The first tourists arrived on the morning after the battle, Monday, 19 June 1815, as Captain Alexander Cavalié Mercer was sitting on a discarded French breastplate, having breakfast on the slope above Hougoumont with the gunners of G Troop. They stepped down from a carriage, holding perfumed handkerchiefs to their noses. ‘As they passed near us, it was amusing to see the horror with which they eyed our frightful figures,’ said Mercer.

Their breakfast was a hunk of veal found in a muddy ditch, cooked on the upturned lid of a camp kettle after having the mud scraped off with a sword but the stench came from the bodies. Mercer’s troop had killed so many French cuirassiers on the slope above Hougoumont with canister shot from their guns at point-blank range that their position was still marked some days later by the piles of bodies. Mercer and his troop were using their discarded cuirasses for camp chairs. There is a tourist plaque at the spot today.

It is just as well the visitors had not arrived an hour earlier or they would have seen the corpse of one of Mercer’s drivers called Crammond lying there too. ‘A more hideous sight cannot be imagined,’ said Mercer. ‘A cannon-shot had carried away the whole head except barely the visage, which still remained attached to the torn and bloody neck.’ He made sure he was buried before they had breakfast.

Mercer, who was from a military family in Hull and took the horrors of war in his stride, went for a stroll down to the old chateau but even he was appalled by what he found. Bodies were piled into the ditches:

The trees all about were most woefully cut and splintered both by cannon-shot and musketry. The courts of the Chateau presented a spectacle more terrible even than any I had yet seen. A large barn had been set on fire and the conflagration had spread to the offices and even to the main building. Here numbers both of French and English had perished in the flames and their blackened swollen remains lay scattered about in all directions. Amongst this heap of ruins and misery many poor devils yet remained alive and were sitting up endeavouring to bandage their wounds. Such a scene of horror, and one so sickening, was surely never witnessed.

The Lion Mound – Wellington was furious it ruined the Mont St Jean ridge. (Author)

There is probably no other British war site so charged with poignancy or such powerful legends as the chateau and farm at Hougoumont. Wellington said, ‘The success of the battle turned upon the closing of the gates at Hougoumont.’ If so, the future of Europe was also decided at this farm.

I was shocked by its dilapidated state when I first visited Hougoumont. There were holes in the roof, where the rain came in, there were great cracks in the walls and there was no trace of the famous north gates. They had been replaced by chain-link fencing with a big sign saying ‘Keep Out’. I discovered later the reason for the security was that thieves had stolen the six-foot-high crucifix from the chateau’s chapel. The cross with the agony of Christ had survived on the altar wall for 200 years still bearing the scorch marks of the fire on Christ’s feet that destroyed the house. It was viewed as a miracle that the fire that consumed the barns and the chateau had stopped at the feet of Christ. The theft was despicable, but it has since been recovered.

The farm’s condition was even worse when I visited Hougoumont again with Barry Sheerman, the Labour MP who took up the campaign to rescue Hougoumont in the House of Commons.*

Despite the modern fencing, there was still a heavy sadness that hung about the farmyard like a dark cloud, and as he walked through the north gate, Sheerman said: ‘I can feel the hairs standing up on the back of my neck.’ I knew what he meant. I had also had the ‘hairs-on-the-back-of-the-neck’ moment the first time I walked into the cobbled yard, where men had died in bitter no-quarter fighting at the gateway. I also felt the tingling sensation down my neck when I looked through a fireloop that had been hacked out of the brick garden walls by the defenders with their bayonets. Looking through the slit, I had the same view as Corporal James Graham when the French infantry attacked the walls. It was easy to imagine the din of battle, the smell of the powder, the yelling of the men and the screams of the dying and the fear that you would die too.

The defence of Hougoumont was one of the most heroic actions in British military history, as valiant as that more famous action at Rorke’s Drift in Africa in 1879 where 150 men held out against 4,000 Zulu warriors. Eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded for their action that day, and if VCs had existed in 1815 they would almost certainly have been awarded for the defence of Hougoumont.

The story of Hougoumont has been distilled into one heroic act of bravery – the closing of the north gate. Corporal Graham (later promoted to Lance Sergeant for his heroism) of the Coldstream Guards, an Irish farmer’s boy from County Monaghan, became known as the ‘Bravest Man in England’ for his deeds. However, I discovered when I began to dig deeper into the story of the siege that the truth is far more complicated than that. Hougoumont’s walls were breached not once but at least three times, and possibly more, and there were many heroes.

Around 10 o’clock on the morning of the battle, the Duke of Wellington rode with his staff down the slope to the chateau by a dense beech wood to inspect the defences of Hougoumont, because he knew it was of crucial importance to holding his line. He had put Lieutenant Colonel James Macdonell of the Coldstream Guards, the six-foot-tall son of a Scottish highland clan chief, in charge of the defence of Hougoumont.

There had already been one skirmish for the farm before Wellington arrived for a tour of inspection with his staff officers – a party of French cavalry tried to seize it the night before but had been beaten off. Overnight, Macdonell had ordered his men to turn the old farm into a fortress. They had spent the night barricading three of the entrances, hacking out the fireloops in the walls, smashing out roof tiles from the roofs of the barns and the farm buildings so they could fire through them at the French they could see massing across the rolling fields of corn to the south.

There had been a chateau at Goumont for five centuries, before Macdonell and his men arrived in the night. The owner of the chateau, Chevalier de Louville, was 86 and living in Nivelles but the tenant farmer, Antoine Dumoncea, had fled. So had the gardener’s wife, but the gardener, Guillaume van Cutsem, had delayed and was found nervously sheltering in the farm when the Coldstream Guards arrived at nightfall.

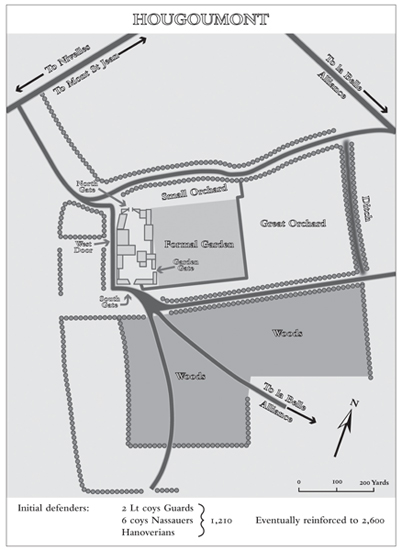

The farm buildings and the chateau formed three sides of a square with high walls facing the French. A great barn ran down the west side and a towering gatehouse to the south, with two windows above the huge dark-blue gates to provide elevated shooting positions, and a window in a garret above that. The gatehouse was flanked on the south side by a shed with a steep pantiled roof and on the other side by the gardener’s house, with another stable and office building. They were enclosed by an impressive garden wall of red brick, about 8ft high, running along the whole south side of the farm, which shielded the farm from a direct French attack. Behind this wall was a small cottage garden and a formal garden laid out in the Dutch parterre style with an orchard on the north side. Macdonell’s men had laid timbers along the base of the wall to provide fire steps so they could fire muskets over the wall at the attackers.

Inside the south gatehouse was an inner courtyard and a door leading into the main cobbled farmyard, with the stables, a circular dovecot and a well for fresh water. The two-storey chateau had a picturesque tower containing a staircase topped by a weather vane. The small family chapel with a spire was attached to the chateau on the south side and a farmer’s house attached at the east side with a gate into the formal garden. Three of the gateways had been barricaded with heavy timbers, old carts, slabs of stone – anything the men could lay their hands on. Only the north gate had been left open, to enable the farm’s defenders to be resupplied with ammunition and reinforcements during the long hard day ahead. The gate opened into a lane that had been cut down by centuries of cart traffic between two high banks with trees on either side. It was called the ‘hollow way’ and ran up to the ridge where Wellington’s main forces were lined up. It was to prove a vital lifeline.

Hougoumont’s defences looked formidable. Macdonell was given four light companies of Maitland’s 1st Brigade and Byng’s 2nd Brigade of the 1st British Guards Division. The two companies of the 1st Brigade under the command of 30-year-old Lieutenant Colonel Lord Saltoun occupied the front edge of the orchard. The farm and chateau were occupied by the light company of the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Wyndham. The garden and ground around the farm was defended by the light company of the 2nd under Lieutenant Colonel Charles Dashwood. They reinforced some crack German troops armed with rifles, including elite Hanoverian Jägers (hunters). Macdonell had deployed them through the orchard, the buildings, the lofts and the wood. But Baron Friedrich von Müffling, the Duke’s Prussian liaison officer, was still sceptical. Müffling asked Wellington whether he really expected to hold Hougoumont with 1,500 men. ‘Ah,’ said the Duke. ‘You don’t know Macdonell.’

That was disingenuous. Macdonell was undoubtedly a formidable commander. He was the third son of the Scottish clan chief, Duncan Macdonell, and was born at the clan seat at Glengarry in Inverness. The MacDonell clan – a branch of the Donalds – are proud Highlanders who can trace their roots back to the ancient Picts. But the truth is Wellington committed more than 2,600 men to the defence of Hougoumont and some estimates put the total deployment at over 7,500 men, if you include Byng’s men alongside Maitland’s guards on the slopes behind Hougoumont.

James Macdonell joined the 78th Highlanders Regiment as a lieutenant in 1794 at the age of 13, when it was routine for young boys to become soldiers. He joined the Coldstream Guards in 1811 and fought in the Peninsular War. He was 34 when he arrived at Hougoumont. There is a portrait of Macdonell in the National Portrait Gallery, which shows him in late middle age wearing the scarlet uniform of a general (which he later became), with a dress sword; he has reddish side-whiskers and he stares out of the portrait with a steady gaze that looks as though he would brook no dissent.

Wellington ordered Macdonell to defend Hougoumont to the ‘greatest extremity’, by which he meant ‘to the death’. If it fell, Napoleon could turn Wellington’s right flank. However, it remains unclear whether Napoleon saw its strategic significance. In his general order for the battle issued at 11 a.m., Napoleon gave only a passing reference to Hougoumont, saying the 2nd Corps ‘was to support the movement of the 1 Corps covering the left of the Hougoumont wood’. The main attack was to be directed at Wellington’s centre on Mont St Jean. This has given the impression that the attack on Hougoumont was a diversion aimed at drawing men away from Wellington’s centre. If so, it backfired badly, as more of Napoleon’s forces were drawn into the attack on Hougoumont, while Wellington saw that it held with a minimum force. More than 12,000 French troops were committed to the siege and over 6,000 French and allied men were killed or injured around its walls.

Marshal Honoré Reille, commander of the 2nd Corps, entrusted Napoleon’s youngest brother, Jérôme Bonaparte, head of the Sixth Division, with leading the siege of Hougoumont, reinforced by Foy’s 9th, the 5th under Guilleminot and Joseph Bachelu, and Kellerman’s cavalry. Late in the day – far too late – Napoleon pushed forward artillery to pound the walls and buildings with howitzers, which set the barns on fire.

There is still a dispute about when the Battle of Waterloo started – Wellington said ‘about ten o’clock’; Lieutenant Colonel G. Gawler said an officer near him pulled out a watch and noted,‘twenty past 11 o’clock’ – but there is no dispute that the first shots were fired over Hougoumont and that they came from allied guns.

Wellington, vigilant on the ridge, saw Jérôme’s troops advancing towards the wood, and asked Uxbridge to bring Major Robert Bull’s troop of howitzers to bear on them. The Royal Horse Artillery troops were intended to be mobile and fast. John Lees, the young wagon driver from Oldham, and his comrades in Major Bull’s I Troop had been ordered from their bivouac at 8 a.m. on the morning of the battle and were posted to the left of the road from Waterloo to Charleroi, alongside Lieutenant Colonel William Ponsonby’s Heavy Brigade. They had been there for an hour when Bull received the fresh orders from the Earl of Uxbridge to move. Lees and the other drivers urged their horses across the ridge to the right of Wellington’s lines and the slopes above Hougoumont. Wellington rode across the slope to Bull and pointed out Jérôme’s men as they were advancing through the wood about 1,000yds away. The Duke said he wanted Bull to dislodge them. It was a tricky operation. Bull’s six howitzers had to fire shells over the heads of his own troops to explode directly over the French. If they fell short, or were off target, it could be a disaster and sow mayhem among the defenders. The shells, spherical cases carrying metal balls with lit fuses, had been designed by a lieutenant in the British Army artillery called Henry Shrapnel and were still regarded as novel – the French did not use them. The first Shrapnel shell looped over Hougoumont and exploded among the French infantry, killing seventeen men in one blast of red-hot metal. The devastating impact on Jérôme’s men was witnessed by Major William Norman Ramsay, who had been given command of H Troop despite incurring Wellington’s anger for insubordination at Vitoria. His troop was posted to the left of I Troop and he told Bull that ‘the shells opened a perfect lane through them …’ Ramsay was later killed by a musket ball, and buried on the field in a lull in the fighting by his friend Sir Augustus Frazer, the commander of the Royal Horse Artillery.*

Bull’s battery of howitzers was repeatedly overrun by French cavalry in the afternoon and had to retreat inside the nearest hollow squares of infantry. It was also fired on by French artillery, killing men and horses, including the second captain Robert Cairnes.1 Bull was injured and lost a lot of blood, but after having ‘my arm tied up’ returned to carry on the battle.

Some of the drivers took their horses and carts into the hollow way on the ridge to escape the worst of the French artillery bombardments, and it is likely Lees would have joined them. But for the rest of the battle Lees was in the thick of the fighting, seeing men and horses killed all around him. However, after 5 p.m., through loss of men, horses and ‘the disabled condition of the guns (through incessant firing) …’ Bull’s I Troop was forced to retire.

The Duke later praised Bull’s dexterity with the Shrapnel shells but Jérôme’s men pressed on their attacks. The crackle of muskets became a cacophony of fire as wave after wave of Jérôme’s infantry burst through the woods, to be cut down under a hail of rifle and musket balls. ‘Soon we had our feet bathed in blood,’ said Lerreguy de Civrieux, aged 19, a sergeant major. ‘In less than half an hour our ranks were reduced by more than half. Each stoically awaited death or horrible wounds. We were covered in splashes of blood …’ The dead included Brigadier General Bauduin but Jérôme pressed on with the attacks, even though his men were being cut down.

Prince Jérôme may have felt he had something to prove to his older brother. Ten years earlier, when he was only 19 and in America, Jérôme enraged Napoleon by falling in love and marrying an American heiress on Christmas Eve 1803. Eighteen-year-old Betsy Patterson was the beautiful, dark-haired daughter of a Baltimore businessman, but she was regarded as unsuitable by Napoleon. He had wanted a European power-match for his brother and ordered the pope to annul the marriage; when the pontiff failed to do so, the emperor did so himself by Imperial decree in March 1805. Jérôme and Betsy sailed to Europe to make an appeal to the emperor; they landed in Portugal and Jérôme went overland to plead with his brother, while his wife went by ship to Amsterdam to travel to Paris, but Napoleon refused to allow her entry to France. Betsy, however, was pregnant, and was forced to sail to England; she gave birth to Jérôme Bonaparte II at 95 Camberwell Grove in leafy South London. The Georgian house is still there in a tree-lined street, but the area, near the Elephant and Castle, is now part of the urban inner city. After the birth of Jérôme II, Prince Jérôme’s son and heir, Betsy returned to her family in America with the baby and founded an unlikely American Bonaparte dynasty. The infant Jérôme II – known as ‘Bo’ – was brought up by his rich mother in Baltimore and married Susan May Williams, daughter of a fabulously wealthy Baltimore rail magnate. They were given the landmark Montrose Mansion in Maryland as a wedding present and had two sons, firmly establishing the Bonaparte line in the US. Meanwhile, Jérôme meekly bowed to the emperor’s wishes. Napoleon married his youngest brother off to a German princess, Catherina of Wurttemberg, and made Jérôme King of Westphalia, a made-up title for a made-up country that only lasted until 1813.

Now at 30, Jérôme (no longer a king, but a mere prince) was clearly determined to show his brother he could take Hougoumont. Jérôme threw more men forward without much of a plan.

Lieutenant Puvis from the 93rd de ligne was told, ‘We are going to attack the English lines ‘a la baionnette’.’ Bayonets were useless against the walls, but still they went forward and quickly found themselves pinned down behind a hedge that Ensign George Standen of the Light Company of the 3rd Foot Guards described as a ‘real bullfincher’. It ran parallel to the garden wall, and gave some protection to the attackers hiding behind it but when they charged round it, they were caught in the deadly crossfire from the fireloops in the garden walls. The strip of open land between the hedge and the wall became a killing zone, piled high with the French dead: ‘We tried to get through this hedge in vain. We suffered enormous casualties; the lieutenant of my company was killed closed to me. A ball struck the visor of my shako and knocked me onto my backside …’

A cloud of skirmishers pushed through the cornfield and the wood, forcing a Nassau battalion and the Jägers through the wood to the rear of the chateau until a counter-charge by Macdonell forced the French back once more. General Guilleminot, chef de l’Etat to Jérôme, told the Coldstream Guards officer Sir Alex Woodford, when they met in Corfu years later, that he advised Jérôme on the first attack but was against Jérôme’s other attacks: ‘It always struck me the subsequent attacks were feeble,’ said Woodford.2

After nearly two hours of largely futile slaughter, the charismatic French Colonel Amédée-Louis Despans, the Marquis de Cubières, who already had one arm in a sling from an injury at Quatre Bras, tried a different approach, and nearly succeeded.

After 1 p.m., as the battle for the farm raged, a cart of ammunition was lashed under heavy fire through the north gate by a young wagon driver, Corporal Joseph Brewer. The men had only time to fill their pouches when cannon fire ‘suddenly burst upon them mingled with the shouts of a column rushing on to a fresh attack’. Captain Seymour, Lord Uxbridge’s ADC was inadvertently responsible for this show of valour by Brewer. He recalled:

Late in the day I was called by some officers of the 3rd Guards defending Hougoumont to use my best endeavours to send them musket ammunition. Soon afterwards I fell in with a private of the Wagon Train in charge of a tumbril on the crest of the position. I merely pointed out to him where he was wanted when he gallantly started his horses and drove straight down the hill to the farm to the gate of which I saw him arrive. He must have lost his horses as there was a severe fire kept on him. I feel convinced to that man’s service the Guards owe their ammunition.

However, it may have given Cubières the clue to the chateau’s Achilles heel: the north gate. He realised that the north gate was not barricaded and was kept open to admit the supplies of ammunition; he put together a party to attack it.

Cubières, who had fought in Spain, picked a burly veteran of the Spanish campaign, Lieutenant Bonnet, to lead it and some axe-wielding pioneers to back him up. British accounts say he was called Legros, which literally translated means ‘the big’. That certainly describes Bonnet. Around 100 men of the Coldstream Guards were outside the high barn walls on the west side of the farm, including Private Clay of the 3rd Foot Guards, who had tested his musket in the damp dawn. He was kneeling behind a hedge, and poked the muzzle through it to fire at the attackers. Clay and his comrades soon had musket balls zipping around their bodies. Ensign Charles Short of the Coldstream Guards said:

We were ordered to lie down on the road, the musket shots flying over us like peas – an officer next to me was hit in the cap, but not hurt, as it went through; another next to him was hit also, on the plate of the cap, but it went through also without hurting him. Two sergeants that lay near me were hit in the knapsacks, and were not hurt besides other shots passing as near as possible.

The Guards were forced back into the hollow way by the north corner of the farm. Ensign Standen, a cap in one hand and a sword in the other, ordered some of the men including Clay and Private Robert Gann, a seasoned soldier over 40 years of age, to cover the retreat by attacking the French. Clay and Gann dropped behind the cover of a circular haystack to fire on the attackers but the French set fire to the hay. Clay and Gann were forced back by the heat from the flames, the smoke, and the heavy musket fire to seek whatever cover they could. Cubières spurred his horse towards the gates, and rallied his men with a drummer boy beating out the pas de charge to capture the north gate.

As Cubières reached the farm track, he was pulled from his horse by Sergeant Ralph Fraser, a veteran who had fought through the Peninsular campaign, wielding a halberd, an axe on a long pole. Cubières fell to the ground, just below the wall of the west barn. He was about to be shot by the defenders inside the barn, but a Guards officer inside the barn knocked down the rifles of his men to stop the injured Cubières being shot, because he had shown such courage. Lieutenant Colonel Sir Alexander Woodford of the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards later said Cubières made a fuss of it every time they met.3 But there was to be little quarter given after that.

Mackinnon, the historian of the Coldstream Guards, who was posted in the farm’s orchard says the ‘enemy compelled the few men who remained outside to withdraw into the chateau by the rear gate.’ Ensign Standen, Sergeant Fraser and the remaining Third Guards took a lull in the firing to run for their lives inside the north gates, which were slammed shut as soon as they were inside. The defenders rammed ladders, posts, barrows, or whatever was nearest to hand, against the gates to barricade them. But Clay and Gann were cut off from their retreating friends and were stranded, keeping their heads down, outside the farm.

Bonnet grabbed an axe from one of the pioneers and smashed at the lock on the gate* while some powerful sapeurs threw themselves at the gates and began hacking at the panels of the doors. Bonnet ‘struck with mighty blows the side opening at this entry, threw it down, and penetrated into the courtyard …’ The French raiders poured into the cobbled yard, which was puddled with the overnight rain. Bonnet and his men were caught in a hail of musket balls fired into them from the farmer’s house and the barns, and the roofs of the farm buildings. Ensign Standen said: ‘We flew to the parlour, opened the windows and drove them out, leaving an officer and some men dead within the wall.’ A French account said: ‘Bonnet and his men were shot down at point-blank range from an elevated platform. All found death there …’4 The firing died with the last French attacker. Bonnet was left lying dead on the cobbles, still holding his axe. Outside, there were more attackers but they hesitated, waiting for reinforcements.

Macdonell, who was across the yard by the gate into the north garden, realised the farm would fall unless the north gates were slammed shut and barricaded again. Macdonell dashed across the yard, shouting at three Coldstream Guards officers to join him in closing the gates. Captain Harry Wyndham, Ensign James Hervey and Ensign Henry Gooch raced across the yard to shut the gates with Macdonnel, and were joined by Corporal James Graham and his brother Joe with four more guardsmen – Sergeants Fraser, McGregor, Joseph Aston and Private Joseph Lester. At that moment, Clay, 20, and Gann, 41, made a run for it. Clay grabbed a discarded musket as he ran – it was still warm from firing – because his own had failed, and scrambled inside the gates with Gann just as they were heaved shut again.

Clay later noted in his pay book, which he used for his journal:

On entering the court-yard, I saw the doors or rather gates were riddled with shot-holes, and it was also very wet and dirty; in its entrance lay many dead bodies of the enemy; one I particularly noticed which appeared to have been a French officer, but they were scarcely distinguishable, being to all appearance as though they had been very much trodden upon, and covered with mud.

On gaining the interior, I saw Lieutenant Colonel Macdonell carrying a large piece of wood or trunk of a tree in his arms (one of his cheeks marked with blood, his charger lay bleeding within a short distance) with which he was hastening to secure the gates against the renewed attack of the enemy which was most vigorously repulsed.

‘Occupy the ruined walls’ was Wellington’s order, as Hougoumont chateau was engulfed in flames. Corporal Graham only deserted them to rescue his brother from the flames, which made him a national hero.

Macdonell and his party threw their weight against heavy doors forcing them shut. Immediately they piled stone slabs, broken beams and the remains of broken wagons and farm implements against the gates.

Outside, a French Grenadier was lifted to the top of the wall on the shoulders of the French attackers with a musket. He aimed it at Captain Wyndham, who shouted to Graham: ‘Do you see that fellow?’ Graham snatched up his musket, took aim and shot the Frenchman dead. No others dared to follow. The French attackers were driven from the gates along the hollow way by four companies of Coldstream Guards under Colonel Alexander Woodford.

Inside the farm, Clay, black-faced from biting the ends off countless musket cartridges, was ordered with others into an upper room of the chateau by Ensign Gooch to prepare for the next attack. They did not have long to wait. They began firing down on the skirmishers through the windows but the French brought up some guns and fired howitzer shells at the building. Suddenly, flames leapt across the roof of the barn. ‘Our officer placed himself at the entrance of the room and would not allow anyone to leave his post until our position became hopeless and too perilous to remain,’ said Clay.

Burning beams and rafters crashed down, sending red-hot embers flying among the men, as roundshot and flaming missiles smashed into the buildings. Flames burst through the roof and a pall of black smoke filled the air over Hougoumont.

Up on the ridge, the flames and smoke over Hougoumont were immediately spotted by the hawk-eyed Wellington through his telescope. He scribbled a note to Macdonell:

I see that the fire has communicated from the Hay Stack to the Roof of the Chateau. You must however still keep your men in those parts to which the fire does not reach. Take care that no men are lost by the falling-in of the Roof or floors. After they have both fallen in, occupy the ruined walls inside of the Garden; particularly if it should be possible for the enemy to pass through the Embers in the inside of the house.*

Major Macready, of Halkett’s brigade, saw the fire:

Hougoumont and its wood sent up a broad flame through the dark masses of smoke that overhung the field; beneath this cloud the French were indistinctly visible. Here a waving mass of long red feathers could be seen; there, gleams as from a sheet of steel showed that the cuirassiers were moving; 400 cannon were belching forth fire and death on every side; the roaring and shouting were indistinguishably commixed – together they gave me an idea of a labouring volcano.

Manning the garden wall facing the wood at Hougoumont, Corporal Graham asked Macdonell for permission to fall out. Graham had been in the Coldstream Guards for three years and Macdonell knew he did not lack courage; he expressed surprise at his request. Graham said he wanted to save his brother, Joe, who had been injured and was in the blazing barn. James immediately won Macdonell’s approval and ran to his brother, dragged him clear and left him in a ditch, to protect him from the shelling, but returned to the walls of the besieged farm. Others who were injured sought refuge in the small chapel, which after the battle was all that remained of the chateau. Many injured men who had been dragged into the barn were not so lucky. Woodford said: ‘The heat and smoke of the conflagration were very difficult to bear. Several men were burnt as neither Colonel Macdonell nor myself could penetrate the stables where the wounded had been carried.’5 Ensign Standen said: ‘During the confusion, three or four officers’ horses rushed out into the yard from the barn and in a minute or two rushed back into the flames and were burnt.’

The siege was only lifted after 7 p.m., when the allied infantry charged past Hougoumont in pursuit of the retreating Imperial Guard. Captain H.W. Powell of the 1st Foot Guards noted in his journal:

Lord Saltoun … holloaed out, ‘Now’s the time, my boys.’ Immediately the brigade sprang forward. La Garde turned and gave us little opportunity of trying the steel. We charged down the hill till we had passed the end of the orchard of Hougoumont …

It was only then that the defenders of Hougoumont knew, after over eight hours under siege, they had won.

Ensign Short of the Coldstream Guards, who had survived rain, gin and the siege, wrote a boyish summary of the battle to his mother from Nivelles that Monday:

Dear Mother … I never saw such luck as we had. The Brigade Major was wounded by a cannon ball, which killed his horse and broke his arm; and General Byng was wounded slightly while standing opposite me about five paces. General Byng did not leave the field. Lord Wellington with his Ball dress was very active indeed, as well as Lord Uxbridge and the Prince of Orange, both severely wounded, the former having lost his leg and the latter being hit in the body. General Cooke, commanding our Division, lost his arm. The battle kept up all day in this wood where our Brigade was stationed. The farm-house was set on fire by shells, however we kept possession of it. The Cavalry came on about five o’clock, and attacked the rest of the line, when the Horse Guards and the other regiments behaved most gallantly. The French charged our hollow squares and were repulsed several times – the Imperial Guards with Napoleon at their head charged the 1st Guards, and the number of killed and wounded is extraordinary – they lie as thick as possible, one on top of the other. They were repulsed in every attack, and about seven o’clock the whole French army made a general attack for their last effort, and we should have had very hard work to repulse them – when 25,000 Prussians came on, and we drove them like chaff before the wind, 20,000 getting into the midst of them played the Devil with them, and they took to flight in the greatest possible hurry. The baggage of Bonaparte was taken by the Prussians, and the last report that has been heard of the French says, that they have re-passed the frontier and gone by Charleroi hard pressed by the Prussians. The French say that this battle beats Leipsic [sic] hollow in the number of killed and wounded. Our Division suffered exceedingly. We are to follow on Thursday. Today we bivouac at Nivelles. Lord Wellington has thanked our Division through General Byng, and says, ‘that he never saw such gallant conduct in his life’.

Bull’s howitzer troop stayed close to the battlefield until 3 p.m. on Monday, when they were ordered to move. John Lees whipped his horses in the direction of Paris, but the young wagon driver’s role in the turbulent history of his times was not over. He and Byng would be involved in one of the worst atrocities that Britain (see Chapter Ten) has witnessed.

The story of the closing of the gates at Hougoumont captured the imagination of Georgian Britain. It was told as a tale of uniquely British heroism (though German troops were there) and Wellington helped to consolidate that legend, saying over one of his suppers at Deal Castle in 1840: ‘You may depend on it – no troops could have held Hougoumont but British, and only the best of them.’ Walter Scott was inspired to some bad verse:

Yes – Agincourt may be forgot

And Cressy be an unknown spot

And Blenheim’s name be new;

But still in story and in song

For many an aged remember’d long,

Shall live the towers of Hugomont

And field of Waterloo.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle drew on the heroic wagon driver Brewer, who delivered ammunition to Hougoumont under fire, for a short story, A Straggler of ’15, although his name was changed to Brewster.

I discovered that the true story of Hougoumont is surrounded by myths. The most persistent myth is that the walls were breached only once. Mackinnon said the French smashed their way through the north gate twice in his official history of the Coldstream Guards in 1833:

The gate was then forced. At this critical moment, Macdonell rushed to the spot with the officers and men nearest at hand and not only expelled the assailants, but reclosed the gate. The enemy from their overwhelming numbers again entered the yard, when the Guards retired to the house and kept up from the windows such a destructive fire, that the French were driven out and the gate once more was closed …6

Gareth Glover, one of the outstanding British experts on Waterloo, told me he believed Mackinnon was confused because he was not in the farmyard at the crucial moment: ‘I checked a number of eyewitness accounts, but no one seems to agree with his confused version. The closing of the gate was so famous for its success – this does not make sense if it failed and they broke in again just after!’ He believes Mackinnon confused his account with a second break-in through a small gate by the side of the great barn on the west side of the farm. This was described by Lieutenant General Woodford of the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards. He said: ‘Some few of the enemy penetrated into the yard from the lane on the West, but were speedily driven out, or dispatched.’ This is supported by the French versions, which say as many as seventy men tried to get in through this small gate but were repulsed.

Private Clay says the French broke in a third time, through the doors of the great gate house on the south side (which he called the upper gates):

The enemy’s artillery having forced the upper gates, a party of them rushed in who were as quickly driven back, no one being left inside but a drummer boy without his drum, whom I lodged in a stable or outhouse …

A round shot burst them open; stumps intended for firewood laying within were speedily scattered in all directions, the enemy not having succeeded in gaining an entry.

The gates were again secured although much shattered.

Clay’s account led to the most famous myth that when the north gate was breached, the only one of the French attackers left alive was the little drummer boy. Clay makes it clear the boy was stranded in the subsequent attack.

A patriotic cleric, the Reverend John Norcross, the curate of Framlingham in Suffolk, was so moved by the stories of heroism at Waterloo that on 19 July 1815, one month after the battle, he wrote to Wellington, who was then in Paris, offering a pension to the man of the Duke’s choice who he believed had showed the greatest bravery. Inevitably, the man chosen became known as the ‘Bravest Man in England’.

Framlington was one of the richest livings in the country and Norcross, aged 53, offered an annuity to be called the ‘Wellington Pension’ and paid on Waterloo Day, 18 June, every year for the rest of the curate’s life. The current incumbent of the Framlington curacy and his wife showed me a copy of the letter. Reverend Norcross wrote:

If your Grace will do me the honour to nominate any one of my brave countrymen who have fought under your Grace’s banners in the late tremendous but glorious conflict – I shall have great pleasure in settling upon him for the continuance of my life an annuity of £10 which I humbly request your Grace will permit to be entitled the Wellington Pension.

Norcross said on receipt of the Duke’s recommendation, the first payment would be immediately advanced and in future, with his Grace’s approbation, paid on each anniversary of the ‘memorable’ 18 June:

I will not add more than that, with the exalted sentiments which I entertain of your Grace’s transcendent merits and appreciating as I do your splendid and unparalleled achievements, were means commensurate to my inclinations, I would cheerfully centuple the sum I mentioned.

As Norcross hinted, £10 a year – 3s a week – was hardly a prince’s ransom even in 1815, but it was a handy sum for a soldier reduced to charity after the war.

Wellington replied in a letter dated Paris, 31 July, promising at the earliest opportunity to make the Reverend Norcross ‘acquainted with the name of the soldier, whom, upon enquiry, I shall find most deserving of your bounty’. Wellington added that it was the same ‘patriotic spirit’ which had induced Norcross to make his financial sacrifice and which so generally prevailed in England that had given so much encouragement to the ‘discipline and courage’ of his men. It was ‘to this spirit that we owe the advantages we have acquired in the field and I beg leave to return you the best thanks in the name of the brave officers and soldiers whom I have had the happiness of commanding.’

On 24 August 1815, Wellington again wrote to Reverend Norcross at Framlingham Rectory from Paris:

Sir, having made enquiries respecting the soldier to be recommended to you in consequence of your letter of 19th July, to which I wrote an answer on 31st July, I now have leave to recommend to you Lance Sergeant Graham of the Coldstream Regiment of Guards. I have leave to return to you my thanks for your patriotism and your benevolence towards those which have so well deserved the approbation of their country.

Wellington passed Norcross’s letter on to Sir John Byng with a request to choose a man from the 2nd Brigade of Guards, which had so highly distinguished itself in the defence of Hougoumont. According to Captain William Siborne, who interviewed Sergeant Graham, it was Byng who picked him, because of the way he rescued his brother from the flames. It was the kind of selfless heroism and human interest story that was certain to capture the hearts of the public in Regency Britain.

John Booth, in his history of Waterloo written only the year after the battle, claimed Norcross had asked for a non-commissioned officer to receive his pension, but Norcross’s letter makes no mention of that. There is another myth that Norcross left £500 in his will to Macdonell and the officer split the money with Graham. I have obtained a copy of Norcross’s will from 1837 and while he left money to his wife and a number of others, there is no mention in his will of Macdonell, Graham or any others connected with Waterloo.

The Irishman with the curly black hair was given a special bravery medal by his fellow sergeants in addition to his Waterloo Medal. In his Waterloo Despatch, Wellington singled out the saving of Hougoumont for special praise:

At about ten o’clock he [Napoleon] commenced a furious attack upon our post at Hougoumont. I had occupied that post with a detachment from General Byng’s brigade of Guards, which was in position in its rear; and it was for some time under the command of Lieut. Colonel Macdonell, and afterwards of Colonel Home; and I am happy to add that it was maintained throughout the day with the utmost gallantry by these brave troops, notwithstanding the repeated efforts of large bodies of the enemy to obtain possession of it.7

Macdonell, who was injured and had to hand over to Home late in the day, was awarded a knighthood by the Prince Regent and made a Knight of Maria Theresa, an Austrian gallantry award that carried a pension. He rose to become a major general and retired to his estates in 1830, where he died in 1859. Sergeant Fraser, who unhorsed Cubières, was discharged two years after Waterloo ‘in consequence of long service and being worn out’; he was lucky – he found a post as a Bedesman at Westminster Abbey and died in 1862, aged 80.

Matthew Clay endured terrible poverty in old age. He married his wife Johanna at Stoke Dameral in Devon in 1823; they moved to Bedfordshire and had twelve children, though – in common with mortality rates at the time – only three survived. He spent eleven years after Waterloo as a drill sergeant and after being discharged from the Guards with a pension of 1s 8d, he supplemented his income by serving for another twenty years as a sergeant in the Bedfordshire militia. He moved to his birthplace, Blidworth in the Sherwood Forest, in old age. His wife Johanna took in laundry, but she was struck by paralysis and Clay was so poor that he had to sell furniture and other possessions to keep them alive and pay the rent.

A family member, Christine Dabbs Clay, who researched her ancestor, said:

Matthew struggled to make ends meet a few years before he died. The old veteran had denied himself necessities to keep his ailing wife, Johanna, alive without asking for charity. He had to sell his possessions so that he could pay the rent.

Before the welfare state, there were few options for old soldiers like Clay – poor relief from the parish, begging or the workhouse. The Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 established ‘workhouses’, and to cut the cost of poor law provision they had brutal conditions like prisons to deter the poor from turning to them. The regime would have meant the separation of married couples like the Clays. A few of the lucky ones got pensions from the Chelsea Board but few, like Tom Plunkett, who was wounded in the head at Waterloo, passed the interview; he was discharged with just 6d a day.

Sergeant Clay’s plight was eventually discovered after his wife had died by a General Codrington, who wrote letters to The Times that led to a charitable fund for Clay, which soon grew to £100. ‘Unfortunately,’ said Christine Dabbs Clay:

the last enemy was too strong and Matthew died on 5 June 1873 aged 78, before he could benefit from the General’s kindness.

He died a pauper but was given a hero’s funeral and thousands of people came to pay their respects. On the top of his coffin lay his sword and a ring of laurel leaves, because when he was alive, on the anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, he wore a sprig of laurel leaves to remember that day.8

Clay’s name appears among the 39,000 who received a Waterloo Medal for their service. The medals were issued to every soldier who had served at Waterloo, Quatre Bras or Ligny – the first time in British history a campaign medal had been issued to everyone who took part, including the ‘common soldiers’ who were drawn from the ‘scum of the earth’. Recipients were credited with two years’ extra service and pay, and a holder was known as a ‘Waterloo Man’.

The silver medal carried the head of the Prince Regent on the front with the inscription ‘GEORGE P. REGENT’, while the reverse carried the seated figure of Victory with the words ‘WELLINGTON’ and ‘WATERLOO’ below and the date ‘JUNE 15 1815’.

There is a portrait of Clay in the Guards Museum in London. He is proudly wearing his scarlet Guards post-Waterloo uniform, with the Waterloo Victory medal, but it is reversed; the side with the Prince Regent’s head is turned against his chest. A note by the Guards Museum is quite frank, given their close proximity to royalty (Buckingham Palace is across the road). It says he may have worn it reverse up, because he ‘did not like the Prince Regent who was not popular’.

On his discharge papers, Clay was described as ‘a very good and efficient soldier, never in hospital, trustworthy and sober.’ The Guards Museum note points out this was high praise, given drunkenness was a scourge of the army, ‘paralleled by the pox’.

Life for James Graham after Waterloo was bittersweet. James’s brother, Joe, died within a week from his injuries, despite James’s heroic efforts to save him from the flames. Then after only two years, Norcross stopped paying his pension.

The reason why Norcross withdrew the annuity speaks volumes about the hard times suffered in Suffolk. The Curate’s Living at Framlingham was worth £1,300 per annum and, in addition to the Rectory of Framlingham – described as a ‘fair mansion house’ (now converted into six flats) – there were eighteen pieces of glebe land covering 70 acres, making it the richest of ten benefices in the gift of Pembroke College, apart from the vicarage of Soham in Cambridgeshire. Norcross became a victim of the hard times that hit rural areas after Waterloo, particularly in the Fenland country of Suffolk and Norfolk. Bad weather resulting from the effects of the Tambora volcano led to a huge fall in crop yields and farm incomes in 1816. Wheat yields in England fell from 37 bushels per acre (bpa) in 1815 to 25.3bpa in 1816 (a drop of over 31 per cent). Farmers could no longer afford to pay the tithes – a tenth of their income – that made Framlingham such a rich living or pay their farm workers. The bad weather added to the misery for the 250,000 ex-soldiers looking for work. East Anglia today may seem like a sleepy rural backwater, but it witnessed riots in 1816 at Littleport and Ely over the economic distress.

Former BBC Newsnight presenter Jeremy Paxman stumbled across the story of the hardship in Framlingham in his programme for the BBC series Who Do You Think You Are? Paxman discovered one of his own ancestors, Thomas Paxman, an impoverished shoemaker in the village, had to turn to parish relief for regular hand-outs of ‘dole’ money for his family to survive. His ancestor was literally the poor man at the gate. Paxman, noted for his hard interviews, was moved to tears when he found in the parish accounts Thomas Paxman going for regular hand-outs from the dole office at Framlingham Castle – 6s 6d in one week, 7s 10d in another – for months. ‘Every week, he is turning up with his hand out,’ said Paxman.9

Thomas Paxman joined a long-forgotten migration scheme from the Fens to work in the ‘satanic mills’ of the North of England. It split the Paxman family. A migration agent arranged for Paxman to be transported by canal barge with his wife and four of his seven children, but only those who were over 12 and permitted to work in factories were allowed to go. They were put to work in textile mills in Bradford, while the younger Paxman children were left behind to be looked after by in-laws.

Andrew Phillips, a local historian, told Paxman: ‘Anyone who is anybody gets the hell out of Suffolk.’

Poverty and the post-war slump led to a nasty dispute between the tenant farmers and Norcross. The farmers could no longer afford to pay the tithe and Norcross reluctantly stopped paying Sergeant Graham his Waterloo pension after only two years. Graham was told Norcross was ‘declared bankrupt’ but this is another of the myths surrounding his bequest. Norcross did not go bust. However, he was clearly so upset and embarrassed that he moved with his wife Eleanor to Dawlish in Devon, where he died in obscurity in March 1837 aged 75. While he kept the living at Framlingham, he paid for clergymen to conduct services in his absence.

Graham, like Clay and other old soldiers, faced hardship when his fame faded. His official discharge papers from 1829, which I have obtained, show that within a year of Waterloo the hero of Hougoumont was reduced to the rank of private, no doubt with a cut in his pay. He was discharged by the Coldstream Guards on 24 July 1820 for reasons not given and the next day, 25 July 1820, he was signed on as a private with the 12th Dragoons, who were then in Ireland but later posted to Portugal during a civil war. He clearly had a rough life, because he was finally invalided out of the army with a severe chest injury, caused when his own horse fell on him, which must have been an occupational hazard for the Dragoons.

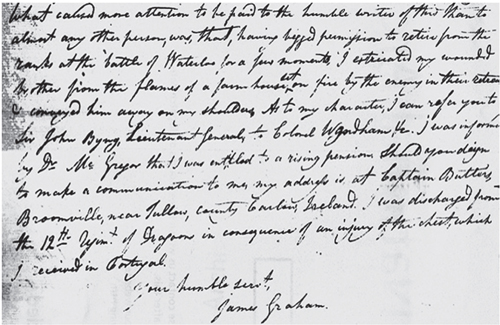

Discharge papers of Sergeant James Graham.

His army record says he was discharged ‘in consequence of worn out constitution and a severe injury of his chest by his horse falling back with him in Portugal in July 1827’. His conduct was described as ‘good’, his age was ‘about 38’, his height 5ft 9¾in, with brown hair, grey eyes and fair complexion. His trade was given as ‘weaver’, though he had been in the army since 25 March 1812, when he joined the Coldstream Guards at the age of 21. His total service, including two extra years for Waterloo, was 19 years and 294 days. He was given a ‘Chelsea’ pension of 9d a day on 13 January 1830. That is pitiful sum for a national hero.

James Graham was from Clones, County Monaghan – he is said to have been one of three brothers who joined the British Army (possibly including John Graham, the soldier discharged because he was ‘undersized’). I could find no contemporary description of James, but there is a crudely drawn pencil portrait of James Graham in the national portrait gallery in Dublin. He has long, jet-black curly sideboards, giving him the dark handsome looks of a gypsy or the singer Tom Jones in his prime. He is wearing his scarlet tunic and a post-Waterloo shako topped by a green plume and a stringed bugle badge, denoting a light company. He is wearing a medal, possibly the Waterloo Medal, but like Clay it appears he wore it reversed as a mute protest to the times. A memorial plaque was put up to his memory at Kilmainham in 1906 saying:

To the Glory of God and Sergeant James Graham 2nd Btn Coldstream Guards Born 1791–1845: He was one of the five Coldstreamers who successfully defended the main gate …

However, after the Irish Free State was created, Kilmainham was taken out of the hands of the British and Graham’s fame was all but forgotten. An eminent Dublin surgeon, Seton Pringle, who was also a Clones man, arranged in 1929 for the plaque to be put up in the protestant St Tiernach’s church that towers over the cobbled square in Clones.

A plaque praising a hero of the British Army may seem incongruous there now. Clones is in the Irish Republic, a strongly Republican area, hard up on the border with County Fermanagh and it has seen its fair share of the Troubles. It was the scene of a bloody shoot-out between the IRA and the special constabulary in 1921, when one IRA man and four constables were killed. A farm in Tirconey with links to the Graham family was firebombed in the 1970s when Billy Fox, an Irish politician, was murdered. I asked one of the locals in Clones whether the 200th anniversary celebrations for this hero of the British Army would be a cause of pride or embarrassment in this strongly republican border area. He told me: ‘I don’t think there will be any embarrassment – it’s just that there aren’t many here who know who James Graham was.’

The archives on Sergeant Graham today are surprisingly elusive for someone who was a national hero. His Irish records are thought to have been destroyed by fire at the national archive in Dublin in the Republican uprising of 1922. Graham’s army records held by the Coldstream regiment may also have gone up in flames with their other archives in the 1940–41 Blitz.

In 1904, the War Office made a search for his papers after a relative in Toronto, Canada, made some inquiries. They found nothing, because they got his name wrong: they looked for ‘John’ Graham instead of James. Finally, after months of correspondence, they made inquiries under the right name and his discharge papers were found at Kilmainham Hospital. A set was kept in London (now at the National Archives in Kew)10 and, with the help of researcher Kevin Asplin, I was able to read them again. They reveal that in July 1835, James Graham – perhaps still suffering with the chest injury – was driven by poverty to appeal to the board of the Chelsea Pensioners’ Hospital for ‘an augmentation’ of his meager army pension.

His letter, in his own spidery handwriting, was sent on 23 July 1835 – after struggling for five years on his army pension of 9d per day. It is a poignant and remarkable document. As far as I know, it has not been published before and it speaks volumes of the hardship suffered by some of the heroes of Waterloo, like Graham. He addressed his letter to the Right Honourable Commissioners of Chelsea Hospital:

Gentlemen,

Having served in the Coldstream Guards for 8 years and in the 12th Dragoons for 9 years and six months, 2 years of Waterloo service, and having been discharged on a pension of 9d per day, I am induced to write to you hoping that you will take my service into consideration and grant me an augmentation of pension. The Rector of Framlingham in Suffolk, soon after the battle of Waterloo, wrote to the Duke of Wellington, stating that in his opinion the non-commissioned officers of the British Army that for their conduct on that day, entitled themselves to some distinct mark of their country’s approbation and therefore felt disposed to offer his humble tribute to their merit. In order that this might be properly applied, he requested that his Grace would point out to him the non-commissioned officer whose valorous conduct, from the representations which his Grace had received, appeared the most meritorious to whom the Rector meant to convey in perpetuity a freehold farm value £10 per annum. The Duke set the inquiry immediately on foot through all the commanding officers of the line and in consequence learned that a Sergeant Graham (the writer of this) of the Coldstream Guards and a corporal of the 1st Regiment of Guards [believed to be Private John Lister of the 3rd Guards] had so distinguished themselves that it was felt difficult to point out the most meritorious. But the Rector having become bankrupt, as I was informed by Colonel Woodford, now Major General, I received the £10 but two years. I had two brothers at the battle of Waterloo, one serving under Colonel [Frederick Cavendish] Ponsonby [of the] 12th Dragoons, the other under Colonel McDonald and Colonel Woodford. What caused more attention to be paid to the humbler writer of this than to almost any other person, was that, having begged permission to retire from the ranks at the battle of Waterloo for a moment, I extricated my wounded brother from the flames of a farmhouse set on fire by the enemy in their retreat and conveyed him away on my shoulders.

As to my character, I can refer you to Sir John Byng, Lieutenant General to Colonel Wyndham. I was informed by Dr McGregor that I was entitled to a rising pension … I was discharged from the 12th Regiment of Dragoons in consequence of an injury of the chest, which I received in Portugal. Your humble servant, James Graham.

He said if they should ‘deign to communicate’ with him, the commissioners could write to him at ‘Captain Buttens, Broomville, near Tullow, County Carlow’, which is south of Dublin in the Republic of Ireland. I could find no record of any additional pension being paid to him, but it seems likely that the Commissioners eventually decided to admit him to Kilmainham on 1 July 1841, where he died four years later at the age of 54 and was buried with full military honours.

Part of Sergeant James Graham’s letter.

And there is no sign of Graham at Kilmainham, modelled on Les Invalides in Paris, which now houses the Irish Museum of Modern Art. I was told ‘it does seem that the nineteenth-century headstones for “Rank and File” soldiers buried in the Hospital grounds have all been removed’. As a result, although Sergeant Graham’s heroism will be celebrated with the bicentenary of the battle, it is unclear where this national hero was buried.

There was one other intriguing story about Graham I had to track down, however. The Navy and Military Gazette edition of May 1845 reported Graham later performed another act of heroism, saving the life of Captain (afterwards Lord Frederick) FitzClarence of the Coldstream Guards and helping to stop a plot to assassinate the Cabinet, including the Duke of Wellington.

* Hougoumont is rising from the ashes thanks to Project Hougoumont, the Walloon authorities and a donation of £1m from the taxpayer by Chancellor George Osborne, who turned out to be a battlefield enthusiast.

* Ramsay’s body was disinterred three weeks later and taken back to his native Scotland where he was reburied.

* The metal lock is on display in the Guards Museum, Bird Cage Walk, London.

* Wellington’s message on a strip of ass’s skin is preserved at the Wellington Museum, Apsley House.

1. Charles Dalton, Waterloo Roll Call (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1904), p. 212.

2. Major-Gen H.T. Siborne (ed.), Waterloo Letters, (London: Cassell and co., 1891), p. 262.

3. Ibid.

4. Colonel Petiet, Memoires du general Auguste Petiet, hussar de l’Empire (Paris: Kronos Collection, Spm, 1997) p. 443.

5. Major-Gen H.T. Siborne (ed.), Waterloo Letters, p. 256.

6. Daniel Mackinnon, The Coldstream Guards (London: Richard Bentley, 1833), p. 217.

7. Wellington Despatch to Lord Bathurst, Secretary of State for War, 19 June 1815.

8. Matthew Clay, note by a family descendant Christine Dabbs Clay, Blidworth and District Historical and Heritage Society.

9. Who Do You Think You Are, Series Two, Acorn Media, 2006.

10. WO 97/55, War Office papers, National Archives, Kew.