CHAPTER FIVE

The March to the Summit

IN 1746, Gaspard Monge was born in the French town of Beaune, which is located near Dijon in the heart of Burgundy wine country. The son of a peddler, Monge showed a knack in his youth for architectural drawings. While still a teenager, he drew a large-scale, incredibly detailed plan of his hometown, which caught the attention of a military officer who helped Monge gain entrance to a military school in northern France. Owing to his common origins, Monge was not admitted to the school proper, which was reserved solely for aristocrats, but he was allowed to study drafting and surveying in a separate part of the facility. This arrangement was not entirely satisfactory to him, as he longed for a position that would enable him to utilize his talents more fully.

Monge got his chance a year or so later: He was asked to determine the best place to position guns at a proposed fortress so its occupants would be well protected from enemy fire. He used geometric techniques, which he developed on his own, to solve the problem, completing the task so quickly as to arouse suspicions in some quarters. Nevertheless, his mathematical skills could not be denied, and Monge was finally given the opportunity to cultivate them.

He started teaching physics and mathematics in 1768, conducting research on partial differential equations as well as applications of calculus to geometry. In the 1780s, after assuming a mathematics post in Paris, Monge began studying nonlinear partial differential equations of a special kind, which were eventually called Monge-Ampère equations—a designation that presumably reflects some modifications made several decades later by the French scientist André-Marie Ampère, who was best known for his contributions to the theory of electromagnetism and after whom the unit of electric current, the ampere, was named. (I say “presumably” because I’m not aware of any actual contributions that Ampère made to this subject, though he may have done so. On the other hand, sometimes a name is stuck on an equation for no apparent reason.)

Monge’s story shows, first of all, that a career in mathematics can be launched in indirect and unexpected ways, although some underlying aptitude for the discipline is always helpful. But my principal motivation for bringing up this anecdote stems from the fact that the Calabi conjecture can be expressed in terms of a Monge-Ampère equation. This kind of equation is nonlinear, as mentioned before; has at least two independent variables; and is also “complex,” meaning that it involves complex numbers. The challenge, from my end, was that no one had ever solved a complex Monge-Ampère equation before, except in the simplest, one-dimensional case. But in tackling the Calabi conjecture, the higher-dimensional form of these equations, which had so far defied resolution, would have to be solved too. This was the big stumbling block and the reason why little progress had been made on this problem twenty years after Calabi first raised it.

I started working on Monge-Ampère equations at Stanford during the 1973–1974 school year, about two centuries after Monge began formulating his ideas on the subject, although I was lucky to have some mathematical tools at my disposal—including a few I devised myself—that he probably could not have imagined. I first looked at Monge-Ampère equations defined over real numbers, which relate to the curvature of a surface. The real equations are easier to manage than the complex variety, and I enlisted the help of my friend S. Y. Cheng, who often came down from Berkeley to visit. Our plan was to build up some mastery over the real equations before taking on the more demanding complex ones.

Fortunately, Cheng and I had some success. We solved a Monge-Ampère–type equation that appeared in the famous Minkowski problem. That problem, in very simplified terms, relates to showing whether an object with a distinct kind of curvature could exist. You can probably see why this problem appealed to me, as I had been intrigued by the connection between geometry and partial differential equations ever since taking my first course with Morrey four years earlier. This was, indeed, the principal thrust of the emerging field of geometric analysis, whose development I was doing my best to foster, while encouraging colleagues like Cheng, Schoen, and Simon to join me in this effort.

The general strategy for solving equations of this sort, as discussed in the previous chapter, involves coming up with a series of approximate solutions and narrowing down the range until it can be shown that this process will eventually converge on an actual solution. My hope was that I could eventually do the same with the complex Monge-Ampère equation that encapsulated the Calabi conjecture. Proving that a solution to this equation existed would be equivalent to proving the existence of the extraordinary geometric spaces postulated by Calabi—spaces endowed with a special symmetry and distinct curvature that also satisfy the Einstein equations.

In the spring of 1974, Chern invited me to Berkeley to give a talk. The Russian-born mathematician Mikhail Gromov was then visiting Berkeley for the first time, where he was treated like royalty owing to his reputation as one of the world’s great geometers. I’d had a not-so-wonderful encounter with Gromov about six months earlier. At that time, I had used geometric analysis to prove that a certain space had an infinite volume. Gromov claimed that my proof must be wrong although I’m not sure he really understood the approach I had taken. In the end, this result has held up quite well.

I was discussing a different subject at Berkeley, which had to do with the “spectrum” of a geometric space—the resonant, vibrational frequencies produced by deforming a space, which are similar, in principle, to the characteristic frequencies produced when a drumhead is struck and its surface thereby deformed. Gromov took issue with me once again, announcing in the middle of the talk that he considered my line of attack to be fundamentally unsound. The proof I was then discussing, as with the previous proof we had debated about, relied heavily on nonlinear partial differential equations—an area that Gromov did not specialize in. It’s possible that he just did not understand my proof. But rather than asking me to explain the argument, he instead contended that I didn’t know what I was talking about.

That appeared to be his modus operandi, acting as if I were a lowly student who hadn’t done his homework properly. He took up much of the time allotted to me in the seminar to voice his skepticism about my work. What it came down to, as best I could figure, was that he did not regard geometric analysis as a worthy pursuit. Any theorem in geometry, he insisted, must be proved by geometric means. I, of course, had a different opinion, and the whole premise of geometric analysis depended on the strength and validity of that conviction.

The seminar was not a great success and hardly could have been, owing to Gromov’s loud and frequent interruptions. But afterwards I spent hours explaining to him my new result and my earlier proof on infinite volume, answering one doubting question after another. I finally showed him how to translate my analytic method into strictly geometric terms, at which point he relented, giving tacit approval to my results.

I later had similar though much more cordial interactions with Bill Thurston, a fellow graduate student of mine at Berkeley who had since made a name for himself in geometry and topology. Thurston’s approach to geometry was somewhat akin to building geometric spaces, or manifolds, out of small pieces like Lego blocks and in that way delineating their inner constitution. I took almost the opposite strategy, using differential equations to get a handle on both the underlying structure of objects and their overall topology. The two philosophies were quite different, although both have ultimately proved successful. I should stress that Thurston was a really deep thinker and a true original. While he did not always go into great detail in some of his arguments, the ideas he formulated have had a profound and lasting influence on the field.

I learned a valuable lesson from my exchanges with Gromov and Thurston and other conversations of a similar nature: I would have to overcome a lot of resistance among some mainstream geometers and topologists before the tools of geometric analysis were widely embraced. But I suppose that is the way when all new techniques, especially dramatically different ones, are brought to the fore. Such a guarded response can serve as a helpful precaution, but it can also hold back progress in a field.

I didn’t let any of the skepticism dampen my enthusiasm for this line of work, which seemed to be progressing well enough. Nevertheless, I suffered a personal setback in June 1974. Yu-Yun, who’d been a postdoc at Stanford, got another postdoctoral position at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory—a U.S. Department of Energy lab located on the Princeton University campus. This was an excellent appointment for her, and ordinarily I would have been thrilled. But it meant that we would soon be on opposite ends of the country again. She left shortly thereafter, driving to Princeton with her mother.

A surprise visit by Tat Chui, my old pal from Hong Kong, and his girlfriend served as a welcome distraction. It turns out that his girlfriend, who was soon heading back to Hong Kong, was on the verge of breaking up with him. We decided on the spur of the moment to go to Yosemite National Park, heading out that evening in my car and arriving in the mountains late at night. This brief outing turned out to be just the thing for all of us. Breathtaking views from lofty peaks have a way of magically taking you outside of your own head, offering a new and broader perspective on the world. We had such a good time during this trip that Tat and his girlfriend decided to get married.

Although I was happy for them, I was on my own—at least for the time being. And I did what I always did in such situations: I threw myself into my work. I was used to working extremely long hours—often going late into the night and occasionally falling asleep at my desk—a lifestyle that was, admittedly, not ideal for nurturing a relationship. But now that I was alone, I had no shortage of mathematical projects with which to fill my time and thoughts, especially the Calabi conjecture, in which I was deeply and irretrievably immersed.

Before taking on the complex Monge-Ampère equation that lies at the heart of that conjecture, Cheng and I felt that some additional preliminary work was still needed. In 1974, we started to work on the so-called Dirichlet problem, named after the German mathematician Peter Gustave Lejeune Dirichlet, without realizing that Eugenio Calabi and Louis Nirenberg were working on it at the same time. Classified as a “boundary value” problem, the basic idea can be summed up as follows: Just as solutions to simple equations might consist of a set of points that define, for example, a circle or parabola, the solution to more complicated differential equations could define an entire surface. If all you know is the boundary of that surface, the Dirichlet problem asks, can you use that knowledge to find all the interior points that make up the surface and at the same time satisfy the equation at hand? The standard procedure, as with the previous exercises, involves making a series of estimates, or approximations, that collectively allow you to home in on a function that solves the specified partial differential equation.

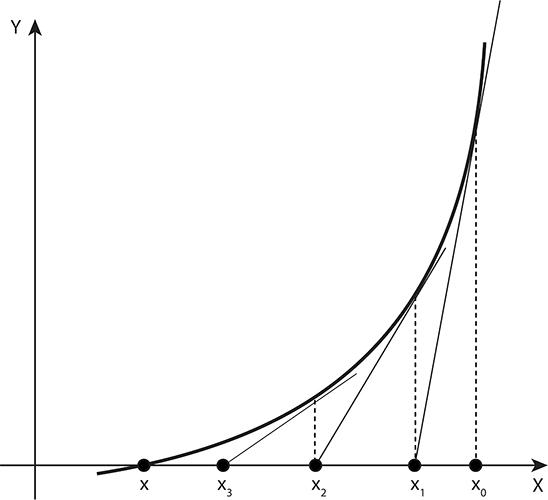

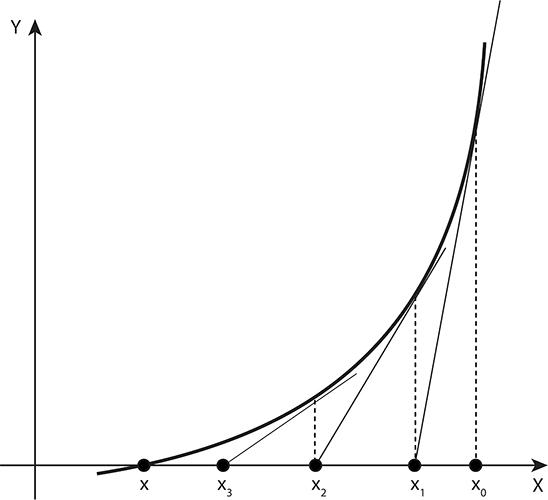

While the estimation methods used to solve the Dirichlet problem and Calabi conjecture are too complicated to present here, we can instead provide an example of a very simple approximation technique called “Newton’s method.” To find the roots or zeroes of a function whose output is real numbers, places where a particular curve crosses the X axis, we start off with our best guess—a point we’ll call X0. We then take the tangent of the curve at X0 and see where the tangent line crosses the X axis (at a point we’ll call X1). As we continue this process, assuming our initial guess is not too far off, we’ll come closer and closer to the true answer, point X. (Based on original drawing by Xianfeng [David] Gu and Xiaotian [Tim] Yin.)

Nirenberg was scheduled to give a plenary talk at the International Congress of Mathematicians, which would convene in Vancouver in August 1974. In this talk, he intended to present the solution to the Dirichlet problem based on the work he and Calabi had done. Chern, however, told us that Calabi and Nirenberg had subsequently found a mistake in the preprint they had circulated on the subject that invalidated their solution and left the problem up for grabs.

I told Chern of my confidence that Cheng and I could solve this problem. Since Nirenberg was coming to Berkeley sometime in the spring of 1974, Chern arranged for the four of us to meet for lunch at Louis’ Restaurant in San Francisco, located on the beach not far from the Golden Gate Bridge. Cheng and I went through our proof carefully the night before to make sure there was no problem, as Nirenberg was a leading authority on partial differential equations and we didn’t want to embarrass ourselves. We uncovered a mistake in our argument, but after further work, we felt that we had fixed it by 2 a.m. Before lunch, we described our solution to Nirenberg, who thought it sounded reasonable. Cheng and I were pleased but later uncovered more mistakes when we went through the proof again that night. The errors were frustrating, but they helped us learn how to deal with this kind of equation. Six months later, we figured out how to fix them and ultimately solve a weaker version of the Dirichlet problem. Nirenberg and others solved a stronger version of the problem about ten years later.

But the San Francisco meeting with Nirenberg proved helpful to me in another way. Earlier in the year, Robert Osserman had nominated me to become a Sloan Fellow—an honor for a young assistant professor—which would allow me to spend a year wherever I wanted, with my salary paid in full by the Sloan Foundation. I initially thought I’d use the fellowship to go to Princeton, where I’d have the chance to see Yu-Yun, with the hope that she and I could renew our relationship—and maybe more.

I wrote to Wu-Chung Hsiang, who had moved to Princeton from Yale, to see whether I could spend at least half of my fellowship year in Princeton. A few days later he told me the math department had no office space available. Now that I have some familiarity with these things, I suspect that space for me at Princeton could have been found if Hsiang and others in the department wanted me there. I realized, belatedly, that I might have had better luck by writing to the department chair. Instead, I went through an acquaintance—a possible mistake given that the person I knew may not have been all that fond of me. (The situation was reversed a couple of years later, ironically, when the Princeton math chair asked Hsiang to call me to offer a professorship. On that occasion, I turned him down, though I was not at all acting in spite; I just wasn’t ready to move to Princeton then.)

Fortunately, Nirenberg said without hesitation that I should spend the fall of 1975 at New York University’s Courant Institute, which was not too far from Princeton. Nirenberg was enthusiastic about my coming to Manhattan, and by the end of lunch it was essentially a done deal.

Once the Dirichlet problem (in its weaker form) was behind me, I turned my attention toward the Calabi conjecture. My strategy was pretty straightforward: I planned to take everything I had learned from the work on real Monge-Ampère equations and transfer that, to the extent possible, to the complex case. Cheng, who had little expertise in complex geometry, bowed out at this stage to undertake projects closer to his interests and expertise. Coincidentally, he was going to be at Courant too, which would enable us to spend time together socially, as well as continue our joint efforts to build the foundations of geometric analysis.

Going to New York, which I did in August 1975, was beneficial to me for another reason. Thanks to my Sloan Fellowship, I had no teaching responsibilities and was free to work on the Calabi conjecture, or any other mathematical problem, as much as my time and energy would allow.

I intended to take full advantage of that opportunity, though my first order of business was finding a place to live in Manhattan, where accommodations were very expensive. Studio apartments were going for $200 per month and up, which was more than I wanted to spend. Fortunately, I caught a break from Jürgen Moser—a former Courant director and friend of Chern’s—who had access to a friend’s rent-controlled apartment on Spring Street, near New York University. The rent was just $50 a month, a fabulous deal. Moser was not supposed to rent out the apartment because it was not leased in his name, so I was told to avoid conversations with the owner who, coincidentally, was Chinese. He didn’t speak English, though he spoke Cantonese, which I knew very well, but I had to pretend I didn’t understand a word he said. And if anything went wrong with the apartment, I had to tell Moser, who would take care of the problem himself. Given all that, it was rather amazing, and incredibly generous, for Moser to have done this for me, a virtual stranger.

While Courant provided a wonderful place for me to work, my main purpose in going there, as opposed to any other destination I might have chosen for the fellowship, was to be close to Yu-Yun. We had had little contact since she had left Stanford almost fifteen months earlier. But if I were going to date her, and take her places outside of the campus, I would need a car. Unfortunately, I didn’t have a credit card then and was unable to rent a car in New York City without one. I got Stanford to write a letter on my behalf explaining I was on the faculty there and temporarily at Courant, but that held no sway over the car rental agencies.

I started to panic because, without a car, my whole plan of spending time with Yu-Yun, which had taken me to the East Coast in the first place, would be seriously jeopardized. Luckily, I came across a high school friend who was in New York working as a travel agent. He told me about a low-end, “rent-a-wreck” kind of establishment that would loan me a vehicle after I put down a hefty cash deposit. The car I got was in barely drivable condition and nothing great to look at, but it would have to do, given the limited options available to me.

Despite its shabby appearance, the car was good enough to get me to Princeton, and I visited Yu-Yun there when I could. She was tied up with her research, just as I was preoccupied with my work on the Calabi conjecture, but it felt like I was making steady progress on the latter. Although I wasn’t ready to attack the summit quite yet, a viable route to the top seemed to be emerging.

The proof, as I structured it, rested on four separate estimates to the critical complex Monge-Ampère equation: the so-called zeroth-order, first-order, second-order, and third-order estimates. The solution to a Monge-Ampère equation, as I’ve said, is a function, and the whole point of this exercise is to establish some bounds on the function that show it cannot get too big (in the positive direction) or too small (in the negative direction)—to show, in other words, that the function cannot go to infinity. The zeroth-order estimate tells you the maximum value the function can attain. The first-order estimate tells you the maximum value of the function’s first derivative. One needs to demonstrate, more specifically, that the first derivative cannot get too big, which is equivalent to showing that the function cannot fluctuate too rapidly. The second-order estimate, similarly, tells you the maximum value of the function’s second derivative. One must show, again, that this estimate is bounded, meaning that the first-order derivative does not fluctuate too wildly. The same idea holds for the third-order estimate and up. These higher order estimates provide information on how the function changes—how big those changes are and how rapidly they occur.

In the summer of 1975, just before going to New York, I had succeeded in pinning down the second-order estimate. During the few months I spent at Courant, I made something of a conceptual breakthrough. I realized that, at this point, all I needed to get was the zeroth-order estimate because with the zeroth and second in hand, I could also derive the first-order and third-order estimates. In other words, the entire proof now rested on determining a single estimate, the zeroth order. And that estimate depended on my showing that the function could not get too big—that its maximum value would never exceed some constant value. Put in those terms, the solution to this immensely complicated conjecture, which only a select number of mathematicians understood at the time, seemed like a straightforward enough proposition. But getting that estimate, which would impose a literal and metaphorical ceiling on the function, was not as easy as it sounded.

I was unable to overcome this final obstacle while in New York, but Cheng and I did have success in another area: We found a solution to the higher-dimensional Minkowski equation, the same problem we had made some inroads on earlier in the year. Moser was excited that we had finished this work while at Courant, just as everyone at Courant, it seemed, was enthusiastic about any work of significance that was accomplished there. Moser asked Cheng and me to present our solution at a seminar, which came off well.

I subsequently learned that the Soviet geometer Aleksei Pogorelov had independently solved this problem by a completely different method. His paper came out before ours, but it was printed only in Russian, in a journal that is not widely known, so we hadn’t heard about it. Although our paper was not first, it was not superfluous either because the method we developed was important in itself, apart from the result we had achieved, as it was later used to solve other problems in math.

And going beyond math for a moment (which is usually about as long as I can go), my three to four months in New York were extremely pleasant. I struck up a bit of a friendship at Courant with Eric Bedford, who had just received his PhD in math from Michigan. He showed me how to use the subway system. While we roamed the city, we talked about complex Monge-Ampère equations, which he was working on too, although his methodology was different from the more geometric approach I was following.

I enjoyed my walk every day from my apartment in SoHo through Greenwich Village to Courant. There were always interesting and unexpected things to see. For instance, I went past the same car parked on Spring Street over the course of several days. At first, the vehicle was perfectly intact. But a day later, the tires had been stolen. Over the next couple of days, the body of the car was stripped down more and more. Finally, the rest of the car was gone, only to be replaced by another vehicle that appeared to be in pristine condition, although it was anyone’s guess as to how long that would last.

Little Italy was close to the apartment, and I enjoyed seeing the many festivals that were held there. I spent a lot of my free time with Cheng, his wife, and their baby boy, Bing. When we strolled together through Chinatown and other parts of the city, I often carried Bing (who later became my graduate student at Harvard, earning his PhD in mathematics in 2004). It was nice being so close to Chinatown, not only for the myriad dining possibilities, but also because I liked browsing in the bookstores. And on weekends I went to Princeton to visit Yu-Yun. All in all, my stay in New York proved to be quite convivial.

But in late December, I had to return to California. I flew to Los Angeles with Yu-Yun, who was interviewing with TRW, an aerospace company that has since been subsumed by Northrop Grumman. The interview went well, and the company soon offered her a position.

Yu-Yun went back to Princeton afterwards, and I returned to Stanford where my main research preoccupation, not surprisingly, was still the Calabi conjecture. I sensed that I was close to cracking the problem. The summit was in sight; it was just a matter of getting over that one last obstacle. I felt that if I kept pushing, I would eventually find a way to overcome it.

However, another thing was weighing heavily on my mind. In May 1976, after the spring term at Stanford ended, I visited Yu-Yun at Princeton with a specific goal: I sought, and requested, her hand in marriage—five and a half years after she had made an indelible impression on me in the Berkeley math library. It had been a long haul, and the two of us certainly had our ups and downs. But I’m happy to report that she said yes. We were officially engaged. My brother Stephen came to Princeton from Stony Brook to join us for dinner and celebrate the good news.

Not only had Yu-Yun accepted my proposal, she accepted TRW’s offer as well, which would entail a move to Los Angeles in the near future, given that her job was starting in the fall of 1976. In the hopes of lining up something nearby, I contacted a friend at UCLA, the differential geometer Robert Greene, and told him I’d like to spend the year there. My Sloan Fellowship would cover my salary for the fall quarter, but I was hoping that UCLA would cover the winter and spring quarters if I taught classes. Greene told me that could easily be managed, and in this way I had laid the initial groundwork for our future: Yu-Yun and I would be able to live together and work in the Los Angeles area. She was impressed that I’d been able to arrange this so quickly, given how hard it was to get teaching jobs in those days. And I’m still grateful to Greene for helping to set me up in what proved to be a very hospitable work environment.

I stayed in Princeton until it was time for Yu-Yun to move in early July. We then packed her stuff and set off on a cross-country drive, accompanied by her mother and father. Our first stop was Washington, D.C., where we watched the Fourth of July fireworks during the nation’s two-hundredth (bicentennial) birthday celebration. Along with a million other folks—a sizable fraction of whom appeared intoxicated, boisterously exuding patriotic fervor—we witnessed the pyrotechnics set off over the National Mall. Views of the Washington Monument and Capitol, as a backdrop to the flashing multicolored blazes in the sky, added to the splendor of the scene.

We drove to Boston next to see Yu-Yun’s cousin, whose husband had just died. It was my first visit to that city, and I really liked it. I had no inkling that before long it would become our home for what’s now been more than three decades.

We made another stop in Ithaca, New York, to see another of Yu-Yun’s cousins. From there, we began our cross-country trek in earnest, making it a big sightseeing trip for her parents. We went to Yellowstone National Park and then followed the Rocky Mountains south to the Grand Canyon. Afterwards, we picked up Interstate 40 in Flagstaff, Arizona, and took it all the way to Barstow, California, where we switched to Interstate 15 en route to Los Angeles. The views along the way were stunning, accentuated by the fact that I was in love, eagerly anticipating the married life to come.

Throughout most of the trip, however, my mind quietly wandered toward mathematics. When I was driving, I thought in particular about a classic problem in topology, the Poincaré conjecture, and the fact that no one had yet figured out a good way of approaching it. The original formulation of Poincaré’s problem, which concerns the precise definition of a sphere in topology, had not been solved at that time. The conjecture specifically posits that a “compact,” three-dimensional surface (or manifold)—one that is bounded and finite in extent—is topologically equivalent to a sphere if every loop that can be drawn on that surface can be shrunk down to a point without either tearing the loop or tearing the surface. We call such a surface “simply connected,” which is another way of saying that, unlike a donut, it does not have one or more holes. Using that terminology, the conjecture can be restated as follows: Is any compact, simply connected, three-dimensional surface the same, topologically speaking, as a sphere? While the problem may not sound that intimidating, little progress had been made on this question since it was first raised in 1904.

One might suppose that I would have focused on the Calabi conjecture instead, which was then my main preoccupation, as it had been for many years. I had given that problem much more attention, in part because it is more general, and I sensed it could lead to a large class of manifolds that we didn’t know about. But I always like to have several problems to think about; if I get stuck on one problem, I can turn to something else. And if the problems are of a similar nature, sometimes an idea I get while thinking about one can be applied to the other.

Furthermore, I knew that the zeroth-order estimate of the Calabi conjecture, which I then saw as the lynchpin to the entire problem, would require elaborate calculations with paper and pencil—something I could not attend to, safely or competently, with my hands on the steering wheel. That’s why I picked a more conceptual problem with which to engage the mathematical portion of my brain, and Poincaré’s conundrum served that purpose well. A concrete approach for tackling the problem had yet to be worked out, and perhaps the best thing to do at that stage was to dream about it, which I did—while also trying to keep at least a portion of my mind on the road.

Altogether, we drove more than four thousand miles on our roundabout journey from Princeton to Southern California. And during much of that excursion, my thoughts ineluctably turned to Poincaré’s problem (which I will discuss in some depth in Chapter 11). I didn’t have a great breakthrough, I’m sorry to report, but I was correct in my supposition that geometric analysis could eventually offer a way in.

After arriving in Los Angeles in mid-July, we rented a three-bedroom apartment in Long Beach while we looked for a house. There wasn’t a lot of time, as our wedding was set for early September, and we wanted to be settled in before the big day. We soon found a place in Sepulveda, a former agricultural area in the San Fernando Valley, which was rather far from the ocean. It was a bit of a drive to UCLA too; one could make it in about a half hour, without traffic, but the words “without traffic” and “Los Angeles” can rarely be juxtaposed in the same sentence. It could often take an hour or more, and Yu-Yun had an even longer drive to TRW, which was located in Redondo Beach. It would have been nice to have found something more conveniently situated, but that house—the first I ever purchased—was the only thing we came across that was remotely affordable while also offering some of the amenities we’d been looking for.

We then had a mad scramble, not much more than a month to get the house in order and prepare for the wedding. I drove all over the place looking for used furniture and other essential items, while Yu-Yun attended to her wedding gown and various wedding-related matters. Her parents stayed with us, as did my mother and brother Stephen, both of whom arrived about ten days before the wedding. My mother flew in from Hong Kong, and Stephen came from Harvard, where he had just become a Benjamin Peirce instructor, after having received his PhD in mathematics from Stony Brook a few months before.

The wedding took place on September 4, 1976, followed by a lunch for family and friends. I told Chern I was getting married, thinking he would not come because it was going to be a very modest affair, but he and his wife showed up, which pleased me. My friends Robert Greene and Bruce Bennett came too, as did my mother’s cousin and her husband, who lived in California.

Yu-Yun and I had arranged to go to Catalina Island for our honeymoon, but we had to cancel at the last minute because we underestimated L.A. traffic and missed the ferry. So we went to San Diego instead, where we had a very nice time though also a very brief one, because two days later we had to return to work.

I was happy to get back to my research, which is usually the case, but this time perhaps more than ever because of the commotion in our house with Yu-Yun and me, her parents, and my mother all living under the same roof. I holed up in my study for as long as I could, pouring all of my energy into the Calabi conjecture. Within a week or two, the zeroth-order estimate had been completed and, consequently, the problem as a whole had been completed too. I was relieved and happy, as well as somewhat surprised, because the last few steps had fallen into place more quickly than I had expected.

People have asked me what it felt like to prove the conjecture after having thought about it, off and on, for more than six years. For some strange reason—perhaps influenced by the spirit of my father—my mind turned to an essay written by the Chinese scholar Wang Guowei, who had died about fifty years earlier. Guowei drew on excerpts of classic Chinese poems from the Song Dynasty (960 to 1279) to chart the three stages one typically goes through to achieve success in a major pursuit: First, the narrator scales a high tower, surveying the land in all directions, as far as he can see. He then notes how weak and thin he has become during his lonely quest, though feeling certain that the prize he seeks is well worth the sacrifice. Finally, while searching through a crowd, a thousand times or more, he catches a glimpse of “her”—the object of his pursuit—in the dim and fading light.

These passages summed up rather succinctly—and poetically—the stages I went through in proving the Calabi conjecture. I first needed a good vantage point from which to gain perspective on the problem as a whole. I worked hard—at times to the point of exhaustion, going for long stretches without sufficient food or rest—in pursuit of the quarry at hand. And later, in a fleeting moment of insight, I was able to see my way to the end.

Owing perhaps to my recollection of Guowei’s essay, I also began to think about another famous poem from the Song Dynasty that captured my sentiments after the conclusion of the Calabi proof. The poem depicts a scene in a garden in late spring, sometime long ago: As flower petals drop delicately to the ground, two swallows hover above, flying together in unison. That image resonated with me because solving this mathematics problem had curiously given me a new understanding of and appreciation for nature. By virtue of this work, I felt at one with nature—a sense that was conveyed in the image of two swallows flying as one.

That’s sort of what I was experiencing at an emotional level, but on an intellectual level I wasn’t yet ready to call this a triumph. I had been burned once before with the Calabi conjecture, having assumed three years earlier that I had proved it wrong, only to learn that I’d been mistaken. This time, I didn’t want to take any chances. I checked and rechecked the proof in painstaking detail, going through it four times in four different ways, telling myself that if I got it wrong this time, I would give up mathematics altogether and try my hand at something different—maybe even duck farming. I also sought outside verification. I mailed a copy of the proof to Calabi and made arrangements to follow that up with a visit later in the fall to the University of Pennsylvania.

In the meantime, my UCLA colleague David Gieseker, whom I’d known at IAS, told me about a forthcoming talk in late September by the Harvard algebraic geometer David Mumford. It took me more than two hours to reach the University of California, Irvine, where the seminar was held, but I always think it’s worth hearing what good mathematicians have to say. Mumford focused on a particular “inequality”—a mathematical expression in which one term was less than or greater than the other. The original inequality had been posed about a decade earlier by Antonius van de Ven of Leiden University, but Mumford also mentioned the contributions to this problem made recently by the Russian mathematician Fedor Bogomolov.

At some point during these remarks, I realized I had come across this inequality before—in my early attempts to disprove the Calabi conjecture—and I was pretty sure it could be stated in the exact terms Mumford had specified. I spoke with him after the seminar, telling him I thought I had proved the very point he had raised. I’m pretty sure he didn’t believe me, as I was young and unknown in the world of algebraic geometry. But when I got home, I reviewed my calculations and found that I had used this same inequality during one of my attempts to find a counterexample to the Calabi conjecture. Now that the conjecture had been shown to be true, its corollary—which I had once attempted to disprove in the hopes of establishing a counterexample—must be true as well. That meant I had indeed proved the formulation Mumford spoke of, which is sometimes referred to as the Bogomolov-Miyaoka-Yau inequality. The question as to what happens in the special case when this inequality actually becomes an equality was an open problem, but my method of proof provided a complete determination of the circumstances under which that could occur. This determination in turn led me to the solution of a well-known problem, dating back to the early 1930s, called the Severi conjecture.

I sent a letter to Mumford the next day, laying out my argument. He showed it to his Harvard colleague Phillip Griffiths, and they both agreed that my reasoning was sound. News of these findings spread quickly. At first, people were much more excited about the proofs of the inequality and Severi conjecture than they were about the Calabi proof, even though I insisted that the Calabi conjecture was far more important.

Robert Greene, whose UCLA office was next to mine, appreciated the significance of the latter effort—as did most of the mathematics community in time—and Greene was especially happy I had achieved these results while working at his university. Some algebraic geometers were not thrilled because, in the course of solving two high-profile problems in algebraic geometry, I had not used any of the standard methods of their field. Mumford was different in this regard because he had an open mind, and I believe that’s part of the reason Harvard offered me a job two years later.

This work instantly made me famous, or at least raised my profile, within the math community, and various offers and opportunities started coming my way. The mathematician Isadore Singer contacted me around that time to see whether I might spend a month or so at MIT, starting in November. As I still had the Sloan Fellowship, I was free of teaching duties, so I decided to take Singer up on his offer.

Before going to MIT, I stopped off in Philadelphia to see Calabi and his colleagues, walking them through the proof, step by step. Jerry Kazdan, a mathematician on the Pennsylvania faculty, took detailed notes during my presentation and, to my dismay, shared them with the French mathematician Thierry Aubin without letting me know. Aubin had independently proved a special case of the Calabi conjecture, but with the benefit of the notes provided by Kazdan, he went ahead and claimed credit for a proof of the full conjecture. Kazdan was later kind enough to set the record straight, stating in a published note that he had “learned of Yau’s work during a lecture in December 1976” and subsequently extended that result in a joint paper with Aubin. In this way, Kazdan averted what might otherwise have evolved (or devolved) into an unsavory dispute.

At the conclusion of my meeting with Calabi, he said that everything looked good with respect to my proof. He was, and still is, a superb geometer but didn’t have much expertise when it came to partial differential equations, so he felt it would be worthwhile for us to get together with Nirenberg too. The only time all three of us were free of other work commitments was on Christmas Day, so we agreed to convene in New York City at that time. Calabi claims that was the only time in his life he had a professional obligation on that day, although he happens to be Jewish, as is Nirenberg. I had never celebrated the holiday before, which may be one reason why the three of us were able to arrange a daylong work meeting on Christmas.

After my brief sojourn in Philadelphia, I made my way to Boston, stopping first at Yale in New Haven. Singer, who had invited me to MIT, was quite busy then, having to leave town on personal business for much of the time I was there. As a result, I saw only him once, for dinner, which turned out to be rather consequential. He was working with Michael Atiyah and Nigel Hitchin (my former IAS friend) on special solutions to the equations of C. N. Yang and Robert Mills, which were of fundamental importance to particle physics. Singer felt strongly about the unification of physics and mathematics, and he got me interested in this too. Several years later, in fact, I started working on solutions to the Yang-Mills equations as well. Some papers I did on the subject with Karen Uhlenbeck are considered rather important, and I have to thank Singer for pointing me in this direction.

However, other than that one meal I shared with Singer during my stay at MIT, I was pretty much on my own, as there weren’t too many other geometers around at that time. I was put up in a studio apartment, within walking distance of the school, and spent most of my hours writing up the full Calabi proof, while the snow piled up, rather beautifully, outside my window. Upon finishing this paper, I planned to send it to the Courant publication Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics, out of gratitude to Moser, Nirenberg, and other mathematicians at Courant who’d been so courteous to me. I’d already finished writing a brief announcement of the proof, minus the technical details, which came out in 1977 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The prospects for that manuscript had been enhanced, no doubt, by the fact that it was originally sent to the journal by Chern, an esteemed member of the National Academy.

Harvard, just a mile and a half down the road from MIT, asked me to deliver a series of lectures on the Calabi proof. People at Harvard—including Mumford, Griffiths, and Heisuke Hironaka, as well as the visiting mathematician Andrey Todorov—seemed more curious about the Calabi conjecture than the people I’d met at MIT (except for Singer, who was preoccupied with other pressing matters). So I ended up spending more time at Harvard, and the university even put me up for another month after my month at MIT ended.

I still recall an interesting conversation I had with the algebraic geometer Hironaka (although this occurred at a somewhat later date) about pursuing mathematics in the United States as a person of Asian descent. “It is much easier for Asian Americans to get tenure at a good university in America than at a second-rate university,” said the Japanese-born Hironaka, who won a Fields Medal in 1970 while on the faculty of Harvard. “Because at a second-rate university, where research is not a priority, job advancement is based more on other things like golf.” As someone who has never picked up a golf club in my life, I drew some comfort from those words. For if I truly excelled in my work, I might not have to take up that sport, which was probably never going to be my strong suit.

All told, I enjoyed myself at Harvard and particularly liked the collegiality within the math department. Before I knew it, Christmas was approaching, and I headed to New York for the meeting with Calabi and Nirenberg and my rendezvous with destiny. The snow was coming down hard, and we spent the entire day going through the proof in Nirenberg’s office, taking a break for lunch in Chinatown, which was about the only place we could find restaurants that were open. By the end of the day, my argument was still holding up; no flaws had been uncovered. Calabi and Nirenberg said they would review the manuscript further, but neither they nor anyone else since has found any problems. I published the abbreviated version of the proof in 1977, as mentioned, and the extended version a year later. The argument still stands.

Calabi claimed that the conclusion of our daylong meeting in New York, which yielded a firm consensus that the proof was valid, was the best Christmas present he’d ever received. I could certainly say the same. And I felt that 1976 was ending on a very good note, except for one thing: I missed Yu-Yun badly, after two months away from her. It was time for me to head back to Los Angeles and tend to my marriage under the hopefully forgiving warmth of the Southern California sun.

It might be worth reflecting for a moment on what the proof of the Calabi conjecture accomplished. It showed, for one thing, that nonlinear partial differential equations and geometry could be combined to good effect—a premise that had been driving my research for quite a few years. I also proved the existence, mathematically speaking, of a large class of multidimensional spaces postulated by Calabi—spaces endowed with a combination of distinctive properties that until then had not been considered possible. At the same time, the proof offered not just a solution to the Einstein equations in the case when matter is not present, but the largest class of solutions to those equations that we know of.

Ever since Einstein invented general relativity in 1915, according to the physicist and computer scientist Andrew Hanson, “we have struggled to find manifolds, or ‘Einstein spaces,’ that satisfied his demanding equations. For years, it was hard to find any solutions, yet here, remarkably, was a simple prescription for finding them in any dimension—a long, and possibly infinite, list of manifolds that are absolutely guaranteed to solve Einstein’s equations.”

Sometimes the proof of a theorem marks the end of a chapter. This happened in 1952 when “Hilbert’s Fifth Problem,” which was posed in 1900 by the great mathematician David Hilbert, was finally solved, thanks in large part to the efforts of the Harvard mathematician Andrew Gleason. The solution in that case required feats of great ingenuity, but rather than inspiring new research, it killed off much of the work in that sector of mathematics, leaving other investigators with little to do in the way of follow-through.

From early on, I felt that the Calabi conjecture was different because it would tap into a realm of geometry that was both deep and expansive. The solution to this problem, accordingly, would forge openings into other areas of mathematics that were ripe for exploration. This wasn’t just wishful thinking but rather a consequence, in part, of the unusual way in which I had approached the problem. As you may recall, I first tried to prove the conjecture wrong by providing counterexamples. Given that the conjecture was correct, and had been proved so, all of those attempted counterexamples must, logically speaking, be correct too. In other words, they were theorems in their own right, and my initial announcement of the Calabi proof also unveiled the proofs of five associated theorems in the field of algebraic geometry. The most important of these, as discussed before, was the proof of the Severi conjecture, which had been unsolved for more than four decades. In addition, about a half dozen other problems in algebraic geometry—admittedly of lesser significance—were instantly solved as well. The upshot of this was that a conjecture once considered “too good to be true,” had turned out to be even better than initially supposed.

Yet even that was not the whole story, because deep down, I had a vague though gnawing sense that the Calabi conjecture and its proof would conjoin with physics in an important way, apart from the link with Einstein’s general relativity that I already knew about. I had no clue as to what form this connection might assume, though I still felt certain it was there—or somewhere to be found. Well, it took about eight years for physicists to establish the sort of tie-in with the “Calabi-Yau theorem” that I dreamed of, but it turned out to be well worth the wait.