CHAPTER NINE

Harvard Bound

GOING TO HARVARD IS, in at least one respect, different from going to just another school. I arrived in Cambridge in July 1987 at what the university calls “the oldest institution of higher education in the United States,” and, hokey as it may sound, I could almost feel the weight of history hanging in the air. Owing to the presence of historic buildings within close view of the math department—structures like Massachusetts Hall, built in 1718, and Harvard Hall, built in 1766—there was no mistaking the fact that I was joining a place steeped in tradition, nearly a century and a half older than the United States itself. I was not well versed in Harvard lore upon entering, though I did my best to educate myself about some of my illustrious predecessors.

The “Colledge” was founded in 1636 upon land bequeathed to the school by a local minister, John Harvard, who also donated upon his death the entirety of his four-hundred-volume library (which has since grown into a university-wide collection of roughly seventeen million holdings). Mathematics books did not figure prominently on the shelves of the original library. Nor was mathematics considered an essential part of the school’s early curriculum, as arithmetic and geometry, according to the historian Samuel Eliot Morison, were then regarded “as subjects fit for mechanics, rather than men of learning.”

Algebra was not taught at Harvard until the 1720s or 1730s, roughly a century after the school’s founding. Another century passed before the first bit of original mathematical research was carried out at the college: In 1832, a twenty-three-year-old tutor named Benjamin Peirce published a proof on “perfect numbers”—positive integers, like 6 and 28, that are equal to the sum of their factors (1 + 2 + 3 and 1 + 2 + 4 + 7 + 14). Peirce, however, was not applauded for the achievement, because math faculty members in that era were supposed to focus on teaching and writing textbooks, not on proving theorems.

Things changed dramatically in the early 1890s when two mathematicians trained in Europe, William Fogg Osgood and Maxime Bôcher, became Harvard instructors and eventually full professors. Osgood and Bôcher brought a more “modern” perspective to the school, establishing a research culture within the mathematics department that took hold, gaining considerable momentum by the time I arrived on the scene nearly one hundred years later.

During that century, mathematics had undergone major transformations, and brand-new fields—including category theory, the Langlands program, and geometric analysis—had sprung into existence. Physics, meanwhile, witnessed spectacular advances with the advent of quantum mechanics and general relativity early in the 1900s and, much later, the hope of merging those two successful disciplines into the potentially unifying framework offered by string theory. My interest at the time was squarely focused on string theory, and my friend Isadore Singer, whose office at MIT was just two miles away, was also very excited about the subject. He was well connected too, as I’ve mentioned, and offered to help me get money from the Department of Energy (DOE) so that I could hire some postdocs for research in that area.

Arthur Jaffe, who had just become the Harvard mathematics chair, asked to be written into that proposal, suggesting that we split the money from DOE, if and when it came through. I went along with Jaffe’s request.

DOE insisted that Jaffe and I go to Washington, D.C., to make our funding proposals in person. We were given half an hour for our presentation. Jaffe said that he’d take the first fifteen minutes, and I’d have the last fifteen minutes. His talk went longer than planned, leaving me with just five minutes to make my pitch. But we got the funding, and with it I was able to hire some excellent researchers, including the physicist Brian Greene, who undertook some truly consequential work as my postdoc (see more below).

About a dozen graduate students came with me from San Diego to Boston. Four of them—Jun Li, Wan-Xiong Shi, Gang Tian, and Fangyang Zheng—enrolled at Harvard. I helped get the others placed at nearby schools—Brandeis, MIT, and Northeastern—while I continued to serve as their advisor.

At Harvard, I joined an impressive faculty, and I had tremendous respect for my peers, who included Raoul Bott, Andy Gleason, Dick Gross, Heisuke Hironaka, George Mackey, Barry Mazur, David Mumford, Wilfried Schmid, Shlomo Sternberg, John Tate, Clifford Taubes, and many others. I soon found myself surrounded by a large contingent of students and researchers from China—so many, in fact, that people often assumed that I worked only with Chinese graduate students. But about a third of my PhD students over the years have been non-Chinese, and I’ve always accepted any student who, in my estimation, is good enough to be at Harvard.

Nevertheless, I did have a sizable number of visitors from China—enough to attract the attention of the CIA, which periodically asked me to report on what all these people were up to. The details I provided—concerning Calabi-Yau manifolds, Ricci flow, Yang-Mills theory, and so forth—were sufficiently boring that after I’d submitted several years of these accounts, the CIA stopped asking me. Agency officials had evidently concluded that no national security issues were at stake and that the realm of geometric analysis did not fall under their purview.

Life was busy, as has been the case for as long as I can remember—almost going back to the days when I answered (grudgingly) to the moniker “Little Mushroom.” I had a large number of graduate students to keep occupied as I settled into a new routine at a new university. I finished teaching by 4 p.m. each day so that I could pick up four-year-old Michael at day care and then get six-year-old Isaac at his elementary school in Belmont, where we then lived, one town over from Cambridge. I played with the boys after school and tried to teach them Chinese poems, although those lessons were not a big hit.

I also devoted a lot of attention to my student Tian. He typically came to my house three times a week, working with me a couple of hours each session—a tradition we had started back in San Diego. I trained him hard because I sensed great potential, but my efforts backfired to some extent. I eventually started to wonder whether Tian might be too focused on getting quick results—a tendency that, if borne out, might lead him to take shortcuts. I’ve also found that some people resent the fact that you’ve given them extra help. Rather than being grateful, they turn on you and act as if you’ve done nothing for them, preferring to reinforce the notion that their success was entirely due to their own efforts. It’s similar to what can happen when you loan money to a friend, who then wants nothing further to do with you since your presence reminds him or her of the debt.

But back in 1987, Tian and I were still quite close. He got his PhD in 1988, and I wrote a strong letter of recommendation for him. Princeton offered him a position, though I heard from a mathematician in the department that Siu had aired his concerns about Tian. I wasn’t trying to defy a Harvard colleague, Siu, by means of my avid support of Tian; I was merely trying to help launch my student in his new career, which is a normal thing for an advisor to do.

Nevertheless, I belatedly realized that Siu might have been on to something and that my confidence in Tian was perhaps misplaced. Several years later, Tian told me that he had figured out a way to solve the so-called Yau conjecture, which would have been a very interesting development. (Tian sometimes referred to this as the “Yau-Tian-Donaldson” conjecture to attach his name to the notion, although Donaldson himself called it the “Yau conjecture” because the idea had originated with me.) In a conversation with Singer around that time, I casually mentioned my former graduate student’s accomplishment. Singer—who’d just been named Institute Professor that year, MIT’s most prestigious appointment—was extremely influential on the institute’s faculty. With Singer’s backing, MIT soon offered Tian a faculty position, which he gladly accepted.

By the time Tian joined MIT’s math department in 1995, he still had not written up the paper in question. In fact, he did not post a proof of the full conjecture on the electronic archives until September 2015, twenty years later, and this paper came out eighteen months after a full proof had already been published, electronically, by Xiuxiong Chen, Simon Donaldson, and Song Sun. Looking back now, with the benefit of two decades of hindsight, I wish I’d been more cautious in my conversations with Singer.

The publication of the aforementioned papers did not put the matter to rest because Tian had claimed—in a talk at Stony Brook on October 25, 2012—to have completed the first full proof of the Yau conjecture, which was a problem that Donaldson and his colleagues had been working on for some time, while making significant progress toward that end. About eleven months after that talk, when Tian still had not furnished his proof, Chen, Donaldson, and Sun went public with their grievances, rebutting Tian’s “claims on the grounds of originality, priority and correctness of the mathematical arguments.” Tian’s talk provided “few details,” the group said, and they had seen “no evidence that Tian was in possession of anything approaching a complete proof at the time of his announcement in Stony Brook.” The work that Tian had provided, they added, contained “serious gaps and mistakes,” and many changes and additions subsequently made by Tian “reproduce ideas and techniques that we had previously introduced in our publicly available work.”

Donaldson is an extremely talented mathematician of the highest repute—a true gentleman in the field—and I’m not aware of anyone, including Tian, who has convincingly refuted the charges that he and his colleagues raised.

But we’ve managed to get far ahead of ourselves, so let us return to late 1988 and early 1989, when I was asked to join a National Science Foundation (NSF) panel that was charged with deciding who should get NSF grants in geometry. I served alongside Robert Bryant, Chuu-Lian Terng, and several other mathematicians. As it turned out, I didn’t make many comments throughout this process, partly because of NSF rules that prevent one from evaluating proposals written by one’s colleagues or former students and coauthors. A lot of the people I knew fell into those categories, so I had to leave the room when their proposals were being discussed. When I was able to rejoin the conversations, I was surprised by some of the severe criticisms and what I felt were unduly harsh opinions expressed by other panel members at some of the proposals in question.

Some time after our work was concluded, I ran into Terng at the University of California, Irvine, where she was then teaching. She told me that the NSF would never ask me to join this panel again because my comments regarding the candidates were too disparaging. Her statement surprised me, given that I hadn’t said much compared with other panel members. On the other hand, I realized I had a reputation for being outspoken, sometimes offending people as a result. “Your mere presence,” Terng added, “scared people so much that it kept them from speaking their minds.”

While Terng’s assertion seemed off base to me, she was right about one thing: NSF did not ask me to serve on that geometry panel again. I drew a few lessons from the experience. First, that people can attribute all sorts of motives to you, if they choose to, and you don’t have a lot of say in the matter. And second, that you can sometimes have a big impact, for better or worse, just by sitting in a room—especially if you have the kind of face that some people find inscrutable and perhaps even intimidating.

I applied for U.S. citizenship in 1990. One step in this process involved my taking a test at the Boston Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) office for which I was not adequately prepared. The guy administering the test challenged me with a bunch of questions. For instance, he asked me, “Do you think the U.S. president can declare war without the consent of Congress?” I told him that Congress has to agree, adding that President Nixon had probably cut some corners on that score. The test-giver disagreed with me on the latter point, affirming that Nixon (whatever his faults) had not cut corners on the war declarations front.

Overall, I did well on some questions but not so well on others. The INS officer poked fun at me for my mistakes—a couple of which were, in fact, laughable—but he still passed me on the spot, and my citizenship was granted shortly after that.

Until then, I’d been stateless for a long time. With this new designation of “American citizen,” international travel suddenly became a much simpler proposition for me. But the abrupt change in status left me feeling uneasy. I still had strong emotional ties to China, my place of birth, but no official ties or documentation to that effect. I had even considered becoming a Chinese citizen, although I can’t claim to having devoted much time, or concerted thought, to that proposition. When I mentioned the idea to Qi-Keng Lu, Hua’s former student, he told me that would be a mistake. Lu didn’t offer any further explanation, but I followed his advice and dropped the matter.

Shortly after gaining my new citizenship, Schoen noticed my recently acquired passport while we were traveling together to a conference in Japan. He subsequently nominated me to become a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, and that nomination was upheld by the academy. This was an unexpected “perk” of my new status; Eli Stein, an influential analyst at Princeton, told me I could have been elected to the NAS eight years earlier, right after I received the Fields Medal, had I been a U.S. citizen at that time.

A change occurred at the Journal of Differential Geometry between the November 1989 and January 1990 issues that left Phillip Griffiths off the editorial board. The journal was owned by Lehigh University, and hiring decisions were made by the managing editor, Chuan-Chih Hsiung, a mathematics professor there. I heard through Hsiung that Griffiths was unhappy about losing his editorial position and might have held me partly responsible, even though I had nothing to do with the journal’s personnel moves. Griffiths was a highly visible figure in the world of mathematics—active in the American Mathematical Society and the International Mathematical Union—and not someone you’d go out of your way to antagonize. But it seems that somehow I had unwittingly managed to do just that.

Also on the agenda in 1990 was an AMS Summer Research Institute on Differential Geometry that I was running with Robert Greene and S. Y. Cheng. The three-week event, which was held at UCLA from July 8 to 28, was the biggest summer institute the AMS had ever run, with 426 registered participants and 270 lectures. We decided to dedicate the conference to the celebration of Chern’s seventy-ninth birthday (which was actually his eightieth birthday, according to the Chinese way of accounting, because a newborn there is considered one year old at the time of his or her birth). I proposed the establishment of a medal called the Chern Award—sponsored by the Journal of Differential Geometry—and Chern heartily endorsed the idea. But after I made an announcement about the medal, Chern decided to call the whole thing off. I heard that his sudden change of heart came after consultation with his friends, though no explanation was ever offered to me.

The summer institute, of course, still proceeded without Chern’s presence or the bestowal of an award in his name. I rented a big apartment next to UCLA, which we used for an impromptu family reunion. My sons came, as did my mother. We were joined by my older sister Shing-Yue, my brother Stephen and his son, and my younger sisters Shing-Kay and Shing-Ho, as well as their children. Everything was set up for a large and festive family gathering, with lots of math on the side—almost the perfect combination for me. Except that my mother became gravely ill. We took her for a checkup and, after an extensive battery of tests, a malignancy was found. She was admitted to the hospital the following night. During surgery the next morning, the doctor saw that her cancer was so widespread there was no surgical solution to be had.

Over the next couple of weeks, I went back and forth between the hospital and the conference, where I gave an occasional talk and sat in on various workshops. At the request of many attendees, I also delivered a series of lectures on 100 open problems in geometric analysis—a continuation (with some overlap) of the 120 problems I had discussed in 1979 during the “special year” at IAS.

After the conference was over, I spoke with Harvard’s math chair, Wilfried Schmid, who has always been a great ally to me in the department. Schmid was kind enough to grant me a leave of absence for the fall semester so that I could take care of my mother during chemotherapy and assist her with the array of medical decisions she would soon face. Meanwhile, friends at the California Institute of Technology—including the mathematician Tom Wolff and the physicists John Schwarz and Kip Thorne—helped me secure a Fairchild Fellowship during the fall. Caltech even offered me a nice house on campus, which I turned down in order to stay at my mother’s apartment, where I slept in spartan style on a bamboo floor mat.

For a while, my mother’s cancer seemed to be retreating, and she was doing well. So I went back to Harvard in January 1991 to teach my classes, while Shing-Yue stayed with her. However, by the time I finished classes in May, the cancer had returned, so I immediately went back to California to be with her. We met with her doctor, who delivered the gloomy prognosis that not much more could be done. But there was still a major decision before us: “Do you want to take extraordinary measures to save her if something should happen?” he asked. My mother said no, deciding there would be no point in trying to stave off the inevitable, eking out a little more time at the cost of considerable discomfort. Nevertheless, she was adamant about seeing her grandchildren again, and that wish, fortunately, was granted. I also promised to take care of my sisters and brothers after she was gone.

My mother died on June 2, 1991, at the age of seventy, which is young by today’s standards, although a Chinese saying claims that “a man seldom lives to be seventy years old.” That saying is probably outdated, as life expectancy in the country is now about seventy-six, though she was not able to make it that far.

Fortunately, she was able to thank her friends and relatives for their support and love before she died. And almost her entire immediate family, including her children and grandchildren, made it to her bedside before the final moment came. My mother had been in extreme pain, but she seemed to become more serene after the children arrived. Seeing her sons and daughters, and their sons and daughters, with everyone appearing to be well provided for, put her at ease. Our presence seemed to help her get ready to let go, which she soon did.

We spent a few days arranging for the funeral. My unpleasant uncle who had long ago offered to engage us in the duck-raising business was now living in Oakland, California, but he did not attend the service. His wife made an appearance on his behalf, though she did not express any regrets over my mother’s death. “I did not come earlier,” she explained, “because it is very depressing to see a dying person.” Some etiquette books, I imagine, would frown upon making such a pronouncement at a funeral, but at least she was candid. The rest of us, however, struck a more somber tone. My ten-year-old son Isaac summed up our sentiments in a letter: “Today is a sad, sad day. Laughter has turned to sobs.”

We barely had time for grieving before we had to start thinking about the next steps, such as what to do with our mother’s remains. Ideally, we would have liked for her to be buried next to my father in Hong Kong, but we weren’t sure what would happen if we tried to take my mother’s remains there, which was then moving from British to Chinese rule. We also considered bringing his remains to the United States, but the more I thought about it, the more I realized that my father had no connection to this country. He never learned English and never wanted to come here. So we ended up purchasing a small plot in a Los Angeles cemetery, burying my mother’s remains in an area where many other Chinese people had been laid to rest. Some of our older relatives told us that you should not bury your parents too fast; you’re supposed to wait a couple of weeks. We didn’t know about that arcane rule, and by the time we found out, it was too late anyway.

It was not until all this business was taken care of and things quieted down that I felt the loss of my mother most acutely. I was again wracked with deep sadness, similar to what I’d experienced in the wake of my father’s death, though different this time because both my parents were gone. There was no longer an older generation within the family to defer to; it was now solely upon us to take charge. That was a sobering realization, even if it wasn’t going to change my day-to-day life in an appreciable way.

But I also took stock of my mother’s final years, having deep regrets over the fact that she had worked so hard, taking care of us for most of her life. She gave up almost everything for her family, doing very little to attend to her own needs and happiness. My poor brother Shing-Yuk had needed almost constant attention up until his death not too many years before. I wish my mother had had more time to relax in her old age—to play with her grandchildren, work in her garden, or do anything else that might have brought her peace of mind. Her life was cut short, and she barely had time to rest.

My mother had been a traditional Chinese parent in the sense that she cared more about her sons than her daughters, owing to the conviction that a family’s legacy lies in the hands of its sons. She often told me that she saw my success as her own success, which was part of her extraordinarily selfless philosophy, which was in turn the product of her values and upbringing. While I felt guilty pouring so much time and energy into my career, I knew that it would bring her more pleasure if I did well and accomplished something in the world than if I never distinguished myself. An acute appreciation of the sacrifices my parents made provided me with lasting motivation to throw myself into my work and try to achieve excellence. I didn’t need much of a push in that direction, because—despite some goofing off in my early years—I became quite driven as an adolescent after my father’s death. And I’ve managed to keep up a rather respectable pace ever since.

Some exciting work was, in fact, unfolding at Harvard at the time, with much of the initiative coming from my postdoc Brian Greene. And while my involvement in the early going was rather minimal, this soon grew into a major research avenue for me as well as many others.

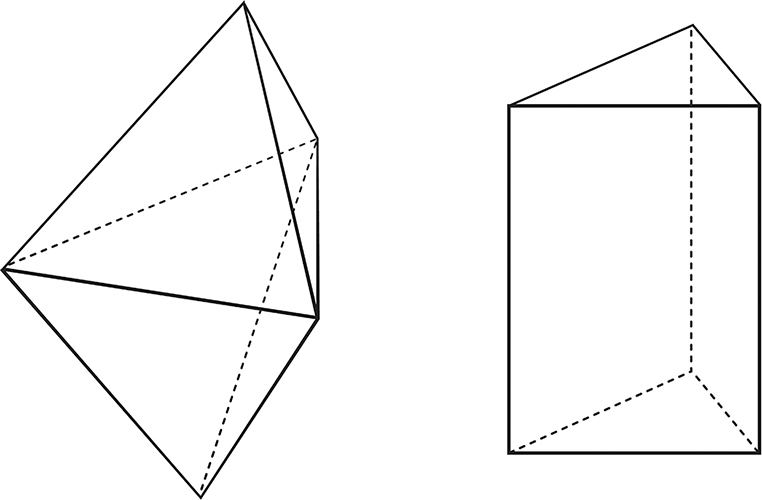

Simple examples of mirror manifolds: the double-tetrahedron (left), which has five vertices and six faces, and the triangular prism (right), which has six vertices and five faces. These rather familiar-looking polyhedra can be used to construct a Calabi-Yau manifold and its mirror pair, with the number of vertices and faces of the constituent polyhedra relating to the internal structure of the associated Calabi-Yau. (Based on original drawings by Xianfeng [David] Gu and Xiaotian [Tim] Yin.)

Shortly after Greene arrived at Harvard, he teamed up with Ronen Plesser, who was then a graduate student of Harvard physicist Cumrun Vafa. Building on prior work by Vafa and other physicists—including Lance Dixon, Doron Gepner, Wolfgang Lerche, and Nicholas Warner—Greene and Plesser started toying around with six-dimensional Calabi-Yau manifolds, which were thought to serve as the shape of the “extra” spatial dimensions in string theory. The duo took one Calabi-Yau shape and rotated it in a very special way, producing a mirror image of sorts—albeit one with a very different shape. They discovered that these two distinct Calabi-Yau shapes shared a hidden kinship, both giving rise to the same physics. Greene and Plesser called this phenomenon “mirror symmetry,” publishing a paper on the subject in 1990. The two Calabi-Yau shapes that yielded identical physics were called “mirror manifolds.”

Mirror symmetry is an example of a “duality”—a phenomenon that comes up rather often in string theory, and in physics more broadly, whereby the same underlying physical situation can be described by two pictures or models that are so different on the surface that they appear to have nothing in common. This idea resonated with me personally because it tied into the notion of yin and yang from ancient Chinese philosophy, and specifically Taoist thought, which stresses the complementarity—and oneness—of two seemingly opposing forces. The concept of duality has led to some remarkable insights in string theory and beyond. Mirror symmetry has been especially productive in this regard.

About a year after Greene and Plesser’s breakthrough, the physicist Philip Candelas of the University of Texas and three collaborators—Paul Green, Xenia de la Ossa, and Linda Parkes—performed an extensive calculation designed to test the concept of mirror symmetry. In the course of this work, Candelas and his colleagues exploited mirror symmetry to solve a century-old problem in “enumerative geometry.” This is a branch of mathematics devoted to counting objects on a geometric space or surface. The problem Candelas and his colleagues specifically took on involves counting the number of curves that can fit onto a so-called quintic threefold—nonsingular versions of which (i.e., those that do not have any holes) comprise probably the simplest six-dimensional Calabi-Yau manifold to be found. The word “quintic” reflects the fact that this space is defined by a polynomial equation of degree five (including terms such as x5 or y5). It’s called a “threefold” because it’s a manifold of three complex—and hence six real—dimensions.

This problem is sometimes referred to as the Schubert problem because in the late 1800s, the German mathematician Hermann Schubert solved its simplest form, counting the number of curves of degree one (or lines) on the quintic. In 1986, the mathematician Sheldon Katz solved a more difficult version of the problem, involving the number of curves of degree two (such as circles) on the quintic. Candelas and colleagues tackled the next order problem, determining the number of curves of degree three (or spheres) that can fit into a quintic.

And here’s how mirror symmetry helped with that task: While the third degree problem was very difficult to solve on the actual quintic, it was much more readily solved on the quintic’s mirror manifold—an object that Greene and Plesser had already constructed. Mirror symmetry, Greene explained, offered a way of “cleverly reorganizing the calculation . . . to make it substantially easier to accomplish.” By doing their calculation on the mirror partner instead of on the original quintic, Candelas’s team was able to obtain a precise answer for the number of curves of degree three: 317,206,375.

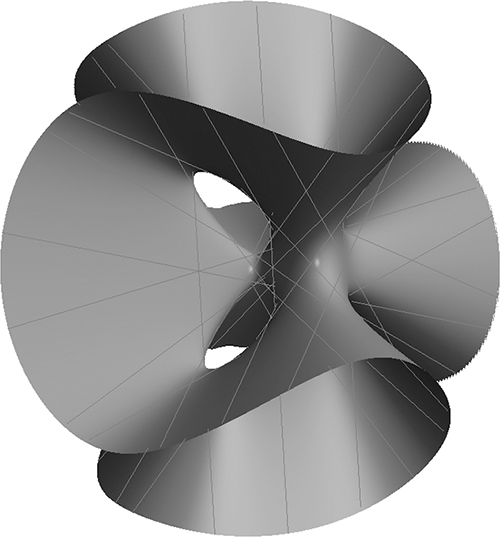

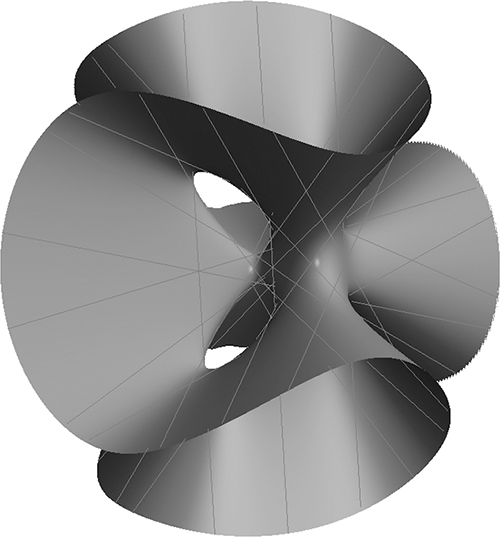

This figure illustrates the general notion of counting curves, or lines, on a surface—albeit on a different surface than those discussed so far. In a celebrated result of nineteenth-century enumerative geometry, the mathematicians Arthur Cayley and George Salmon proved that there are exactly twenty-seven straight lines on a so-called cubic surface, as shown here. Hermann Schubert later generalized this result, which is known as the Cayley-Salmon theorem. (Image courtesy of Richard Palais and the 3D-XplorMath Consortium.)

That certainly got my attention because if their answer was correct, it meant that mirror symmetry might be successfully applied to other problems in enumerative geometry—something that eventually came to pass. Meanwhile, understanding this new concept soon became a top priority for me.

Around the same time, Singer asked whether I would help him run a conference at MSRI on the topic of mathematical physics. Singer’s original idea was to focus on “gauge theory,” which is closely tied to quantum field theory and particle physics, but I suggested a shift in focus, owing to the exciting new developments in mirror symmetry. Singer was somewhat familiar with the subject, having recently attended a talk Brian Greene had given at Harvard. I told him a bit more, and Singer agreed to hold a weeklong session at MSRI on mirror symmetry in May 1991, asking me to serve as chair.

The meeting turned out to be a charged affair because the early work on mirror symmetry—by people like Greene, Plesser, and Candelas—had been carried out by physicists, and mathematicians didn’t yet trust those results and were reluctant to apply them to their own fields like enumerative and algebraic geometry. Such hesitance stems from the fact that deep down, most mathematicians believe they are more rigorous than physicists.

There was already tension in the air at the MSRI meeting when two Norwegian mathematicians, Geir Ellingsrud and Stein Arild Strømme, announced a different result for the third degree Schubert problem, 2,682,549,425, which they had obtained through more conventional mathematical techniques. No one could say for certain as to which answer, if either of them, was correct, but Candelas, Greene, and other mirror symmetry partisans were definitely worried. I went over the calculations with them to see whether anything had gone awry, but we weren’t able to uncover any mistakes. Within about a month, however, Ellingsrud and Strømme found an error in their own calculations. They reworked the numbers, this time getting the same answer as the Candelas team—317,206,375—which provided a strong vote of confidence not only for the notion of mirror symmetry, but for string theory as well.

Candelas’s work had an even broader reach, for he and his colleagues had produced a general formula for solving the quintic threefold problem for not just lines, circles, and spheres but for curves of any and all degrees. That was a bold and sweeping proposition—which had indeed checked out in the case of degrees one, two, and three—but it was still an assertion rather than a proof. In late 1994, Maxim Kontsevich converted this assertion into a precise mathematical statement, which he called the “mirror conjecture.”

Shortly thereafter, I started thinking about proving a version of that conjecture, formulated in somewhat different language. After discussing the problem with my former postdoc Bong Lian and my former PhD student Kefeng Liu, we decided to give it a go. While it was an interesting problem in its own right, I was also motivated by the sense that such a proof could provide mathematical validation for mirror symmetry as a whole.

Our forays in this direction soon ran into a bit of controversy. In a paper posted on the math archives in March 1996, the Berkeley geometer Alexander Givental offered a proof of the mirror conjecture. Lian, Liu, and I went through this paper very carefully, and we were not alone in finding it difficult to follow. That raised questions in our minds as to whether the argument was correct. Those concerns were shared by some mathematicians we spoke with at the time, though others seemed comfortable with Givental’s work.

My colleagues and I asked Givental to clarify some of the steps we found most confusing, but we were still unable to reconstruct the entire argument. So we decided to start afresh, pursuing an independent proof of the mirror conjecture that was published a year later. Some observers called Givental’s paper the first complete proof of the conjecture; others called ours the first complete proof. In an attempt to put the issue to rest, we suggested that the two papers should together constitute proof of the conjecture.

People were certainly free to debate this matter further (and some did), but I was ready to move on, for there was an even bigger question at stake—and a deeper puzzle yet to be solved. The proof of the mirror conjecture put Candelas’s formula on secure footing, showing that the number of curves on the quintic of varying degrees was not random but instead was part of an exquisite mathematical structure—predicated on a phenomenon, mirror symmetry, that had been discovered by physicists. Proof of that conjecture was indeed a significant milestone, providing an independent check that the intuition coming from physics was justified, yet it did little to explain the phenomenon of mirror symmetry itself. That was something I’d already been trying to do, although proceeding on a parallel track.

It started with a conversation I had with Edward Witten at a 1995 mirror symmetry conference in Trieste, Italy, organized by Cumrun Vafa and others. Witten told me about the new “brane theory” that he was developing with Joe Polchinski and others. Branes were special kinds of surfaces of various dimensions—supersymmetric, minimal submanifolds—that were gaining great importance in string theory and other realms of theoretical physics. One reason physicists got interested in branes is that they greatly generalized string theory. A one-dimensional brane, or “one-brane,” is the same as a string, but the theory now had other fundamental ingredients: A two-brane is like a membrane or sheet, a three-brane is like three-dimensional space, and so forth. Thus, researchers had many more building blocks to play with, and the theory became far richer as a result.

Witten discussed some new ideas that the physicists Andy Strominger, Katrin Becker, and Melanie Becker had come up with related to branes, asking me whether these ideas made sense and were natural from the point of view of geometry. I told him that they were natural, realizing a short while afterwards that the mathematicians F. Reese Harvey and Blaine Lawson had essentially hit upon the same ideas earlier, although they had called the objects in question “special Lagrangian cycles” rather than branes.

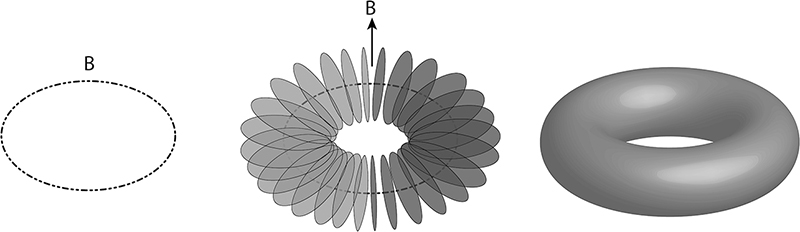

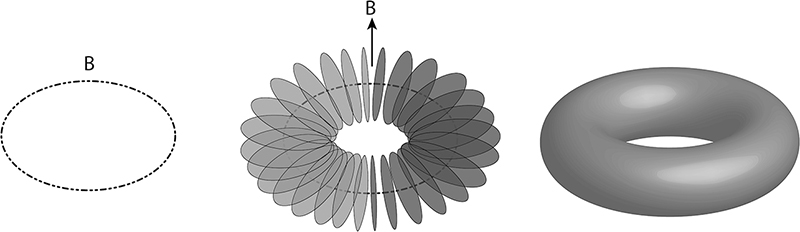

I started thinking about how these submanifolds, or cycles, might relate to the internal structure of Calabi-Yau manifolds in string theory. My postdoc Eric Zaslow and I began working on this shortly after my return to Harvard. We made progress in particular on the question of what the submanifold of a Calabi-Yau manifold would correspond to in the Calabi-Yau’s mirror manifold. We showed, for instance, that a three-dimensional torus, or “donut,” mapped (or corresponded) to a point in the mirror.

Strominger soon came to Harvard to interview for a possible job in the physics department, which he eventually got. The three of us joined forces in an attempt to provide a simple, geometric picture of mirror symmetry. The main premise of the resultant SYZ (Strominger-Yau-Zaslow) conjecture, which emerged from our joint effort, is to show how mirror symmetry comes about and how to create mirror manifolds. The basic approach we came up with is to take a six-dimensional Calabi-Yau manifold and break it down into two three-dimensional submanifolds that are modified in a specific way and then put back together again. At the end of this procedure, if done correctly, one will end up with the mirror manifold of the original Calabi-Yau. The methodology advanced by Strominger, Zaslow, and me helps to illuminate the subtle geometric connection between each mirror pair, thereby offering clues as to how mirror symmetry works. Many people, upon reading our 1996 paper, were surprised by the simplicity of our approach.

Thanks to SYZ, Strominger noted, “mirror symmetry was demystified a little bit. Mathematicians liked it because it provided a geometric picture of where mirror symmetry comes from, and they can use that picture without reference to string theory.”

Two decades after its inception, the SYZ “conjecture”—which has been proved only in special cases and not yet in a general way—has showed remarkable staying power. It remains an active area of study. And if you can believe the University of Michigan mathematician Lizhen Ji, my former PhD student, the conjecture has served as a “guiding principle for a whole generation of people working on mirror symmetry.” Another former student of mine, Conan Leung, continues to turn out fascinating papers on SYZ. Multiple workshops devoted to SYZ and a related topic, “homological mirror symmetry,” are being held each year through a collaboration supported by the Simons Foundation (which was started by Jim Simons), involving an impressive group of players from Harvard, Berkeley, Brandeis, Columbia, Stony Brook, the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Miami, and IHES.

The SYZ conjecture—named after its authors, Andrew Strominger, Shing-Tung Yau, and Eric Zaslow—offers a way of breaking up a complicated space such as a Calabi-Yau manifold into its constituent parts, which are called “submanifolds.” Although we cannot draw a six-dimensional Calabi-Yau, we can draw the only two (real)–dimensional Calabi-Yau, a torus or donut (with a flat metric). The submanifolds that make up the donut are circles, and all of these circles are arranged by a so-called auxiliary space B, which is itself a circle. Each point on B corresponds to a different, smaller circle, and the entire manifold—or donut—consists of the union of those circles. (Based on original drawing by Xianfeng [David] Gu and Xiaotian [Tim] Yin.)

Over the past several years, says my colleague Bong Lian, “the geometric and algebraic pictures of mirror symmetry have started to converge. Progress has been made towards encapsulating this idea [mirror symmetry] within one (albeit complicated) formula.”

Mirror symmetry has had a dramatic, and surprisingly large, influence on enumerative geometry, algebraic geometry, and many other branches of mathematics. Mathematical conferences on mirror symmetry and SYZ are still regularly held all over the world. It’s gratifying to think that this vibrant sector within the math world is an offshoot of string theory and work that was to a large extent originally carried out by my former postdoc Greene and his collaborator Plesser in the late 1980s. Although string theory has not yet proved to be the “theory of everything” that some had hoped for, it has shown its usefulness in mathematics and in many areas of physics. And research in those directions is currently expanding rather than narrowing, which is exciting to consider—as well as to be part of.

Strominger joined the Harvard physics faculty in 1997, and I turned my attention to a series of equations he had drawn up a decade earlier which pertain to more general solutions to string theory that are not limited to Calabi-Yau manifolds. Calabi-Yau manifolds are classified as Kähler, meaning that they are endowed with an internal form of symmetry. Strominger’s equations applied to non-Kähler manifolds, which were largely mysterious. That was part of the appeal for me—to explore something new: A lot of tools had been developed in algebraic geometry for studying Kähler manifolds, but not much methodology was available for dealing with their non-Kähler counterparts, which largely resided in terra incognita.

Another reason I was eager to pursue this work was that mathematics offers one of the best checks we have on string theory. Even though we have not yet devised any definitive experiments to test the theory—and that turns out to be extraordinarily hard to do, owing to the fantastically high energy regimes and vanishingly small distance scales involved—we can at least see whether it’s mathematically consistent. The general approach is to assume something is right and then work out the mathematical consequences. If the consequences you arrive at make sense, then you know the assumption you started with is at least plausible. We still need to see something in nature to know for sure—empirical validation, in other words—but mathematics can provide the first indication that you’re on the right track. And so far, string theory has met the test of mathematical consistency.

Strominger’s equations were difficult to work with, but after wrestling with them for many years I finally found some solutions while working with my former PhD student Jun Li, who was then (and remains) a Stanford professor, and later with Jixiang Fu, a former Harvard postdoc who now teaches at Fudan University in Shanghai.

The work with Fu took many years to bear fruit, but his patience and persistence were finally rewarded. When Chinese scholars come to the United States as postdoctoral researchers, they normally want to rack up as many publications as possible. (This sentiment, I should point out, is not limited to Chinese scholars, as the “publish-or-perish” mentality is pervasive throughout academia—often to the detriment of ambitious and risky undertakings.) Fu and I worked for two years before discovering a mistake in our work. He returned to China with nothing to show for his rather considerable labors; but he came back to Harvard again, and this time we succeeded. He eventually had several important papers in his name and was later asked to give a speech at the International Congress of Mathematicians in Hyderabad, India—all of which helped his career prospects. I am impressed that he stuck it out and am also grateful for his forbearance.

That said, this research is still at an early stage because so far my colleagues and I have managed to solve only special cases of the Strominger equations. My friend Melanie Becker, a string theorist at Texas A&M University, told me that if I were to succeed in my broader goal—solving the Strominger equations in their full generality—that would be an even greater accomplishment than the proof of the Calabi conjecture. Of course, success in this venture, by me or anyone else, is by no means guaranteed. Furthermore, it took a long time to figure out the importance of the Calabi conjecture to mathematics and physics. It could take even longer to determine the full implications of the work on Strominger’s equations, if indeed they are ever realized.

In December 1997, I went to Washington, D.C., with Yu-Yun and our sons to receive a National Medal of Science. Winning a scientific award, as I’ve said, doesn’t really affect my work, nor does it motivate my research agenda in any way, but this particular outing stood out because we got to meet the president of the United States and attend a party in the White House. The most famous winner among our group was James Watson, a codiscoverer of the double helical structure of DNA. My sons had studied biology in school and were excited that Watson would be there. We’d all read The Double Helix, and I liked the book because Watson seemed so honest, although I didn’t appreciate the fact that he seemed so comfortable with the idea that he and Francis Crick had taken some of the credit that should rightfully have gone to Rosalind Franklin. That was nothing to be proud of, even if the work, overall, was monumental.

During the White House party, I met Robert Weinberg, a well-known cancer researcher from MIT, and my wife and I chatted briefly with him and his wife. He asked me what I thought about math education, and I told him that I thought math education was very important, though the field suffered because, as I said, “Most of the people in it study only math education; they don’t study math.” Weinberg then replied, “Professor Yau, my wife is in math education.” At that point our conversation got a bit strained.

Before President Bill Clinton came out and spoke, Vice President Al Gore handed each of the winners a certificate. I mentioned something to Gore about his being a Harvard graduate and my being a Harvard professor, but he must not have heard what I said, or perhaps he could not understand my words, as he made no reply. We then waited a long time for Clinton to arrive. Some folks were getting impatient, but when he finally appeared, he was extremely charming and needed to say no more than a sentence or two to make everyone happy. I guess that’s what they call charisma, and Clinton—despite some apparent lapses in judgment and behavior—seemed to have no shortage of that.

This award was different from others I’d won, such as the Fields Medal, which almost no one outside of mathematics knows about. The National Medal of Science, by contrast, makes a bit of news. My sons used to think I was the most boring person on Earth and that the work I did couldn’t have been more tedious, but they were impressed to see me in the company of celebrities they’d actually heard of, let alone the president of the United States. “Ba always acts like he’s smart,” my son Isaac had said, although up until then he hadn’t seen much evidence of that. But he now had to reassess and told his brother Michael, “Maybe he is actually good.”

My neighbors in Belmont, who hadn’t given me a moment’s notice before, suddenly learned something about me through local news stories that reported on the prize. I wasn’t just some Chinese guy who was hard to understand and generally kept to himself. I might in fact be someone worth paying attention to. Like many people from China, I never fit well into the U.S. suburban scene. I didn’t play tennis or golf; I didn’t coach soccer or Little League baseball; and I didn’t find many opportunities to interact with my neighbors. Although I lived next to them, I also lived a world apart. This award didn’t change that, but at least some of the people around me had a better sense of who I was and realized for the first time that I was at least somewhat accomplished.

My sons often complained that they, like me, didn’t fit in well either, though I tried hard to get them involved in all kinds of “normal” American things. I took them to places like Disney World, SeaWorld, and the San Diego Zoo. I took them to movies at the Fresh Pond Cinema in Cambridge and to the local video store where they rented scores of popular films. I also carted them all over town so they could practice, and compete in, swimming, soccer, basketball, and other sports. I even took them skiing; I would sit in a drafty lodge all day long doing mathematics while they hit the slopes. Michael once complained that no kids came to our house because we didn’t have any fun games. So we went to the store together and spent hundreds of dollars on foosball, table hockey, and other ostensible forms of amusement, but that still didn’t draw many kids to our house.

Nevertheless, my sons garnered some attention in high school through their prowess in science. Harvard biologist and immunologist Jack Strominger, my friend Andy’s father, allowed both of my boys to work in his laboratory, which was something he did not normally do for high school students. I didn’t push them toward mathematics because I felt that might put too much pressure on them, given that I was by then a known commodity in the field. The MIT algebraic geometer Michael Artin was often compared to his famous father, Emil Artin, and the same thing happened to the Harvard mathematician Garrett Birkhoff, whose father, George David Birkhoff, was one of the most influential mathematicians of his generation. That’s not always the easiest situation to be in, especially for someone starting out in a career.

I thought my boys might benefit from trying their hand in another branch of science, and they both seemed to have an affinity for biology. Isaac and Michael parlayed research projects they undertook in Strominger’s lab into entries in the nationwide Intel Science Talent Search. Isaac was a semifinalist in the competition.

Three years later, Michael also took a job in Strominger’s lab—after first working at a Gap clothing store in downtown Belmont and discovering that full-time employment can be taxing (although his wardrobe benefited). Michael was initially charged with cleaning Strominger’s lab, but he persuaded a postdoc with whom he’d become friendly to help him carry out some experiments on the side. His research project turned out well, and he refashioned it into an entry for the Intel competition, where he became a finalist. That triumph in turn instantly boosted his popularity at high school, and even some girls started to take an interest.

I was grateful to receive a letter from the Talent Search saying that Michael had named me as “the one person who has been most influential in the development of my scientific career.” Although my father was not a mathematician, he was the one who inspired me most of all to become a mathematician, and my mother was the person who did more than anyone else to support me until I could realize that goal. I was glad that I’d been able to fulfill a similar role for my sons. After majoring in biology at Harvard, Michael went on to earn an MD from Stanford Medical School. Isaac got a PhD from Harvard Medical School, where he now teaches microbiology and immunology.

While “honor thy father” is a basic dictum in Chinese culture, I’m acutely aware of the fact that my wife, who’s had a long career in physics, has had an equally big role, if not bigger, in teaching our children and cultivating their interest in science. It’s truly been a team effort in our case, and Yu-Yun and I were pleased that our sons fared well in the American educational system.

At the same time, we had concerns that we might have gone too far in trying to afford them a lifestyle that was similar to that of their peers in terms of recreational activities, entertainment, and the like. The process of “Americanization” had apparently come at a price, as they seemed to be losing their awareness and appreciation of their Chinese heritage. Led by Michael, the boys started to resist their Chinese language studies. What was needed, we realized, was a countervailing strategy to offset this disturbing trend and help reacquaint them with their native roots.