Peeta hai hamesha chai!

(I always drink chai!)

— Traditional Hindi Saying

Everyone who travels to India returns home transformed, altered in some way by the experience. Each gift from this awesome country is different, but certainly tea will be among the many lingering memories, and masala chais head the list of teas savored.

The triumvirate of teas from India grow mainly in the regions known as Darjeeling, Nilgiri, and Assam, and all of these teas are from varietals of the plants Camellia sinensis or Camellia sinensis var. assamica. What makes teas from these three areas taste so similar yet so different? The answer is twofold: how they are grown and how they are processed.

Theoretically, any tea grown anywhere in the world could be processed green, oolong, or black. Even the young buds can be processed as white tea, or the leaves aged as pu-erhs. However, not all teas lend themselves to all three processes; processing, as well as desired flavor in the cup, depends on location, altitude, weather (particularly the type and amount of rainfall), and the agricultural work.

No matter how ideal the weather, how perfect the location, or how careful the tea bushes are maintained and plucked, it is critical that the processing method be a viable combination of art and science. The level of skill and attention of the workers, in conjunction with well-designed and -maintained machines, can bring out the absolute best flavors of the tea leaves, develop a beverage that is so-so, or worse, ruin the tea. The same attention is paramount with tea leaves that are hand-manipulated in the old-style method of careful heating in stone woks.

Nonetheless, for the passionate tea drinker, the choices are increasing at an amazing rate.

Sarra Baraily was born and raised in Mussoorie, India. She lives in Michigan with her husband, Krishna, a violin teacher who plays in the Kalamazoo and Battle Creek symphony orchestras, and her daughter, Anjuli, now eighteen and a university freshman majoring in voice performance. Sarra works for Michigan State University in the College of Human Medicine.

Even though my husband, Krish, and I have been away from our native India for almost sixteen years, we have only been able to visit home a few times. One such visit was in August 1991, the only vacation time available from our work. In India, August is usually the tail end of the monsoon season, with strong storms, days of heavy mist and rain, and lush, dripping green foliage everywhere.

That August was rare and delightful: The monsoon had started to drift away in the early part of the month, so when we arrived on the 9th, we were met by clear days of bright, hot sun rising up over the Kònòchenjunga Mountains just 40 miles across the blue-green valley.

It was also a time of political trouble between the Nepali residents of Darjeeling and the Bengalis. The Nepalis were agitating for a state separate from Bengal, to be called “Gurkhaland.” Although this has since become a reality, leading to greater prosperity and a stable economy in Darjeeling, during our visit the agitation forced my family and I to take a circuitous route to Darjeeling.

Normally we would have taken a small sedan taxi to Darjeeling up the moderately wide paved road that winds gradually through the forests to emerge into open expanses of spreading tea estates all around the road: gnarled, stunted bushes, some dating back 150 to 200 years, but shiny and green leaved due to frequent plucking and pruning. You could step out of the taxi, walk over to a bush, pinch the leaf, and inhale a delightfully spicy, pungent fragrance.

Because of threatened political demonstrations on the road that year, though, we took a Land Rover taxi from Siliguri, the rail head from Calcutta at the base of the hills, up the Pankhabari road, which is only slightly wider than a bike path. The narrow road soon steepened to almost a 45-degree angle, forcing our vehicle to the limit.

The Pankhabari road is overgrown with bamboo and pine, cryptomeria and wild orchid, a truly adventurous jungle of a route. Despite the steep climb, we were exhilarated by the sun, by the luscious green rice-field valley stretching away below us as we made our way up into the coolness of the Himalayas, and by the anticipation of coming home.

The soft whistle of a steaming kettle of water is the most soothing, comforting sound in the world.

Halfway up the hill the road suddenly leveled out into a bountiful tea estate. We were so close to the tea bushes that we could have stuck our hands out the windows and plucked a few leaves. Getting thirsty and tired of riding in the bucking jeep, we casually asked our driver if he knew of any tea stall nearby. He nodded diffidently and a few minutes later braked with a rush beside an impossibly small wooden shed built over the khud (hillside) of shining green tea bushes stretching for what seemed to be miles.

A cheerful Nepali woman appeared at the window of the shed. When we asked if she had some hot tea, she smiled broadly, reached in front of her and opened the window further to display glass jars full of hard candy, biscuits, and tea. Behind her we could see a teakettle on a brazier, already beginning to steam.

Lowering our heads to get through the small door opening, we made our way to the back of the shed, delicately held up by wooden stakes so as not to obstruct the growth of the tea bushes. We sat down on wooden stools and the tea lady brought in a tray of hot milk, grainy sugar, large chipped porcelain cups, and a teapot of the best Darjeeling tea I remember ever having: freshly picked large tea leaves that unfurled slowly in just-boiled water with a fragrance and taste that rivaled anything else in the world.

In this rare moment we were happy captives of tea’s beauty and magic: the smiling face of the woman; the driver and my husband speaking softly in that lovely language of Nepali; Anjuli, our then eleven-year-old daughter, melting back into her childlike self, gazing around with wide, accepting eyes; and I watching and feeling it all, not able to say a word from the pleasure of realizing we were home.

The teapot drained, we continued on up the hill to the waiting arms of our family.

The growing of teas depends upon altitude, climate, soil, and the attentive plucking of the leaves at just the right time of the year. Processing generates three basic categories of tea: greens, which are barely withered, and not oxidized or fired at all; oolongs, which are partially fired, retaining much moisture; and black teas, which are 100 percent fired. Greens taste grassy and fresh; oolongs are intensely and naturally perfumed and sweet; blacks are crisp and sharp and cleansing on the palate. To tea lovers these are but generalities because teas change from plucking to plucking, from season to season, and from area to area, making the lure of the leaf as intoxicating as the lure of the grape is to the wine connoisseur.

Other tea categories are whites and yellows, both made from the small, tender buds of high-quality tea plants; these have a delicate sweet taste and pale color in the cup. Whites and yellows are rare in India, and more common in China, although some white Assams have come to market and provide a remarkable cup. There is a sixth category of tea, an intentionally aged tea called pu-erh, made primarily in China. In India aged Darjeelings, called vintage teas, offer a unique and complex taste in the cup.

The process of drying leaves, molding them into myriad shapes — such as pellets, pearls, or smooth elegant leaves — then oxidizing them in special ovens is more art than craft, and perhaps the most fascinating attraction of tea besides its taste. Machinery does most of the work these days in India, but many estates still provide hand-processed teas in limited quantities.

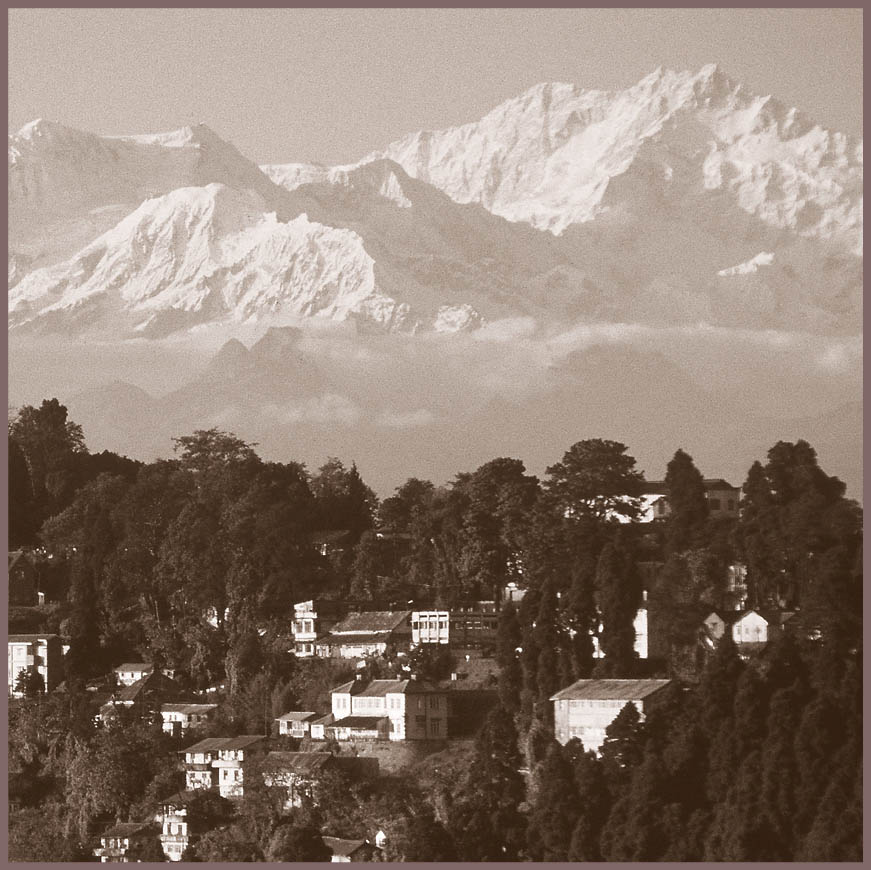

One of the three primary tea-growing regions in India, Darjeeling is a beautiful area in northeastern India, south of Sikkim. Surrounded by the majestic snow-covered Kònòchenjunga Mountains in the foothills of the Himalayas, Darjeeling’s the lucky recipient of heavy white clouds that continually mist the tea bushes.

To describe the flavor and style of Darjeeling teas without mentioning the phenomenon of location is impossible, because the soil, elevation (often as high as 6,500 feet), and weather (heavy rainfall and at least five hours of sun a day are necessary) count as much as the planting, plucking, and processing.

For many years I avoided Darjeelings, believing they were too astringent for my taste. Then a Darjeeling tea enthusiast suggested that I prepare this Indian nectar in the Chinese style, with hot water (190–200˚F), steeping for 2 to 3 minutes only in a covered Chinese-style cup. Ah, now I understood the passion. Darjeeling is truly a flower in a cup, delicately perfumed, exquisite flavor notes, enormously satisfying.

As with any variety, Darjeelings vary from estate to estate and the choices are vast. (There are now eighty-six estates, producing about 11 million kilograms of tea annually.)

Most fine Darjeelings are sold by the season in the best grades and in whole leaves. A first flush is picked just after winter, usually from March through April, when the leaves are naturally spring-tender and lighter and greener in appearance. The second flush, perhaps the most sought after for its “muscatel” flavor, has a red-brown color with a slightly fruity taste. This is picked usually during May and June. The rain teas, picked generally from July through September, have an astringent yet bright taste. Autumnals are plucked in the fall, generally between October and November, and these teas are considerably more mellow in taste and character.

Two lesser known areas grow some commendable teas: the Dooars and Terai. Teas from the low-grown Dooars fall between the strength of an Assam and the delicacy of a Darjeeling. Teas from the plains of Terai offer a spicier bite than their Darjeeling relatives, and blend well with other teas. They take well to milk.

Teas like those in the Terai or Dooars may share some of the flavor characteristics of Darjeelings, but without the exceptional elevation and weather of the foothills of the Himalayas these teas never can duplicate the exquisite flavor, aroma, or even color of the finest Darjeelings.

Some tasters categorize Travancore tea with Darjeelings. This is actually a southern Indian tea that tastes more like a Ceylon, but some tea sellers classify it as a Darjeeling because of its similar astringency. It has a strong, full body that takes well to milk.

Whenever you can, try to purchase your Darjeelings from reputable tea shops that carry single-estate teas. Most commercial Darjeelings are blends (and many good ones at that), but to truly “taste Darjeeling” you must try single-estate teas. They are an investment in pure pleasure. For a complete list of the gardens of Darjeeling, see here.

A Chinese covered cup, or guywan, is my favorite way to savor Darjeeling tea.

Sharing his impressions of Darjeeling is Mike Olsen, co-owner of Time for Tea, a tea salon in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, which sells bulk teas from around the world, and in particular, fine Darjeelings.

How many ways are there to describe Darjeeling? Perhaps as many as there are languages in India. For me, my lasting impression is of standing on the foothills of the Himalayas watching the clouds pass below, feeling the magic that is Darjeeling.

The first thing you notice upon arrival at a tea estate is the aroma of the verdant tea bushes. Tea’s musky, rich scent is noticeable whether it is pouring down rain or a perfectly clear day. You notice it most as you approach the fields. (At home, you can approximate the intoxicating atmosphere if you hold your nose right down into freshly brewed tea leaves.) The smell is one of so many things you take with you when you leave Darjeeling.

Without a doubt Darjeeling is one of the most beautiful places in the world. From the plains of the Dooars, to the steep slopes of the midranges, to the rolling hills at the higher altitudes, the land is an ocean of green. No wonder it’s referred to in Indian folk tales as the land of thunderbolts or land of the dancing mists. The geography alone is worthy of legends.

Everything comes together in Darjeeling. The mountains are placed to funnel the proper air currents, which in turn bring the rain clouds at the right time of year. The sun fills the slopes with the proper amount of light each day. Clouds drift through, providing the humidity for the tea plants. Mother Nature prepared this land, yet when humans took an innocent bush and began to cultivate it, the combination became what perfection can be.

We are all beneficiaries of this serendipitous combination of Mother Nature’s canvas and the tea planter’s vision.

Within a land of superlatives is a small shining emerald with a name that means “place of corn,” Makaibari Tea Estate. Arriving at this estate, near the town of Kurseong, was a relief after a week of the 117˚F days in Delhi. The weather was perfect during this first week of June when it was only in the 70s and the threat of monsoons was weeks away.

Makaibari Tea Estate is truly a wonder. Heavily forested, it hosts the widest biodiversity of any tea plantation in the world with 2 acres of tropical forest per acre of tea and a staggering array of flora and fauna. On several occasions I was warned not to be eaten by tigers, and I suspect that my hosts were only half joking. Makaibari’s owners have an extraordinary commitment to the land. As a result, they produce tea as pure as any you will taste, a golden jewel in a cup.

The Banerjee family, owners of Makaibari for several generations, provides jobs, schools, land to grow food, and a safe environment for the tea pickers and their families. Managers are not remote or standoffish; they and the pickers know one another and work together to create a tea that is truly special, the only organic, purely biodynamically grown tea in the world.

The majestic Darjeeling mountains appear to rise out of the mist.

The amount of work that goes into making a pot of tea is mind-boggling. A general familiarity with tea production doesn’t prepare you for what you see in person. After praying that the weather cooperates for the best possible growing conditions, tea producers begin the delicate art of processing.

On a very basic level, tea production involves the manipulation of water: first providing it, then taking it away at critical points. Water is needed to nourish the tea plant; later it is removed in the processing of the harvested leaves; then the tea must be protected from water during its transport and storage; finally, once it is delivered to the consumer, water is again added to bring the tea leaves back to “life.”

Tea must be picked at the proper time. It will not wait for you. The tea is picked with care, primarily by women. It is generally held that women have a much better connection to the earth and work harder than men, but it also may be true that wages paid to women are sometimes lower than those paid to men. Some other jobs are considered more “important,” and, thus, should be done by men.

The tea is transported to withering bins and spread 6 inches deep on screens before processing. Air is circulated, and the temperature is regulated depending on the humidity and how much moisture is to be removed from the tea. Then the tea is off to the rolling machines to undergo two separate rollings with a rest period between. After twenty minutes or so in drying machines, the tea is sent through a room of great shaking belts, screens, and chutes, which separate the leaves by size.

The tea harvested from each plot of land is processed separately, and tasted on a daily basis. It is a fascinating experience to taste the same tea several days in a row, to see how its character develops. Different leaves are blended to achieve maximum potential of the projected taste in the cup. Then the tea is again allowed to rest before it is shipped off to reveal itself to the consumer.

Any stage of the production can alter the flavor of the tea, and the utmost care must be taken. Tea is a forgiving plant . . . as long as you give it constant attention. A bad call at any stage will produce something unpalatable.

The flavor of Darjeeling has changed; today’s Darjeeling is distinctively different than in years past. The axiom that a good Darjeeling tea is an astringent, intense brew is no longer valid. Teas that were produced from a hard wither for Russian palates in the 1970s and 1980s are now being made for a much more sensitive palate. Individual flavors are discernible, allowed to flourish. Each year brings more complex, fascinating teas.

The plant itself is changing, too, as a result of interplanting, clonals, and other techniques used to develop a better leaf on the bush for a better, more consistent taste in the cup. Tea cuttings were first brought to India from China by Robert Fortune and planted throughout Darjeeling. These smaller, tender Chinese plants were unable to fend off such foes such as red spider, green fly, and mold. Clonal varieties of the Assam plant, cultivated to be hardier, produce more, and have a shorter growing time, have been added to Darjeeling estates to make those teas healthier. As a result, the classic Darjeeling flavor has slowly changed.

Despite its fragility, the finer-leaf Chinese variety is still used to give Darjeeling its outstanding flavor, the bright, intense wash around the mouth. To make the tea bushes healthier (and more resistant to bugs), some estates plant with a higher ratio of Assam to Chinese plants. The two varieties of tea bushes grow together in the fields but are kept separate all the way through processing, to be blended to the taste of the tea maker. Darjeelings with the taste of Assam have the added benefits of a rich red tint and a fuller flavor in the final cup.

One exception to this trend is the Makaibari Tea Estate, which replants tea bushes in the traditional ratio and plants with seedlings and clonals only. This is quite time consuming and difficult, but worth the results in the cup. Makaibari also uses nothing unnatural on its biodynamically grown tea plants: no pesticides, no chemicals, nothing that is not natural.

The processing of tea into greens and oolongs in addition to the conventional blacks is a major shift among Darjeeling growers. Some estates are producing green and oolong varieties in skyrocketing amounts, with brilliant results — so much so that on several estates Chinese oolong makers are studying the production methods in Darjeeling. The oolongs are full of honey on the nose and in the cup. The greens are full of peach, apricot, and other fruit flavors. (A century ago producing greens was the typical processing method for Indian tea, but as demand for tea has grown, processing tea into blacks has become more common. Blacks last longer, travel better, and blend well with blacks from other countries.)

Darjeeling is such a mystical land, it is no surprise that it produces such an outstanding tea. When we visit beautiful areas of the world, we can’t help but leave something behind that will eventually draw us back. Those of us who’ve been to Darjeeling don’t talk about someday, but about which day we will return to the people who live among the clouds.

Tea plantations are some of the most beautiful areas in all of India.

4 servings

Cardamom is an essential spice in masala chai, but chai also tastes great when cardamom is its sole spice. Try this recipe with a delicately aromatic Darjeeling. I’ve added a touch of orange for fragrance, but you can omit it.

Loose-leaf teas, whether black or green, are the premier choices for the best-tasting chais.

3 dozen cookies

Debby is a chai enthusiast who contributed this modified recipe to Gary and Jan Routh’s chai Web page. They’re light and dainty and contain zero fat. Serve with your favorite Darjeeling. Adding a puree of fresh fruit on top is a delectable touch. The pungent flavor of chai makes an excellent companion to these orange-and-almond cookies.

3 dozen cookies

Butter cookies, shortbread, and biscotti are excellent accompaniments to Indian tea, especially Darjeeling. Here is a favorite recipe of mine.

It is quite probable that you have already had an Assam tea, or a blend with “the hearty one” in it. More tea is produced in the Indian state of Assam than in most tea-growing countries of the world. The tea plants are also different from Chinese varieties or those grown elsewhere in India. They are Camellia sinensis var. assamica, a broad-leaf, hardy evergreen species that has become the most reliable tea bush in the world, capable of withstanding infestations of bugs better than other tea varietals, and able to endure the rains so common to this area.

But how it grows is not nearly as important as how it cups, and Assam tastes terrific. It’s rich and full of heavy body, some fragrance, and a bite that can stand up to milk and flavorings yet does not have the astringency so common in Darjeeling or even Ceylon teas.

Assam is excellent for blending because it adds body to those teas with thinner tastes but great fragrance, and offers other flavor notes to give any blend a more balanced, more interesting flavor profile. This is not to say that Assam is not a stand-alone tea, for it is indeed. For many people Assam is tea, and it is black tea. All these qualities also make Assam the number one choice for masala chai lovers, who realize that the richness of this tea makes it ideal to blend with strong spices.

In the early history of tea in India, all tea was processed as green tea. Soon, however, merchants as well as tea growers realized that green tea, no matter how well it is processed, has a very short life span. If a vendor has more tea than customers, there go the profits. So, like the Chinese, Indian tea processors began processing their tea into blacks to achieve longer transportation schedules and longer shelf life. This has now become the predominant category of Indian tea.

Ironically, as more and more connoisseurs have made their presence known in today’s market, more manufacturers have become willing to take the risk of making green, and even white teas from Assams. These greens and whites are not nearly as elegant as their Chinese relatives but do offer the palate a remarkable sensation — a multilayered taste profile that should be experienced.

For the finest black Assams, look for golden “tips”: points at the ends of the leaves that are golden, indicating fine processing. For greens and whites, look for even coloring and finely shaped leaves. For the heartiest flavors and the purest tastes, full or partially broken leaves are the best. Good Assams are available in all grades, but as always, the final arbiter is not the look of the leaf or its fragrance, but its taste in the cup.

Smooth, hearty black Assam teas offer strong tea flavor that stands up well to the most exotic spices and creamiest milks.

Fifteenth-century explorer Vasco da Gama reportedly requested a cutting of a pepper stalk from the potentate of Calicut (Kerala) to take back to Spain. Allegedly, the calm reply was, “Certainly, take our pepper. Alas, you can not take our rains.” This was a sly reference to the importance of the region’s twin monsoons, which are essential to the prized pepper plant’s survival.

This tale was shared by Michael Harney of Harney & Sons Teas. Michael is a graduate of the Cornell University School of Hotel and Restaurant Administration, and is the Harney company’s primary buyer of tea. His father, John Harney, founded the firm.

Driving by car down the whole of Assam is amazing. Assam is not a tourist place; it’s hotter and sunnier, with spots that are the wettest on earth from the relentless rains. It’s not unusual to see tea plantations covered with 3 feet of water from the heavy pourings of the season.

From the Dibrugarh Airport, we started our trek to Gauhati in southwestern Assam, where I had come to buy teas. The roads were rough, the travel not easy, dodging cows, dogs, and people along the way, but what a sight the tea fields were at the end of the journey: lush, lush green, the visible result of all that rain, with eucalyptus shade trees popping up here and there among the thousands of tea bushes.

The huge, wide, slow-moving water of the famous Brahmaputra River does not abut the tea farms (it flows a few miles away), but it’s quite a sight to see how the river changes from its flat beginning in the north of India to its mountainous swing up to China and Tibet. I remember looking at it from the airplane and thinking it was like a magnificent silver ribbon cutting through this emerald green region called Assam.

We arrived at the first tea farm about closing time, when the women tea pluckers were walking away from their task of picking the very large Assam leaves. They wore the most beautiful saris, gorgeous silks of vibrant colors accented with yellows to catch the sun. They moved as gracefully as trained dancers despite the precarious balancing requirements of a tower of items on their heads: wide-brimmed hats, heavy baskets full of tea leaves, and on top of that umbrellas for the constant rains. It was a breathtaking introduction to Assam.

The tea pluckers there have a very complex job, enduring the volleying sun and rain almost daily and certainly through much of each day they work. However, because the leaves of the Assam plants are so big, these women can pluck them more easily than the smaller Chinese varieties in Darjeeling — they can fill up their baskets quicker and fill more baskets per day. Still, it’s such hard work that we could not help but admire such tenacity and diligence.

The long, flat fields of the Assam farms we visited were fragrant with the sweet malty smell of fresh tea leaves. The heat and dampness of the fields provided a surprisingly sensual experience; the fragrance was intoxicating in the gardens, and in the facility where the withering (drying) and processing are performed. It was tea heaven.

It was quite fascinating to watch the crush, tear, curl (CTC) pellet machine where the bright green fresh leaves traveled the long, long conveyer in its slow travel for at least an hour. Oxidizing along the way, the green leaves turned brown naturally along this 100-foot path, as a cut apple would when exposed to the air. Then the lightly withered leaves were placed into a special oven to oxidize a full 100 percent. (Green tea is not oxidized at all, and oolongs are oxidized 2 to 80 percent, depending on their various styles; all blacks are oxidized 100 percent.)

In the processing of Assam tea, leaves are often intentionally cut up because they are so large. They sometimes require the additional step of filtering with a cylinder sieve. If the leaves are not small enough to sift through, they are run through a machine again to break them into smaller pieces.

Unlike Darjeeling tea leaves, Assams are generally processed by the CTC method to accommodate the enormous demand from India itself. India’s taste is for CTC tea, which is cheaper, is plentiful, and lasts longer.

The market for loose, full-leaf teas is always risky. These teas have a shorter life span and so must be sold more quickly and drunk sooner than the long-lived CTC tea. And as in any agricultural business, the need for freshness makes all produce vulnerable, even a dried leaf like tea. Still, you can pay almost as much for a high-quality, uncut, loose-leaf Assam as the finest Darjeeling. The quality, I am happy to report, is improving continually, and the potential for even better teas in the future is enormous. So the inspiration to create fine Assams remains.

The tea pluckers balance large baskets on their heads. Throughout the day, they will collect several baskets full of leaves.

Assam is well known as a good blender that offers lots of body. Its fragrance is less intense than other Indian teas, particularly Darjeeling, but the honey flavor in the best Assams more than compensates for the lack of aroma. The familiar maltiness in the medium grades is satisfying and continues to be very popular.

Exceptionally fine cloning has created intensely rich Assams with beautiful gold tips, especially on the Jay Shree Gardens (Meleng, Towkok, and Nahorhabi). These pretty gold-and-black teas offer a taste that is not too astringent with good body, some of the best Assam has to offer. Assam is my tea of choice for the morning; I especially like the Nahorhabi, and I drink it plain. These teas are perfection the way they are, so why mess with perfection?

Assam is very approachable, the black tea most people know best, and certainly one of the best-selling loose teas our company markets and the most popular Indian tea sold anywhere. We use a blend of Assam teas of both CTC and full-leaf manufacture to give our chai a heartier taste. Called Indian Spice Tea, it has a clear, clean note from cardamom and cardamom oil, and a spicy backdrop from cinnamon.

We’ve discovered that there is a big, enthusiastic market of people who like to add their own touch when making chai at home; this dried mixture is the perfect recipe for them. Consumers can make it as milky, as sweet, and as fresh as they desire, and if they like other spices, they can add whatever suits their mood.

Tea leaf plucking is a complex job requiring concentration, stamina, and skilled hands.

4 cups

6 dozen cookies

These delicately scented cookies are an unusual and addictive twist on the traditional sugar cookies. Buy only the best green cardamom pods and grind them yourself for the best results. White cardamom makes the dough whiter but the whitener comes from bleaching. I think the light flavor of cardamom fills up all the senses, making these the perfect accent to the rich, satisfying cup of any Assam.

I rolled them up in a cumin swamp

and in a heap of pepper dust

till they were spiced and hot enough

to twist your tongue and burn your mouth.

When they were basted well with oil,

I didn’t wait to wash or sit;

I gobbled that mess of koyi fish

as soon as they were fried.

—Anonymous (1148), “Subhasitarantnakosa,” translated by Daniel H. H. Inglas

In the south of India stand the fragrant Blue Mountains, or Nilgiris, redolent with the scent of tea bushes, thousands of blue gum cypresses, and even more eucalyptus trees. The latter are so popular that eucalyptus oil, used for many medical applications, is known as Nilgiri oil.

Nilgiri teas have established themselves as a third choice in the triumvirate of Indian teas, but they have not received the prestige of Darjeeling nor reached the huge production of Assam teas, although that gap is closing. Of the three tea-producing regions Nilgiri has the highest production per capita, because more of its land mass is devoted to tea farms than is Assam’s. The potential to outstrip Assam in overall production certainly exists.

The natural lovely fragrance of Nilgiri teas has always been considered important in blends. It was not until the late twentieth century, however, that Nilgiri teas developed the significance they now have as stand-alone teas (like Darjeelings).

Nilgiris are like good everyday table wines: reliable, with good color and a heavy nose. They fall between the two extremes of Indian tea, the hearty Assams and the delicate Darjeelings.

For decades much of the production from the Nilgiri region was sold to locals, to the Russians, and to Iran and Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Egypt, all of whom favor the rich, dark CTC (crush, tear, curl) teas. Nilgiri tea appeals to these cultures because of its strong taste, dark color, increased caffeine, and ability to stand up to milk.

Russia’s economy is so fragile that its people can no longer afford the orthodox Nilgiris that used to make up 50 percent of their purchases; indeed, they barely can afford the lower-priced CTC. Russia’s loss is now America’s gain. The versatility of Nilgiri tea means that tea lovers can choose between delicate orthodox teas from high-end estates and stronger CTC teas from the small farms throughout the region.

Nilgiris are ideal for experimentation, creating popular oolong and green varieties that never spoil in the cup from oversteeping. Nilgiri’s innate ability not to cloud, to always proffer a clear and vivid color, makes it the perfect choice for what makes up 85 percent of the U.S. tea market: iced tea.

Nilgiri teas have another attribute: Their soft flavor makes them wonderful foils for flavorings, scents, and fruits. Such teas easily constitute 35 percent of the hot-tea market in the United States.

All good chais start with a brew of hot, strong, and fragrant tea.

Assam teas are great in tea bags or for making fresh chai at home, but Assam does not fare as well in liquid concentrates, which sometimes become bitter upon reheating. Fortunately for manufacturers and the increasing numbers of consumers who want easy liquid concentrates, Nilgiri tea is being used more and more for its goof-proof preparation. Reheating is no problem — the flavor of the spices is kept intact and the tea taste remains authentic because Nilgiri teas are hard to overbrew. What could be better than a tea that’s mellow in the cup whether used in single-estate form, in a blend, or as a tea in a masala chai?

Years of planting with clonals of Darjeeling bushes and the area’s naturally good soil quality have provided today’s Nilgiris with vibrant color, a satisfying taste in the cup, and a signature heavy yet exquisite fragrance.

A low-elevation tea like a Nilgiri can never have the delicacy of Darjeelings, which are grown at very high altitudes. Instead, the lower altitude and the lack of weather extremes found in Assam and Darjeeling provide a more consistent and richer tea in Nilgiri. Another plus is that the Nilgiri area receives light rainfall compared to the extreme monsoons of the north, which provides more pluckings per year.

Unlike the gigantic estates found in Assam and Darjeeling, most Nilgiri plantings are found on small farms of between 5 and 50 hectares. The farmers do not process the tea themselves; instead, tea manufacturers have built factories nearby, to process the leaves by the CTC method. Each factory processes the leaves of from ten to thirty farmers, and handles the sales.

Nilgiri teas are grown primarily in the Annamalais, the High Ranges, the Peerumedu-Vandiperiyar belt, Karnataka, and Wynaad in Keral. The Nilgiri region’s many high-end estates include Tiger Hill, Craigmore, and Burnside; these process right on the estate, resulting in fine full-leaf teas prepared in the orthodox manner. Such orthodox Nilgiri teas command higher prices each year. Their reputations for a more delicate taste and lighter color in the cup — ironically similar to the high-grown Darjeelings — are also growing.

Today more than ever Nilgiris are shedding their underdog status as more and more tea blenders and manufacturers recognize their good value and ability to blend with popular fruit scents and flavors. They also brew easily and with great flavor, either hot or iced, and you can choose between a dark rich cup from CTC processing and a delicate taste from orthodox manufacture of the fragrant one, Nilgiri tea. In 1998 the first organic Nilgiris were exported to the United States, another signal that these teas are rising in quality and value. See here for a list of top Nilgiri gardens.

In the sky there sounds

the comely drums of the gods,

and there blew a pleasant wind

bearing a heavenly fragrance.

— Valmiki, from “Ramayana”

4 servings

A clear, vibrant, beautiful beverage is the reliable result of iced teas brewed with Nilgiri leaves.

6 servings

This spin on rice pudding has as many variations as there are cuisines in India, but the trick to the authenticity is using basmati rice. It’s a tad more expensive, but worth it. The lovely fragrance of a pudding made with basmati is an exquisite complement to the lingering fragrance of a fine Nilgiri. A “scent-sational” way to have dessert and tea.

If there is one place on the face of the earth where all the dreams of living men have found a home from the earliest day when man began the dream of existence, it is India.

— Romain Rolland

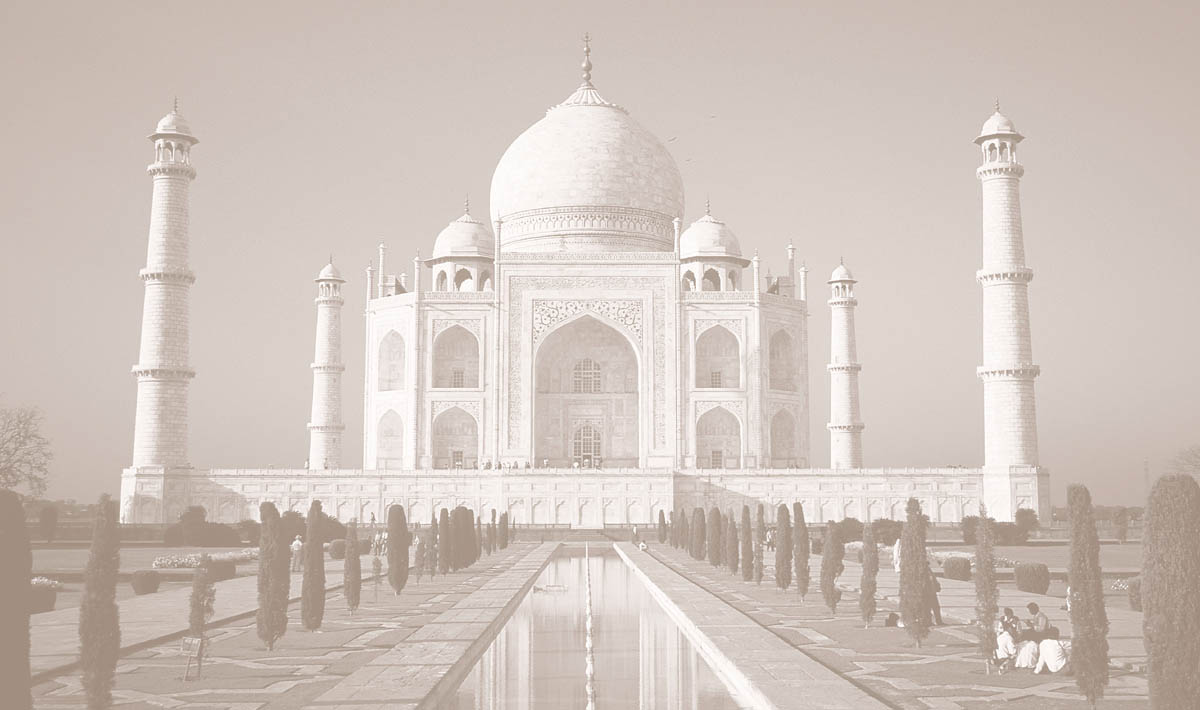

The lovely scents of fresh flowers are everywhere inside the Taj Mahal, offerings from natives and tourists who make the pilgrimage to see this monument to enduring love of the Mogul Emperor Shah Jahan for his wife, born Arjumand Banu Behum yet known to all as Mumtaz Mahal, Ornament of the Palace.

The acoustics inside are incredible. A false dome that rests in the secondary structure gives delicate reverberations whenever visiting Muslims recite the thirty-sixth chapter of the Quran, which is beautifully carved on the four main doorways of the structure in a permanent display of this traditional deathbed prayer.

Although the shah employed designers and architects, his own imprint is on the building that now rises along the banks of the river Yamuna. The grieving shah designed an identical building in black marble for himself to be placed on the opposite side of the river, but his son did not honor that wish; instead, he placed a modest gravestone for his father near the tomb of his mother, who died in 1631 giving birth to her fourteenth child. (She and the shah are actually buried in a crypt below her magnificent tomb.)

Shah Jahan had a romantic soul and genuine love for his wife, and the Taj Mahal is an eternal edifice to her memory. Still, his devotion to its construction, which he supervised from 1631 to 1654, verged on obsession.

For the twenty thousand craftsmen from central Asia and India who worked on this monument to love over twenty-two years, praise and money could not possibly have been enough payment. All met with a harsh fate: The shah had their fingers severed so that nothing like the Taj Mahal could ever be built again.

You allowed your kingly power to vanish, Shajahan, but your wish was to make imperishable a teardrop of love.

Time has no pity for the human heart, he laughs at its sad struggle to remember.

You allured him with beauty, made him captive, and crowned the formless death with fadeless form.

The secret whispered in the hush of night to the ear of your love is wrought in the perpetual silence of stone.

Though empires crumble to dust, and centuries are lost in shadows, the marble still sighs to the stars, “I remember.”

“I remember.” — But life forgets, for she has her call to the Endless: and she goes on her voyage unburdened, leaving her memories to the forlorn forms of beauty.

— Rabindranath Tagore

Terre Pasero, who lives in California, is an educator and seminar leader who teaches the skills needed to embrace diversity in the workplace. She has lived in Japan and Spain, and has traveled to many places throughout the world.

Who could travel to India and not view that magnificent monument to love, the Taj Mahal?

My friend and I had seen so many exotic sights on our travels through India, many of them recommended by friends with enormous (and justified) enthusiasm. Their voices would change to a quiet, almost reverential tone when recalling the man-made treasure in the city of Agra. Some extolled the romantic virtues of the Taj Mahal under the moonlight, others were mesmerized by its blaze of color at sunset, still others thought the magnificent tomb was more exciting at sunrise. My friend and I opted for the latter and set our alarm for 3:30 a.m. before we went to bed at our modest hotel, yet we barely slept a wink thinking of our impending adventure.

We left the room at 4 a.m., and quickly realized that getting out of the hotel was our first challenge. It was locked tight, with no one on duty to unlock the gates. Locking the hotel gave both guests and staff a feeling of security during the night, but no one realized how difficult it would be to leave.

Determined, we climbed the nearly 8-foot-high fence, and climbed down again when on the other side. We felt like burglars, although real ones usually break into a hotel, not out.

Indian cities are rarely quiet. Every street in every city seems to be constantly teeming with people, slow-moving cows, lumbering trucks, taxis, and tricycle-style rickshaws kicking up dust with every move. This moment before dawn brought a remarkable stillness . . . and no rickshaws. Determined to see the man-made marvel, we decided to hit the dust and walk the 5-mile route to the Taj Mahal.

Like a vision in the distance ahead of us came the curled body of an older Indian man, hunched over the handlebars of his pedicab in a gesture that warded off the freezing early-morning chill and gave him the appearance of a determined bicycle racer whose every breath sent steam into the air in front of him. He knew no English, but understood the words “Taj Mahal,” so we boarded his “rickety-shaw” and set off.

We arrived just in time for the sun to rise, yet nothing prepared us for the first glimpse of this magnificent mausoleum. Patterns of semiprecious gemstones, hand-set into the marble in specific patterns, caused the pristine white exterior to shimmer in the morning light. It was magic. Its overwhelming perfection hypnotized us, commanded us to be still as we sat before it for a long time, admiring the reflecting pools, catching our breath at the shapes of the tomb, reminiscent of its Damascene origins, and thinking about how it came to be built by a man besotted with grief and love for his queen.

After our trip to amazement, my friend and I walked to a little café nearby, drank some warming chai, and basked in a sweet silence, allowing the exquisite beauty of viewing the Taj Mahal at sunrise to envelop us just a little longer until the hustle-bustle of another day in India began.

The magical combination of tea and India has inspired writers from around the world.