TV, I could have made a lot of money. By the time we got to The Raven in 1963, I couldn’t take them seriously anymore. I had to give it more of a comedic touch.”

Frame grab from The Pit and the Pendulum (1961). British beauty Barbara Steele can muster only a muffled scream as her fate is sealed, in one of Poe’s most devious plot twists.

Frame grab from The Raven (1963), directed by Roger Corman. Coachman Jack Nicholson takes a lovely lass for a midnight ride in The Raven, Corman’s attempt (some would say unnecessary) to add levity to the Poe series.

MARTIN SCORSESE: “After The Raven, which is really more of a Poe comedy, came The Terror. Now that is a film you can watch over and over again, and you never know what happened. I think he had five different directors on that picture.”

FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA (director; post-Corman credits include The Godfather, The Conversation, and Apocalypse Now): “With The Terror, Roger took the sets from another production he’d just filmed and a flimsy premise and quickly concocted to shoot some sequences starring Boris Karloff and Jack Nicholson. However, it made little sense, and so Roger kept trying to shoot footage that could fill out what he had and perhaps make a feature film out of it. I went for a while to see what I could do, along with Jack Nicholson and some other actors. I was very uncomfortable with the assignment and eventually left and was replaced by a string of others. I didn’t get Jack Nicholson. I felt he was very smart, but I didn’t grasp his style of acting. Obviously, I was wrong.”

U.S. poster for The Terror (1963), directed by Roger Corman. A mess from the get-go, this head-scratching gothic chiller stars Boris Karloff and had a Who’s Who of future directors taking a turn behind the camera, including Francis Ford Coppola, Monte Hellman, and Jack Hill.

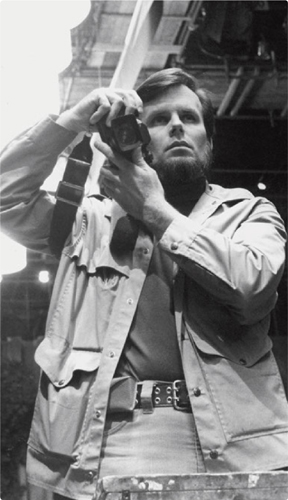

Photo of Gary Kurtz. Kurtz got his start in the business doing pickup shots on Corman’s unintelligible horror film The Terror. His career would pick up when he hooked up with George Lucas and became a producer on American Graffiti and Star Wars.

Still from The Terror (1963). Jack Nicholson and his off-screen wife at the time, actress Sandra Knight, share a scene for whatever director was unlucky enough to be on the set that day.

JACK HILL (writer, director; post-Corman credits include Coffy and Foxy Brown): “There’s a rumor that Jack Nicholson directed part of The Terror. I don’t know how that got started. To my knowledge, he didn’t direct anything. Roger had shot this script that Leo Gordon had written, which was not really a complete movie. It just had a lot of scenes in it of Boris Karloff. He shot, I think, three days with Boris on that. And then he hired Francis to write additional scenes that would fill it out and make some sort of story out of it. I was recording sound and doing various odd jobs on the picture, and we shot up at Big Sur. Some beautiful locations up there with Jack Nicholson and his wife at the time, Sandra Knight. The problem was when we got back and looked at the footage, you couldn’t make sense out of it. So Roger hired me to write the new script, which would use as much of the footage Francis shot as we could. And then he got Monte Hellman to direct what I had written. And then besides that, there were a lot of what we call ‘inserts’—little bits and pieces to make the whole thing fit together—which it didn’t have. And I shot those. We got a double for Boris Karloff who doesn’t look anything like him. And the water is pouring into the dungeon of this castle, and all the rocks from the castle set are floating in the water. It’s really funny.”

JACK NICHOLSON: “God forbid, I don’t want to encourage anyone to see it. I throw Dick Miller up against this door, and Dick Miller now tries to explain the entire picture in one speech. It’s the only film that I know of that has no story line that you can follow.”

FRANCES DOEL (writer, Corman script supervisor): “I began working for Roger at the end of 1964. I was at university at Oxford, and Roger was in England. He had just finished the last of his Poe pictures, The Tomb of Ligeia, and he put up notices at Oxford and Cambridge for an assistant. That was my first job. I had no inkling of what a producer was or did. I just didn’t want to go into the civil service, I wanted an adventure … and I found it. My initial impressions were that he was extremely intelligent and courteous and very businesslike. But I didn’t know who he was or what he had done. And I think it was my first day in the office, he showed me where the filing cabinet was, and I went through it and I saw all of these titles: Beast from Haunted Cave and Attack of the Giant Leeches. I thought, What on Earth is this?!”

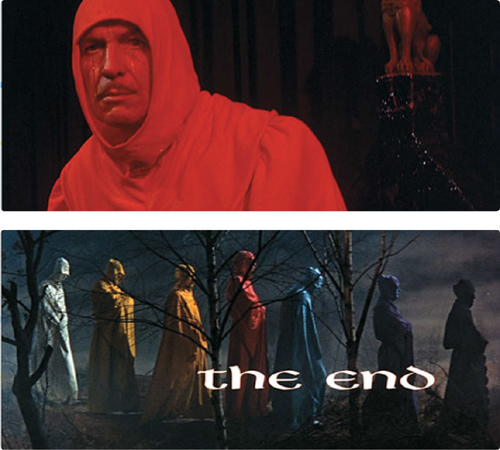

Frame grabs from The Masque of the Red Death (1964), directed by Roger Corman. Thanks to the lurid, rose-petal-rich cinematography of Nicolas Roeg (later director of Don’t Look Now and The Man Who Fell to Earth) and the use of left-over sets in England from bigger-budget studio films like Becket, Masque is Corman’s most poetic and haunting film. The bloody end will come soon enough for Vincent Price’s Prince Prospero.

Production still from The Tomb of Ligeia (1964), directed by Roger Corman. Corman and Vincent Price have a powwow about Poe—or perhaps just about groovy sunglasses.

Frame grab from The Tomb of Ligeia (1964). Vincent Price plays a twisted, obsessive widower in the closing chapter of Corman’s Poe cycle. Robert Towne’s kinky, psychologically layered script foreshadowed the kind of storytelling he would later become famous for with Chinatown.

HASKELL WEXLER: “I liked the Poe films fine, but Roger made a film about integration in the South around the same time called The Intruder. It got him into a lot of trouble. I remember talking to him about working on it because I had been shooting civil rights things, but the scheduling didn’t work out. When he told me the story, I thought, Wow, this guy has got buried in him something beyond just exploitation and making money!”

GENE CORMAN: “We wanted to make money—there’s not a question about that. But we also wanted to advance our careers. One of the most upsetting things that ever happened to me and to Roger was what happened with The Intruder. There was a strong possibility that this was going to be America’s entry at the Cannes Film Festival. But we were fucked by a major director who was on the committee. He said the Cormans make exploitation films. Nobody would have made that film except my brother. You have to believe in equality and school integration unless you’re a gorilla. Times were changing, but people weren’t changing. There was something wrong here in America! This is the land of opportunity, but you’re not giving opportunity to people who need some help. That was the reason we wanted to make it. It was an important film that was ahead of its time. And it’s the only film he ever made that didn’t make money.”

ROGER CORMAN: “I got a loan and I put up my house as collateral to get The Intruder made. I’ve always been on the liberal, if not radical, side of politics. I believed very much in the concept of integration, and I read the book by Charles Beaumont and thought this is an excellent idea for a picture, and it fit my political beliefs. It was something I wanted to do—I wanted to do a more serious film. I was happy to do horror films and science fiction, but I just wanted to move a little bit away. The movie cost about $80,000. I’d made seventeen or eighteen films, and I really had a great record. It got to the point where I could go to AIP or Allied Artists or any other small distribution company and any idea I told them, they would back me, because I’d never missed. I was really surprised that every one of them said no to The Intruder. I couldn’t believe it. They’d never said no to me before. So I thought, I’ll make the picture myself. And I made it, and my brother produced it and I directed.”

GENE CORMAN: “AIP thought it was too tough, and nobody else wanted it! So Roger put up his own money. When we started to shoot that film in Missouri, the last thing I was going to do was have anyone read the script. There’s a great scene in the film where Bill Shatner harasses the crowd with an anti-black speech. Roger and I decided that Bill would just mouth all of his lines. Roger told all the extras that Bill had a sore throat and he pantomimed the lines so they wouldn’t know what it was all about. You should have seen the reaction when it came out. We were called Communists and anti-American—people were going to kill us! They thought we were everything that the Klan would have loved to set on fire.”

WILLIAM SHATNER (actor; post-Corman credits include Star Trek): “The Intruder was Roger Corman’s best movie and his only loss. Roger had to make sure that no one killed us, because the film was about integration and we were in a part of the country that emphatically did not want to integrate. I didn’t know about his films like Attack of the Crab Monsters. All I knew was that this was a great story and a terrific part. He never told me why he wanted me for the part, but I’m sure it was because I was handsome, brilliant, and didn’t need the money—because he didn’t pay me! One night we were shooting a white-supremacy parade in the black part of town, and someone was knifed in the crowd. That shoot seemed to go on forever. It was very tense. I was glad to get out of there in one piece.”

ROGER CORMAN: “We shot it in Missouri, and we had death threats. But we made the film and released it, and it got wonderful reviews. It won a couple of minor film festivals.

Frame grab from The Intruder (1962), directed by Roger Corman. William Shatner cruises for trouble with a carful of Klansmen in Corman’s incendiary film about segregation.

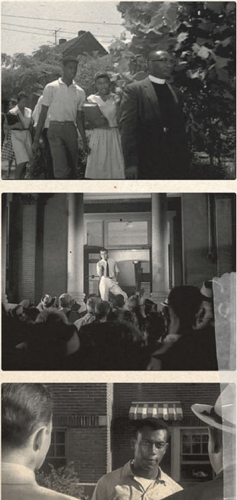

The Intruder 1962

The Intruder is best known for being the only movie that Roger Corman ever lost a dime on. Which is saying something, since he directed and produced four hundred of them. But that claim to fame only tells part of the story. After all, the white-hot 1962 integration drama is not only Corman’s most passionate statement of his own bedrock political beliefs, it’s the movie that broke his heart.

Based on Charles Beaumont’s 1958 novel, the black-and-white film was shot in Sikeston, Missouri. Like so many other parts of America at the time, the area was a tinderbox, opposed to the idea of the mixing of the races. This was before the murder of Medgar Evers, before Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I have a dream” speech. Corman, who has always been quick to describe himself as a radical dressed in country-club clothing, had been itching to break out of the genre filmmaking ghetto and make an important picture. When Beaumont’s novel landed in his hands, Corman’s chance to say something deeply personal—and perhaps also finally earn some respectability—came into focus. When no studio would back the project, he put up the money himself, mortgaging his home to cover the film’s $80,000 budget, and headed off to Sikeston, where he and his crew would be threatened and nearly run out of town.

Frame grab from The Intruder (1962). Shatner rolls into town looking like a cool cat in sunglasses, but beneath the surface is a rabble-rouser simmering with hatred and bile.

William Shatner, a handsome Canadian Broadway actor who was still years away from cementing his fame as Star Trek’s Captain Kirk, was cast as Adam Cramer—a smooth-talking, charismatic carpetbagger in a white linen suit who arrives in the sleepy town of Caxton on the eve of integration. Black students are about to be admitted to the town’s high school, and the community is none too pleased about it. Cramer arrives spewing hate speech and bile from the steps of town hall, wrapping himself in the American flag and threatening that “this little town’s gonna burn!” He’s like a more venomous version of Robert Preston’s Harold Hill in The Music Man. And he finds an all-too-willing audience to turn his veiled words into firebombing deeds.

It’s easy to look at a film like The Intruder now—in America’s so-called “post-racial” age—and dismiss it as just another unwelcome reminder of our ugly past. But Corman’s film still feels as morally urgent today as it did fifty years ago. It may be the most unflinching portrait of race in the South ever put on celluloid, an achievement that’s even more remarkable when you consider that it took the head-in-the-sand Hollywood studios another five years to even approach the topic (and with kid gloves), in 1967’s In the Heat of the Night and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. If you’re the kind of moviegoer who’s always dismissed Corman as merely an exploitation filmmaker, The Intruder will show you something quite different: a socially committed artist of bold power and true force. It went to the Venice Film Festival. One newspaper said, ‘This film is a major credit to the entire American motion picture industry.’ But it was the first film where I lost money. You can’t call them right every time. But The Intruder sort of stuck with me because it was the first time I ever lost.”

Terrified students dare to cross the color line; Shatner spews racist rhetoric from the steps of town hall; Charles Barnes stares down a pair of bigots.

Cigarettes may be dangerous for your health, but they’re nothing compared to Shatner’s slick agitator Adam Cramer.

Frame grab from The Intruder (1962). Roger and Gene Corman were nearly run out of town while making the film. “We were called Communists and anti-American—people were going to kill us!” recalls Gene. “They thought we were everything that the Klan would have loved to set on fire.”

FRANCES DOEL: “I do think Roger cared very much about his reputation as a director. There was a retrospective of his films at the Cinémathèque in Paris, and there were reviews of some of his movies and an essay about him that he asked me to translate. And the first question he asked me was ‘Do they say I’m superficial?’ I think he cared very much. I think the failure commercially of The Intruder, which he really believed in, really got to him. Until that point, I think he thought that he would get better and better as a director, and his films would get better and better. And I think he probably believed that The Intruder was an attempt to make a serious film, and I think it was a devastating blow to him that it did not work for him. I suspect from that point on, he decided: I’m going to make a lot of films and it’s a business, I’m just going to go on.”

JOHN LANDIS: “The Intruder was a ballsy picture to make at the time. And because it made no money, that’s what he equates … . You know, I remember when I met Martin Scorsese the first time, I told him that I thought King of Comedy was brilliant. And he said, ‘Ah, it didn’t make any money. It was terrible.’ And he was quite serious; he didn’t want to talk about it. It was painful. And I thought, Yeah, it might not have made money, but it’s a brilliant fucking movie. He wouldn’t even hear it. I get the sense that’s probably how Roger felt about The Intruder.”

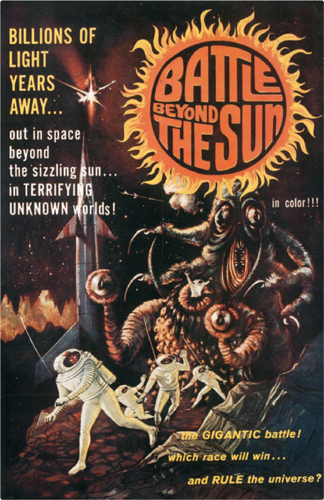

JACK HILL: “I was in the cinema department at UCLA with Francis Coppola, and we worked together on some student films. I actually had worked with Francis on some nudie films he made, like The Bellboy and the Playgirls. I’m not ashamed to admit that. It was something to do. And then Francis went off to work for Roger, and I followed him. Roger had a great knack for finding talented people who were willing to work for practically nothing and would do anything to get going. He was the only game in town for that. You could only work in a major studio if you were somebody’s son—not even their daughter. And the unions had iron control. In those days, the projectionist wouldn’t show a movie if it wasn’t union. Roger would go to UCLA and ask around about who the most talented students were. One of the first things Francis and I did for him was Battle Beyond the Sun. It was a Russian science-fiction film. The Soviet Union at that time was spending a lot of money on science-fiction movies, to make the Soviet Union look glorious, and they didn’t have to worry about budgets. They could just put in whatever they wanted. So they had a lot of really terrific special effects on it. Guys in space suits. So Roger had the idea to use as much footage from that movie as he could, where you couldn’t see the actors’ faces, and then to double them with American actors that Roger would shoot. We made up a story to use that footage. And we went out and shot a whole lot of scenes to put it all together. It was fun. It was problem-solving.”

U.S. poster for Battle Beyond the Sun (1963), directed by Francis Ford Coppola. Corman hired Coppola straight out of film school to be his guy Friday. One of his earliest assignments was cutting action scenes out of a Russian sci-fi film called Nebo Zovyot and padding them with American inserts.

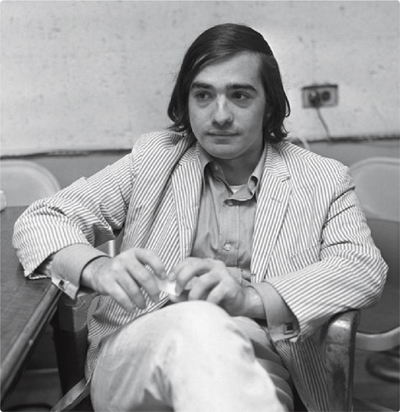

Photo of Francis Ford Coppola in 1966, shortly after leaving the University of Corman and graduating to the major studios, where he would earn wealth, fame, and Oscars galore with the Godfather films, The Conversation, and Apocalypse Now.

FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA: “I became Roger’s assistant and functioned as a jack-of-all-trades. I tried to make myself as indispensable as possible and eventually traveled with him to Europe for the production of 1963’s The Young Racers as the sound man.”

MENAHEM GOLAN (producer; post-Corman credits include Death Wish II, Runaway Train, and Over the Top): “I was studying film at City College in New York, and I heard that Roger Corman was going to Europe to make a film called The Young Racers. I wrote him a letter asking if I could work on it for free. He wrote me back, saying, ‘If you buy a car and come to Monte Carlo, you can be my driver.’ I bought a secondhand car in Paris and drove to Monte Carlo. And there he was. He introduced me to the soundman, Francis Coppola. I asked Francis if he had ever done sound before. And he said no, but he had a how-to book to learn from. Roger asked me to find a wreath to put on the winner of the car race in the movie. It was late at night, and I had to go all over town before I found a florist at his home and had him make me a wreath. I almost got arrested. When I came to the set the next morning with the wreath, Corman said to the whole crew, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, this young man will be a producer!’ And he was right.”

U.S. poster for The Young Racers (1963), directed by Roger Corman. On what was conceived as a free-wheeling working holiday, Corman and his crew—including Francis Ford Coppola and Menahem Golan—headed to Europe for this high-speed adventure starring Mark Damon, William Campbell, and Luana Anders. Coppola would stay behind to make his next film, Dementia 13.

U.S. poster for X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (1963), directed by Roger Corman. Ray Milland stars as Dr. James Xavier, a scientist who conducts experiments on himself with decidedly mixed results. Sure, he can see through women’s clothing, but at what price?

FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA: “Knowing that Roger often made use of one film’s equipment and personnel for a second production right afterward, I wrote the basis of the script for 1963’s Dementia 13 and showed it to him. When it turned out that he had to return to L.A. in order to make another film, my gamble paid off, and I was given the chance to take the equipment and direct the script in Ireland.”

MENAHEM GOLAN: “One night, I was having dinner with Francis and Roger, and I told Roger about a movie I wanted to do in Israel. He asked me how much money I needed. I said $30,000. And he agreed. Then Francis jumped up: ‘Roger, are you fucking crazy?! Give me $30,000, and I’ll give you an American movie!’ He told Roger he would have a script for him to read the next morning. And all night long, since Francis was in the room next to me, I heard his typewriter tapping away furiously. He wrote that script in one night. That’s how Francis stole my $30,000 and went to Ireland and made Dementia 13. And then Francis had the guts to ask me if I wanted to be his assistant on his film!”

Production still from X: The Man with the X-Ray Eyes (1963). Ray Milland discovers the irony involved in becoming his own guinea pig.

U.S. poster for Dementia 13 (1963), directed by Francis Ford Coppola. Corman thought he might have the next Psycho sensation on his hands when he backed (and then tried to back out of) Coppola’s chiller. Needless to say, it didn’t pan out that way.

FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA: “After the big hit Psycho, there had been other imitations, including William Castle’s Homicidal. I was supposed to make Dementia 13 a knock-off of that. Roger had given me $20,000 to make the film. When I went to Ireland, I met an English producer who became interested and gave me $20,000 more for the U.K. rights. When I called Roger to tell him, thinking he’d be pleased, he wanted me to send the $20,000 he had given me back, so he would get the film for nothing. But I added the second investment to the original and made the film for $40,000. Given the quick schedule and tiny budget, I feel the film turned out OK.”

GARY KURTZ (producer; post-Corman credits include Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back): “One of the first films I worked on was Francis’s Dementia 13. He had shot the film in Ireland. Then after the film was shot and being edited, Francis was off doing something else, and Roger didn’t think that Dementia 13 worked completely well, and it needed some kind of introduction. So I was part of the crew that shot this opening scene for Dementia 13, which is really just an actor pretending to be a psychiatrist talking about dementia. It just padded out the film a little bit.”

JACK HILL: “Francis was only finished with about two-thirds of the film. So I had to do a lot of filling for that and write more material and pad it out. It was released with The Terror on a double bill. When we went to the previews with an audience, they really loved Dementia 13. I think it was more of an attraction than The Terror at the time.”

U.S. poster for Blood Bath (1966), directed by Jack Hill and Stephanie Rothman. Beatniks, vampires, and beautiful women being lowered into vats of boiling wax—sounds like a Jack Hill film, all right.

GARY KURTZ: “One of the others I did sound on was Blood Bath, which was a kind of infamous one. Roger had a deal with a Yugoslavian filmmaker. And the film was made in English in Yugoslavia. He decided it needed to be juiced up with more gore and horror. William Campbell played the lead in that one—he played a demented artist who killed his models and kind of melted them down in a vat or something. It still wasn’t really good enough to release theatrically, so we did another version where I was the cameraman and added more stuff. But William Campbell was no longer available, so this time the script turned him into a vampire, and we hired another actor who looked vaguely similar. It was an odd way to make movies. I remember there was a sign in the production office that said, ‘There’s never enough time to do it right, but there’s always time to do it over.’ ”

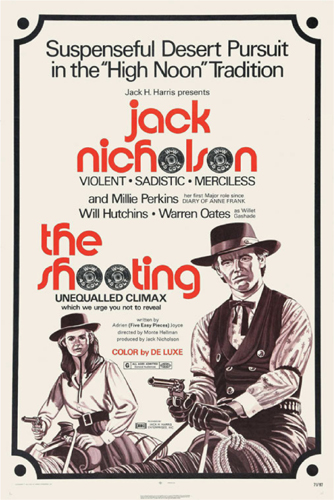

MONTE HELLMAN: “Roger had agreed to finance a movie that Jack Nicholson had written called Epitaph. Well, Jack and I had just gotten back from making two movies in the Philippines together—1964’s Back Door to Hell and Flights of Fury—and Roger changed his mind. So, as a kind of consolation prize, he said that we could make a Western. And then he said, ‘As long as you’re making one, you may as well make two.’ Those became Ride in the Whirlwind and The Shooting. Jack was getting work writing scripts, but from the first second I met him, I thought of him as a movie star. And I think Jack, in his mind, already was a movie star. He didn’t need to have any more proof. I liked those two Westerns we made a lot.”

U.S. poster for Ride in the Whirlwind (1965), directed by Monte Hellman. Jack Nicholson plays a cowhand who’s mistaken for an outlaw in Hellman’s underrated and underseen Western. It may be hard to fathom now, but Nicholson was making a better living as a screenwriter than as an actor at the time.

U.S. poster for The Shooting (1966), directed by Monte Hellman. After giving them the funds to go off and shoot Ride in the Whirlwind, Corman told Hellman and Nicholson, “As long as you’re making one, you may as well make two.”

GARY KURTZ: “I worked on both Ride in the Whirlwind and The Shooting with Monte in 1965. We carried the equipment around Utah on horseback. I thought Jack was great in those films. The camera loved him. The problem was Warren Oates and Jack worked in entirely different ways. Jack is a really intuitive actor, and he does his best work on the first two or three takes. If you do more than that, he’s kind of struggling a little bit to keep up the energy. Whereas Warren needed lots of rehearsal, and he builds slowly to it. So we got to the point on The Shooting where we would rehearse Warren with a stand-in, and then after that got settled we’d bring Jack in. Years later when I was doing The Empire Strikes Back, Jack was in London working on The Shining with Stanley Kubrick. And we would talk all the time at the studio. He was really frustrated with Kubrick’s way of working, where he just would keep shooting over and over and over again without telling anybody anything. In fact, Jack threatened to quit. After the Westerns, I worked on Queen of Blood and Voyage to a Distant Planet—I think that was the title. Who can remember? Anyway, Roger basically bought these sci-fi films from the Soviet Union, and we ran through all the footage and picked shots we could use. The spaceship shots were very good, but the stories in those films were pretty terrible. But if it was seventy-eight minutes long, it didn’t matter what it was about, he would buy it.”

U.S. poster for Queen of Blood (1966), directed by Curtis Harrington. John Saxon, Basil Rathbone, and Dennis Hopper meet a foxy green alien queen (Florence Marly) who has “an inhuman craving.”

Frame grab from Queen of Blood (1966). The fetching Marley quickly became a favorite of faithful readers of Forrest J. Ackerman’s Famous Monsters magazine like Joe Dante.

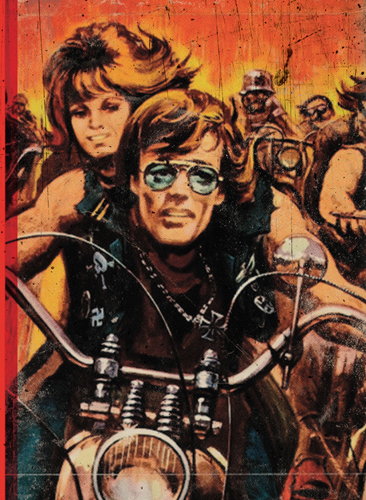

ROGER CORMAN: “As the Poe pictures went on, I felt like I was starting to repeat myself. It was time to move on. AIP wanted me to do more, and I said no, I want to do something in the streets and something contemporary. I suggested the Hells Angels, and they agreed. I hung out with the Angels at some of their parties. They were pretty wild. I only felt out of place once. Chuck Griffith and I brought marijuana to the parties, so we were always welcome. You know, you walk into some party and you look around and you see the best-looking girl, and you go over and start talking to her. Which I did. And Chuck came over to me at this one party and took me aside and said, ‘That girl you’re talking to is the old lady of the president of the Hells Angels, and he’s not too happy!’ You’ve never seen anybody walk away from a girl as fast as I did! I never said another word to her! We based the whole script of The Wild Angels on things they told us—even though I think they embellished some of their stories.”

The Masque of the Red Death 1964

By 1964, Roger Corman’s big-screen cycle of Edgar Allan Poe adaptations had become a license to print money for his patrons at American International Pictures. After cranking out six baroque Poe films in three short years, beginning with 1960’s House of Usher, Corman ventured to the other side of the Atlantic for his seventh and penultimate Poe flick, 1964’s The Masque of the Red Death. The trip paid off in what is arguably the best installment in the series, thanks to one of Vincent Price’s more nuanced performances, sumptuous candelabra-festooned design by Daniel Haller, and eye-candy cinematography courtesy of future auteur Nicolas Roeg (The Man Who Fell to Earth). Although Corman’s budgets were more lavish on the Poe films than on his less-prestigious AIP genre assignments, he got tremendously lucky when he arrived in England. The lavish medieval sets that had been constructed for a pricey pair of period epics, Becket and A Man for All Seasons, were still standing. With that bit of good fortune—and Corman’s undeniable knack for recycling—Masque delivers the ritziest production values of all the Poe chapters.

Price, who by this point had become Corman’s muse of the macabre, stars as Prince Prospero—a sadistic dandy with a sweet tooth for Satanism and a mustache-twirling villain of the first order. Certainly he has reason to be on edge. The Red Death has broken out across Europe, and a mysterious man cloaked in a crimson cowl foretells doom. No sooner does the spectral, Bergmanesque figure warn the downtrodden villagers that “the day of deliverance is at hand” than Prospero arrives to terrorize them and take a local beauty named Francesca (Jane Asher) back to his castle as both captive and conquest (making her remove the crucifix from around her neck first, of course). The outbreak of plague threatens Prospero’s power, so he holes up behind his fortified walls with his black magic–obsessed lover (Hazel Court) and a slew of decadent guests, whom he humiliates and taunts like a spoiled schoolchild. The most debauched—and enjoyable—guest of all is Alfredo (Patrick Magee), who takes one look at Francesca’s virgin alabaster skin and can think of nothing other than corrupting her.

After lapsing into broad comedy with 1963’s The Raven, The Masque of the Red Death was not only a return to deliciously dark form for Corman, it also one-upped all of the Poe films that had come before it. Corset-straining sensuality, swashbuckling action sequences, a deep dive into the velvet darkness of the occult, it’s all presented here in Pathécolor splendor. As for the finale of the film, it’s a master class in mood, as Prospero’s climactic masquerade ball brings him face to face with the mysterious crimson-cloaked figure. Prospero sees the apparition across the room and is transfixed. He believes he is finally meeting his master, the Prince of Darkness. But when this guest is finally unmasked, Prospero sees his own face reflected back at him, dripping in blood.

Production still from The Masque of the Red Death (1964). Please allow me to introduce myself … Vincent Price (far right) and Jane Asher (center) come face to face with Death in Corman’s Bergman-influenced Poe masterpiece.

U.S. poster for The Wild Angels (1966), directed by Roger Corman. Corman and writer Charles B. Griffith hung out with the Hells Angels to research the first of many successful outlaw biker pictures. This one packaged a pair of Hollywood offspring with famous last names (Peter Fonda and Nancy Sinatra) that clicked with ticket buyers.

DICK MILLER: “Roger somehow had a sixth sense. I don’t know if it was all his own, or if he was getting inside information from somewhere. He just seemed to know what the pulse of the country was, and he pounced on it.”

FRANK MARSHALL (producer; post-Corman credits include Raiders of the Lost Ark, Poltergeist, and Back to the Future): “My dad was in the music business as a composer and a guitar player, and he knew John Ford very well. I was invited to one of John Ford’s Christmas parties, and his whole stock company was there: John Wayne, Ward Bond, Harry Carey Jr. It was fantastic. There was this twenty-seven-year-old guy named Peter Bogdanovich sort of holding court in the middle of the room. I went over and met him, and we started talking. He said he was a film critic for Esquire magazine. He knew more than there was to know about movies. He knew he wanted to be a director. And he was excited because this fellow named Roger Corman, who I had never heard of, was giving him a chance to direct second unit on a movie called The Wild Angels. I told him if he needed any volunteers to give me a call.”

PETER BOGDANOVICH (director; post-Corman credits include The Last Picture Show, Paper Moon, and What’s Up, Doc?): “I wasn’t a particular fan of Roger’s movies. I don’t like horror movies. Some of the Poe films were elegantly done, but I wasn’t an expert on Roger Corman. In the middle of 1964, my wife Polly Platt and I drove across the country and moved to Los Angeles. One night, we went to see a movie—Jacques Demy’s Bay of Angels—and Roger and Robert Towne were sitting behind us. Roger told me that he had read my stuff in Esquire and asked if I would be interested in writing for the movies. Not long after, he asked me to write a script for a big adventure picture set in Poland—like The Bridge on the River Kwai, but cheap. I guess he had made some sort of deal in Poland. He rejected all of my and Polly’s ideas. Then he told me he was preparing to shoot a movie called The Wild Angels and asked me to scout locations with him. After that, he offered me $300 to rewrite the script for him. Well, I guess he was happy with it because he then asked me to be his assistant on the picture.”

BRUCE DERN (actor; post-Corman credits include Silent Running, Family Plot, and Big Love): “I first met Roger in 1966. Just on an interview. My agent said, ‘Roger Corman wants to see you.’ And I didn’t know much about Roger Corman. I wasn’t a big Cormanite or anything. I was just struggling to make a living. I went in and met him, and he told me that he remembered seeing me in a play on Broadway, The Shadow of a Gunman, in October of 1958, which was my first Broadway play. I was on stage fifty-two fucking seconds, so I have no idea how he remembered me! Anyway, that was for The Wild Angels. My wife at the time was Diane Ladd, who’s Laura’s mother. She was out in the car or something, and I said, ‘You know, my wife’s an actress,’ and she came in. He put us both in the movie.”

Photo from the set of The Wild Angels (1966). Corman gives Peter Fonda his motivation, while a young Peter Bogdanovich looks on.

Photo from the set of The Wild Angels (1966). Corman and Bruce Dern between takes—and, in Dern’s case, between showers.

Frame grab from The Wild Angels (1966). Real-life couple Bruce Dern and Diane Ladd play the hard-living Loser and Gaysh.

DIANE LADD (actress; post-Corman credits include Chinatown and Wild at Heart): “When I went in, Roger said, ‘You’re too young to be married to Bruce Dern.’ He gave me the part of the biker girl, Gaysh. It was my first movie. One day, Roger had us all ride really fast on motorcycles on a dirt road, which was very dangerous. In the industry, stunts like that are called ‘special business.’ And I didn’t get paid extra for that. When my check came, I said, ‘Wait a minute, where’s my special-business money?’ And Bruce said, ‘Oh, he’s not going to pay you special business.’ I said, ‘I risked my life, what do you mean?’ So when the movie was over, I filed a lawsuit against Roger at the Guild. Bruce said, ‘If you file that, you will never work for him again.’ I said, ‘Let me tell you something. Roger Corman is a man who respects people who stand up for their rights, and he respects money. And he will only respect me for this.’ Bruce said, ‘You’re out of your mind.’ But I did it, and Roger laughed like hell and paid me.”

PETER FONDA (actor; post-Corman credits include Easy Rider and Ulee’s Gold): “When Roger first said he wanted to make a movie about the Hells Angels, he said he didn’t want to make a statement with it. And I thought, ‘Oh, wow. Any time you make a movie about the Hells Angels, you’re making a statement.’ I ended up playing the lead in The Wild Angels and it was my breakout.”

PETER BOGDANOVICH: “Roger called just before he was supposed to start shooting and said, ‘George Chakiris doesn’t like the script. He was supposed to play the lead, and he dropped out. He says the script is immoral. Now what do we do?’ He had Peter Fonda cast to play the part that Bruce Dern eventually played. Peter was already set. So I said, ‘Well, maybe we could bump Peter Fonda up to the lead.’ And Roger said, ‘Let’s have him come in; why don’t you come meet him with me?’ Peter came in wearing aviator glasses and a leather jacket, and at one point he took off his glasses to clean them, and put them back on and left. Roger turned to me and said, ‘What do you think?’ And I said, ‘I think if he keeps his glasses on through the whole picture, we’re all right. Don’t let him take his glasses off, he looks weak when they’re off.’”

Advertisement for The Wild Angels (1966). “Wanted! For Violence … Hate … Riot!” The hard sell on the back of a Harley.

Photo of Peter Fonda and his sister Jane at the Paris premiere of The Wild Angels (1966). Sis may have been a bigger star at the time, but that would all change with Easy Rider.

BRUCE DERN: “Roger treated the Hells Angels with the utmost respect. What struck me about them was they were men of their word. And a lot of them had been either in Korea or were about to go to Vietnam. They were patriots. Roger was only paying these guys $10 a day for the actor, the machine, and his old lady. So he was getting two human beings and a motorcycle for ten bucks. We did the movie in ten days. I had a second unit sequence, where I had to steal a policeman’s motorcycle and take off on it. And that entire sequence was directed by Peter Bogdanovich. It wasn’t just the people in front of the camera who were learning. On The Wild Angels, Bogdanovich was riding in a sidecar shooting second unit, and Francis Coppola was also behind the camera. John Landis was an extra in the graveyard scene. We were all thrilled to be there—thrilled to be able to go to the University of Corman. None of us realized that’s where we were, but that’s where we were.”

PETER BOGDANOVICH: “At one point during the movie there was a fight scene between the Hells Angels, who were real Hells Angels, and some townies. We didn’t have enough townies, so Roger said to me, ‘Run in there.’ I ran in there, and within seconds I was down on the ground. They were kicking me. I was bleeding from ear to ear. Anyway, we kept falling behind, and finally Roger was fed up and said, ‘We’re wrapping tomorrow.’ And I said, ‘Roger, you’ve got so much of the script left to shoot.’ He goes, ‘Second unit will do that.’ I said, ‘Who’s gonna direct second unit?’ He said, ‘It doesn’t matter who directs the second unit. My secretary could direct the second unit! You could direct the second unit! Anybody can direct the second unit!’ I said, ‘Well, I’d love to.’ It was an amazing learning experience. It was the first big hit counterculture Hollywood movie, and it sort of started the New Hollywood.”

Frame grab from The Wild Angels (1966). Peter Fonda and Nancy Sinatra are the leather-clad leaders of the pack.

BRUCE DERN: “One of the most disappointing things I’ve experienced in this business is the fact that Roger never got a chance to direct a big-budget motion picture. The most money they ever gave him to do a movie was 1967’s The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, and even that, he had to use all of the Fox contract players, like George Segal. But he did this wonderful thing for Jack Nicholson and me, which was he gave us bit parts in that film. Roger made sure that we each worked a day in the first week, and a day in the last week, so we got paid for five weeks. That was about the nicest thing anybody had ever done for me. Jack wasn’t around when we made The Wild Angels. But the next year, I made a movie called Rebel Rousers with Jack. That’s when I really started to get to know him. We were shooting at Paradise Cove in Malibu, and one day I walk by Jack, and he was sitting on this big rock, writing. I said, ‘What are you doing?’ And he says, ‘I’m writing a script for a movie called The Trip.’ I think Roger saw him more as a writer than an actor. I remember he showed me a page or two of the script, and I thought, Shit, this guy can write!”

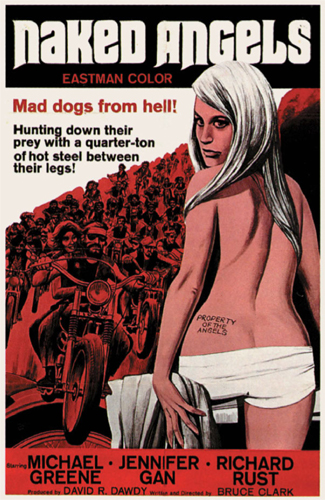

U.S. poster for Naked Angels (1969), directed by Bruce D. Clark. The Corman promotions team starts to hit their sensationalistic stride on the one-sheet for yet another installment in the producer’s hand-over-fist biker canon. “Mad dogs from hell! Hunting down their prey with a quarter-ton of hot steel between their legs!”

U.S. poster for Devil’s Angels (1967), directed by Daniel Haller. Another titillating tale of two-wheeled rebellion, starring John Cassavetes and Mimsy Farmer.

JACK NICHOLSON: “Roger knew I had taken acid, and we were both serious on the subject. Both of us had tripped in kind of clinical situations. I told him that I didn’t want to write a flat-out exploitation film. He had higher aspirations this time. Roger was my whole bottom-line support then. I had done the Westerns, but I had pretty much given up as an actor. I really didn’t have much else going then, kind of a journeyman troubleshooter. He knew he couldn’t get a writer as good as me through regular ways. I was happy to write it and make a more demanding picture out of it. … I wrote the lead for Fonda, and I knew he and Dern, who did Rebel Rousers with me, had done the biker film. I hoped to get the part that Dern played—the guru. But I knew—from Wild Angels and The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre—that Roger always preferred Bruce.”

Lobby card for The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre (1967), directed by Roger Corman. Corman gets to shoot a gangster film for a major studio, but still manages to sprinkle a few familiar faces into the scenery (like Dick Miller, far right).

PETER FONDA: “Roger had great confidence in Jack. Roger liked his work, and he knew Jack was creative, otherwise he wouldn’t have hired him to write The Trip. Jack would give me pages—I’d go over to his place in Laurel Canyon and I’d sit there and say, ‘This is great, you’re right on it!’ Other people had tried to make movies about LSD, but this was perfect.”

BRUCE DERN: “Roger said he took a trip at Jack’s insistence. I don’t know if that meant Jack was there or what. But he said his trip lasted about six hours, and his face was never more than a foot off the ground. And he was just looking in the earth. And he saw villages in the earth. Whole villages with all kinds of stuff going on. And I said, ‘Yeah, well, that’s enough for me. I don’t need to know any more. I don’t need to take acid.’ I didn’t know Jack to be an LSD guy. Jack was a marijuana guy and an Irish whiskey guy. I’ve seen him incredibly stoned, but as lucid as anyone as you’ve ever known while in that condition.”

Photo of Roger Corman directing The Trip (1967). Screenwriter Jack Nicholson was no stranger to the subject or the substance, but Corman went to Big Sur to experiment with LSD to research his celluloid exploration of the paradise and perils of taking acid.

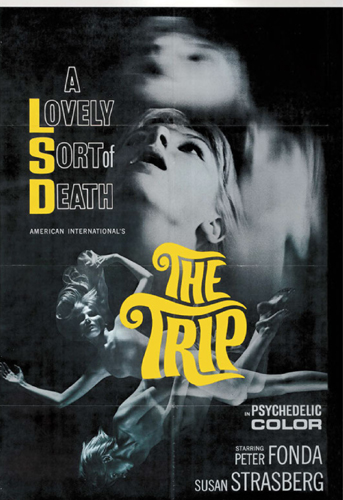

U.S. poster for The Trip (1967).

ROGER CORMAN: “If I was going to direct The Trip, I figured I had to actually take an LSD trip. I wasn’t nervous. The government was putting out a lot of propaganda about how dangerous it was. Even then, I felt that these are just statements from the government.”

FRANCES DOEL: “Roger instructed me to read The Tibetan Book of the Dead and summarize it for him—he thought it was essential research for the various stages of the psychic journey he was about to experience. I was instructed to take notes on his LSD trip. We went up to Big Sur—Roger, Chuck Griffith, Sharon Compton, who worked for Roger in the art department, and a couple of other people. Roger stayed at the Big Sur Inn. The rest of us camped out. It was the sixties, and we had VWs. I don’t know where they got the LSD, but I think Roger’s trip went very well for him. I know it did for me. It was one of those classic ‘Oh, my goodness, everything’s breathing’ experiences! The grass, the sun with flames coming out, but it wasn’t frightening. I wasn’t surprised that Roger wanted to do it. Just like I wasn’t surprised that before The Wild Angels, he wanted to meet the Hells Angels. I think it was clear to me he was a very hands-on researcher.”

ROGER CORMAN: “I had a wonderful trip. It was spectacular. I read Timothy Leary’s book where he talked about the set and the setting—to be with people you knew in a beautiful place. So I went up to Big Sur with a few friends. I was the straightest guy in a fairly wild crowd. And when people found out I was dropping acid, a lot of other people said, ‘If Roger’s doing it, we can do it!’ And it ended up there was a caravan going to Big Sur! We thought you had to have one person who was not taking a trip just in case something happened. You had to work out the equivalent of a shooting schedule—who would take a trip at which time and who would be the straight person with him. And my trip was so great, I had to talk to other people who had bad trips before I shot the movie, because I felt if I just based the picture on my trip alone, it would be an ad for LSD and how wonderful it is. So we integrated a few bad trips into the film. When I came down, I thought, I’m going to do this regularly, it’s wonderful. For one reason or another, I never did it again.”

DENNIS HOPPER (actor/director; post-Corman credits include Blue Velvet, Hoosiers, and True Romance): “Peter was starring in The Trip, and Bruce Dern and I had parts. Nicholson’s screenplay had a lot of description of acid trips, and we figured that Roger wasn’t really clued in to that, so he let Peter and me borrow some cameras and film, and we shot some of the acid trip scenes on the weekend. Roger said, ‘Go ahead and do it, try your hand at it!’ He made me believe I could direct.”

PETER FONDA: “I said, ‘Come on, Dennis. This is our chance, let’s do this!’ And I told Roger I had a camera—which I didn’t, of course—and we drove in Dennis’s Land Rover to the sand dunes in the central valley past the Salton Sea. It was cool stuff.”

DENNIS HOPPER: “Roger’s such an intelligent man, he was like a professor at a university. He always put his finger on the right thing. He pointed his finger and said, ‘That’s going to be commercial.’ And it was! From the LSD movies to motorcycle movies to horror movies, he just hit it right on. He had a great feel for the times and the audience and what they wanted to see. Jack absolutely got his start with Roger. And Francis Coppola came out of there. We didn’t have access to the major studios. We couldn’t go in to Paramount or MGM and play around. Those were closed shops to guys like us. But everyone could have access to Roger. He would give you advice, he would help you get financing. Roger was very sympathetic to young filmmakers. And talent had a way of finding him very often. You had to find a way into this maze, and that was the way.”

Frame grabs from The Trip (1967). Peter Fonda, Bruce Dern, Susan Strasberg, and Dennis Hopper grapple with the infinite (not to mention citrus, spiderwomen, fog-shrouded dream chambers, and love beads) in Corman’s psychedelic freak-out about a “Lovely Sort of Death.”

BRUCE DERN: “When we first started, Dennis Hopper—shit, he was big stuff to us. He did two movies with Jimmy Dean. I mean, my God, Jimmy Dean! Dennis was iconic. He pushed the envelope, but he pushed it too far and in too many directions. His time ran out before he was finished. And that’s a shame. Roger wasn’t as enamored of Jack as an actor he should have been. He liked him as a writer and all-around force; he just didn’t see him as a movie star. And he loved Peter because Peter was a Fonda. Roger always knew what he wanted as a director. I remember asking him while we were doing The Trip, ‘How many of these movies have you actually done?’ This was 1967. He said, ‘Well, this is my hundredth.’ I couldn’t believe it! I mean, the guy had made a hundred movies! And what was interesting about him—well, there’s a lot of interesting things about him—but first of all, this guy that was making biker and acid movies had played on the golf team at Stanford. Secondly, his family were members of the Los Angeles Country Club. I thought, You dirty prick! How can you get in there? Gary Cooper can’t get in there, Clark Gable can’t get in there, I mean, Ronald Reagan was never even allowed to belong!”

ALLEN DAVIAU (cinematographer; post-Corman credits include E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, Empire of the Sun, and Bugsy): “Jack Nicholson’s screenplay for The Trip was brilliant. LSD was a hot topic, and Roger knew that it was something people would pay to see. He also knew that he needed to have some psychedelic special effects because it was a movie about acid, but he sure didn’t want to pay for it. We were shooting on the lot at Raleigh Studios. It was my first time on a big-time movie, and we had to produce a whole aura of psychedelic lighting, and we had strobes and water projectors. Peter Fonda came on the set with a lovely lady named Salli Sachse, who was the most perfect beauty of all time. And we proceeded to film them making love in this deluge of psychedelic light. Roger knew what he wanted and how quickly he wanted to get it. There was no messing around. We thought if we could just have a little more time, it could have been better. But it was the first film that I got a screen credit on: ‘Psychedelic special effects by Peter Gardiner, Bob Beck, and Allen Daviau.’ It was denounced by critics and in the press, but of course it would be. I think people got their money’s worth, though.”

Frame grab from The Trip (1967), directed by Roger Corman. Peter Fonda—this is your brain on drugs.

ROGER CORMAN: “AIP changed the ending of The Trip. What happened is the whole picture takes place in one night and at dawn the next morning. We were at a beach house, and in one shot I followed Peter Fonda with a camera getting out of bed, opening the window, and going out on the deck of the beach house and seeing dawn. That was the ending. I wanted to leave it totally open—that he had taken this trip and now this was a new day, a new chapter in his life. Which I thought was a nice ending. But AIP was afraid that we could be accused of advocating LSD, so they put a big crack across the screen indicating that his life had broken and a terrible thing had happened. Peter Fonda and I both protested. We didn’t like it. Afterward, Peter and Dennis Hopper came up with the idea of Easy Rider. But they had never made a picture, so they came to me and said, ‘You be the executive producer, and we will cowrite the script, costar, and Peter will produce and Dennis will direct.’ I said fine. I thought I could easily get the financing from AIP based on the success of The Wild Angels and The Trip.”

BRUCE DERN: “When they were casting Easy Rider, Jack was an afterthought to play the lawyer. Rip Torn was going to play the part, and then that didn’t work out with some ugliness all around. And then I’d heard it was going to be me. Then Roger had some kind of a falling out with Peter and Dennis.”

ROGER CORMAN: “During a meeting with AIP about Easy Rider, one of the executives there said that they want the right to replace Dennis as director if he fell more than one day behind schedule. I could see the look on Peter and Dennis’s faces. After Peter and Dennis left, I stayed and I said, ‘You have really made a bad mistake. Peter and Dennis are really mad.’ I understood why they were worried about Dennis, who was well known for drugs and causing problems on sets, and he’d never directed. But I told them that I was going to be there and how before The Trip, I had dinner with them and explained to Dennis that we had a short schedule and that I was concerned. And Dennis said, ‘I understand, you don’t even need to finish. I will be there every day on time, I will be totally professional.’ And he was. I told AIP that I would do the same thing again because my experience with Dennis had been excellent. I would be there, and I would take care of it. But Bert Schneider and Bob Rafelson heard that Peter and Dennis were mad, and they made them an offer for a little bit more money and didn’t impose any of those sorts of restrictions. And, of course, Easy Rider became the biggest grossing low-budget picture of all time. We all lost out because of this one statement. AIP knew they’d made a mistake. And I was mad. I didn’t know Easy Rider was going to be that big, though. No one did.”

PETER FONDA: “I don’t know that Easy Rider would exist without Roger. I just thought of the idea to make a movie where these two guys were heading east—a little homage to Hermann Hesse’s The Journey to the East, which Dennis had turned me on to. So I started writing a first draft of the script. I started with the ending first, thinking, This will really shake the audience up! I never would have gotten to that moment without that confidence that I’d gotten from Roger. I would watch him shoot. Those stories about Roger using wheel-chairs for dollies, they’re true! I remember asking Roger where my dressing room was, and he said, ‘You see that tree over there?’ Roger was going to be our executive producer on Easy Rider. But AIP said they would take the film away from Dennis if he ran over. And I said, ‘I can’t do that to Dennis.’ This was not their call. And so we decided that we had to take a pass. In the timing of life, we just happened to hook up with Bob Rafelson, who was a friend of Jack Nicholson’s—they were making a movie together called Head with The Monkees. And they asked me what was happening with the motorcycle movie I was working on. And that’s when we met Bert Schneider, and he said, ‘You’re making a motorcycle movie? Is it good? How much do you need for it?’ I wasn’t ready for that question. But I had seen the budget on The Wild Angels, so I said $360,000—like I knew! And so he said, ‘OK, let’s do it.’ He let us shoot it the way we wanted to.”

U.S. poster for Easy Rider (1969), directed by Dennis Hopper. A tense showdown with AIP led Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda to take their counterculture road movie to hipper financiers. As a result, Corman missed out on what would have been the biggest hit of his career.

Lobby card for Easy Rider (1969). After taking the Cannes Film Festival by storm, Jack Nicholson and Peter Fonda (and director Hopper) became the icons of a new generation … and the poster boys for the New Hollywood.

PETER BOGDANOVICH: “Roger called me one day and said, ‘Do you want to make a picture?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ He says, ‘OK, here’s the deal. Boris Karloff owes me two days’ work. What I want you to do is shoot twenty minutes of Karloff in two days. You can shoot twenty minutes of Karloff in two days, I’ve shot whole pictures in two days. Then I want you to take twenty minutes of Karloff footage out of the picture we made called The Terror. It’s not a very good picture, but you can get twenty minutes out of Karloff there. Now you’ve got twenty and twenty, that’s forty minutes of Karloff. Now I want you to go and shoot with some other actors for ten or twelve days and shoot forty minutes with them, and I’ve got a new eighty-minute Karloff picture. Are you interested?’ I said, ‘Yep, yep, yep.’ And then he said, ‘Oh, and by the way, I’ll pay you $6,000, and you can have Polly work on it, too, but I want you to do one little thing for me first. There’s a Russian science-fiction film called Storm Clouds of Venus. AIP looked at it, and it’s got some terrific special effects, but there’s no women in it. It’s about a bunch of actors on planet Venus and there’s no women in it, and AIP says they won’t buy it unless you put some women in it. What I want you to do is go down to the beach, and we’re going to hire Mamie Van Doren, and we’ll get a couple other of those girls, and I want you to figure out a way to put some girls into the picture. It won’t take you long, it’s a week’s work.’ You can’t make this up. So I looked at this Storm Clouds of Venus, which was a piece of shit, and I didn’t think the special effects were that hot either. Oh, and Roger said, ‘By the way, you can’t shoot with sound.’ I said, ‘What do you mean, no sound?’ ‘I don’t want to pay for a sound crew.’ ‘Well, how are they going to communicate?’ He said, ‘That’s up to you.’ So I thought, Well, I guess telepathy. He eventually released it under the title Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women, and it’s terrible. But the great thing about Roger, and what I’ll always appreciate, is he would throw you in the ocean and say ‘Swim.’ And if you swam, you were fine. If you drowned, that was it.”

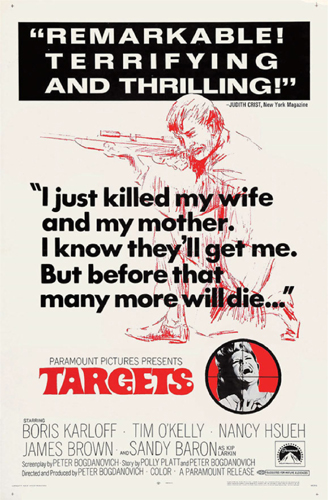

U.S. poster for Targets (1968), directed by Peter Bogdanovich. Perhaps as compensation for getting stomped by Hells Angels on the set of The Wild Angels, Corman gave former Esquire film critic Bogdanovich a shot at directing a film of his own.

FRANK MARSHALL: “I think it was 1968 when Peter Bogdanovich finally called. I thought he had forgotten about me from our meeting at John Ford’s Christmas party before he went off and did The Wild Angels. He said that he and his wife, Polly, had written a script and moved out to L.A. He said, ‘I can’t pay you anything, but I can pay for your gas and food.’ And I said, ‘What do you want me to do?’ And he said, ‘I don’t know, I’ve never made a movie before!’ It was a ball. I thought, You can do this and make a living? Roger was sort of like a godfather who had an office, and he was churning out all of these movies and just trusting people. It’s amazing when I think about how things are run today—nobody would do what he did. He would just take these young filmmakers and say, ‘Here’s $125,000, go bring me a movie. I have Boris Karloff, he owes me a week.’ ”

Frame grab from Targets (1968). Boris Karloff adds a touch of class (and an above-the-title name) to Bogdanovich’s directorial debut—an eerie thriller about a serial sniper that showed the young director’s clever resourcefulness.

PETER BOGDANOVICH: “We tried to figure out what to do with Karloff. I couldn’t imagine making this Victorian horror movie that would match The Terror; I mean, it was just hopeless. And then we remembered that while we’d been in New York the last time, Esquire editor Harold Hayes had said, ‘Why don’t you make a film about that guy in Texas who shot all those people in 1966?’ He went to the tower of the University of Texas in Austin and shot about thirty people. So we thought, What if Karloff played an actor who’s retiring because his kind of horror isn’t horrible anymore? What’s really horrible is this guy in Texas. So, what if we tell a story cross-cut between these two stories? How a kid who goes berserk and kills his family and starts killing people randomly. So that’s what happened on Targets. I showed the screenplay to Roger, and he said, ‘This is one of the best scripts I’ve ever gotten.’ And Karloff liked the part. We got him some extra money for three more days, but he worked from nine until three in the morning. He had emphysema and he had braces on both of his legs, so he couldn’t walk very well, but he had fun.”

FRANK MARSHALL: “Karloff was such a professional. He was at the end of his career and happy to be acting. Peter had incredible respect for him and of course knew all of his movies. I remember when we shot at the drive-in and it was cold and he was walking with a cane; he was pretty old, and he was such a trouper—he was out there in the middle of the night. Peter gave me a small role as the ticket taker at the drive-in. I have a scene with Peter, actually. He drives up and says, ‘Where is the stage?’ And I say, ‘Down there on the left’ or something. I thought the movie was fantastic. I even look at it today, and the storytelling and the shots are fantastic. The film was quite controversial because of the anti-gun lobby and all of the assassinations at the time. We had to run a crawl at the beginning of the movie about gun violence and gun control. It was an amazing thing, and it certainly became a calling card for Peter. It didn’t do a lot of business, but it got the critical acclaim that allowed him to get The Last Picture Show.”

PETER BOGDANOVICH: “We had a screening of Targets at Jennifer Jones’s house, and everybody was there: Peter Fonda, Jim Coburn, Dennis Hopper, Jack Nicholson. And when the picture was over, nobody said a thing to me. Not a word, not a word! They just went on like they hadn’t seen a picture. The only person who came over was Nicholson. He plunked down next to me and says, ‘This is a terrific picture.’ It was very sweet, and it meant the world to me at the time. He didn’t have to do that, but he did.”

MARTIN SCORSESE: “At the tail end of the sixties, I was working as an instructor at NYU. Around that time, some of my students like Jon Davison and Jonathan Kaplan had sort of gotten swept up in the cult of Corman. A lot of the students were walking around with Roger Corman buttons. This was at a time when we were told that American movies were no good. We were told that European films were the only good films. Embracing Corman was embracing something that was a provocation. But it was done with conviction.”

JONATHAN KAPLAN (director; post-Corman credits include The Accused and ER): “I went to the University of Chicago and was planning on majoring in art history, but I got thrown out for protesting the war in Vietnam. So I signed up for NYU film school, because I was at the top of the list for the draft and I wanted to have a student deferment. A friend of mine who was going to NYU said it was easy—all you do is watch movies. The film school was literally just half a floor on Greene Street, and we shared it with the Serbo-Croatian library. We made a student film, which was a little racy. In those days, they called them nudies. It was called These Raging Loins. It wasn’t hard-core; it had some topless stuff, but it was funny. Martin Scorsese was brought in to teach a film appreciation class. He came in and asked us our favorite filmmakers, and we all said Godard and Truffaut and Chabrol, and he said, ‘Well, you need to learn about American films.’ And the first film he showed us was The Searchers. We were all appalled that he was showing us a film with John Wayne, who was for the war. We were like, What the hell? Who is this little Italian guy showing us this right-wing crap?! He’d show the film once, and then you’d take a break, and then he’d show it again and stop and start and he would talk about it. It was fantastic. He showed us North by Northwest, The Bicycle Thief, Panic in the Streets, The Lady from Shanghai. He was pretty young and so enthusiastic, jumping up on the tabletop acting shit out. While I was a student, I was also working at The Fillmore, and I’d get Marty tickets to concerts. Allan Arkush and Jon Davison worked there, too.”

Photo of Martin Scorsese in 1969. The twenty-seven-year-old director had recently completed the low-budget black-and-white New York story Who’s That Knocking at My Door. Corman saw the film and immediately recognized a talented new voice. © Pierre Venant/Corbis

ALLAN ARKUSH (director; post-Corman credits include Crossing Jordan and Heroes): “While we were at NYU, we went on strike. We took over the eighth floor and we had a sit-in, where we watched movies and smoked pot. Marty was there, and I think the projectionist may have even been Billy Crystal. Around two in the morning we ran out of movies. So they called up Jon Davison and said, ‘Jon, we need some more movies.’ And he brought Little Shop of Horrors. We’d been up half the night smoking bad pot. So we were the perfect audience for that movie.”

JONATHAN DEMME (director; post-Corman credits include Something Wild, The Silence of the Lambs, and Philadelphia): “I was living in London in the late sixties, and I was producing TV commercials. I had a background as a film publicist, and I received a phone call from United Artists, which was financing a Roger Corman movie that was going to be shot in Ireland called Von Richthofen and Brown. They were calling to see if I was interested in being the unit publicist on that film. I was, of course! I was a huge Roger Corman fan and an intense cinephile. I’d written some film reviews for tiny local papers, but I had no filmmaking aspirations whatsoever. I loved movies, but I was fine with being a publicist. Roger looked at some of the publicity materials I had written and asked if I thought I could write a screenplay. I said, ‘Umm, yes?’ He said he was starting a new company back in Los Angeles called New World Pictures, and he needed to generate scripts so he could get some movies in production.”