A few years ago, I climbed Drift Peak near Leadville, Colorado, on Presidents’ Day with my friend Aaron and my friend Lee. Lee had started up the peak a couple times before in the winter, but bailed for different reasons. He had promised that if we made it to the summit with him on what would be his first successful winter ascent of the peak, he’d tell me the story of how the mountain had “almost killed” him. I expected, of course, another story like the time he was climbing the northwest face of Torreys Peak by himself in the winter and a rock came screaming down the mountain, slamming into his foot and breaking three bones. He had to glissade down 800 feet, then use his ski poles as crutches to hike out the remaining 2.5 miles to his truck, and then drive home to Littleton, where he almost drove through the back wall of his garage because he couldn’t get his smashed foot to engage the clutch in time.

The Drift Peak story wasn’t quite like that. As we descended the snowy ridge, I was quietly satisfied I had made the summit without throwing up, while Lee had the energy of the Kool-Aid Man. He darted past Aaron and me, yelling, “Gather ’round, Girl Scouts. It’s time for a story!”

There he was, his story began, not too far away from where we were sitting, by himself on a cold December day in 2000. He was planning on climbing Fletcher Mountain, a half mile further up past the summit of Drift Peak. He trudged up the snowy ridge, and at the point where the final summit slopes began, he came up on a notch in the ridge. He’d have to climb down a 40-foot slope, then back up a 60-foot slope, to regain the ridge. The second slope was high angle and looked ripe for an avalanche.

Instead, Lee turned around to go home and live to climb another day. The ridge, after all, is colloquially known as “Villa Ridge,” named after a man killed by an avalanche on it.

Lee made his way back down the ridge and stopped on top of a large snow dome to eat lunch. It was eleven o’clock in the morning. He jammed the spike of his ice axe into the hard snow and tied his pack to it, anchoring it so it wouldn’t slide away. He opened his pack and pulled from it his absolute favorite mountain lunch: A ham-and-cheese sandwich on whole wheat, with mayonnaise and mustard.

This, Girl Scouts, is the “No shit, there I was” part of the story.

Munching on his sandwich, enjoying the view to the south of the Sawatch Range, Lee stopped breathing. He tried to cough, but nothing. His airway was completely blocked by a piece of sandwich. He hacked. Nothing. After ten or so seconds of desperately trying to draw in some thin, 12,900-foot-high air, he began to see a gray frame at the very edge of his vision. He realized he had wasted a lot of time.

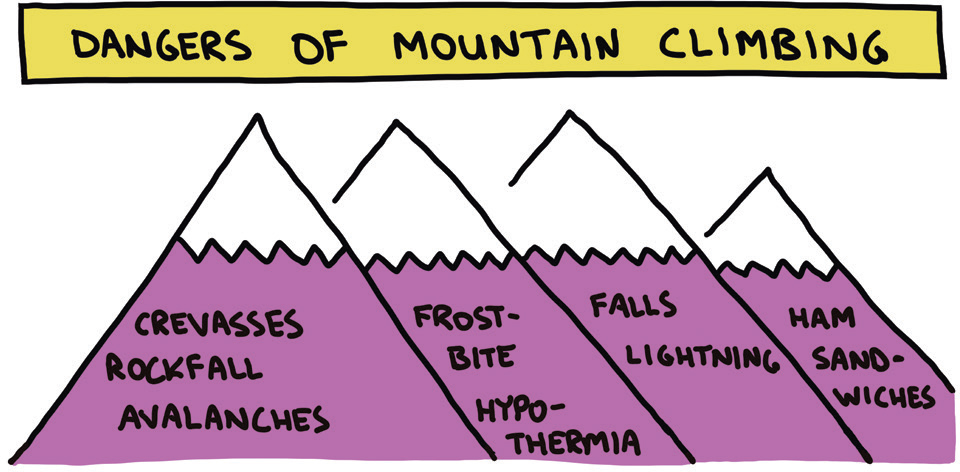

He had survived thirty-five years of pushing his limits in the big hills, including hundreds of pitches of roped climbing, that falling rock on Torreys Peak, the occasional incompetent partner, stuck ropes, Rocky Mountain thunderstorms, and more, and he was about to be killed by a goddamn ham sandwich. His story in next year’s Accidents in North American Mountaineering would be hard to frame as “heroic.”

In 1974, American physician Henry J. Heimlich popularized a series of abdominal thrusts that came to be known as “The Heimlich Maneuver,” a technique that has saved the lives of many humans who neglect to chew their food completely. The light bulb went on in Lee’s oxygen-deprived brain and he remembered the self-Heimlich technique, in which a choking person can Heimlich themselves by leaning over, say, the back of a restaurant chair and pushing it into their diaphragm.

There are no chairs on the northwest ridge of Drift Peak.

But what about wedging the spike of his ice axe against a rock and driving the head of it against his abdomen? Lee looked around. Nothing but snow, which would just give way under his weight. He would have to glissade down the ridge to a talus field 40 feet away to find a large rock: if he could make it in time.

The gray circle around his vision grew larger, and the tunnel of beautiful Colorado mountain scenery shrank. Sixty percent vision now. He frantically fiddled with the knot attaching his ice axe to his pack. Come on, come on, come on. It came free. His pack shot down the slope in front of him. Still, no air.

Lee ripped the ice axe out of the snow and pushed himself into a buttslide down the slope. He planted the head of his ice axe underneath his ribcage, adze pointing right, pick pointing left. His chest sucked itself into a knot, starving for oxygen.

He picked up speed, lifting his feet in the air so his crampon points didn’t catch. His vision tunneled down to 25 percent. At the end of that tunnel was a rock shaped like the state of Tennessee, pointing straight up in the air, flat side facing Lee.

His last thought was, “I’m aiming for Memphis.” Just before slamming into the rock, his vision went black. He passed out. Well, he assumes he passed out, because he doesn’t remember hitting anything.

He woke up on his back, sucking in air in big gulps, holding a round ball of ham, cheese, mayo, mustard, and whole wheat bread in his mouth. He spat it out.

Everything hurt: stomach, chest, back, shoulders—his hair hurt. The Tennessee-shaped rock sat a foot and a half behind his head. The Rocky Mountain Self-Heimlich had worked. Near as he could tell, the piece of sandwich had dislodged when his ice axe hit rock and the head of the ice axe compressed his diaphragm.

Or, the ham bolus popped out of his throat when he flopped onto his back after doing a full somersault over the rock. While completely unconscious.

Either way, two thoughts popped into his head: “I could have died” and, “but I didn’t.”

Sitting at the same spot on the ridge eight years later with Aaron and me, Lee closed his story, saying, “And I’ve never told anybody that story till now, because if my wife had found out, she never would have let me go climbing again.”

To which I replied, “Or eat ham sandwiches by yourself.” If not for the unfortunate but amicable dissolution of Lee’s marriage a few years ago, he may have taken that story to the grave—in his journal for the day, he recorded it simply as “an interesting day.”