1

Tools of the Intellect

Neither the bare hand nor the unaided intellect has much power; the work is done by tools and assistance, and the intellect needs them as much as the hand. As the hand’s tools either prompt or guide its motions, so the mind’s tools either prompt or warn the intellect.

—Francis Bacon, English statesman, lawyer, philosopher and voice of the Scientific Revolution1

In November 1890, the noted English psychologist James Ward boldly stated of mathematics education that: “The individual should grow his own mathematics just as the race has had to do. But I do not propose that he should grow it as if the race had not grown it too. When, however, we set before him mathematics in its latest and most generalized, and most compacted form, we are trying to manufacture a mathematician, not to grow one.”2

An interesting idea indeed, but it was already very old even by Ward’s time. Believe it or not, traces of this idea can be found way back in the 1600s in the writings of the great Czech educator John Amos Comenius, as well as many others since (and a few before). In this chapter, we aim to implement a portion of this grand vision of math education by attempting to grow the reader’s understanding of basic numeration in a natural and contextual manner as opposed to manufacturing it artificially. Let’s see if it works.

We begin with a simple question: What exactly is a numeral? Is it the same thing as a number? If not, what’s the difference? Put to mathematics, this may seem like a subtle question but it is essentially a question about the difference between a thing and the symbolic representative of that thing. For example, it is easy to see that an actual physical house is vastly different from the five letter word “house” that represents it in English. The word in fact doesn’t look anything like the structures it describes.

In a similar fashion, numerals are symbols that we use to represent numbers but aren’t the actual numbers themselves. Defining exactly what a number is can be tricky. The good news is that our intuitive notion of what numbers are is more than adequate for our purposes here. For example, whether or not we can give an exact definition of the number three doesn’t prevent us from recognizing when a collection has three objects. In this text, we will often blur the distinction between number and numeral, but this should cause no difficulties.

It is worthwhile noting, however, that when the distinction between the two has been blurred this has sometimes led to important mathematical discoveries (we will see this happen in chapter 3 when we illuminate the discovery of zero), while in other cases it has led to untold conceptual difficulties and superstitions (some of which also came with the discovery of zero).

In any event, it is useful to keep in mind that there is the concept of a number (say three) and many different ways to represent that number (three, tres, | | |, 3, etc.); just as there are many different ways to represent the concept of greeting someone (e.g., hello, hi, buenos dias, ni hao, konnichiwa, guten tag, namaste, and so on).

Organizing Tally Marks

Throughout this book, we will be primarily concerned with numerals that represent a number by some sort of written mark. When we decide to represent numbers this way, we gain advantages in efficiency—over other methods such as direct comparison or using rocks. Moreover, by using visible marks we acquire the ability to more easily lay out side by side the symbols for the various sizes; which allows us to analyze how different magnitudes compare in a visual way. Implementing this scheme by going from smaller values to larger values yields the following system of tally mark arrangements:

Now, let’s say we wanted to count a collection of ten apples. We could do this by simply jotting down a tally mark for each apple and this might look like: | | | | | | | | | |. Since the number of tally marks is the determining factor in conveying size, not their horizontal or vertical appearance, this arrangement is equivalent to the one in the previous diagram given by:  . We see then that the number ten is represented in the system of tally mark arrangements listed above.

. We see then that the number ten is represented in the system of tally mark arrangements listed above.

While giving us greater leeway than the original methods of comparing size (via lanes and rocks), using tally marks still has some serious inconveniences. This can be seen when tally marks are used to represent relatively large collections, say for instance one thousand.

Think about it, placed side by side would you be able to quickly distinguish the difference between a collection containing one thousand tally marks and a collection that had one thousand and three tally marks? You would be a rare specimen indeed if you could. Humans simply aren’t built to quickly gauge such differences on sight. We know that we can resort to a matching off process but this is laborious and unpractical. Can we build tools of some sort to help make such differences more readable to us on sight?

Societies throughout the ages have faced this question and chose a variety of ways to deal with it. A natural approach, when the number of tally marks became large enough, involved rearranging them into equally sized groups. If we apply this approach to the largest two collections shown in the bottom row of the tally mark arrangements, we obtain many possibilities. Three rearrangements are listed here:

Groups of five:

Groups of seven:

Groups of ten:

Each of these rearrangements allows us to determine, more quickly, which collection of the two is larger (twenty-three versus twenty-five). Such tallies are frequently done in counting votes and the like; and to simplify matters even further, each of the rows of equal size is often struck out by a diagonal line, which is also included as a tally mark in the count. Thus our rearrangement into groups of five can be written as:

Groups of five (rows slashed):

Similarly, our seven and ten groupings can be written as:

Groups of seven (rows slashed):

Groups of ten (rows slashed):

More conveniently, we could replace each of the rows of constant size by a new symbol. Thus, for example, in the first case we may replace the rows of size | | | | | by the symbol  . Doing so compresses the symbols used to:

. Doing so compresses the symbols used to:

Five coins:

Similarly, replacing the groups of sizes | | | | | | | and | | | | | | | | | | by the respective symbols  and

and  in the latter two examples yield:

in the latter two examples yield:

Seven coins:

Ten coins:

Compare the readability of the coin diagrams with the original ungrouped tally mark diagrams. The size of the groupings chosen in this manner is called the base of that system. Thus the reorganizations into groups of five, seven, and ten correspond to systems of base five, base seven, and base ten, respectively.

While there is complete freedom in which system of grouping or base to use, most societies in the past chose to group in fives, tens, or twenties as opposed to other groupings such as sevens or twelves. Why is that?

The common belief is that these choices were made due to the nature of human anatomy. The human beings devising these systems had five fingers on one hand, ten fingers on two, and ten toes on two feet. It seems reasonable that these appendages would be used to aid in the counting, and that people would naturally choose groupings that matched the number of fingers and/or toes in a one to one fashion.

A good test of this theory could occur sometime in the future: If we were to ever meet an alien species of beings with say seven fingers on each hand and seven toes on each foot. The theory would predict that popular bases for this species would be seven, fourteen, and twenty-eight (assuming we didn’t destroy each other first before we could find out).

We will use base-ten grouping throughout the book. Accordingly, any collection of tally marks numbering less than ten is left as it occurs, thus we will leave the arrangements { | | | | | , | | | | | | | } as they are but will replace the arrangement with ten tally marks { | | | | | | | | | | } by the  symbol or the arrangement with twelve tally marks { | | | | | | | | | | | | } by the coins

symbol or the arrangement with twelve tally marks { | | | | | | | | | | | | } by the coins  (where we have replaced ten of the tally marks by the ten coin symbol, leaving as is the two left over). Whenever a group of ten tally marks is encountered in any configuration we will so replace them by the

(where we have replaced ten of the tally marks by the ten coin symbol, leaving as is the two left over). Whenever a group of ten tally marks is encountered in any configuration we will so replace them by the  symbol.

symbol.

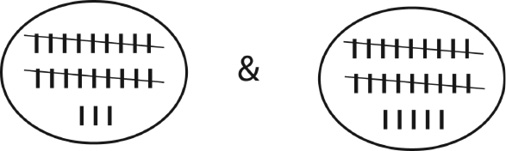

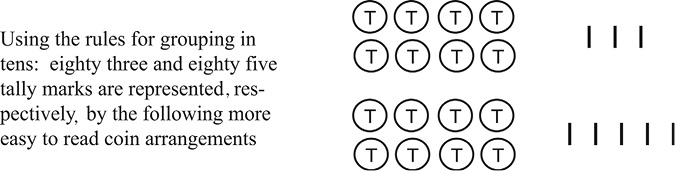

Using these grouping rules now gives us the ability to quickly and easily distinguish between a coin configuration containing, say, eighty-three tally marks and one containing eighty-five. Not the case, however, if we leave these coin configurations ungrouped, as eighty-three |s and eighty-five |s, respectively.

This problem of comparison is not unique to the |s. The essence of the difficulty lies with the proliferation of symbols. It is hard for us to quickly compare eighty-three and eighty-five of any type of symbol. So if we have eighty-three and eighty-five  s, we will still have the same problem.

s, we will still have the same problem.

The process of gauging or measuring the size of a collection on sight without counting is called subitization. Think about it, you can probably recognize at most four or five objects at a glance. Ask yourself, and be honest now, can you look at a collection of thirteen objects and recognize instantaneously that there are exactly thirteen of them without counting or rearranging them in some way?

Some experimental results suggest that our ability to recognize a certain number of objects on sight is an innate talent that we possess from a young age. In a particularly interesting study reported in Nature magazine in 1992, reaction times of four- to five-month-old infants were investigated by a University of Arizona researcher. The infants paid much longer attention to situations involving size that violated what they evidently expected to see. For instance, a puppet was shown to the child and then hidden behind a screen. Then a second puppet, in full view of the infant, was placed behind the screen. When the screen was removed and only one puppet was present, as opposed to the two puppets, the infants paid much longer attention to this situation than they did to the expected situation of two puppets being present. Similar observations were observed, for instance, when two puppets were expected and three were shown. This suggests that the infants could distinguish between one and two and between two and three (and that they even understood that one plus one should be equal to two not one or three).3 Other studies have since both confirmed and questioned these findings.4

We have made the arrangements represented by:

more readable by invoking our base-ten grouping rules and rewriting them as:

Can we do the same if we are confronted with twenty-three  s and twenty-five

s and twenty-five  s as shown here?

s as shown here?

An obvious way to make this situation more readable would be to similarly represent a group of ten of the  coins by a new symbol. This we do and get:

coins by a new symbol. This we do and get:

The “H” of course stands for one hundred and using this new grouping allows us to rewrite the twenty-three tens and twenty-five tens, respectively, as:

The symbols on the right represent the larger number of two-hundred and fifty versus the smaller value on the left of two-hundred and thirty. This form of writing the values is easy to read and once again allows us to immediately recognize which number is greater.

If the sizes are great enough, the problems we have with the  s will reappear again with the

s will reappear again with the  s unless we also group them and so on. Thus continued grouping into higher coin denominations is an obvious choice if we want to handle larger and larger numbers more conveniently. Historically, as societies grew more complex they had to deal with ever-increasing numbers, leading to the creation of not just one type of coin numeral but to many types—or to a system of coin numerals. The natural progression of our system is listed here:5

s unless we also group them and so on. Thus continued grouping into higher coin denominations is an obvious choice if we want to handle larger and larger numbers more conveniently. Historically, as societies grew more complex they had to deal with ever-increasing numbers, leading to the creation of not just one type of coin numeral but to many types—or to a system of coin numerals. The natural progression of our system is listed here:5

ten ≡

hundred ≡

thousand ≡

ten thousand ≡

hundred thousand ≡

million ≡

Imagine trying to understand, without any grouping, the individual tally marks represented by:

This number in English reads as two million, two thousand, one hundred twenty-one and in grouped form we can grasp what value it represents with ease. Without the aid of grouping, we are as helpless mentally to grasp its value as a logger would be in a forest without the aid of his chain saw or ax.

Representing numbers by grouping doesn’t save us the trouble of having to do the initial count, however. If there are eight hundred thirty-five objects randomly assorted, the first person to learn this must perform the actual tally. However, once the result is obtained, grouping allows her to rearrange the tally marks, via the methods discussed here, and record them in a more accessible fashion for future use. That is, this grouping saves others, including herself, who need to reference the information, from having to perform the long count all over again. If the eight hundred thirty-five objects are arranged in a neat pattern, we may be able to determine the number of objects without actually counting each one; we’ll talk more about how to do that in chapter 6.

This simple process of rearranging larger groups of tally marks into smaller sets of coins hints at the fantastic capabilities for transformation that ideas about quantity can acquire when we represent them by certain types of visible marks. We can systematically with ease take the visible marks places that it would be very difficult, if not impossible, to take the things that they stand for. This allows us to literally reshape ideas in reproducible ways (one thousand individual tally marks being instantaneously morphed into the single symbol  while the thousand individual physical items that the symbols stand for remain unchanged)—refashioning them so as to gain huge conceptual and, as we shall soon see, computational advantages while not losing any essential content.

while the thousand individual physical items that the symbols stand for remain unchanged)—refashioning them so as to gain huge conceptual and, as we shall soon see, computational advantages while not losing any essential content.

It’s just like money. Money allows us to equate all sorts of different things and represent them by a single dollar value. Eight hundred dollars can represent a rent payment, the price of a television set, the price of a computer, the wages for forty hours of hard work, a car repair bill, or the price of a meal at a campaign fund-raising event. These different things become equivalent in the sense of monetary value. This equivalence allows a laborer to systematically transform his forty hours of hard work into a television set, a rent payment, a set of new brakes, or a computer. Money, in a sense, acts like a liquid by allowing his forty hours of sweat to seamlessly flow into another form to great advantage (in this case a form involving the necessities or luxuries of life). In fact, assets in the form of cash are often called liquid assets. Symbols in arithmetic act like a currency for quantitative ideas.

Ancient Numeral Systems

We have discussed one possible way of making the sequence of sizes for collections more readable. There are a myriad of others. One of these is the Egyptian hieroglyphic system. The hieroglyphic method of numeration is similar in spirit to the coin system of numeration discussed earlier. The following table shows the coin denominations and their hieroglyphic equivalents.

Permission to use hieroglyphic symbols granted by William Hatch.

Using this system, the number two million, two thousand, one hundred twenty-one would read as:

The number twenty-three thousand, three hundred twenty-two in hieroglyphics would read as:

Another ancient system of numeration is the well-known Roman numeral scheme. The Roman system uses “I” as its basic tally symbol. Thus the side-by-side layout of magnitudes with this symbol is given by:

I II III IIII IIIII . . . IIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIII . . .

It is clear that the Romans faced the same problem with the proliferation of symbols as we did earlier. The Romans chose to also deal with this problem by grouping—converting a certain collection of tally marks into a new symbol; but they did so in a manner somewhat different from our coin system. Their first grouping occurred at five, with the symbols IIIII being replaced by the symbol V. However, instead of continuing to group in fives and creating a new grouping symbol for VVVVV, the Romans created a new grouping symbol for only two of them, replacing the symbols VV by the symbol X. This alternation between five grouping and two grouping continues in the Roman scheme; indicating the use of fingers and hands (which come in fives and twos, respectively).

The following is a list of Roman symbols and how they represent magnitudes up to one thousand:

(One): I

(Five=Five ones): IIIII ≡ V

(Ten=Two fives): VV ≡ X

(Fifty=Five tens): XXXXX ≡ L

(Hundred=Two fifties): LL ≡ C

(Five Hundred=Five hundreds): CCCCC ≡ D

(Thousand=Two five hundreds): DD ≡ M

Unlike our coin scheme which is purely additive (i.e., we add the coin values in a configuration to obtain the value represented), Roman numerals can also employ a subtractive feature. Thus for instance one may write:

four as IIII (four ones) or as IV (five minus one)

nineteen as XVIIII (fifteen plus four) or as XIX (ten plus ten minus one)

nineteen hundred as MDCCCC (fifteen hundred plus four hundred) or as

MCM (one thousand plus one thousand minus one hundred)

The convention in general is that larger value symbols are written to the left of smaller value symbols. If a smaller value symbol is to the left of a larger value symbol, it means subtraction of the smaller value from the larger. Thus XXXI means thirty-one whereas XXIX means twenty-nine. Numbers larger than one thousand can be dealt with by placing a bar over the number, which means to multiply by one thousand. Thus

V

means five thousand and

L

means fifty thousand.

It is worth noting, however, that much variation has existed in some of these rules throughout the centuries. For instance, the subtractive principle appears to have been rarely practiced in ancient Rome itself, and several methods, in addition to the one discussed above, have been used to represent numbers greater than a thousand.6

Roman numerals, of course, still find considerable usage today. They serve as visually elegant representations of numbers, and are sometimes used in movie credits, on clocks, for the labeling of Super Bowls, and as page numbers in the prefaces and introductions to books. They are not used, however, to perform calculations.

Six hundred seventy-two is represented in the three systems as follows:

DCLXXII

What is the base of the Roman numeral system? Since two types of groupings are used, which has the priority? Is it a base-two system, a base-five system, or something else? Essentially, the Roman numeral system is what might be called a modified base-ten system. That is, all the base-ten groupings of our coin system (ones, tens, hundreds, thousands, ten thousands, etc.) are present in the Roman system (using bars for values larger than a thousand) but there are extras: five, fifty, five hundred, and so on.

As a standard of comparison, think about the American monetary system which is a decimal or base-ten system with modifications—that is, we have the base-ten denominations of the penny (the equivalent to the basic tally mark), the dime, the dollar bill, the ten dollar bill, the hundred dollar bill, and so on, but we also have the nickel, quarter, five dollar bill, and twenty dollar bill.

These extra or interior denominations help keep the change in our wallets and purses more manageable and so too do they help keep the strings of Roman numerals down to a more manageable size. This is an advantage of the Roman system over the other two we have discussed. This can be clearly seen in the representation of six hundred seventy-two in the three systems (where the coin and Egyptian systems require fifteen total symbols while only seven Roman numerals are needed).

Another ancient system of numeration, which we will briefly visit later in chapter 10, worked by grouping in packets of sixty. That is, instead of being base ten, the system was what we might call a modified base-sixty system. This is the famous sexagesimal system of the Sumerians, and subsequently the Babylonians, developed more than four thousand years ago. The system was a mix of additive grouping and place-values, thus differing in a fundamental way from the three systems discussed earlier.

Awkward as it may sound, this system was so versatile, due to the place-value component, that remnants of it survive to this very day. For example, in our methods of reckoning time, we group both minutes (the small or “minute” part of an hour) and seconds (the “second” small or minute part of an hour) in packets of sixty.

Conclusion

We have progressed far from the pedestrian task of comparing two herds of cattle. The work done on the ranch clearly has had far-reaching implications. Starting from the methods developed there, we now have a coin numeral system allowing us to conveniently represent the quantity in any discrete collection we are likely to ever encounter in daily life. Moreover, we can use these representations to compare the sizes of various collections and communicate these results in a visible way. The ranchers in satisfying their curiosity to know which of them had the larger herd were actually touching upon universal situations that can all be dealt with in a similar fashion—meaning that they were, in a sense, able to dial into eternity from down on the ranch.

The requirements for using a manageable set of symbols are based in large part on psychological needs. We simply cannot easily distinguish the differences between collections of even modest size unless we arrange them in some fashion. Ultimately, however, we are still fighting a losing battle. Given that numbers go on without end, even our technique of grouping will result in a proliferation of symbols that will eventually overwhelm, as we try to describe larger and larger numbers.

The coin system or even the place-value system we use today, while simple to learn and rich enough to describe most of the numbers we need in everyday life, are not so well suited to describe some of the numbers that scientists and engineers need on a daily basis. Consequently, they often use other notational schemes to keep the number of symbols down to a manageable size. Scientists often use a system called scientific notation while others often use a slightly different version called engineering notation.

Finally, the ability to share information in a visible way turns out to be highly nontrivial. In language, the ability to communicate visibly turned out to be revolutionary; perhaps as revolutionary a thing as there has ever been designed by the hand of man. In the next chapter we discuss some of the gains that we acquire from communicating this way.