Chapter 4

THE GOLD RUSH AND AFTER

Most estimates of California population at the time of annexation by the United States are just that. But rough figures put the European population at around 13,000–14,000. Even more difficult to arrive at is a population number for the native Indians. Their numbers had been in decline for years, decimated by the diseases carried by succeeding movements of Spanish, Mexican, European and American immigrants who were immune. But by the census of 1852, just four years after the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, California had 224,000 residents. The world had literally “rushed in” to become rich mining the gold fields of California.

This incredible immigration and the massive changes that it brought have been well studied by historians. Social and legal institutions in the new state struggled and failed to cope. But a freewheeling economy developed out of the chaos. Those economic opportunities for slaking the thirst of the hordes of miners in the gold fields of the Sierra Nevada were not lost on the winemakers of Los Angeles. Soon enough, they were making regular shipments to the markets of San Francisco and Sacramento. Not only wine and brandy but also fresh grapes went north. As Thomas Pinney succinctly says, “San Francisco was where the wine was drunk, but Los Angeles was where it was made.” This defined the relationship of the two sections of the state for decades, until the dominance of Los Angeles winemaking was equaled and then surpassed by the Bay Area wine regions in the latter nineteenth century.

The new arrivals from the East Coast and elsewhere who had experience in winemaking were astounded to see the thriving vineyards of Southern California. They were quick to see that the mild, dry climate with the fertile soil was almost perfect for viticulture. The centuries-long attempt at transplanting European vines to the American colonies on the East Coast, and then the new republic, had been met by repeated failure. Winemaking in the east was left with using the native labrusca and rupestris grapes, with their natural “foxiness” taste that was not to everyone’s satisfaction. Yet here in this new land were fields upon fields of vineyards with wineries making a wine of distinctively European taste, despite the flaws of the Mission grape itself and the unknowing and crude winemaking methods that were used. It wasn’t long before California was being touted as the “vineland of the world.”

Los Angeles had its share of population growth at this time, and not always for the better. Robbers, con artists, thieves and other morally bankrupt men from the mining areas up north made their way to the southern part of the state to set up their brand of “money-making.” The crime rate in Los Angeles shot up in the 1850s. At one point, the town had a murder a day, according to historian Nat Read, in a population of not even 1,700. As Read points out in comparison, the Los Angeles crime statistics for 2006 (his book’s date) had approximately the same murder rate (one a day) but in a population of over 3 million. At that 1850s per capita rate, one would think that the town would be depopulated in no time. But the continuing supply of drifters from all areas belied that possibility. For a while, Los Angeles’ violent notoriety was unsurpassed. Even the celebrated “Wild West” towns of Dodge City, Abilene and Deadwood weren’t this bad. In the morning, Angelenos would ask one another who got shot/knifed/murdered the night before.

One new Angeleno from Germany wrote a memoir of his early days in the pueblo, Sixty Years in Los Angeles, which has become a basic reference for what is known about the time period. Harris Newmark arrived in Los Angeles in 1853, where he became a store owner, trader and freight hauler. He made a fortune in real estate dealings. When he arrived, he found more than one hundred vineyards in the general area and seventy-five to eighty within the town itself.

MATHEW KELLER (1811–1881)

Mathew Keller came to Los Angeles in 1851 after a long stay in Mexico. He was already known as “Don Mateo” from those years and easily fit in to the daily life of the still Spanish-speaking pueblo. Across the river was his good friend from the Mexico days, fellow Irishman, brother-in-law and vintner, Andrew Boyle. It didn’t take long for Keller to rival Wolfskill and the Sainsevains in wine production. He built a home and winery at Alameda and Aliso Streets, with his first vineyard (twenty acres, with supposedly fifty-year-old vines, according to biographer Dinkelspiel) toward the river. He was constantly buying and planting new vineyards, famous for importing new grape varieties, and wrote a treatise on Los Angeles winegrowing in 1858 (Appendix 3). That report was sent to the U.S. patent office, along with a select bunch of grapes from his vineyards (that may have been a touch of his Irish humor; what condition were the grapes in upon arrival?). As at most other vineyards, the hard work at Keller’s vineyard was done by the native Indians, many trained years ago at the missions. Keller appreciated their “art” with the vines. His large vineyard—150 acres—to the south of town was Rising Sun Vineyard, where he planted Malvoisie grapes as well as the ubiquitous Mission. Keller bought the Rancho Topanga-Malibu-Sequit, with its twenty-three miles of spectacular coastline, in the early 1870s (for ten cents an acre). The primary occupation was cattle ranching, but he began planting vines there (what he called Malaga Ranch, just above Santa Monica) a few years before his death, to the tune of five hundred acres.

Though he had become quite wealthy from his wine business (he was known as the “wine-making millionaire”), the national downturn in the economy during the 1870s coupled with accusations of poor quality of his wines substantially affected his income. He went to New York in 1877 to act as his own agent, writing that he went “to save my property and to get out of the wine business—and to do this I have risked my life in my old age in New York in the depth of winter to try and accomplish it…The wine business has been a millstone around my neck…It has swallowed up all I made on land sales and any other way.” This was quoted by historian Thomas Pinney. His close friend in Los Angeles, the young German-Jewish shopkeeper turned banker Isaias W. Hellman, advanced him the money for his New York venture and maintained his business interests at home while he was away. In a few years, Keller was solvent once again and returned to Los Angeles.

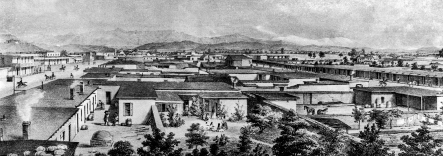

Kuchel and Dresel illustration of Los Angeles in 1857, view north and east. The large tree on the far right edge of the view is J.L. Vignes’s El Aliso. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Keller was an original investor and stockholder of the Farmers and Merchants Bank of Los Angeles, which was under the direction of Hellman. As a mark of his friendship and trust in the man, Keller appointed Hellman as executor of his will and guardian of his four children. Though Keller died in 1881, his estate wasn’t settled until 1886, when all the children had reached their maturity (a stipulation of the will). For his probity, sagacity and honorable handling of his friend’s estate, Hellman was universally commended.

KOHLER AND FROHLING

The chaotic growth of the wine trade in Los Angeles needed an organizing hand from the merchants’ point of view, someone who could pull the disparate parts together and efficiently get the wine to the market in San Francisco and the gold fields. Two men played a key part in satisfying this need, and neither had any previous experience in winemaking, grape growing or business, nor had they even seen a vineyard. Charles Kohler, a violinist, and his musician friend John Frohling, a flutist, had both come to San Francisco in 1853 from their homes in Germany. Both met from their involvement in the Germania Concert Society, established to bring a sense of culture to the raw frontier town. But they could see that there was a great opportunity in the wine trade. Pooling their resources, they bought a vineyard in Los Angeles in May and harvested a first crop in the fall of 1854, with hired German help. Their first few hundred gallons sold out to their German and French clientele. As the Americans caught on, their business grew by leaps and bounds. Dividing their responsibilities, Kohler remained in San Francisco as the salesman and organizer. Frohling went to Los Angeles to oversee the growing, harvesting and making of the wine. They were good at what they did, despite their inexperience. They bought grapes from every grower in town, with Frohling bringing his own crews to do the harvesting and crushing, which was fast and efficient. His winemaking methods and standards were far and away superior to what was being practiced at the time. By 1859, they were dominating the market in the pueblo, searching for whatever stock they could obtain. In that year, they made more than 100,000 gallons. The next year, they made so much they had to rent out additional space in the basement of the city hall. In 1861, they sent 130,000 gallons north. The Kohler and Frohling Co.’s appetite for more grapes to satisfy its market led directly to the founding of the Anaheim colony.

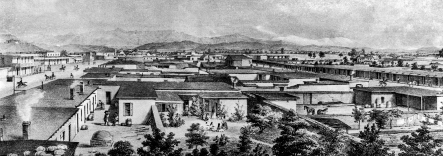

Kohler and Frohling’s winery building on Main Street, circa 1857. From the Kuchler and Dresel illustration of the same year. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.

The company’s next focus was opening an agency in New York. By 1860, it was doing so. It could not have been easy. With no road or train across the continent, sailing around the Horn of South America was the only way. Aging wine on a long ocean journey, however, was a tried-and-true method. The Sainsevain brothers also opened a New York branch in 1861. In this period, wine tastings in New York that advertised California wines were in actuality tasting Los Angeles wine, so dominant were the town’s vineyards and winemakers. Shipments to New York and the eastern cities continued to rise. By 1867, 150,000 gallons of Los Angeles port, 80,000 gallons of Angelica (the Los Angeles specialty: a sweet, white-wine liquor) and 500,000 gallons of white wine from Los Angeles and Sonoma were shipped from California. The range of their wines indicate how far they had progressed from the Mission grape.

Kohler and Frohling played a dominant role in the continuing development of the California wine business (a role they had essentially invented). Frohling had died rather early on in 1862, but Kohler kept his friend’s name on the business. When he died in 1887, he had helped change the state’s rustic wine commerce into an industry, foreseen the importance of the northern vineyards and helped the shift to those areas. Years before, he had been cheerily prophetic, saying, “On the long run we will beat Europe anyhow.” This amusing quote is from Thomas Pinney.

Angelenos were well aware of the importance and increasing prosperity of their wineries and vineyards. A grape motif made its way onto the original seal of the city, where it has remained in some form to this day. A short-lived newspaper appeared in the last years of the 1850s, the title of which implied this overarching influence: the Southern Vineyard. It was not a farmers’ newspaper and had a decidedly Democratic Party slant, says Newmark in Sixty Years in Los Angeles, though near its end it had become Unionist in its sympathies. It was ably edited by J.J. Warner, another vineyard owner and friend of Mathew Keller. Grapes and cattle were the prime occupations in Los Angeles in the 1860s, and from this source, other businesses thrived. A huge flood inundated the low-lying vineyards along the river in 1862, but in the years after that, a drought of long duration destroyed the Southern California cattle business. Wealthy men like Abel Stearns were ruined. Grape growing became more important than ever. Secretary of State William Seward visited Los Angeles in 1867 and gave a speech from the balcony of the Bella Union Hotel, the town’s main (and relatively grand but for the fleas) hostelry. He made many California references, each being met with a warm response. Lastly, when he said that he had seen the vineyards of Burgundy but that the vineyards of California far surpassed them all, he was met with a thunderous, long-lasting ovation.

Another early French wine company in Los Angeles was Vache Freres. Brothers Emile and Theophile Vache opened a winery on Aliso Street near Alameda in 1860. They had joined their uncle, also named Theophile, who had previously emigrated to California and, in the 1830s, had opened a small winery and vineyard near Hollister (or what was to be that city). A third brother, Adolphe, soon joined them. By the early 1880s, they could see that vineyards in the city center were being forced out by new industries. They bought land far to the east of town in an area they called Brookside (now Redlands) and planted a large vineyard, keeping their Los Angeles location for a while longer. Brookside Winery became a household name in the 1960s and ’70s, operated by the Vaches’ grandsons. Theophile II and Adolphe returned to France in their old age, a habit many other French émigrés imitated. Emile stayed and is buried in Evergreen Cemetery in East Los Angeles, not far from his countryman and fellow winemaker Jean Louis Vignes. In the 1880s, Emile published a recipe for making Angelica, the sweet, white wine named for the town. A twenty-first-century winemaker found the recipe doing research and, with the old Mission grape vines she found on her property in the Santa Rita Hills AVA in Santa Barbara County, is now producing Angelica the Vache way.

Pelanconi house on Olvera Street (Calle de la Vina/Vine Street until 1877) had been the winery building of an early Italian immigrant winemaker, Giuseppe Gazza, who came to Los Angeles in the Mexican period. His partner was another Giuseppe—Giuseppe Covaccichi—whose Italianized name masked his Croatian origins on the Dalmatian coast of the Adriatic. Antonio Pelanconi, from Lombardy in northern Italy, arrived in 1853 and began working for the two Giuseppes, ultimately taking over the business and buying the building that bears his name. He married Isabel Ramirez, sister of an early vineyard owner and neighbor. Their son Lorenzo carried on the winemaking business, only giving it up to his mother and her new husband in 1877 so he could concentrate on grape growing in his large vineyard north of town. At the great curve of the Los Angeles River, just north and east of Verdugo Creek’s outfall, he planted his grapes on land where Jose Maria Verdugo very possibly planted his first vineyard of San Gabriel mission vine cuttings sometime in the 1790s. Pre- and postwar housing now cover the vineyard, but the area is known as the Pelanconi neighborhood, with a park and street that commemorate the name.

The railroad that connected Los Angeles with San Francisco in 1876 increased the tempo of changes in the old pueblo that began with the American occupation. It took the easiest route into the town: along the farmland next to the river—the prime vineyard land. As the vineyards and gardens began to go, so did the old zanja water system that irrigated them. New water pipes began to be installed, providing cleaner water to new homes and businesses. The old live willow tree fences that shaded narrow lanes were pulled out for housing and commercial uses. The once green swath that indicated the pueblo to approaching travelers out on the plain was decidedly less so. Vining plants that decorated flat-roofed verandahs on adobes disappeared when new, larger buildings took their place. With those flowering plants gone, the smells on the air changed as well. American-defined progress was arriving with each train.

Map of the Los Angeles area from San Fernando to San Juan Capistrano, the “Southern Vineyard.” Map by the author.