In January 2015, two guys finished climbing an astronomically difficult 3,000-foot route on El Capitan as the world kept up via seemingly every mainstream news source: CNN, the New York Times, the Washington Post, Sports Illustrated, and all of the major news networks. Climbers and non-climbers followed the final pitches of Kevin Jorgeson and Tommy Caldwell’s nineteen-day efforts on a live video feed, which was simultaneously kind of boring (as watching rock climbing from a distance usually is) and absolutely enthralling.

When Jorgeson joined Caldwell at the final anchor at the top of the final pitch, two tired guys hugged at the end of a monumental, multi-year effort, many of us rejoiced, and social media feeds blew up with everyone’s own version of “[insert exclamatory phrase here] Dawn Wall!”

Throughout the two weeks of media coverage, a few people seemed to not get the whole thing, calling the climbers adrenaline junkies, or accusing them of doing it for fame or attention or money, or saying that they should have spent their time doing something that would benefit humanity. I dug into the comments section on a New York Times story on the climb and found a gold mine of vitriol. I cringed, laughed, and collected it and put it all together in an Adventure Journal post.

It’s one thing to not understand climbing—it turns out it’s incredibly complicated to explain why the route, and the climb, was such a big deal. If you don’t climb, you might not get that the sport of climbing is statistically relatively safe (compared to driving on the freeway), relatively not harmful to the park (compared to the impact of thousands of park visitors every year), and that there are differences between aid climbing, free climbing, and free soloing. Likewise, many of us don’t understand the technicalities rules of lots of Olympic sports, or stock car racing, or the categories at the Oscars, and the idea of using or not using ropes in climbing was definitely lost on many people.

But there were also dozens of indignant comments from people who seemed to think the whole thing was a giant waste of time:

Robert Frodeman, Denton, TX

Strikes me as a dumb way to spend one’s time. Dangerous, and for what purpose? A thrill. One should devote such considerable energies to something more constructive.

KittyKitty7555, New Jersey

Am I the only one who thinks that the energy directed into this very difficult climb could have been better directed elsewhere? Yes, I’m sure it was really hard, but what was produced except self promotion?

Sometimes we complain that the news is all negative: if-it-bleeds-it-leads, “Man Shot,” “Baby Drowns,” “Car Accident Kills Six,” “Hostage Beheaded,” “War Continues Even If We Don’t Call It War.” And then a story that’s hard to see as negative (“Two Men Climb Giant Difficult Rock Face, No One Dies, Some Fingertip Skin Damaged”) takes over some headlines for a while and people flock to the internet to take a shit on it, saying these two guys could have done something different with their time.

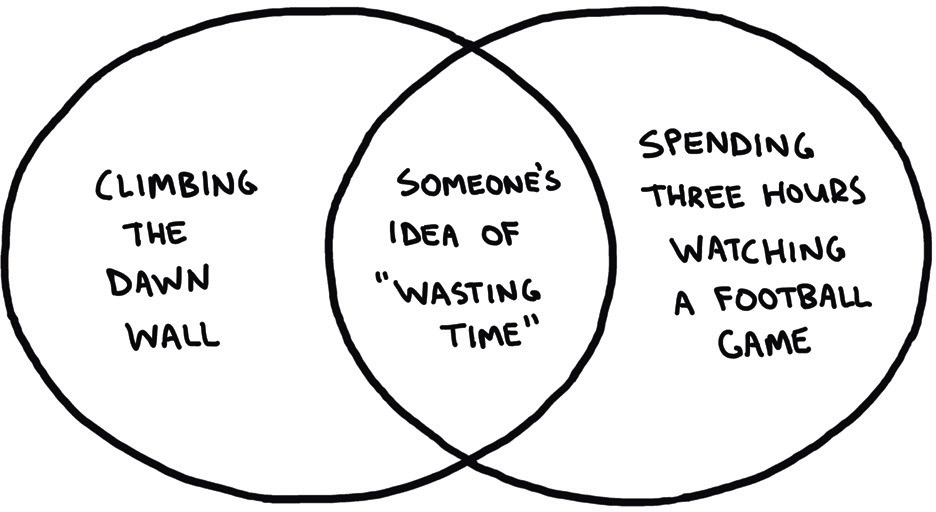

Well, ok, what’s an acceptable way to spend your time, instead of climbing the Dawn Wall? Would it make us feel better to see Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson sitting next to us in traffic on Monday morning? Should they have sat down and watched all the seasons of Game of Thrones consecutively? Spent some days at one of those drink-wine-while-you-learn-to-paint classes? Done their part to contribute to the three billion hours we spend playing video games each week? Maybe they could have replied to all the internet comments concerning their climb?

When we see someone doing something we deem foolish, we have a tendency to say something like “they have too much time on their hands.” And we forget that we’re privileged to have any spare time on our hands at all, something that was an unforeseeable luxury not too many generations ago—when we spent all of our time trying to survive—and something that doesn’t exist at all for the often-invisible people sometimes halfway around the world who pick the produce we eat or make the clothes we wear.

The advance of civilization has given people the opportunity to have spare time, and with that spare time we have found ways to express ourselves. Art, whether it’s Shakespeare or Picasso or Illmatic, or The Tonight Show With Jimmy Fallon, is created by people with spare time, and consumed by a much larger amount of people with spare time. Some of it we embrace, some of it we discard, and all of it, in the grand scheme of things, is arguably folly.

Charlie Todd, the founder of the prank collective Improv Everywhere, gave a TED Talk on “The Shared Experience of Absurdity” in 2011, and addressed the criticism he’d heard about how he chose to spend his spare time:

One of the most common criticisms I see of Improv Everywhere left anonymously on YouTube comments is: ‘These people have too much time on their hands.’ And you know, not everybody’s going to like everything you do, and I’ve certainly developed a thick skin thanks to internet comments, but that one’s always bothered me, because we don’t have too much time on our hands. The participants at Improv Everywhere events have just as much leisure time as any other New Yorkers, they just occasionally choose to spend it in an unusual way.

You know, every Saturday and Sunday, hundreds of thousands of people each fall gather in football stadiums to watch games. And I’ve never seen anybody comment, looking at a football game, saying, ‘All those people in the stands, they have too much time on their hands.’ And of course they don’t. It’s a perfectly wonderful way to spent a weekend afternoon, watching a football game in a stadium. But I think it’s also a perfectly valid way to spend an afternoon freezing in place with 200 people in the Grand Central Terminal or dressing up like a Ghostbuster and running through the New York Public Library. . . .

As kids, we’re taught to play. And we’re never given a reason why we should play. It’s just acceptable that play is a good thing. . . . I think, as adults, we need to learn that there’s no right or wrong way to play.

In our early years, like Charlie Todd says, we all find different ways to have fun: playground football, drama club, being the class clown, building elaborate models out of toothpicks, rock climbing, writing stories. Some people find ways to turn “play” into a job later, but not all of us do, and some of us consider ourselves lucky enough to hang onto playing well into adulthood as something we can do for a few hours a week or a month.

In an interview with the New York Times at the top of El Cap, Jorgeson said, “I hope it inspires people to find their own Dawn Wall.” I like to think he means a couple things with that: that we all should have and hold onto big dreams, and we should never stop playing, whether or not everyone agrees that it’s making the world a better place.