43.

OUT OF THE CANYON

Strong convictions are the secret of surviving deprivation; your spirit can be full even when your stomach is empty.

—Nelson Mandela

We are just going to hike until lunch.” My sister Peggy’s alto voice was certain and persuasive, as usual. “I’ve been to the oasis before and it’s a really beautiful place. The staff from the lodge is going to bring our picnic there so all we have to carry is our water and a few snacks.”

The year was 2008. We were camped by the Fish River, below the edge of what’s called the Grand Canyon of Namibia. Peggy and a few other investors had recently acquired a large tract of land where they were building an eco-lodge. They had found multiple petroglyphs near the oasis and she wanted us to see them. My brother Richard and his new wife, Nancy, Peggy, Paul, and I had hiked to the bottom of the canyon the day before, over many loose rocks, with Peggy’s ranch manager, Ian. Our tents had been set up ahead of time, next to the river, and we had enjoyed a relaxing evening around the campfire.

Today we were on a tight schedule for a very exciting reason. Today we would soon meet Nelson Mandela. Peggy had known him for several years, through her work with the antiapartheid movement. She arranged for us to fly in a charter plane from the top of the canyon to Johannesburg to have dinner with him. Nancy, Richard, Paul, and I had been looking forward to this for months. Afterward we would go on safari to Botswana with my dad; I hadn’t been to Botswana since my first job out of college.

I was looking forward to again seeing the Savuti wilderness where I had camped for three weeks in 1974, but I was even more excited at the prospect of meeting the great leader of South Africa. I was counting the hours.

“Are you sure we will be able to find our way to the oasis in time for lunch?” I asked cautiously, remembering other adventures with her that had required twice the length of time and resulted in more danger than anticipated.

“I wouldn’t be suggesting it unless I was,” she answered testily. Persistence had been her ally in getting her way. It had also helped her found a not-for-profit organization, Synergos, in 1986, to bridge grassroots, political, and business leaders from around the world. Her mission was clear: to forge new ways to overcome poverty. All I wanted was a sure way to reach the oasis.

Peggy does everything on a large scale. From the time I was a teenager, I watched our dad take her under his wing. It seemed he wanted her to carry out his work in the world. She’s well suited to the task. I admire the way she navigates foreign countries, people, and ideas, but I haven’t always trusted her when it comes to safety. As a child she rode the fastest horses available and encouraged me to voluntarily fall off our donkey so I could learn to relax when the real fall happened. I never did quite understand her logic. Now we were with her in one of the driest and most remote places I had ever seen. I did not know then that hiking in the Fish River Canyon is recommended only for the brave and hardy who have passed a medical examination.

I looked up from where we were standing to the canyon rim, near where I imagined the oasis sat, a fifteen-hundred-foot vertical cliff of sandstone and shale. I did not relish the idea of climbing up there or possibly falling. Peggy explained, “We’ll be hiking along the river until we reach the canyon that leads to the oasis. I’m sure there’s an easy way in.” Her eyes were on fire with excitement. The truck, which had come down to our campsite to collect our tents, food, and other gear, left in a trail of dust up the rough dirt road.

I packed my small first-aid kit in my backpack, along with a few extra clothes, just in case it didn’t turn out the way she imagined. I had been on “short hikes” with her in the past that ended up being over twenty miles. We six picked up our daypacks and water bottles and started off along the river.

The sun warmed quickly, from forty degrees at dawn to over ninety degrees. Richard and I decided to take a swim. We found a flat rock, stripped down, and went in. Richard did not look carefully before diving and cut his elbow almost to the bone. My first-aid kit was already coming in handy. I placed one of the butterfly Band-Aids tightly across the cut and we continued.

A tawny eagle circled above us. I wondered whether this was an auspicious sign, but I kept my thoughts to myself and walked close to Paul. Better not to be an alarmist.

We passed the base of the first and second canyon. Peggy and Ian discussed whether the third was it. “I’m sure it’s not,” said Peggy. Ian admitted he had never been to the oasis before. Why hadn’t he told her earlier, and why hadn’t she asked? Peggy confessed, “Well, I’ve only hiked down from the oasis to the river, not up. I thought you knew the way.” Had I known this before we left, I would definitely have said no. But we were committed now and the next canyon was just around the bend. Paul and I talked in low voices about when we should turn back. We decided to defer to my doctor brother.

Five canyons and five hours later, Richard and Nancy, who had stayed quite a distance in the rear, caught up to us. Richard took a stand.

“Peg, this is not working for Nancy or me. It is now almost two o’clock and even if the next canyon is the right one, it will be a difficult hike up, and we have probably missed our chance to meet Nelson Mandela. We’re almost out of water. We are playing with death. I can’t speak for the rest of you, but we are not going any farther.”

I was deeply relieved. Somehow, I had worried I would not be listened to if I spoke first, but now that Richard had voiced his concern, Paul and I echoed him. He was the doctor, after all. He was still taking Gleevec, the medicine for his chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML), from which he was now considered almost symptom-free, but the medicine made him prone to severe cramps.

After a weak protest from Peggy, she agreed to return with us to our campsite and wait until we were found. Ian ran ahead to see if he could intersect the truck, whose trail of dust we had seen speeding along the rough road on the canyon wall above us. By now they were searching for us.

Our water was almost gone. Richard volunteered to be the first to drink from the river and let us have the rest of his water, as he would need antibiotics anyway for the cut in his elbow. We decided to walk straight back, crossing the river where it bowed, to get to the campsite earlier. As it was, we were not sure if we would make it by nightfall.

A small plane circled in the distance. We were sure this was the charter we were supposed to be on and that it must be looking for us. We shouted and waved our arms, but after several passes it disappeared. My heart sank. We were hungry, thirsty, and worried. Dusk was descending fast.

The final ford across the river was deeper than the others. We realized it was imperative to keep our clothes dry to stay warm. I had only met Nancy a few times before, but without hesitation we undressed from the waist down at the near side of the river. Holding our clothes and boots above our heads in one hand, we grasped each other’s hands for balance as we crossed. I looked over at her and said, with a twinkle in my eye, “Nancy, welcome to the family.”

We laughed until our sides hurt. It was a good relief from the tension. My humor masked how bad I felt for her and how scared I was for all of us. Peggy’s love of adventure had turned our innocent outing into a life-threatening situation. The worst thing, beyond our physical danger, was that we were going to miss meeting Nelson Mandela.

It was dark when we reached our original campsite. We had been hiking for almost ten hours and had eaten only a few raisins, two power bars between the six of us, and a few tiny apples. Our water was almost out. Richard shared his water bottle around so he could fill it from the river. At that moment his leg went into spasm. His body was severely lacking in electrolytes anyway from the Gleevec, and the lack of food and water exacerbated the cramp in his leg and a swiftly oncoming headache. We were now entering a stage of crisis.

I had one packet of Emergen-C in my first-aid kit. I tore it open, poured it into his canteen, and gave him two Aleves from my bottle of pills. Luckily, it worked. We made our way down over rocks to our former campsite.

The temperature dropped like a stone to forty degrees. We huddled together in our shorts and light hiking shirts to warm ourselves. I fumbled around in my backpack and found an extra long-sleeved shirt and hat for myself and a spare hat, shirt, and socks that I passed around to the others.

Paul stirred the fire to see if there were leftover embers from our campsite that morning. Luckily there were. He and my brother collected enough wood to last for the night and revived the fire. We had nothing to do but lie down in the sand and wait for our rescue.

There was no moon, nor was there any habitation or electricity for fifty or more miles in any direction. The stars were as bright as I imagined them to be at the time of cavemen. We were surviving much like prehistoric humanoids depicted in the petroglyphs, cold, hungry, and empty of anything but each other’s company. The fire was a godsend. It warmed our heads as we lay near it. Laughter covered the undercurrent of worry and fear. Here we were in one of the most remote places on earth, huddled together in survival mode, all on Nancy’s first family trip. Peggy was clearly relieved that we weren’t expressing our anger at her. We were furious and disappointed, but this was not the time to verbalize our feelings.

I wondered aloud, “Where is Ian? Has he run into a leopard? Has he found the truck?” There was nothing to do but wait and stare at the magnificent stars. I thought about the tawny eagle and realized it probably had been a sign. Next time I would stand up to my sister.

An hour or so later we heard footsteps. Peggy jumped up and yelled. It was Ian. He had not found help, but he was back safely. He pulled a space blanket out of his daypack. It was just big enough to share with Peggy. They lay on the other side of the fire while the other four of us spooned each other for warmth. Any time one of us needed to turn over, the rest of us rolled with them like hot dogs on a grill. This produced loud giggles from Nancy and me, but we seemed to be the only ones who didn’t sleep. Despite our being in the middle between Richard and Paul, we were too cold to doze and had to get up every hour to warm ourselves by the fire.

The good thing about having no food or shelter is that, if you survive to the morning, all you have to do is get up and start moving. That is what we did. As we had not been rescued, we all filled our water bottles from the river and started walking up the road that the Land Cruiser would come down, knowing we would intersect it at some point. The plane that was supposed to pick us up yesterday would soon be looking for us again.

Richard kept saying, “I just wish we had a mirror.” The words had played in my head since yesterday. We must have something, I thought to myself. I had already looked in my first-aid kit for a mirror. I had also checked everyone’s clothes for something shiny. No luck again. Ian walked in front of me with his backpack on.

We heard the plane in the distance, along the river, starting its search. Peggy and Nancy tore off their white shirts and waved them together in the air. The plane circled twice but didn’t see us. We were beginning to despair. I kept thinking we have to have something that will work as a mirror. My eyes fell on the netted side pocket of Ian’s backpack, and suddenly it clicked.

“Ian’s got the space blanket!” I shouted. “That’s our mirror.”

Ian dropped his pack like a hot potato. I pulled the space blanket out and Peggy and Nancy spread it with Paul and me. A three-by-five-foot shiny reflection gleamed at the plane on its third (and probably last) time around. This time it dipped its wings and headed straight back to the airstrip. Nancy and I burst into tears. The others hooted with glee.

I was wiping tears from my eyes when I heard Peggy and Richard say, “Eileen, you are our hero.” They would tell the story many times to the rest of my family. I felt seen. And I’m glad we all lived to tell the tale.

Two months later, Paul and I returned to South Africa to take our sons on safari. It was our last window of opportunity before they both got too involved in their work to travel. They had never been to Africa, and we wanted to introduce them to one of the great leaders of the world. Peggy made up for our mishaps in Namibia and kindly arranged for the four of us to have a private meeting with Nelson Mandela.

You know you are in the presence of a strong man when he sits with his back to the door. Nelson Mandela was seated in a wing chair facing away from us when we were ushered into his office in Johannesburg. We took turns shaking his hand and he invited us to sit down around him.

Peggy had told us to call him Madiba, a respectful greeting referring to the name of his clan and its nineteenth-century Thembu chief.

After we were seated, his assistant, Vimla Naidoo, asked if we would like something to eat or drink. A table at the side of the room had a spread of soft drinks, cookies, and sandwiches. We were too excited to eat but, to be polite, we all asked for water.

Madiba jested. “I will have Cuban rum, Vimla.” To which Vimla responded, “Sorry, Tata, but we are all out.” The tone of her voice told me she had heard this joke before. Right away I felt at ease.

I began the conversation by thanking him for seeing us and reminded him that my sister Peggy had arranged this meeting. He had just turned ninety. I did not expect him to remember how my family of four came to be with him now, but the mention of Peggy brought a smile to his remarkably wrinkle-free face.

“I am very fond of your sister and of your father,” he said. “How is your father?” I told him he was very well. My dad is three years older than Nelson Mandela, but he considers Mandela one of his heroes. I told him this.

“Yaas. Yaas,” he said thoughtfully, nodding his head in the affirmative. His voice was soft but gravelly. “And he is one of mine.”

We had come prepared with questions. I went first. “Madiba, what is one thing you have learned in your life that you would like to share with our sons?”

He thought a minute. “It is never only one person who makes change and it is important to remember that. It is always a collective effort with one person being put at the head of the pack. One person is necessarily more visible but there are many others who are of equal importance and influence to the cause.”

I knew he was thinking of his role in South Africa. I thought back to my days with the CASEL leadership team. He was right. Many people gave him all the credit for ending apartheid. But he knew differently. This was not false modesty. He really meant what he said. Then he moved on to his other favorite subject, education.

“With education no one will starve.” He looked deeply at both Adam and Danny, as if taking them in for the first time.

I thought of one of the quotes I had underlined in his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, which I was holding for him to inscribe before we left.

Children wander about the streets of the townships because they have no schools to go to, or no money to enable them to go to school, or no parents at home to see that they go to school, because both parents (if there be two) have to work to keep the family alive. This leads to a breakdown in moral standards, to an alarming rise in illegitimacy and to growing violence which erupts, not only politically, but everywhere.

He could have been talking about our country. I felt sad to realize that the situation is very much the same in the United States today.

Madiba turned to Danny and continued. “When I was a child I was a good stick fighter. It was the tradition of my Khosa tribe to stick fight. The left hand was used for defense and the right for attack. I have scars.” He pulled up his loose sleeve to show him. “I am proud of these scars because they remind me of my roots. But I think that stick fighting should be eliminated because it is violent.”

Danny challenged Nelson Mandela as only a twenty-year-old can do. “But if stick fighting is an intrinsic part of your clan’s culture, wouldn’t its elimination be erasing part of your cultural heritage?”

Madiba’s eyes twinkled. He liked the challenge of youth. “Yaas. Yaas. That is gooood for you to think about these things. I would eliminate stick fighting but I would keep the dances. I like my traditional dances. I always join in when I go back home. I would like for my people and other cultures to keep such traditions.”

There was a pause. I thought of my favorite quote from his book:

No one is born hating another because of the colour of his skin, or his background, or his religion. People must learn to hate, and if they can learn to hate, they can be taught to love, for love comes more naturally to the human heart than its opposite.

I felt a lump in my throat. How could this man, who had suffered so many indignities, still call for the human heart to open to love? It is one thing to write about it. It is quite another to live from a place of love, even in the face of bigotry and hate.

It was Paul’s turn to ask him a question. “What advice would you give our sons?”

Mandela summed it up in one word. “Travel.” He turned and looked at Adam, perhaps seeing something beneath his skin. “Have you ever been to Georgia, Russia?” Adam blushed and said, “No? But we housed an international student from Georgia a few years ago.” Madiba continued, “Yaas. Yaas. There are some interesting things going on over there. It is important to travel. It gives you perspective.”

Madiba had already opened our eyes. He was right about traveling. I was glad Paul and I had made the effort to bring our boys to South Africa, for it is easy to remain isolated in the United States. We have to see other cultures with our own eyes to gain perspective. I had told the boys before we met Madiba that in 1985, the year Adam was born, talks for reconciliation against apartheid were beginning. In 1988, when Danny was born, the US Congress passed its sanctions bill and other countries began to impose sanctions against South African apartheid. In 1990, the year their paternal grandmother died, Madiba became president of the African National Congress. At the time, this made little impression. They would look differently now at these events in history.

I remembered back to how shaken my parents were after first visiting South Africa together in 1960. I was eight years old and they were gone for six weeks. Every day I followed their itinerary on a map with a red pencil. My mother hated being gone so long and she came home distraught over seeing horrific conditions of racism and brutality toward black South Africans. It changed how she viewed black people and she despaired that there would be a bloodbath before things got better. In 1994, two years before she died, she got to see Nelson Mandela become president of South Africa. It was a great day in our house and a huge step forward in the world. Her stories influenced my sister Peggy’s decision to devote her life to eradicating racism and poverty.

Our meeting with Mandela had originally been scheduled to last for fifteen minutes. It was now approaching an hour. Vimla gave me the nod and I asked Madiba if he would be willing to inscribe my copy of his book. Vimla wrote down the correct spelling of my name and Madiba inscribed it with the following words: TO EILEEN. BEST WISHES. MANDELA. He had already given my family and me the best wish we could have imagined.

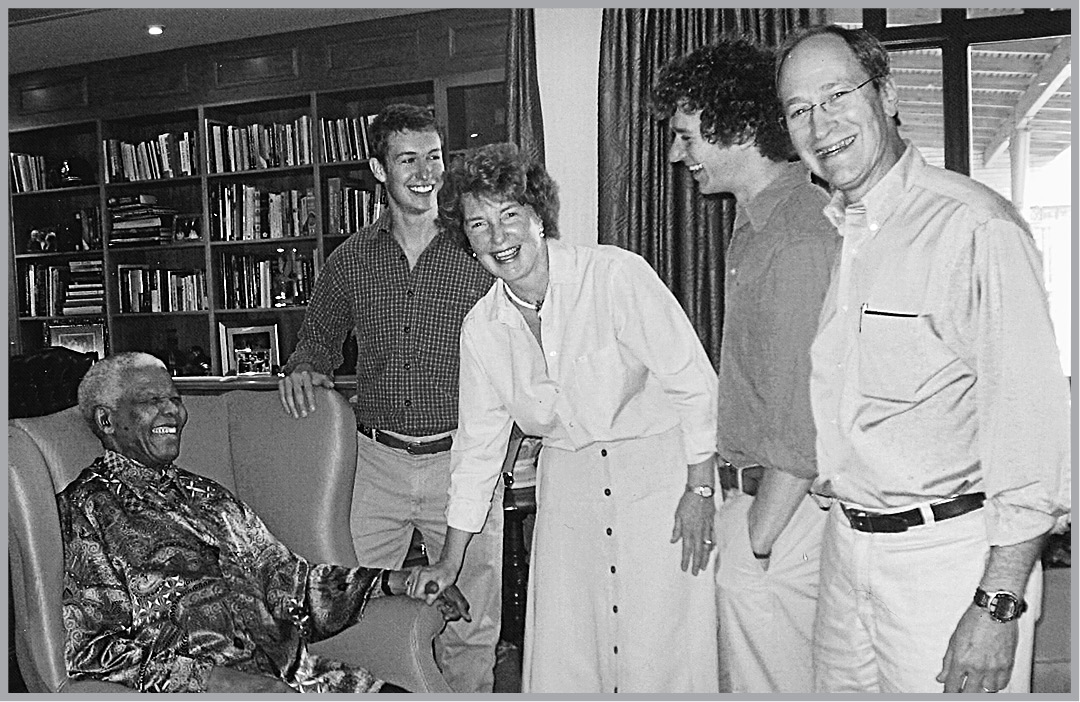

Vimla took a photograph with my camera, which I now have framed in my office. The four of us are standing around him as he remains seated in his wing chair. Paul, Adam, and Danny are on either side of him. I am leaning over, holding his hand. He is looking directly at me and we are laughing. Despite all the troubles in the world, we are connected for a moment by something resembling love.

Growald family with Nelson Mandela, 2008