7

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: REVELATION AND REVOLUTION

OPEN MINDS AND SELF-ABUSE

It was in the eighteenth century that life for many in the West began to resemble life as we know it today: urban, mobile, sexually liberal. All things being equal, if a reasonably capable man of the present time was dropped into a crowded London, Paris, or New York street circa 1760, he could have gotten along without too much trouble. The language of the day was different, but not incomprehensible. The streets were full of trash and manure, but at least a few were paved. There were mass-produced iron goods in shops and people wore cloth woven in mills. They spoke less about the Lord above than about money on earth. For a growing number of people, heaven no longer meant paradise after a life well lived; rather, it signified material abundance and physical pleasure in the here and now. If our time traveler were to enter a tavern and strike up a conversation, he would find common ground for chatter. If he were interested in finding sex, it would be likely to be available in the alehouse’s back rooms, or close by.

The age of the American and French revolutions began to push God out of the legal business. By century’s end, many countries looked to “reason” and to the “people’s will” to guide the law. The world was no longer just the product of divine effort, nor was human suffering due to heavenly vengeance. When the new generation of “enlightened” men looked to the night sky, they saw mathematical equations. When they gazed at the mountains, they saw coal for burning in factories. And when they felt familiar stirrings in their breeches, the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit were the last things on their minds.

The transition from religion to reason was patchy and disorderly. France decriminalized sodomy during its revolution—a giant advance in sexual freedom by any measure—but by 1806, England was still putting more sodomites to death than murderers. At the same time, while King George III was warning that divine wrath follows immorality, British publications such as The Whoremonger’s Guide to London brimmed with adverts for ladies of every description, talent, and price. Some brothels offered women of utmost refinement; others catered to men wanting to be whipped and choked in dungeons. There were paid shows featuring “spotless virgins” copulating onstage, and free peeks could be stolen of couples doing it in the streets and parks. (The rake and diarist James Boswell personally consecrated the new Westminster Bridge by having sex with a “strong jolly damsel” beneath it.) Sex was everywhere, in the open, and in the glow of the new philosophy of the Enlightenment it was natural, reasonable, and right.

The decline of religion sometimes took rather bizarre forms, as when Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris was converted into a “temple of reason” in 1793 (the year after the decriminalization of sodomy), and a showgirl was crowned “goddess” of reason and liberty at the cathedral’s altar.

1 In such cases reason became shorthand for hatred of the church and all it represented, but just as often, reason and science were co-opted to justify traditional Christian morals. The problem was that eighteenth-century science was often quite wrong—witness the panic over masturbation. In 1760, the respected Swiss physician Samuel Tissot published

L’Onanisme, a blockbuster that characterized masturbation as a form of slow suicide. Tissot and his ilk blamed dozens of maladies on the world’s oldest pastime. Masturbation, they said, resulted in an irretrievable loss of semen, “the essential oil of the animal liquids.” If done with frequency, men were warned, sexual self-abuse depleted the body to the point of madness, illness, and death.

Tissot’s obsession with the subject started in 1757 after he learned of a young watchmaker who, the doctor said, masturbated as often as three times per day, resulting in a loss of semen so excessive the man grew fearful for his life. Tissot wrote that upon learning of the case he ran to the man’s bedside:

[W]hat I found was less a living being than a cadaver lying on straw, thin, pale, exuding a loathsome stench, almost incapable of movement. A pale and watery blood often dripped from his nose, he drooled continually; subject to attacks of diarrhea, he defecated in his bed without noticing it; there was a constant flow of semen; his eyes, sticky, blurry, dull, had lost all power of movement; his pulse was extremely weak and racing, labored respiration, extreme emaciation, except for the feet, which were showing signs of edema. Mental disorder was equally evident, without ideas, without memory . . . Thus sunk below the level of a beast, a spectacle of unimaginable horror, it was difficult to believe that he had once belonged to the human race.

Tissot arrived too late to rescue the patient and the experience rattled him deeply. He was already steeped in antimasturbation literature, and troubled by the weakness he had observed in his own self-pleasuring patients, but it was the sight of the watchmaker’s hideous state that brought out his true calling: “I felt then the need to show young people all the horrors of the abyss into which they voluntarily leap.” He sat at his desk and started to write.

What emerged was a book that used “science” instead of the Bible to justify old-time sexual repression. Masturbation not only violated God’s commandments, it was now labeled as medically harmful. Semen was stuff to be conserved, husbanded, and hoarded. Without an ample supply, the body slowed down and eventually stopped, as dozens of Tissot’s gruesome case studies supposedly showed. L’Onanisme was an instant hit and made Tissot famous and wealthy. The book quickly became a standard reference work and was translated into English, German, Italian, and Dutch. Tissot became the first major standard-bearer for the 150-year period ending just after World War I, which has been called the age of “masturbatory insanity.” A terrified masturbator wrote to Tissot in 1774: “Sir, you are the benefactor of mankind; please be mine as well.” The good doctor must have been only too happy to oblige.

THE RAVAGES OF SELF-ABUSE

Starting in the eighteenth century and continuing for at least 150 years, prevailing science held that male masturbation wasted the body’s essential fluids, resulting in sickness, insanity, and sometimes death. This illustration, from 1845, depicts a man in the “last stages” of exhaustion from “self-pollution.” Meanwhile, sales of pornography were soaring.

© WELLCOME LIBRARY, LONDON

NOWHERE DID THE masturbation scare strike as hard as in Germany. A cadre of antimasturbation crusaders emerged, driven by the belief that increasing numbers of males and especially schoolboys were killing themselves. Everywhere they looked, they saw youths rubbing their crotches against trees, arousing themselves on horseback, and even stroking their privates in the classroom under long coats. Those boys who could not be frightened into stopping were sometimes put into mental hospitals or even infibulated—that is, their foreskins were tied shut over the head of their penis and held fast with iron rings. Later preventive devices, used everywhere, were no less crude. Right up to World War I, the U.S. government granted patents for contraptions that restrained, electrically shocked, and pierced penises with the temerity to become erect, even during sleep.

It is unclear whether many males were actually deterred from masturbating. In 1799, one influential German schoolmaster claimed success: “Thousands of young Germans, who ran the risk of ending their abject lives in a hospital, have been saved, and today devote their restored energies to the good of humanity.” That statement seems rather optimistic. Most boys and men, even if they were frightened at first, must have discovered that the horror stories simply didn’t pan out. Indeed, judging by the high consumption of pornography at the time, it appears that males everywhere were wasting their fluids in volume.

2Most eighteenth-century masturbators did their business when no one was looking, of course. Not so among the five-hundred-odd members of the secret Scottish Beggar’s Benison society. Strict custom in the centuries-old club required initiates to sit alone in a room and obtain an erection while society members stood in a circle in a nearby chamber. Upon the blowing of a penis-shaped horn, initiates walked into the main room and placed their penises on a pewter “test platter” for the group to inspect and touch with their own genitalia. If all went well and the novitiate was approved, the group would welcome their new brother with the pledge “May your prick and your purse never fail you” and enjoy an evening of bawdy fun with prostitutes. To further cement ties among group members, the test platter and various silver receptacles would be brought out for them all to masturbate upon.

The men of the Beggar’s Benison society were respectable businessmen and magistrates. While they shared an interest in raucous drinking, whoring, and masturbating, their approach to their wives was quite another matter. Current mores encouraged the enjoyment of marital sex, but it was something to be managed along rational lines. For sober guidance in this regard, there were a number of manuals available throughout the United States and Europe, most notably Aristotle’s Masterpiece (published anonymously and having nothing to do with the Greek philosopher) and Nicolas de Venette’s Tableau de l’amour conjugal (Conjugal Love). These books, endlessly reprinted and cannibalized, picked up on the pseudo-scientific tone of the age to instruct married couples how, when, and why to make love. Aristotle’s Masterpiece went through forty-three editions by 1800. Conjugal Love was still in print in the 1950s.

De Venette echoed Tissot’s warnings about the dangers of excessive loss of semen, especially the risk of brain damage. At the same time, he taught that females demanded regular doses of semen to prevent their wombs from rotting and their minds from becoming frenzied. Both de Venette and “Aristotle” agreed that sex was required for a woman’s health. Even more important, unless a woman experienced orgasm during sex her own “sperm” did not flow and conception was impossible. It was therefore important for the husband to make sex pleasurable for the wife, so long as the goal was preparing her to conceive. (This belief also influenced rape law over the years, as judges often concluded that a pregnancy was proof that the woman enjoyed sex with the accused offender, and therefore no force was involved. See Chapter Four.) A later version of

Aristotle’s Masterpiece also sets out some encouraging verses at the end of each chapter. Chapter Three, for example, provides the following thoughts for a newlywed husband to express to his panting wife:

Now, my fair bride, now I will storm the mint

Of love and joy and rifle all that is in’t.

Now my infranchis’d hand on ev’ry side,

Shall o’er thy naked polish’d ivory glide.

Freely shall now my longing eyes behold,

Thy bared snow, and thy undrained gold:

Nor curtain now, tho’ of transparent lawn

Shall be before thy virgin treasure drawn.

I will enjoy thee now, my fairest; come,

And, fly with me to love’s elysium;

My rudder with thy bold hand, like a try’d

And skilful pilot, thou shalt steer, and guide

My bark in love’s dark channel, where it shall

Dance, as the bounding waves do rise and fall.

Whilst my tall pinnace in the Cyprian streight,

Rides safe at anchor, and unlades the freight . . .

Perform those rites nature and love requires,

Till you have quench’d each other’s am’rous fires.

De Venette suggested that the man always be on top because that was the best position for conception. Other coital positions, such as woman-on-top, risked producing “dwarves, cripples, hunchbacks, cross-eyed or imbeciles.” Aristotle’s Masterpiece instructed the husband, after lovemaking, “not to withdraw too precipitately from the field of love, lest he should, by so doing, let the cold into the womb, which might be of dangerous consequence.” The wife should sleep on her right side and avoid coughing, sneezing, or even moving. Intercourse was to be repeated “not too often,” otherwise the husband would “spend his stock” before conception was achieved.

The sex manuals’ focus on reproduction excluded other kinds of lovemaking. Pleasure for its own sake had no place in the biologically balanced marital chamber. Yet fewer people than ever were living their lives that way. Sex, conjugal and otherwise, was increasingly seen as part of the natural order of the world, like the tides, and it was happening everywhere in every possible permutation. The law’s task was to balance the weight of fifteen hundred years of restrictive moral teachings with society’s carnal demands. The results were anything but neat.

3

FEMALE LOVE AND LEATHER MACHINES

Can two women love each other sexually? Eighteenth-century morals said no, at least where the females involved were respectable. Among the better classes, lesbian relations were impossible to imagine. Good women could love and embrace each other, sleep together, and write each other passionate letters; all that was noble. But loving and making love were entirely different matters. Unless they were gratifying their husbands, women of “character” were imagined as sexually numb creatures. British judges allowed that females of “Eastern” or “Hindoo” nations might act differently, but not the women of the “civilized” world.

When Marianne Woods and Jane Pirie, the unmarried comistresses of a tony Scottish boarding school for girls, were accused in 1811 of “improper and criminal” conduct with each other, every single student in the school was removed by their parents. Woods and Pirie were ruined overnight. Their primary accuser was a student, the Indian-born grandchild of Dame Helen Cumming Gordon. The girl, who had shared a bed with Miss Pirie, told Dame Gordon that she had been woken up by Miss Woods climbing on top of Miss Pirie and “shaking” the bed. “Oh, do it, darling,” Miss Pirie reportedly said as they rolled around together in “venereal” bliss. The girl further reported that the two women cooed as their bodies made the sounds of a “finger [in] the neck of a wet bottle.”

Dame Gordon sent out letters telling parents that their children were in “grave danger,” and that was it for the school. Pirie and Woods filed a libel suit against Gordon to recover their lost life savings, if not their reputations. Hundreds of pages of trial transcripts later, the two women won, not because they did not sleep together or love each other intimately—they did—but because the judges could not accept that two hardworking, middle-class women such as these could possibly have had sex with each other.

The court saw the stakes as much greater than the personal fortunes of two schoolmarms. For one of the three judges, Lord Meadowbank, the case implicated all well-behaved British women. A world in which women satisfied themselves without need of men was impossible to entertain: “[T]he virtues, the comforts, and the freedom of domestic intercourse, mainly depend on the purity of female manners, and that, again, on the habits of intercourse remaining as they have hitherto been—free from suspicion.” As men carried both the sexual machinery and the urge, it was easy for the court to infer that sex would result whenever a man was in bed with another:

If a man and a woman are in bed together, venereal congress would be presumed. And perhaps, even if a man and a man are in bed together without necessity, an unnatural intention may often be inferred.

But that is where Lord Meadowbank drew a bright line. “A woman being in bed with a woman, cannot even give the probability of such an inference. It is the order of nature and of society in its present state. If a woman embraces a woman, it infers nothing.”

Pirie and Woods admitted that they slept together often, as many people did, and that their “shifts” had been raised in bed, but nevertheless they claimed to have no idea of what Dame Gordon was accusing them of really doing. The court knew, but it refused to go there. In our time, no one would believe that the relationship between Pirie and Woods was asexual. In Lillian Hellman’s 1934 Broadway stage adaptation of the story, The Children’s Hour, a physical relationship between the two women (cast as mistresses of a snooty New England boarding school for girls) was strongly implied, so much so that the play was banned in several cities. Hellman stressed the viciousness of the young accuser in making the lesbianism charge, and also had the two women deny any sexual contact, but the intimate nature of the relationship was what drove the drama. Without the strong whiff of lesbianism, the play would have been puerile and unrealistic. (To appease censors, the 1936 Hollywood film based on the play was recast as a heterosexual love triangle, although a 1961 remake featured the lesbian relationship intact.)

Hellman came along more than two hundred years after the fact. The critical point that drove the court’s decision in the Pirie/Woods case was the conviction that women could not have sex with each other

as women, meaning that some phallus had to be put to use. Without such a device, sex was as likely as “murder by hocus pocus.” “Gross immorality” might result from two females sharing a bed together, even “licentious buffoonery,” but without the involvement of something resembling a male, there was nothing illegal to it. Some women, the court allowed, were “peculiarly organized” as hermaphrodites for quasi-male sex—but that was the kind of thing that occurred in Africa or the exotic East. The historical use of dildos was also examined by the court, but there was no proof of that in this case. Pirie and Woods were not, in any event, the sort to do anything like that, the court felt. “I have no more suspicion of the guilt of [Pirie and Woods],” said another of the judges, “than I have of my own wife.”

4The result of the Pirie/Woods case would have been different had one of them assumed a male role, either by wearing men’s clothing or using a penis substitute. In that case, any judge in England would have found a way to punish them severely. In 1746, Dr. Charles Hamilton was convicted in Somersetshire (now Somerset) on charges of fraud and vagrancy for impersonating a man. As widely reported at the time, Hamilton was in fact a woman named Mary Hamilton. For the offense of deceiving another woman into marrying and having sex with her, Hamilton was publicly whipped until her back was “almost flayed” and then sent to prison for six months.

Her criminal life had begun in her teens, when she fell in love with a neighbor girl. The romance ended when the girl became involved with a man and married him. Inconsolable, Hamilton sought a change of scene and identity. She moved to Dublin, where she set herself up as a male Methodist teacher and courted local women. When she was about eighteen, she won the affections of a sixty-eight-year-old cheese seller’s widow. The couple married, and she continued to play the role of a man “by means,” in the words of one contemporary writer, “which decency forbids me even to mention.” The wife’s discovery that her young husband was a woman caused a predictable row, resulting in Hamilton fleeing town with a pocketful of the woman’s money.

Further adventures landed Hamilton in Wells, Somersetshire, where she assumed the male doctor’s identity and began a romance with Mary Price, a naïve eighteen-year-old girl. A two-day courtship resulted in a two-month marriage. Hamilton apparently used a dildo to satisfy Price, as “he” had likely done with other female bedmates. The marriage was sexually satisfying for Price, and might have gone on indefinitely had Hamilton not been recognized by an old acquaintance and denounced. Price tried to defend her husband’s manliness, but ultimately she had to admit that she had been deceived. Her neighbors laughed at her and pelted her with dirt.

Hamilton may have been a cad—there was word she had deceived fourteen women into marrying her—but English law did not explicitly punish female sodomy. Henry VIII’s buggery statute of 1533 dealt only with sexual relations among men or between men and beasts. Women weren’t mentioned. But gaps in the rules have rarely stopped prosecutors from finding something on which to hang a charge. The authorities went after Hamilton under the vagrancy laws for “having by false and deceitful practices endeavored to impose on some of his Majesty’s subjects.” The case against her was strengthened by the discovery of an object of a “vile, wicked and scandalous nature” found in her trunk. Most likely some kind of dildo, it was used as evidence of the means by which Hamilton “entered” Mary’s body “several times.” Hamilton was given the maximum punishment the vagrancy laws allowed. By assuming a sexually aggressive male identity, she had usurped the male prerogative of penetration, considered the essence of the sex act.

5

AROUND THE SAME time the Hamilton scandal was unfolding, a dirty little pamphlet was published about Catherine Vizzani, a female transvestite in Italy. The pamphlet’s English translator was England’s greatest pornographer, John Cleland, who well knew what the public wanted to hear. As Cleland retold the story, Vizzani had also begun donning men’s clothes at an early age, and “incessantly followed the wenches” with “barefaced and insatiable” energy. To affirm her position as an accomplished male rake, Vizzani even sought medical treatment for venereal disorders purportedly caught from “infectious women.”

Taking the name Giovanni Bordoni, she finally won the love of a wellborn young woman and ran off with her to Rome to get married. They were overtaken en route by a chaplain sent by the girl’s uncle to halt the union. Everyone drew their guns, but Vizzani quickly decided it would be safer to give herself up. She was mistaken: The chaplain took Vizzani’s gun and shot her anyway. She ended up in a number of hospitals, where her gunshot wound became infected. As her fever grew, she lost control of her senses and took off the cylindrical “leathern contrivance” she kept strapped “below the abdomen of her detestable imposture.” A few days later, at twenty-five years old, Vizzani died.

The discovery of Vizzani’s “leathern” machine was shocking. Hospital staff members tore the device open. They also examined Vizzani’s body and discovered, to their amazement, that she was not only a woman but a virgin, “the hymen being entire without the slightest laceration.” Soon a formal autopsy was performed, according to Cleland’s account, which resulted in an even more confounding discovery: “The clitoris of this young woman was not pendulous, nor of any extraordinary size . . . on the contrary, hers was so far from the usual magnitude, that it was not to be ranked among the middle-sized, but smaller.” Without any kind of deformity to explain Vizzani’s “unnatural desires,” the surgeon was stumped. The young woman died before legal proceedings could begin, although the local populace’s opinions about her may have led authorities not to charge her at all. A fair number of townspeople thought her protection of her virginity “against the strongest temptations” qualified her to be a saint.

6Early Modern Germany’s sex laws admitted no ambiguity: “Female sodomy” had been an explicit capital crime since 1532. While the law was not often enforced, the threat of the death penalty was real. That was the fate of Catharina Linck, burned in 1721 for living as a man with her young wife, Catharina Mühlhahn.

Before becoming a husband (and an abusive one at that), Linck had been a preacher and a soldier in three armies, among her other personae. Court records from Saxony, where she was tried and executed, reflect the difficulties the judges faced in dealing with a young woman who already assumed no fewer than nine separate male identities.

Linck had grown up in an orphanage, and left it dressed as a young man “in order to lead a life of chastity.” She soon fell in with an ecstatic Christian cult given to hitting their heads against walls and speaking in tongues. For two years, Linck traveled with the group as an itinerant preacher and soothsayer, though her predictions did not always materialize—when she urged two men to walk on water and they sank, she fled. She became a swineherd, and later joined the army of Hannover as a musketeer until her desertion three years later.

Next came a stint in the Polish army. Her regiment was captured by French troops, but she managed to escape imprisonment. Her subsequent hitch with the Hessian army lasted about one year. Linck had by now fashioned a leather penis for herself, to which she appended two stuffed testicles made from a pig’s bladder. The contraption, held in place with a leather strap, served her well: She used it on a string of young girls, widows, and prostitutes.

Tiring of the military life, Linck reinvented herself as a dyer of fine clothes, met Mühlhahn, and married her. During the wedding, someone called out that Linck already had a wife and children, but she produced a document and two witnesses to prove the allegation false. The newlyweds moved in together, and Mühlhahn would later report that their sex life was active and satisfying, despite the pain she sometimes experienced on account of Linck’s large phallus. Their life together out of bed was less successful. Money was always tight, and before long they were begging. Linck also beat Mühlhahn frequently.

One night, as Linck slept, Mühlhahn took a closer look at her husband and discovered the leather truth. Linck awoke and begged Mühlhahn to keep her secret. Mühlhahn agreed, though she demanded that Linck no longer “tickle” her with the device. Finally, Mühlhahn’s mother, who had already suspected that her boorish son-in-law was in fact a woman, could bear the union no longer. With the help of another woman, she attacked Linck, tore off her trousers, and confiscated the ersatz genitals, which ended up in court as critical evidence.

Linck’s defenders did not let her go to her death before making some creative legal arguments. First, they asked, didn’t the Bible only proscribe unnatural acts between women and animals? Moreover, could there be sodomy without semen? But the court was not swayed by such fine distinctions: “The vice is the same for all,” the judges pronounced, even if women only engaged in “bestial rubbing and sexual stimulation of their lewd flesh.” The court ruled that the penalty was death by fire under both divine and secular law, as both male and female sodomites induced God to rain fire and brimstone down upon the earth. Linck was duly executed. The “simple-minded” Mühlhahn was jailed for three years, and then banished.

7

MISS MUFF AND INSPECTOR FOUCAULT: MALE HOMOSEXUALITY ON TRIAL

The Linck case was the last lesbian execution in Europe. Male homosexual conduct would still be punished throughout the eighteenth century, sometimes with execution, but few men seemed to feel an immediate threat. Across Europe and the American colonies, a sprawling homosexual subculture emerged, with no apology. Bars, private clubs, and public cruising zones popped up everywhere, making male-male sexual behavior a visible element of town life. Homosexuality was no less ridiculed than before, and it was still illegal, but its presence was grudgingly tolerated by enough people that it remained in the public eye. Given what we have seen of antihomosexual persecutions over the centuries, and the readiness of people to associate homosexuality with heresy and witchcraft, this was a major advance in itself.

In Stockholm, men met for quick sex in urinals and parks. In The Hague, they signaled each other by stepping on each other’s feet, grabbing arms, or waving handkerchiefs. Amsterdam cruisers prowled the city’s town hall. Elsewhere, men underwent elaborate rituals in private sex clubs. A group in Haarlem met at night in a forest to choose a “king,” while an order of Parisians required initiates to kneel, kiss clusters of false diamonds, and swear fidelity to the others. The more elaborate London clubs, called “molly houses,” after the word then used to describe homosexuals, were run by men with names such as Miss Muff, Plump Nelly, and Judith. New members were also given female names, and often married in chapels. The couples would then retire to a nearby chamber and conceive make-believe children, who were then “delivered” in birthing rooms while the group attended with towels and basins of water. In one 1785 raid near the Strand, police found several such “mothers” attending their newborn “children.” So well did one of them play the role that authorities were convinced that he was genuine and left him alone with his child—a large doll. For men who could not find a willing husband, male prostitutes were always available.

None of this went unnoticed by the state. By the mid-1720s, at least twenty known molly houses were under investigation. The problem for authorities, at least in London, was that there were few police available to make raids. The constables and justices who were on hand often took money from criminals and bawds. One magistrate in Wapping rented his own home to prostitutes. During this period the city’s population was also growing very rapidly. The poor migrants clogging the streets provided new fodder for sex-seekers with money. The church courts, once powerful players in morals enforcement, were now weak. Secular authorities, to the extent they cared, were overwhelmed.

8Enter the Holy Rollers. Starting in the late 1600s and lasting for about four decades, a number of groups labeled, collectively, the Society for the Reformation of Manners financed a series of vigilante police actions against behavior deemed immoral, especially among the lower classes. The society was managed by wealthy prigs and members of Parliament, with one overriding objective: Spend what was necessary, pay anyone off, use any deception, so long as sexual vice was stamped out in the process. To accomplish this, the society paid informants to infiltrate pockets of sin and then further paid constables and magistrates to arrest and charge people with whatever crime might apply. As lawsuits were costly, the society provided the funds to move the cases through court. For at least a time, the strategy bore fruit: About one hundred thousand people were prosecuted.

THE QUACK DOCTOR

From the eighteenth century onward, “science,” of both the legitimate and the quack varieties, exerted a profound influence on sexual mores and law. Here, a doctor is rebuked by a nobleman for failing to cure the venereal disease he gave to a young girl. Often the remedies for syphilis and other sexually transmitted infections were more harmful than the diseases.

©THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

Most victims of society purges were hit with garden-variety charges of lewd and disorderly practices such as street soliciting, indecent exposure, and open-air intercourse. However, the society had a special place in its spleen for male sodomy, which it pursued with intensity. Its first antihomosexual triumph was against Edward Rigby, a navy captain. In 1698, Rigby made the unlucky choice of cruising nineteen-year-old William Minton, who was in the personal service of a member of the society. Rigby approached Minton in St. James’s Park during a crowded fireworks display and pressed his erect penis into the young man’s hand. Minton could not have been too disturbed by Rigby: He promised to meet him a few days later at a tavern. Nevertheless, Minton had second thoughts about the rendezvous. He told his master and soon agreed to work with the society to trap Rigby into an arrest.

Minton met Rigby at the appointed time, in one of the tavern’s back rooms; a constable and four other society members were stationed in the adjoining chamber. Rigby had arrived in a state of high arousal. He told Minton he had already ejaculated in his pants, but was ready for more play. Minton must have seemed hesitant, because Rigby jumped in his lap and begged him for attention, telling him that everyone from Jesus Christ to Peter the Great had had sex with men. Rigby had managed to get inside Minton’s pants and had “put his finger to Minton’s fundament” when Minton grabbed Rigby’s erection and screamed: “I have now discovered your base inclinations!” As the two men scuffled, Minton cried out the signal word “Westminster!” to the officers listening next door. They rushed into the room and took Rigby away.

The captain’s conviction for blasphemy and attempted sodomy was a public relations triumph for the society, though Rigby never served out his prison sentence. (After three stints in the pillory, he escaped England to join the French navy.) For its part, the energized society continued to entrap mollies, eventually pulling off its biggest bust ever against a well-known molly house run by a woman known as “Mother Clap.” Wedged in between an arch and the Bunch o’ Grapes Tavern, Mother Clap’s establishment was a kind of molly fantasyland. Its main room was big enough to accommodate dozens of dancing, singing, and drag-wearing men at one time. One society informant described a Sunday night scene in 1725 accordingly:

I found between 40 and 50 men making Love to one another, as they call’d it. Sometimes they would sit on one another’s Laps, kissing in a lewd Manner, and using their hands indecently. Then they would get up, Dance and make Curtsies, and mimick the voices of Women . . . Then they’d hug, and play, and toy, and go out by Couples into another Room on the same Floor, to be marry’d, as they call’d it.

In addition to a wedding chapel, Mother Clap provided her clientele with a variety of bedrooms. While she did not serve alcohol (technically, the joint was a coffeehouse), the Bunch o’ Grapes did, and the spirits never stopped flowing.

Mother Clap’s club was successful, but not unusual. There were dozens of similar establishments in London, many of which operated in the open without bothering to pay off law enforcement. To the society, the very existence of the molly houses was an outrage, but pulling them down required much more planning than the Rigby operation. Society members needed to secure the cooperation of insiders—hustlers willing to turn in their friends and acquaintances—and gather evidence. Typically, their informers would take constables on fact-finding tours of molly houses.

During one such adventure in 1725, Constable Joseph Sellers accompanied the known sodomite Mark Partridge to several molly houses, where Sellers played the part of Partridge’s “husband.” One stop that night was the Tobacco Rolls alehouse in Drury Lane. There, an orange-monger nicknamed “Orange Deb” approached Sellers and, as Sellers described it to the court, “put his Hands into my Breeches thrust his Tongue into my mouth swore that he’d go 40 Mile [to] enjoy me.” Orange Deb begged Sellers to “go backward and let him,” which could mean that he wanted to either bugger Sellers or simply go with him to a backroom. Sellers refused, in either event. Orange Deb then offered to place himself “bare” on Sellers’s lap, at which point Sellers lost interest in maintaining his cover. He grabbed a red-hot poker out of the fireplace and threatened to “run it into [Orange Deb’s] arse.” In a later trial, three men testified that Orange Deb was a good man with a wife and child and never acted inappropriately. The jury disagreed and sentenced him to stand in the pillory at Bloomsbury Square as well as to prison time.

Partridge also helped the society take down Mother Clap, along with two prostitutes named Thomas Newton and Edward “Ned” Courtney. With their help, the constables had enough evidence to show up on a Sunday night in 1726 and round up about forty people, including Mother Clap herself. No one was caught actually having sex (although some of the men had their pants down), but the abundance of informants made that kind of evidence unnecessary. The first of several trials resulting from the raid sent three men to die simultaneously by hanging on a triangular gallows. As ghoulish as that sight must have been, the executions were outdone by another capital punishment at the same time and place. A woman named Catherine Hayes, convicted of murdering and dismembering her husband, was meant to be strangled just before being set alight, but the flames jumped too high and too fast for the executioner to do his job, and she was left to burn alive. Hayes’s screams were horrifying, as was the sight of her eyes melting away in the heat. Nor was that the only mishap of the day: More than 150 spectators who had paid to watch the executions from viewing stands fell to the ground in a heap when the stands collapsed, and six people died. Mother Clap was convicted in a later trial and sentenced first to the pillory and then to two years in jail. It is unlikely she survived long enough to serve her jail time, though. The newspapers reported that she was treated with so much “severity” by the crowd while in the pillory that she “swooned away twice and was carried off in Convulsion Fits.”

The raids on molly houses stirred their share of public outrage, but so did the underhanded methods used by the society. Its association with lowlife informers such as Newton and Partridge never sat well with many people, nor did the fact that the constables it employed continued to take payoffs, especially from prostitutes. At best, society members were thought of as well-meaning busybodies; at worst, they were reviled as corrupt and vicious. By 1738, the society had lost its luster and was out of business.

9The Netherlands also had a large homosexual subculture, but the state’s methods of dealing with sodomy made even less sense than England’s. In 1730, for the first time in Dutch history, homosexuals suffered heavy state persecutions—a tragedy repeated in 1764 and 1776. In each blast of trials, the confessions of men who were more or less accidentally arrested snowballed into waves of imprisonments and executions, reaching a frenzy toward the end of the century.

In 1764, the drunken Jacobus Hebelaar was drawn to two men urinating in an Amsterdam street. He sidled up, urinated himself, and tried to make a sexual connection with the smarter-dressed of the two. After being told to bugger off, he went to a public toilet under a bridge, where he robbed a man of his money, cufflinks, clothes, and corkscrew. He was arrested shortly afterward by the men at whom he had made a pass earlier in the evening. As luck would have it, they were both in law enforcement. Hebelaar was executed, but not before confessing that for the prior seven years he had committed “the gruesome sin of sodomy” both actively and passively. Moreover, he named his accomplices. Only his robbery was publicly mentioned in connection with the execution, however, most likely to avoid tipping off his sex partners that the police were on their tails. Within one year, seven men were executed, five imprisoned, three exiled, and sixty-four sentenced by default. More than one hundred men had fled the city or committed suicide, all because of Hebelaar’s unsuccessful effort to have sex with a policeman.

It is likely that neither Hebelaar nor his accomplices had the money or influence to arrange special treatment for themselves; power and position generally granted immunity from sodomy laws. In Prussia, protection from prosecution for those with means was almost complete. King Frederick II (whose own sexuality was ambiguous, to say the least) wrote that in his state there was freedom of “conscience and of cock,” but those words did not translate into action for the lower classes. Typical were the multiple acquittals of Baron Ludwig Christian Günther von Appel for sodomizing his farmhands. One of the baron’s accusers was flogged and assessed court costs. Two years later, another farmhand, Jürgen Schlobach, claimed that the baron had “twice stuck his member in his rear and once in his mouth; he’d gotten gooey and had to rinse out his mouth at the fountain.” Schlobach was flogged and banished forever from Prussia. As the whipping began, Schlobach’s father and brother attacked the flogger with pitchforks, which brought them prison sentences of their own. Schlobach’s mother was also jailed after she accused the baron’s wife of trying to buy her silence with a new dress.

10

FRANCE, AS USUAL, cut its own path, suffering neither the vigilante purges of England nor Holland’s crazed persecutions. Rather, there was a great deal of police surveillance and record keeping. Sodomy remained a capital offense in France until 1791, and about forty thousand suspected homosexuals were catalogued by special sodomy patrols over the course of the century. However, very few sodomites were executed or even publicly punished. On the contrary, authorities often tried to downplay publicity for fear that spotlighting homosexuality might make it contagious. As elsewhere, those in high places could usually flout the antisodomy laws if they were discreet. The hoi polloi could count on some jail time or even banishment, but even the upper classes were not entirely safe if their sexual adventures were conducted too openly.

One summer night in 1722, among the trees and fountains surrounding the royal palace at Versailles, several young noblemen had sex with each other. The gardens, covering nearly two thousand acres, were certainly big enough for them to find a discreet spot, but they chose instead to have their fun within a stone’s throw of the palace—so close, in fact, that several people heard and saw them going at it. Although accounts differ, it seems there were at least six men involved, almost all of them recently married. In the words of a lawyer at the time, the men were not committed to sex only with their own gender; they simply enjoyed “butt-fuck[ing] each other” under the moonlight and “rather publicly.” When questioned about their escapades, none of them were contrite, nor did they have reason to be scared for their lives. Most of them were “exiled” to their comfortable estates, later to be joined by their wives. Only one was sent to the Bastille.

When the twelve-year-old future king Louis XV asked why some of his courtiers had been sent away, he was told that they had been tearing down fences in the gardens. Just two years later, Louis (who by then had been crowned) became too involved with the young Duc de La Trémoille, dubbed the “first gentleman of the King’s bedchamber.” For making a “Ganymede [i.e., a rear-end receptacle] of his master,” Trémoille was quickly married off and exiled. Louis was sent on a hunting trip to build up his manly tastes and lose his virginity. He seemed to prefer hunting, however, and—at least then—showed little interest in females.

By 1725, many felt that aristocratic homosexual behavior had gotten out of hand. “All of the young noblemen of the court were wildly addicted to it, to the great distress of the ladies of the court,” said Edmond-Jean-François Barbier, a Paris lawyer of the day. Additionally, it was believed that this “aristocratic vice” was spreading to the lower ranks. There “is no order of society, from dukes on down to footmen, that is not infected,” wrote the lawyer B.F.J. Mouffle d’Angerville. This belief was both absurd and late. Paris was already crawling with cruising spots and meeting places that catered to homosexuals from every level of society. No one on the street needed sex instruction from his social betters. Nevertheless, it was decided that the time had come for a bloody example to be made.

The scapegoat was the gentleman Benjamin Deschauffors, who was burned alive in Paris for, among other things, selling boys to French and foreign aristocrats and running a “sodomy school.” More than two hundred people were implicated in the Deschauffors affair, including a bishop who was banished to his seminary and the painter Jean-Baptiste Nattier, who cut his own throat in the Bastille while awaiting trial. The majority of those accused received jail terms of a few months. Yet if the police hoped that a rare execution would deter others who were “infatuated with the crime against nature,” they were very wrong. Paris continued to host more than its share of homosexual action, especially in the Tuileries and Luxembourg Gardens, the city’s taverns, and the libertine wonderland that was the Palais-Royal. At least one-third of the men caught by police were married.

By 1750, only three additional men had been put to death for sodomy, two of whom had been caught in the act. If the lives of sodomites were relatively safe, though, their overall legal status remained precarious. The Deschauffors affair was enough to keep people on their toes, especially those with no money or connections. By the 1780s, a special Paris police division was conducting nocturnal “pederasty patrols.” Commissioner Pierre Foucault kept a list, in a big book, of tens of thousands of suspected sodomites—as many, he claimed, as there were female prostitutes in the city. The patrols’ nightly catches could be as mundane as hauling in a haberdasher for sticking his hand down the pants of a wig-maker during a public execution, or as colorful as an orgy bust in the Palais-Royal. They all went into the book.

By 1791, as the French Revolution raged and King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette languished in jail, the Constituent Assembly approved a new set of criminal laws that omitted any mention of sodomy and sins against nature. Thus a crime was erased on the books, but not in the minds of many of the people—including the police. The next century would see the heavy use of laws against public decency to harass those engaging in homosexual sex.

11

VIRGINS AND VD

Venereal diseases had everything to do with the way the law dealt with sex, especially sex for money and sex by force. Current thinking held that “good” girls didn’t pass on sexually transmitted diseases; only the “bad” ones did. Men were innocent victims. “[M]en contract this evil from women that are infected,” according to one medical source, “because in the [sex] act . . . the Womb being heated, vapors are raised from the malignant humors in the womb, which are suck’t in by the man’s Yard.” In this way, held another authority, “the Pocky Steams of the diseased woman do often evidently imprint their malignity on the genitals of the healthy play-fellows.”

The pain and embarrassment of venereal disease, especially syphilis, made people desperate for a solution. The dozens of “cures” available for purchase, such as mercury injections, were often as dangerous as the disease itself. Among the remedies, many agreed that one was superior: intercourse with a young virgin. In London and elsewhere, men sought to cleanse their “pocky” members in the pure fluids of prepubescent girls. Brothels profited by this “defloration mania” by touting purportedly untouched girls. The same girls were sold as virgins time and again, often with “patched up” maidenheads and little blood pellets strategically placed in their vaginas. However, customers with even a little common sense must have known they were not really getting what they paid for. Only truly innocent little girls would do, and to get at them force was usually involved. From 1730 to 1830, at least one-fifth of the capital rape cases in London’s Old Bailey involved young children. While the rapists’ motivations were not always clear, many were at least in part trying to cure themselves of sexual diseases. The courts never accepted this as a defense, but that did not stop people from believing it to be true.

Consider James Booty, who had raped five or six children less than seven years old by the time he himself turned fifteen. Shortly after being infected by his cousin, a friend told him that “a man may clear himself of that distemper by lying with a girl that is sound.” Booty went after every little girl within his reach, including his master’s five-year-old daughter. His master had the money and the motivation to push through a prosecution, and Booty was executed, but that result was not typical.

English law never gave much of a hoot about protecting small girls from sexual predators. The traditional age of consent for females was ten, well before the arrival of puberty for most—which allowed men to develop a taste for tender girls. Said one libertine in 1760: “The time of enjoying immature beauty seems to be the year ’ere the tender fair find on her the symptoms of maturity”—that is, before menstruation “stained her virgin shift,” and while “her bosom boasts only a general swell rather than distinct orbs.” This fetish for taking virgin children became widespread and was, at least tacitly, tolerated.

If a child rape case did make it into court, there was a four-in-five chance the assailant would be acquitted, because the law required proof that the sex had been forced, and that the man had ejaculated inside the victim. Practically, that meant that immediately after a child was raped she had to have the presence of mind to find someone reputable who would, in effect, violate her again to obtain critical evidence. Given that the victimized girls were usually brought down by terror, shame, and physical pain, the reality was that they were there for the taking. Even when there was proof of rape, the high cost of a trial effectively slammed the courthouse door in the victims’ faces. In one case, the nine-year-old daughter of a servant woman named Margaret East was raped and infected by a man East had trusted. When East could not pay the medical examiner’s fees, the examiner hired himself out to the rapist and testified that the girl’s hymen was still intact. The man was acquitted.

IN THE UNITED States, a man’s social position also protected him against a rape conviction. The 1789 diary of Martha Ballard, a rural Maine midwife, bears haunting witness: Ballard’s neighbor, Rebecca Foster, told her that several men had “abused” her since her husband Isaac, a pastor, had left the area on business. One of the abusers was Joseph North, a local power broker, who had broken into Foster’s house and treated her “wors [sic] than any other person in the world had.” Foster sought Ballard’s counsel. “I Begd her never to mentin it to any other person,” wrote Ballard. “I told her shee would Expose & perhaps ruin her self if shee did.” Foster rejected Martha’s advice and told her husband Isaac about the incident. The pastor then took the extraordinary—and risky—step of suing North for the rape.

The trial took place in the tiny river town of Pownalboro. The judges sailed upriver from Boston to the courthouse, as they did twice a year, with valises full of powdered white wigs and black robes. Ballard, who was called to testify, took a boat downriver to Pownalboro—her first visit there in twelve years. The drama was high. Rape cases were rare, and any woman who accused a powerful man of the crime could expect a withering counterattack. Ballard’s diary recorded “strong attempts” at trial “to throw aspersions on [Foster’s] Carectir.” Although it was not spelled out, there is little doubt that North’s lawyers would have accused Foster of entertaining men while her husband was away. The matter was further complicated by the fact that Foster had delivered a baby almost nine months after her encounter with North. Most likely, North’s “aspersions” of Foster included the charge that she was trying to force a wealthy man to support someone else’s child.

On July 12, 1789, North was acquitted, “to the great surprise of all that I heard speak of it,” according to Ballard. The Fosters and their children left the area for good and settled in Maryland until Isaac’s death in 1800. Rebecca then went to Peru with her youngest son to prospect for gold.

12

LOVING THE LASH

Samuel Self underestimated his wife Sarah when he sued her for divorce. The Norwich bookseller thought he had a good plan. He had trapped Sarah and her lover, John Atmere, in flagrante delicto, so the court would likely let him out of the marriage without having to pay her anything. Never, he thought, would she have the cheek to strike back by revealing the continuous group sex, erotic whippings, and impromptu sexual shows they had both been hosting in their house for several years. But she did—and by the time the legal proceedings were over Samuel and Sarah were both ruined.

The marriage had never been a healthy one. Samuel was still a virgin at their wedding in 1701, and within a few weeks Sarah had given him gonorrhea. Soon after that she was climbing uninvited into the bed of married neighbors, proposing ménages à trois and presenting a tuft of her maid’s pubic hair as a gift. Whether Samuel was aware of Sarah’s late-night wanderings isn’t known, but by 1706 his own sensibilities were no longer innocent. With the active assistance of Atmere, their maid, and some lodgers, the Self house had become a freewheeling swingers’ club, in which sexual partners were traded and whipped each other silly while the others watched.

The most common element of the orgies at the Self house was group flagellation, usually involving Samuel taking a lash to a lodger, Jane Morris. According to the court, Samuel had “indecently, immodestly, lewdly and incontinently” abused Morris “by turning up her clothes and whipping her bare arse, with rods . . . fit instruments for [his] awkward lewdness and devious incontinence.” Morris was often held down by others in the house while Samuel gave her a whipping. Each application of the lash brought Samuel to a new level of excitation, so much so that on several occasions he threw the lash down, grabbed his wife, and begged Atmere to whip her.

This was all confusing for the court, and delightful for Norwich’s gossipy townspeople. The proceedings dragged on for two years, each new sworn deposition adding a lurid splash of color to the picture. What was the court to do? Given the Selfs’ perversions—he an obsessed whipper, she an all-purpose party girl—how could the court judge one more worthy than the other? It was not easy, but judging is what courts must do. Despite the evidence that Samuel was an adulterer himself, the divorce was approved, and Samuel was not compelled to pay alimony, but after two years of court action Samuel’s reputation among the respectable folks of Norwich was ruined. His book business fell apart, and in 1710 he was arrested for passing bad financial paper. As for Sarah, she was left homeless and broke.

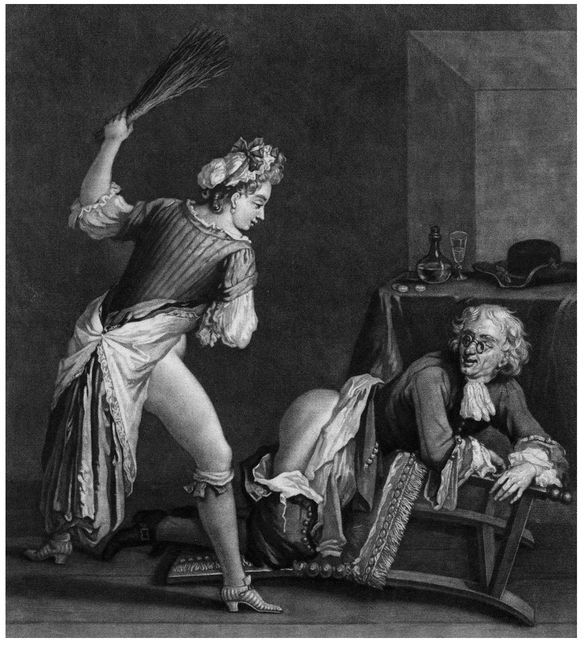

The Selfs’ penchant for whipping was “gross and unnatural” to the court, but it was not atypical. Flogging, both as punishment and as sex play, was common, and most courts were reluctant to penalize it. In 1782, one judge ruled that a man may beat his wife without legal consequence so long as the stick was no thicker than the width of his thumb. The court was referring to discipline, but the line between punishment and prurience is not always clear. Jean-Jacques Rousseau spoke for many of his contemporaries when he wrote, in his Confessions, that he grew to love whippings as a child: “I found in the pain, even in the disgrace, a mixture of sensuality which had left me less afraid than desirous of experiencing it again.” For the rest of his days, Rousseau wanted to be whipped.

Whipping skills were part of any good prostitute’s repertoire. The newspapers were filled with advertisements for brothels offering a good flog. William Hogarth’s famous 1732 series of engravings, A Harlot’s Progress, depicts, among other scenes, a prostitute in her boudoir with a collection of birch rods close at hand. One madam later employed a specially crafted flogging machine onto which she strapped her customers, while another machine administered whippings in industrial volume by accommodating forty men at once.

THE PLEASURES OF THE BIRCH

The British loved their flogging. Whipping skills were part of any good prostitute’s repertoire and domestic violence was generally tolerated by the courts, unless it reached “gross and unnatural” proportions. ©THE TRUSTEES OF THE BRITISH MUSEUM

The Selfs’ divorce trial roughly coincided with a burst of new pornography devoted to the pleasures of the birch. To choose just two examples, the reprobate publisher and bookseller Edmund Curll did well with the quasi-scientific

Treatise on the Use of Flogging, while John Cleland’s monumental erotic novel

Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (Fanny Hill) devoted much space to the practice. Cleland describes, in loving detail, the prostitute Fanny Hill’s harsh treatment of a man she ties to a bench with his own garters. Once she has reduced his “white, smooth, polish’d” buttocks to a “confused cut-work of weals, livid flesh, gashes and gore,” Fanny offers up the “trembling masses” of her own “back parts” to the man’s “mercy.” At first he uses the rod gently, but after a few minutes, “He twigg’d me so smartly as to fetch blood in more than one lash: at sight of which he flung down the rod, flew to me, kissed away the starting drops, and, sucking the wounds, eased away a good deal of pain.” Miss Hill finds the experience to be disconcerting at first, but after a glass of wine the “prickly heat” of her wounds puts her into a state of “furious, restless” desire for traditional sex. Her partner gladly obliges.

13

BEASTS BURDENED

Intimate relations between people and animals (especially goats) were, as we have seen, traditionally condemned as sodomy and associated with devil worship. As the animals involved were considered evil in themselves, they were executed too, often before their human partners’ eyes. With the abatement of the witchcraft craze at the end of the seventeenth century, however, a more lenient view toward bestiality emerged. Centuries of cruel punishment had done nothing to dissuade people, especially farmers, from loving their animals. City dwellers had fewer opportunities for such sex, but they nevertheless showed their interest by fuelling the market for bestial pornography. Somewhere along the line, sex with animals became less radioactive. It was seen as just one category of sex crime among many others.

When, in 1642, young William Hackett was caught in Massachusetts inserting his member in a cow, he told the court that such things were perfectly normal back home in rural England. This defense did not save Hackett from punishment—or the cow, for that matter, who was burned before Hackett’s eyes—but it did show a certain nonchalance about the subject that could not have been his alone. When the Prussian king Frederick the Great was told that one of his knights had sodomized a mare, the monarch’s reaction was more bemused than horrified: “That fellow is a pig; he must be placed in the infantry.”

Animal abusers were still burned at the stake, but less frequently than before. Some courts even started to judge the animals on their own merits. In a 1750 French case, Jacques Ferron was caught making love to a female ass. Ferron was sentenced to death, and while the ass would normally have been condemned as well, this one was acquitted on the grounds that she had been a victim of violence and had unwillingly submitted to Ferron’s desires. The court was influenced by a group of religious and civil officials who had signed a petition stating that the ass “is in word and deed and in all her habits of life a most honest creature.”

By the close of the seventeenth century, most penalties against human beings for using animals sexually had been reduced, by formal changes either in the law or in practice. Shorter jail terms replaced life imprisonment and execution. In 1791, an English tailor who took liberties with a cow was imprisoned for only two years. The French civil code after the Revolution ignored the subject completely, as did the laws of other countries that fell under French influence. By 1813, the offense would be decriminalized even in such conservative Catholic states as Bavaria.

At the same time, anyone caught in a compromising position with an animal could still count on his or her reputation being destroyed, especially if the offender lived in a city. Rather than take chances, many animal aficionados satisfied their desires with pornography. In 1710, Edmund Curll published a report of a seventy-year-old trial he titled The Case of John Atherton, Bishop of Waterford in Ireland, Who Was Convicted for the Sin of Uncleanliness with a Cow and Other Creatures, for Which He Was Hang’d at Dublin. Curll charged a shilling for the four-page pamphlet—an admittedly “very high” price, but one he was confident “would not fail of alluring buyers at any rate.” Pornographers also discovered that men enjoyed fantasizing about women and beasts together, especially with household cats and dogs. Whether women ever did the things described in the books is anyone’s guess, but there was no shortage of men who liked to think about it.

Tender intimacies with pets held no interest for the Marquis de Sade, whose treatment of animals in his books was nothing less than horrifying. In

The 120 Days of Sodom, for example, he describes a libertine with a special passion for turkeys. At one point, the man puts his penis in a bird whose neck is held between the thighs of a girl lying facedown. At the same time, another man joins the scene to bugger the man violating the turkey. As the pleasure builds to a climax, the turkey lover cuts the bird’s throat. Sade was not personally prosecuted for this scene or, for that matter, the book’s passages involving baby rape, torture, and bloodsucking. He was already imprisoned in the Bastille when he composed the work, and never intended for it to be published. It would not be until the 1960s that his works would be published without censorship, by which time intellectuals, such as Geoffrey Gorer, had already hailed him as a revolutionary genius and

Sodom as “one of the finest works of morals one could hope for.”

14

DIRTY BOOKS AND SPILLED SEED

It was during the French Revolution that the French word pornographie assumed its modern definition as a category of “immoral” sex books, but outside the courtroom no one needed a formal explanation. People knew what pornography was when they saw it, and they saw it everywhere. By the end of the century the publication of sexually explicit materials began to resemble the sprawling industry it is today, catering to all tastes and using all available media. Governments tried to repress it, but those efforts usually failed. Many French pornographers charged large sums for not publishing sexual attacks on royals and aristocrats. Never before or since has sexual material packed the political and social wallop it wielded in the eighteenth century. Pornography weakened the French ruling class, especially its kings and queens. It also normalized sex outside the marriage bed and guided the masses out of centuries-old Christian taboos. More than anything, it made some people a lot of money.

Sexually titillating material lurked in unlikely places. While Tissot’s L’Onanisme denounced pornography’s prime objective, masturbation, in the harshest terms—the good doctor said it made people insane, idiotic, hemorrhoidal, impotent, and short-lived—a substantial percentage of his readers used the book itself as an aid to masturbation. In 1835, the American clergyman John Todd published a key passage of his guide to moral behavior, The Student’s Manual, in Latin, in order not to excite the minds of the very young. The passage warns against the “frequency and constancy” of “the practice of pouring out by hand.” Todd also instructs his readers to talk sternly to their hands when they become tempted to touch themselves. (The young men were to say: “Hand—stay your lasciviousness!”) The use of Latin probably made the book that much more titillating, if not amusing, to his readers, and surely contributed to the book’s success: It ran to at least twenty-four editions and sold one hundred thousand copies in Europe. No less useful as masturbation aids were sex and marriage guidebooks such as Aristotle’s Masterpiece and Venette’s Secrets of Conjugal Love. One young man named John Cannon wrote in his memoirs that he regularly masturbated to a midwifery manual until his mother took it away.

The popular press was a major source of pornography, with many of its “reports” concerning divorce and adultery trials. Anyone interested in, say, an illustrated account of a duke’s impotence or his wife’s infidelity had a variety of choices. There were “sessions papers,” reports of sex trials at London’s Old Bailey, for example, or the writings of a prison chaplain who took the confessions of sex criminals, collected as The Ordinary of Newgate, His Account of the Behaviour, Confession, and Dying Words of the Malefactors Who Were Executed at Tyburn. Yet these publications were often outdone by newspapers and the hacks of Grub Street, a London lane that housed low-end booksellers and impoverished writers. (“Grub Street” soon became synonymous with the disreputable end of the publishing industry.) On Grub Street, printers stole others’ material, embellished trial reports with spicy details, and slapped misleading, sexy titles on their products. It was all fair game.

The dean of Grub Street and the father of the modern English pornography publishing business was the aforementioned Edmund Curll. Tall, ungainly, goggle-eyed, and described by Thomas Amory, one of his contemporaries, as a “debauchee to the last degree,” Curll noticed that the buying public was more interested in sex than in just about anything else. He also found new, creative ways to take his customers’ money. One of his early successes was a 1708 book, The Charitable Surgeon, which celebrated a new cure for “venereal distemper.” The concoction the book promoted, as well as the equipment for administering it, was on sale at Curll’s bookshop.

In 1714, Curll found a gold mine: a two-volume edition of “reports” about a French trial in which an aristocratic wife sought divorce on the grounds of her husband’s persistent impotence. The books were larded with detailed “physician’s accounts” and special sections on virginity, “artificial maidenheads,” and “Examples of some remarkable Cases of natural Impotence.” Curll built on this success with a collection of English trial reports about impotence and perversion, including a reprint of court materials about the notorious seventeenth-century bugger and rapist, the second Earl of Castlehaven (see Chapter Five). Curll’s success was well noted by his contemporaries, and before long there was no end of books and pamphlets covering polygamy, adultery, and rape cases. One account told of the 1729 rape trial of Colonel Francis Charteris, who was charged with raping his servant, Ann Bond. The cross-examination of Bond was reprinted in full:

Being asked whether the Prisoner [Charteris] had his clothes on? She [Bond] reply’d, he was in his night gown. Being asked whether she had not her petticoats on? She reply’d yes; but he took them up, and held her down on the couch. Being asked, whether she was sure, and how she knew he had carnal knowledge of her? She reply’d, she was sure she had, and that he laid himself down upon her, and entered her body. She was asked how it was afterwards? She reply’d that there was a great deal of wet . . .

By the 1770s, the genre had reached full flower, especially in its use of pictures. A luridly illustrated set of volumes called

Trials for Adultery: Or, the History of Divorces. Being Select Trials at Doctors Commons, for Adultery, Fornication, Cruelty, Impotence, etc. promised on its cover to provide a “complete history of the Private Life, Intrigues, and Amours of the many Characters in the most elevated sphere: every Scene and Transaction, however ridiculous, whimsical, or extraordinary, being fairly represented, as becomes the faithful historian, who is fully determined not to sacrifice the Truth at the Shrine of Guilt and Folly.”

15The next decade saw dozens more of such accounts, one of the most widely distributed being of Sir Richard Worseley’s £20,000 suit against one of his wife’s lovers, George M. Bisset. Worseley technically won the case, but the jury had no love for him—he was awarded just one shilling. The evidence showed that he had enjoyed showing off his wife to friends when she was undressed. On one occasion, while she was taking a bath, Worseley raised Bisset on his shoulders to let him take a peek at her through a crack in the wall. “On coming out . . . [the wife] joined the Gentlemen; and they all went off together in a hearty laugh.” The popular accounts of this scene were, of course, graphically illustrated.

Curll not only helped create a new platform for pornography, he was also the key player in the lawsuit that set England’s legal standard for obscenity—a precedent that lasted until 1959. His trial reports were mostly safe from legal challenge because they focused on the foibles of real people in real courts, but that was not all he produced. He also put out the Treatise on the Use of Flogging; tracts dealing with masturbation, hermaphroditism, and sodomy; and collections of sexy poems such as The Peer and the Maidenhead. In 1724, he released an English translation of the French book Venus in the Cloister, or the Nun in Her Smock, which purported to describe certain “goings on” in French convents. The book went into two editions before Curll was taken into custody and brought to court on a charge of publishing “lewd and infamous books.”

The trial concerned both Venus in the Cloister and the flogging treatise, but it was the former that most concerned the court. With its descriptions of bed-hopping, masturbating, bisexual nuns, this book was as lewd as any Curll had published. To his advantage, English law at the time had no clear standard for determining which kinds of books were too bawdy to sell. In fact, what law did exist on the subject seemed to favor Curll. In a 1708 case concerning the book The Fifteen Plagues of a Maidenhead, a court ruled that obscenity cases should be dealt with by the church courts, as no secular law forbade material of a sexual nature, even if it “tends to the corruption of good manners.” If the courts had refused to punish Maidenhead, argued Curll’s lawyer, they should let Curll off as well.

The government’s attorney disagreed, arguing that Curll’s book corrupted the morals of the king’s subjects and disturbed the peace. If the courts had any interest in guarding the realm’s good order and general morality, he told the court, it was their obligation to take the situation in hand. Meanwhile, Curll did everything he could to exacerbate the situation. While he was out on bail, as the court was trying to figure out what course to take, he published The Case of Seduction . . . The Late Proceedings at Paris against the Rev. Abbé des Rues for Committing Rapes upon 133 Virgins, and also put out the memoirs of a notorious spy. After these works appeared, he lost his case. The court agreed with the government’s attorney that if a book “tends to disturb the civil order of society ... it is a temporal offense.” Interestingly, in its ruling the court was influenced by an earlier case (discussed in Chapter Five) concerning Sir Charles Sedley, who was fined for disturbing public order after he defecated out the window of a tavern. Sedley had soiled the realm with excrement; Curll was staining England with words about oversexed French nuns.

Curll was ordered to pay a small fine and stand in the pillory for one hour. Depending on the public’s opinion of an offender, even such a short stand in a pillory could be a terrible ordeal. Sodomites were pelted with filth and dead cats. Mother Clap, the notorious molly house keeper, nearly died there. Ann Morrow, who was found guilty of marrying three women while impersonating a man, was blinded in both eyes by objects flung at her by spectators. Yet Curll had thought ahead, and made sure he would suffer no such indignities. According to one contemporary report:

This Edmund Curll stood in the pillory at Charing Cross, but was not pelted nor used ill; for being an artful, cunning (though wicked) fellow, he had contrived to have printed papers dispersed all about Charing Cross, telling the people that he stood there for vindicating the memory of Queen Anne; which had such an effect on the mob, that it would have been dangerous even to have spoken against him; and when he was taken down out of the pillory, the mob carried him off, as it were in triumph, to a neighboring tavern.16

Curll died in 1747, just before a no-account writer and civil servant named John Cleland was sent to jail. Cleland, future reteller of the Catherine Vizzani story and author of Fanny Hill, had returned to England several years earlier from a failed career with the British East India Company and had found no success at home. His debts multiplied, leading to his arrest and a one-year stretch in debtor’s prison. While incarcerated, the bookseller Ralph Griffiths offered him a small sum to write some drivel about a fictional London prostitute. The work—Fanny Hill—was published with huge success while Cleland was still behind bars and became the key event in the history of English-language pornography and a flashpoint in Anglo-American obscenity law for more than two centuries. It was not until 1966 that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the book was protected from censorship. England first permitted the entire book to be sold in unabridged form in 1970.

Reading through Fanny Hill, it is hard to see what all the fuss was about. There is not one obscene word in the work, the sex is mostly conventional, and the story resolutely middle-class. Fanny is a young girl from the hinterland who comes to London as an orphan and ends up in a brothel. There she loses her virginity to Charles, with whom she falls in love but to whom she must bid goodbye when he is sent to the South Pacific. In his absence, she achieves success in the business of pleasure, eventually opening her own establishment and inheriting the fortune of one of her clients. Finally, Charles returns, they marry, and Fanny lives out her life “in the bosom of virtue.” The book ends on a suitable tone, with Fanny telling her readers that the sensations of vice are “spurious,” “low of taste,” and “inferior” to the joys of a moral life: “If I have deck’d [vice] with flowers, it has been solely in order to make the worthier, the solemner sacrifice of it, to Virtue.”

Pretty mild stuff, but after the Curll case the publisher took no chances. Griffiths had kept his name off the book, while Cleland was represented only as a “person of quality.” Neither measure fooled the authorities for long. In 1749 a warrant was issued to seize the author, printer, and publisher. Cleland had none of Curll’s courage. He told the court he regretted writing Fanny Hill, and that he had only done so to escape poverty. The indignities he had already suffered were, he claimed, punishment enough: He was “condemned to seek relief . . . from becoming the author of a Book I disdain to defend, and wish, from my soul, buried and forgot.” Cleland’s groveling worked, and he was given a hundred-pound annual pension in exchange for his agreement to stop writing pornography. For Griffiths’s small investment, he had made about ten thousand pounds.

From that point forward, unexpurgated versions of Fanny Hill went underground and multiplied. Repeatedly abridged, translated, illustrated, and confiscated, no work of pornography has ever been as popular. It was a favorite of soldiers and snobs, a barracks-room staple during the American Civil War, and even a token of international goodwill: The future Duke of Wellington took along eight copies on an extended voyage to India, presumably both for his own shipboard pleasure and to give as gifts. In 1819–20, Fanny Hill was the subject of the United States’ first prosecutions for the sale of obscene literature, when two traveling booksellers were fined and imprisoned for trying to sell the novel to Massachusetts farmers. By 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court would be sharply divided over the question of whether or not the book should be sold. Long after much more explicit material had survived obscenity charges, Fanny Hill was still too much for three of the nine justices to stomach. “Though I am not known to be a purist or a shrinking violet,” wrote Justice Tom C. Clark in his dissent, “this book is too much even for me.” Despite Clark’s qualms, the Court’s majority ruled that the book had some merit, and therefore could not be banned.

After the Fanny Hill decision, a book could claim protection under the First Amendment if it had an iota of “redeeming social value,” even as a curiosity. The Fanny Hill case was all the more critical because it concerned such a substandard piece of writing. Other works that had squeaked through the courts over the years, such as Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer and James Joyce’s Ulysses, were ambitious works of literature. Fanny Hill, by contrast, was “nothing but a series of minutely and vividly described sexual episodes.” If it had social value, then social value was very easy to find.

No one would have been more surprised by the

Fanny Hill decision than John Cleland himself. When he wrote the book in a stinking jail, he never could have imagined that its artistic merits would be seriously scrutinized by the most august court in the English-speaking world. Based on Cleland’s later disavowal of the book, he would have been the first to agree with Justice Clark that it was “bankrupt” in “both purpose and content.”

17

AS PROBLEMATIC AS Fanny Hill has been over the years, it is completely apolitical. Nowhere does Fanny or any other character show any interests beyond their next erotic adventure, which well suited the tastes of Cleland’s readership. English pornography was a private affair; the middle and lower classes could enjoy reading about the sexual foibles of the aristocracy, and books about fantasy prostitutes such as Fanny Hill were appealing to all, but no harm was done. No one really believed that the state was ever put at risk by a sexy book.

Not so in France, where pornographic attacks on the upper crust were weapons of rebellion. The tradition of printing pamphlets about the real or imagined debauches of the powerful, called