TRIPLE PARLAY CRAPS OUT IN VEGAS

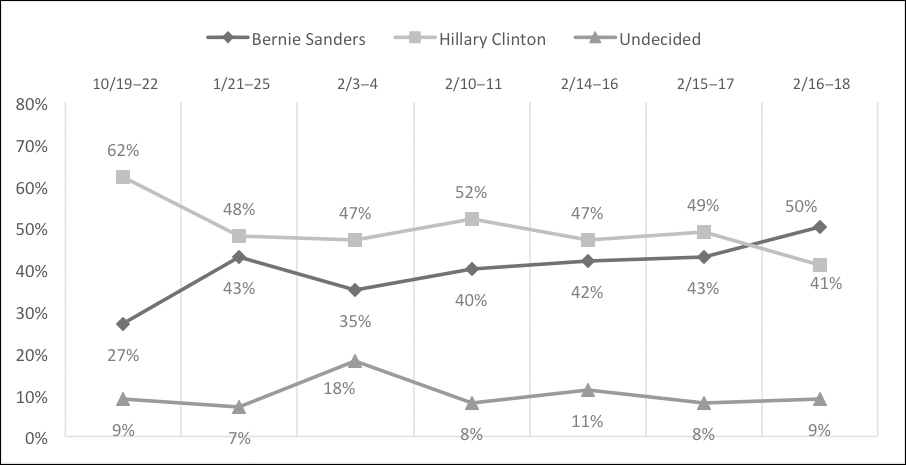

FOLLOWING OUR BIG WIN in New Hampshire and come-from-behind tie in Iowa, our tracking polls showed Nevada closing to a dead heat. That was a tremendous improvement from our 33-point deficit in October and what was still a 15-point deficit in the third week of January. Tad’s four-state knockout theory suddenly seemed not so crazy, even though we remained way behind in South Carolina. We acted immediately to take advantage of our newfound momentum.

We upped our TV buy there. And I authorized every single organizer from New Hampshire to go immediately to Nevada. But a number of critical factors conspired—both literally and figuratively—against us in the Silver State. The first was that our opponents also realized their deteriorating situation. They had talked for months about their racial firewall in Nevada and South Carolina. If we could breach it, they would be in real trouble. They also understood that, and started downplaying the importance of Nevada to their firewall, calling it an “80 percent white state,” a move that created pushback from both then senator Harry Reid and the Nevada Democratic Party.

The entire Clinton family was dispatched to Nevada to fight for a comeback there. Campaign manager Robby Mook had run Nevada for the Clintons back in 2007–8, so he was familiar with the state. They knew it inside and out in a way we did not, and they were going all-in.

Priorities USA, Clinton’s super PAC, joined the fray. From the New Hampshire primary through the Michigan primary (a little over a month later), Priorities spent $4.2 million on direct mail and radio ads to support Hillary Clinton, as reported by Time’s Sam Frizell. The same article notes that Priorities intended to spend another $4.5 million on top of that in the March states that followed Michigan.

Our own organization in Nevada had had fits and starts from its very beginning. In the early fall, we hired Jim Farrell to be the state director. Jim was living in New Mexico and had worked with late senator Paul Wellstone when I was with Bernie in the House. We spoke by phone about the position, and he was extremely enthusiastic about it. He quickly moved to Nevada.

Jim began adding staff, but even early on we had problems—caused, in large part, by an internal power struggle in the state. Without laying the responsibility at anyone’s feet, I would say that it created a toxicity in the organization that would have an impact until the caucus. As it came to a head in early November, Phil and I had conversations with Jim. We were going to be in Nevada in the next forty-eight hours for a rally in Las Vegas, so I suggested we put off trying to resolve the issue until we were on the ground and could meet in person.

Unfortunately, Jim decided to leave the campaign. On November 8, while we were in the air to Las Vegas, he packed up and left. Our arrival in Nevada was met with questions from the local media about our state director resigning when the Clinton campaign had such an early lead on us in terms of organizing. What we did not need was a negative narrative about our insurgent campaign coming apart in Nevada.

These stories practically write themselves. They have a timeline, identifiable personalities, and real or imagined drama. The truth is that the impact on a campaign the size of a presidential run (whether ours or anyone else’s) of this or that person joining or leaving is almost always far less than is imagined.

Regardless, it was a political issue, if not a practical one, that had to be resolved quickly. Phil and I met with several staffers in the opulent lobby of the Mandalay Bay hotel. It was clear that there were two camps. Each had a candidate for Jim’s replacement. Picking someone from one of the camps to succeed Jim Farrell would have created even more problems than we already had.

Phil and I sat privately after our meetings. We settled on Joan Kato as Jim Farrell’s replacement. Joan had some Obama-related experience in Nevada. She was also extremely confident. In our interview that day, I asked her if she would accept the state director position if offered. She didn’t skip a beat. “Yes,” she said. We announced it to the staff. One of the other candidates for the position decided to leave Nevada. The other stayed on as field director. It turned out later that everyone would have been better off if he had been the one to leave.

Later in the campaign, he tried to lead a coup in Nevada against Joan Kato. He organized a letter from senior staff with a list of grievances against her. I don’t like coups. They have no place on campaigns. If you have a problem or you believe the campaign has a problem, give me or someone else a call. That is everyone’s responsibility on a campaign. But coups? Nope.

With the help of national field director Rich Pelletier and John Robinson, we fired the pretender to the throne. A deeper middle-level management structure would have allowed us to deal with some of the concerns in a more nuanced way. But we did not have the staffing or time. We had to push forward.

By the time we left Nevada, the Las Vegas Sun was reporting that after Jim’s departure “campaign staffers were in disbelief. But by the start of the rally they already had a replacement, Joan Kato, and shooed off any notions that the campaign would suffer.” We had turned a narrative of the campaign falling apart in Nevada to one of a smooth, professional operation that dealt quickly and decisively with bumps in the road. Immediate problem solved. Nevada, though, would continue to face challenges, internal and external.

Everywhere we went across the country, individuals were extremely kind to our campaign. And there was no place where that was more true than in Nevada. But that was not the case with the Nevada Democratic Party or some of the other insiders. The Nevada Democratic Party proved to be adversarial—a problem that worsened over time, until much-publicized confrontations between Bernie supporters and party officials occurred at both the Clark County Democratic convention and the state convention.

Joan Kato discovered, while traveling around the state, that Hillary Clinton’s local campaign headquarters were in some cases co-located with the Democratic Party headquarters. This was clearly unacceptable. Our complaints to the party at first were ignored. Then the state party claimed that they had no control over local parties. Finally, after weeks of badgering, we got some movement in terms of separating offices.

Beyond that, the Nevada Democratic Party had real competency problems. For example, they had lost tens of thousands of records from the 2008 caucuses. This made it extremely difficult to contact voters who were previous caucusgoers.

In fairness, there were occasions when we unnecessarily rubbed them the wrong way. At the annual Nevada Democratic dinner, our people brought obnoxiously loud air horns and vuvuzelas. The noise was cacophonous. It made it difficult if not impossible to hear the speeches. Even when Bernie spoke, the revelers would break into “music,” as he described it, every time he got to an applause line. As a result, the crowd could not hear him. I have since heard that such noisemakers are now prohibited. At the time, they were a sign of the growing frustration our people on the ground felt toward the conduct of the party establishment.

Speaking of the party establishment, Harry Reid publicly stayed neutral during the caucus process. He and Bernie had a long history together in the Senate, and Senator Reid had always been fair to Bernie. He also indisputably controlled the Democratic Party in Nevada. He was its patron, its protector, and its master. So having Senator Harry Reid be neutral was a big benefit to us.

Jon Ralston would later write, in USA Today, that Harry Reid had in fact intervened with both the biggest union in the state (also officially neutral) and casino owners to help ensure a Clinton victory. Describing Reid as a “man with one eye” and someone “Machiavelli would have bowed to,” Ralston claimed that a major part of Reid’s effort was to convince the casino owners and the casino workers’ union to pump turnout at the caucus locations on the Strip.

Unique to Nevada, some caucus sites are located in the casinos. The well-intentioned purpose of these sites is to allow Nevada shift workers who wouldn’t be able to make it home to participate in the caucus. However, establishing caucus locations that are essentially controlled by large employers has problems, and that system needs to be carefully scrutinized before the next cycle. I have heard more than one Obama supporter/worker complain that they were physically barred from entering caucus sites at pro-Clinton casinos in 2008.

That being said, the problem with Ralston’s claim is that increasing the number of participants alone in these locations would not have benefited Clinton, because the number of county convention delegates allocated to each site was set prior to the caucus. The only way to ensure victory is to change the proportion of the people in the room who support each candidate. In other words, you would have to pack the room with Clinton supporters. Did that happen? Online video did circulate that shows people streaming into at least one casino caucus location without checking in, so it is certainly possible that there were shenanigans. But that is not Ralston’s claim. In the end, it is difficult to know how accurate Ralston’s narrative is.

Jon Ralston is a journalist/talking head held out as a local expert on state politics—your go-to insider. Most states have one. Unlike most, Ralston’s view is, shall we say, more “truthy” than truthful. In fact, he was the source of all the false reporting about chairs being thrown at the May 14, 2016, Nevada state Democratic convention. Even though he had long left the event, he tweeted that chairs had been thrown by Bernie supporters. There was no evidence to back him up. No video. Nothing. In terms of fake news in the 2016 campaign season, Ralston was the king. (In 2014, he had been exposed by Watchdog.org after continually attacking the Nevada Republican attorney general candidate without disclosing that he was actively working to help elect the Democratic candidate.)

No evidence of chair-throwing could be produced because it never happened. A top Clinton representative who was there the entire time was greatly amused when I asked him about chair-throwing at the Nevada state convention when we were together at the Orlando Democratic platform committee meeting. “Was there a single chair thrown?” I asked him. Holding back laughter, he said, “No.”

The national news media ran with Ralston’s fake story—Alan Rappeport of the New York Times, Erica Werner of the Associated Press, Rachel Maddow of MSNBC, NPR, and more. Later, in a May 18 determination, NPR’s own ombudsman, Elizabeth Jensen, found NPR’s story lead—which included reference to violence and chair-throwing—“misleading.”

Never one to miss a chance to pile on, Debbie Wasserman Schultz went on CNN to attack Bernie. In an interview with Chris Cuomo, I subsequently called her out for “throwing shade on the Sanders campaign from the very beginning”—a line that played all day long on CNN.

CounterPunch’s Doug Johnson Hatlem reported that Jon Ralston later admitted to not having seen any chairs thrown (because he of course wasn’t there at the time, and no chairs were thrown). Rather, he had been relying on a local reporter, Andrew Davey. In this Twitter exchange, Davey vouches for the false chair-throwing story:

Jon Ralston @RalstonReports

Convention ended w/security shutting it down, Bernie folks rushed stage, yelling obscenities, throwing chairs. Unity Now! On to Philly 2/2

Andrew Davey @atdleft

Replying to @RalstonReports

Yep. We’ll have a full report tomorrow. People had to be directed out of the room when the chair throwing began.

Jon Ralston @RalstonReports

You get video?

Andrew Davey @atdleft

I have plenty of stills, & I’ve seen some videos posted around social media.—at Paris Hotel & Casino Parking Garage

Davey, whose Twitter profile describes him as a “troublemaker” and “Managing Editor at Nevada Forward,” proved that making trouble is a more important part of his résumé than journalist. He never produced any real proof.

What did happen was that a lot of our people showed up at the state convention expecting to be cheated. And with good cause. As Megan Messerly, then of the Las Vegas Sun, reported at the Clark County convention, only a few weeks before, party officials, at the express request of Hillary for America’s head lawyer, Marc Elias, had unsuccessfully tried to depose their own credentials chair, Christine Kramar, at what was supposed to be a secret meeting. Our people got wind of it and showed up, which scuttled the plan. The next morning, party officials announced that the credentials chair had been suspended for the day.

When the credentials chair wouldn’t leave the convention, the party called the police and threatened to have her arrested. Her crime: not being sufficiently reliable from the standpoint of the Clinton campaign. Elias’s letter contained only vague allegations of bias as justification for Kramar’s removal.

In hindsight, based on their challenge of the credentials of all delegates at the Polk County convention in Iowa, it is clear that manipulating the credentials process was a Clinton campaign strategy employed when they believed our delegates would outnumber theirs at party conventions. To pull that off, neutral credentials officials were not going to do. As in Polk County, our delegates at the Clark County convention outnumbered the Clinton delegates, even though more Clinton delegates were elected at the precinct level.

Matt Berg and Joan Kato were onsite and called me. They were discussing the incident with a representative of the party. I said to Matt Berg, “Please hand the phone over to him so I can talk to him myself.” I could hear Matt telling him that I wanted to talk to him. Matt came back on the line, “He won’t talk to you.” So much for trying to work things out.

We took to social media to try to put some pressure on the party to handle the process fairly. As reported by the Washington Post’s John Wagner, “Weaver also complained about the messy process, saying on Twitter that the Democratic National Committee should take a hard look at whether Nevada deserves one of the first four slots on the nominating calendar.”

I knew this was a pressure point for them. Because of Harry Reid’s position, Nevada was third. It was prestigious to be in the first four. It was justified as a means to ensure that the nation’s growing Latino population had a say early in the nominating contests. But that position didn’t have to be filled by Nevada. Colorado or New Mexico were other possibilities. My point about Nevada’s place in the calendar didn’t get any results in terms of a fairer process that day, but it didn’t go unnoticed.

I caught up to Bernie, who was preparing for a Wisconsin rally not long afterward. He wanted to see me right away. That didn’t sound good.

I walked into a small room and greeted him. “Hello, Bernie, how are things?” I asked. “Well, not good, Jeff. I just got off the phone with Harry Reid,” he said. His voice had a mischievous quality, indicating to me that there was more to come.

“Is that right?” I replied. I had a pretty good sense of what was coming.

“Yes, and guess what? Your name came up,” he continued. I definitely knew what was coming now.

“Did you say that you thought that Nevada shouldn’t be in third place?”

“As a matter of fact, I did,” I replied.

“Don’t you think you should have run something as important as that by me before you did it?” he said more seriously. Before I could answer, he continued, “Harry Reid is not a happy camper.”

“Well, there wasn’t a lot of time, Bernie. They were trying to rig the Clark County convention. We couldn’t let them steal this election, and I needed a pressure point,” I explained. “And it looks like I hit the right one if Harry Reid is calling you.”

“Alright, I get it,” he said. Then, almost as an afterthought because his attention was already returning to the upcoming rally, he added, “But next time you go after Nevada’s place, let me know ahead of time.”

“No problem, Bernie,” I said, leaving him to review his remarks.

Bernie and the whole campaign had evolved since the early days. We were all ready to go on offense to protect our supporters. Harry Reid wasn’t happy with me that day, but we were fine friends when we got to the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia.

These contentious and controversial convention issues, however, were far in the future when we arrived in Nevada for our final push following Bernie’s New Hampshire victory. With our polling now even, and with the cavalry in the form of dozens of New Hampshire field organizers on the way, we were in a very hopeful place.

Unfortunately, just as we were trying to ride the wave of momentum in Nevada and would have to effectively integrate all the new arrivals into a state organization that had its problems, I became quite ill. I spent days lying in my hotel bed fighting the fever, chills, and associated unpleasantness of the flu. I would sleep for two hours, then roll over to answer texts and emails before falling back to sleep. It was miserable.

I considered going home for a few days. But the thought of getting on a cross-country flight in my condition didn’t make sense. I struggled through it in Las Vegas. Now I find Las Vegas to be a fun place, but I can tell you that it is a lonely place to be sick in bed.

As caucus day approached, we were still hopeful despite our polling having slipped by 6 points. The turnout was the wild card. You can be down single digits and make it up by having an enthusiastic base of support that comes out for you. One bright spot was Bernie’s rapidly growing support in the Latino community. Among younger Latino voters in particular, that growth was explosive. From our first poll in October to late January tracking polls, Bernie’s relative support among Latinos aged eighteen to fifty-four shifted a full 60 percentage points. In our January tracking poll, we had pulled ahead of Clinton with this group of voters even though we continued to trail with white voters. In Nevada, as everywhere else, we were winning overwhelmingly with millennials.

It was not surprising to us that support among Latino voters was growing. Bernie often spoke of his father’s own immigrant story. And while every community’s immigrant experience is different, it resonated that his father came to the United States, speaking almost no English and with almost no money, in search of a better life for himself and his future family. In addition, our campaign invested heavily in reaching out to the Latino community—as we did with the African American community, although it took longer for support to build with black voters. The effort was spearheaded by Erika Andiola, Cesar Vargas, and the rest of our Latino outreach team.

Tulchin’s final tracking before the Nevada caucus, comprised of about 1,000 interviews, showed us up 9 points with Latino voters. The big driver of this win was a 14-point lead among Latinos aged eighteen to fifty-four.

On February 20, caucus day in Nevada, Bernie visited various caucus sites. As on every election day, we were scrambling for whatever intelligence was available. Tad and I were sitting in the backseat of a car when Tad called a friend at one of the media decision desks. A decision desk at a media organization is staffed by people who closely monitor voting patterns and election results on election day and make the judgment about when to call a race for this or that candidate. They look at all kinds of data, including turnout in various areas, and entrance and exit polls. It is their job to not make a mistake and embarrass their organization by calling a race wrong.

I remember driving down an interstate off-ramp in Las Vegas as Tad hung up his cell phone. He had been speaking with one of his decision desk contacts. It was early afternoon; the Nevada caucus had been going on for a couple of hours. As he hung up, Bernie asked, “So, what did they have to say?”

“Good news,” said Tad. “Based on what they are seeing now, they think you are going to win.”

The prediction was not confined to that one media organization. There was a growing expectation that Nevada could be as close as Iowa, or that Bernie could win outright. That expectations game would hurt us when the final results (a 5.3-point loss) came in, almost perfectly matching our late polling, which showed a 6-point deficit.

Both the Edison entrance and exit polls on caucus day confirmed another aspect of our polling. It showed us winning with Latinos by 8 to 9 points. Exit and entrance polls are media-funded interviews of actual voters at key voting locations. We put out a statement that we had won the Latino vote in Nevada, even though we lost the overall contest.

The Clinton campaign shot back. This reality went to the heart of their false narrative that Bernie had no support from voters of color. As reported by Politico’s Eliza Collins, the response of Clinton’s traveling press secretary, Nick Merrill, to our claim was to tweet: “I don’t typically like to swear on Twitter, but by all accounts so far this is complete and utter bull______t.” The New York Times’ Nate Cohn and FiveThirtyEight’s Nate Silver challenged our claim as well. Cohn’s piece cites the work of Latino Decisions—a firm that was retained by the Clinton campaign. If the Clinton campaign had any polling showing that it was winning Latino voters in Nevada, it never released them.

Here’s ours (never before released):

NEVADA 2016 PRESIDENTIAL CAUCUS VOTE OVER TIME AMONG LATINOS

What was needed was an independent expert validator. Enter Antonio Gonzalez, president of the Southwest Voter Registration Education Project, a well-established Latino organization that, according to the Los Angeles Times, “has been working in Nevada ahead of the state’s Democratic caucus.” In a press release, Gonzalez took aim at the Clinton campaign’s analysis to justify its claim it won Latino voters: “We note that some analysts have said that Secretary Clinton’s victories in heavily Latino precincts proved that she won the Latino vote. However, the methodology of using heavily Latino or ‘barrio’ precincts to represent Latino voting behavior has been considered ineffective and discarded for more than 30 years due to non-barrio residential patterns common among Latino voters since the 1980’s.”

The press release, as quoted by CounterPunch’s Doug Johnson Hatlem, continued: “The Clinton margin of victory is adequately explained by the large margin of victory Secretary Clinton won among African American voters.… There is no statistical basis to question the Latino vote breakdown between Secretary Clinton and Senator Sanders [in the Edison entrance and exit polling].” Our polling indeed showed that Secretary Clinton won overwhelmingly with African American voters in Nevada. In a phone interview with Hatlem, Gonzalez was more blunt in supporting the results of Edison’s entrance and exit polling showing Bernie winning Latino voters in Nevada: “This whole dispute is baloney. I don’t dispute the Edison numbers at all.”

As the focus moved to South Carolina, the question of which candidate won the Latino vote was left hanging until it was irrefutably demonstrated on March 1 in Colorado. The media narrative was that our campaign had suffered a setback in Nevada. But if anyone back in the summer of 2015 had said that Bernie Sanders would come within 5.3 percent of Hillary Clinton in Nevada, he or she would have been a laughingstock. We were now competing in a new environment, with a 20-point win or greater in New Hampshire and rising expectations. And our first real setback was right around the corner.

* * *

With the loss in Nevada, we were now going to have to fight vote by vote, delegate by delegate, state by state. We went back to the week-by-week schedule that Mark Longabaugh had worked out, and we planned an approach that would provide us with wins every week.

We had some tough decisions to make. We would soon be leaving the phase of the campaign where it was one state at a time. Within a month, we would be competing in eleven contests on a single day, March 1, and less than two weeks after that we’d be competing in five states on March 15. Ohio, Florida, North Carolina, and Illinois had very expensive media markets. And there were important contests in between, including Michigan, which we viewed as critically important. Even with the millions now flowing into the campaign, we could not go full-bore everywhere.

The fourth of the first four states was coming up, but unlike the first three, it was being held only four days before March 1—the date on which ten states and one territory would all cast their votes. This would be followed by four more states before March 8, when Michigan would vote. A week later, big, expensive states would go to the polls. Until we got through South Carolina, the March 1 states, and the next four (Maine, Kansas, Nebraska, and Louisiana), we would not have the luxury of focusing on just one state in terms of Bernie’s schedule.

Our benchmark polls in December of eight of the March 1 contests had been inauspicious. We were down by double digits in every single one. Four of those (Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Oklahoma) were better (we didn’t poll in Vermont, where we assumed we would be strong)—but, in the case of Massachusetts, not wildly better.

We had decided that these five represented our best chance of success on March 1, because we were doing better there, even if better was not great. Massachusetts was particularly troubling. We had run thousands of points of television in the Boston media market in the lead-up to New Hampshire. And we were still almost 20 points down. I met with Tad and Mark, both of whom had Massachusetts-specific campaign experience.

“What can we tell the people of Massachusetts that they haven’t already heard?” I asked.

Tad weighed in. “Don’t worry. We haven’t advertised in the Springfield or Providence markets yet, and when we do you’ll see dramatic movement.”

That didn’t seem right to me, but it turned out to be 100 percent correct.

The week before the New Hampshire primary, Mark Longabaugh and I laid out the states through March 15 on a whiteboard and worked out a preliminary paid media budget. We called Revolution Messaging and got fresh estimates on fund-raising. The all-in strategy of the first four states was not an option. It was not economically sustainable.

We assigned small buys for Kansas and Nebraska. We assigned nothing for Maine, because it was receiving a lot of Boston TV that we were running to reach southern New Hampshire, and we rightly believed we were strong there.

Michigan would be a priority because of its important place in our strategy. We would also make buys in Colorado, Minnesota, and Oklahoma. In Massachusetts, we would focus on the media markets outside of Boston. And in the South, outside of South Carolina and Florida, we would rely on a national cable news buy and African American radio. We just didn’t have the resources to fight with equal intensity everywhere.

On March 15 we would invest in Missouri, Illinois, Ohio, and, to a lesser degree, North Carolina. Florida was another story. We expected Florida to be difficult. It had an older population and it was a closed primary. Also, there is a lot of early voting in Florida. Any meaningful paid media had to be spread over a longer time period to be effective. Finally, it’s expensive. We decided to target advertising in central and upstate regions only.

When we had everything up on the whiteboard, Mark looked at it and then looked at me.

“We are going to be short in a bunch of places,” he said.

“Well, I have to keep a reserve. We can’t spend below $10 million, because I have to be sure we have money until the end,” I replied.

“Okay, well, then, this will have to do,” Mark said, resigning himself to the reality that we both understood. We couldn’t do everything everywhere.

As it turned out, we ended up with more resources than we budgeted that day, but we also spent much more in Nevada than expected when we bumped our spending after New Hampshire.

Shortly before the South Carolina primary we did another round of polling. We were making progress in many states. In Colorado we were now down only 1 point among likely caucusgoers. In Minnesota we were down 9. In Massachusetts we were down 4 (quite an improvement), and in Oklahoma we were down 2. In the fall, Oklahoma Republican senator Jim Inhofe had told Bernie that he would do well there. Senator Inhofe and Bernie are polar opposites, especially when it comes to climate change. Inhofe is a climate-change denier. But they have a cordial relationship.

“You’re going to do well in Oklahoma, Bernie,” Inhofe said.

“Why do you say that?” Bernie asked.

“Because you’ve got to be really liberal to be a Democrat in Oklahoma,” the Republican opined. That wasn’t an entirely accurate assessment of the state of the race in his home state. Oklahoma allowed independents to vote as well.

But we certainly were doing better there. We also had a top campaign manager, Pete D’Alessandro, who had taken the helm there after Iowa. And we also had strong organizations in the other three. Colorado (led by Dulce Saenz) and Minnesota (led by Robert Dempsey) were both caucus states, so a strong ground game was especially important. And Massachusetts was led by Paul Feeney, who had been with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) before the campaign. The other important fact about these three was that the February polls were taken after our paid media campaigns had begun in each. As was the case throughout the campaign, the combination of a strong campaign on the ground and a robust paid media effort made for success.

In the four southern March 1 states that we polled in December (Arkansas, Texas, Tennessee, and Virginia), our February polls showed that, although we had made some progress, none of them were even close. We had people leading our ground efforts in each: (Kelvin Datcher (Alabama), Sarah Scanlon (Arkansas), state representative LaDawn Jones (Georgia), Matt Kuhn (Tennessee), Jacob Limon (Texas), and Peter Clerkin (Virginia). But our limited paid media was a serious problem.

Former NAACP head Ben Jealous, who had joined our effort by then, assisted in the placement of black radio ads. His strong support, including many effective public and television appearances, were critical throughout the primaries.

But our budget constraints hurt. A lot.