VHS: WHEN THE BIG PICTURES GOT SMALL

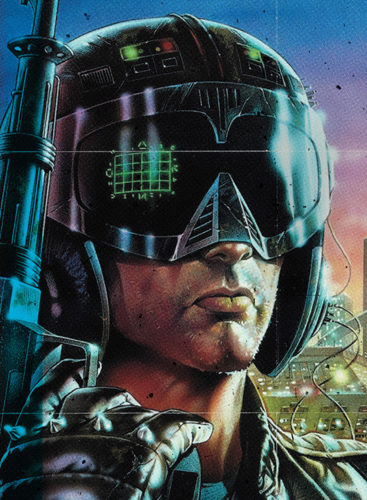

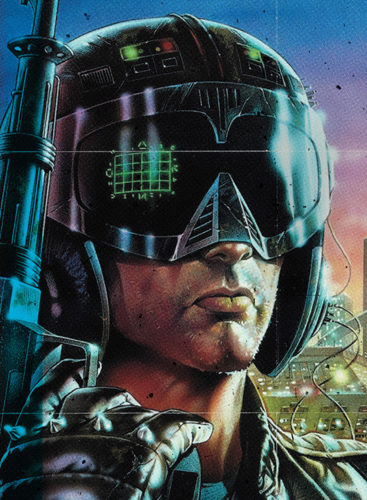

Frame grab from Galaxy of Terror (1981), directed by Bruce D. Clark.

AS THE CURTAIN ROSE ON THE EIGHTIES, New World was more profitable than it had ever been. Roger Corman was still the most successful independent producer the industry had ever seen (Miramax was still a shoestring operation run by the Weinstein brothers in Buffalo). And yet the future, for the first time, seemed uncertain. With the recent acquisition of an old lumberyard in Venice, California, Corman created his own soundstage, where he could quickly produce sci-fi spectacles that he hoped might compete, in some small way, with George Lucas’s epics.

Battle Beyond the Stars was Corman’s most ambitious film to date. Written by future Oscar nominee John Sayles as a sort of Magnificent Seven in space, the 1980 film represented big breaks for several future Hollywood heavyweights. James Horner composed the rollicking score, Gale Anne Hurd was a trusted Corman production executive on the film, and future King of the World James Cameron began the production as the low man on the totem pole in the movie’s prop department and had been promoted to art director by the time it wrapped. Corman still had a knack for spotting talent—and compatible employees: Hurd and Cameron would get married in 1985. When Battle Beyond the Stars was released, six months after The Empire Strikes Back, Corman’s high risk yielded a high reward. The film was the biggest grosser in New World history.

Not surprisingly, Corman was routinely approached with lucrative offers to sell New World. And in 1983, he received an offer too good to refuse. As part of the deal, Corman reportedly agreed to stay on as a consultant for two years continuing to make films for New World, and signed a noncompete clause. After feeling that his films were being iced out by the new New World, Corman went back into business for himself, forming a distribution and production company that would eventually be known as Concorde–New Horizons. Regardless of his company’s name, Corman continued throughout the eighties to be a maverick when it came to hiring women. At a time when positions of power in Hollywood were virtually nonexistent for women, Corman employed them at every level. His wife, Julie, was key in this aspect of the legacy. In the eighties, Corman gave a shot to numerous female directors, including Penelope Spheeris (Suburbia), Amy Holden Jones (The Slumber Party Massacre, Love Letters), Deborah Brock (The Slumber Party Massacre II, Rock ’n’ Roll High School Forever), and Katt Shea (Stripped to Kill). All would go on to make movies for the major studios.

As the decade wore on, the lights began to slowly flicker out at drive-in theaters across the country. The outdoor B-movie venues, which had allowed Corman to launch his career in the fifties, were becoming a thing of the past—another dying piece of Americana. Corman was finding it harder and harder to get his films played theatrically. The movie business was changing once again. Still, Corman saw a way forward before his bigger, slower competitors did. The rise of cable and the advent of the VHS market would become Corman’s savior. Concorde–New Horizons essentially became a pipeline of straight-to-video movies that were shipped off in staggering bulk to hungry mom-and-pop video stores around the globe. The quality of the movies coming out of the Corman factory may not have been the best of his career—there was definitely a lack of new Scorseses and Demmes in his stable—but they didn’t have to be. Video was an undiscerning medium with an audience that was ravenous for anything that they could bring home and watch in their own living rooms. These movies didn’t have to look great. They didn’t even have to have traditional “stars.” All they needed was a sensationally sexy or scary box that made them scream from store shelves. And Corman had always been able to do that better than anyone. In the unlikeliest way imaginable, he not only managed to survive a decade that began ominously, he thrived in it.

U.S. poster for Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), directed by Jimmy Murakami. Looking to capitalize on the success of Star Wars, Corman gambled on his biggest production yet—an effects-heavy sci-fi epic shot on his brand-new soundstage in Venice, California (in actuality, it was a damp, dank former lumberyard). Screenwriter John Sayles conceived the story as “The Magnificent Seven in space.” He wasn’t the only soon-to-be A-lister on the film. James Horner composed the score, and James Cameron was the film’s art director.

JOHN SAYLES: “By 1980, Star Wars had come out and The Empire Strikes Back was about to come out. Roger approached me about writing a screenplay that he described as ‘The Seven Samurai or The Magnificent Seven in space.’ He was calling it Battle Beyond the Stars. Roger liked those kinds of ideas. It was a good way to restage a Western like The Magnificent Seven with $1.99 cardboard sets. And obviously the genre was hot at the time. I think I wrote the script in three or four weeks. The rewrites weren’t so much about character. It was more like ‘It’s expensive to show the ship landing and taking off, so can you get rid of those transition scenes?’ What I remember very strikingly about Battle Beyond the Stars is that it was being cofinanced by a big studio, Orion. They were going to put up half the money—Roger was putting up a million and a half, and Orion was putting up a million and a half for foreign distribution rights. We rode over to Mike Medavoy’s office at Orion in Frances Doel’s little Volkswagen with Roger crammed into the backseat. At Orion, there was Mike with his cigar and a secretary who looked like Miss Universe. You could tell Roger was kind of having fun being there and looking around and seeing all the big-studio stuff he didn’t need to be successful. They shot Battle Beyond the Stars in an old lumberyard Roger bought in Venice to use as a soundstage. He was building his own studio lot. And you’ll notice that there’s not a lot of panning in that movie, because if you pan too far, you could see the lumber still stacked up. Roger had hired away some of the young kids who had worked on Star Wars. And that was also one of the first jobs that James Horner, the famous composer, did—back when he was ‘Jamie’ Horner. Roger recycled that score and some of those model shots in a couple of later movies. I think he was just trying to say, Why let it go to waste when it was good work? My only disappointment with the film was there was one character who I had written—Cayman, I think his name is—who was supposed to be a walking, talking lizard. And they just got a big guy with tattoos, because I think designing a full-body costume would have been too expensive. It’s definitely a cheesy look, but some of what I wrote into it, knowing that it was not going to be able to look like Star Wars, was that this was a trashy universe. One of the characters is a trucker, not some rocket scientist. He’s just driving this space rig. I tried to anticipate the low-budget look that it was gonna have. I thought they actually did a nice, imaginative job, like having the mother ship have breasts. I think that was James Cameron’s idea.”

Stills and foreign lobby card from Battle Beyond the Stars (1980). Clockwise from top left: John Saxon stars as the film’s nefarious Darth Vader stand-in, Sador. Morgan Woodward, underneath green reptilian latex as Cayman, says words to the effect of “These are not the droids you’re looking for…” Former Waltons star Richard Thomas suits up as an innocent farm boy who becomes a galactic hero, even without “The Force.”

JAMES CAMERON (director; post-Corman credits include The Terminator, Aliens, and Titanic): “I had been sort of preparing myself for a career in visual effects by learning about mold-making and sculpting and matte camera and optical printing on little film projects in Orange County with some other eager wannabes. And we got a lead that there was a film being made up in Venice with visual effects for Roger Corman. I knew who Roger Corman was, and I knew the films he had made. So I trooped down there, and they had an opening for a modeler. I started off as the lowest man on the totem pole in the model shop. I was just happy to be on a film—I didn’t care that it was a pretty rinky-dink production. This was at the lumberyard, which was basically just an empty building with a floor that was flooded. Roger came through one day, and he kind of threw down a challenge to everyone in the model shop. Actually, he was kind of pissed off. We’re so many weeks away from shooting, and no one had even designed the main character ship for Battle Beyond the Stars. The main space ship had a female computer. It was kind of a HAL 9000, but female. He said, ‘I want a design in the next two days.’ So it sort of became a sort of design contest, and I thought, OK, it’s Roger Corman. He does girls-in-bamboo-cages movies. What is he selling? He sells tits! So I designed a kind of Amazon warrior spaceship—basically a spaceship with tits. It was a cool design. Roger came through and he looked at all of the designs, and he stopped at mine and he went: ‘This is it, this is exactly what I want.’ He said, ‘What is this?’ And I said, ‘This is a spaceship with tits.’ And he says, ‘Yes, that’s exactly what it is. You build it.’ So suddenly, I was the guy in the model shop that everyone hated.”

Frame grab from Battle Beyond the Stars (1980). Art director James Cameron described his early sketches of the film’s vessel to Corman as a “spaceship with tits.” Corman got it immediately.

Battle Beyond the Stars 1980

By the end of the seventies, it had become clear that Star Wars had changed the movie business forever. But rather than throw up his hands and cry uncle, Roger Corman was determined to follow the age-old adage about the rising tide lifting all boats. He would make a (relatively) expensive space blockbuster of his own. He wasn’t the only producer with this idea. Disney quickly green-lit The Black Hole, Paramount resurrected the crew of the Enterprise for Star Trek: The Motion Picture, and on TV, Buck Rogers and Battlestar Galactica brought galaxies far, far away into America’s living rooms. For his part, Corman decided that he would saddle up with big-studio Orion (if you can’t beat ’em…) for Battle Beyond the Stars. Initially conceived as a sort of Magnificent Seven in space. Corman tapped Piranha writer John Sayles to pen the script. And what he got was one of the most self-aware, genre-tweaking sci-fi films in a decade of straight-faced sci-fi films.

Shot in Corman’s recently acquired soundstage in Venice, California—it was a converted lumber warehouse prone to flooding—the $2 million Battle Beyond the Stars would become a proving ground of rising Hollywood heavyweights. In addition to Sayles behind the Underwood, the film featured a rousing score by future Oscar-winning composer James Horner, an assistant producer credit for future Tinseltown heavyweight Gale Anne Hurd, and art direction by a twenty-five-year-old wunderkind named James Cameron. The film was Cameron’s first for Corman, and his boundless creativity quickly vaulted him up the pecking order from low man in the model shop to the main architect of the film’s brave new look. Perhaps his biggest contribution was the design of the main spaceship in the movie, Nell—a sleek, octopus-looking female vessel with giant breasts on its prow. Or, as Cameron pitched it to his boss, “It’s a spaceship with tits.” The Millennium Falcon, it wasn’t.

Foreign lobby card for Battle Beyond the Stars (1980). Darlanne Fluegel stands up to pressure. Where’s John-Boy Walton when you need him?

Animator-turned-feature director Jimmy Murakami’s sci-fi epic kicks off with an evil Vaderesque villain (John Saxon), who threatens the peaceful planet of a naïve young pilot named Shad (John Boy from The Waltons, Richard Thomas). To save his home, he assembles a posse of colorful mercenaries, including George Peppard’s Cowboy (whose utility belt dispenses scotch and soda), Sybil Danning’s buxom Valkyrie warrior Saint-Exmin (her barely concealed cleavage was so in-your-face that NBC had to fog out her chest when it later aired the film on TV), and Robert Vaughn as the infamous outlaw Gelt (essentially reprising his role from The Magnificent Seven).

The film’s “ping-ping” sound effects, intergalactic aerial dogfights, and Styrofoam sets made out of McDonald’s Big Mac containers may have seemed primitive compared to what George Lucas was doing at the time. But its $7.5 million box-office haul in the summer of 1980 made it the biggest hit in the history of New World Pictures.

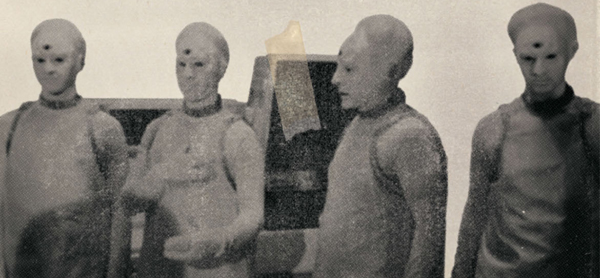

Still from Battle Beyond the Stars (1980). Nestor, Kabuki-faced aliens with a collective hive mind, sign up to join the cause.

GALE ANNE HURD (producer; post-Corman credits include The Terminator, Aliens, and The Walking Dead): “The first movie Roger sent me to the set of was Humanoids from the Deep. I put super-slime cellulose on the monsters right there with Rob Bottin. After that, Roger said, ‘I need someone to go down and check to see how preproduction is coming along on Battle Beyond the Stars. Can you go down to the lumberyard and see how the sets are coming along?’ I walked into the model shop, and this very tall, blond gentleman came up to me and said, ‘What can I do for you?’ And I said, ‘Can I tour the model department? I work for Roger.’ So he showed me around, and he had designed the spaceship exteriors and was building them, and they looked fantastic! I assumed he was the head of the model shop, but he wasn’t. He was Jim Cameron. I realized not one set was under construction. So I went back and I said, ‘Roger, I think we have to build twenty-five sets in a few weeks and not one of them has been designed, much less started construction.’ And he said, ‘What do you recommend?’ I said, ‘I know this sounds outrageous, but there’s a terrific artist who’s designed and built the spaceship. He knows what the exteriors look like. Would it make sense for him to design the interiors as well?’ And that’s how Jim moved over to run the art department on Battle Beyond the Stars. Under Roger Corman you could go from being a model builder to art director in twenty-four hours.”

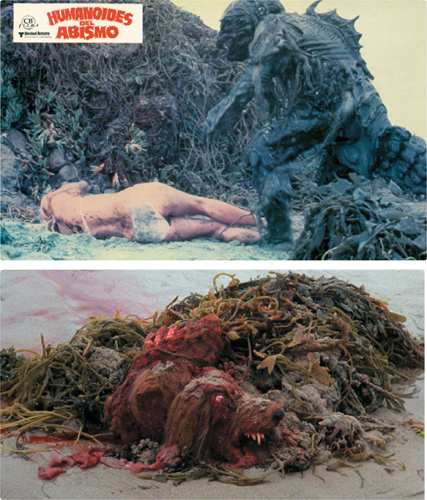

Lobby card and still from Humanoids from the Deep (1980), directed by Barbara Peeters. Rob Bottin, who would later become the gross-out makeup effects guru behind The Thing, and future producing superpower Gale Anne Hurd got early breaks on Corman’s fright flick about man-eating (but mostly woman-eating) sea mutants.

JAMES CAMERON: “So that’s how that happened? That’s probably true. Gale used to come in and hang around. She had her headlights on. She was an up-and-coming producer. She was interested in all of the effects processes, and we just kind of naturally gravitated to each other. At that point, it wasn’t even anything romantic. We were just so focused on our careers, I don’t think that a romantic relationship even occurred to us at that point. The problem was that the guy who I was replacing, his job was to design something like twenty-five sets. Well, he’d only made two, and they were going to start shooting in four days. It was a complete nightmare. No one knew what the hell they were doing, and I just took charge. Roger fired me two or three times. The first couple of times I got fired, they would just rehire me behind his back because nobody else could get the sets built. One day, Roger comes in and we were working on some set—I think it was a robot workshop—and he says, ‘This is just a shitty little set, why isn’t it done? Look at this, the paint is still wet!’ The mistake I had made was my crew was still there working on it. And I quickly realized that it didn’t really matter to Roger how good the set looked, it only mattered that it was done. So I arranged a system where I set up a spotter to look out for his white Lotus coming down the street, and we used walkie-talkies and I had a code, like ‘The Eagle has landed!’ And I drilled everybody and said, ‘When I blow this horn three times, no matter what you are doing, drop your tools and walk outside and get a cup of coffee. When you hear three blasts, it’s down tools, walk out now.’ So at six forty-five in the morning, the white Lotus is coming down Main Street in Venice, and somebody gets on the walkie-talkie and says, ‘The Eagle has landed!’ I grab the horn and blow it three times, and everyone walks out to get an egg sandwich, and Roger pulls in and walks around and there’s no one working on the set, and he goes, ‘Very good.’ And walks out. And that was it. I realized how you played that game.”

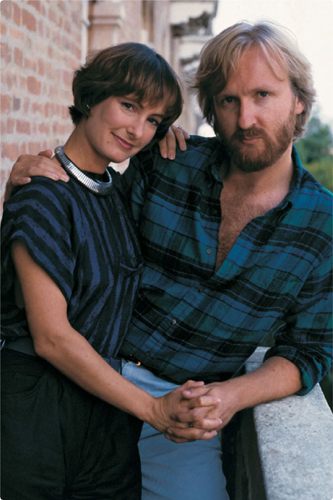

Gale Anne Hurd and James Cameron (pictured here) first met at Corman’s lumberyard soundstage during the making of Battle Beyond the Stars. Soon, they would become partners on screen (The Terminator, Aliens) and off (they were married from 1985 to 1989).

SYBIL DANNING (actress; post-Corman credits include Chained Heat, Reform School Girls, and Grindhouse): “I think Battle Beyond the Stars was one of the first movies they made in Roger’s lumberyard studio, and it looked like it was just pulled up from the deep. Mushrooms were growing on the walls. But I didn’t care, because it was my first big movie in America. I remember there were a lot of fittings for my Valkyrie costume. They had to build a cast for my Styrofoam breast piece, and we always had problems with that when we were shooting. I guess my nipples would keep poking out a little. And we’d have to stop. After the third time, Roger said, ‘Glue her in!’ It was a pretty risqué outfit. When the movie came out on NBC, they actually had to fog out my entire chest.”

Production still of Sybil Danning in Battle Beyond the Stars (1980). The amply endowed Austrian actress got some of the sci-fi film’s most memorable lines as the Valkyrie, St. Exmin. Her form-fitting costume was so risqué that her chest was fogged out when the film eventually aired on TV.

BILL PAXTON: “In the late seventies, I moved to New York for a few years and studied drama at NYU. When I came back out to L.A., I was doing odd jobs and things, and trying to get some acting work. I needed a job. I was living about a dozen blocks north of the lumberyard studio Roger bought in Venice. He had started doing these low-budget science fiction movies there. They had a couple of little stages. And my friend said, ‘Hey, I’m working out there for this young art director named Jim Cameron, and my God, he’s really something. I think I can get you on the night crew. Come down and I’ll introduce you to Jim.’ So I got down there at seven o’clock, and Jim says, ‘Phil tells me you’ve worked in the art department.’ I go, ‘Yeah.’ ‘And you’ve worked for Roger Corman?’ ‘Yeah.’ And he said, ‘Well, can you start right now?’ And I go, ‘You mean, right now?’ And he goes, ‘Yeah. Go paint that wall over there.’ And that’s how I met Jim Cameron.”

U.S. poster and frame grab from Galaxy of Terror (1981), directed by Bruce D. Clark. Corman’s splatter-packed stab at Alien featured the special-effects handiwork of James Cameron and his young apprentice, Bill Paxton. Yes, that Bill Paxton.

JAMES CAMERON: “Bill came in, and we just called him ‘Wild Bill’ because he was big in gesture and speech, and he was obviously a natural performer. I knew he was trying to act as well, but I didn’t care about that—at least until a couple of years later and I was doing The Terminator, and I cast him in a small part as one of the punks who’s killed in the beginning of the film. When he first came in, I was right in the middle of building a set, and I said, ‘You, can you paint?’ And he said, ‘Yeah, baby!’ And I said, ‘Get over here and paint this wall.’ ”

BILL PAXTON: “Well, I just remember the conversation was very succinct. I was pretty gung-ho. He coined a term called ‘kluging.’ It’s taking disparate things and making something out of it. So we were taking everything from, you know, photo tubes to industrial dishwashing racks to Winnebago molds and just putting them all together and creating these spaceship interiors. We’d spray them all down with paint, and then we’d trick them all out with set dressing. He was amazing.”

JAMES CAMERON: “I was trying to emulate this look of Silent Running. Doug Trumbull had a lot of vacu-formed wall modules that he created on that film. I didn’t have access to that kind of equipment; I had to whip something up. So what I did was I got a bunch of these Styrofoam trays—McDonald’s breakfast trays of all different sizes and put them into configurations and hot-glued them onto the walls in patterns. I just did it the super-cheapo way. We bought them in bulk. I had one rule, which was never unplug your glue gun. And I used to scream at people about it because they took twenty minutes to heat up, and if you just left it on all night, then you could just quickly glue things together. I developed this whole method for cutting foam-core and scoring it on the backside and bending it so it looked like formed metal and spraying it with automotive lacquer and metallic paint. It looked pretty good.”

BILL PAXTON: “While we were making Galaxy of Terror, I had sold a little short I had made to Saturday Night Live, and Jim was very taken by that. And suddenly he looked at me as not just a guy painting sets but actually as a guy who had a similar ambition to his—to be a filmmaker. About halfway through the thing, I remember one night, Jim and I were kind of working side-by-side, and he started telling me about this screenplay he was writing. And I’ll never forget, he said, ‘It’s about a cyborg from the future that comes back to the present to kill the woman who’s going to give birth to a son who, in the future, is going to lead a revolution against the machines.’ And I was like, ‘Far out, what are you going to call it?’ He said, ‘I’m going to call it The Terminator.’ ”

JAMES CAMERON: “I hit Roger up in the hall one day and said, ‘We’re falling behind on Galaxy of Terror and you’re not getting coverage, so why don’t you let me direct second unit?’ He said OK. And I kind of also became an alternate first-unit director because they fell so far behind that I had to do actual scenes with the actors. That was my first experience directing. I sort of thought maybe I should think about directing because I keep building these cool sets and these guys keep shooting them like idiots. I knew how it should be done, and I was watching these boneheads, thinking I can do better than this! So yeah, I was looking for an opportunity to direct. I wrote a couple of scenes where this guy cuts his arm off with a crystal and the crystal attacks him. But I didn’t write the infamous scene with the giant maggot raping that woman. Roger always had to have a rape scene in all of his films—it came from his biker films and women-in-prison films. I didn’t approve of it at all, but I wasn’t judgmental about it. Anyway, the whole maggot rape scene starts with this severed arm with these maggots on it, and one of them grows. I had to do a POV shot of the arm lying on the floor with maggots on it. So they bring me the arm, and they bring me the worms. I look in this container that they got from this pet store, and they’re mealworms that you use to feed lizards. And they didn’t do anything! So I sprinkled the worms on the arm and I stared at them and thought, Well, this doesn’t work. What are we going to do? So I said, ‘All right, get me some methylcellulose.’ I poured that over the arm, I poured the worms in the methylcellulose, I took a piece of zip cord and split it and stripped the ends, and I ran the zip cord around behind the set and I buried it under the dirt, and I put the leads in the methylcellulose, and I had a guy behind the set who was going to plug it into a junction box. I set up the camera, and I pointed it down at the arm. And meanwhile, unbeknownst to me, two guys have wandered up behind me, one of them I know who’s a sleazeball producer named Jeff Schechtman, and the other one is another sleazeball producer named Ovidio Assonitis who was going to produce Piranha II. So these guys are watching me, and what they see is me pointing a camera at an arm with a bunch of inert worms on it, and then I say, ‘Action,’ which is the cue for the guy to plug the zip cord in, and all the worms come to life! They’re writhing around trying to get out of this electrified methylcellulose, and then I’m shooting it. And then I say, ‘Cut,’ and the guy unplugs the zip cord, but you don’t see him because he’s behind the set wall. So what these two producers are seeing is that I say, ‘Action,’ and all of these worms start squirming around and I say, ‘Cut,’ and they stop. They can’t figure it out. And what I hear back later is they go off and talk and say, ‘If he’s that good with worms, I wonder what he can do with actors!’ And that’s how I got to direct Piranha II: The Spawning. Here I was, I’d gone through the Corman system like crap through a goose, and all of a sudden I was directing a movie and everyone hated me again.”

GALE ANNE HURD: “When Jim and I were initially going to make The Terminator in 1983, Arnold Schwarzenegger became unavailable because Dino De Laurentiis went forward with Conan the Destroyer. So at that point Roger offered me the job of going down to Argentina and overseeing the movies he was making down there. But my heart was in The Terminator. We talked to Roger about financing it. We needed $6.4 million. And he said, ‘Well, can you do it for under two?’ He knew it wasn’t something that could be done for his budget. But a Corman connection did get the movie made, because Barbara Boyle, who had worked for Roger, went over to Orion, as had Frances Doel, and they read the script and convinced Orion to finance it.”

Frame grab [bottom] from Galaxy of Terror (1981). James Cameron was so creative in making inert maggots squirm on a severed arm in Galaxy of Terror that he was hired to direct (and then was fired from) 1981’s Piranha II: The Spawning [top].

ALLAN ARKUSH: “In retrospect, I think when Roger bought the lumberyard, that was a bad thing for the quality of the movies. He started shooting everything on the stage so he wouldn’t have to have permits and police and pay for insurance everywhere, and save money in production that way. But it limited the movies to only what he could make indoors. And so the genres all of a sudden became limited. Then he did the slasher movies because those were hot. He did so many of them, but they’re not a particularly creative genre. But he could sell them overseas. The problem is, it’s a little bit like strip-mining. There’s nothing left of the mountain when you’re done.”

FRED OLEN RAY (writer, director, producer; credits include Scalps, Hollywood Chainsaw Hookers, and Evil Toons): “I grew up on the Edgar Allan Poe films. I had all these model kits and magazines like Famous Monsters, which is where I saw that other kids were making 8mm movies and stuff. So I got hold of a home movie camera and started making little films in Florida. I was interested in makeup more than directing. I wanted to make the monsters. I worked on a movie called Shock Waves and a while later drove out to L.A. and worked on some small films like Biohazard and The Tomb. Some friends of mine, like Bob Skotak, had been working over at Corman’s lumberyard. They showed me all these spaceship sets. And I wanted to make this movie called Star Slammer, so I rented Roger’s studio for a couple of days using some of his old Space Raiders sets. I shot a bunch of girls in sweatpants and stuff running around with Aldo Ray. I also negotiated with Roger to use some stock footage from Battle Beyond the Stars of spaceships and stuff. They wanted $4,000 a minute. We also grabbed some Galaxy of Terror costumes.”

JIM WYNORSKI (director; credits include Chopping Mall and Dinocroc vs. Supergator): “I was originally hired to do advertising and publicity for Roger. The first campaign I did was for the Don Knotts–Tim Conway movie The Private Eyes. It was one of their biggest hits. So I thought, Hey, I’m doing good here! Then he had a film he was going to distribute called Island of the Fishmen. He told me to make a poster that was like Humanoids from the Deep. I said, ‘Roger, this has nothing to do with humanoids! People are going to be upset!’ He said, ‘Or it will get them in the theater.’ They spent a lot of money on it, and they didn’t make a dime. So Roger said, ‘Here’s some more money, go do a new campaign.’ I was friends with Rob Bottin, you know, before he did The Thing. And there were still some sets up from Galaxy of Terror. I went over there on a Sunday and shot a new TV spot for Screamers, which is what Roger was now calling Island of the Fishmen. I told Rob that I wanted to see a man turned inside out. So he devised this thing with goo that looked awful. And we shot this on these big sci-fi sets with a girl in a lab coat that gets ripped off, and she’s wearing a bikini, and this inside-out man chases her around. I put together a thirty-second spot and a ten-second spot, which did not include one frame of footage from the movie, just my stuff. ‘They’re men turned inside out, and they’re still alive.’ That was the catch line, and it was all this great comic-book stuff shown on big sci-fi sets, with hot chicks with big tits. Roger didn’t look at it, and they sent the spots to Atlanta. I’ve been on the job approximately two months. And Saturday morning at seven A.M. I get a phone call from Roger. I was like, gulp. He said, ‘What did you put in those spots for Screamers?’ I told him. And after I got through there was a silent moment, and I was waiting for the Donald Trump ‘You’re fired.’ But instead, he said, ‘Is it in the movie?’ I said, ‘No, it is not.’ And he finally says, ‘Well, we’re going to have to put it in the movie. They rioted at the drive-ins last night. They tore speakers out, they threw them everywhere, and almost lynched the manager at one theater because they didn’t get a man turned inside out.’ But he said to me, ‘Jim, you turned the picture around. We got great grosses.’ That was my first directing gig anywhere. Look, Roger’s goal in making movies was putting people in seats. That’s what they did at AIP in the good old days. I mean, look at Invasion of the Saucer Men. The poster for Invasion of the Saucer Men promises the world! You look at the poster, it’s flying saucers destroying cities, and it’s amazing. But what you get is a black-and-white little cheapie.”

U.S. posters for Island of the Fishmen (1979) and Screamers (1979), directed by Sergio Martino. Corman secured the rights to distribute a ho-hum slice of Italian schlock whose title translated as Island of the Fishmen. Sensing he needed to spice it up a bit for U.S. audiences, he changed the title to Screamers and tapped Jim Wynorski to shoot a new, gorier trailer. Wynorski succeeded. The only problem was that his sensational scenes weren’t actually in the film.

Alternate poster for Screamers (1979). Wynorski’s man turned inside out went from rookie mistake to the film’s central selling point.

AMY HOLDEN JONES: “I had edited for a while, and I wanted to try and direct. I went to Frances Doel, when she was still there, and asked what I could do to get a chance to direct for Roger. She gave me a bunch of scripts, and one was called Don’t Open the Door. I read the first eight pages, and there was a dialogue scene, a suspense scene, and a violent action scene. And I thought, OK, that covers it, those are the three things he needs to see that I can do. My husband, Michael Chapman, is a cinematographer and he got some short ends of film for me, and over the weekend I took one of the cameras home and a couple of lights. I got a bunch of actors through ads in the trades, and we used our house as a location. I showed it to Frances, and she called Roger: ‘Look, Amy’s here, and she’s got eight minutes on 35 mm of a script you own.’ He sat me down and said, ‘How much did this cost?’ I said about $1,000. And he said, ‘You have a future in the business.’ And then he said, ‘How much would it take for you to finish this film?’ I hadn’t even read the whole script, so I said, ‘$200,000?’ And he said, ‘OK, we’re in business.’ I was supposed to go off and edit E.T., but this was a chance to direct. The script was terrible. It was about a slumber party and a driller killer, but it had no comedy at all. It just had a central theme about losing your virginity, so I had to totally rewrite it. I had never seen the Halloween movies or Friday the 13th. And I had to make the really terrible call, which was to Steven Spielberg, and say, ‘Look, I have the chance to direct.’ E.T. was a movie that someday my kids could see and that I would always be proud of. But Slumber Party Massacre was gonna be mine. Roger gave me some advice before I went off and directed it. He said, ‘Always put depth in the composition, and make sure you sit down,’ meaning don’t get tired. He also told me to put a classy fake name on the front cover of the script to help get approvals for locations. So I did; I called it Sleepless Nights. The original T-shirts for the film are a big drill, and it says “SLEEPLESS NIGHTS” on them. We previewed Slumber Party Massacre at this place on Hollywood Boulevard where your shoes stuck to the floor, and the rowdy audience was yelling, ‘Kill him! Kill him!’ I was pretty shaken, actually. And at some point I walked out to the lobby, and Roger was there. I went over and I said, ‘Gosh, Roger, what have we done?’ And he said, ‘Are you kidding? That’s the best preview in New World history!’”

U.S. poster for The Slumber Party Massacre (1982), directed by Amy Holden Jones. Corman embraced the early 1980s slasher craze with the phallic Driller Killer.

Stills from The Slumber Party Massacre (1982). The Driller Killer takes aim. High school hotties don’t have a care in the world. But they won’t be laughing for long.

The Slumber Party Massacre 1982

Of all the slasher-movie franchises that were spawned in the body-count-happy decade of the 1980s, The Slumber Party Massacre is the only one to have been entirely written and directed by women. A strange claim to fame, perhaps, but an interesting one considering how ugly and sexist so many of these films were. Not that you would have ever guessed this fact from looking at the New World poster for 1982’s inaugural chapter, where four high school coeds clad in negligees cower from a psycho with a giant phallic power drill hanging between his legs. It’s about as subtle as a jackhammer to the skull.

After Halloween and Friday the 13th terrified teenage moviegoers looking for suburban splatter and late-night catharsis, Roger Corman jumped into the slasher-film fray with one of the more clever and underrated offerings in the genre—a cheekily Freudian campfire tale about a group of high school girls whose home-alone sleepover party is crashed by escaped homicidal lunatic (Michael Villella) whose weapon of choice is an impressively large power drill. Based on a script by feminist author Rita Mae Brown (Rubyfruit Jungle), The Slumber Party Massacre really belongs to New World editor-turned-director Amy Holden Jones. After all, Corman had shelved Brown’s screenplay, and it gathered a thick coat of dust before Jones rescued and reconceived it.

Like so many of its kill-crazy contemporaries, The Slumber Party Massacre is filled with a cast of no-name actors who look as though they graduated from high school a long time ago. And despite the film’s mostly empowering female themes, these actresses seem to have no reservations about stripping down for a gratuitous locker-room shower scene. The cast members worth noting, because they survive the slaughter long enough to make it to the final reel, are popular alpha girl Trish (Michelle Michaels), her loner neighbor Valerie (Robin Stille), and Valerie’s bratty little sister Courtney (Jennifer Meyers), who will become the key connective tissue to Deborah Brock’s loony 1987 sequel, Slumber Party Massacre II.

What makes the film more than just another blood-soaked Reagan-era video nasty is its sly sense of humor and white-knuckle fake-outs. Nearly fifteen years before Wes Craven’s Scream, here is a movie that’s already nodding and winking at the conventions of the genre. Not only does it have more red herrings than a fishmonger (Could the killer be Trish’s pervy, Peeping Tom neighbor? And what about her female gym teacher who seems to take a bit too much interest in her students?), Jones also gives us a stalker who, unlike Michael Myers or Jason Voorhees, isn’t some iconic masked bogeyman. He’s just a middle-aged shnook in a denim jacket. In fact, he’s so vanilla, you’d have a hard time describing him to a police sketch artist. Jones never allows her film to take itself too seriously. After a pizza delivery man shows up with his eyes drilled out of their sockets, Jackie (Andree Honore) gets over her hysteria long enough to eat a slice. Perhaps the best gag, though, comes in the white-knuckle finale, when our heroine swings a machete and castrates the killer’s drill. His reaction is stunned disbelief, unsure what to do now that his tool has been rendered impotent. The distraction costs him. He’s stabbed and collapses into the shimmering turquoise backyard swimming pool. The ultimate Southern California demise.

Frame grabs from The Slumber Party Massacre (1982). A high school sleepover goes very, very wrong when a group of popular girls lines up for the body count. In the bloody wake of 1978’s Halloween and 1980’s Friday the 13th, killing became Hollywood’s business … and business was good.

PENELOPE SPHEERIS (director; post-Corman credits include Wayne’s World): “When I made Suburbia in 1983, it was actually my second brush with Roger. The first was in 1968 when I was cast in a movie he was doing called The Naked Angels. I played Shirley, Animal’s friend. It was a biker movie. We shot it out in the desert. My goal has always been just to make a living. And at that point, I was like twenty years old and it was a gig. Roger had legendary status even back then. He did well with The Wild Angels, and Roger always knew how to keep spinning a successful formula. When I was trying to put Suburbia together, I found a guy in the Midwest—a furniture mogul, actually—who had $250,000 he was looking to put into a movie. And he said if I could match it, he’d invest in the movie. So Roger came on as a producer. He didn’t remember me from The Naked Angels, all he cared about was that I had a quarter of a million dollars sitting there. He’s a businessman. I walked out of his office thinking, I can’t believe I’m going to get this movie made! I had done the documentary The Decline of Western Civilization, but this was my first movie with a script, and I was scared. I didn’t know how to do it. Roger sat me down and talked me through it and gave me these notes that I still have. I never really had a father, but I felt like Roger was a father figure. Plus, he got a good deal out of us. We all wanted to break into the business, and we were willing to pay him! Or work for free! And he took us up on that! We shot Suburbia for $500,000. I was never privy to the books and never found out what he made on the film, but I don’t think he complained. I didn’t care about my end. There were so few ways to get movies made back then. You couldn’t just pick up a digital camera in 1983.”

U.S. poster and frame grabs from Suburbia (1983), directed by Penelope Spheeris. Spheeris cut her teeth on the 1981 punk-rock documentary The Decline of Western Civilization. Two years later, she turned those taboo teens (and sometimes preteens) into the subjects of her provocative, Corman-produced feature debut. The kids were not alright.

Frame grab and U.S. poster from Love Letters (1983), directed by Amy Holden Jones. Hot off the success of Halloween, Jamie Lee Curtis—the daughter of Janet Leigh—was a second-generation Hollywood scream queen. Corman and Jones gave her a chance to stretch beyond horror films. Even if that meant a required nude bathtub scene.

AMY HOLDEN JONES: “When my husband and I were first together—we met on Taxi Driver—I moved out to Los Angeles, and we wrote love letters for a year to each other. I happened to be cleaning up some things years later, and I found them. So I wrote a screenplay called Love Letters, with the hook being that it would have sex in it. And I took it to Roger, who said he was more concerned about nudity than he was about sex. He wanted nudity in it. He liked nudity. And so he picked out some scenes—like the scenes where the female lead is reading love letters—and said, ‘Well, put her in the tub.’ We got Jamie Lee Curtis to do it for $25,000 at a time when she was making $1 million for the Halloween movies. Roger actually loved it. It was a different reaction from Slumber Party Massacre, where I think he saw dollar signs. He was proud of Love Letters. We went out and did festivals with it. But it certainly never got the following of Slumber Party Massacre.”

PENELOPE SPHEERIS: “After Suburbia, Roger walked me through the studio there in Venice, and there was this god-awful-looking spaceship. And he goes, ‘We just shot a movie with this thing, and I want you to think and tell me if you can come up with some other movie using this spaceship.’ And I’m like, ‘Dude, I just did a movie about social rejects and you want me to switch over to sci-fi?’ It was this hokey, papier-mâché purple thing. It was hilarious.”

JOHN SAYLES: “Roger hired more female directors than anybody else. It wasn’t because he was a dyed-in-the-wool feminist. It was just if they had talent and they were cheap, let’s try ’em!”

RON HOWARD: “One of the striking contrasts you noticed when you went to Roger’s company was that there were so many more women in positions of real authority than you ever saw at a network or a studio. And that’s because Roger just thought that these are smart people who were being blocked at the entry level. And he was kind of happy to exploit that. That’s what he would say. But of course I think he knew what he was doing socially, and it was very significant.”

PENELOPE SPHEERIS: “The film industry is like a fort with all of these guys—and they are guys—holding guns saying, ‘You can’t come in!’ But Roger opened the door to that fort for us. It was self-serving to a degree, because he didn’t really pay us, but he always instinctively knew the right people to open the door to.”

JULIE CORMAN: “Penelope Spheeris, now there is a woman who knows her own mind! I think Roger was very color-blind about women. And partially it worked to his advantage, because generally you get them for less money and they were harder working than a guy who would come in and want more money and may not stick around as long. One of the things that’s very attractive about Roger is how much of a start he did give to women. Word just seemed to spread that this was a place where women could start in the business, and there have been a lot of them to come through here. Barbara Peeters did a film for me called Summer School Teachers. Amy Holden Jones did Slumber Party Massacre and Love Letters and went on to write Mystic Pizza and Indecent Proposal. Debbie Brock directed Rock ’n’ Roll High School Forever and Slumber Party Massacre II and went on to do the Honey, I Blew up the Kid, Katt Shea, who was a woman who had no problem with exploitation films, did Stripped to Kill. And then there was Gale Anne Hurd, who was just a cut above all of us, frankly.”

GALE ANNE HURD: “I interviewed to be Roger’s executive assistant in 1978. I was very proud that I could take dictation. I knew shorthand. I thought he would care how fast I could type. But that wasn’t Roger. I guarantee you, at the time, he was the only person in Hollywood who would ask a woman coming in for a job as an executive assistant, ‘Ultimately, what kind of career path do you want to take?’ I didn’t think there was a career path! It hadn’t occurred to me. And I said, ‘Roger, I’d like to follow in your footsteps and be a producer.’ And he said, ‘Tremendous!’ Roger actually felt that women were better employees than men. We worked harder, for less money, and we were held to a higher standard. Not by him, but by the industry. And he realized that we were the best deal going and we were incredibly loyal, so he looked at it as a win-win proposition.”

U.S. poster for Sorceress (1982), directed by Jack Hill (as Brian Stuart). Hill (of 1970s Philippine women-in-prison fame) returned to the Corman fold to partner up with New World merry prankster Jim Wynorski for this sword-and-sorcery cable classic featuring the thespian talents of Playboy Playmate twins Leigh and Lynette Harris.

FRANCES DOEL: “Some people have said—I don’t agree with it—that Roger hired so many women because they would work cheaper. I think he just liked working with women. I think he felt that he could trust women producers more with his money. He took it for granted that men will always steal a little, but women wouldn’t even think of it.”

AMY HOLDEN JONES: “When I did Slumber Party Massacre, there were women throughout that crew. All over the place—A.D.s, electricians, all kinds of things. When I walked on set the first day to direct it, I didn’t have any feeling like ‘Prove yourself. You’re a woman.’ ”

DEBORAH BROCK (director, producer; post-Corman credits include Honey, I Blew Up the Kid): “When I first went to work for Roger, I didn’t know if there was any hope of me ever being able to be a director because the sexism in Hollywood was so intense. But the more I worked for Roger, the more I realized, ‘Yeah, I could do at least as good a job as any of these male directors were doing on his films, and probably better.’ I had to learn to deal with much more sexism and stuff after I left Roger’s.”

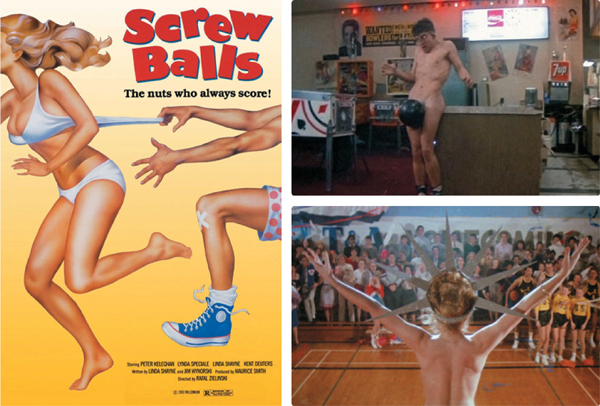

JIM WYNORSKI: “I wrote three films for the Cormans in the early eighties: Forbidden World, Sorceress, and Screwballs. Screwballs was a huge hit for him. I think everyone thought of it as an unfunny film from Canada. But I kept telling Roger, ‘I think this is going to work, I think this is going to work.’ They had no hopes for it. But it saved him in 1983. That’s when I left the advertising business, after I did the poster for Screwballs. I actually stole the idea for that poster from MAD magazine. Never got caught, though.”

U.S. poster and frame grabs from Screwballs (1983), directed by Rafal Zielinski. Wynorski knew how to sell this post-Porky’s Canadian teen sex romp, thanks to an inspired poster that he admits he stole from MAD magazine.

JOHN SAYLES: “In the mid-eighties, Roger sold New World. As part of the deal, he had to stay out of the business and couldn’t compete for a year or two. When he got back into business with his new companies, New Horizons and Concorde, it had changed. Suddenly, his business became more of a video business.”

FRANCES DOEL: “Why did Roger sell New World? I suspect it was one of those offers that was too good to refuse. And it’s not like he stopped. He just went off and started a new production and distribution company.”

DEBORAH BROCK: “I first met Roger when I was writing a paper about him at UCLA Film School. I think the subtitle of it was ‘The Producer as Auteur.’ Later, a friend of mine who worked there said they were looking for someone in the post-production department. It’s very interesting how the job interviews went at Roger’s. The first thing that the head of post-production said to me was ‘I want to tell you about a job you probably don’t want.’ And then he proceeded to tell me everything horrible about working for Roger’s company. The pay was abysmal, the hours were extremely long, and you were going to be working in a very funky office at this former lumberyard in Venice. The ending line of this rant was ‘Do you still have any interest?’ And I said, ‘Oh, yeah!’ I was an assistant editor, and we were doing all these trailers. There was an enormous amount of product going through the company. Roger would get these films that were shot in other countries like Argentina or the Philippines and they had problems, so we would have to recut them. Working for Roger, you got over any fears you might have had about ‘Oh my God, this is art. I can’t touch it.’ In fact, you realized on a lot of his films that there wasn’t anything I could do to make them worse. Roger would get into these payroll-cutting moods. When he would come to the lumberyard, he would park in the parking lot out front. And you know, the receptionist would see him, and she would immediately call around on all the extension phones to the different departments to tell people that Roger was there. And everyone would take off and go get some coffee at a nearby cafe, so Roger would not see them. Because if Roger saw too many people, he would want to let people go. So half the population of the studio would just disappear the minute he walked through the door. I’m not saying he was neurotic about money, but this is a man who saved little short pencils and unmarked stamps.”

U.S. poster for Barbarian Queen (1985), directed by Héctor Olivera. Just as he sent his crews to the Philippines in the 1970s to capture exotic new locations at a discount, Corman set his sights on Argentina for this rollicking ancient Roman adventure starring Lana Clarkson and future Corman director Katt Shea.

KATT SHEA (director; post-Corman credits include Poison Ivy and The Rage: Carrie 2): “I was teaching blind kids in a Detroit high school in a really tough neighborhood. I wanted to try something new, so I drove out to Hollywood in my Volkswagen Beetle. I didn’t really go with the intention of acting, but I got an agent and started going on auditions that had nothing to do with talent. It only had to do with how I looked. I was sent on an audition for a Roger Corman movie, and I didn’t get the part. They actually hired somebody else, but then that actress got a TV pilot, and I was the next in line. It was for Barbarian Queen. I went to Argentina for two and a half months to shoot that. It was a ridiculous sword-and-sandal movie. It was just a wild time. I was one of the barbarian girls in a skimpy little outfit along with Lana Clarkson. She was a very strong girl and very much wanted to be a big, big star. She definitely saw it as her big break. We have our big hair and Cover Girl makeup on. I see the pictures now and I go, ‘Why would they do that to me?’ It was so ridiculous, you just have to laugh and do your best. The whole time I wasn’t participating in anything movie-wise, I was asking questions and trying to figure out how they shoot things and how do they decide how to shoot it, and what was their inspiration, and asking the cameramen what kind of lens they were using and why, and all that kind of stuff. After I got back, I started writing screenplays.”

JIM WYNORSKI: “They were doing a very high-run, cranking out a lot of movies by this time. And they asked Julie Corman to do a film about a killer in a mall. And Julie walked into my office, which was right across from hers, and said, ‘How about a script about a killer in the mall?’ And I said, ‘If I can direct it, I’ll write one for you cheap.’ And she said OK. That turned out to be Chopping Mall. Everyone claims that I stole that idea from this James Brolin TV movie from 1974 called Trapped. He’s trapped in a mall with some vicious guard dogs, and they’re trying to get him. But I never saw it. What I did see was a 1954 movie called Gog about an underground army base somewhere in Arizona that had four or five levels, and it was all run by computer. The computer gets sabotaged, and everybody in this underground complex is trapped. And they have these two robots—very much like my robots, except there’s two instead of three. And the robots go chasing people throughout this underground complex. I loved it when I was a little kid. And I said, ‘You know what? Let’s go take that.’ So we kind of did our own version of Gog, called Chopping Mall. I learned a lot from Roger on that film. He would look at a cut and he’d say, ‘You know, cut a few frames here. Cut a few frames there. Add a frame here, add a frame there.’ And you’d think, what difference is that going to make? But it makes a huge difference when you’re watching the thing. It’s a visceral thing. He had a very keen mind about what constituted a good pacing for a picture.”

Frame grabs from Barbarian Queen (1985). Katt Shea and Lana Clarkson as avenging she-warriors. Says Shea of her teased hair and Cover Girl makeup, “I see the pictures now and I go, ‘Why would they do that to me?’”

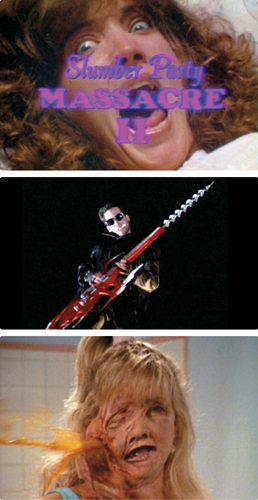

DEBORAH BROCK: “Roger had sold New World a few years earlier, and his company was now called Concorde. Well, I got offered a job from the guys who had bought New World from him. I went to Roger and told him about it, hoping to maybe use it as leverage to direct. I asked Roger what he thought. And he said that the guys over at New World were a bunch of lawyers who didn’t have any idea what they’re doing. He said, ‘Oh no, don’t go over there. They’ll be broke in eighteen months.’ And I said, ‘Yeah, but, you know, I don’t want to be the head of post-production forever, I really want to write and direct.’ And he looked at me and he said, ‘Well, I have a film you can write and direct right now. It’s called Slumber Party Massacre II, and I sold all the European rights based on the title alone.’ He was so proud of that. The whole film had been presold, and there wasn’t even a script, just a title. I had never been a big fan of horror films. And then he told me I would have to write it, too. Looking back at the film, I think it’s very subversive. It was banned for years in the U.K. They sent Roger a letter saying that it couldn’t be distributed there because of a particular virulent combination of rock and roll music, violence, and sex. And I thought, Ooh, those guys are really square, but at least they got it.”

Frame grab, U.S. poster, and photo of Jim Wynorski from Chopping Mall (1986), directed by Jim Wynorski. Machine-fueled manslaughter makes its way to the galleria in Wynorski’s tongue-in-cheek critique of American consumerism.

U.S. poster for Stripped to Kill (1987), directed by Katt Shea. A serial killer is murdering strippers. So, naturally, a female cop (Kay Lenz) goes undercover to sniff out the madman, one lap dance at a time. You’re either the audience for this kind of movie or you’re not. But having Mr. Roper (Norman Fell) in the cast certainly sweetens the deal.

KATT SHEA: “Andy Ruben was my husband and writing partner at the time. We were having dinner one night, and he told me that mussels were poisonous at certain times of the year. I thought he was just screwing with me, because I’d never heard that before. So we made a bet, and if I lost, I would have to go to a strip club with him. I didn’t want to go and see these women being exploited. But we went to The Body Shop, and I fell in love with it all. The girls were just so amazing. I said, ‘We have to make a movie about this!’ So Andy and I came up with the idea for Stripped to Kill. I approached Roger about it—actually, I waited outside of his office for him to come out for lunch one day and ‘accidentally’ bumped into him. I said, ‘Roger, I’ve got this fantastic idea for a movie, and it involves strippers! You’re not gonna believe it, they fly around this pole, and here’s what the poster will look like!’ And his eyes are just getting bigger and bigger. So he says, ‘Come into my office Monday morning.’ Andy said to me, ‘When you pitch him, tell him you’re gonna direct it.’ And unbelievably, Roger was open to it. In the movie, one of the strippers is actually a guy in drag, and Roger didn’t think we could pull that off and have it be convincing. So I brought in a female impersonator from La Cage aux Folles, and he explained to Roger what he does with his package when he wears a G-string. And he went into such detail that Roger was turning purple, and he says, ‘Just get out of my office! You can do it, just get out!’ ”

GALE ANNE HURD: “When I was there in the late seventies and early eighties, it was still boom times. But by the mid- to late eighties, it really started changing. It was getting harder to get theaters to play the lower-budget films, and the cost of marketing just went up exponentially. You couldn’t compete against the big studios and win. The emergence of VHS is what saved the company.”

JOHN SAYLES: “Drive-ins were closing, so no one needed those second and third features anymore. The kind of culture where you’d go to the drive-in and make out and half-watch the movie was ending. There just wasn’t a market for B pictures anymore. More and more often, even if it was a one-screen theater, they just played the same big-studio movie over and over again, they didn’t have a double feature. The booking policies had changed, and so I think that he was really just feeling like God, I’m making the same stuff, and it’s not that people don’t like it, but I just can’t get it on a screen. That was just a reality. There’s not much you can do about it. So I think at first he just tried to start making movies cheaper—let’s make this as fast and cheap as possible, and there’s got to be a spin-off. Things were changing, and those movies were becoming video-only releases. But it saved him, because the big studios were slow to pick up on the change in the industry. They’re kind of like big dinosaurs that can’t move very quickly. The smaller animals like Roger were able to adapt quickly to the new environment.”

ROGER CORMAN: “As the theatrical market for low-budget pictures began to fade I could see that our theatrical grosses were dropping, and we had to turn to something else out of necessity. The first thing was VHS and cable. When HBO started, for their first year we were their biggest supplier. But VHS was really the savior. It became our major source of income. The major studios were slow to adapt because they thought video was going to be a competitor to theatrical. And it was.”

Frame grabs from Slumber Party Massacre II (1987), directed by Deborah Brock. In a genre known for its cruelty to women, here’s one where every chapter was directed by one. Writer-director Brock hit all the horror-movie beats in this sequel, but she also goosed things along with humor, including a rockabilly villain whose drill doubles as a guitar and a prom-queen type whose face turns into a Clearasil ad gone wrong.

FRANCES DOEL: “It’s always been remarkable how Roger has been able to adapt. From the time he started producing and directing in the fifties and into the sixties, he would think, Is there something that they’re not doing that I can do? He doesn’t look just at what people are doing and what the audience seems to be responding to, but he’s always been interested in looking at what’s going on in society. What’s changing? That’s how The Wild Angels and The Trip came about. In later years, in the eighties and nineties, the kinds of films he had always made were being made by the studios, from Jaws and Star Wars on—the same kinds of exploitation films but with bigger budgets and much better effects and better scripts and better acting—and he had to respond to that. If he was going to keep going, he had to find more and more creative ways to work in a low budget. So he found places to shoot on a budget cheaply—the Philippines, Argentina, China. He’s always had a tremendous curiosity in other places. I remember he told Francis Coppola that he’d chosen the wrong time to shoot Apocalypse Now in the Philippines.”

DEBORAH BROCK: “When Roger saw he couldn’t compete with an exploitation film that a major studio spent millions of dollars on, he decided that it didn’t matter if they had theatrical. But that really upset his staff. We wanted to see our films on the big screen. Or even a drive-in.”

KATT SHEA: “I kind of missed out on the whole theatrical thing. I came in after that. When we were shooting Dance of the Damned, he came down to the set and said he wanted me to do Stripped to Kill II with the same set. I’m sure he was sitting at his desk and a lightbulb went off and he said, ‘I have a nightclub set; I can get Stripped to Kill II out of it.’ We were shooting Dance of the Damned in Venice at the lumberyard, and I think we finished shooting that on Friday and started Stripped to Kill II on Monday. We had to cast it over the weekend. My assistant on Dance of the Damned was Eb Lottimer. So he became the star of Stripped to Kill II, and Andy found Maria Ford in a club over the weekend and we cast her. I had Monday to Friday to shoot everything that would take place in the nightclub before they tore it down, even though it hadn’t been written yet. I threatened to take my name off every movie I did for him! At the end, he would be driving me so crazy with the editing and putting more boobs in and everything, I would go, ‘OK, Roger, I’m taking my name off!’ ”

J. B. ROGERS (director, producer; post-Corman credits include There’s Something About Mary and American Pie): “When I was in college I saw The Terminator, and it struck me—I know this is a is a stupid thing to say—but it struck me that people actually get to do this as a job! I was supposed to go to law school, but instead I drove out to L.A. and got a bunch of production-assistant jobs, including a few on Joe Dante movies like Innerspace and The ’Burbs. After a while, Joe was like, ‘OK, man, you’re doing great here and this is all wonderful, but honestly there’s nowhere for you to go. You’re just kind of stuck being a P.A.’ He told me about Roger Corman, saying, ‘This is a place where you can go and get a lot of experience, and if you can make it work there, you can kind of make it work anywhere.’ So he recommended me to Roger. I went over there and got in the door on a movie directed by Jim Wynorski called Transylvania Twist. Wynorski’s a crazy man. He used to wear a kimono on set and sit there directing some strippers he’d picked up at a bar the night before. His specialty was these soft-core horror films. At one point Roger had a couple of movies going on a set he had built of a suburban house. And I was with Wynorski in the office on a Thursday, and he got a call from Roger, who says, ‘Can you come up with a script by Monday and start shooting on Wednesday and have it done by Friday?’ He just wanted to try to squeeze one more movie out of this set. Jim hangs up the phone and goes, ‘You got any ideas?’ And I’m like, ‘Uh, a sorority house?’ And so Jim and I wrote the script for Sorority House Massacre II over the weekend. It wasn’t hard if you stuck to the formula: You’ve got your shower scene, you’ve got your crazy guy who lives next door, you’ve got the twist at the end. And then you just got a bunch of girls and you put them in lingerie. You just pound it out. We ended up shooting that thing in three days—just so Roger wouldn’t have to tear down the set! I think I played a pizza delivery guy in that one. No, that was Tower of Terror. I played ‘House Cop #2.’ I come into the sorority house after the guys murdered all the girls, and discover the bodies.”

Frame grabs of hands on a hard body from Stripped to Kill (1987); Maria Ford’s lap-dancing heroine Shady is haunted by harrowing nightmares in Stripped to Kill II: Live Girls (1989), directed by Katt Shea.

Photo from the set of Deathstalker II (1987), directed by Jim Wynorski. Wynorski poses with his stars, Monique Gabrielle and John Terlesky, on the Argentine set of Deathstalker II. Adapting to the meteoric rise of the VHS market, Corman bypassed theaters altogether and shipped the fantasy film straight to video. The medium didn’t matter as long as the message was money.

JIM WYNORSKI: “In 1989, Roger went on a vacation with Julie. I said to Julie, ‘Let’s make a movie behind Roger’s back. While you’re gone, I can make it in seven days.’ And she said, ‘OK, I’ll finance that, but don’t tell Roger, because he’ll get mad.’ So I wrote a script in three days to be made on sets that already existed. I was calling it Nightie Nightmare, which is a good exploitive title. I made the film in a week while they were gone. When they got back, I got a call from Roger: ‘Jim, can you come in? I need to talk to you.’ I walk into his office and he says, ‘I’ve heard rumors that you did a film in a studio while I was gone.’ I didn’t know what to say. I said, ‘Yes, I did, Roger. Your wife, Julie, financed it.’ He said, ‘That is incredible that you did it in such a short time. What is it?’ I said, ‘It’s a slasher movie.’ And he said, ‘Well, can I see it?’ So, he watched it and called me that night from his house—which he rarely did—and he said, ‘You know, I want you to do it again for me. Use the same set, use the same actors if you want, but make the same movie for me.’ So I ended up making the same film twice. One’s called Sorority House Massacre II, and the other one is called Hard to Die.”

U.S. poster and frame grab from Not of This Earth (1988), directed by Jim Wynorski. What’s old is new again: Corman produced this remake of his 1957 B-movie classic about alien vampires who come to Earth in search of new blood. This time it’s Traci Lords who’s doing the screaming, in one of her first post–adult film breaks.

SID HAIG: “People always say, ‘You know, Roger Corman made four hundred movies and never lost money on any of them.’ Well, you know what? There’s a reason for that. The guy’s a genius. He’s a marketing genius. David Carradine and I did a film for him in 1989 called Wizards of the Lost Kingdom II. There was no Part I! The idea was that if it did well at the box office, we could make Part I cheaper, and release it by popular demand. That is absolute genius! We still had two weeks of filming left, and he quickly put together a two-minute trailer from the stuff that we had already done. That weekend he went to Italy and came back with a check for seven figures.”

U.S. poster for Sorority House Massacre (1986), directed by Carol Frank. A concept so obvious, it’s shocking that it took so long to get around to it. Wynorski and J. B. Rogers would waste less time with the 1990 sequel. They wrote it over a single weekend and shot it in three days.

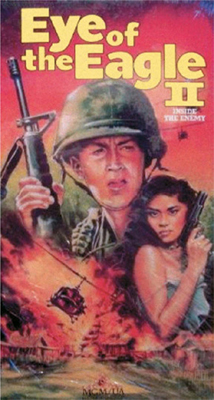

CARL FRANKLIN (director; post-Corman credits include One False Move and Devil in a Blue Dress): “I was a film student at AFI, and some of my tapes made their way to Anna Roth, who worked for Roger. Roger was doing about six or seven movies a year in the Philippines with Cirio Santiago, his Filipino producer. They offered me the chance to go over and shoot a war movie called Eye of the Eagle II. He gave me three days to come up with a treatment. And then they gave me three weeks to write the script. And then I was on a plane to the Philippines. It was all very quick. I was familiar with Roger’s name from some of the Vincent Price movies from the sixties. But I didn’t have any idea that people like Coppola and Scorsese and Ron Howard had come through there. When I first met Roger, he had this ten-minute speech about how to make a movie that I guess he gives to everyone. Ten minutes! One of his tips was if the DP says he’s got it, he’s got it. I obviously had some butterflies because I had never made a feature-length film before. But there was also this incredible sense of freedom because he wasn’t leaning on you. We had one of those old 35mm Mitchell cameras. They must have shot Gone with the Wind on it! Roger had a deal to make movies in the Philippines, and he had access to helicopters and military equipment, so he could shoot Vietnam pictures there. Apparently there was a big Asian market for those because they had a big body count and a lot of gunplay and action.”

Video cover for Eye of the Eagle II: Inside the Enemy (1989), directed by Carl Franklin. Franklin was fresh out of film school when Corman sent him to the Philippines to shoot this low-budget war flick with Todd Field. Franklin loved the quick pace and the sense of freedom Corman gave him. But the creaky, beat-up equipment he was given to shoot the film left a lot to be desired. “We had one of those old 35-mm Mitchell cameras,” says Franklin. “They must have shot Gone with the Wind on it!”

Poster for Silk II (1989), directed by Cirio H. Santiago. Straight-to-video starlet Monique Gabrielle plays a cop in Honolulu hot on the trail of art smugglers who’ve stolen a priceless “Asian scroll.” You’d never guess from the poster that she was so interested in antiquities.

TODD FIELD (actor, director; post-Corman credits include In the Bedroom and Little Children): “Carl offered me the lead in Eye of the Eagle II: Inside the Enemy. These Vietnam genre things started as a horrible rip-off of Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket and then went on to become something horrible in other equally un-original ways. Three weeks later, I was in Manila being filmed running around a military obstacle course by a huge camera being operated by a Filipino DP whose training, I was told, involved a lot of Quezon City porn. The producer was the infamous Cirio Santiago, one of Roger’s guys and an amazing character. He showed up one day when the production shut down because all the props went missing and asked if I wanted to go with him to the races. His driver took us to the Manila Jockey Club, and I followed Cirio upstairs to the owner’s room and he asked me who I wanted to bet. Bam! That horse came in!”

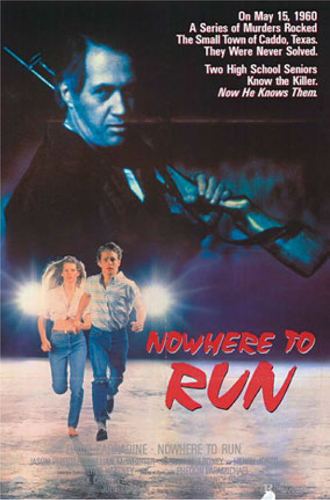

CARL FRANKLIN: “Did Todd tell you that he didn’t realize what was happening, so he kept betting on his own horses? Cirio was trying to tell him, ‘No bet on this horse!’ Not realizing that he had the race fixed? Almost right after that, I made Nowhere to Run with David Carradine. He was very colorful. He’s dead now, but David obviously had a problem with alcohol, and sometimes we had a six A.M. call and he would already be reeking. I was rewriting scenes all the time and I would give him a new three-page scene, and he would look at it once and have it. He was remarkable. I think that the films that Cameron and Scorsese worked on for Roger were better than the ones we were doing because they were actually going to theaters instead of straight to video. I mean, the submarine set we had on Full Fathom Five was made out of Cadillac parts and cardboard. A heater was used as an intercom. They wouldn’t stand up in a theater with an American audience. But man, just to come out of film school and to have someone put some money behind you and let you go out and expose film and shoot. Nobody does that anymore. I went out and shot three features in a year and a half, and it really gave me a lot of confidence. We shot Full Fathom Five in Peru. Todd was in that one, too. He’s crazy. We had already been in the Philippines together and had been through some stuff there because the revolutionaries were getting active. Todd was dressed as a GI for the film, and we came to a checkpoint, and they made him totally strip and they gave him a hard time. So when I called him to come along to Peru, he was like, ‘Oh, man, my wife just had a baby.’ Peru is even worse than the Philippines, and the Shining Path rebels were active at the time. There was definitely a chance something could happen to us. Anyway, after discussing it for a while, I said, ‘Are you coming?’ And he said, ‘Sure.’ ”

TODD FIELD: “The story was supposed to take place on a submarine. I researched the part meticulously, spending time at a naval base down in San Diego. But when I arrived in Peru, the set consisted of little more than painted cardboard boxes with little Christmas lights sequenced on dimmers. Carl said not to worry, he was going to just frame everything tight. But as soon as he said ‘Action,’ I burst out laughing—the kind of laugh that doesn’t stop. Afterward, I ran into Michael Moriarty, who was also in the movie. He asked, ‘What happened in there?’ I told him that when I looked up at that set and those stupid lights, it suddenly hit me how ridiculous it all was, and how ridiculous I was, and how was I ever going to be able to tell my daughter what her father really did for a living.’ Michael nodded and said, ‘You just figured that out now?’ I remember driving out to the Valley with Roger and Carl for a preview of Full Fathom Five—a preview with hundreds of people for a film that was going straight to video. I also remember buying a tub of popcorn and Roger reaching over with his hand and stealing half of it without so much as a look in my direction.”

Video cover for Nowhere to Run (1989), directed by Carl Franklin. Even after a few rise-and-shine drinks, David Carradine could look at his lines once and have them down.

U.S. poster for Full Fathom Five (1990), directed by Carl Franklin. A submarine thriller, Corman style: The sets were made out of old Cadillac parts and cardboard. The ship’s intercom was fashioned from a space heater.