12

Symbolic Illuminations

Man possesses what we might call symbolic initiative; that is, he can assign symbols to stand for objects or ideas, set up relationships between them, and operate with them on a conceptual level.

—Raymond Wilder, American mathematician, author of Evolution of Mathematical Concepts1

The mathematical student needs to use the telescope as well as the microscope, even if the latter instrument is the more important for those who desire to become experts along mathematical lines.

—George Abram Miller, American mathematician, educator, author of Historical Introduction to Mathematical Literature2

The naming of things, phenomena, and ideas by signs has literally helped us to create a “symbolic civilization” out of a vast and often confusing conceptual wilderness. Concepts in their rawest form, though potentially very powerful, can be wild, fluid, unruly even contradictory. Symbols have allowed us to establish some order, stability, and “light,” if you will, in this vast, untamed, and uncultivated world of ideas. In this chapter, we come full circle by once again reflecting specifically on how illuminating the process of naming with numbers/numerals can indeed be.

The Glow That Illumines

Language allows us to light up our world. With language we can refer, in significant and impactful ways, to things, actions, and so on, without physically pointing them out or even seeing them. The mere mention of the words “Las Vegas” or “Pacific Ocean” by someone on the radio can conjure up a host of images in the listener. The initial stimuli for these images are not the pictures of these places but rather the verbal words conveyed by the announcer’s voice. It is these sounds that are first processed by the brain to ultimately produce the images that come into the minds of the listener.

In a metaphorical sense, we can think of these responses to the audio words as the turning on of a set of mental lights. In fact, when neuroscientists study human cognition they image mental activity, in some cases, literally as lit up regions in the brain.3

Consider the following two maps of the United States. Notice how, for certain types of information, the naming in the second figure gives more context, depth, and structure (more light if you will) to the map than does the first figure without the names.

Map of the United States

Produced by the Cartographic Research Laboratory: The University of Alabama

Map of the United States with State Capitals

Produced by the Cartographic Research Laboratory: The University of Alabama

The map with names brings to the fore a host of new questions that would probably never arise from the nameless map, questions such as, which two state capitals are the closest together (Providence and Boston), or what is the southernmost state capital in the continental United States (Austin, Texas). This is the glow that illumines.4

You might think that taking the map and pumping it further with more information would bring in even more benefits. But if we do this indiscriminately, we run the risk of adding too much information, leading to a glare that obscures.

The use of language in adding understanding to a subject almost gives it a new dimension.

Quantitative Illumination

In what follows, when we speak of symbolic naming, we mean attaching a symbol or group of symbols (and the ideas they represent) to an object or idea in either a permanent or temporary fashion. This millennia old practice finds one of its fullest expressions when numbers are used in the naming. The ways in which numbers are used as names range from the mundane to the truly spectacular. In chapter 2, we have already discussed some ways that numbers are used as names. Before moving our discussion forward, we summarize these here:

• Measuring the size of a collection: If we name each member of a discrete collection of objects by using the ordered sequence of natural numbers {1, 2, 3, 4, . . .} then the last number used in the naming contains complete information about the size of that collection and thus measures it. This is a special type of number naming which we call counting.5

• Ordering collections: In performing a count of a set of objects, we are temporarily attaching number names to the individual members of that collection. Nothing then prevents us from actually using number names in a more permanent fashion to refer to those objects in place of their proper language names. This allows us to transfer the order present in a number sequence to the collections we name using them.

• This ordering can be precise, using the consecutive natural number sequence starting at the number one, or less exact, using a consecutive sequence of natural numbers not starting at one, or an ordered sequence of nonconsecutive natural numbers.

• Examples of using the consecutive natural number sequence include ordering the runners in a race according to how they finish, the pages in a book or the largest metropolitan areas in the United States according to their populations (e.g., largest metropolitan areas in the United States: (1) New York City, (2) Los Angeles, (3) Chicago).

• Labeling the south facing hotel rooms on the third floor with natural numbers or labeling houses on streets with numbered addresses give examples of using an ordered sequence of nonconsecutive natural numbers.

• Identification: If we want to uniquely identify millions of people then naming with numbers has advantages. With proper English language names uniqueness is lost as social conventions lead to many people having the same name, and there is no predictable way as to how such names are chosen.

• Numbers, on the other hand, are systematic and far outnumber any collection of people that we might care to classify. Examples of number names as unique identifiers include: social security numbers, student IDs, and state driver’s license numbers. Other examples of number names as identifiers (not necessary unique) include: credit card numbers, telephone numbers, and IP addresses.

The advantages of naming with numbers are extensive. In the next few sections, we take an interesting cross section of situations involving their use. As always, our hope is that a few insights can be gleaned along the way and that they can be used elsewhere by the reader as conceptual capital.

Navigation into Unknown Territory

If you happen to be totally disoriented or lost, sometimes all it takes is the recognition of a single familiar thing such as a landmark to change everything. The sight of this one thing can have an effect that is worth a thousandfold more than what might appear on the surface. It can allow you to place an entire landscape in context thus giving you the game-changing ability to successfully negotiate your way. Naming with numbers often gives us similar orientations when we are dealing with something unknown:

• Mileage of a vehicle: If you are considering the purchase of a seven-year-old vehicle, you care about the total number of miles the vehicle has been driven.

• What this number does is give you crucial orientation (in the same way that a landmark does for location) as to the history of a vehicle that you may have only seen once or never at all. While there are still many things about the vehicle that you won’t know from its odometer reading, knowing its mileage is a crucial component in whether most people would decide to purchase that vehicle or not.

• The age of a person: The simple knowledge of the quantity that describes the time a person has been alive can give you crucial insights about a person even though you may not have ever personally met them. For instance, if the person is a ninety-seven-year-old American in 2013, then you can immediately know that they probably have personal memories of the Great Depression, World War II, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Apollo missions, and Watergate but not of the Civil War, the assassinations of Lincoln, Garfield, or McKinley, or the sinking of the Titanic.

• Those who know their history have a map of events and their approximate dates in their head and these serve as a navigational map of sorts allowing them to place some of the major cultural experiences that a ninety-seven-year-old person may have experienced in the context of that map.

• Trip navigation: Navigating on a trip is significantly enhanced when signage and landmarks are available. However, many situations occur where neither signage nor landmarks are available. Ocean travel is one such scenario and numbers come to the rescue in the guise of longitude and latitude. Longitude and latitude assign a set of number coordinates to every location on the surface of the earth. For instance, the spot with number coordinates (latitude 0°, longitude 90° west) is located in the Pacific Ocean on the equator in the eastern portion of the Galapagos Islands archipelago.

• An important component in successful navigation is determining these coordinates—a task extraordinarily easy today but more difficult in the past. When Carpathia came to Titanic’s rescue, it could do so by being given the longitude and latitude coordinates of the beleaguered vessel.

• Numbers can help us in performing simple navigation while driving, even when road signs are not visible. If we know the distance between town A and town B is 200 miles and that our odometer shows that we have traveled 190 miles since leaving town A, then we know we are about 10 miles from town B regardless of whether or not road signs are visible or hidden by a fog or the whiteout conditions in a blizzard. This information can also tell us that our gas tank may be nearly empty even if the gauge isn’t working.

• Simple navigation with numbers occurs when we stay in a hotel. Knowing only the room number is sufficient enough information to find our way with the greatest of ease even though we are stepping off of the elevator onto a floor that we have never seen before in our lives.

More Sophisticated Counting: Measurement

Our ability to visually distinguish between size with precision and accuracy is, as we know, limited to very small numbers. That is, at a glance we can quickly distinguish between a group of two boxes and a group of three boxes. However we cannot on sight quickly distinguish between 998 boxes and 1,000 boxes. The ability to count changes everything.

What counting does is allow us to vastly extend our native abilities to distinguish even minute differences between very large sizes. Counting gives a warehouse manager the ability to conclude that during the night someone possibly stole two of her boxes even though her facility may be covered by a sea of the cardboard containers. She would never be able to tell this on sight alone, yet through counting (tally or order) she can. She could even distinguish the difference between a collection of 10,000 boxes and one with 9,998. Embezzlers beware!

The ability to count allows us to not only say that Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport had more passenger traffic than Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport in 2010 but to say by how much: 89,331,622 versus 66,774,738, respectively.6

Counting allows us to systematically see differences in sizes (large or small) with depth and structure. Visually we can only make crude comparisons for sizes larger than our subitizing ability. That is, we can certainly tell on sight that a group of 207 people is larger than a group of 42 people but we can’t say by exactly how much. The ability to count allows us to say by how much with the precise value of 165.

Using an analogy, without counting it’s almost as if we can’t distinguish individual faces except perhaps when they differ by gender or at least ten years of age but with counting we are able to actually recognize the complete range of faces as we naturally do.

Just as we obtain the ability to “light up” in great systematic detail the crude notions of “more people” or “a larger number of boxes” through the process of counting, we would also like to “light up” other crude notions in great systematic detail as well. Other such crude notions include:

1. Distance: Farther, shorter, longer, taller

• The distance from Chicago to Los Angeles is farther than the distance from New York to Washington, D.C.

• Kareem Abdul Jabbar is taller than Magic Johnson.

• A FedEx cargo van is longer than a Chevy Impala.

• Question: Exactly how much farther, shorter, taller, or longer?

2. Weight: Heavier, lighter

• The truck is heavier than the car.

• The book is lighter than the brick.

• Question: Exactly how much heavier or lighter?

3. Time: Longer, shorter

• The baseball game lasted longer than the tennis match.

• Alan Shepard’s space flight lasted for a shorter time than Yuri Gagarin’s.

• Question: Exactly how much longer or shorter?

4. Temperature: Colder, Hotter

• La Ronge, Saskatchewan, was colder than Bismarck, North Dakota, yesterday.

• The high in Phoenix was hotter than the high in Alice Springs, Australia.

• Question: Exactly how much colder or hotter?

5. Prices: More expensive

• A new Hyundai Sonata is more expensive than a new Hyundai Elantra.

• The silk shirt cost more than the cotton shirt.

• Question: Exactly how much more expensive?

To give structure in depth to the variations in these crude notions, we will need to develop some way to count them. In counting discrete objects such as people, books, and boxes, the criteria for being counted is simply existence as an individual entity. That is, if the object exists in the collection, it is assigned a number or is counted. Each object is a discrete packet all unto itself.

It is not as obvious, however, how to assign numbers to the notions of distance or weight or time since they don’t separate themselves into individual packets (i.e., they are not discrete). Can these things really be counted?

In spite of their not being discrete, the trick to devising a way to count these notions is to still define a fundamental discrete unit or quantum for them.

Consider the following line segments:

Segment A

Segment B

Segment B is clearly longer than segment A. However, if we want to state this in a more exact manner not just a crude one, then we need to devise some way to count these segments. We can count both by devising a standard unit by which we can measure them (this amounts to devising our “1”, if you will). Let’s define our standard to be the following:

One Token

We can use this unit to count both line segments. We do this by counting the number of copies of the fundamental unit it takes to equal the length of each segment:

Segment A with Tokens

Segment B with Tokens

The standard unit allows us to now say with more confidence that segment A is 5 tokens long and segment B is 8 tokens long.7 Thus the crude notion of segment B being longer than segment A can now be replaced with the more exact notion that segment B is 3 tokens longer than segment A.

If someone has a good feel for how long the fundamental unit is then they can have a feel for the lengths that correspond to both 8 tokens and 5 tokens as well as their difference of 3 tokens.

Using the tokens as we previously have quickly becomes a pain in the neck. Let’s rearrange them to a more convenient form by using hash marks to indicate each copy of a token. Doing so allows us to craft out a measuring device:

Placing the numerals under the hash marks yields:

Writing the ruled grid alone gives:

Now that the line itself is ruled, we can use it to measure length instead of using repeated copies of the individual tokens. Ruled lines like this are sometimes called number lines and find extensive use across a wide swath of mathematics.

Although we have used a discrete unit to count them, it is important to realize that lengths are still continuous magnitudes not discrete ones. What this means in essence is that when counting a discrete collection, such as a group of people, the size of the group must be one of the natural numbers {1, 2, 3, 4, . . . }. People come in whole units.

With lengths, far more variety exists. We could have situations such as those given below, where a whole number of fundamental units will not fit. The lengths of segments C and D are somewhere between 7 and 8 tokens. There is certainly nothing wrong with this—these scenarios are as valid as the scenarios above. But the quantities 7 or 8 are not exact enough to distinguish between the lengths of C and D or from other lengths that lie between 7 and 8. We need more values (accompanied by the corresponding numeral names). Those values of course are provided if we augment our whole numbers with fractions and more generally decimals.

In principle, any place on the line between 7 and 8 could represent the length of some segment. This corresponds to infinitely many more values—or what we call “a continuum of values.” With people, you either have 7 or 8 of them, nothing anywhere in between.

We can also count other crude notions such as “heavier” by choosing a fundamental unit or quantum for them as well. For instance, we might choose a certain type of brick as the standard for counting weight and then use a scale to count how many bricks it takes to balance another object. An object requiring 8 bricks to balance it would be said to weigh “8 bricks.” Such a system would allow us to give structure in depth and detail to the crude notion of weight just as the token allowed for length.

Making precise the crude notion of time by naming it with numbers is one of the most multilayered, fundamental systems of measurement we have. In June, when a meeting for a group of people, one-thousand strong, is scheduled at a hall in Boston for 9 p.m. on December 15, numbers guide their actions.

Without numbers, how will all of the people be able to unambiguously distinguish one night from the other or even certain portions of a given night from other portions? With numbers (namely, the date and the time of day) and the tools of a calendar and clock, these thousand people can with ease synchronize their actions and all show up at the same location at the same time. It doesn’t matter if it is dark outside, raining, or even half a year later, as long as they have the required tools, number naming allows them to successfully and collectively navigate through time.8

Calculation

One of the most spectacular demonstrations of the power in naming with numbers occurs when, in addition to utilizing their static properties as labels, we turn to their dynamical properties for change through combination with each other. When this happens, the ability of these ideas to transform into other ideas reaches a high art. This high art of transformation is demonstrated symbolically in the guise of performing calculations.

Quantitative ideas are less ambiguous than ideas such as “love” and “hate.” We can clearly tell that the collection of letters {A, B, C} has the property of three while the collection of letters {D, E, F, G, H, I} does not. This definitiveness allows us to create a much more precise and special way of communicating quantitatively about things, for in combining the unambiguous ideas of three objects and six objects, we don’t get gibberish nor varying interpretations which might be expected but instead get the equally unambiguous idea of nine objects.

And just as there are a multitude of different ways to symbolically describe reality by human languages, a myriad of different ways exist to symbolically describe this quantitative fact:

three plus six equals nine: English

: Coin Numerals

: Coin Numerals

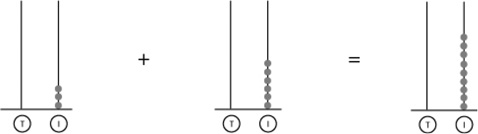

: Abacus Rods

: Abacus Rods

III + VI = IX: Roman Numerals

: Chinese Rod Numerals

: Chinese Rod Numerals

3 + 6 = 9: HA Numerals

The content of this fact comes from the way in which the ideas combine not from the symbolic expressions themselves. The symbols simply communicate how the ideas combine in abbreviated form.

This is not the end of the story, however, for the symbols play a far bigger role for us than simply abbreviating or representing an idea. The symbols provide us with a whole new way of looking at what is happening and also provide schematics which permit us to see crucial relationships unscreened.

This allows us to observe patterns in the symbols from which we can build sophisticated algorithms that enable us to obtain (calculate) answers to all sorts of scenarios in a much quicker fashion than we could physically working with the objects alone. We have seen how these patterns can be exploited to create the powerful algorithms we have today for the basic operations of arithmetic.

We can also view the ability to calculate as giving us yet another sophisticated way to “count.” Consider the case of the Begay family and their desire to predict how much they can expect to pay for gas on a 1,425-mile road trip. Can they “count” the dollar amount of gas they will use on the trip in the direct way?

Put another way, can they obtain the cost in the same manner that they can, say, count the number of people in a classroom—in a straightforward process of matching off? Unfortunately they can’t, as the cost in dollars doesn’t relate in a one-to-one fashion with the number of miles driven on the trip. That is, the family can’t simply count in a natural way the miles as they drive down the highway and then match these directly with the dollar cost for the gas. In fact, they can’t even see the gasoline once it has been pumped into the gas tank.

However, since the total gas cost depends on the components of distance traveled, the average gas price and the gas mileage, its value can be obtained through a calculation. What the calculation allows them to do is to bring these three components into conjunction to generate a numerical dollar value for the total quantity of gas used. Let’s assume that the average gas price is $3.00 per gallon and that the vehicle’s gas mileage is around 25 miles per gallon. From this information they can obtain what they need as follows:

The number of gallons they will need to purchase for the trip: The gallons come in 25 mile packets so to determine how many of these are needed to cover 1,425 miles, we need to calculate  . We use the symbolic algorithm for long division to do this:

. We use the symbolic algorithm for long division to do this:

Thus a total of 57 gallons are needed.

The cost to purchase 57 gallons at an average cost of $3.00 per gallon: The problem now reduces to the multiplication of 57 × 3. We do this using the standard U.S. multiplication algorithm:

And we see that the family should expect gas costs to be around $171.00.

The calculation gives a seamless way in which to transform one set of ideas into another set of ideas (“liquefying” them in a sense). Since every quantity or number represents an idea, we start with the ideas 1425, 3, and 25 and through well-defined algorithms (played out on HA number diagrams), we can smoothly and unambiguously transform these to the idea of 171 to obtain the estimated dollar cost of gas for the trip. Moreover, we are able to obtain this estimate on a piece of paper before the family ever embarks on the trip.

If we liken the ability to directly count a quantity to the ability in English to describe a concept or event by a single word, then we can metaphorically liken the “need to calculate” to find a quantity to the need in English to construct sentences to describe a concept. For example, no single English word allows us to describe the situation of “a group of ten people going to Pyramid Lake in Nevada for a picnic on a Sunday afternoon,” but this sequence of eighteen words does just fine in describing the event.

And for the record, sentences are capable of describing way more situations than single words can. For instance, the number of physical objects described by the word “house” numbers into the millions but the number of physical situations described by the statement, “the woman deposited money into the bank” easily numbers into the thousands of trillions (quadrillions). This statement is capable of describing all situations involving any living woman (of which there are billions) depositing any amount of money (numbering from one cent, or any other currency, on up) into any bank on the face of the earth (presently more than 7,000 FDIC banks are in operation in the United States alone).9

This means that we are not limited symbolically in using numbers to deal only with things that we can directly count. If we cannot directly count something (due to size, logistical difficulties, or inhospitable conditions), we may still be able to perform a calculation to gauge it (i.e., construct a “quantitative sentence” to measure it), and thus, calculation symbolically extends almost in an automatic way the things that we may subsume under the domain of number. Performing strings of calculations using elementary arithmetic gives perhaps the most accessible demonstration of the broad predictive power inherent in mathematics.

Calculations Are Symbolic Events

It can’t be emphasized enough that calculations just like direct counts are symbolic events, and in performing them we are speaking or writing about numerical interactions, not controlling them. Also, the calculations themselves, don’t directly alter the objects or events being described only what we can say about them, how we think about them, and ultimately what we may ourselves decide to do with them.

The numerals also exhibit the well-defined and reproducible properties of the things they describe, which mean that regardless of who is doing the calculations (if they do them correctly), they should come up with the same answer. This reproducibility is one of the hallmarks of calculation as well as mathematics in general.

Let’s look at a few examples to illustrate the discussion.

Symbolic simplifications don’t alter objects:

Consider the following coin collections:

A =  B =

B =  C =

C =

We can describe or label, respectively, the number of elements in each collection symbolically as:

3  4

4  4

4

Combining collections A and B together yields the collection:

A + B =

We can describe this symbolically as

3  + 4

+ 4  which simplifies to 7

which simplifies to 7  .

.

Since the objects are all of the same denomination we can simply write 3 + 4 = 7. It is important to remember that this is a symbolic simplification since physically seven distinct pennies are still present. The pennies have not been metallurgically combined to form a single object. They are simply represented as combining to a single object symbolically (Wilder’s “symbolic initiative”).

In the same manner, if we combine the collections A and C together we obtain the collection:

A + C =

We can describe this symbolically as 3  + 4

+ 4  .

.

This expression can’t be symbolically abbreviated any further (if we are identifying the coins by denominations). In both situations, we still physically have seven distinct objects. Whether we can simplify the descriptions symbolically or not does not alter these physical facts.

Conclusion

Naming with symbols often provides new information and insight into vague and confusing situations—giving structure and game-changing clarity where there was none. Since this is similar to what physical light can do when it is showered upon a darkened landscape, we have metaphorically referred to this ability in symbols as a type of illumination.

Number naming like language naming is deeply interwoven into the fabric of our society, and on most days we usually encounter numerous situations involving its use (note that even basic things such as simply changing TV stations, watching the speedometer in our vehicle, or setting the heating time on a microwave oven have components that use number names).

We now conclude by recapping explicitly some of the benefits obtained through naming with numbers:

1. Depth of expression: Instead of seeing only crude notions such as more, longer, larger, or heavier in situations that are infinitely varied, numbers allow us to give names in depth, to all of that variety. Moreover, the naming is systematic, understandable, and maneuverable.

2. Transformation of ideas: Perhaps the most potent aspect of naming with numbers is the ability to systematically and unambiguously transform ideas. These transformations allow us to connect information in obvious as well new and emergent ways not always easy to see at the start.

• This can be likened to the grammar in a language which gives us the ability to turn simple words (which are in and of themselves extraordinarily powerful) into a fuel that allows for the expression of the full range of life. Calculation in a sense allows us to almost symbolically liquefy phenomena—for ideas in symbolic and numerical form can, like fluids, naturally travel very far from their original sources while still retaining a powerful punch.

3. Reproducibility of result: Calculations and numerical representations have a well-defined, reproducible quality about them. Regardless of the time and the place or the symbols and methods employed, multiplication of the two natural numbers 52 and 86, as we have defined it, will always yield the value 4,472.

• If a package of 500 ordered but un-numbered pages is dispersed by a gust of wind, the recipient will have a difficult enough task just knowing if he has retrieved them all much more how to put the papers back into the correct order. However, if the pages are numbered, he can systematically reproduce the original ordering of the pages and as a consequence know whether or not he has retrieved all of them. All of this from simply labeling the pages with numbers. Philip Davis and Reuben Hersh actually define mathematics in terms of reproducibility by saying: “The study of mental objects with reproducible properties is called mathematics.”10

4. Predictive power: Naming with numbers gives us the ability to make predictions both through calculations and through direct representation.

• Calculation: Calculation gives us the ability to make predictions on the cost of a trip, the number of chairs in an auditorium, the amount of money we earn in a year given an hourly wage, the distance around the earth, the equal allotment of portions among a group of people, and so on and so on.

• Representation: Language representation itself gives predictive power, for if someone told us that Redwoods National Park has exceptionally large and tall trees—we visit it with expectations. We would be incredulous and felt lied to if upon arrival we found a treeless barren desert instead.

• We have similar expectations if we were to hear that the temperature outside is 120°F, and would be shocked, if upon stepping outside, found that it was snowing. We continually make decisions on what to wear based on simple numbers that give the estimated temperatures for a given day. This is the predictive power of representation.

• Representation of quantity is such a valuable thing on its own that if that was all that numerals were useful for they would still be worth their weight in gold.

5. Convenience of use with symbols: It is much easier to manipulate and handle symbols than it is to directly handle the things they represent. This gives a convenience of use which is shocking in its reach. From the combination of reasoning and the simple handling of symbols on a piece of paper in front of us, we acquire the capacity to answer questions of monumental importance—questions that would often simply be impossible to answer without.

All of this and more from just the elementary aspects of numeration alone! There are so many more stories yet to tell, still even in arithmetic, let alone the rest of mathematics, but the twilight of this text is upon us so these tales will have to wait for another day.