5

FROM MAVERICK TO ELDER STATESMAN

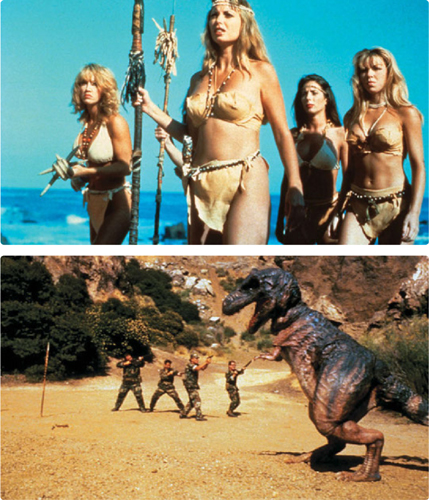

Still from Dinosaur Island (1994), directed by Jim Wynorski and Fred Olen Ray.

IN 1990, ROGER CORMAN’S two-decade absence from the director’s chair finally ended. He agreed to return for Roger Corman’s Frankenstein Unbound, an $11.5 million 20th Century Fox production based on Brian Aldiss’s novel. With its Lake Como, Italy, locations and a $1 million paycheck for the gig, Corman once again relented to an offer too good to refuse. With an impressive cast that included John Hurt, Raúl Juliá, and Bridget Fonda, the sci-fi take on the Mary Shelley gothic horror classic seemed like an ideal companion piece to Corman’s early sixties Poe films. But the movie was a commercial disappointment. Surely, he must have been heartbroken. But even his closest employees at the time admit they never saw him mope or dwell on the failure. He wasn’t the kind of man who wrings his hands with regret or missed opportunities. Instead, Corman returned to his office at Concorde–New Horizons and resumed his role as a Hollywood’s busiest producer.

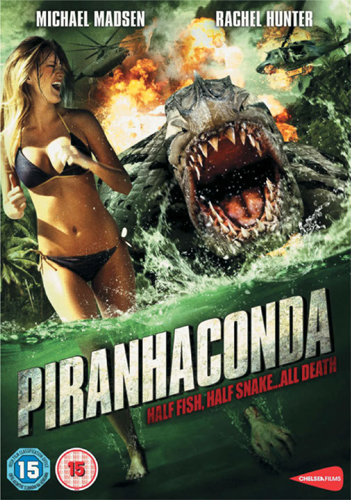

As the VHS market continued to chug along, giving birth to a new kind of second-tier, straight-to-tape action star like Don “The Dragon” Wilson, the marquee attraction behind Corman’s Bloodfist franchise, Concorde–New Horizons was churning out product at a dizzying pace. Not only was Corman finding time to provide cameos in films made by some of his magna cum laude graduates (Jonathan Demme’s Philadelphia, Ron Howard’s Apollo 13), he was also managing to produce as many as twenty titles a year by the mid-nineties, thanks in part to a sweetheart deal with Showtime to create a series of original films under the “Roger Corman Presents” banner. Most of these films were remakes and riffs on older Corman properties with a strong cult brand awareness, such as The Wasp Woman, Not of This Earth, and A Bucket of Blood. In fact, the cable market was so financially tantalizing, Corman reached into his own pocket to bankroll a female crime-fighter TV series based on his steamy 1995 movie Black Scorpion—the film starred Joan Severance as leather-bondage-gear-wearing vigilante; the TV series passed the torch to former beauty queen Michelle Lintel. It ran on the Sci-Fi Channel in 2001. Years later, after the network gave itself a branding makeover and renamed itself Syfy, Corman would become one of its biggest providers of original programming with his giddy, low-budget monster flicks like Sharktopus, Piranhaconda, and Dinocroc vs. Supergator.

By the early 2000s, with his former protégés now off winning Oscars, Corman seemed more shocked than anyone to discover that he had somehow come to be regarded as a Hollywood elder statesman. The former maverick, who would have once scoffed at being feted by the establishment (unless they were willing to pick up the tab), was now being considered for an honorary Oscar. The graduates of the University of Corman, now bona fide members of the clubby major studios, began petitioning the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences for Corman to be brought into their rarefied circle. History had shown that he’d already won the revolution; why shouldn’t he enjoy the gold-plated spoils as well? When the Academy finally honored Corman with a lifetime achievement statuette in 2009, it cited the then-eighty-three-year-old’s “unparalleled ability to nurture aspiring filmmakers by providing an environment that no film school could match.”

That night, as the King of the B’s walked onto the dais to accept the award with a frisky grin on his face, it was clear to everyone watching—Ron Howard, Jonathan Demme, Jack Nicholson, Julie—that there was no need for a rewrite. This was the sweetest third act Roger Corman could have ever written.

Publicity photo from the set of Frankenstein Unbound (1990), directed by Roger Corman. Back behind the camera (and for a major studio!) after a nearly twenty-year absence, Corman discusses what he wants from stars Bridget Fonda and John Hurt.

MARTIN SCORSESE: “I think Roger always backed away from the idea of being taken seriously as a director. He says that he didn’t understand what anybody was talking about. Then, in the early eighties, I met him at a dinner in New York, and I asked why he wasn’t directing anymore. He said, ‘You know, when I see the films that are being made now, like Toolbox Murders, where they’re using drills to carve people’s heads, I don’t do that.’ ”

F. X. FEENEY: “I think that the directing bug never really left Roger. I think there was a point after Von Richthofen and Brown in 1970 where he thought, Let someone else handle the grunt work of directing. He’d had some bumpy experiences dealing with big studios, like on The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, and it rubbed him up against the realities of the business. I think he got more enjoyment as a guy who directed directors. It’s funny about Roger, because he comes out of engineering—and an engineer likes to stand above things and see how they operate. Roger loves to watch the operation from a height. And I think he enjoyed the ant-farm aspect of producing, where he could watch a lot of films get made and direct the directors.”

THOM MOUNT (producer; former head of Universal Pictures): “Like a lot of other people, Roger started me in the movie business. I knew some guys who worked for him—Joe Dante and some others. So I went to work there in 1972 for $80 a week, in cash. On Monday, you’d lug cable in a pickup truck, on Tuesday you’d be a first A.D. if the A.D. didn’t show up, on Wednesday you’d have a speaking part because an actor didn’t show up and Roger didn’t want to pay a replacement, and on Thursday, you’d be working on a one-sheet in his office. If Roger thought you were smart, he’d work the hell out of you. All of the movies were the same: The car came around the corner of an alley and ran into some trash cans, someone shot a gun, and someone else dropped off the roof into a Dumpster. Then the Playmate of the Month took her top off. Cut. Wrap! I always felt that I owed Roger. So when I started thinking about making Frankenstein Unbound, I thought, Let’s get Roger to direct this thing. He hasn’t directed in twenty years! We paid him a million dollars to do it. It was a nice chunk of change. And we shot it in a beautiful part of Italy. It was a thrill to see him back behind the camera. He had a thirty-day schedule, and I don’t think he’d ever had thirty days to make a film in his life! He would say to me, ‘Thom, if we finish this early, do we get to keep the money that we save?’ And I was like, ‘Spend the fucking money, Roger!’ ”

Frame grabs from Frankenstein Unbound (1990). Nick Brimble fresh out of the makeup chair as the mate-seeking Monster; John Hurt hits the road as Dr. Joe Buchanan, a brilliant scientist who gets sucked back in time to the early nineteenth century—an era of unlimited creation, be it from the minds of romantic poets or mad scientists.

F. X. FEENEY: “When I knew I was going to work with him on Frankenstein, I thought, I’ll get to work one-on-one with the master. And working one-on-one with the master turned out to be a very interesting thing, because when I went in, it was Roger and two of his employees flanking him. We sat down and talked through where the story should go, and he said, ‘I’ll need ten pages by tomorrow morning.’ The next day, I brought in the ten pages, and the three of them were all reading the pages in front of me. I’m just sitting there, listening to the flicking of the pages. And then one of his people says, ‘Well, Roger thinks that on page five … .’ She just knew his mind. And then the other one did the same thing. And I would look at Roger, trying to make eye contact with him, and he was Mr. Inscrutable. Others have said this: When you pitch him something, there is a face that he puts on that is Dr. No. He will not react. It’s the great stone face. And it’s a deliberate mask that he puts on, and it actually helps you perform because you’re just hoping to get a flicker.”

Frame grab from Frankenstein Unbound (1990). The Monster discovers his Kryptonite: intellectuals waving torches.

JONATHAN KAPLAN: “I’m Roger’s biggest fan, but I don’t know if I could say that I really know him. What I got from him was that he really wished he could express stuff that he couldn’t express. Roger’s happiest moments are when he’s telling a story about how he pulled a fast one on this one or that one. His eyes crinkle up and he laughs this hearty laugh. That’s the real him. I think the reason why Roger stopped directing is that he’s too dignified to go and beg. He’s not going to go and fight for the job after all that he’s done.”

F. X. FEENEY: “I thought the film was about Roger wanting to win an Oscar. I don’t think it takes anything away from him to say that. Roger has said that Frankenstein Unbound was a painful experience for him. That surprised and saddened me, but I can see why, because it didn’t work out. It didn’t get the release that we all wanted for it. It didn’t bear fruit the way Roger had hoped it would. It was like The Intruder all over again.”

Roger Corman’s Frankenstein Unbound 1990

After his disappointing experience behind the camera on 1970’s Von Richthofen and Brown, Roger Corman decided to take a break from directing. Initially, he thought the hiatus would be for a year or two. It ended up being twenty. Then, in 1990, Corman was offered one million dollars to helm 20th Century Fox’s Frankenstein Unbound. How could a man like Corman not have been flattered by both the enormous payday and the attention from a major studio—the very sort of Hollywood club he’d always felt excluded from?

Based on Brian Aldiss’s novel, and adapted by Corman and film critic F. X. Feeney, the Promethean tale seemed like a natural fit for the Poe aficionado’s gothic horror sensibilities. Not to mention that he would be given the opportunity to work with an A-list cast and a budget bankrolled by Rupert Murdoch. The film opens with a irony-soaked voiceover delivered in John Hurt’s sandpaper rasp: “After the first atomic bomb, Einstein said, ‘If I had known where this would lead, I would have been a watchmaker.’” The year is 2031; the setting is New L.A. Hurt plays groundbreaking scientist Dr. Buchanan, who gets sucked into a disco-lit rip in the space-time continuum while testing his latest atomic weapon. Suddenly the good doctor, decked out in a sparkly silver jumpsuit, and his super-intelligent, Knight Rider–esque talking car, are transported to Lake Geneva in 1817. At a local pub, he meets Raúl Juliá’s Baron Frankenstein—another man of science, whose mad, top-secret experiments in creating life are well known to Buchanan. His suspicions are confirmed when he follows Frankenstein home and spies him arguing with his monster (Nick Brimble, under a thick coat of latex putty and sutures).

Frankenstein needs Buchanan’s twenty-first-century know-how to animate the monster’s gruesome bride, and here the film lapses into a Back to the Future–style detour about using Buchanan’s hi-tech car (and a bunch of cool-looking Tesla coils and whirring machines) to electrify his experiment. After it succeeds, Buchanan and the monster are sucked back through a “time slip” to a “frozen tomorrow”—a lifeless Arctic tundra sometime in a post-apocalyptic future, where they face off and Buchanan comes to the realization that he is the real monster.

Frame grabs from Frankenstein Unbound (1990). Catherine Rabett plays Dr. Frankenstein’s fiancé, who’s later reanimated as a reluctant mate for the Monster; a rip in time delivers John Hurt (and his futuristic sports car) into the past; it looks like someone’s not too jazzed about becoming the Bride of Frankenstein.

When Frankenstein Unbound hit theaters in November 1990, critics welcomed Corman’s return. The film may not have had the same haunting sensuality and lush, high-threadcount cinematography of his eye-candy Poe pictures, but there he was, back in the game after all those years. It would have been churlish not to celebrate that. Still, Frankenstein wound up being a box-office disappointment due to a half-hearted marketing campaign and a limited release. Corman fans got their hopes up that Frankenstein would signal a second wind for the director—that he might kick off a new and productive chapter as an éminence grise auteur with more late-period works up his sleeve. But they were left holding their breath. Corman hasn’t officially returned to the director’s chair since.

U.S. posters for The Unborn (1991), directed by Rodman Flender, and Watchers II (1990), directed by Thierry Notz. Former Harvard Lampoon writer John D. Brancato teamed up with Mike Ferris and cranked out Corman scripts like The Unborn and Watchers II. They quickly learned Corman’s two biggest pet peeves—profanity and voiceovers—a lesson they’d remember when they penned big-studio projects like David Fincher’s The Game and Jonathan Mostow’s Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines.

JOHN D. BRANCATO (writer; post-Corman credits include The Game and Terminator 3: Rise of the Machines): “I started writing at the Harvard Lampoon. It was a great place to hang out—crazy parties, you’d wear a tuxedo and drink too much. It was pretty wild. But a lot of the friendships that I made still haunt me to this day. An awful lot of people from the Lampoon wound up going to Hollywood. I started writing scripts with a Lampoon friend, Mike Ferris. We got along because we had similar record collections. We both liked really nasty hard-core punk music. I always liked killer mutant baby stories like It’s Alive, so we started writing a script, which became The Unborn. And around that time, I connected with Rodman Flender—another Lampoon connection—who worked for Roger. He read the fifteen-page treatment we did and said, ‘Oh, this is great. We’re going to make this movie. We have a set from another mad scientist movie. It’s only going to be up for a couple of weeks. But if you generate the script really quickly, we’ll make the movie right away.’ We started writing the script, and then Rod called back and said, ‘Oh, we struck the set after all. But Roger wants you to do Watchers II.’ The first Watchers was a Dean Koontz adaptation with Corey Haim. It was absolutely terrible. It’s about a genetically engineered golden retriever who’s psychically linked to this killing monkey-monster-thing. When I worked on Watchers II, I wasn’t a member of the Writers Guild, so we did it under a pseudonym: Henry Dominic. Mike’s middle name is Henry, and mine is Dominic.”

J. B. ROGERS: “We were just grinding these things out. If you could sell him on the idea that it will be rented in the video store, he would green-light it on the spot. And he’d put a great box cover on it.”

JOHN D. BRANCATO: “Roger was hilarious. His notes were always kind of minimal, but he had a few things … . like, for example, Roger really doesn’t like profanity or unnecessary dirty words, which is strange considering how much his work is exploitative. If you had a character saying ‘fuck,’ he’d draw a little red line through it in the script. The other thing he absolutely hates and will not allow is a character talking to himself. He said it’s never believable. No character should ever say a word when they’re alone. Good lesson. Oh, and he really didn’t like taking the Lord’s name in vain. Not bad notes. Those little maxims stay in my head to this day as a screenwriter.”

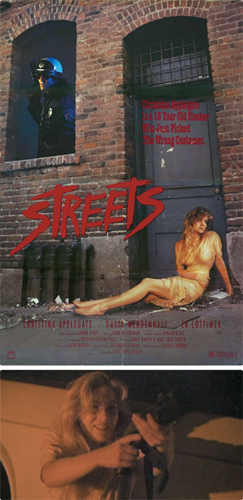

U.S. poster and frame grab from Streets (1990), directed by Katt Shea. Nineteen-year-old Married with Children star Christina Applegate takes a walk on the wild side as a troubled teen runaway hunted by a psychotic cop in Streets. Credit for the film’s artfully moody lighting goes to cinematographer Phedon Papamichael (The Descendants, Sideways, Walk the Line).

J. B. ROGERS: “My class at Corman University was very director of photography–heavy. Guys like Phedon Papamichael, who shot The Descendants; Janusz Kaminski, who became Spielberg’s DP; and Wally Pfister, who does all of Chris Nolan’s films. Your group stayed together for a couple of years, and then you would all move out and a new class would come in behind you. The beauty of working at Roger’s is you’re doing so many films in so many different genres—sometimes there was stunts, sometimes there was romance, sometimes there was an action sequence—it takes the fear away when you go on to make bigger films at a studio. You’re just like, OK, I’ve done that before. I’ve worked with a lot of first-time directors, and you just see this thing happen where they’re all confident and when they walk onto set on the first day and there’s two hundred people staring at them, you can just see them start to melt. But Roger’s was a good place to make mistakes. The guys forgot to load the camera, the special effects guy forgot to put a charge in the squibs. Things like that on a Corman film aren’t a big deal. But if you did that on a Jim Cameron set, you’re a dead man.”

U.S. poster for The Terror Within (1989), directed by Thierry Notz, and video cover for Body Waves (1992), directed by P. J. Pesce. Buxom beach bunnies and bloodthirsty space aliens—some film formulas age as gracefully as a fine Bordeaux.

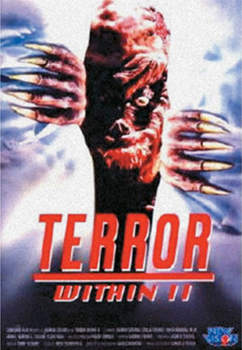

ANDREW STEVENS (actor, writer, director, producer; producing credits include The Whole Nine Yards and The Pledge): “I starred in a low-budget Roger Corman monster movie called The Terror Within. Roger was legendary to me even though I had never worked for him. After the movie came out, he called and asked me to come and meet him at his offices on San Vicente. He said, ‘I understand that you aspire to move away from acting?’ I said, ‘Yes, that’s correct.’ And he said, ‘The Terror Within did very well for us, and I would like to offer you the same deal I made with Ron Howard.’ I was all ears. He said, ‘I will allow you to write and direct the sequel to The Terror Within if you perform all three services you provided for the first movie.’ I wrote the script, I directed the film, and acted in it. This was all pre-CGI, and I asked him if we could buy some new monster suits because the monsters in the film were stunt guys in rubber suits. And these suits had been hanging in a hot warehouse for the past year and a half and they were melted and shredded. He said, ‘No, there’s no money for that, you’ll have to make do with what we have.’ I tried them on a couple of guys, and you could see their T-shirts through the suits. I thought, I’ve got to find a way to shoot these monsters where you only get a glimpse of them, like in Aliens. I was looking for a really talented DP, and I found an old videocassette with a strip of masking tape on it that said ‘Stripped to Kill: Second Unit’ and I put it in the VCR and I saw Maria Ford dancing totally frontally nude in a strip club. It was cross-lit, backlit, and diffused. You knew she was naked, but you couldn’t make out any distinct body parts. And I thought, This is the guy for my movie. So I called the kid in, and he was a young Polish kid. I offered him the job. He had never shot first unit before. But I knew he could shoot my monsters. He ended up winning the Oscar for Schindler’s List. It was Janusz Kaminski. When I showed Roger my cut of The Terror Within II, there was a scene where this monster’s finger is chopped off and falls down this underground hatch. Roger looked at it and said, ‘I think you need an insert of the monster’s finger falling through the frame. Because it looks to me as if you’ve cut the monster’s cock off.’ When I made the deal to do The Terror Within II, one of the conditions is that we would do a second picture together as a coproduction. The first film I made under that deal was Body Chemistry 3. And I think it was the first picture to go to CD-ROM at the time, and I think he made on a $300,000 investment about $1.4 million, so he gave me three more. Doing The Terror Within II was the best investment I ever made. It was a win-win for both of us, which is why we did something like twenty-six movies together over the years. On The Skateboard Kid 2, I got a call from Roger asking if I would give his daughter, Mary, a small part in the movie. He brought Mary to the set—she was twelve or thirteen at the time—and he left. I fabricated a role for her. And then we wrap, and I’m standing there on this set in the Valley with her. I finally reached Roger and he was out to dinner with Julie, and I took Mary in my car and walked her into the restaurant and handed her over to Roger and Julie. At least I didn’t have to paint his garage.”

Frame grabs from The Terror Within (1989). Future home-video mogul Andrew Stevens learned from the master on the Alien-inspired post-apocalyptic thriller The Terror Within. They would end up making more than twenty movies together in the go-go, mom-and-pop video shop era.

BRUCE DERN: “I ran into Roger about fifteen years ago. I saw him, and I said, ‘What’s going on with you now? What are you doing?’ And he said, ‘Oh, I’m coaching my son’s basketball team.’ Well, that made me shit a brick. Because this was a guy who was about as interested in sports as I am in worm farming. I couldn’t imagine Roger coaching his son’s basketball team, but he did it. I’m telling you, the guy was full of surprises.”

Video cover for The Terror Within II (1991), directed by Andrew Stevens. For his Corman-backed directorial debut, Stevens unearthed a mothballed tape of second-unit footage from Stripped to Kill and was impressed by the lighting style of the young cameraman with the unwieldy Polish name. Janusz Kaminski would later win Oscars for Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan.

Video cover and frame grab from Body Chemistry 3: Point of Seduction (1994), directed by Jim Wynorski. The story of the made-for-video era cannot be told without a nod to the kinky killer subgenre, the “erotic thriller.” Corman’s Body Chemistry series was one of the most lurid and lucrative.

Roger and Julie Corman and their daughter Mary at the off-Broadway premiere of Little Shop of Horrors (1982). Corman’s original film, shot in two and a half days in 1960, wound up spawning not only a long-running musical that continues to be revived but also a 1986 film, starring Steve Martin and Rick Moranis.

ANDREW STEVENS: “Roger was the first to realize that things were changing fast in the business. On The Terror Within, his deal was that he had to release it on a hundred screens as part of his video deal. But prints were expensive. So what Roger would do is he would strike maybe twenty prints and recycle them and move them around the country so he didn’t have to spend the money for a hundred prints. He was always finding ways. He grew up with the Arkoffs and people who had masterminded all of that before him. But he was someone who was able to reinvent and capitalize on things. In the early days of the VHS boom, anything on VHS cassette that reasonably had a beginning, a middle, and an end, you could pretty much double your money on. So everyone sort of made the lowest common denominator of crap. But a phenomenon occurred. The home-video star emerged: the Jeff Speakmans, the Mike Dudikoffs, the Don ‘The Dragon’ Wilsons. Don ‘The Dragon’ Wilson was someone Roger found and groomed into an action star for that direct-to-VHS market. I’ve done numerous Don ‘The Dragon’ films based on Roger having made him a viable entity. But it was Roger who took the risk first.”

Frame grabs from Bloodfist (1989), directed by Terence H. Winkless. Enter the dragon—Don “The Dragon” Wilson, that is. The Bloodfist series gave birth to the straight-to-video star.

FRED OLEN RAY: “Roger and Andrew Stevens made a deal where each one could use stock footage from the other’s movie libraries. So I’d make a movie and cut in some stuff from Piranha and Cyberzone and throw some stuff from Battle Beyond the Stars in there. And what’s that one with Yvette Mimieux? Jackson County Jail? I took a car chase through some cow pastures from that, and I put it in a movie called Bikini Hoe-Down.”

JOHN D. BRANCATO: “Another project we worked on for Roger was Bloodfist II, starring Don ‘The Dragon’ Wilson. We didn’t get a credit on it. The story behind that is a little embarrassing. We had other work starting around that time—actual Guild work that paid above scale. So we kept putting it off and putting it off, until the very last minute. And I wrote the script in four days. It was the quickest script I’d ever written and probably the worst. I remember writing lines like ‘a flurry of flying fists and feet.’ The basic premise was some billionaire captures kickboxers and has them fight to the death on some island in the South Pacific. Roger got the script, and he called Mike and me in. And he just looked very disappointed in us. He said, ‘I can tell your hearts aren’t really in this.’ He was right. We disappointed Roger.”

Video cover and frame grabs from Fire on the Amazon (1993), directed by Luis Llosa. Before she became America’s sweetheart, Sandra Bullock got steamy—very steamy—in the jungle with Craig Sheffer in a South American environmental thriller. There was no mention of the film in her speech when she accepted the Oscar for The Blind Side.

ANDREW STEVENS: “What eventually happened is stars like Don ‘The Dragon’ Wilson became too expensive after a while. They were making $600,000 per movie. I made movies with Dolph Lundgren, and he’d get $2 million, and as the budgets went down, we still had to pay him $2 million. So the problem was that the actors and their representatives who were looking for quick paydays were penny-wise, pound-foolish. The market continued to shrink from the mid-nineties until 2000. It was a slow death.”

JOE DANTE: “I don’t know that there’s a lot of classics during that period for Roger. There are some good works by some people who went on to do some other things, but I don’t think it was a particularly fertile period, because again he was sometimes remaking pictures three or four times. But if you have a slate to sell, you can’t necessarily expect that every script you get is gonna be terrific.”

JOHN D. BRANCATO: “Even though we thought that we’d burned the Corman bridge after our Bloodfist II experience, we actually did get around to making The Unborn with him in the end. It starred Brooke Adams and had Kathy Griffin and Lisa Kudrow in small parts. And Wally Pfister, Chris Nolan’s DP, is the cameraman on it. Bizarre, right? On the strength of The Unborn, Roger hired us to write an outline for Carnosaur. The idea was to beat Jurassic Park to the punch with a hundredth of the budget. The great thing about Roger is that he never got a swelled head, he never thought about making A-list movies. He never made the mistakes that so many other small companies made—of thinking that they would suddenly be able to eat with the studios. It was a brilliant strategy that guaranteed his long career. We never got beyond an outline on Carnosaur because we’d written a spec script called The Game, which David Fincher eventually made. Mike Ferris and I got paid $1,000 for our Carnosaur outline. But then we said, ‘Look, we really can’t do the screenplay because we have a commitment, we have to do these rewrites on this movie we just sold to MGM. But take the treatment, you don’t have to credit us or anything.’ And Roger said, ‘I want my $1,000 back.’ We were like, ‘But we gave you a treatment!’ He said, ‘Yes, but the treatment was with the understanding that you would do the screenplay. I want $500 back from each of you.’ I never paid him, but Mike did. I guess I still owe Roger $500.”

Frame grabs from Carnosaur (1993), directed by Adam Simon and Darren Moloney. To catch the runoff of Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park, Corman quickly put his own version in the pipeline. It even starred Jurassic Park star Laura Dern’s mom, Diane Ladd, thanks to a “very large check” from Corman.

DIANE LADD: “My daughter, Laura Dern, had just gone off and shot Jurassic Park. Well, Roger wanted to jump on that bandwagon with this movie he was producing called Carnosaur. Naturally, hearing about Laura, he thought about me. He didn’t go through my agent, he just called me and said, ‘I’m going to shoot the movie in two weeks, and this is what I want to pay you.’ I said, ‘I’m not going to do it, Roger. The Wild Angels was twenty-five years ago, and I’ve been nominated for Oscars. You’ve got to pay me.’ So he came up with a very big number. And this is how smart Roger Corman is: About an hour later my doorbell rang, and it was a messenger with an envelope from Roger Corman. I opened up the envelope, and there was a check with a lot of zeroes. There ain’t a woman in this world who wouldn’t cash that kind of check. I started to salivate. I went shopping, and Roger Corman had Diane Ladd. I mean, there’s a scene where I’m birthing a dinosaur in the movie! Hello! But he never treated it like it was silly. He allowed me to take it seriously.”

Frame grab from Carnosaur (1993). Diane Ladd does her best to keep a straight face as she births a baby dino—a scene that most definitely was not in Jurassic Park.

Photo from the set of Dinosaur Island (1994), directed by Jim Wynorski and Fred Olen Ray. “It wasn’t so much a Jurassic Park ripoff as a cavewoman movie,” says Wynorski. Tell that to the T. rex.

FRED OLEN RAY: “Dinosaur Island was the first movie I made for Roger. That was 1994. I’m a super fan. And if you’re a super fan, one of the things you really want to do in your life is to work for Roger Corman. I mean, to me, your career is unfulfilled unless you’ve worked for Roger. Just to have the meetings with him, having him watch your director’s cut and give you notes, and going through that process, and becoming part of that circle where you go to a wedding or somebody’s birthday party, and Roger and Julie are there, and you have kind of moved into that sort of area. So, going to work on a film where Roger was a producer—I would have almost paid him. Probably, in several ways, I have.”

U.S. poster and stills from Dinosaur Island (1994). Have you seen this Wynorski-Olen Ray guilty pleasure? Joe Pesci and Barry Levinson have.

JIM WYNORSKI: “After Jurassic Park came out, Roger got myself and Fred Olen Ray to direct Dinosaur Island. It wasn’t so much a Jurassic Park rip-off as sort of a cavewoman movie. Both Fred and I did that movie on a wing and a prayer. We shot over at Vasquez Rocks. We tried to do our level best. But Roger ended up hating the movie. He didn’t think the girls in it were pretty, and he thought the story was too campy. But it did really well. It only cost $190,000. Fred and I codirected. Fred would say, ‘I want to do these scenes’, and I’d say, ‘OK, I’ll go hang out with the chicks at the trailers.’ And then we would change off. He’d come back and I’d say, ‘OK, go ahead and take a rest, Fred, I’ll take over.’ We made the film in ten days. I thought it came out pretty well. The funniest thing is I was at a party and Joe Pesci—who I didn’t think even knew my name—came over and said, ‘Hey, Jim Wynorski.’ And I said, ‘Hi, Joe Pesci, right?’ He said, ‘Yes. I’ve got to tell you, I love Dinosaur Island! Every time I watch it, I feel like I want to go there.’ He was with Barry Levinson. And they kept asking me about Dinosaur Island. Bizarre.”

FRED OLEN RAY: “Roger’s not that forthcoming with information. Roger is very good at what he does because he’s always asking someone else what they think. There’s absolutely no value in Roger telling you what Roger thinks—he already knows what he thinks. His only value in talking to you is to find out if you know something that he’d like to know. I had a DVD company at the same time he was doing DVD, and you would go in and Roger would say, ‘Well, how many units of this are you doing?’ I’d say, ‘We did about five thousand units that time.’ ‘Really? We’re only doing two thousand units. Why do you think that is?’ He’s not going to tell you anything, but he wants to know what you know. I went over to pitch Attack of the 60 Foot Centerfold, and he has this glass desk and the chair that I sat in was a single piece of plexiglass, shaped like an S. It had no armrests on it, and no cushions. And I sat there, thinking This is probably the most vulnerable I’ve ever been—I’m sitting on an invisible chair, and he’s sitting there looking at me through this glass desk. And you think about it, and you go, What chance do you have to negotiate this deal with Roger Corman? I mean, you don’t. All you’re thinking is that you could fall at any moment! I’m sure it was a business ploy. There was a time there in the eighties where he was still hitting on all these cylinders, with Deathstalkers and movies he was making in Argentina. He had a lot of success with Don ‘The Dragon’ Wilson. I always thought Roger was probably the perfect combination of art and commerce. He wasn’t totally one or the other, but he blended them so well and seamlessly into the world of artistic expression, keeping an eye on the profit line at all times. And that’s something that I have always been interested in. He loved marketing. I really think that the business isn’t fun anymore. The fun of pulling a bold move, a maverick move, and succeeding in some crazy thing is probably what drives a lot of people. And I think that a lot of that has gone out of it. But Roger’s always been smart about finding the next thing. If theatrical dries up, go to video. If video dries up, go to DVD. If DVD dries up, go to cable networks like Syfy, like he’s doing now. Television is where we’re all really working now. There’s very little room for the little guy anymore.”

Promotional still from Black Scorpion (1995), directed by Jonathan Winfrey. Joan Severance stars as a masked crime fighter avenging the death of her father. Her superpower? Squeezing into that outfit.

Frame grab from Attack of the 60 Foot Centerfold (1995), directed by Fred Olen Ray. Actress J. J. North gets supersized in Olen Ray’s dizzy, ditzy romp about cheesecake models so hungry for fame they’ll do anything—even take experimental potions that turn them into gigantic Amazons. But how did North’s bikini top grow as well?

KATT SHEA: “After I made the Stripped to Kill movies and Streets for Roger, I went off and made Poison Ivy. It felt like I had graduated to the big time. But then I came back to make Last Exit to Earth. The thing that was hard about going back is just the lack of money and the struggle. People have no idea, the miracles that were created on nothing. I’m actually supposed to doing a remake of Dance of the Damned with Roger now. But you know what, if Roger’s the guy that you have to answer to for the rest of your life, there’s nothing wrong with that. You know where you stand with him. He’s a gentleman, and he’s honest.”

Photo from the set of Piranhaconda (2012), directed by Jim Wynorski. Wynorski and his mentor Roger Corman line up a shot for the SyFy monster movie Piranhaconda.

FRED OLEN RAY: “I was sitting in Roger’s office one day, and a kid comes in with some artwork for a movie called Dragon Fire—some martial arts film. And Roger looks at it and looks at it, and up at the top it says, ‘Best film of the year—Black Belt Monthly.’ And Roger looks at it, and he goes, ‘Tell me, is there such a magazine as Black Belt Monthly?’ And the kid says, ‘No, Roger, there isn’t.’ And he said, ‘Let me tell you, because we’ve got a few letters lately that there are photos on the backs of our DVD covers that are not from the movie that are on the DVD. We’ll have to be more careful about that in the future.’ I’m pretty sure he didn’t change the Black Belt Monthly quote, though.”

JIM WYNORSKI: “Roger’s always adapted to whatever the industry has thrown at him. But the past few years have been confusing to everybody. DVD has started to die. So the question is: Where do you go next? There’s the Internet, but you can’t make money on the Internet unless you’re Netflix. So, right now, he’s making movies for Syfy. I’ve done thirteen movies for them, including a couple for Roger, like Piranhaconda and Camel Spiders.”

JOHN SAYLES: “The Syfy channel has aggregated all of the audience for these monster movies in one place, and therefore their advertisers and their cable people who carry them say, ‘OK, people know what they’re gonna get when they go onto that channel, and so we’ve kind of done this narrowcast thing.’ And that’s kind of what Roger has always done. As the market changes, he’s been able to adjust to it quicker than most people.”

DVD cover for Piranhaconda (2012).

Production stills from Attack of the 50 Foot Cheerleader (2012), directed by Kevin O’Neill. Thirty-seven years after his blink-and-you’ll-miss-it appearance in Death Race 2000, John Landis drops by for a cameo as a college professor. He probably could have directed the picture with one eye closed. A pair of pom-pom girls goes for the jugular.

JOHN LANDIS: “I don’t think people realize what an accomplishment it is to get a movie made at all these days. And one of the things that I love about Roger is he’s still making movies. It’s in his blood. He and Julie, they’re still making movies. He recently asked me to be in a movie called Attack of the 50 Foot Cheerleader. They made it for a dollar sixty, and I didn’t get paid, but how could I possibly say no?”

JOE DANTE: “To make lower-budget pictures these days is really more of a challenge than it ever was, because in the seventies there was the novelty of the fact that we hadn’t seen all these movies with chicks and blood and all that stuff. Now we’ve seen just about everything. We’ve got the fucking Human Centipede, so there’s not much further to go. And since a lot of the impact of exploitation films relies on shock and pushing the envelope, it’s just a question of what’s left to shock people. Roger’s seen the business go through a staggering amount of changes over the years, but he’s still in the game. No one knows right now exactly what the next thing is, or what the next delivery system is, or how the films are gonna be marketed, or to whom they’re gonna be marketed, and how they’re gonna play, and whether they’re gonna be projected on the inside of your eyeballs someday, or what. And so there’s a tremendous amount of uncertainty in Hollywood now about what’s going on, and I think that’s reflected in the fact that all the movies are safe bets. There’s a lot of fear in the executive suites today, and I think it’s a fear of the future. They just don’t know what it’s gonna be.”

LLOYD KAUFMAN (founder of Troma Films): “Right now, business couldn’t suck more. I speak to Roger quite a bit, and, you know, we call each other and sort of compare notes. One of the advantages to being a small studio is that you can move fast. Whatever the future ends up being, I would bet on Roger. He’s always right. And unlike ninety-nine percent of the movie industry, he’s not a creep. He’s a real person. He and Julie are decent people. And he’s smart enough not to be too bitter about how the business has changed. He loves it too much. He genuinely loves movies, and I think that’s what propels him. Everybody says, ‘Oh, Roger, he’s parsimonious.’ You know, that’s condescending. He’s an artist. I’ve spent a lot of time with him, and there’s no reason for him to work, but I’m convinced that he loves making movies too much to give them up.”

U.S. posters for The Fast and the Furious (2001), directed by Rob Cohen, and Death Race (2008), directed by Paul W. S. Anderson. Corman’s high-concept ideas and knack for attention-grabbing titles are catnip for today’s studio executives.

ANDREW STEVENS: “Why does Roger still do it? He’s compelled to. It’s why salmon swim upstream to spawn and lemmings jump into the sea. I think Roger in his eighties is revered and celebrated. No one gets credit, but the independents are the free farm clubs for the majors, and we groom the talent that goes on to support the major studios, and yet we’re hounded and vilified by the unions and dismissed by the majors. But if we didn’t exist, they would have to find an alternate source to groom and train people. Every major league ball club has farm teams, and they groom and train their up-and-coming people for the major leagues. A lot of people say if you stop working you get old and you die. And I believe Roger will work up until he physically can’t because it’s what drives him. He cares very deeply about things that one would think at this point in his life would be frivolities. There was a scene in The Terror Within that got a laugh in the screening, and he made me cut the moment out. I thought it was a great moment. But he felt that people were laughing at the film, not with it. And he doesn’t want to be laughed at.”

FRANCES DOEL: “I think he keeps making movies because there’s an aspect to it that’s an intellectual challenge. ‘Intellectual’ may be too fancy a word, but the pop he got from the Syfy channel from those monster movies like Dinocroc and Supergator, I think he got a lot of satisfaction out of always finding a way to keep going in a time when there’s 3-D and expensive effects and I think he will keep on going. But he has said that this looks to him like the first time when he really can’t see that there’s an audience for low-budget pictures. I think he can’t yet see what might change or what opportunities there might be. I think he believes that the whole movie business is turning upside down and is never going to be what it was.”

Frame grab from Sharktopus (2010), directed by Declan O’Brien. Eric Roberts plays God and pays for his hubris in one of Corman’s SyFy originals.

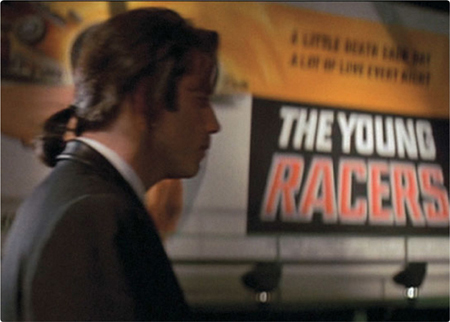

Frame grab from Pulp Fiction (1994), directed by Quentin Tarantino. A nod from one movie-mad director to another, as John Travolta’s hit man Vincent Vega struts past a poster for Corman’s 1963 film The Young Racers at Jack Rabbit Slim’s.

Dinocroc vs. Supergator 2010

In the early years of the twenty-first century, the question of how to stay relevant—and profitable—wasn’t new to Roger Corman. He’d been wrestling for decades with the changing winds of the marketplace and evolving methods of distribution. At the dawn of the VHS revolution, he was one of the first producers to recognize and tap into the new technology, funneling made-for-tape cheapies into mom-and-pop video stores across the land. When the spectrum of pay-cable channels expanded, he fed their hungry maw with his enormous back catalogue of titles. And when DVD took off, he was quick to seize the moment again. Roger Corman is Hollywood’s most tenacious survivor.

In the mid-2000s, Corman found a new partner in the Syfy network. Just as he had in the fifties, Syfy (formerly the Sci-Fi Channel) tapped into an underserved audience, where low-budget monster mash-up movies were spun into ratings gold. The formula was simple enough: Grab an underemployed star (David Carradine, for example), plop them in an exotic setting with palm trees (Hawaii is nice this time of year), stir in a couple of computer-generated beasties with a nature’s revenge subplot, and voilà … you have a “Syfy Original.” Corman’s new breed of B movies featured monsters with names like Sharktopus and Piranhaconda. They were right in his wheelhouse. And he could crank them out quickly, cheaply, and in bulk—just as he had fifty years earlier with AIP.

Frame grabs from Dinocroc vs. Supergator (2010).

One of the best of the new breed was 2010’s Dinocroc vs. Supergator, directed by Corman stalwart Jim Wynorski (working under the pseudonym Jay Andrews). Carradine, in one of his last roles, plays a lizard-like biotech tycoon named Drake—an amoral scoundrel who has been conducting secret lab experiments on super-size reptiles in the hopes of using their DNA to help create a breed of human super-soldiers. His attempt to play God goes awry when his T. rex–sized Dinocroc and Supergator escape from his tropical facility and tear his staff of chesty white-lab-coated scientists limb from limb. In the meantime, we’re introduced to the film’s roster of heroes and heroines lining up for the reptilian luau. There’s a beautiful blonde fish and game officer (Amy Rasimus), an undercover government agent in a garish Tommy Bahama shirt (Corey Landis), and The Cajun (Rib Hillis), a Quint-like swamp hunter who looks more like a stubble-faced refugee from a nineties soft-core erotic thriller.

Frame grabs from Dinocroc vs. Supergator (2010). Which one’s the Dinocroc and which one’s the Supergator?

Prancing in and out of the frame between exposition points are an array of bikini-clad babes who strip down to frolic in Kauai’s edenic waterfalls before being turned into bloody dino-chum by the Harryhausenesque CGI Dinocroc and Supergator (it’s never really clear which is which). The most interesting moment in the movie has nothing to do with cleavage or carnage. It occurs when a group of fanny pack–wearing tourists visits a run-down resort on the island and they’re informed by their guide that it was used as a location on “the classic film She Gods of Shark Reef.” It’s a nice, winking inside joke referencing Corman’s B-movie past. Which is exactly what the entire film is. Dinocroc vs. Supergator is one of Corman’s fifties monster movies reverse-engineered for a generation of millennial, Comic Con fanboys weaned on self-referential irony. Corman understands the rules of the new game—that meaningful subtext was sacrificed at the altar of reality-TV sensationalism a long time ago. And even after all these years, he’s a shrewd enough businessman to give the audience what they want.

JOHN LANDIS: “Roger is a very smart guy. And what is true is that you always need the filmmakers. It doesn’t matter what the delivery system is. You still need someone to actually create the images being watched. And basic filmmaking has not changed in a hundred years. The juxtaposition of images, moving pictures, to tell a story—it’s called montage, and film language itself is the same as it was in 1904. Other things have changed, color, sound, technology, but motion-picture storytelling hasn’t changed at all. Roger is a smart enough guy that he will always figure out a way to make a buck in this business. By the way, did you ever see Joe Dante’s film, The Howling? There is a wonderful scene where someone has to desperately use the telephone, and they run up to a phone booth but there is a man in there. So they’re like, ‘Oh, God, hurry up, hurry up.’ And it’s Roger Corman in the phone booth. Finally he finishes his call, hangs up, and the person is about to go in when Roger goes back into the booth to check and see if the dime was returned.”

Frame grab from The Howling (1981), directed by Joe Dante. Roger Corman makes a cameo in his old protégé’s film, where the notoriously tight-fisted producer checks a pay phone change slot to see if his dime was returned.

JOE DANTE: “There are two kinds of people who work for Roger: the people who went on to something else and are grateful about it, and the people who didn’t go anywhere because they felt that the work was beneath them. They didn’t try to make the best women-in-cages picture they could possibly make. They would say, ‘This is all junk; I’m saving myself for my magnum opus.’ Well, you know what, they never got to make a magnum opus. I think that’s the guiding principle behind everybody who’s come out of that place. You give your all to every project no matter what it is. You have to be consumed with film to make films. You have to love it. And Roger loves it. The funny thing is, when we have these reunion events for everyone who started out working for Roger, people come back—people who were paid less than minimum wage by Roger—and they are all so grateful to be in the business at all and to have gone through the Corman School. They have nothing but fondness for him, no matter what issues you had with him at the time—and you could have many issues. They were your salad days. It was something that we didn’t really appreciate until we went on to work on major budget pictures, where there are many more restrictions and many reasons why you can’t do this or can’t do that. With Roger, as long as you gave him what he wanted and what he needed to sell the movie, you could make the movie any way you wanted as long as it wasn’t upside down or in black-and-white when he said he wanted it in color. When you look back, there was a tremendous amount of self-expression going on within the confines of these movies—and camaraderie, of course. You’d bitch about the hours and the pay and all that stuff, but the fact is you knew that you were on the way to something.”

RON HOWARD: “It’s a little like Branch Rickey with Jackie Robinson. Roger ushered in an entire generation of people who felt like outsiders. He had a point of view about how it could be good business. And you can’t tell me that on some level he didn’t want to give people an opportunity. He wanted to break down those barriers; he thought those were silly. He made a lot of money doing it. And everyone understood that. And he’s still doing it.”

Publicity photo from the set of The Silence of the Lambs (1991), directed by Jonathan Demme. Jonathan Demme gives his old Caged Heat producer a cameo as FBI director Hayden Burke in The Silence of the Lambs.

Photo of Roger Corman, circa 1996. Corman poses with what would have been a week’s output as a director back in the fifties. © MR Photo/Corbis Outline

JONATHAN DEMME: “Roger doesn’t talk about it, but I’m pretty sure he must feel good to have given people an opportunity and more often than not see them fulfill his hopes that they do a good job. I certainly feel that way myself now. I’m an older filmmaker, and I’ve worked with a lot of younger people, and I get it. It’s a terrific thing he did! It’s incredible! Over the years I’ve become very fond of Roger as a person. I have tremendous respect for him in every way. He’s a big-hearted guy who tries to conceal it as much as possible. I coaxed him to play a part in Rachel Getting Married. And there was a shot that got cut of him filming the couple at the wedding, and it’s very emblematic of him that in the shot, he’s got a big grin on his face. He just loves shooting. We all want to be independent filmmakers. But no one’s ever been as remotely independent as Roger.”

JONATHAN KAPLAN: “Roger fulfilled a need in Hollywood that’s not being fulfilled anymore, which is the post-graduate school of filmmaking. He taught people … we all know who. Ron Howard, Bogdanovich, Coppola, Scorsese. But I also think that deep down he’d like to be remembered for his own films, too.”

GALE ANNE HURD: “Around 2000, all of the Corman alumni lobbied the Motion Picture Academy for Roger to receive an Oscar. He was supported by Jack Nicholson and Jonathan Demme and Martin Scorsese and Francis Coppola and Jim Cameron and Ron Howard, all the Corman grads. Everyone pulled together to make sure it happened.”

MARTIN SCORSESE: “The first time we tried to get him an Oscar was in 2000. And then a couple of times after that. To me, it just seemed really important, not just for his excellent filmmaking but his embrace of new genres coming out of Hollywood. And also for the Roger Corman University—all of the talent he gave a chance. He could tell it was in you. After that, you were on your own. Because if you had anything in you, he would say, you’d move on after one or two films. He was just interested in getting that one moment. He was taking advantage of you, but you were also taking advantage of him and the opportunity.”

Jonathan Demme presenting an Honorary Academy Award to Roger Corman in 2009. After beating Hollywood at its own game for decades, Corman is finally given entrance to the Club.

Roger Corman surrounded by graduates of the University of Corman on Oscar night, including Ron Howard, Jack Nicholson, Peter Bogdanovich, and Jonathan Demme.

BRUCE DERN: “I think it took so long because he had the reputation that he made B movies, drive-in movies, bad movies, you know? What does it matter that they’re in drive-ins? Roger made movies in every genre you could imagine. I remember being on a movie recently where some of the people mutinied because the salmon was bad. And when they came back from their little mutiny, I gave them a lecture that they’ll never forget. I just said, ‘Let me tell you something, you should be fucking thrilled you’re here. You have an opportunity to make a movie. That’s why you got into this business. I don’t care whether you’re in craft service, or you’re a cinematographer, or you’re the star of the movie. We should be excited to have an opportunity to be here, where somebody else has given us money to live our dreams. All of you just ought to shape up, and pull your oar.’ Movies are teamwork. That’s the Roger Corman credo. He gave us all the feeling that it was a privilege. And if we didn’t think so, we shouldn’t be in the business.”

FRANCES DOEL: “I think when Roger was finally given the honorary Oscar in 2009, it meant one hell of a lot to him. And I think he was surprised, quite frankly. Because he never made or, with the exception of The Intruder, set out to make films that would get him acclaim of his peers. I think he would have thought of the Academy as mainstream—they’re the world that he’s always tried to outwit. So I think there was a degree of surprise. But I know it was a welcome surprise.”

JOE DANTE: “I think getting the Oscar meant the world to Roger. I can’t imagine a greater indication for a guy who was consistently relegated to the lower leagues and not considered one of Hollywood’s swells because of the kind of stuff he made. But of course the stuff he made is probably what shaped the whole culture. If everybody that ever went through the Corman School was left behind, or just disappeared so there was nothing left but their clothes, this business would not function. It would be impossible. Everything leads back to Roger.”

TOM SHERAK (former president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences): “The best part of the job is making calls like the one I made to Roger telling him he was getting an Oscar. He sounded like a kid in a candy store. He said, ‘You’re kidding? You’re kidding?’ I said, ‘No, I’m not, Mr. Corman.’ And he said, ‘Tom, I can’t thank the Academy enough.’ I think he almost cried … and I think I almost cried. Look, excellence comes in many different ways. Not everyone has to be David Lean. Roger made some great movies and discovered more talent than any filmmaker than I can think of. It’s funny, after the awards ceremony, I caught The Godfather Part II on TV, and there was Roger acting in the film. He was really good! He could have been an actor. Good-looking guy.”

JOHN LANDIS: “Hitchcock said the greatest thing to me about the Oscars—and this is absolutely true. He said, ‘The Academy Awards are trivial bullshit. Unless, of course, you’re nominated.’ It’s terrific, and it’s true. I wrote a letter to the Academy on Roger’s behalf. And if you talk to Ron Howard, or Joe Dante, or Allan Arkush, or Francis Coppola, or Peter Bogdanovich, or Jonathan Demme, or Marty Scorsese, or Jim Cameron, none of them will say, ‘What an asshole.’ That’s unheard of in this business. Working for him was an extraordinary moment in their lives.”

GENE CORMAN: “Roger should have gotten the Thalberg Award for being the most important motivator of motion pictures in our time years ago. Hollywood wouldn’t be Hollywood today without my brother. I guess the wiser men of the Academy thought his reputation isn’t double-A. It’s hard for people to understand that someone can be as tremendously successful and talented as Roger. That night, he had a table with Jack Nicholson and Jonathan Demme and Ron Howard, and you have never heard pounding on tables and cheering like he got when he went up to accept his award.”

Roger Corman basks in Oscar’s afterglow with fellow honorees Lauren Bacall and cinematographer Gordon Willis. © Chris Pizzello/AP/Corbis

ROGER CORMAN (in his Oscar acceptance speech): “Needless to say, I’m delighted to accept this Oscar personally. But I’d also like to accept it on behalf of my wife, Julie, who’s been my producing partner for many years. I think that to succeed in this world, you have to take chances. I believe the finest films being done today are done by original, innovative filmmakers who have the courage to take a chance and to gamble. So I say to you, ‘Keep gambling, keep taking chances.’ Thank you.”