6

The Symmetry of Repetition

The whole object of travel is not to set foot on foreign land; it is at last to set foot on one’s own country as a foreign land.

—Gilbert Keith Chesterson, British author, literary and social critic1

We eat three meals a day, go to work five days out of seven, and grocery shop perhaps once a week—repetitive acts are a part of life. Have you ever wondered how many times you do each of these in a year? How would you go about counting something like that? Trivial you say? Think again, for once more, we are close to touching upon timeless principles: touching upon those “special cases” of David Hilbert’s, if you will—the ones containing all the germs of generality.

In this chapter, we will find that figuring out how to conveniently count repetitive actions or situations leads us onto the trail of an entirely new way of reckoning—called multiplication. We begin by considering the following:

A. A bookstore receives a regular shipment of 15 boxes of books every week. How many boxes are delivered in one year?

B. The setup for a graduation ceremony has 30 rows each with 45 chairs. How many guests can be seated at the ceremony?

C. What is the total amount paid back on a signature loan of 36 months where each payment is $115?

D. A 2001 Chevrolet Impala gets 25 miles per gallon. If it has a gas tank which holds 17 gallons, how many miles can it travel when full?

E. A country has a population of 26,784,000 (approximately the same number of people as Nepal in 2011). If the average per capita income is $17,200, what is the combined income in one year for all of its citizens?

These five problems have something in common with our questions about weekly routines; and most people would answer that each can be solved by multiplication. But what exactly does that mean? If a child asked you what multiplication is about, could you explain it? If we knew nothing of multiplication and could only add and subtract, would we still be able to find the answers to these questions?

While each of these problems deals with a different issue, they can be solved by addition alone—provided we add together the number involved in the repetitive act the required number of times. For question:

A. The repetitive act is a shipment of 15 boxes every week for a year (52 weeks in a year); for the answer we must add fifty-two 15s together.

B. The repetitive act is 45 chairs in each of the 30 rows of chairs in the auditorium; for the answer we must add thirty 45s together.

C. The repetitive act is a payment of $115 for each of the 36 months of a loan; for the answer we must add thirty-six 115s together.

D. The repetitive act is 25 miles for each of the 17 gallons of gas in the fuel tank; for the answer we must add seventeen 25s together.

E. The repetitive act is $17,200 for each of the 26,784,000 citizens in the country; for the answer we must add twenty-six million, seven hundred eighty four thousand 17200s together.

The need to repeatedly add or count in multiples occurs in numerous guises.

There are millions upon millions of other situations (an infinite nation of them if you will) that can be linked by the need to repeatedly add numbers together and this fact alone makes this process highly relevant. As with Amar, when he began studying circles: Whatever we discover in our study should have far-reaching, even universal, implications.

But first we need to give chase to the common thread running through all of these problems. What is it? Each of the problems involves a “certain number of objects” (boxes, chairs, miles, or dollars) repeatedly used a “certain number of times.” These two numbers are what we must capture in representing this common thread. In other words, we must identify: the “number of times the repetitive act occurs” and the “number of objects involved in each repetitive act.”

For the situation involving bookstore shipments the repetitive act occurs 52 times and 15 objects are involved in each repetitive act. Commonly used abbreviations linking these two numbers include: 52 × 15 or 52 • 15 or (52)(15). Each of these reads as: add fifty-two 15s together or 52 times 15. In the same spirit, we could rewrite the “total combined income” question as 26,784,000 times 17,200 or 26,784,000 × 17,200. These shorthand abbreviations are written representatives of a new process—one that is different and distinct from simple addition or simple subtraction. We will christen the method with the name “multiplication.”

While we may jump for joy over this christening, with its shorthand notation, it really isn’t very helpful in and of itself. That is, if the only way to calculate 26,784,000 × 17,200 is to literally take twenty-six million, seven hundred and eighty-four thousand 17,200s and add them together, then using this abbreviation hasn’t really given us anything new from the standpoint of saving us work—we still have to do all of the additions to solve problems.

Solving the problem this way is simply out of the question: There are 26,784,000 seconds in 310 days, and it most surely would take a longer time than this to simply count from 1 to 26,784,000—even if that is all one did 24/7.2 Since it takes more time to add than to count, it stands to reason that performing these many repeated additions of 17,200 in a direct manner (without any shortcuts) would take a great deal longer than 310 days—even using our modern method of doing addition.

Nevertheless this type of problem remains and needs to be solved. What are we to do? We know many of our ancestors got around this problem by using devices such as the abacus to help them multiply. But we have also shown that the HA numerals are a direct capture of a certain type of abacus in writing. Is it possible to now take advantage of this and avoid actually scribbling down a string of numerals the required number of times—making convenient multiplication in writing possible? If so, this would be a bonanza indeed.

In this chapter, we begin an investigation into whether this is possible or not, and will follow G. K. Chesterson’s lead by looking at the familiar territory of multiplication as if we were strangers in a new land.

Egyptian Multiplication

Our task looks daunting. We have to engineer a way to compute on paper (or some other writing medium) the net effect of doing lots of additions, potentially numbering in the millions, without actually performing all of those additions. Is such a path even possible? Since the abacus already does such an adequate job, why should we even care? Many civilizations didn’t—the methods using a device worked for them and that was good enough.

Nevertheless, performing multiplication in writing is not something we should take lightly. Language writing opens up to us whole new ways of looking at the world and so too might the ability to multiply in writing.

How should we proceed?

We start by asking a simple question of multiplication—does the order in which we multiply make a difference in our answer? We know that order doesn’t matter in addition; for example, we get 13 whether we add 4 + 9 or 9 + 4. This quality of addition is called the commutative property. Subtraction evidently does not have this property since 6 – 2 = 4 and 2 – 6 does not. The latter subtraction doesn’t even make sense for whole numbers, that is, when it is applied to collections such as a group of people or a collection of cell phones.3

It would be fabulous if the order in which we multiply two numbers gave the same answer, since it would mean that 825 × 2 gives the same value as 2 × 825, which would imply that adding “825 twos” together is equivalent to adding “2 eight hundred and twenty fives” together. The latter requires the addition of only two numbers! Put another way, if the order in which we multiply doesn’t change our answer, then we can find the net effect of adding 825 numbers together by simply changing our viewpoint and adding together only 2 values.

We address the question of order in multiplication by considering an example. We use coin numerals for conceptual illumination: Does 4 × 2 = 2 × 4?

These are equivalent. In fact, if we make the columns in B into rows and the rows into columns, we obtain A.

The process of converting rows to columns and vice versa is called “taking the transpose.” Thus the transpose of the result in B is equal to the result in A. Similarly, the transpose of A is equal to B. We clearly see that 4 × 2 = 2 × 4 = 8.

This example illustrates what is true in general—the order in which we multiply two numbers makes no difference in the final answer. The order in which we repeatedly add or multiply, however, does make a big difference in how convenient a time we have in obtaining that answer. Using this basic property in the per capita income situation, we can find the value of 26,784,000 × 17,200 (requiring that we add 26,784,000 numbers together) by simply reversing the order and calculating 17,200 × 26,784,000 instead (requiring that we only add 17,200 numbers together).

The equality of these multiplications quite naturally connects the total income of two radically different nations, one with a large population of more than 26 million where the average citizen has an annual salary of $17,200 (below what is considered the poverty line for an American family of four), with a very rich nation of only 17,200 citizens where each earns on average $26,784,000 per year.

Taking a situation that requires more than 26 million additions and transforming it to one that requires 17,200 is no small feat. Unfortunately, this is still way too many to make brute force repeated addition a practical way to solve problems that involve many repetitive acts.

Remarkably in the time of the pharaohs, the ancient Egyptians developed a systematic way to perform fewer additions in writing. Their technique sheds light on an important property of multiplication so we will discuss it in some detail here.

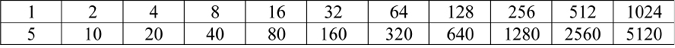

The method is based on the principle of doubling and requires forming two rows. The values in the top row are obtained by starting with the number one in the first cell, and repeatedly doubling the result as we move across the row—thus, doubling 1 yields 2, doubling 2 yields 4, doubling 4 yields 8, and so on. We list the results in the top row up to 1024:

Doubling Table

The bottom row will change values depending on the number repeatedly added. Let’s look at this for the case where the number is 5. The numbers in the bottom row are obtained by starting with the number 5 in the first cell and doubling as we move across the row.

Doubling Table for 5

This is a times table of sorts for 5, since for example 5 × 8 = 40 and the 40 lies below the 8. Believe it or not, from just the 11 entries in the bottom row we will be able to calculate the value of 5 times any number between 1 and 2047.4 The two examples of 14 × 5 and 642 × 5 show how this works:

Doubling Table (14 × 5)

To use the table to compute 14 × 5, we first scan the top row for numbers that add up to 14 and find that 8 + 4 + 2 = 14.

Next, we add the numbers in the lower row which lie below each of these to obtain: 40 + 20 + 10 = 70. We conclude that 14 × 5 = 70.

Expanding this sum illustrates conceptually what is happening.

To find 642 × 5, we scan the top row of the table for numbers that add up to 642 and find that 512 + 128 + 2 = 642.

Doubling Table (642 × 5)

We add the numbers in the lower row which lie below each of these to obtain: 2560 + 640 + 10 = 3210. We conclude that 642 × 5 = 3210. Note that 2560 contains 512 fives and 640 contains 128 fives and 10 contains two fives. Hence their sum contains 642 fives which is our goal.

To see the generality of this method we now construct a doubling table for 45 and use it to compute 1584 × 45:

Doubling Table for 45

We scan the top row to find the numbers adding up to 1584 and find that 1024 + 512 + 32 + 16 = 1584.

Doubling Table (1584 × 45)

We add the corresponding numbers in the bottom row to obtain: 46080 + 23040 + 1440 + 720 = 71280. We conclude that 1584 × 45 = 71280.

From the definition of multiplication as repeated addition, we can find 1584 × 45 by either adding 1584 (45s) together or by reversing the order and shortening it to adding 45 (1584s). Adding together forty-five numbers is still more work than we would like to do. Using the procedure from ancient Egypt allows us to find the answer (after the table has been constructed) by adding together only 4 numbers. That’s right, only 4! Pretty clever of the ancients! The amount of effort saved is even more substantial when larger numbers are involved.

In illustrating the Egyptian method here, we have used our modern day HA numerals. The Egyptians of course did not know these numerals and would have used some other set. It turns out, in fact, that the Egyptians had several types of numerals, including the hieroglyphic numeral system discussed earlier as well as a cursive form of numerals called hieratic. They evidently used hieratic numerals when performing the doubling method. The doubling method is demonstrated in one of the oldest known surviving documents on mathematics—the Rhind Papyrus. Based on an even earlier document, the work is estimated to have been written around 1650 BCE by a scribe named Ahmes.5

The Egyptian method convincingly demonstrates that we can obtain answers to multiplication problems in systematic ways that don’t require doing all of the additions in writing. In fact, “17,200 × 26,784,000” can now be solved by many within 15 to 25 minutes of using it. The simple and ancient method of doubling, combined with the commutative property of multiplication, has accelerated a process that in its original form would have taken several hundred days to perform using brute force repeated addition to one that can now be completed on a few sheets of paper and in less time than it takes to watch a single rerun of The Cosby Show. That’s an exceptionally cool thing.

The Distributive Property

Crucial to the success of the Egyptian method is the distributive property of multiplication over addition. To illustrate how the doubling method works, we will first break down a couple of multiplications by 11. We start with 11 × 5; 11 × 5 means to add 5 together 11 times:

5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5

11 fives

We have a lot of freedom in how we choose to add these eleven fives. We can do it by first adding five of the 5s together in one group and six of the 5s in the second group and then combining the results together to obtain 55:

|

5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 |

+ |

5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 |

= |

11 × 5 |

|

5 fives |

|

6 fives |

|

|

|

5 × 5 |

+ |

6 × 5 |

= |

55 |

|

25 |

|

30 |

|

|

We can also arrange the numbers in the following two ways as well:

|

5 + 5 + 5 + 5 |

+ |

5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 |

= |

11 × 5 |

|

4 fives |

|

7 fives |

|

|

|

4 × 5 |

+ |

7 × 5 |

= |

55 |

|

20 |

|

35 |

|

|

or

|

5 + 5 |

+ |

5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 |

= |

11 × 5 |

|

2 fives |

|

9 fives |

|

|

|

2 × 5 |

+ |

9 × 5 |

= |

55 |

|

10 |

|

45 |

|

|

Given that 11 can be broken up into 5 + 6, 4 + 7, or 2 + 9, the above suggests that we can calculate “11 × 5 = 55” directly or by using any of these subdivisions of 11. We will get 55 no matter which route we choose to take.

This is where the doubling table for 5 in the Egyptian method comes in (see the following abbreviated table):

Abbreviated Doubling Table for 5

The fact that 11 equals 8 + 2 + 1 means that we can break up adding the eleven 5s into groups that are already listed in the table. This allows us to swiftly conclude that:

|

11 × 5 |

= |

(5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5) |

+ |

(5 + 5) |

+ |

(5) |

= 40 + 10 +5 = 55 |

|

11 fives |

|

8 fives |

|

2 fives |

|

1 five |

|

Similarly the fact that 8 + 4 + 2 + 1 equals 15 means that we can break up adding the fifteen 5s into groups that are also already given in the table. We swiftly conclude again that:

|

15 × 5 |

= |

(5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5 + 5) |

+ |

(5 + 5 + 5 + 5) |

+ |

(5 + 5) |

+ |

(5) |

|

|

15 fives |

|

8 fives |

|

4 fives |

|

2 fives |

|

1 five |

|

|

|

= |

40 |

+ |

20 |

+ |

10 |

+ |

5 = 75 |

|

Critical to making this doubling procedure work is that the numbers 1, 2, 4, and 8 supply complete coverage of every whole number between 1 and 15 (i.e., any number between 1 and 15 can be written as a sum involving only 1, 2, 4, and 8):

Coverage of Whole Numbers from 1 through 15

This implies that multiplying 5 by any number between 1 and 15 can be obtained by adding some combination of the four elements in the doubling table for 5. This can easily be extended to coverage of the whole numbers between 16 and 31 by simply appending another entry to the doubling table:

Appended Abbreviated Doubling Table for 5

The reader should note that all whole numbers between 1 and 31 can now be obtained from some combination from the top row of this expanded table (e.g., 27 = 16 + 8 + 2 + 1 and 23 = 16 + 4 + 2 + 1). This implies then that multiplying 5 by any number between 1 and 31 can be also obtained from some combination from the bottom row of the table (e.g., 27 × 5 = 80 + 40 + 10 + 5 = 135 and 23 × 5 = 80 + 20 + 10 + 5 = 115).

This process continues with the next two entries in the top row being 32 and 64 supplying expanding coverage of the whole numbers from 1 to 63 and then from 1 to 127, respectively. Continuing on ad nauseum, we eventually cover all of the whole numbers, meaning that we can in principle use the doubling table to calculate any multiplication involving the number five (see www.howmathworks.com for more sample problems and explanation of many of the examples given in this chapter).

There is nothing special about five. These methods will work for any whole number. The sums in the top row in these tables remain. The only change would be to replace the doubling of 5 in the bottom row by the doubling of the number in question. Hence, the Egyptian method gives us a complete recipe for how to multiply any two whole numbers in writing. This recipe enables us to get around the issue of having to perform all of the repeated additions. It is a stunning achievement of ancient Egyptian mathematics!

In spite of its success, however, this method is not the main event here. The high point of our discussion on multiplication will center on how it works using the “alphabetic” features of the HA system. For it is here that the symmetries of the ancient Indian system get fully unleashed— elevating the ability of human beings to circumvent repeated addition in writing to a high art.

Multiplication in Place-Value Systems

Place-value multiplication is devastatingly effective on multiple fronts. If the Egyptian method were likened to conventional explosives, then multiplication using the alphabetic features of HA numerals is nuclear. The HA conquest of multiplication depends on these key components:

1. The distributive property of multiplication over addition

2. The existence of convenient footholds into which we can naturally decompose any number

3. The symmetry of the positional system

To take full advantage of these three components requires that we:

A. Make multiplication alphabetic (as we did with addition) by constructing a “times” table.

B. Devise an efficient algorithm (that takes advantage of these alphabetic features) which is compact and straightforward to learn.

We have discussed the distributive property and also the existence of convenient footholds in the case of the Egyptian scheme (the entries in the top rows of the doubling tables). In the HA system, the convenient footholds are the place values, themselves, corresponding to 1, 10, 100, 1000, 10,000, and so on. We are going to use the footholds here a bit differently than in the Egyptian case.

Alone, the footholds corresponding to the place values cannot be combined in the Egyptian way. What the place values offer, however, is a much more natural decomposition of a number. This decomposition is, of course, their raison d’être. Before beginning, it will prove useful to introduce two hybrid or mixed numeral representations that will help provide critical conceptual understanding throughout our discussion of both multiplication and division. The decomposition of 625 illustrates these representations:

Multiplying a place value by a given number is very straightforward as the multiplications of 1, 10, and 100 by 3 show:

For each calculation notice that the same thing happens—multiplication by 3 converts one bead (●) into three beads  , the only difference being the location of the rod on which it occurs.

, the only difference being the location of the rod on which it occurs.

For 3 × 1, this conversion occurs on the rod in the ones place. For 3 × 10, this conversion occurs on the rod in the tens place. For 3 × 100, this conversion occurs on the rod in the hundreds place. This identical behavior in different locations again illustrates the symmetry of our positional system. It is also worth pointing out that multiplication by 3 has no effect on the vacant rods (represented by a zero in HA script), only on the rod which contains a bead—yielding three beads plus the vacant rods. In HA notation, this translates to a value of 3 followed by the number of zeros in the place value. Using this same observation we readily conclude that 3 × 10000 will yield a 3 followed by four zeros or 30000.

There is nothing special about 3; the same result holds for any number. Namely, multiplying any number by the place values (1, 10, 100, 1000, etc.), yields a value starting with the number followed by the quantity of zeros in the particular place value. Thus 12 × 10000 gives 12 followed by four zeros or 120000.

We have discovered a fundamental pattern from observing the behavior of the abacus rods for the multiplications: 3 × 1, 3 × 10, and 3 × 100. There are dozens of other fundamental patterns to be revealed. Let’s look for the one yielded in the multiplications of: 4 × 3, 4 × 30, and 4 × 300 (we now add vertically for increased clarity):

The pattern this time is:

4 ×  yields

yields  .

.

For 4 × 3, the situation is played out on rods one and two. For 4 × 30, the situation is played out on rods two and three. For 4 × 300, the situation is played out on rods three and four. In HA script, this fundamental pattern reads as 4 × 3 =12. Once this is known, we can handle any situation involving 4 times a number that has 3 as its only nonzero digit. We do this by simply leading with 12 followed by the correct amount of zeros (e.g., 4 × 3000000 = 12000000).

The fundamental pattern for 6 × 7 is:

6 ×  =

=  .

.

For 6 × 7, this pattern is played out on rods one and two, while for 6 × 70, this pattern is played out on rods two and three and so on. In HA script, this fundamental pattern reads as 6 × 7 = 42. From this we can handle any situation involving 6 times a number that has 7 as its only nonzero digit. We do this by simply leading with 42 and following it by the correct amount of zeros (e.g., 6 × 7000 = 42000).

There are more jewels to be uncovered here (than might first appear on the surface) from the knowledge of the two fundamental patterns for 4 × 3 = 12 and 6 × 7 = 42. We can now project these patterns to handle many, many more complicated multiplications. Let’s see this play out on the multiplication of 33 × 4—using the basic pattern that 4 × 3 = 12, the distributive property, and the knowledge that reversing the order in which we multiply doesn’t change our answer:

|

33 × 4 |

= |

30 × 4 |

+ |

3 × 4 |

= |

4 × 30 + 4 × 3 |

|

Add thirty three 4s |

|

Add thirty 4s |

|

Add three 4s |

|

|

Using both abacus rod and HA script in parallel yields:

This gives 33 × 4 = 132. We easily extend this to the multiplication of 333 × 4 by writing this as:

|

333 × 4 |

= |

300 × 4 |

+ |

30 × 4 |

+ |

3 × 4 |

= |

4 × 300 + 4 × 30 + 4 × 3 |

|

Add 333 4s |

|

Add 300 4s |

|

Add 30 4s |

|

Add 3 4s |

|

|

and doing the same thing as above we obtain 333 × 4 = 12 + 120 + 1200 = 1332. Try it on the rods yourself.

In the same vein, the fundamental pattern 6 × 7 = 42 allows us to calculate 777 × 6 as follows:

|

777 × 6 |

= |

700 × 6 |

+ |

70 × 6 |

+ |

7 × 6 |

= |

6 × 700 + 6 × 70 + 6 × 7 |

|

Add 777 6s |

|

Add 700 6s |

|

Add 70 6s |

|

Add 7 6s |

|

|

which gives 777 × 6 = 42 + 420 + 4200 = 4662. This is how it plays out on abacus rods:

Simply knowing the fundamental pattern that 6 × 7 = 42 gives us the ability to multiply 6 by any number involving only 7s and 0s (e.g., 7777 × 6, 70707 × 6, 77700077 × 6). For example, the multiplication 70707 × 6 looks like:

70707 × 6 = 70,000 × 6 + 0000 × 6 + 700 × 6 + 00 × 6 + 7 × 6 =

6 × 70,000 + 6 × 0 + 6 × 700 + 6 × 0 + 6 × 7 =

420000 + 0 + 4200 + 0 + 42 = 424242

Knowing that 4 × 3 is 12 will yield a similar result for multiplication by 4 of any number containing only 3s and 0s.

Thus the extent to which we can project our knowledge when we know a fundamental pattern is truly amazing. We may use this knowledge to literally multiply infinitely many more numbers. That is a lot of bang from a single pattern. In principle, if we know all of the fundamental patterns, we can project our knowledge even more (how far?). Is it possible to know all of the fundamental patterns?

The fundamental patterns are those that occur when we multiply the ten digits among themselves (e.g., 9 × 5, 4 × 7, 7 × 6). Since the number of such products is 100, we are yet again (for a third time) presented with the opportunity to make an operation alphabetic. If we learn and memorize these 100 fundamental patterns, it will be possible in principle to compute any product of the form (a single digit) × (any sized number).

The following tables show the 100 fundamental patterns in abacus rods (the tables reads as A × B):

Abacus Rod Multiplication Table

Abacus Rod Multiplication Table (Continued)

The power of this table can be shown in the calculation of 235 × 7:

|

235 × 7 |

= |

200 × 7 |

+ |

30 × 7 |

+ |

5 × 7 |

= |

7 × 200 + 7 × 30 + 7 × 5 |

|

Add 235 7s |

|

Add 200 7s |

|

Add 30 7s |

|

Add 5 7s |

|

|

Using these patterns and translating the situation to the proper location yields:

Thus 235 × 7 = 1645.

This method can be used to multiply a single-digit number by any sized number. To multiply a single digit by numbers with more than three digits (for instance, 5649 × 7), we simply add more rods to accommodate the larger place values and use the fundamental patterns given in the abacus rods table. This recipe using the abacus rods gives us a systematic method for handling all multiplications involving a single digit. Unfortunately, it is still too bulky for our tastes and needs to be further simplified.

As before with addition and subtraction, we can directly translate the abacus rod multiplication table into a table involving only HA script. The resulting table is probably the most well-known mathematical table of all and is called the multiplication table or times table:

Multiplication Table (or Times Table)

Armed with this table, we are able to multiply any number by a single digit in the manner of the previous examples, except now it can be done purely in script. The multiplication of 8432 × 8 shows how this is done:

8432 × 8 = 8000 × 8 + 400 × 8 + 30 × 8 + 2 × 8 =

8 × 8000 + 8 × 400 + 8 × 30 + 8 × 2

Translating the fundamental patterns to the proper location yields:

|

(tens and ones places) |

8 × 2 |

= |

16 |

|

(hundreds and tens places) |

8 × 30 |

= |

240 |

|

(thousands and hundreds places) |

8 × 400 |

|

3200 |

|

(ten thousands and thousands places) |

8 × 8000 |

|

64000 |

|

|

Adding these yields: |

|

67456 |

Thus 8432 × 8 = 67456.

Conclusion

Who would have guessed that tracking the total number of boxes shipped to a bookstore in a particular year or figuring out the total amount of money owed back on a signature loan of 36 months, would have anything to do with expressing timeless principles in nature? But it turns out that they do. Multiplication and its generalizations appear throughout the whole of mathematics and science—making their presence felt, even in many of the most esoteric attempts by scientists to describe symbolically how the world works (e.g., E = mc2 or Energy = [the mass] × [the speed of light] × [the speed of light]).7 In mathematics, by placing our fingers on a given problem, no matter how trite or pedestrian it apparently seems, we may end up measuring the pulse of the universe.

And it all begins here, with the type of ordinary problems we have discussed in this chapter. It is not unlike the physical scenario involving a tiny stream flowing out of the misty confines of a lake in northern Minnesota that eventually grows into a veritable torrent that becomes the world class Mississippi-Missouri River system ranking among the largest in the world.

Hyperbole aside, we are now midstream in our campaign to successfully grapple with multiplication. We have made significant strides in this chapter—acquiring the capacity, thanks to the Egyptians, to solve all of the originally stated problems (and infinitely more) by systematically sidestepping in some cases thousands of additions. Knowing we can do this gives the new operation of multiplication teeth as it means that we can work completely within the abbreviated form to more conveniently handle such problems. But our task is far from complete—much still needs to be simplified. This simplification is the focus of the next chapter.