1

CHANNELING THE URGE: THE FIRST SEX LAWS

FOR A FOUR-THOUSAND-YEAR-OLD Mesopotamian homicide case, the record is impressively intact. Decades of archaeological excavations have yielded multiple copies describing the case in detail, spelled out on broken clay tablets embossed with cuneiform writing. The duplication makes sense, given that the victim was Lu-Inanna, a high priest of Enlil—one of this civilization’s most important gods—and that the murder took place in Nippur, a holy city. By the time the trial came up, Nippur had been continuously inhabited for thousands of years.

The charge was murder, although sex was all over the case. The accused were two freedmen, a male slave, and Lu-Inanna’s widow, Nin-Dada. Given the severity of the crime and the high status of the victim, the case was taken first to the king in nearby Isin. He took a good look, and then assigned it to the nine-member Assembly of Nippur.

By the time the case reached the assembly, no one doubted that Lu-Inanna had been killed by the three male suspects, nor was there any question that they had told Nin-Dada what they had done. The key remaining issue was why Nin-Dada had not immediately given up the killers to the authorities. Rather, the record says, she “opened not her mouth, covered it up.” Had she participated in the murder? If so, her execution—most likely by impalement—was a certainty. If she had not, then what crime had she committed by keeping her mouth shut?

First, a little law. It was forbidden in Mesopotamia not to report another person’s misconduct, especially when sex was involved. (It was no different in nearby Assyria, where, for instance, prostitutes were not allowed to wear veils: If a man observed a prostitute wearing a veil and said nothing, he would be whipped, have a cord forcibly run through his ears like a horse’s bridle, and then be led around town to be ridiculed.) Mesopotamian barmaids were required to eavesdrop on their criminal customers as they drank. If the barmaids heard something incriminating and failed to report it, they could be put to death. Adultery, at least when committed by women, was also punished harshly. A disloyal wife who had plotted against her husband was treated worst of all, by being stuck on a long pole and left to suffer a slow and very public death.

There was no proof that Nin-Dada had ever had sex with any of the killers, or that she had taken part in her husband’s murder. Had she been well represented before the assembly, she might have squeaked through the trial with her life. Her supposed advocates could not have done a worse job, however. They presented a “weak female” defense, arguing that Nin-Dada was so helpless and easily intimidated that she had had no choice but to remain mute. As if that argument were not a sure enough loser, her defenders went even further, claiming that even if she had participated in the murder, she still would have been innocent because “as a woman . . . what could she do?”

Even after four millennia and translation from a long-dead language, the anger in the assembly’s response rises from the tablets like heat:

A woman who values not her husband might know his enemy . . . He might kill her husband. He might then inform her that her husband has been killed. Is it she who [as good as] killed her husband. Her guilt exceeds even that of those who [actually] kill a man.

The Sumerian verb for “to know” meant the same as “to have sex,” and Nin-Dada’s silence after her husband’s murder was enough for the assembly to conclude that she was hungry for such knowledge. Far from seeing her as a weakling, the assembly made clear that she should have braved any intimidation to see that the murder was avenged. Nin-Dada was sentenced to die.

So go the brief lives and unnatural deaths of a Mesopotamian husband and wife, he murdered for unknown reasons and she for disrespecting her husband’s memory. They inhabited a world unknown to most of us, and barely understood by specialists at that.

1

WITH THE CASE of Nin-Dada, this chapter’s inquiry into ancient sex law begins at the time of the first known human writing. Although I shall touch on earlier periods, the absence of documentation makes the journey hazardous. In 1991, for example, hikers found a frozen five-thousand-year-old man in the Italian Alps. He had fifty-seven tattoos, still wore snowshoes, and carried a copper axe that appeared to have been of little use to him in his final moments. He was killed in some kind of violent confrontation. The corpse, now known as Ötzi the Iceman, also appeared at first not to have had a penis, which caused no end of questions (the penis was later found, looking much the worse for wear). Was he ritually mutilated, or castrated by a jealous husband? Or did his genitals, so cold and lifeless for several millennia, just shrivel away? Without additional information—that is, something we can read—it is impossible to tell whether he died at the hands of the law or whether sex had anything to do with his fate. While Ötzi is a relatively recent ancestor of ours, we do not know enough to arrive at any conclusions about the sexual mores according to which he and his tattoo-loving neighbors lived.

This chapter will draw on cases from as far west as Egypt, across Turkey and the Eurasian landmass, to what is now Iran. Its main focus will be Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), as well as the land that now comprises Israel and the Palestinian territories. This vast region has hosted urban civilizations as complex as those of Rome, Greece, and various caliphates down to the Ottoman Empire, and as elementary as tiny bands of nomadic hunters. Its peoples spoke a multitude of languages and dialects, most of them now lost. These Sumerians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Hittites, Hebrews, and Egyptians were slaves and freemen, priests and prisoners, whores and kings, gods and witches. They mixed, intermarried, and raped each other. Everyone had a role to play in their respective societies, and was subject to punishment for bad conduct—especially when it concerned sex. Sex for some was blessed, and for others, grounds for impalement.

All ancient civilizations were intent on controlling people’s sex lives. The oldest extant written law, which hails from the early Sumerian kingdom of Ur-Nammu (circa 2100 BC), devoted quite a bit of attention to sexual matters. One of the earliest capital punishment laws on record anywhere concerned adultery. Ur-Nammu’s Law No. 7 mandated that married women who seduced other men were to be killed; their lovers were to be let off scot-free. Death awaited virtually every other straying wife in the Near East, while the fates of their lovers were often left to the husbands to decide.

The first legal codes, such as that of Ur-Nammu, were founded on the customs of earlier precarious times. Even after small groups coalesced into identifiable societies, towns faced constant threat by bands of marauders looking to exploit any opportunity to invade and pillage. Adultery risked destabilizing the unity and bloodlines of a family, rendering an entire tribe or settlement that much more vulnerable. Ur-Nammu’s death penalty for adulterous women was, in this light, no innovation; it was simply the first such punishment we know about that was written down.

Ancient societies influenced each other, and the laws of one group often were adopted by its enemies and then developed further. As centuries passed, for example, the elementary sexual prohibitions of Sumerian kingdoms like Ur-Nammu evolved into the obsessively detailed rules of the Hebrews, which in turn became the foundation for the sex laws of the church and every Christian state. Until recently, the Old Testament was believed to contain the world’s first written laws. How could it be otherwise, when the Torah (the first five books of the Bible) was said to have been issued to Moses directly from God, on a mountain, amid thunder? As a product of divine revelation, the Bible could then have no predecessor, at least not one written by human beings. The 613 rules set out in the Torah were supposedly written by the same “hand” that molded the universe, and to say that the Bible drew from other societies in the Near East was to imply that God looked to pagan kings for advice.

The Hebrew claim of precedence was shattered in 1902, when French archaeologists found several large black stones in ancient Susa, Iran, which bore carved cuneiform text. When reassembled, the stones formed a single stele more than eight feet high. The writing, it was later proved, consisted of the Babylonian king Hammurabi’s 282 laws, a highly sophisticated comprehensive legal code. The stele itself was carved around 1790 BC. Further investigation revealed that the Code of Hammurabi not only predated Moses and the Torah by at least five centuries, it also dominated Near Eastern law for at least fifteen hundred years. Like Moses, moreover, Hammurabi was merely the messenger: The stele bore the declaration that the king’s laws also originated from heaven.

Several other legal codes have since been discovered (including that of Ur-Nammu), which were set down long before Hammurabi’s own time. Many of the Bible’s sex laws now look more like knockoffs of earlier regional laws than the original word of God. For example, one law, protecting men’s testicles, from Deuteronomy 25:11–12, reads:

If two men . . . are struggling together, and the wife of one comes near to deliver her husband from the hand of the one who is striking him, and puts out her hand and seizes his genitals, then you shall cut off her hand; you shall not show pity.

Did that rule really come from on high? The Hebrews might have wished to believe that Deuteronomy was the revelation of Jehovah, but the truth is much more prosaic: It was likely borrowed from the neighboring Assyrians. The laws of Middle Assyria, which date from 1450 to 1250 BC, show similar concern for testicles and an equal readiness to punish women who hurt them:

If a woman in a quarrel injures the testicle of a man, one of her fingers they shall cut off. And if a physician bind it up and the other testicle which is beside it be infected thereby, or take harm; or in a quarrel she injure the other testicle, they shall destroy both of her eyes.

The similarity of these laws is evident, though the Assyrians were no friends of the Hebrews—they conquered the Kingdom of Israel in 722 BC and exiled its inhabitants. Assuming the Torah was in fact composed by men and not dictated to Moses by the Creator of the universe, it appears that this Hebrew law was a reflection of a regional testicle fixation. There are multiple other instances of Hebrew laws overlapping with the laws of their enemies. For example, section 117 of Hammurabi’s Code holds that a man can put his family members into service as slaves in order to pay a debt, but only for three years. A nearly identical Hebrew law permits such enslavement for up to six years.

Western sex law, whether via Assyrian testicles or Hebrew whorehouses, was thus created by ancient peoples who legitimized their rules by claiming that they originated in heaven. It is easiest to work with written records such as the cuneiform tablets in Nin-Dada’s trial, but doing so can prove deceptive as well. If it could be shown that other trials had taken place in the Assembly of Nippur on similar grounds, in which the widows were let off without punishment, we would not then be able to draw the same conclusions about Babylonian society. It stands to reason that there were many, perhaps thousands, of sex trials, the records of which have been lost to history. We are forced to work only with what we have discovered, and what we are able to decipher.

There is little to be learned by separating documented ancient history from

prehistory. No ceremony, solar eclipse, visit from angels, or resetting of calendars marked the “start” of history. No one, presumably, knew or cared whether the stories of their lives were being preserved for people who would remain unborn for another four millennia. Nor was there a sudden change in morality; when people first wrote down their laws, the prehistoric mind-set was still in place. The written laws of Ur-Nammu, Hammurabi, and Moses reflected the crosscurrents of long-established, illiterate societies.

2

BLOOD RELATIONS AND BLOODY RELATIONS: THE FIRST SEX CRIMES

Early law thus emerged from prehistoric traditions. There is a lot of guesswork involved in determining exactly what these traditions comprised, but we can be certain that sexual impulses themselves would have been as urgently experienced then as they are today, driving people to do things with their bodies for which they were punished. For Saint Augustine, the insistent demands of the genitals were God’s curse on humanity for the sins of Adam and Eve; every sex act and thought was a new penalty for the wrongs of the first man and woman. Coming at the same subject from a different perspective, Plato also recognized humanity’s intense craving for sex, saying in his last dialogue, The Laws, that it “influences the souls of men with the most raging frenzy—the lust for the sowing of offspring that burns with the utmost violence.” For Plato, the sex drive was a mad subconscious effort to reunify humanity’s fractured nature.

Early peoples did not characterize the sex urge in those words, but they certainly felt it. They surely recognized that something had to be done to corral the “frenzy” if people were to live together in large groups. Until the sexual impulse was tamed and subordinated to common needs, civilized life would be impossible. For men, that meant trying to reconcile themselves to the mystery of the female. In primitive societies, men presumably regarded women with the same awe and terror they felt toward the natural world. Early humankind was at perennial war with nature, the forces of which were lethal as well as incomprehensible. The core of the natural world was the female womb, from which newborn human life tumbled out in a gush of blood and screams.

It was not until about 9000 BC (roughly one hundred and eighty-five thousand years after the advent of Homo sapiens sapiens, or modern humans) that the link between sexual intercourse and pregnancy was confirmed. Until then, sex and childbirth were likely too far separated in time for people to make the connection, and in any event, women spent much of their short adult lives either pregnant or lactating. Children seemed to just appear in the womb. Even more incomprehensible, and perhaps horrifying, was the blood that periodically flowed from women’s bodies. Blood was life itself, magical and dangerous to lose, yet women bled freely for days at a time with no injury, and no one knew why. The one clear fact was that menstrual blood came from women only, and from the same place where human life began.

The first sexual prohibitions could well have taken the form of Paleolithic taboos against intercourse with women during their periods. (Such rules still exist in many cultures, grounded on the supposed “unclean” nature of menstruation.) These proscriptions would have had much deeper foundations than mere hygiene, however—perhaps the sudden appearance of menstrual blood reminded men that, despite their superior physical strength, they could not generate human life on their own. Perhaps menstrual blood was considered a sign of female shame or even infertility, as women only bled when they were not pregnant or lactating. Most likely, the rejection of women while their blood flowed was a precautionary move, a way to appease the threatening divine presence men felt when confronted with the unknown.

By barring sex during specific times of the month, primitive societies could impose order onto the chaos of sex and reproduction. As time passed, men’s fear of women often evolved into outright hostility, to the effect that menstruating women were regarded as equal parts dangerous and filthy. The belief was amplified in later centuries, in various cultures. To ancient Hindus, menstruation was a zero-sum game: Sex with women during their periods was thought to sap the “strength, the might and the vitality” of men, while avoiding sexual relations with menstruating women was believed to add to men’s wisdom and vitality. In Babylon, everything a woman touched during her period, from furniture to people, was considered contaminated, and to the later Assyrians the very word “menstruation” was synonymous with “unapproachable.”

3No one took menstrual fear further into the realm of obsession than the Hebrews. The Torah, which decrees that women and everything they touch are unclean during their periods, also pronounces that this contamination extends to things touched by people who are themselves touched by menstruating women. For example, if a man “lies” with a woman during her period and later sleeps on another bed, that bed becomes unclean. The Bible also requires that at the conclusion of a woman’s period, she is to bring two turtledoves or pigeons to a priest for sacrifice. Until the birds were slaughtered, she would be separated from everyone in her community, including her husband. In any event, women were not to be touched for seven days following the beginning of their periods, regardless of when the bleeding stopped. Later versions of Jewish law pronounced women “unclean” for about half the month, requiring them to take ritual baths before returning to their husbands’ beds and mandating that wives test themselves for blood with rags before having sex. Violations of these laws subjected the man and the woman to arrest and, at least in theory, the death penalty.

Over the centuries, menstrual blood found its way into recipes for sex potions as a key ingredient. In several European cultures during the Middle Ages, mothers collected their daughters’ first menstrual flows, saving them and later mixing them into aphrodisiacs to spark desire in their sons-in-law. In fifteenth-century Venice, a lower-class girl used a mixture of her own menstrual blood, a rooster heart, wine, and flour to make a young aristocratic man “insane” with love for her. She was put to death; the young man was viewed by the court as an unwitting victim. As late as 1878,

The British Medical Journal ran extensive correspondence on the question of whether or not a ham could turn rancid at the touch of a menstruating woman.

4

ANOTHER PREHISTORIC SEXUAL taboo, which probably led to the first formal law of any kind, banned incest. While few would disagree that sex within families is repulsive, the rule against it is not so simple. For most of human existence until relatively recently, there were no cities or towns, and very few people. Life was lived in tiny groups, and while interbreeding between tribes did occur, bands of several dozen people might live for extended periods without ever seeing any other human beings. Reproduction between close relatives must have occurred all the time. Nevertheless, without prohibitions against close inbreeding, human DNA would never have acquired the strength to adapt to the climatic and other challenges faced by our ancestors. The formation of cross-tribal societies about fifty thousand years ago allowed people to “outbreed,” diversifying their genetic makeup and making possible the most recent stages of human evolution.

Anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss regarded the incest taboo as a critical element of “culture itself,” and much of ancient history backs him up. The Babylonians treated incest as a source of contagion and punished it with banishment, drowning, or burning. Once the deed was done, the pollution had to be cleansed regardless of whether or not either of the participants was at fault. A mother raped by her son, for instance, would burn to death right alongside him. The fact that she was taken by force meant nothing; for the sake of everyone and to appease the gods, she had to die. The Hittites and Assyrians also considered incest an abomination punishable by death, as did their neighbors the Hebrews and most every other society since then. Even monkeys avoid it.

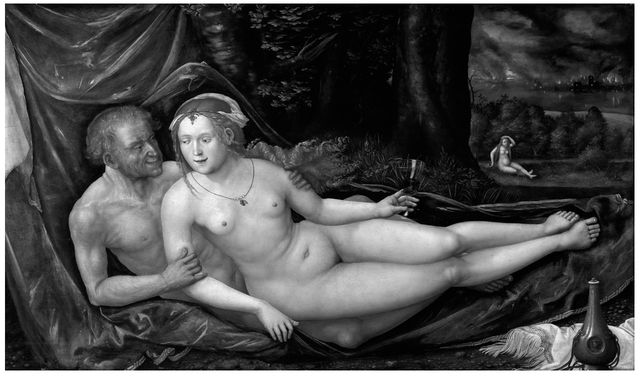

Thus incest appears to be not only the first, but also the one universal, “natural” sexual taboo. If that were the case, though, no one told the peoples of ancient Hawaii, Peru, Mexico, and especially Egypt and Persia. For the ancient Egyptians, incest was not only a natural aspect of human life, it was also the key event in one of their most sacred and enduring creation myths: that of Isis, the mother-whore-goddess who divided earth from heaven and assigned languages to nations. Isis married her brother, the sun god Osiris, whom she adored even when they were still in their mother’s womb. Their perfect union was shattered when Osiris was murdered by his brother Set, god of darkness. Set cut Osiris into pieces, which he flung all over Egypt. Bereft, Isis searched for her beloved everywhere. She managed to retrieve every part of him except the most important one, the engine of their sacred union—his penis. Nevertheless, she resuscitated him and, with the help of a replica of his genitals, the reunited lovers produced a child, Horus. This tale, told in countless versions throughout the Mediterranean, made Isis a holy and deeply resonant symbol of renewal and immortality. During celebrations, Osiris was represented as a giant phallus.

Egyptian pharaohs often married their sisters, half sisters, and daughters, especially during the Eighteenth Dynasty (1570–1397 BC). The idea was to exclude outsiders from the bloodline, and ensure that the bounty of conquest would not be shared with in-laws. Sometimes, as in the families of the pharaohs Seqenenre Tao II and Ahhotep I, royal daughters were only allowed to marry their fathers. However, the same restrictions never bound the pharaohs themselves: They kept a supply of secondary queens at hand with whom to have children. New kings were usually mothered by nonroyal women, which sometimes made family lines quite complicated.

Egyptian incest was not restricted to the society’s upper crust; the practice was adopted by the lower orders, and became common among people of all ranks. At the time of the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC, sisters typically married their full or half brothers or their fathers. In the cities, one-third of all young men with marriageable sisters married them, doing away with any need to find a bride from outside the family. (In Arsinoe, virtually every man with a living younger sister married her.) The Romans shared none of the Egyptians’ incestuous customs, and worked hard to suppress them—after about three centuries, they succeeded.

In ancient Persia, marriage within immediate families was seen as a blessed thing. Under Zoroastrianism, which came into being sometime between the second millennium and sixth century BC, royal, priestly, and common families all practiced incest. Such unions were praised in legal and religious texts as “perfect” acts that brought great rewards in heaven and wiped away nearly all sins. Said one ancient source:

[B]lessed is he who has a child of his child . . . pleasure, sweetness and joy are owing to a son that begets from a daughter of his own, who is also a brother of that same mother, and he who is born of a son and a mother is also a brother of that same father; this is a much greater pleasure, which is a blessing of the joy . . . the family is more perfect; its nature is without vexation and gathering affection.

For the Persians, a sexual union within a family was so sanctified that the fluids produced by an incestuous couple were thought to have curative powers. A passage from the Vendidad, a collection of Zoroastrian holy texts, advises corpse-bearers that they may purify themselves with the mingled urine of a closely related married couple. Conversely, any reluctance on a man’s part to marry his sister or mother was considered a grave sin deserving of “damnation in the highest degree,” even if he troubled to find his intended bride another husband. Women who refused to marry their relatives fared even worse: In one Zoroastrian text, a visitor to hell finds a woman condemned to suffer the pain of having a snake crawl in and out of her mouth for eternity. The visitor is told: “This is the soul of that wicked woman who violated next-of-kin marriage.”

Like the Egyptians, the Persians used intrafamily marriages to hoard property, but that only partly explains why such unions—so rare in the ancient and modern worlds alike—were venerated. A full understanding requires a greater degree of probing into the religious practices of these societies than this book permits, but the key point is that there are in fact no “eternal” or “natural” sex laws. What is contrary to nature for one group can be a blessing for others. The Egyptians and Persians were not nomads or cave dwellers who had no choice but to reproduce within close family groups. Theirs were two of humanity’s longest-lasting civilizations. Lévi-Strauss was surely wrong, then, to claim that the ban against incest is culture itself. Like homosexuality, fellatio, and dozens of other sex acts that have been condemned as both unnatural and against God’s will, intrafamily sex was a matter of choice.

Taboos against incest and sex during menstruation have evolved in nearly opposite directions. Bans against sexual contact with women during their periods persist in some religious contexts, but have been ignored by secular law. The Talmud requires flogging for such things, but no modern Western government has given the subject any attention. Incest, however, remains a “universal taboo” and is a crime almost everywhere. It is a felony in nearly every American state, punishable by prison terms of up to twenty years. In Utah, a five-year prison sentence awaits anyone having sex even with a “half” first cousin. Many states also mandate punishments even when the incestuous sex is forced, or when, as with sexual relations between step- and adoptive relations, there is no risk of genetic harm. It is enough that such relations resemble sex within the same blood family for the offenders to be removed from society.

5

VIRGIN TERRITORY

Female virginity was a commodity in the ancient world, with a price, a market, and laws to protect its male owners. Ancient Egyptians had little concern with a woman’s virginity at marriage, but that was atypical. Virtually everywhere else, “a maiden who has never stripped off her clothes in her husband’s lap” or, somewhat less graphically, a woman who “has not known a man” was precious indeed—or at least her maidenhead was. The right to deflower a girl belonged to her husband and no one else, and anyone interfering with it was severely punished.

During Ur-Nammu’s reign, a man who raped a betrothed virgin was put to death. The punishment did not address the violence committed against the girl, but rather the theft of the intended bridegroom’s opportunity to be the first to have her. By the time of the Assyrians, more than a thousand years later, the laws were more intricate and, in keeping with Assyrian tradition, more vicious. Rapists of betrothed girls were killed as they always had been, but the law now also turned its attention to the rape of females who had not yet been promised in marriage. In such cases, compensation was due to a father for his lost chance at marrying his daughter off at the high price virgins commanded. He could sue the rapist and collect three times his virgin daughter’s marriage value, and then either force the rapist to marry the girl or keep her to sell off to someone else. A sullied girl would fetch a smaller bride-price on the open market, but the father still came out ahead. To add a dollop of sweet revenge to the deal, Assyrian fathers in such cases also had the option of taking a rapist’s wife as a slave to rape and abuse as often as he wished. Thus two innocent women might suffer when a man raped a virgin girl: the victim herself, who might be forced by her father to spend the rest of her life with the man who attacked her, and the rapist’s wife, who might be delivered into the vicious embrace of the victim’s family.

An Assyrian father could cash in on his daughter’s lost virginity even when she gave it away willingly. In that case, the girl’s lover would still owe the father three times her marriage value, but he would not be required to serve up his own wife for abuse. Rather, the father was encouraged to take out his anger on his daughter: “The father shall treat his daughter in whatever manner he chooses.” This sentence was perhaps legal overkill, as there were no restraints on what a father could do to his children. In any event, women were no better treated after they were married. The law was clear that a husband could punish his wife by whipping and hitting her, pulling her hair, and mutilating her ears.

The Torah tracks the Assyrian system of compensating fathers for their daughters’ lost virginity. As everywhere else in the Near East, respectable Hebrew girls had no right to choose their sex partners. Only prostitutes could do that. If a virgin girl decided to have sex with a man anyway, that choice was made permanent: Any man who slept with such a maiden was required to pay the girl’s bride-price (that is, her price as a virgin) to her father, then marry her. As with the Assyrians, the father was also allowed to take the money and marry his daughter off to someone else, presumably for a lower price. The thinking changed somewhat if the maiden had been taken by force. In that case, the man was bound to pay the father a larger sum of money and then marry the girl without the possibility of ever divorcing her. Again, the happiness of the girl was immaterial. The pain of having been raped would be compounded by having to spend the rest of her life with the assailant, subject to his will as his wife.

The laws of the Bible are less violent than those of Assyria—for example, there is no recourse to raping another man’s wife as retribution—but biblical mythology is just as savage. The book of Genesis tells the story of Dinah, daughter of the patriarch Jacob, who “went out” from her house and then was “taken” by a neighboring prince named Shechem. The text is not clear as to whether the “taking” was the result of rape, persuasion, or something in between, but there is no doubt that Shechem fell in love with Dinah and, after installing her in his house, decided to marry her. Yet he had made a terrible mistake by not going to Dinah’s family for permission before bedding her. The disgrace he brought to Jacob’s house would need to be wiped away before anything else could take place.

Shechem and his father Hamor tried to make amends by offering Jacob any bride-price he demanded, no matter how much. This offer of money would normally have been enough to assuage a family’s hurt pride and lost investment in the girl’s virginity. It seemed to have been acceptable to Jacob, but not to Dinah’s brothers, whose rage could only be assuaged with violence. They told Shechem and Hamor they would accept the offer of money, and then, after their enemies were lulled into a state of vulnerability, they made their attack:

Simeon and Levi, Dinah’s brothers, took their swords and attacked the unsuspecting city, killing every male. They put Hamor and his son Shechem to the sword and took Dinah from Shechem’s house and left. The sons of Jacob came upon the dead bodies and looted the city where their sister had been defiled. They seized their flocks and herds and donkeys and everything else of theirs in the city and out in the fields. They carried off all their wealth and all their women and children, taking as plunder everything in the houses. Jacob was angry when he heard what his sons had done, and also scared of reprisals, but Simon and Levi had one concern on their minds: “Should he [Shechem] have treated our sister like a prostitute?”

To Dinah’s brothers, the destruction of Shechem’s city and the murder and enslavement of its inhabitants constituted appropriate payback for their sister’s lost virginity. Dinah’s fate was not spelled out because it did not matter. She was merely a prop in the story. The main issue at stake was the lost honor of her male family members, and what they did to regain it. Dinah’s intentions would only have entered the picture had she sneaked off with Shechem and willingly had sex with him. Luckily for her, that did not happen.

Any Hebrew man who formally accused his bride of being impure at the time of the wedding set off a high-stakes legal process. The bride’s father would have been required to prove his daughter’s virtue, which he normally did by giving the soiled wedding bedclothes to the town elders to inspect. If the bloodstains on the fabric were deemed insufficient, the bride was stoned to death in front of her father’s house. Just as Shechem did wrong by taking what was not his, so did the sexually experienced bride commit a grave crime by deciding when, and with whom, she would have sex. (It is easy to imagine savvy fathers splattering animal blood on the bedclothes to make sure their daughters were exonerated.) If, on the other hand, the bedclothes passed inspection, then the accusing groom would be beaten by the elders, forced to pay the bride’s father one hundred silver shekels, and barred from ever seeking a divorce. Again, the bride’s well-being was of least concern. She would be condemned to living out her days with a husband who most likely hated her—a small price to pay for her family’s honor.

Given the differences in marriage value between virgins and non-virgins, it was illegal everywhere even to spread rumors that a bride was something less than intact on her wedding day. The laws of Lipit-Ishtar, another Sumerian ruler (circa 1900 BC) who predated Hammurabi, required a man making such an accusation to pay a fine if proven wrong. The question is how such proof was made. The Hebrews and others used bloody bedclothes, but that was not a universal test. Neighboring cultures were not nearly as convinced that blood always resulted from a female’s first intercourse. The only way to prove conclusively that a girl had had sex was either to catch her in the act or to observe her belly swollen with child.

Why was it so critical for men to marry untouched women? It makes sense that adultery should have been forbidden, as husbands wanted to be assured that their children were actually their own, but there is no corresponding concern with marrying sexually experienced brides. If a wife gave birth less than eight or nine months after the wedding, it would have been simple enough to allow the husband to disown the child. But ancient law did not go in that direction; rather, it barricaded women and girls from sexual opportunities and punished them if they transgressed. Explanations for the virginity obsession seem to be limited to men’s desire for a “tight fit,” as well as the assurance that the human property they purchased was truly brand new. Most likely, though, the fixation on virginity—which never existed where men were concerned and has persisted to this day in many cultures—was simply one more avenue for men to control and dominate females. Having a virgin for a bride was power incarnate for a husband, and keeping her untouched before marriage was a test of control for her fathers and brothers.

6

THE JOYS OF MARRIAGE

The sexual restrictions ancient societies placed on girls and women did not loosen with their marriages. The restraint fathers expected of their daughters was merely training for their duty of fidelity as wives. Everywhere, married women were kept on short leashes and disciplined. The Assyrian law mentioned above that allowed husbands to beat, whip, and mutilate their wives for misbehaving extended to anything short of killing them. Presumably, qualifying offenses included going about town unveiled. If only sexually available women, such as prostitutes and slaves, uncovered their heads in public, a respectable wife who did so would therefore be signaling her availability and, even worse, that her husband had lost control over her. For that, wives would suffer violence.

Married Assyrian women who kept their veils on but associated with other men were also running big risks, as were the men. Any man who “traveled” with an unrelated woman had to pay money to her husband and prove—sometimes by jumping into a swiftly flowing river and surviving—that he had not taken the woman as a sexual partner. Palace females were completely off-limits. It was a capital offense for a woman of the royal court and a man to stand together with no one else present. If another palace woman were to witness such an encounter without reporting it at once, she would be thrown into an oven.

The Code of Hammurabi made wives’ lives no less hazardous. Married women who were “not circumspect” or who shamed their husbands by disparaging them or leaving their houses without permission risked death by drowning. This penalty accomplished two purposes: It got rid of a troublesome wife and it washed away the husband’s dishonor. If a wife was so impudent as to steal her husband’s property or denigrate him in public, then he had the choice of either casting her out of his house or—in a delicious gesture of revenge—keeping her around as a slave while he remarried.

The overriding goal of these laws was to prevent even the appearance that a wife was committing adultery. Virtually nothing consumed ancient lawmakers more than female infidelity, and few crimes were so severely punished. With the exception of the Hebrews, men who had sex outside of marriage were never at risk of punishment, but even Jewish law skewed hard against women. Married Jewish men were technically discouraged from having sex with other women, but were never punished to the same degree as their wives, and prostitution flourished in ancient Hebrew society. The men were also permitted to take multiple wives and concubines.

As a rule, women in the ancient Near East who had extramarital affairs and were caught suffered, died, or suffered and then died. That this should be the case was never questioned. The main legal issues concerned just when the punishments would be inflicted, and by whom. Could a husband go on a killing spree when he learned his wife had been unfaithful, or was the state to perform the executions? Was he allowed to forgive his wife or (less likely) her paramour? Was his decision final? As far back as the Sumerian kingdom of Eshnunna, in about 1770 BC, no forgiveness was permitted. “The day [a wife] is seized in the lap of another man, she shall die, she will not live.” Later Mesopotamian cultures allowed husbands to pardon their wayward wives and not kill them, so long as they also gave a pass to the wives’ lovers. In other cases, kings had the power to trump the husband’s decision, either by pardoning the sinning couple despite the husband’s desire to kill them or vice versa.

Assuming that punishments for adultery went forward, as they must have in most cases, they were nasty indeed—at least for the women. We have already seen how the unfortunate Nin-Dada was condemned and most likely impaled on the mere suspicion that she had committed adultery with her husband’s killers. In another case from the same period, a man named Irra-malik came home to find his wife, Ishtar-ummi, making love with another man. Rather than commit violence on the spot, Irra-malik kept his head: He tied Ishtar-ummi and her lover to the bed with rope and dragged them to the assembly for trial.

Although the case record is short on detail, it appears that the assembly took the evidence in front of them—the two lovers tied and wriggling on the bed—as proof that adultery had taken place. This would have been sufficient to seal Ishtar-ummi’s fate. Irra-malik, however, decided to pile more charges upon her. He accused her of stealing from his grain storehouse (perhaps to give a gift to her lover) and opening his jar of sesame seed oil, covering it again with a cloth to hide her theft. While these additional charges seem piddling next to adultery, they were framed as part and parcel of female wrongdoing: Bad wives not only took lovers, they also wasted their husbands’ resources.

Ishtar-ummi’s life was headed for a cruel end, but death appeared to be too much for her to hope for. The assembly first ruled that her pubic hair be shaven—whether this was merely to humiliate her or to prepare her for a lifetime of slavery, we do not know. It is probable that she was to be downgraded from wife to slave in Irra-malik’s house, to be abused daily by him and his new wives. Before that happened, however, the assembly also ruled that she was to have her nose bored through with an arrow before being led around the city in disgrace, like a mule. The fate of her lover is not recorded, although it is likely that if she was not killed, neither was he.

7Wives never had any right to complain when their husbands took lovers, except when they were refused sex altogether or belittled in public. In that case, at least in Babylon, they could attempt to divorce their husbands—but that was a risky step, for the trials inevitably covered the wives’ sexual behavior as well, and if they were found to have been promiscuous themselves they were thrown into a river to die. Given the risks involved, it was a far safer, if more bitter, decision for wives simply to put up with their husband’s misbehavior.

Rivers were also involved when wives were accused of adultery without solid proof. Under what has become known as the “river ordeal,” a woman could clear herself of suspicion by having herself thrown into the water. If she survived, she was declared innocent; if she sank, she was guilty. In either instance, the matter was decided. In one case that unfolded in the Sumerian kingdom of Mari, an unnamed woman made a detailed public statement just before the start of her river ordeal. She declared that she had indeed had sex with a father and his son before marrying the father. After her wedding, while her husband was away, the son came back to her to demand sex once again. “He kissed me on my lips,” she reported. “He touched my vagina.” She insisted, however, that they never went past the heavy petting stage: “His penis did not enter my vagina.” Moreover, she scolded her aggressive stepson for coming after her, telling him that she would never do her husband “unforgivable harm” by letting him possess her again. Her declaration reads as if she doubted that she would survive the river, but the gods apparently believed her story. She floated.

A married Assyrian woman who invited a man to have sex with her could be punished by her husband in any way he chose. The lover usually walked away, but not always: If a man knew the woman in his bed was married, both were put to death. The problem for the courts was figuring out who knew what and when they knew it, especially when everyone’s stories were plausible. To decide the undecidable, the Assyrians also used the river ordeal. A man who insisted he did not know his companion was married, or who claimed that there had been no sex, could prove his case by being thrown into a river. If he lived, he was exonerated, though he still had to pay the husband for the trouble. If the accused man sank, then the matter was over for him anyway. The errant wife’s fate at that point was her husband’s decision.

One knotty Assyrian sex case began when a wife left her husband and went to another man’s house, where she stayed in the company of the host’s wife for a few nights. The runaway wife’s husband tracked her down, at which point he had the right to take her home and mutilate her to his heart’s content. The woman who had taken care of her was presumed to know she’d harbored a disloyal woman, and was subject to having her ears cut off. The male host was at risk of paying a big fine if it could be shown that he’d known his guest was married. If no one believed him, he would have to undergo a river ordeal.

Thousands of years later, the spicy details of this dispute are left to the imagination. Why did the woman leave her husband? What brought her to the new home? Was she seeking sex with the host or refuge with the host’s wife? As critical as each of these questions might seem to us, they were irrelevant to Assyrian justice. By law, husbands owned their wives, and were free to treat them as they wished. The sole issue was whether or not there was any way to assuage the fragile pride of the runaway’s husband.

THE FREEDOM OF husbands to do violence to their adulterous wives seems to have diminished slightly by the Neo- and Late Babylonian periods (roughly the seventh to sixth centuries BC). By then, punishments against wives for taking lovers were often spelled out in advance, in marriage contracts. Several of the contracts that have survived contain an interesting clause, loosely translated as “Should [the wife] be discovered with another man, she will die by the iron dagger.” Why this kind of language was put into marriage contracts at all, when the law had long allowed husbands to kill their adulterous wives, is the main question here. Were the contracts simply reminding young brides what awaited them should they stray? Perhaps, but a better interpretation is that the expression “she will die by the iron dagger” meant that the unfaithful wife would no longer be punished by the angry husband, but by state authorities, and in a public, example-setting way. As awful as dying “by the iron dagger” was, the clause was probably inserted into these contracts at the insistence of the brides’ families to limit the husbands’ options if their women were caught with other men. Rather than grant license to kill the lovers on the spot, the contracts most likely forced the husbands to bring them before the authorities. There was nothing a father could do to save his daughter’s life once she had been unfaithful, but at least he could negotiate a fair shot at justice for her.

According to the Greek historian Herodotus, it was not easy to find a faithful wife in Egypt. He told of a king named Pheros, who had gone blind after showing disrespect to the Nile. Pheros’s journey into darkness lasted for ten years, after which an oracle told him he would recover his sight when he washed his eyes with the urine of a faithful wife. Pheros went first to his own spouse, but her urine was tainted with adultery and could not heal him. He then tried the urine of “a great many” married women, one after another, until at last he found one who had been faithful—and his sight was restored. He gathered all the adulteresses he had tested (including, presumably, his own wife), sequestered them in a town known as Red Clod, and burned them to death. For good measure, he burned down the town, too. Afterward, he married the woman whose urine had retained the healing powers of fidelity.

Herodotus, of course, was all too often ready to sacrifice accuracy for a good tale, but he makes a fair point: Ancient Egyptian culture was deeply intolerant of women having extramarital sexual relations, and Egyptian law was ready to punish adulterous wives. The punishments were usually carried out by the husbands. In one account, dating to the New Kingdom (sixteenth–eleventh centuries BC), a man who had learned of his wife’s attempted seduction of his younger brother chopped her to bits and fed her to the dogs. Other records tell of a man named Webaoner, whose wife regularly met with a townsman for adulterous trysts. Webaoner hired a magic crocodile to snatch the townsman and drag him to the bottom of the river. On orders from the king, the adulterous wife was then burned alive. (Burning and dismemberment were punishments calculated not only to cause pain but also to do eternal damage, as failure to preserve the intact body of a corpse was believed to ruin a spirit’s chances to pass peacefully from this world into the afterlife.)

Not every adulterous woman in Egypt was treated with such savagery. The hocus-pocus in the stories of Pheros and Webaoner only illustrates the most extreme cases. Unless an Egyptian wife was caught in the act—in which case her husband would be forgiven for killing her in a fit of rage—she was most likely punished by having her nose slit or cut off; her lover could be given a thousand lashes. Not pleasant, to be sure—but hardly as bad as being dragged to the deep by a magic crocodile.

8

GOOD GOATS, BAD SHEEP, AND LONG-SUFFERING SLAVES

Female adultery was one of the worst sex crimes in the ancient world, but there were many others. The first written laws covered the full gamut of sexual behavior from intercourse with cows and horses to affairs with another’s slave. Sex itself was also used as a form of punishment. In Assyria, a married man who raped a virgin was considered a criminal, but it was his wife who paid the worse penalty: The law required that she be given up to be raped by the victim’s father. In Egypt around 1000 BC, bestiality was both punishment and blessing, depending on the animal and the circumstances. Men who damaged stone property markers were forced to give up their wives and children to be raped by donkeys, but sex with goats was regarded as a form of divine devotion. Herodotus later tells us that goats were often seen as incarnations of the procreative god Pan. In countless instances, woman worshipped the goat god by copulating with specially trained bucks in temples.

Hittite punishments for sex with animals also depended on the particular beast involved. Cows, dogs, and sheep were strictly off-limits. Any man taking one of them for his pleasure was subject to the death penalty. The king was permitted to spare the animal lover’s life, but the man would be treated as unclean and would never be allowed in the king’s company “lest he defile the royal person.” Sexual relations with horses and mules were permitted, but reluctantly. Men who enjoyed the intimate company of these animals would not risk execution, but they were barred from approaching the king and from becoming priests. Oxen and pigs were treated as potential sexual predators: Any ox that turned from its labor and “leaped” on a man “in sexual excitement” was to be killed. The man would escape execution, but a sheep was killed in his place. As for pigs, the law was clear that it was “not an offense” when a pig raped a man—but if the man was the sexual initiator, he was put to death.

Rape between human beings was also dealt with according to who was doing the raping and who was suffering it. We have already considered the penalties for raping betrothed virgins. Husbands, of course, could never be charged with raping their own wives; the idea would have been regarded as incomprehensible, if not insane. Men owned their wives, and were at liberty to use them at their pleasure. Men also owned their slaves, though slaves were not technically people and thus had far fewer rights. Giving oneself to one’s master sexually was part of the job description. The question in terms of the law was what to do when a freeman had sex with another freeman’s slave without first obtaining permission. On that subject, ancient lawmakers had much to say.

As far back as the days of Ur-Nammu, in the third millennium BC, the penalty for raping a slave girl was as trivial as a speeding ticket is today. A fine of five silver shekels was levied, but that was it. It was not much different in Babylon, where the fine for taking another man’s virgin slave girl rose to twenty silver shekels, and so on into the era of Hammurabi. In one famous Babylonian case, again before the Assembly of Nippur, a man named Lugalmelam was accused by the slave owner Kuguzana of “seizing” his slave girl, dragging her into a building, and then “deflowering” her. Lugalmelam denied everything, but Kuguzana found witnesses to back up his charges. The assembly decided that Lugalmelam had indeed taken the girl “without her owner’s knowledge,” and charged him a substantial fine.

It need hardly be pointed out that no one asked Kuguzana’s slave whether or not she had consented to having sex with Lugalmelam. The only consent that mattered was that of her owner. Slaves were bought and sold like animals, given as gifts, offered in payment of debts, and shipped abroad as merchandise. At any moment in their perilous lives, their owners could use them as they wished. Even the rules against sex within families were loosened when slaves were involved, as no one recognized that slaves themselves could have families as such. Under the laws of the Hittites, for example, if a freeman had sex with sisters and their mother, “it [was] an abomination,” but if he slept with slave sisters and their mother, “it [was] not an offense.”

The cruelty of slavery was nevertheless sometimes softened, especially when slaves produced children for their masters. Under the Code of Hammurabi, a slave concubine who bore her master’s children was automatically freed after he died. If a slave owner was forced to hand over a female slave to pay a debt, moreover, he was allowed to buy her back later if she had already given him children. This situation must have come up with some regularity, as female slaves were often used as surrogate mothers. When a freeman’s wife was unable to have children, she was permitted to find a slave woman to do the job. The slave was then given certain additional rights, though not enough to challenge the wife’s position in the household. The laws of Lipit-Ishtar required that the slave mother not live in the house of her masters. The Babylonians went one step further, explicitly allowing the wife to continue treating the slave-mother as a piece of property.

The rape of a married woman incurred the death penalty only when it took place on the open road, and only if the woman had vigorously fought back. The fact that the sex occurred outdoors, and that she did her best to stop it, helped show that she was taken by surprise and was not looking to have an affair. If she was at home when the sex occurred, the suspicion of bad intentions on her part was almost impossible to shake. The Hittites, in fact, resolved cases of home rape against the wife even before it occurred:

If a man seizes a woman in the mountains (and rapes her), it is the man’s offense, but if he seizes her in her house, it is the woman’s offense: the woman shall die. If the woman’s husband discovers them in the act, he may kill them without committing a crime.9

PROSTITUTION, SACRED AND PROFANE

The rules changed when sex was for sale. Prostitution was a legal transaction like any other, so long as it was carried out according to custom and respectable women were not involved. An Assyrian man who had sex with a married woman in a tavern or brothel (which were often one and the same) could be put to death for taking another man’s wife, but his knowledge of the fact that she was married would first have to be proven—which could be difficult, given the circumstances. If he could show that he had believed he was paying a single woman for her company, then no one could lay a hand on him, even if she had been married to an aristocrat.

In Egypt, religion and prostitution were closely associated. The Egyptian goddess Isis was, among her many other incarnations, a whore. At first, prostitution was barred from religious precincts. However, by the time the geographer Strabo traveled in Egypt in 25 BC, customs had changed. In the temple of Zeus, prepubescent girls were being served up for men’s pleasure:

To Zeus they consecrate one of the most beautiful girls of the most illustrious family . . . She becomes a prostitute and has intercourse with whomever she wishes, until the . . . purification of her body [by menstruation] takes place. After her purification, she is given in marriage to a man, but before the marriage and after her time as a prostitute, a . . . ceremony of mourning is celebrated in her honor.

Herodotus wrote of another girl who had got into the trade: the daughter of the pharaoh Khufu (or Cheops, 2589–2566 BC). Her life was decidedly unglamorous, however. She was put to work on her back to pay for her father’s death monument:

When [Khufu] was short of money, he sent his daughter to a bawdy house with instructions to charge a certain sum—they did not tell me how much. This she actually did, adding to it a further transaction of her own; for with the intention of leaving something to be remembered by after her death, she asked each of her customers to give her a block of stone, and of these stones (the story goes) was built the middle pyramid of the three which stand in front of the great pyramid. It is a hundred and fifty feet square.

That’s a lot of stones, and a lot of clients.

Another story from Herodotus told of the Thracian prostitute Rhodipus, a beauty whose hard work in Egypt brought her great fame and wealth, some of which she used to dedicate temples at Delphi. Rhodipus worked with the opportunities she had: Selling sex, sacred or otherwise, was one of the few ways unmarried women could get ahead. In Egypt, women were nearly equal to men under the law—but only in theory. Only money could buy true independence, and there were few ways in Egypt for women to earn their own living. Unless they were supported by men, their options were limited to prostitution, the performing arts, or, as was often the case, a little of each at the same time. The droves of prostitutes who did not reach the heights of Rhodipus trailed construction crews to building sites and followed pilgrims to religious destinations. It was tough going and made for short, bitter lives.

No Mesopotamian civilization attached any stigma or restriction to prostitution. By 1750 BC, during Hammurabi’s reign, the city of Babylon was busy with trade (both male and female) in the temples and on the streets. Temple prostitutes were the most desirable, and the most expensive. Their precise religious function is unclear, but it seems they worked both as skilled pleasure-givers and as intermediaries between customers/worshippers and temple deities. Whether the path to godliness truly ran through the body of a woman selling sex is anyone’s guess, but this was doubtless a profitable form of worship. The earnings of sacred prostitutes comprised a substantial part of the temples’ revenues.

The Babylonians forced all women to put in time as temple prostitutes. According to Herodotus: “[E]very woman who is a native of the country must once in her life go to the temple of Aphrodite and there give herself to a strange man.” Only after they had performed this duty were they permitted to leave. The scene at the temple was chaotic, with women and customers constantly coming and going. Women from the wealthy classes arrived to do their service in covered carriages with dozens of servants milling about, while others showed up on foot. Special gangways were installed to permit the men to stroll through the assembled females and make their selections. “Once a woman has taken her seat she is not allowed to go home until a man has thrown a silver coin in her lap and taken her outside to lie with her,” Herodotus continues. The attractive ones were plucked up right away, while the homely ones were sometimes forced to remain on display at the temple for years. Once their service was done, the women were off-limits once again.

Attractive Babylonian women also assisted their less beguiling neighbors in finding a mate. Once a year, all girls of marriageable age were collected from their villages to be auctioned off to prospective husbands. The pretty ones from good families were taken first, often after furious bidding, while “the humbler [men], who had no use for good looks in a wife, were actually paid to take the ugly ones.” When all the attractive women had been sold, the auctioneer “would call upon the plainest one to stand up, and then ask who was willing to take the least money to marry her—and she was knocked down to whoever accepted the smallest sum.” The money came from the sales of the beauties, “who in this way provided dowries for their ugly or misshapen sisters.”

Men lacking the means to purchase temple whores could frequent downscale taverns and wine shops. Both the prostitutes and the (mostly) female proprietors of these dives were seen as a sluttish, thieving lot. Drinking houses were often hideouts for fugitive bandits, which is why Hammurabi took pains to control them, while imposing no restrictions on the tavern-based prostitution within. A barkeep marketing prostitutes in her back room was liable for nothing more than taxes, but faced capital punishment if she overheard customers talking about a crime and failed to turn them in.

Strict dress codes had the dual effect of putting prostitutes on perpetual display as well as making clear which women were unavailable for rent. From the earliest Sumerian times, married women went veiled. By the Middle Assyrian period, this tradition had evolved into a harsh law that made veiling a privilege of the better classes. Prostitutes and slaves were not permitted to go about veiled. Conversely, all daughters, wives, widows, and other women of status were to be covered in public. Prostitutes caught wearing veils had hot pitch poured on their heads and were beaten with fifty blows. Such punishment left them disfigured and, undoubtedly, less salable. Slaves who hid their faces in public, meanwhile, stood to lose their ears and their clothes.

10

HOMOSEXUALITY BEFORE MORALITY

Before the biblical period, sex law had nothing to do with morality as we know it, nor was forbidden sex laden with the psychology of guilt. The main question concerned the protection of property. The founding principle of sex regulation was that women were possessions to be cultivated for marriage and childbirth, or used for sex and then discarded. A husband was free to fornicate to his heart’s content, because it had no effect on his property. His wife, of course, could be put to death for doing the same thing.

The question then turns to whether or not men had the option of fornicating with other men, and the short answer is that they usually did. Before the Hebrews labeled male-male sex an abomination of the worst kind, there were almost no restrictions against it. As detailed as the early legal codes were on the subject of sex, same-gender relations were mostly ignored—not because homosexual sex did not take place (it certainly did), but because there was no reason to actively restrict it: Anal sex generally was subject to no taboos, and sexual escapades among men constituted no more of an interruption to their marriages than their dalliances with female prostitutes or slaves. Male prostitutes even worked in the Babylonian temple of the mother-goddess Ishtar at Erach, where they were known as men “whose manhood Ishtar has changed into womanhood.”

The Assyrians shared the Babylonians’ indulgent attitudes, but only up to a point. A man who spread false rumors that another man allowed himself to be regularly penetrated was subject to being whipped, fined, and having his hair cut off. Such punishments were mild by Assyrian standards, and they did not mean gay sex was illegal; but they do indicate that being considered as available for the pleasure of other men was bad for a man’s reputation. Far worse was the rape of a man by another of his own class. For that, the aggressor was punished by rape, followed by castration. Yet we still cannot say with certainty that these laws signaled a general retreat from thousands of years of legal indifference to homosexual relations. The law, after all, only prohibited rape between men of the same class. A master’s forced penetration of his male slave was perfectly legal, as were relations with male prostitutes and consenting male acquaintances. Taken together, however, they probably contributed to a mind-set that viewed same-gender sex as being somewhat inferior to heterosexual relations. The Hebrews would carry this idea to extreme lengths, as they did with their rules forbidding every form of sex that wasn’t intended to produce legitimate children.

11

SIN: THE GIFT OF THE HEBREWS

From about 1047 to 597 BC, a collection of contentious Hebrew tribes had held unsteady control over coastal land in Palestine, where they lived by their own religious law. The early Jews developed their legal system with a view to surviving in a region filled with other ethnic tribes, with whom they were at war; but the true accomplishment of their laws was to differentiate the Hebrews by imposing the stamp of “Jewishness” on just about everything they did. Integral to that sensibility was an intense preoccupation with restricting sexual activity. The Jews meant to make their entire lives holy, whether in their business dealings, their food customs, or their methods for having sex. To achieve this, they developed a sprawling range of rules and regulations. The Hebrew kingdoms were short-lived, and, compared to the colossal ancient empires of Persia and the Mediterranean, insignificant. Had Judaism not spawned Christianity and then Islam, Hebrew law would have remained a marginal development in Western history. Like the laws of the Babylonians and the ancient Egyptians, the Hebrew Bible would have been chiefly of interest to later academics. Instead, the moral strictures of the ancient Jews, held together with the molasses of shame and the terror of God’s punishment, have been more influential on Western sexual attitudes than any other collection of ideas.

The body of Jewish law is immense, so broad that it is virtually unknowable to any individual. I shall concentrate here mostly on the rules that were supposedly dictated, word for word, to Moses by God—in particular the book of Leviticus, where most of Judaism’s most significant rules concerning sex are to be found. Maddening in its repetitious hodgepodge of demands, threats, and curses, Leviticus is one of the foundations of Hebrew life, and, along with the rest of the Torah, is meant to be an indispensable guidebook to a godly existence. Nothing before or since has so effectively equated the body, the state, and the collective moral soul.

Jewish law places no distance between flesh and spirit. The body, considered an extension of God, was to be harnessed in building a holy nation. “You shall sanctify yourself and be holy, for I am holy,” commands God, and in Leviticus he instructs the children of Israel how to do this. To follow God’s commandments was to live, to “be fruitful and multiply” (Genesis 1:28); to ignore them was, in extreme cases, to anger God to the point where he would “vomit out” the Jews from the land they held so tenuously. Every passing thought had powerful social and religious significance, and everything a Hebrew did with his or her body, more so. Sex and reproduction were thus at the core of Hebrew lives and law.

The scriptures spell out in detail what may go in and out of the body, particularly via the mouth and genitals. Many foods are forbidden, as God’s decree holds that they cause contamination. A multitude of bodily fluids such as menstrual blood and semen are also regarded as polluting, and must be carefully channeled lest they infect the community. Sexual intercourse was necessary to fulfill the commandment to multiply, but it took very little to transform the sex act from one of blessed procreation into a sin that put the entire nation at risk. While sex was essential to marriage, it was also a political act: Having sex (or rejecting it) according to Mosaic law was both a declaration of faith and a repudiation of the Hebrews’ hostile neighbors.

Before God spelled out the multiple sexual prohibitions in Leviticus, he issued a commandment

not to “do [have sex] as they do in Egypt, where you used to live,” and also “not [to] do as they do in the land of Canaan, where I am bringing you. Do not follow their practices.” There were many such “practices” to reject, including incest and bestiality (both were prevalent in Egypt), which became death-penalty crimes, and the temple prostitution common in Canaan and Babylon. To further distinguish the Hebrews from the cultures around them, Leviticus also forbade adultery by men as well as women. Violating any of these prohibitions thus not only made one immoral in the eyes of God, but also subverted everyone else’s safety.

12

CIRCUMCISION AND FLUID CONTROL

One practice the Jews did adopt from their neighbors was male circumcision; the Egyptians had already been snipping off the foreskins of their boys and male adolescents since the third millennium BC, long before the Hebrews began to do so. The ritual, performed by Egyptian “circumcision priests,” was done on as many as 120 males at a time. Although, in Genesis 17:9–11, Abraham receives a divine revelation that male circumcision is to mark a “covenant” between God and his followers, the practice is said to have become institutionalized only when the Hebrews fled Egypt—presumably reinforced by the Egyptian convention. For good measure, the Hebrews also circumcised their slaves, as well as all slaves bought with their money. To be uncircumcised was to be unclean. The practice of circumcision later spread throughout the Near East and became common among Muslims (although it is not required by Islamic law).

The surgical modification of a boy’s reproductive equipment is a strong statement of faith, but there remains the question of whether or not it was also meant to affect his later erotic experiences. The medieval Jewish scholar Moses Maimonides argued that circumcision decreases sexual desire, which he thought was a good thing. He was not alone: In the nineteenth century, circumcision was one of the “cures” used to reduce the urge to masturbate. Some modern researchers agree that the procedure diminishes sensation, which they refer to as “erotic harm.” In many countries where circumcision is common, notes one authority, “women must often become accustomed to performing fellatio (the so-called ‘Berber wake-up call’) on men to spur their sexual response.”

The thirteenth-century Jewish sage Isaac Ben Yedaya argued, by contrast, that circumcision

increases male erotic sensation to the point of sparking premature ejaculation:

He will find himself performing his task quickly, emitting his seed as soon as he inserts the crown. If he lies with her once, he sleeps satisfied, and will not know her again for another seven days . . . As soon as he begins intercourse with her, he immediately comes to a climax. She has no pleasure from him when she lies down or when she arises . . . [S]he remains in a state of desire for her husband, ashamed and confounded.

To Ben Yedaya, this was preferable, as uncircumcised men give women too much pleasure, which in turn invites a host of different problems:

She too will court the man who is uncircumcised in the flesh and lie against his breast with great passion, for he thrusts inside her a long time because of his foreskin, which is a barrier against ejaculation in intercourse. Thus she feels pleasure and reaches an orgasm first. When an uncircumcised man sleeps with her and then resolves to return to his home, she brazenly grasps him, holding on to his genitals, and says, “Come back, make love to me.” This is because of the pleasure that she finds in intercourse with him, from the sinews of his testicles—sinews of iron—and from his ejaculation—that of a horse—which he shoots like an arrow into her womb.

Whatever its long-term erotic effects, circumcision was rejected by the Greeks and Romans, who found the practice repulsive and barbaric. The Greeks viewed penile foreskins as emblems of virtue and strength; altering nature’s design was nothing more than the odd fetish of oddball religious cults. The Greek king Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175–164 BC) outlawed circumcision altogether, as did later Roman edicts punishing circumcision with death. Some Jews, wishing to escape punishment and integrate themselves into pagan cultures, mutilated themselves trying to restore their foreskins—but such measures are rare in the record.

13Being a Jewish male has always meant, first and foremost, being circumcised. Unless their foreskins were removed, Jewish males were considered impure. Circumcision was only the first step in a sanctified life, however; staying pure before God took constant effort, as impurity hovered around all sexual activity. When a husband and wife had sex, for example, the transmission of semen made them both unsuitable for contact with anyone else. Until they were cleansed, everything they touched was contaminated. Even an involuntary discharge of semen, such as sometimes accompanies a man’s erotic dreams, was an unhygienic catastrophe. The bed in which the dream took place was now defiled, the bedclothes unusable until scrubbed, and any clay pots touched by the man were considered so unclean they had to be smashed to bits. This process would continue for a week, after which the hapless wet dreamer was compelled to seek out a priest to help him make a sacrifice of doves or pigeons and beseech God’s forgiveness. Menstrual blood was no less radioactive: Any contact with it required intense cleansing efforts and strict separation of the offending woman from the community until the taint was washed away.

When the body’s fluids were misused through forbidden sex, the risk was multiplied drastically. An individual’s defilement, if bad enough, tempted God to destroy the Jewish nation in its entirety. God makes his position quite clear:

Do not defile yourselves [sexually], because this is how the nations that I am going to drive out before you became defiled. Even the land was defiled; so I punished it for its sin, and the land vomited out its inhabitants. But you must keep my decrees and my laws. The native-born and the aliens living among you must not do any of these detestable things, for all these things were done by the people who lived in the land before you, and the land became defiled. And if you defile the land, it will vomit you out as it vomited out the nations that were before you.

In other words, “Follow my commandments and you will live. Ignore them and I will throw you off the land and will kill all of you.”

If sex between a man and a menstruating woman polluted them both, the mixture of fluids between humans and animals was far worse: Both the human offender and the animal were to be killed.

14 Incest was no different, as it represented an intermingling among family that would then infect everyone. In its most intimate forms, such as copulation between a mother and son, the law demanded that both parties be killed.

Given the above, one Bible story is particularly ironic, telling of a man who paid a terrible price for refusing to engage in intrafamily sex. According to Genesis, following the death of a man named Er, God commanded Er’s brother Onan to impregnate the deceased’s wife. Onan obeyed to the point of going to bed with the widow several times, but each time he “spilled his semen on the ground” rather than ejaculate inside her. God was not amused, and struck Onan dead. In the context of ancient life, God’s demand was not unusual. When a husband died without issue, it was common in many societies for his brother to take the widow as a wife and try his best to give her children. Onan’s sin was rebellion against this custom (called levirate marriage) via coitus interruptus.

As the practice of levirate marriage diminished over the years, the story of Onan should have faded from interest as well. But it found new life when Christian theologians seized it to emphasize that any form of semen wastage was forbidden, whether accomplished by masturbation, unfinished copulation, or otherwise. The masturbation angle resonated more than the others, to the point where “Onanism” came to denote self-abuse. In the eighteenth century, the Swiss doctor Samuel-Auguste Tissot named his hugely popular antimasturbation diatribe L’Onanisme, after the man who refused to complete the sex act with his sister-in-law.

The Jews also tightened regional prohibitions against adultery, throwing it in the gallery of crimes so abominable they put all Hebrews at risk of destruction. Other Near Eastern laws let the cuckolded husband punish his wife and her paramour—which was logical, given that it was the husband who was “injured” by the wife’s infidelity. Jewish law saw the crime differently. A wife’s straying from her husband was condemned as treason against the entire community, which demanded public involvement and communal retribution. For everyone’s benefit,

both male and female adulterers were supposed to be publicly strangled. The law was no less strict when sex took place between a man and a girl who was engaged to be married. The pair would be stripped and placed on public ground to suffer large stones dropped on their bodies until they died.

15The Hebrews expanded the reach of adultery law, but not at the expense of their men’s sexual freedom. Married men were not allowed to have affairs as such, but they were permitted to take as many wives as they pleased—King Solomon reputedly had seven hundred official wives—and also to keep concubines and visit prostitutes. A Jewish man was forbidden from marrying a prostitute, but even on that point the law was rather weak. Unlike other ancient societies, in which a woman was marked as a whore for her entire life once she took up the trade, a prostitute in ancient Palestine could marry a Jewish man if she reformed herself for at least three months.

As for other girls who sought premarital sexual experiences, Jewish law was relatively lenient. A lost maidenhead was gone forever, to the permanent detriment of the girl’s marriage value, but the Bible dictated a simple solution: Unmarried males and females (other than prostitutes) who had sex had to get married. The boy’s family had to pay the girl’s top bride-price (as though she were still a virgin), and the girl’s father had no choice but to accept both the money and the union. The premarital sex would force the father’s hand in granting his consent, but it also required the lovers to live with their decision for the rest of their lives: Divorce between the new husband and wife was forbidden.