Just east of Green River, Utah, on Interstate 70, I looked over from the passenger seat to see the car’s gas gauge hovering around a quarter full. I mentally catalogued the distance and number of gas stations between us and the Hot Tomato in Fruita, Colorado, and could only remember one in those 90 miles.

“Maybe we should stop and get some gas,” I said to my friend Forest.

“I think we’re good, don’t you?” Forest replied.

Forest is a photographer, and we’ve known each other for almost six years. We’ve spent dozens of days together, collaborating on outdoor magazine articles, adventure films, and now a book project—and we approach things from almost complete opposite ideologies. You might say I’m a bit more of a planner, and he flies by the seat of his pants. I like to say that the world takes care of Forest, but I don’t trust the world to take care of me. I eliminate as many variables as possible prior to doing something—he more or less lets the variables fall where they may.

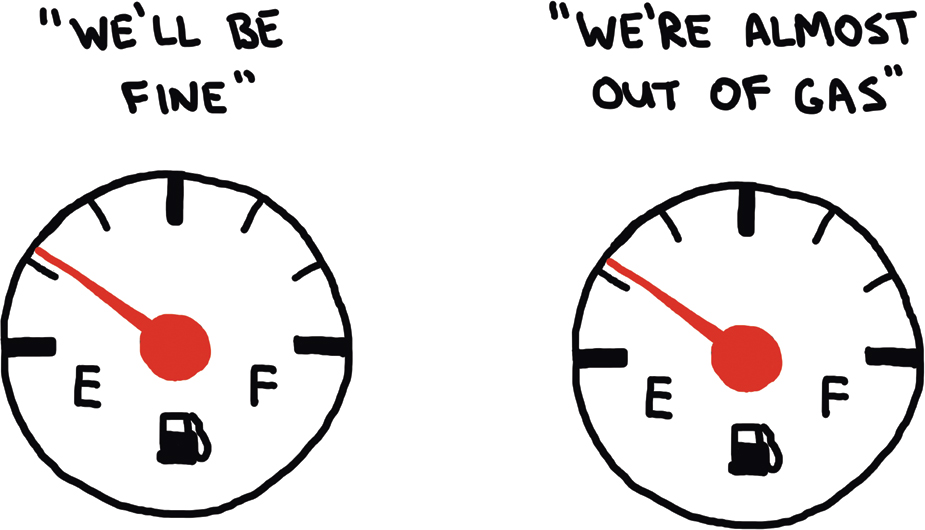

And there we were last Thursday, in eastern Utah, both looking at the gas gauge but seeing completely different things. We discussed the gas tank capacity of my car (16.9 gallons), the average miles per gallon the car got on the highway (up to 27 miles per gallon), and how far we had to go to the next known gas station (about 80 miles). Mathematically, we were right on that line between We’ll Be Fine vs. We’re Going to Run Out of Gas. Which is a classic “There are two types of people in this world” debate.

I asked Forest, “Have you ever run out of gas?”

He laughed. “Several times.”

“I never have,” I said.

“One of those times I ran out of gas,” Forest said, “I got out of the car and there was a gas can sitting off to the side of the road, and I had pulled over just down the hill from a gas station. So I grabbed the gas can, jogged up to the gas station, filled it up, and the whole thing only cost me about fifteen minutes.”

“That is the most Forest Woodward story of all time,” I said.

“I was on my way to the airport, too.” Of course he was.

We started talking about the differences in the ways we view the world. I book flights weeks in advance. Forest books flights a couple days in advance. I have 11 unread emails in my inbox right now, and he has more than 2,500 unread emails in his inbox. I can go years without losing a water bottle or travel mug, and, well, Forest can go weeks, or days. Two days prior to our drive through Utah, we had run 37 miles across Zion National Park, and Forest had worn trail running shoes with almost no tread on them, with three-inch rips in each instep, and with laces barely hanging onto enough of the shoe to stay on his feet. And his water bottles were leaking.

Despite, or maybe because of, this difference in thinking, this massive chasm between our ideas of How To Do Things, we enjoy each other’s company and (in my opinion) work well together on creative projects. Ten years ago, even being in close proximity to his laissez-faire planning would have driven me nuts, but nowadays I try to watch him, remind myself to relax, and not try to control everything. Because it always seems to work out for Forest. Of course, he notes an asterisk to that statement, that even though it always works out, it can sometimes be expensive, and he has definitely missed a few emails that might have meant the successful sale of a photo or two.

But, it always works out for me, too—no matter how much I try to control things, or just let them go—even if the way it works out isn’t how I imagined it. Flights get delayed, it rains when I don’t want it to, bikes get flat tires, avalanche conditions are terrible sometimes, packages get lost in shipping, and in the end, our story isn’t something any of us are in control of, whether we think we are or not. The one thing Forest and I agree on is that whether you plan or don’t plan, you can’t get angry and try to place blame on someone else when things don’t work out. Because whether you believe you can control things or you don’t worry at all about trying to control things, shit happens. And when it does, nobody wants to be that jerk with a vein popping out of their forehead as they scream at an airline employee about how important they are.

Last year, I read an essay titled “Do You Want to Be Known for Your Writing, or for Your Swift Email Responses?” and I realized, shit, I actually would love to focus on my creative work more than I focus on answering email promptly. I’m trying, but it’s a battle to even pretend to ignore my inbox. Or gas gauge.

We pulled off at exit 15 for Loma, Colorado, and both sighed, Forest more than me, as I announced that we still had 1.3 miles, mostly downhill, to the Conoco station north of I-70. We made it, filled the car up with gas, and were not late for the film festival we were driving to that evening. It worked out. The world continues to take care of Forest, I continue to not totally trust the world to take care of me. But when we’re in the same car with a quarter-tank of gas, as a friend once told me, “One way or another, it’ll work itself out.”