2

HONOR AMONG (MOSTLY) MEN: CASES FROM ANCIENT GREECE

NEITHER THE SEX slave nor the wife ever had a chance. On every Athens street corner, every statue of the god Hermes, his penis erect, pointed to female powerlessness. The slave could not hope for loyalty from her owner, Philoneos—not when he could sell or torture her on a whim. Nor did the wife of Philoneos’s friend have any right to demand fidelity from her husband. The dust of the city’s streets was stamped everywhere with the prints of prostitutes’ studded sandals, beckoning with messages like “Follow Me,” and nothing prevented men from pursuing these trails directly to the city’s houses of pleasure. So when Philoneos decided to sell his slave to a brothel, and when his friend began to lose interest in his wife, the two women were left with few options to keep their men. They were desperate.

One evening, when the two men were drinking together at the husband’s house, the wife called the slave over. In whispers, she told the girl that she had obtained a potion that would turn their men’s attention back to them. The only question was how the women would slip it to them. The men dined habitually with concubines and prostitutes, not their slave or wife. Nevertheless, the wife suggested that the slave do it, and this was agreed.

The opportunity came when Philoneos and the husband were together in Piraeus, the port of Athens. Philoneos was there to offer a sacrifice to Zeus; the husband was preparing to embark on a sea journey. The two friends set about eating a good meal and getting drunk. Afterward, they burned frankincense and poured libations “to secure the favor of heaven.” While they offered up their prayers, the slave poured the philter the wife had given her into their wine, pouring the lion’s share of the potion in her master’s cup.

The concoction was not the “happy inspiration” the women had hoped for: It killed Philoneos that night. The husband died from the poison a few weeks later.

These were some of the accusations made by the husband’s son at the murder trial of the wife, his stepmother—hence the case was referred to as Against the Stepmother. The young man had not been present during any of the critical events; his evidence came from the sex slave’s agonized confession as she was being broken on a wheel. The stepson accused his stepmother of tricking the slave into poisoning his father to death, but the slave couldn’t confirm this. Nevertheless, all trials are about stories more than realities, and the stepson’s tale was compelling. The jury, which numbered up to 2,501 men, was unlikely to give the wife a break in any event. The mere fact that she would try to mold her husband’s emotions, even with a substance she might have believed harmless, was bad enough.

A well-known orator named Lysias had been hired by the stepson to write his trial speech. Lysias well knew the whoring habits and misogyny of Athenian men. He himself was a loyal client of a well-known Corinthian brothel, and likely of others in Athens itself. He crafted the stepson’s speech to push all the right emotional buttons and bring the jury to a state of maximum anger.

The slave was killed without trial, despite everyone’s agreement that she hadn’t meant to harm anyone. “She got what she deserved,” Lysias said. The specifics of the wife’s fate are not recorded, but it is clear that the rest of her life was going to be short and unpleasant. If the jury agreed that her aim had been to kill her husband rather than merely pump him up with aphrodisiacs, she probably would have faced strangulation. Avoiding execution would have been little better for her, as she would have been returned to the control of a male family member who would be certain to mete out his own home-based punishment.

1The accusation of murder that the son leveled against his stepmother is understandable, but the question of why she would intentionally kill her husband remains: Doing away with him, after all, meant eliminating the one person able to protect her from oblivion. Her actions only make sense if she had been trying to bring her husband closer to her. She was reaching the end of her useful life, knew little of the world, and had few to zero prospects without him. Marriage in Greece was meant to generate heirs for fathers, but her husband had already had a son when she married him. Minus his desire, she was more vulnerable than ever to being replaced with a newer model.

A respectable woman in Athens was viewed as merely a sperm receptacle, what Sophocles called a “field to plow.” Semen was held to do the real work in conception; the womb merely cooked it up. Aeschylus (in his

Eumenides) put it bluntly:

She who is called the mother is not her offspring’s

Parent, but nurse to the newly

sown embryo.

The male—who mounts—begets.

The key function of women was physical in Greek culture. It was thus pointless to educate them or to allow them to participate in public life. Instead, they spent their days in the airless inner rooms of walled-in houses, interacting only with slaves and family. Wives never attended their husbands’ whore-greased dinner parties, called symposia, nor did they interact much with their husbands in daily life. The differences between husband and wife in age and cultivation, along with the availability to men of sex from other quarters, virtually guaranteed that spouses would remain strangers to each other. Recognizing this, the early Athenian lawgiver Solon required men to mount their wives three times per month: Sex between husbands and wives was thus a legal duty.

Men could divorce their wives by simply returning the dowries to their fathers-in-law. Women, on the other hand, needed first to get the approval of a male relative, then go to court—the single opportunity in their lives to do so—and take their chances. After spending so much of their existence indoors, encouraged to say little and think less, choosing such a course must have been like emerging from a dark cave into blinding sunlight.

Only three women are known to have attempted divorce, most notably Hipparete, wife of the volatile and sexually unquenchable general Alcibiades. Her disastrous experience was a cautionary tale for other wives, especially as she had a good case: She came from a wealthy family, had a clear reputation, and had been repeatedly humiliated by her husband.

The union between Hipparete and Alcibiades had gotten off to a bad start. On a humorous bet with friends, Alcibiades had punched Hipparete’s father Hipponicus III in the face. When the rest of town didn’t get the joke and Alcibiades’s reputation began to suffer, he went to Hipponicus, ripped off his own clothes, and begged the old man to flog and chastise him any way he saw fit. Hipponicus demurred, but was impressed by the young aristocrat’s bravado and offered up Hipparete for marriage. Alcibiades took her in exchange for a dowry of ten talents. (He later bullied the family into giving him ten more.)

Hipparete was a dutiful wife, but she could not suffer Alcibiades’s constant debaucheries, especially his habit of bringing home foreign prostitutes. Thinking she could influence him by making a dramatic move, she went to live with her brother. Alcibiades barely noticed. Finally, Hipparete went to court to plead for a divorce. She must have known that her chances were long, but at least this way Alcibiades risked being forced to return the twenty talents to her family. That got his attention.

The law courts were located in the agora, the city’s tumultuous nerve center, where food vendors crowded with streetwalkers and magistrates and the shouts of Phoenician merchants competed with bell-clanging fishmongers. Alcibiades was known as a powerful, brilliant, and temperamental figure, and was admired as a public speaker—which, in Athens, was saying quite a lot. This time, however, he was in no mood to talk: He had been disrespected by his wife and stood to lose control of a fortune. He marched through the agora, seized her, and carried her home.

As the unhappy couple passed the statues of Hermes that marked the agora’s boundary, the crowd must have been entertained by the unusual (but not illegal) sight of one of the most admired men in Athens dragging his wife around like a barbarian. Far from trying to stop Alcibiades, they probably nodded their approval for taking the problem in hand. Plutarch, considering the case around 450 years later in his

Life of Alcibiades, believed the Athenian was doing the right thing under the law:

I should explain that this violence of his was not regarded as being either inhuman or contrary to the law. Indeed, it would appear that the law, in laying it down that the wife who wishes to separate from her husband must attend the court in person, is actually designed to give the husband the opportunity to meet her and recover her.

So much for an Athenian woman’s right to complain of her husband’s infidelity. Hipparete died in Alcibiades’s house not long afterward. Years later, Alcibiades himself was killed in Turkey—by some accounts at the hands of the family of a wellborn girl he had seduced.

2

WHERE THE WIFE in Against the Stepmother had probably tried to save her marriage by having her husband’s slave spike his wine, the slave herself was attempting to preserve an intimacy she had no right to expect. By law, slaves weren’t sentient beings worthy of protection; they were thus prey to all who owned or rented them. Not all slaves were prostitutes, and not all prostitutes slaves—but the two roles overlapped often enough. The slave in Stepmother was likely a hetaera, an upper-end courtesan of the type hired to spice up symposia with conversation, music, and dance. Their performance and sex fees were regulated and taxed, though price limits were ignored in bidding wars for the most desirable ones.

Despite the mercantile basis of their affections, many hetaerae grew close to their clients, and sometimes had children by them. But slave prostitutes were still slaves, and therefore vulnerable. Their owners had every right to sell them, syndicate their sexual services to multiple investors, or, as the slave in Against the Stepmother feared, consign them to brothels and forget about them.

A special legal council resolved investor disputes over prostitutes, which sometimes became complicated. One knotty court case, referred to as On a Wound by Premeditation, involved two men who had come to blows over an unnamed slave concubine. The problem arose following an agreement to settle a business dispute by exchanging property. The slave was transferred along with oxen and other goods, but the two men disagreed as to whether she would be available to both of them on a shared basis—as the defendant argued—or whether she would become the plaintiff’s sole sexual property.

Fortified by an evening of drinking with “boys and flute-girls,” the defendant broke into the plaintiff’s house with some friends, grabbed a shard of broken pottery, and hit the plaintiff with it, blackening his eye. The plaintiff sued, claiming the defendant had tried to kill him. The latter testified that he had been too drunk to intend much of anything and was, in any event, justified in his attack, as the girl was his to share. He also argued that the slave was the one best equipped to resolve the issue, as she was a witness to nearly everything that had transpired. As the law held that a slave’s testimony was only allowable if obtained by torture, the best thing to do, he added, was to inflict pain upon her and hear what she had to say. (The defendant may have cared for her, but not enough to think twice before putting her through agony.)

As with many Athenian court cases, the record is not complete. The defendant was facing exile, and the plaintiff risked losing control over the woman. If the case looked as though it was going to favor the defendant, the plaintiff probably would have agreed to serve up the slave for torture. However, unlike the slave in

Stepmother, her life was probably safe—at least two men still desired her.

3

THE THRUST OF ATHENIAN SEX LAW

In both Stepmother and Wound, sex was the cause of the offense, not the crime itself. There was little direct regulation of sexual behavior in Athens, or anywhere in ancient Greece for that matter. What laws there were advanced two main goals: safeguarding the honorable participation of male citizens in public life, and ensuring that fathers could leave property to their legitimate sons without complications. Unless one of these concerns was affected by sexual behavior, it is likely that a given carnal conduct was permitted.

A man’s honor was a fragile bloom to be pampered and kept on display. Courts in the contemporary United States and United Kingdom often reject what is called “character evidence” on the grounds that a person’s reputation does not indicate how he or she will act. The opposite was true in small, gossipy Athens, where a man’s reputation was always up for review. In many cases, verdicts were based on a jury’s opinion of a man’s whole life, not just on the facts of the case at hand. Given that juries could number in the thousands, a good slice of the citizenry made these calls.

Athens was not a place for rugged individualists. A man of standing lived his life in public, away from his wife. “This is a peculiarity of ours,” said Pericles. “[W]e do not say that a man who takes no interest in politics minds his private business. We say that he has no business at all.”

Women could be sued and put to death, but were not allowed to testify in court. Instead, they testified out of court or their men testified for them. Moreover, too much female company was potentially toxic to a man’s reputation. A man “under the influence of a woman” was classified along with the old, insane, and sick as incompetent to testify in court.

Though men married unschooled ciphers and kept them in seclusion, they could never be too sure about their wives’ loyalty. Women were thought to possess a molten sexuality that required constant vigilance. Rakes and roués lurked everywhere, ready to jump between the legs of hungry wives and wreck a good man’s reputation. Moreover, female fidelity ensured that a man’s children were indeed his own. His honor, in turn, depended on his ability to enforce that purity.

In early Greece, the head of an

oikos, or extended household, guarded his family’s reputation with his fists. But as the

oikos became absorbed into larger communities, it was no longer practical for angry patriarchs and their clans to be storming around the countryside attacking every man they suspected of dishonoring them. The rules of urban society prevented blood feuds, but also raised the stakes of some sexual transgressions. No longer was sexual infidelity a private matter of concern; it became everyone’s problem.

4

CAUGHT IN THE ACT

Adultery was never far from the minds of Athenian husbands. By the time the city’s earliest legislator, Draco, laid down its first written constitution, in about 620 BC, efforts were being made to reconcile honorable revenge with the prevention of inter-oikos warfare. Men could cheat on their wives, but could not take another man’s woman. Doing so brought penalties, depending on where the taking took place. If the sex happened in the street, whether by force or not, the ravisher only paid a fine. If he crossed into the husband’s house, and if the couple was caught in flagrante, he could be killed immediately. Sounds simple enough, but—as shown in the trial of one Euphiletus for the killing of his wife’s lover, Eratosthenes—application of the rule could prove a challenge.

Eratosthenes was a practiced seducer of women. Rather than pluck his quarries from the safe ranks of foreigners, slaves, and prostitutes, he liked risk. That meant hanging around the few places where married women appeared, such as funerals and religious festivals. Indeed, Eratosthenes spotted Euphiletus’s wife at a funeral, and later sent her messages via her maid, expressing his desire for her. She was interested, and the affair began.

Liaisons were made easier by the layout of the married couple’s house. Men and women in Athens typically occupied different floors, which were connected only by a ladder. Euphiletus slept upstairs to allow his wife to care for their baby below. He later told the jury that he had slept peacefully, confident that his wife was “the chastest woman in all the city” and ignorant of the fact that she and Eratosthenes were going at it downstairs. “This went on for a long time,” he said, “and I had not the slightest suspicion.”

The lovers had one close call when Euphiletus returned early from a trip out of town. Eratosthenes hid while the wife gave Euphiletus a warm welcome, a good meal, and a taste of her love. All was peaceful until the baby started to cry downstairs; Euphiletus told his wife to go calm the child. She resisted, saying she was worried he would take the opportunity to violate the upstairs maid. “Once before, too, when you were drunk, you pulled her about,” the wife joked. Euphiletus laughed too, nevertheless insisting that she go downstairs. She followed his instructions, but first “playfully” locked his bedroom door and put away the ladder. The following morning, she returned to him, wearing makeup. He asked what all the nighttime creaking had been about, and was told that she had had to go to a neighbor’s house to rekindle the lamp in the child’s room.

With Euphiletus missing such obvious signs of his wife’s infidelity, the affair could have gone on indefinitely had not one of Eratosthenes’s rejected lovers decided to retaliate against him. She sent her “old hag” of a maid to tell Euphiletus the truth: “[Eratosthenes] has debauched not only your wife,” the maid said, “but many others besides; he makes an art of it.” Euphiletus went to his own maid and told her to tell him the truth or “be whipped and thrown into a mill.” She took the first option.

To the jury, Euphiletus described the ambush he staged a few evenings later:

Eratosthenes made his entry; and the maid wakened me and told me that he was in the house.

I told her to watch the door; and going downstairs, I slipped out noiselessly.

I went to the houses of one man after another. Some I found at home; others, I was told, were out of town. So collecting as many as I could of those who were there, I went back. We procured torches from the shop near by, and entered my house. The door had been left open by arrangement with the maid.

We forced the bedroom door. The first of us to enter saw him still lying beside my wife. Those who followed saw him standing naked on the bed. I knocked him down, members of the jury, with one blow. I then twisted his hands behind his back and tied them. And then I asked him why he was committing this crime against me, of breaking into my house.

He answered that he admitted his guilt; but he begged and besought me not to kill him, to accept a money payment instead. But I replied: “It is not I who shall be killing you, but the law of the state, which you, in transgressing, have valued less highly than your own pleasure. You have preferred to commit this great crime against my wife and my children, rather than to obey the law and be of decent behaviour.”

Thus, members of the jury, this man met the fate which the laws prescribe to wrongdoers of his kind.

Eratosthenes’s fate was death on the spot at the hands of Euphiletus. A murder prosecution by the dead man’s family followed.

At trial, the jury would judge Eratosthenes as either a guilty murderer or an innocent wronged husband, nothing in between. Draco’s laws could allow Euphiletus to beat a murder rap if he could prove he caught his rival while having sex with his wife. If Euphiletus had only found them lying in bed relaxing after making love, it would have been too late. Euphiletus’s recruitment of his neighbors to accompany him as he burst in on the couple and his statement that Eratosthenes was “still lying next to” his wife and that others saw him “standing naked on the bed” were meant to fit the case into the law. Whether it was true is impossible to say, and we do not know the jury’s decision, but Euphiletus had done a good job of maximizing his chances of walking free.

Draco’s laws only limited punishments against men who killed their rivals. Other laws set out the consequences for unauthorized sex by females. Unmarried virgins would see their marriage value diminish in the event of illicit sex, and to recover the loss their fathers were allowed to sell them into slavery—even if the sex had in fact been rape. Married women who committed adultery put their husbands in the position of being required to divorce them or lose their own civic rights. This stipulation was intended to prevent couples from trapping men and extorting payoffs. Women caught in the act were barred from wearing ornaments and participating in religious life: Any citizen had the right to slap around adulteresses who later showed up to sacred ceremonies. Such sanctions were harsh, but far less severe than the death and mutilations faced by adulterous wives under Babylonian, biblical, and Roman law.

5

FISH, VEGETABLES, AND HOT PITCH

Euphiletus took a big chance by killing Eratosthenes. All trials are gambles, and in the rowdy Athenian courts the judgment could well have gone against him. He had other options in considering revenge against Eratosthenes while retaining his honor, such as imprisoning the seducer in his house and ransoming him to his family. He could also have taken Eratosthenes to the authorities for prosecution. Had Eratosthenes denied the charge and been found guilty, he would not have faced execution. Instead, Euphiletus would have been allowed to beat him up in public and ram foreign objects such as spiky scorpion fish and large radishes into his anus. Euphiletus also could have removed Eratosthenes’s pubic hair with hot pitch, or even plucked it out. (One comic poet asked how men “ever manage to fuck married women when, while making their move, they remember the laws of Draco.”)

Severe though the pain might be, the emphasis would have been on degrading Eratosthenes and others like him by making them take on “womanly” characteristics. Depilation was a female practice, so forcing it on a man was to feminize him. It was acceptable for women to submit to anal penetration, but deplorable in the case of freeborn men. These punishments not only bruised the adulterer’s reputation, but also gave the aggrieved husband the pleasure of reciprocating a vicarious sexual attack to settle the matter.

Sparta had no such preoccupations with adultery. Because men there spent so much time with their military units, it was impossible to expect women to remain faithful and still guarantee a steady supply of babies. Marriage was an institution meant to deliver warriors to the state, not heirs to the father. The Spartan government couldn’t care less where a woman’s child came from, so long as the father was a citizen. With that objective in mind, an elderly man was free to ask a young one to deposit “good seed” in his wife, and a healthy man in a barren marriage could impregnate another man’s spouse if the woman’s husband agreed. (Nevertheless, Spartan law encouraged passionate marriages. Husbands and wives were kept apart for long periods to increase desire and make children as energetic as their parents’ lovemaking.)

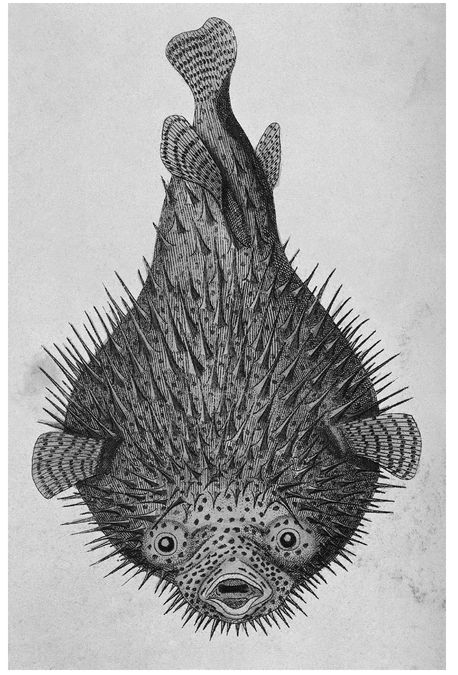

6AN INSTRUMENT OF PUNISHMENT

In ancient Greece and Rome, the husbands of adulterous women had several options for revenge. Most of the punishments allowed a husband to shame his rival by inserting foreign objects, such as spiky fish and radishes, into his anus. ©WELLCOME LIBRARY, LONDON

HOMOSEXUAL LOVE—AND BERRIES

Sex was more of a contest for Athenians than an expression of affection. The partner in the active role prevailed to his masculine glory, while the penetrated one played the woman and was thereby defeated. Somewhere in this harsh exchange was what Plato saw as the highest form of love.

Much of the Greek world was dazzlingly permissive in its attitudes toward homoeroticism and sex between men. From a modern perspective, Greece was an Eden of homosexuality, where male-male affection was prized. Athens’s venerated lawgiver Solon wrote erotic poetry to boys, and the city’s great men openly sought the company of male youths. Taking this view one step further, the United States would only match the tolerance of Athens about three thousand years later, in 2003, when the Supreme Court nullified most American antisodomy laws.

Can we say, then, that the United States has finally begun to follow the ancient Greek example, allowing its millions of gay citizens to take their rightful place as social equals to heterosexuals? Not at all. Even now, a man caught engaging in the type of homosexual sex admired in ancient Greece (i.e., older men taking adolescent boys) will do extensive jail time. If he manages to serve his sentence without being killed by other prisoners, he faces a lifetime of ankle bracelets, residence restrictions, and inclusion on public lists of sex offenders. No one but the most strident of civil libertarians would defend him, much less talk to him. He would be known forever as a pedophile, the worst sort of social deviant.

By contrast, the same-gender conduct decriminalized in the twentieth century by Western courts, that of two adults engaging in “sexual practices common to a homosexual lifestyle,” would have been revolting to most ancient Greeks. “Homosexual lifestyles” as such did not exist, nor did the concept.

Again, the key distinction for the Greeks (as well as for other ancient societies) was in the taking and giving. To be the active partner was to embody male qualities—powerful, principled, in charge. The partner in the passive role was simply female, even if he had a penis. Thus there were no explicit prohibitions against same-sex relations, but, depending on one’s age, class, and position in bed, homosexual sex could be risky indeed. To make the wrong male into a female was a potentially life-threatening gamble, made even more treacherous by the city’s confusing web of laws and customs.

Greek attitudes toward homosexuality resulted in part from a cultural belief in the origins of the sex drive. Plato traced it back to humanity’s initial division into three genders: male, female, and both at once. Originally, humans had two faces, two sets of genitalia, four legs, and four arms each. The original body design of these proto-people worked so well that they grew uppity in the face of the gods, which prompted Zeus to chop them all in two. The result was human beings as we know them: creatures condemned to a lifelong search for their missing halves. Those who came from androgynes craved the opposite sex. Women hewn from double-females sought women, and those cut from double-men were attracted to males. The relief people feel when they conjoin with others in the same lonely condition is a key aspect of what Plato called love.

Plato himself made no secret of his preferences. Those cut from double-males “are the best of their generation,” he said, “bold, brave, and masculine.” Naturally, they had no interest in marrying women, “although they are forced to do this by convention.”

These ideas carried some weight as late as the turn of the twentieth century, when Oscar Wilde referenced

The Symposium to the jury presiding at his first trial for sodomy. In a packed London courtroom, he intoned Plato in defending the “love that dare not speak its name,” describing it as “the noblest form of affection” and stating that “there is nothing unnatural about it.”

7 (See Chapter Eight.)

Not all of Greece agreed with Plato’s ideas, of course, but many Greek communities incorporated male-male sex into their educational systems. In Crete, men symbolically kidnapped boys and took them to the countryside for manly outdoor training. After a few months, the boys were given military kits and welcomed as adults. The process was conducted along strict guidelines, and the boys had a duty to report whether or not their teachers pleased them sexually; if they did not, the boys were permitted to get rid of them.

Spartan boys were entrusted to the care of respected men at the age of twelve. Penalties awaited men who refused to provide such tutelage, or who did so poorly. The relationships were definitely sexual, as attested by the twenty-six-hundred-year-old carved inscriptions still visible on a seaside rock wall in the former Spartan colony of Thera. There, a few dozen meters from the old temple of Apollo, Spartan men brought in expert stone carvers to record their accomplishments: “Here Krimon had anal intercourse with his pais [boy], the brother of Bathycles,” reads one inscription.

Cultures that permitted homosexual sex established regulations as to how and when it could occur, especially in Athens, where young males were protected from unauthorized advances. Slaves suffered fifty lashes for courting free boys or even following them around, and death awaited any man who walked into a school without permission. Those allowed to teach boys were required to be older than forty, when their ardor was believed to have diminished. Athletic coaches were trusted least. According to one source:

A wrestling master, taking advantage of the occasion when he was giving a lesson to a smooth boy, forced him to kneel down, and set about working on his middle, stroking the berries with one hand. But by chance the master of the house came, wanting the boy. The teacher threw him quickly on his back, getting astride of him and grasping him by the throat. But the master of the house, who was not unversed in wrestling, said to him, Stop, you are smuggering the boy.

None of this seems to have stopped the likes of Socrates and the orator-statesman Aeschines from passing days at the gymnasium, where they spent much of their time ogling pretty boys. The temptation was evidently too great.

8

ONCE A HUSTLER . . .

If the idealized union of Greek males was an exchange of sex for learning and social connections, such arrangements were rare. Far more frequent were men and boys selling their bodies for money. These male pornai (prostitutes) hustled the brothels and streets and took all comers, even slaves. Higher-end gigolos were kept by one man or shared among a group. Athenian men, married or not, suffered no penalty or shame for using male prostitutes so long as they were not adults or wellborn. The idea of sex between adult men was especially distasteful, and bachelorhood was avoided.

Prostitutes carried on their trade legally and paid taxes, but were forever barred from participating in public life, including court cases. Many former male pornai presumably kept themselves far enough below the radar to avoid trouble, but not everyone could. In one well-known case, a man rose from a youthful career as a prostitute to the cream of Athenian society, only to have his past return in court decades later and swallow him up. The main issues in Against Timarchus, as the case was known, had nothing to do with whoring. Timarchus’s accuser, the aforementioned Aeschines, happily admitted to being a “nuisance” in the gymnasia and getting into fights over boys. He also had no quarrel with male prostitution per se. He did, however, vehemently object to Timarchus’s right to appear in court against him. In one of legal history’s great “gotcha” moments, Aeschines defeated Timarchus in a major case by exploiting his past as a dockside hustler.

The original question was whether or not Aeschines had sold out Athens in negotiating a peace treaty with an aggressive foreign power. In 347 BC, Athens had sent Aeschines and two other prominent citizens to discuss peace with Macedonia’s King Philip II. The irascible king, best remembered as the father of Alexander the Great, had the better strategic position, and forced Athens into a deal that put it at a disadvantage. The agreement was received badly back home, and resulted in finger-pointing between the diplomats.

The result was a series of court clashes between some of Athens’s most outsized personalities. The orator Demosthenes rounded on Aeschines, but his charges against the latter were grave enough to prompt him to seek the prestigious support of Timarchus, who had already authored one hundred pieces of legislation. Timarchus and Demosthenes accused Aeschines of treason, i.e., taking payoffs from Philip. Everyone on the jury knew the players by reputation, so it must have been quite a shock when Aeschines managed to change the subject from his own alleged corruption to Timarchus’s prior sex life.

Aeschines accomplished this by filing his own suit against Timarchus. He had only a few hours to speak, so he delivered his twenty-thousand-word speech at warp speed, steamrolling the jury with details about how Timarchus had, in his youth, bounced from house to house, giving his “well-developed, young” body to hungry men and even to a slave. “This foul wretch here was not disturbed by the fact that he was going to defile himself,” boomed Aeschines, “but thought of one thing only, of getting [the slave] to be paymaster for his own disgusting lusts; to the question of virtue or of shame he never gave a thought.” A man so weak, so willing to turn himself into a “creature with the body of a man defiled with the sins of a woman,” he said, could neither accuse him of treason nor show his face in court.

Undoubtedly it was the seriousness of the treason charge that made Aeschines strike back so hard. He must also have been concerned that because Timarchus’s wrongdoing had occurred so many years earlier, the jury might be prone to making light of the issue. Whatever the reason, he smeared his opponent as one who had not only done wrong but was, in light of his past, incapable of ever doing right.

The strategy worked. Aeschines won by a narrow margin, and Timarchus later hanged himself. In the fray, the critical question of whether Athens had indeed been sold out to a dangerous enemy was subordinated, at least for a while, to the popular fascination with dirty sex. This was not the last time a public figure’s sex life would be hauled out of obscurity to wreck him politically, but in its scope and effect

Against Timarchus remains a milestone. Prominent men like Timarchus, who lived in the public eye, were probably subject to stricter behavioral standards than the average citizens sitting on the jury. Still, the law forbade all men who “feminized” themselves for money, or who seemed to enjoy it too much, from public life. The defeat of Timarchus was a lesson in caution for all Athenians.

9

FINDING A BALANCE

Given this minefield of punishment and shame, how were male-male relationships to be managed? Could anyone ever have passive sex and still have a civic profile? Not likely, if he was an adult. For a boy it was still risky, as Against Timarchus shows, but possible, if rigid courtship rules were followed.

“A love affair in itself is neither right nor wrong, but right when it is conducted rightly and wrong when it is conducted wrongly,” said Plato. A good male lover was supposed to be “constant” in his feelings, and love the boy’s character as well as his body. When this noble purpose was matched by the boy’s interest in acquiring wisdom, the union was “heavenly.” “[T]hen and then alone is it right for a boyfriend to gratify his lover.”

Homoerotic love was almost a zero-sum equation in which a man’s honor in winning a boy was equaled, potentially, by the boy’s dishonor in being taken. If the boy submitted too readily, he risked being viewed as woman-like or even bestial. If he resisted too much, he stood to lose the sponsorship of an elder who could help him get ahead in the world. His ambition was, in a sense, achieved at the potential cost of his status.

That said, adolescent boys were the main objects of desire for Athenian men, and they did submit. Greek boys (at least those belonging to the elite) were taught to accept sexual intercourse in the same way that respectable Victorian ladies were taught to put up with it: not as a pleasure, but as a duty. It was wrong to be caught quickly, and boys were supposed to maximize their advantages by playing suitors off one another. The cat-and-mouse process bestowed honor on the successful pursuer, and protected the boy.

In almost all other cases, it was ruinous to play the passive role. One vase painting shows a happy Greek soldier, erection in hand, about to sodomize his Persian counterpart—this was not an erotic image; rather, it expressed Persia’s humiliating defeat by the Greeks in easy-to-understand terms. On the home front, comic poets and playwrights had a large reserve of humorous epithets for men who took it from behind. Aristophanes was the peerless leader of those who enjoyed baiting passive homosexuals, repeatedly calling attention to the supposed elasticity of their sphincter muscles and effeminate mannerisms.

Those men who took the laboring oar in anal sex suffered no opprobrium and saw no need to hide their desires. Indeed, the anuses ridiculed with such glee by Aristophanes were also celebrated in poetry as delectable “buds” and “figs.” In a poem by Rhianus, a sweetly oiled “backside” is asked by an anxious lover whom it loves best. The answer—“Menecrates, darling”—is not what the lover wants to hear.

10

DO ASK, DO TELL

One type of homoerotic relationship, praised by Aeschines in Against Timarchus, was the love between soldiers. He celebrated the intense bond between the Trojan War hero Achilles and the younger warrior Patroclus. Theirs was a love that “had its source in passion,” Aeschines argued, and represented everything admirable. Honoring Achilles in a public speech was an easy shot, like extolling the virtues of motherhood today or the valor of a nation’s own troops in battle. It surely came off well, despite its irrelevance to the case. Aeschines was a pompous blowhard, but his references to Achilles and Patroclus underlined the general belief that love and sex among soldiers was something to be emulated, not punished.

Far from barring homosexuality in the military, as the United States famously did in 1942, or embracing a “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy as it did fifty-one years later, Greek societies saw no incompatibility between male-male love and military discipline. As we have seen, pederastic coming-of-age rituals in Crete and Sparta served mainly as preparation for military service. In Thebes, however, the ideal of homosexual warriors reached its apotheosis.

In 378 BC, the Theban army organized an elite unit of 150 pairs of “young men attached to each other by personal affection,” which formed the core of its famed military machine. The group became known as the Sacred Band of Thebes, the descriptor “sacred” most likely deriving from Plato’s

Symposium, in which he refers to a male lover as a divine friend; but Plutarch makes it clear that the Sacred Band was organized for tactical reasons:

For men of the same tribe or family little value one another when dangers press; but a band cemented by friendship grounded upon love is never to be broken, and invincible; since the lovers, ashamed to be base in sight of their beloved, and the beloved before their lovers, willingly rush into danger for the relief of one another.

The pairs of lover-soldiers were, at first, distributed throughout the Theban infantry, but later consolidated into a single fearsome unit. They were undefeated until they and their Athenian allies met up with Philip II and his son Alexander at the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BC. The Athenians were routed, which left the Thebans alone, surrounded, and overwhelmed. Despite certain death, they refused to surrender, and kept fighting until they were annihilated. Rather than cheer his victory by taunting the vanquished soldiers or abusing their bodies, Philip had only respect for them:

[W]hen Philip, after the fight, took a view of the slain, and came to the place where the three hundred that fought his phalanx lay dead together, he wondered, and understanding that it was the band of lovers, he shed tears and said, “Perish any man who suspects that these men either did or suffered anything that was base.”

Thirty-eight years after that battle, the Thebans erected a giant stone lion on a pedestal at the burial site of the Sacred Band. The restored statue still stands as a monument to some of the bravest—and gayest—soldiers ever to fight on the field of honor.

11

DARK PLEASURES, BRIGHT CONVERSATION

However beguiling fifteen-year-old hairless boys might have been to aristocratic men, it doesn’t take long to consume a fig. Callow adolescents could not have been interesting company for men so far beyond them in education and experience. Here women return to the picture, in the form of the hetaerae, that sophisticated class of prostitutes who passed long evenings with the city’s prominent men. (Demosthenes observed that Athenian men kept wives for “the production of legitimate children,” concubines for the “care of the body,” and companions for “pleasure.”) Many of these women stimulated the mind as well as the body—Greek courtesans were known throughout the ancient world for their refinement and ability to match wits with the best minds in Athens. Top-tier courtesans often enjoyed better lives than their clients’ wives.

That many of them survived childhood, much less became beloved companions to the likes of Pericles, spoke to their scrappy ingenuity. Many hetaerae either were the children of prostitutes or were acquired by brothel-keepers after being left to die as babies. If they later showed an aptitude on their backs, they could try to persuade their clients to buy them out and invest in their liberty. Under these conditions, and without the benefit of formal instruction, some managed to learn music, philosophy, and rhetoric.

Hetaerae didn’t have long to make their mark. In a culture even more worshipful of youth than ours today, time was their main enemy. Their prime earning years were often spent laboring as slave prostitutes. By the time they scraped together enough money to purchase their freedom, many had, in the words of the comic poet Philetairos, “rotted away fucking” and were no longer able to command top fees. Facing a decline in earning power, the more enterprising of them became brothel-keepers themselves, buying babies and girls and living off their earnings. This kind of work generated more than its share of litigation.

IN THE EARLY fourth century BC, one married man’s love for an elderly prostitute in his employ caused an inheritance battle. This fellow, Euktmon, was advanced in years himself, and had money, a family, and a number of profitable whorehouses. One of his prostitutes, the well-known Alce, worked at his brothel in Piraeus until she became too old to generate much money. She remained at the house where she serviced a few clients, had a couple of babies, and plotted a way to survive in her old age. First, she convinced Euktemon to let her manage his brothel in the potters’ district of Athens. Then she set out to manage Euktemon himself. Despite his ninety-six years, the records show that he began to spend far more time at the brothel than was necessary to collect the receipts:

Sometimes [Euktemon] took his meals with [Alce], leaving his wife and children and his own home. In spite of the protests of his wife and sons, not only did he not cease to go there but eventually lived there entirely, and was reduced to such a condition by drugs or disease or some other cause, that he was persuaded by the woman to introduce the elder of the two boys to the members of his ward under his name.

When Euktemon’s son resisted his father’s attempt to legitimize Alce’s son, the old man threatened to marry her and recognize her offspring as his heirs. His son decided to cut his losses by agreeing to the legitimization, so long as the boy’s inheritance was limited to a single farm.

12Another lawsuit involved a man who had bought a slave boy from a courtesan named Antigone, but claimed that he was so aroused when he made the deal that he didn’t realize he was being tricked. The purchaser, Epicrates, told the jury that Antigone and her partner in the sale, Athenogenes, convinced him to buy the boy’s brother and father as well, and take on their debts in the perfume business. “It is a trifling amount,” Athenogenes reportedly told him, “counterbalanced by the stocks in the shop, sweet oil, scent-boxes, myrrh ... which will easily cover all the debts.” Epicrates testified that he did not pay much attention to the contract when it was read to him. He could think only of the moment when he would have the slave boy to himself. The sale went through, and Antigone used her portion of the money to buy another child prostitute.

Not long afterward, Epicrates regained his senses and realized that he had taken on more debt than he could pay. He gathered some friends and went to confront Athenogenes. A crowd gathered, a fight erupted, and a lawsuit resulted. At the trial, Epicrates tried to persuade the jury to let him out of the contract. There is no record as to whether or not he was successful, but it does not seem likely that a jury would agree that sexual excitement should excuse a buyer from reading what he signed.

ANTIGONE’S AND ATHENOGENES’S legal problems were nothing compared to the tumultuous existence of the Corinthian hetaera Neaera. The lawsuit Against Neaera describes her fight against accusations that she, a foreigner, had illegally married an Athenian man and fraudulently passed her daughter off as an Athenian citizen. The case, which was at least the third one filed in Athens against Neaera and her husband, threw her entire life open for inspection, covering decades in the sex trade. According to Neaera’s accuser, Apollodorus, she was sold as a little girl to Nikarete, a Corinthian madam with a “good eye” for the earning potential of children. There, in the prostitution vortex that was Corinth (the city lent its name to the Greek verb korinthiazein, meaning “to fornicate”), Neaera was put to work before being physically able to have intercourse, and spent her early years learning how to please men and succeed in the business. To command a higher price, Nikarete marketed Neaera as one of her daughters.

It was tough work, but at least Neaera got to travel. One of the business’s best customers was the famous Athenian orator Lysias (the same as hired by the stepson in Against the Stepmother), who was smitten with Neaera’s “sister” Metaneira. As a gift, he brought Metaneira, Nikarete, and Neaera to the religious festival at Eleusis, where he paid for their initiation into the sacred mysteries of the goddess Demeter.

After about twenty years in Nikarete’s employ, Neaera was sold to two customers as their shared sex slave. The three-thousand-drachma sale price was equivalent to five years’ worth of a laborer’s wages, but the buyers must have figured it was less than paying retail every time they wanted her company. The arrangement worked fine for about a year until the men each decided to get married and lighten their financial burdens. They offered Neaera her freedom at a substantial discount of two thousand drachmae if she left Corinth forever.

This was the chance for which Neaera had been waiting many years. Nothing was going to stand in the way of her freedom, not even the boorish perversions of the man who gave her the money, Phrynion. He brought her to Athens, where he “had intercourse with her openly and whenever and wherever he wished”—outrageous conduct even by local standards. At one banquet, Phrynion allowed everyone present, including slaves, to have their way with her while she slept in a drunken stupor.

Neaera was used to humiliation, but this last act went too far. She waited until the time was right and packed up her clothes, along with some of Phrynion’s household possessions and slaves, and left for Megara to start up her own brothel. The business foundered, but Neaera’s personal life improved when she met the Athenian Stephanos, who agreed to take her and her children back to Athens. Stephanos was kinder to Neaera than Phrynion—their thirty-year relationship implies devotion on his part—but he had a long list of enemies. Once back in town, Neaera began to lure wealthy men to their home for sex, where Stephanos waited to “discover” them in the act and shake down the unsuspecting mark for money.

Their racket continued until Phrynion showed up. He sued Stephanos for receiving both Neaera (whom he deemed a runaway slave) and the property she had nicked from his house. Rather than risk everything at trial, Stephanos agreed to have Neaera return most of the stolen belongings, and further allowed Phrynion to take her home for sex on a set schedule.

Disposing of Phrynion turned out to be the simplest of Neaera and Stephanos’s legal worries. Some years later, Stephanos gave Neaera’s wild-child daughter Phano away in marriage to the sober Phrastor, assuring him that the girl was Athenian. The marriage was a disaster. Phano refused to assume the reserved manner of a good Athenian wife, and was thrown out of Phrastor’s house. He filed a lawsuit claiming he had been defrauded into believing Phano was a citizen, and not the daughter of a Corinthian whore. Stephanos countersued for the return of Phano’s large dowry, but must have realized that he was going to lose the case, and settled. Phrastor kept the money.

Phano moved back home, joined the family extortion business, and sparked more litigation. This time, Stephanos “caught” her in bed with Epainetos, a former client of Neaera’s, and held him in the house until he extracted a promise to pay three thousand drachmae. However, as soon as Epainetos was released he filed suit against Stephanos, claiming that there had been no cause to hold him. Phano was, he charged, no ordinary daughter living in a common Athenian home. Rather, she was a prostitute, and the household a brothel. Again, Stephanos saw that he would be defeated in court, and gave up his claim.

By the time Apollodorus sued Neaera, he had already faced off in court against Stephanos on other matters, and hated him. His lawsuit, which was based on Neaera having passed herself off as a respectable Athenian wife and mother, was admittedly brought out of spite against Stephanos. The fact that Apollodorus was not directly affected by Neaera’s actions didn’t matter; anyone could sue for violations of the citizenship laws. As Apollodorus harangued the jury for three hours, giving all of the details of Neaera’s “service in every kind of pleasure,” the former hetaera must have felt that her luck was running out. If she lost the case, she faced a return to slavery. (Stephanos, moreover, stood to lose his civil rights as an Athenian citizen.) We have no record of the speeches for the defense, nor do we know the jury’s verdict, but it seems well within likelihood that her lifelong jig was up.

13

NEXT TO NEAERA, Athens’s best-known courtesan was Aspasia, the brilliant mistress of Pericles. The great statesman-general’s love for her was open and passionate, to the point that some historians believe he got rid of his wife to live with her. Most marital relations in Athens were arid affairs, but Pericles felt tender affection for Aspasia. “Every day, when he went out to the marketplace and returned, he greeted her with a kiss,” wrote Plutarch. Far from the model of respectable Athenian wives who were supposed to be ashamed even to be seen, Aspasia’s life was lived in public. Even Socrates took his disciples to learn rhetoric from her.

Aspasia had traveled a long way up to breathe the rarefied air of Athenian high society. A native of Miletus, she had most likely come to the city under the usual grim circumstances of foreign-born prostitutes—enslaved and exploited. Eventually she obtained her freedom, setting up a high-end bawdy house that functioned as both a philosophy salon and an urban resort for wellborn men seeking good food and sexual adventure.

Aspasia’s attachment to Pericles was both a benefit and a risk to him. As the case of Timarchus demonstrates, sexual misadventure was a trap for politicians in Athens. Pericles’s many enemies spared no effort in using Aspasia as a way to get to him. She was reviled as the product of sodomy and as a skin trader who filled “all of Greece . . . with her little harlots.” Despite her acclaimed political wisdom, she was also accused of influencing Pericles to act against the city’s best interests. (It was said that she had goaded Pericles into a war with Samos, a rival of her native Miletus.) Aristophanes took these accusations one step further, in satire, supposing that Aspasia had even convinced Pericles to start the catastrophic Peloponnesian War after two of her prostitutes had been stolen by residents of Sparta’s ally, Megara.

Finally, Aspasia was sued on a charge of “impiety,” allegations of which included procuring freeborn girls to satisfy Pericles’s perversions and defiling temples. In a monumentally dramatic scene, Pericles—preeminent man of the city, military and political leader, orator, builder of the Parthenon—went to court personally on her behalf. According to Plutarch, he “burst into floods of tears” before the jury, begging them to acquit Aspasia. The jury complied.

14It is virtually impossible to imagine a present-day political leader pleading with a jury to show mercy to his mistress, much less tearfully acknowledging his love for her. Think of Bill Clinton’s conduct when sued for exposing himself and demanding sex from Paula Jones, an Arkansas state employee. He denied everything, hired top Washington legal talent, and eventually won the case on a procedural technicality. Before that happened, however, he lied under oath about his encounters with another young woman, Monica Lewinsky—a denial that was easily disproved and gave his enemies in Congress a pretext on which to impeach him. That Clinton beat the impeachment and served out his presidency with much popular support only highlights the paradox: Would any of his loyalists, including his wife, have stayed with him had he acknowledged his sexual relationship with Lewinsky or, worse, that he cared for her? Probably not. (The president’s affectionate gift to her of a copy of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass was never explained—with good reason.)

Pericles took a chance by defending Aspasia, but that was not the end of their legal struggles. Their next obstacle arose from a law Pericles had championed years earlier, which denied citizenship to children whose parents were not both native Athenians. Some time after the impiety trial, illness killed Pericles’s sister and his two sons by his first wife. With no living heirs, he asked his countrymen to accept his son by Aspasia as legitimate. The Athenians understood that his misfortunes “represented a kind of penalty which he had paid for his pride and presumption,” and granted his request.

LET’S MAKE A DEAL

As the Classical period in Greece gave way to the more cosmopolitan Hellenistic Age, women with money began to demand more equality from their husbands. For example, a marriage contract between two Greeks in Egypt, dated 311 BC, included the requirement that the husband remain sexually loyal to his wife—at least at home. The bride, Demetria, had some bargaining power: She brought one thousand drachmae worth of clothing and ornaments to the union, which was evidently enough to get her husband, Heraclides, to agree to refrain from doing what Greek husbands had done for centuries:

It shall not be lawful for Heraclides to bring home another woman for himself in such a way as to inflict contumely on Demetria, nor to have children by another woman, nor to indulge in fraudulent machinations against Demetria on any pretext.

The contract had sharp teeth. Had Heraclides broken the deal, he would have been forced to return the dowry and also forfeit one thousand drachmae worth of his own property. He was still allowed to visit all the prostitutes he wanted—he just could not bring them by the house or sap the family’s finances in taking care of his stray children.

Of course, the curb on Heraclides’s freedom with other women did not imply matching liberties for Demetria. Any infidelities on her part were still strictly forbidden under the marriage contract—although it is interesting that the husband felt the need to reaffirm this in writing rather than just rely on the law. However, changes were coming, at least with regard to the number of people who were allowed to control her life. Local law still permitted a father to step in and dissolve his daughter’s marriage at will, but as Egypt came under Roman control, married women would be allowed to defy their fathers’ demands and remain with their husbands.

15Rome, of course, was then transforming itself from a backwater city-state on the Italian peninsula into a territory-gobbling war machine. By the mid-second century BC, it had rolled over Greece and was rapidly Hellenizing itself. The Athenian Greek “phallocracy,” as the historian Eva Keuls so nicely puts it, would mix with Rome’s pagan—and, later, Christian—values to create a long-lasting model for modern sexual regulation.