1.

THE STORY I DIDN’T WANT TO TELL

John D. Rockefeller was my great-grandfather. For years, my siblings and I tried to keep this a secret because his name created such a buzz. Adulation, judgment, envy, and endless curiosity flew around us like a swarm of bees. I was afraid of the sting. People saw us as different, and that set us apart. Their preconception of my family as akin to royalty contributed to my sense of isolation and loneliness.

I live with anxiety and gratitude, just like the generations of Rockefellers before me. Without anxiety and the desire to heal it, I would not be writing this story.

The physical comforts and circumstances of my life were undeniably different from most people’s. I grew up in big houses with lots of servants. I was given an allowance that could probably be considered large, and I went to school in a chauffeur-driven limousine. We called it the “hearse” or “curse” because, before the oldest ones left for boarding school, we needed a car large enough to carry all six of us. It had two jump seats in back. My siblings and I (and, it turns out, my cousins, too) jumped out a block or two before we arrived at school so we could walk up to the door just like everyone else. We tried to hide who we were because we wanted to fit in, and also because my mother trained us not to stand out.

As an heir to the Rockefeller legacy I have found that real richness and power comes not from the amount of money but from our connection to ourselves and one another. I am just as much “Eileen” as I am “Rockefeller.” I struggle with my weight. I am getting more lines in my face every year. I have fights with my husband, I get really impatient when I have to wait for a long time in the grocery or gas line, and I hate going through airport security. Sound familiar? And just like you, I am also unique.

I am part of a long line of venture capitalists and philanthropists. It’s hard to talk about my grandfathers without them taking over. Their accomplishments overwhelm me. I feel small and insignificant in comparison.

I come from a family of ledger keepers. We have been practicing for over 150 years. It started in 1855, during the Great Awakening of our nation, a strong religious revival movement among Protestant denominations. A fifteen-year-old boy felt compelled to drop out of Cleveland Central High School. He would have had to have studied Greek and Latin to qualify for college. That wasn’t his plan. He needed a steady income to support his mother and siblings. His father, William, was a charismatic land speculator, referred to as “Big Bill.” He occasionally sold stolen horses and left home for extended periods of time, selling snake oil remedies, which he promoted as medicinal cures. William was rumored to appear in marketplaces acting as a mute. He held a sign that read: “Dr. William A. Rockefeller, the celebrated cancer specialist, here for one day only. All cases of cancer cured, unless too far gone, and then can be greatly benefitted.” He also cultivated a second, simultaneous family. His philandering lifestyle, compounded by absence and scant amounts of money, left John D. Rockefeller, the boy, extremely anxious. He kept track of every penny, but it often wasn’t enough to pay the bills; he vowed to be more reliable than his father. The family’s well-being depended on it. He wrote down his minister’s advice in his little book: “Get money, get it honestly, and then give it wisely.”

Just weeks prior to graduation he left high school, bypassed college, and enrolled in a nearby business school, pushing himself to finish the six-month program in half the time. Careful bookkeeping was key. His first job at the age of sixteen was as an assistant bookkeeper for Hewlett and Tuttle, a firm selling products on commission, in Cleveland. They paid him nothing for the first three months, waiting to see how he would do. He was so relieved at the opportunity to support his family that he celebrated his first day of salaried work, September 26, 1855, for the rest of his ninety-seven years.

The daily practice of noting the inflow and outflow of money had begun. He applied the discipline to himself as well, creating a set of books in which he tracked his personal finances. They have been carefully preserved in the family archive. In reading them, I imagine him walking to his desk in a sparsely furnished room. Each night he strikes a match to the whale-oil lamp and turns up the wick. The shadow cast by its light elongates his tall, slender frame and straight-angled nose across the wooden floor. He lifts his tailcoat neatly over the back of the chair and, with his head bent, he dips his quill into the inkwell and notes the day’s expenditures:

|

January 2 |

1 week’s Board |

3.00 |

|

January 2 |

2½ yards cloth for pants |

3.13 |

|

January 5 |

Making of same |

2.25 |

|

January 5 |

1 Pare [sic] of rubbers |

1.25 |

|

January 6 |

Donation to Missionary Cause |

.06 |

|

January 6 |

Donation to the poor in the church |

.10 |

The pants were well earned, he reassures himself, even if they did cost more than a week’s salary. He can afford them now. Just before Christmas, the firm paid him fifty dollars for his first three months of work and set his salary at twenty-five dollars a month. He is on his way. His mother’s fears will be eased, but he needs to remain diligent and to present himself well as the honest and hardworking man he has become.

His thoughts drift to Laura. He heard that she had been the valedictorian of their class. What had she thought about his dropping out? Or had she even noticed? “I Can Paddle My Own Canoe” was the title of her address to the class. What did a woman like her value in a man? A respectable pair of pants wouldn’t hurt, but she would be looking for something more. She was a churchgoer, a Congregationalist, and had progressive principles; that was clear. Hopefully, she had come to appreciate that he did, too, and did not mind his Baptist roots. Maybe he would speak with her after church sometime soon. But no more daydreaming; there was work to be done.

Great-Grandfather not only spoke with Laura. He also began courting her, sometimes with his ledger books in hand. I envision them sitting together on a bench in the garden of her parents’ home on a Sunday after church, turning the pages and talking quietly. It’s not my idea of a romantic courtship, but it had to start somewhere.

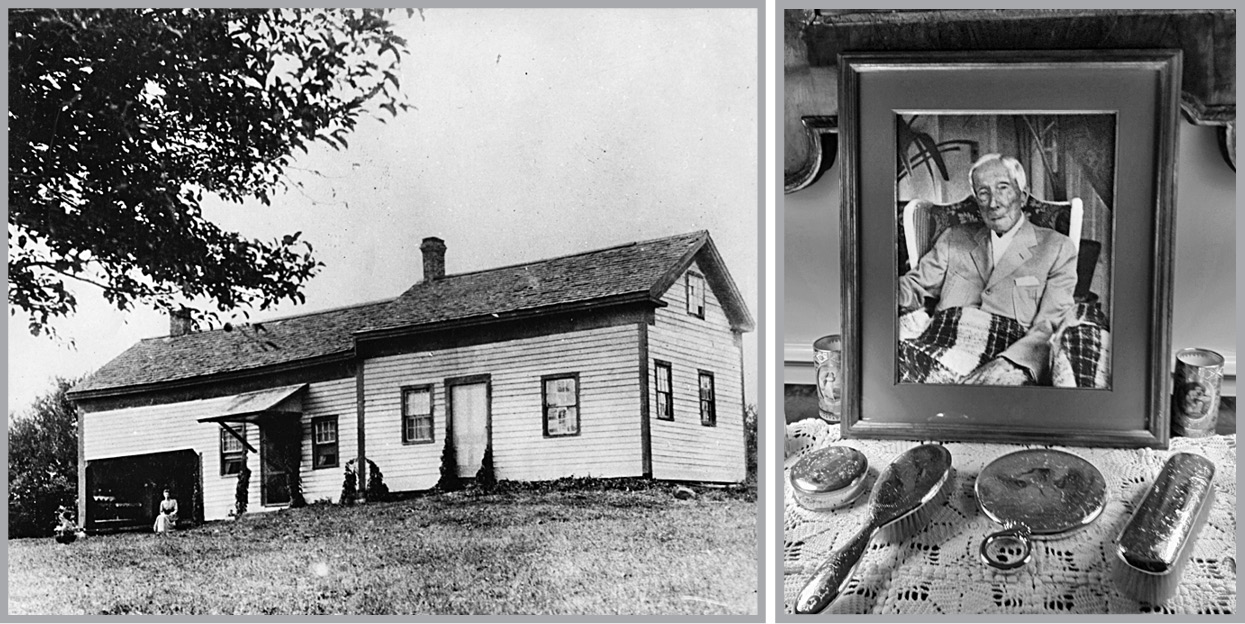

I wonder what the ledgers revealed to her? What evidence of character, worthiness, or desirability did he hope they would convey? Of which entries was he most proud? Was it his first paycheck? Was it giving money to a black man in Cincinnati so he could buy his wife out of slavery? I wonder what he read to Laura that pulled her heartstrings? I never knew him, but my father did. He keeps a picture by his bedside that he took in Ormond Beach, Florida. John D. Rockefeller’s slender frame is seated in a wooden wheelchair with a plaid blanket on his lap and boney fingers clasped on top. His eyes look lovingly, though somewhat vacantly, toward my father. He died just weeks after the picture was taken. I can see his whole life scanning before him, from his courtship to his favorite grandson.

In 1864, my great-grandparents, John Davison Rockefeller Sr. and Laura Celestia Spelman, married. America was at war with itself over issues of division, enslavement, and morality. John D. would deal with some of these same issues internally. The laws of family and tithing, learned at the knee of his Northern Baptist mother, Eliza, called for daily Bible readings and persistent self-examination. He believed his work was a calling from God. His wife is best known for her and John’s major contribution in 1881, to Spelman College, in Atlanta, Georgia, to educate black women.

Young men, like his brother, Frank, were walking down country roads with heavy guns slung across their shoulders when Great-Grandfather’s Cleveland company started extracting oil for kerosene that would light the soldiers’ encampments at night. It was the start of a new era. John D. borrowed from his father’s entrepreneurial spirit and predilection for cure-alls in developing the greatest snake oil of the modern world. He consolidated oil production and distribution on a scale that would spawn both cures and cancers, lighting the way to modern transportation, road networks, and industry. He could not have known then that one hundred and some years later, burning oil would contribute to the warming of Earth’s atmosphere.

Senior apparently wanted his children to learn temperance from ledger keeping. They earned allowances and noted inflow and outflow line by line in their own ledgers. Luxuries were not in evidence. John D. Jr., the youngest of five and the only son, wore his sisters’ remade hand-me-downs until he was eight. When he became a father, he taught the third generation to be ledger keepers as well. My own father’s ledger shows him earning two cents apiece for swatting flies, being docked five cents for lying, and spending his first dollars at age eleven on a little pot made by a Pueblo Indian woman.

My great-grandfather’s success in the oil business made him the world’s first billionaire. The abundance of money more than compensated for his early fears of scarcity. Yet, throughout his life he kept scrupulous ledgers, balancing everything he earned, spent, or gave away to the point of obsession. As a devout Baptist, he practiced tithing—giving away 10 percent of his income. He passed this tradition down to his son, and together they taught the next generation a philosophy of philanthropy that continues to this day: save one third, spend one third, and give away one third.

My great-grandfather called upon the assistance of his son and advisers in giving away the equivalent of tens of billions in today’s dollars. Grandfather, John D. Jr., graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Brown University in 1897, and after working for thirteen years at the Standard Oil Company, spent every day of the rest of his life helping to give away his father’s money. His fervent sense of loyalty and duty would help shape his father’s and his image while doing good throughout America and the world. He lived in a time of expansionism, when the very word America represented a land of opportunity and hope. His work was not without its consequences, however. Despite father and son’s unprecedented success, they were periodically subject to public excoriation over the practices of some of their businesses. They contracted what might have been stress-induced illnesses.

In his early fifties, Senior suffered permanent hair loss from a viral disease called alopecia, sometimes associated with stress. Junior had his first nervous collapse at the age of thirteen. I suspect it stemmed from the expectations and implications of being his father’s only son. He was given a year of hard physical labor to regain his emotional strength. This would be the first of periodic collapses throughout his life, along with crippling headaches. Nature became his therapy and he passed along its value to subsequent generations.

I like to think he found some relief in the time he spent with his grandchildren. My only memory is of visiting him at his house in Maine when I was six or seven years old. He came to the door to greet me. I remember his wire-rimmed glasses, and he smelled faintly of cedar. He sat down on a chair next to me and taught me how to play Chinese checkers. I was allowed to choose the yellow marbles, yellow being my favorite color.

The list of his accomplishments for the benefit of the common good is a book in itself, and many have been written. Though most of us in my extended family no longer keep ledgers, we still practice philanthropy and service, balancing questions of worth and relationship with opportunities and responsibilities. We are free to spend our money as we wish, but we have inherited the values passed down from my great-grandfather, to give no less than a third of our income away annually, and to give our time to causes such as social justice, the arts, and land conservation. We have promoted innovations in medicine, education, and science. Philanthropy is the glue that has bound us through seven generations.

My great-grandfather and the two generations that followed him set the bar high for my cousins and our offspring. “It is easy to give money away,” my grandfather and father used to say, “but it is not easy to give it well.” The truth of this statement follows my family around like a bee that won’t quit buzzing. We have been given enormous opportunities, but they come with an equal measure of expectation. It takes a family as large as mine to balance the ledger of my grandfathers’ legacy. Personal stories help me to see us not as icons but as ordinary human beings.

My great grandfather, John D. Rockefeller’s childhood home in Moravia, NY