Chapter Seven

Chai Accompaniments

From food are born all creatures which live upon food and after death return to food. Food is the chief of all things. It is therefore said to be the medicine of all diseases of the body.

— The Upanishads, 500 b.c.

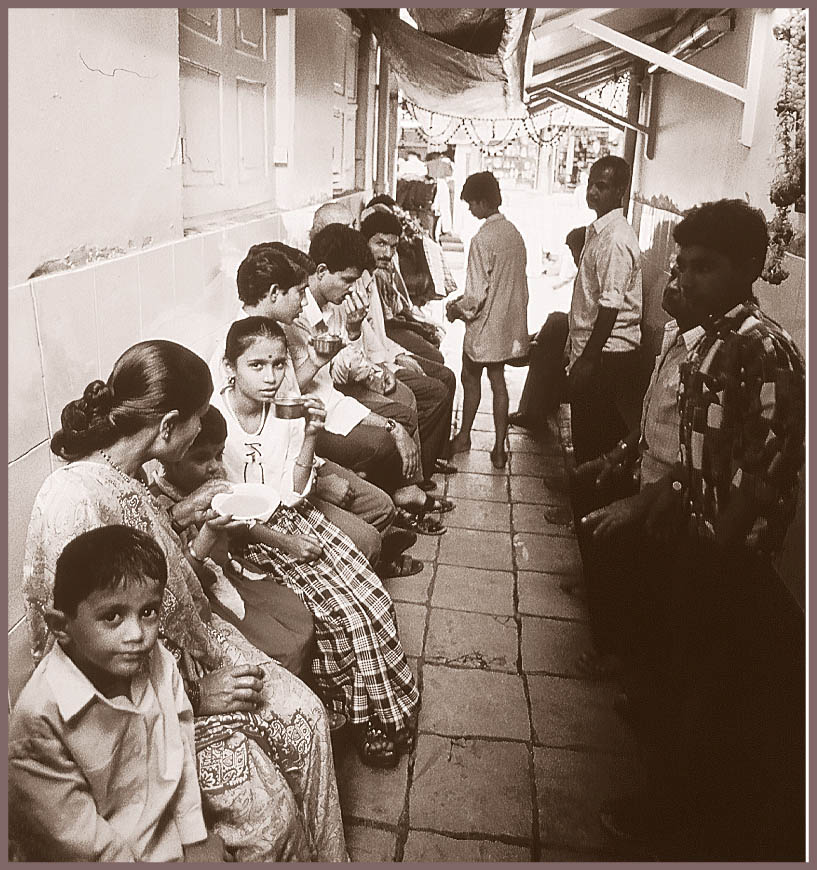

Along with its variety of religions, languages, and cultures, India has an enormous range of culinary styles. Each is itself so varied that a few paragraphs on Indian food can hardly do the subject justice. Northern Indian cuisine varies greatly from southern Indian; some areas use oil, others ghee; some use rice, others breads; and some groups are vegetarian while others are meat eaters. More interestingly, each region uses spices most appropriate for its weather, because some spices cool the body and others are warming, thus nurturing the body and the spirit at the same time. This cool versus warm property of spices is one of the principles of ayurvedic medicine.

Traditional Indian Savories (Namkiin)

The foods most commonly served with chais are savories, of which there are literally hundreds of variations; I can only describe a few of them here. Chai is the perfect balance for these often quite hot savories made with chilis, heavy doses of garam masala, plus additional spices.

Most savories are not, however, for the calorie or time conscious, because many are deep-fried to be served immediately after cooking. Fortunately, many Indian grocers have frozen interpretations that you can simply thaw and fry at home, a great time saver. Some brands can be heated in the microwave for the best of both worlds — no prep and no frying.

Sev

6 servings

This marvelous snack uses a special tool called a sev mold that’s like a large garlic press. If your local Indian grocer doesn’t have one, you can form chunky strips by hand or use a grinder set on large holes to achieve the same shapes, or use a spaetzle press.

Ingredients

- 21⁄2 cups gram or besan (chickpea) flour

- 1⁄2 teaspoon chili powder

- 1⁄2 teaspoon asafetida (hing)

- 1⁄2 teaspoon ajwain (omum)

- Canola oil, as necessary

- Salt, to taste

Instructions

- 1. Mix the gram or besan flour, chili powder, asafetida, ajwain, and a little heated canola oil, about 1⁄2 teaspoon. Add enough water to form into a stiff but smooth dough. Knead well.

- 2. Divide into small portions (about 1-inch) and reserve.

- 3. Heat about 1 tablespoon of canola oil in a deep frying pan. When a drop of water sizzles when dripped into the oil, you’re ready to add the dough.

- 4. Place a portion of dough in a sev mold, hold the mold over the hot oil, and press carefully until the entire dough portion is passed through the sieves at the base of the mold. Let the sev fall gently into the hot oil, frying one portion at a time.

- 5. Using a wooden spoon, move the pieces of sev dough in a circular motion. Turn and fry the sev till golden and crisp, taking care not to burn them.

- 6. Drain and place on paper towels or kraft paper. Cool and store in an airtight container.

Koftas

2 servings

These spicy meatballs are to Indian cuisine what Swedish meatballs are to Scandinavian cuisine, but spicier, more flavorful, and, I think, infinitely more interesting. They go well with rice. This recipe can easily be doubled or tripled.

Ingredients

- 16 whole raw almonds

- 1⁄2 pound lean ground lamb

- 1 large egg

- 1⁄4 teaspoon salt

- 1⁄8 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

- 3 tablespoons gram or besan (chickpea) flour

- 1 tablespoon spring water

- 1 cup canola oil, for frying

- 1⁄4 cup ghee (Indian-style clarified butter)

- 1⁄4 cup finely chopped onion

- 1⁄2 teaspoon finely chopped garlic

- 1⁄2 tablespoon chopped fresh ginger

- 1⁄4 teaspoon ground turmeric

- 1⁄4 teaspoon ground cumin

- 1⁄4 teaspoon ground coriander

- 1⁄8 teaspoon ground hot pepper, e.g. cayenne

- 1⁄2 cup plain yogurt, drained and thickened

- 1⁄2 teaspoon garam masala spices

- 1 tablespoon finely chopped fresh coriander (aka cilantro or Chinese parsley)

Instructions

- 1. Soak the almonds in boiling water to cover for about 2 hours; drain and discard the water.

- 2. In a large bowl, combine the lamb, egg, salt, and pepper with 11⁄2 tablespoons of the chickpea flour. Knead with your hands then beat with a wooden spoon until smooth and well integrated.

- 3. Divide the mixture into eight equal portions. Shape each into a flat round, place an almond in the center, and enclose the meat around the nut until you have a ball shape.

- 4. In a separate bowl, make a batter with the remaining chickpea flour and the water. Spread the batter evenly on all sides of the meatballs (your fingers are fine) and place them side by side on a piece of wax paper.

- 5. Using a wok or deep fryer, heat the canola oil to at least 375˚F and deep-fry about three or four meatballs at a time, turning them with a slotted spoon over and over until they brown. As each meatball completely browns, transfer it to a plate covered with a paper towel or Kraft paper, to absorb additional oil. Repeat until all the meatballs are cooked.

- 6. In another pan, heat the ghee until hot; add the onion, garlic, and ginger and cook lightly for about 2 minutes. Add the turmeric, cumin, coriander, and hot pepper and stir constantly for about 10 minutes or until the onion is golden. Stir in the yogurt, mixing thoroughly.

- 7. Spoon in the meatballs until they are thoroughly covered with the onion mixture, then sprinkle the garam masala spices over everything. Cover the pan tightly, reduce the heat to low, and simmer for about 10 more minutes.

- 8. Remove from the heat and let the mixture rest for about 1 hour (do not remove the lid). To serve, simmer gently for just 5 minutes, then pour onto a deep platter and garnish with the fresh coriander.

Samosas

Serves 12 people as appetizers, 6 as a part of a meal

These scrumptious deep-fried pasties can be filled with vegetables or meat. Every household has its own recipe; here’s one to whet your appetite and tempt your culinary skills. These are an ideal way to make a treat from yesterday’s leftovers. Flavored chutneys or salsas taste wonderful with them, plus your favorite milky chai.

Ingredients

- Pastry Dough

- 3⁄4 cup all-purpose white flour

- 1⁄2 teaspoon salt

- 1⁄2 teaspoon unsalted butter, melted

- 3⁄4 cup milk less 1 tablespoon, warmed but not boiled

- Corn or canola oil, for frying

Instructions

- 1. To make the pastry dough, sift the flour and salt into a mixing bowl. Make a well in the middle of the flour and add 1⁄2 teaspoon of butter and the milk. Mix well and knead into a stiff dough. Cover with a damp linen cloth and set aside in a warm spot.

- 2. To make the samosa stuffing, melt the 2 tablespoons of butter in a medium size frying pan. Fry the onion until it’s cooked but not browned. Add the remaining stuffing ingredients and mix well. Cook, stirring frequently, until the mixture has absorbed the butter and is dry. Remove from the heat and let cool, uncovered.

- 3. Cut the dough into quarters, and divide each quarter into six parts. Roll each out into a thin round.

- 4. In the center of each round, place a spoonful of filling. To fold, dampen the edges of the dough with milk and fold into a half circle (like a mini empanada or turnover). Press the edges together, crimping them like the edges of a piecrust. The most popular samosa shape is a pyramid.

- 5. Heat about a tablespoon of oil in a frying pan until a drop of water spatters, then slowly and carefully lay the samosas in the pan with a spatula, turning them several times until golden brown.

- 6. Remove and drain well on Kraft paper or paper towels. Repeat until all of the samosas are done. Serve immediately while hot.

Pakoras

Makes about 3 dozen small pancakes, enough for 12 people for appetizers or 6 people as a side dish with a meal, along with your favorite chai

These delicious Indian savories are deep-fried vegetable fritters, rolled with flour to make a fried dumpling rather than stuffed inside a dough covering like samosas. They’re spicier, too, with the use of chili powder, cayenne, and fresh chilis. Dried chilis can be substituted for fresh. This is indeed a strong-tasting dish, so feel free to reduce the cayenne to a pinch and the chili powder to perhaps 1 teaspoon.

Pakoras taste delicious with a mango-tomato salsa or a mango chutney. Bottled chutneys are widely available on the condiment shelves of grocery stores. To make a mango salsa, add 1 chopped fresh mango to 1 cup of chunky tomato salsa; mix in about 1 teaspoon of chopped fresh cilantro and salt to taste. The sweetness of the mango cuts the sharpness of the tomatoes, and the “yin-yang” of it all is wonderful with Indian savories. Papayas can be substituted for mangoes.

Ingredients

- 3⁄4 cup grated fresh cauliflower or broccoli, drained of excess moisture

- 1 fresh red chili, chopped (Mexican or Indian, as available)

- 1 large yellow onion, minced

- 1 teaspoon ground cayenne pepper

- 1 teaspoon garam masala spice mix

- 2 teaspoons chili powder

- 2 teaspoons salt

- 1 teaspoon ground turmeric

- 1 tablespoon chopped fresh cilantro

- 3⁄4 cup all-purpose wheat flour

- 3⁄4 cup ground rice powder

- 1 ounce fine semolina

- Cold water, about 1⁄4 cup or more as needed

- Canola or corn oil, for frying

Instructions

- 1. Mix the vegetables, chili, and onion with the spices and dry ingredients. Slowly add enough cold water to form a thick batter.

- 2. Heat the oil in a pan until a drop of water spatters when dripped into the oil. With a large tablespoon, drop spoonfuls of the batter gently into the hot oil. Flatten each slightly into a small pancake. Fry until golden brown and crisp. Try to turn only once.

- 3. Remove from the pan and drain well on Kraft paper or paper towels. Repeat until all the pancakes are done. Serve immediately while hot.

Barfi

24 pieces

This Indian “fudge” is available in a light brown or bright green pistachio (pista) flavor, or a dark brown almond (badam) flavor. It’s very sugary sweet with a crumbly texture and fudgelike consistency. The following is an almond and pistachio barfi that is perfect for a chai made without milk or sugar. The spiciness of the tea beautifully balances the sweetness of the barfi.

Ingredients

- 1 cup slivered blanched almonds

- 1 cup unsalted pistachios

- 4 teaspoons ghee (Indian-style clarified butter)

- 1 quart whole milk

- 1 cup sugar

- 1⁄2 teaspoon pure almond extract

Instructions

- 1. Pulverize the nuts in a grinder or blender until they are a smooth powder. Set aside.

- 2. Spread about 1 teaspoon of the ghee over a 71⁄2-inch pie tin using a pastry brush or wax paper.

- 3. Bring the milk to a boil in a heavy saucepan over high heat. Reduce the heat to medium and continue cooking the milk, stirring frequently, until it thickens to the consistency of a heavy cream (about 30 minutes). Slowly pour in the sugar and stir for an additional 10 minutes.

- 4. Slowly add the nut powder and cook for 10 minutes more, stirring continuously. Add the remaining ghee and cook for about 7 minutes, stirring until thick enough to form a solid mass.

- 5. Remove from heat and stir in almond extract. Carefully pour the mixture into the pie tin, smoothing it with a rubber spatula.

- 6. Allow to cool for about 30 minutes. Cut the barfi into triangles or diamonds at this point, because it will harden as it cools further and will become difficult to cut.

Carrot Halwa

4 servings

A favorite of the Sikhs of Punjab, carrot halwa originated from nut dishes introduced by traders from the Middle East and Asia Minor during the Moghul period. Indians have used a variety of vegetables for halwa, including pumpkins, zucchinis and other squashes, potatoes and yams, and even winter melons. Some recipes substitute ricotta cheese and dry milk for the whole milk used here, but I believe fresh milk produces a richer and smoother sweet. Halwa can be kept refrigerated for several days, then heated prior to serving.

Ingredients

- 3 medium carrots (about 1⁄2 pound), scraped and coarsely grated

- 1 quart whole milk

- 1⁄2 cup light cream

- 1⁄2 cup dark brown sugar, packed, mixed with 1 teaspoon dark molasses

- 1⁄4 cup granulated sugar

- 3⁄4 cup whole blanched unsalted almonds, pulverized in a grinder or blender

- 2 tablespoons ghee (Indian-style clarified butter)

- 1⁄2 teaspoon cardamom seeds, crushed

- 2 tablespoons unsalted roasted pistachio nuts

- 2 tablespoons unsalted, slivered, blanched almonds, toasted

Instructions

- 1. In a heavy saucepan, combine the carrots, milk, and cream and bring to a boil over high heat, stirring continuously.

- 2. Reduce the heat to moderate and cook for 1 hour, stirring frequently, until the mixture has been reduced by half and coats a wooden spoon thickly.

- 3. Stir in the brown sugar, molasses, and granulated sugar and cook for 10 minutes. Reduce the heat to its lowest setting, add the ground almonds and ghee, and stir for 10 more minutes or until thick enough to form a heavy mass.

- 4. Remove from the heat and stir in the cardamom seeds. Spread the halwa on a heatproof platter and decorate with pistachios and slivered almonds. Serve at room temperature, or warm.

Jalebis

60 jalebis

These are Indian doughnuts, crisp, deep-fried batter immersed in a rose water-infused syrup. Prepare the batter the day before, because it must rest for 12 hours.

Ingredients

- 2 cups lukewarm water (110–115˚F)

- 1⁄4 teaspoon double-acting baking powder

- 1⁄4 cup rice flour

- 3 cups all-purpose white flour

- 4 cups sugar

- 3 cups cold water

- 1⁄8 teaspoon cream of tartar

- 2 teaspoons yellow food coloring

- 1⁄8 teaspoon red food coloring

- 1 teaspoon rose water

- 3 cups canola oil

Instructions

- 1. Combine the warm water, baking powder, rice flour, and all-purpose flour into a smooth batter. Allow the batter to rest at room temperature, uncovered, for 12 hours or overnight.

- 2. When the batter has finished resting, combine the sugar, cold water, and cream of tartar in a deep saucepan and stir over moderate heat until the sugar dissolves. Increase the heat to high. Bring the mixture to a boil then let it cook, undisturbed, for 5 additional minutes. Its temperature should reach 220˚F on a candy thermometer.

- 3. Remove from the heat and stir in the food colorings and rose water. Pour the syrup into a bowl and set aside.

- 4. Pour the canola oil into a deep fryer or large wok and heat to 350˚F. The tricky part is shaping the jalebis. Use a pastry bag filled with about 1 cup of batter at a time, and squeeze it directly into the hot oil, drawing lines back and forth several times to form a pretzel of figure-eights or lines; the shapes are certainly up to your creative bent, but each jalebi should be about 2 by 3 inches if it’s to fry quickly and easily. Fry four or five jalebis at a time for 2 minutes or until golden on both sides. When done, transfer to the syrup to coat for a minute, then transfer to a warm plate. Repeat until all the batter is cooked.

Classic Indian Condiments

The cuisine of India is as complex, as exciting, as varied as its languages, religions, and people. There are, however, a few foods that are used in nearly every region. The first is a combination of spices called garam masala. A clarified butter known as ghee is used extensively as are onions by the bushelful. What follows are “must-use” condiments every Indian cook must learn to make.

Ghee

11⁄2 cups

This Indian-style clarified butter is an oil made by cooking butter long enough to clear it of its fat and enhance its flavor to an almost nutty taste. Simple clarified butter is not the same thing.

Ingredients

Instructions

- 1. Melt butter in a heavy saucepan over moderate heat without letting it brown.

- 2. Increase the heat and bring the butter to a boil until its surface is covered with white foam.

- 3. Reduce the heat and simmer, uncovered, for about 45 minutes, or until the milk solids on the bottom are a golden brown and the butter on top is transparent.

- 4. Remove from the heat and pour through a fine sieve or dampened cheesecloth into a large bowl. Re-strain as often as necessary; even tiny pieces of solids will turn the ghee rancid.

- 5. Pour the perfectly clear ghee into a jar, cover tightly, and store in the refrigerator. Simply reheat over a low flame.

Garam Masala

11⁄4 cups

This blend of spices is typical of a dry masala used in cooking. By adding coconut or other “wet” ingredients, you can achieve a wet masala. With variations, this mixture can be used to make Indian spice tea or milky chai, or added to any food item in which you want the taste of chai. The amounts here are on the spicy side, so adjust according to your taste. This blend will keep for months in a jar with a tight lid, stored in a cool, dark cupboard.

Ingredients

- 1 cup whole green cardamom pods

- 1⁄2 cup whole cloves

- 1⁄2 cup whole cumin seeds

- 1⁄2 cup whole black peppercorns

- 1⁄4 cup whole coriander seeds

- 5 3-inch pieces of cinnamon stick

Instructions

- 1. Preheat the oven to 200˚F.

- 2. In a large, shallow roasting pan, spread a layer of the spices. Roast them in the oven for about 30 minutes, avoid over-browning or burning.

- 3. Remove the pan from the oven and allow the seeds to cool. Open each cardamom pod, pull the pod from the seeds, and discard. Set the seeds aside. When cool, immediately pour into a jar, tighten the lid securely, and store in a cool, dark place.

- 4. Crush the cinnamon sticks by placing them between the folds of a plain-weave cotton towel and pounding with a meat mallet or rolling pin until finely crushed. A mortar and pestle can be used.

- 5. Combine all the spices until thoroughly mixed.

- 6. Grind the spices in an electric grinder or blender until they reach the consistency of a powder.

Paneer

4 cups

This is the most popular form of Indian cheese: soft, creamy, made with a whole milk that makes it just the right consistency for sweet dishes. Paneer is excellent with fruit or chai-flavored pastries like the scones on page 52 or with plain cookies. It can be refrigerated for up to two weeks between uses.

Ingredients

- 1 quart whole milk

- 1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice

Instructions

- 1. In a large saucepan, bring the milk to a boil over medium heat.

- 2. Remove the pan from the heat and add the lemon juice. Stir well until the curds and whey separate from each other.

- 3. Pour the entire contents of the saucepan through a piece of cheesecloth. Tie the cloth and squeeze out as much liquid as possible. If using a sieve, push a spatula onto the cheese until the liquid seeps out. Allow the cheese to continue to drain for at least 1 hour.

Chai Ros Malai

Quick “Indian” Cream

6 servings

This recipe from Chef Robert Wemischner is a delicious alternative to the Indian paneer that is the basis for many Indian desserts. Paneer is very time consuming to prepare, but this version takes a shortcut by using ricotta cheese. Here chai masala, augmented by some extra sweet spice, goes beyond the china cup to lend its haunting fragrance to the sauce for this dreamy cream.

Ingredients

- 1 pound ricotta cheese from whole or skim milk

- 4 cups whole milk

- 1⁄2 cup sugar

- 5 whole cardamom pods

- 1 cinnamon stick

- 4 whole cloves

- 2 tablespoons chai masala (or dry chai tea mix)

Instructions

- 1. Place the ricotta in a fine sieve set over a bowl to remove excess moisture. Refrigerate overnight, covered.

- 2. Make the creamy sauce by bringing the milk, sugar, spices, and chai masala to a boil in a medium saucepan. Cook, stirring frequently and deeply into the bottom of the pan, until the mixture has reduced enough to coat the back of a wooden spoon.

- 3. Remove the pan from the heat and pour the mixture through a fine sieve to remove its solids. Pour into a bowl and let cool. Refrigerate, covered, until cold.

- 4. To serve, pour a small amount of the sauce on each plate. Using two large soup spoons dipped in hot water, form the ricotta into oval-shaped portions. Center one ricotta oval on each plate and mask thoroughly with the remaining sauce.

A Traveler’s Tale

Our Journey Ends . . . or Does it? Kashmiri Tea

The air was unexpectedly hot, thick, unmoving — so unlike the familiar cool here in Sausalito, California. I sat for what seemed eons at the bus stop, my mind floating on waves of heat, when a little white car rolled in front of me. Thinking the driver wanted directions, I got up. A gentleman leaned over and asked in a heavy Indian accent if I was going to San Rafael.

“Come, I take you, it’s very hot today,” he said, the matter already settled in his mind.

My skirt and blouse seemed like velvet drapes, drenching me in sweat, next to the airy dance of his thin white clothing. The wind blew in through his window, inflating his gauze shirt and pants like billowing sheets hung out to dry. They were whiter than white against the darkness of his skin.

We chatted a few minutes about where he worked and where he lived. Then he asked what I did.

“I write,” I said.

“What do you write about?”

“Tea. Chai. I’m a chaiwallah.”

He smiled again and said, “Ah, chaiwallah, yes, you know about this,” his accent belying the ten years he had lived here. “Yes, oh yes, chai. I make very good Kashmiri chai, have you ever had this?”

With expansive hand gestures and great flourish, he revealed his own method: boiling the tea for at least an hour and a half, pouring hot water over the leaves many times during the cooking process, adding spices in just the right amount. “Time is very important, because the leaves are very big, the tea is, how you say?” he asked, tugging at my little finger. “Like this, very . . .”

“Thick? Hardy?” I asked.

“Yes, so that is why we cook it for such a long time, pouring water on it again and again. Many times you must do it so that it is just right. It is very good, my chai; it is a pleasure to drink all day long. In my country, we have every morning this chai. Special street vendors,” he started to explain.

“Chaiwallahs,” we said together. He turned and smiled, laughing lightly. “Yes, you know this very well. In my country,” he went on, “the chaiwallahs, they get up very early in the morning to make good chai for everyone to drink all day long.”

“Do you cook?” I asked.

“Yes. I’m a very good cook,” he said, lifting up his chin with pride. “Every time I cook, all the neighbors come by and ask, ‘What is that wonderful smell? What are you cooking?’ It is not hard, this cooking, but it takes much time.”

The cars beside us became a kaleidoscope of colors as he sped along, telling me how Indian dancers and musicians had entertained at the recent street fair in San Rafael. “Americans, they seem to like Indian music; I don’t know why. But they come every time to the fair to hear our music.”

“Do you play an instrument, are you a musician, too?” I asked.

“No, but I sing very well. Here, listen.” His pointed index finger signaled some unspoken downbeat. “I will show you.” He sat up with his back ramrod straight in his driver’s seat, his head facing forward more assuredly. His light baritone voice poured out a lilting Indian song. It went on for several choruses, ending when he turned and smiled as if to say, “It is true, I sing very well, yes?”

“Very lovely,” I said. I was about to ask him more when he tapped his forefinger on my hand and said, “Wait, wait, I’ll sing you another. Listen careful now,” like a father rewarding a child for good behavior. As he swayed his head from side to side, from out of his smiling lips came a haunting melody.

Touched by the sweetness, I whispered, “What does it mean, this song?”

He smiled knowingly. “Love is like a paper boat,” he explained. “Love is like a paper boat.” He moved his hands through the air in impersonation of a gliding boat. “It floats along the water, sometimes with the wind, and sometimes it sinks, because love is like a paper boat.”

He smiled again, showing his perfectly white teeth, the front ones considerably longer than the side, his smile beatific. He slowed down to a stop and said, “I’ll let you out here,” ending my reverie as abruptly as it began.

I hummed his melody all the way to work, unable to let it slip away. Tonight the melody returns to me, and for the first time, when the wind howls and rocks my floating home on the bay, my fears abate as the spicy aroma of Kashmiri chai wafts through my window.