Chapter 8

DECLINE IN THE SOUTH

The 1880s opened with the southern vineyards overtaken by the north in vineyard plantings and wine production. The seven Bay Area counties, where the main growth was occurring, were together slightly one-third more in land size than the single Los Angeles County (which still included what would become Orange County) in the south—the prime growing area. Los Angeles was still adding vineyards and opening new wineries, just not at the same explosive rate as the north. At this time, the Central Valley was also planting vineyards at a rapid rate, whose aggregate acreage—more than fifty years later—would dwarf both the north and the south.

The newly formed Board of Viticultural Commissioners included two members from the south: James De Barth Shorb, member at large, and L.J. Rose, representing the southern district. The other representatives of the eight-member board were dominated by northern interests, especially by its president, Arpad Haraszthy (son of the indefatigable Agoston), and Charles Wetmore, the board’s own dynamo and public face.

In Los Angeles, new immigrant winemakers—especially from Italy—continued to maintain the very diverse lot that was the original. Giovanni Piuma arrived at this time, opening a winery on Main Street near the Plaza that only closed in the 1940s. He had vineyards in the El Monte area. The De Mateis family had a winery in the older section of Los Angeles and vineyards in San Gabriel and later in Cucamonga.

Just to the south of downtown, Remi Nadeau, a former mayor of Los Angeles, bought land in the area known as Florence. A French-Canadian, he had made a fortune as a freight hauler and investor in eastern California silver mines. In the early 1880s, he began planting two thousand acres of vines, including the (de riguer) Mission, Malvoisie and the ever-popular Zinfandel. He built a large winery complex but committed suicide in 1887 at the height of the land boom. The housing tract mania of that time rolled over his vineyards. His name is remembered in the area with Nadeau Street.

GEORGES LE MESNAGER

Georges Le Mesnager and his business partner Pierre Durancette were in the wholesale liquor and wine business in the early 1880s when they built their first winery, Sunny Side, at Second and Los Angeles Streets. Le Mesnager (difficult for American tongues past and present to pronounce: some say Luh Mess-na-shay, others Luh Mezz-na zhay or Luh Menna-zhay) had come from Mayenne, France, where his family owned vineyards. He arrived in Los Angeles (by certain accounts) in 1866. He most likely worked for the winery of his countrymen, Vache Freres, on Alameda, as he very prominently invoked its name in his later advertising. Later, the Vache brothers moved east and opened the Brookside Winery (in what is now Redlands), at the same time as Le Mesnager’s new Sunny Side Winery was opening (Le Mesnager had several wineries under a variety of names). When the Franco-Prussian War broke out in 1870, Le Mesnager went back to fight for France, becoming a color-bearer. A patriotic Frenchman despite his long life in Los Angeles, he vowed to fight again for France should the need arise. He became prominent in the French community of Los Angeles, edited a French-language newspaper and gave a fiery speech (in French, of course) at the centennial celebration of the French revolution in 1889. He felt that France needed him again in 1914, and he returned to his home country to become famous as the oldest soldier in the French army (either sixty-four or seventy, depending on birthdate believed). He was wounded, returned to Los Angeles and then went back again to France as a liaison officer on General Pershing’s staff. He returned once more to Los Angeles and finally back to his boyhood home, where he died in 1923.

In 1883, he was advertising for all sorts of wine bottles at the corner of Los Angeles and Commercial Streets. In the same year and same location, he later advertised that he had on hand over 100,000 gallons of wine of all types. He invoked Vache Freres and mentioned the “House established 1860,” the year that the Vaches opened their first winery. Georges would use that year repeatedly on his stationery.

Letterhead/invoice of Le Mesnager Winery on North Main Street, Los Angeles, using the signature “Old Hermitage” brand. Some of the letterheads included “successors to Vache Brothers.” The 1860 date implies that reference to the start of the Vache winery. Courtesy Historical Society of the Crescenta Valley.

As a winemaker in Los Angeles, he (and his partner, Pierre, who evidently was very low key, compared to the effervescent, boastful Georges) began buying vineyard property, primarily in the northern part of Verdugo Canyon. There is some evidence that he purchased a vineyard from the Sainsevains in what is now Rialto in the Cucmonga area. In 1886, he purchased over 700 acres on the high slopes of the San Gabriel Mountains at the mouth of Dunsmore Canyon in La Crescenta. He now had reportedly almost 1,300 acres in vines in the Verdugo/La Crescenta area. Later, the Le Mesnagers were joined by other winemakers, making the old Rancho La Canada lands filled with small-property vineyards.

In 1893, his business was raided by Los Angeles tax collectors for not paying his liquor taxes and letting his liquor license lapse. From a new winery site on North Main Street, his son Louis took over the business and continued making and selling wine. At one point, they owned Anacapa Island to run sheep.

Louis is the one who started developing the ranch buildings on the high La Crescenta property. He began building the stone barn in 1905. By a series of building “campaigns” of stone work, it was completed in 1915 and still exists. Louis managed other family vineyard properties. They had a way station building and corral on Glendale Boulevard in Glendale, the halfway point where the horses were watered and rested on the trek down from Dunsmore Canyon to the winery in Los Angeles with the wagonload of grapes. Vineyard planting continued ever higher and farther into the canyon. The lower part of the vineyard is at 2,200 to 2,500 feet elevation, while the flat “banks” of land along the creek in the farthest reaches of the canyon range between 2,700 and 3,000 feet. It was one of the higher-positioned vineyards around. Georges’s grandson Louis Jr. always maintained that his father’s best grapes were grown there. What they were is still a mystery.

View north to the San Gabriel Mountains of vineyards in the western La Canada valley about 1910. On the left is Lieutenant Governor Wallace’s castle, later notoriously known locally as the “Pink Castle” after the lieutenant governor’s angry wife painted it that color. Courtesy Glendale Public Library.

Jevne grocery store advertisement (circa 1898) in Los Angeles for La Crescenta wines. Hans Jevne was a Norwegian immigrant grocer who set up retail stores at the same time as George Ralph of present-day Ralph’s grocery stores. Courtesy Historical Society of the Crescenta Valley.

Another Crescenta/Canada ranching family was the Halls, who started a winery and planted vines in 1884. It turned into a sizeable operation when tourists in horses and buggies from the resort hotels in Pasadena started arriving for wine-tasting parties. Shipments to the east resulted. However, the main business was selling in bulk to Los Angeles wineries, which continued after the winery was closed down in 1904. Appropriately enough, the ranch was on Winery Canyon. Almost all of the far-flung vineyards in this high valley supplied the wineries and store owners in Los Angeles, even through the 1960s, when urbanization overwhelmed them.

JAMES DE BARTH SHORB

After the death of his father-in-law, Don Benito Wilson, Shorb seemed to put the wine business on hold, preferring bulk sales from his still-producing vineyards to merchants in San Francisco, such as Benjamin Dreyfus and others. Dreyfus, the dominating presence in the Anaheim wine area, also had an outlet in New York. He owned properties in Cucamonga and San Gabriel and had a large claim on the recently divided Rancho San Raphael of the Verdugo family. It was a natural thing for winemakers in the south to ship their wine by train in bulk to San Francisco for reshipment to the markets in the East. A direct rail link had not yet reached Los Angeles.

Bulk wine shipments were not without their cost. Shipping rates based on tonnage were coupled with taxes on wine shipments. If one could ship only the grape “must,” the tax could be avoided, and the weight of wine could be reduced by taking out the water, or so the reasoning went. Shorb jumped into this business (among many others) but found it bedeviling. It took precious time and money away from the project that was to dominate the rest of his life.

Shorb was planning a new winery project on a grand scale. He wanted to build an operation large enough to compete on the world market and solve some of the vexing problems of California winemaking in the process. The analysis leading to the formation of the San Gabriel Wine Company was sound enough: the vineyards of Europe were collapsing under the onslaught of the phylloxera vine disease and would soon be unable to supply their own demand; California vineyards had the capacity and quality (some said destiny) to fill that void; a company that controlled its product from vineyard to customer would solve the ubiquitous practices of fraudulent and adulterated wine sales; the company’s land in the valley (and elsewhere) would be far more valuable when the proposed railroad link connected Los Angeles directly to the east. This solid logic attracted a range of very prominent investors mainly from Britain (where Shorb had been attempting wine sales for years), as well as the powerful California banker Isaias Hellman (a friend and fellow vineyard owner). With a fine prospect for the future, and heavily financed (though with not as much money that was ultimately needed), the company opened for business in 1882.

Painting of the huge winery buildings in Alhambra, built by James Debarth Shorb for the San Gabriel Wine Co. Courtesy of the Alhambra Historical Society.

On its 1,500 acres, new vineyards were planted in each succeeding year, and arrangements were made to purchase grapes from surrounding vineyard owners (such as Sunny Slope, Hellman’s Cucamonga vineyards and the new vineyards of the Sierra Madre Vintage Co., for example). The new brick winery buildings being constructed in Shorb and Wilson’s new town of Alhambra had a fermenting capacity of 1.0 million gallons, with 1.5 million gallons of storage. But problems arose that worried investors. The sales end in the East had not yet been solved, and existing independent agents still had to be used. The company thought the majority of them were less than ethical. But many eastern merchants were dubious of the wine quality they were receiving, with some dismissing it as garbage. Both attitudes had some merit. The capability of the chief winemaker was in doubt. The company became more reliant on its land sales, which were spectacular in the land boom of 1886 through 1887. L.J. Rose of Sunny Slope took advantage of the rise in real estate prices and sold his vineyards and winery to more British investors in 1887. The winery buildings that Shorb constructed (entirely of brick) presented problems of their own, as the interior—over time—was too hot and dry. The wine quality suffered. The company’s indebtedness rose. Regardless, the sales kept climbing.

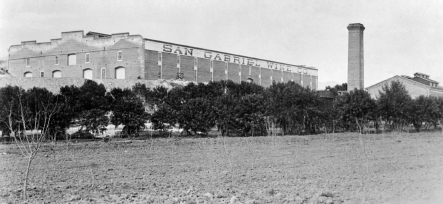

This 1880s photo shows the huge winery building for the San Gabriel Wine Co. in Alhambra. Courtesy of the Alhambra Historical Society.

Just as things began to look better, the Anaheim disease came to the San Gabriel Valley. Shorb was quick to take action, using his status as a Viticultural Commission member to hire botanists to arrive at a solution. That would take time, something the company did not have. Shorb resisted the notion of bankruptcy and began to plant oranges as a way to stave off insolvency. This angered Hellman, a major stockholder of the company, who insisted it be allowed to go out of business and the assets divided. The constant worry and the continual demands of all the other enterprises with which Shorb was involved caused his health to fail. His doctor brother in San Francisco and his wife pleaded with him to take better care of himself. In 1890, he was in a precarious state: about to lose his business and his health, and his wife’s inheritance from her father, Don Benito, was heavily mortgaged. In that year, he issued a report in his capacity as a Viticultural Commissioner on the Anaheim disease in the southern district: Anaheim was almost entirely wiped out; the San Gabriel valley had been seriously infected, but the disease was now passing; the Cucamonga valley and east had also been seriously affected, but there, too, the disease was rapidly passing; only the San Fernando valley was unaffected. Though the report was positive for future vineyard health (and perhaps somewhat disingenuous), news of the disease and the company’s heavy indebtedness made the sale of the San Gabriel Wine Co. almost impossible. The land boom had passed, and prices had fallen. The United States went into a financial panic in 1892–93, which hit hard at all the state’s winemakers.

Shorb and his wine company staggered along, selling what they could, often at “fire-sale prices.” He died in 1896 after being confined at home for some time. He was only fifty-four. His business expired a few years later. The company had in its great winery at dissolution nearly 150,000 gallons of wine (95,000 in port; 25,000 in sherry, amongst other wine varieties), and 50,000 gallons of brandy. It still owned 1,170 acres of land. Shorb’s attorney brother-in-law and neighbor, George Smith Patton, assisted in the breakup of the company. Hellman foreclosed on Shorb’s widow, Sue, in an 1899 court case. Afterward, she moved (with her children) to San Francisco. Shorb and his children are memorialized in street names, the only visible reminders in the town of Alhambra that he and Don Benito created. The huge winery buildings passed into other uses and were torn down in the 1980s. A Target store (almost as large as the winery buildings) occupies the spot at Main Street and Palm. A plaque placed near the entrance of the store by the Alhambra Historical Society commemorates the winery, the “largest in the world.”

James De Barth Shorb house south elevation, circa 1880s. Courtesy of the Alhambra Historical Society.

J. De Barth Shorb had been involved in so many pursuits and activities in the life of Southern California that it is difficult to describe. The ambition and energy that characterized his life had finally outstripped the ability of his health to accomplish them all. His personal legacy is the name “San Marino,” his grandfather’s plantation in Maryland. As legal heirs of the San Gabriel Wine Co., Hellman and George Smith Patton helped Henry Huntington to buy the vineyards and property in 1903. He had wanted to change the name to Los Robles but kept San Marino nevertheless. He built his own home soon after to house his growing art collection. Shorb’s Carpenter Gothic home was torn down, and the great Neoclassical “palace” that is there now took its place, with its unobstructed view over the huge vineyard that was the San Gabriel Valley. But the bold vision (similar to Haraszthy’s and others of similar character) of what the California wine industry could be is the true legacy of Shorb and his father-in-law, Don Benito.

THE END OF ANAHEIM

The disease that had infected the San Gabriel vineyards came from just a few miles south of the valley in Anaheim. By 1883, the German winemaking immigrants with their fifty wineries were producing more than one million gallons of wine a year. Their success had caused more vineyards to be planted in the near vicinity, with new, independent settlements growing wine and raisin grapes. Workers began noticing a curious change on the vines, especially the Mission. The leaves looked “scalded,” and the fruit would not ripen, withering in a soft mess. The next year, it happened again, only in an expanding area, and so on the next year. In its first years, the disease seemed not to have crippled the Anaheim vision of its future existence. Benjamin Dreyfus, the “wine king” of the area, felt confident enough to begin building a stone winery building, larger in capacity than any other in the neighborhood. But as the disease continued on its course, growers turned to the Board of Viticultural Commissioners for help, who hired a botanist to investigate and find a solution. The University of California got involved and began its testing, followed by the U.S. Agriculture department, the investigator of which was not particularly helpful. Regardless of that, the agency report estimated a $10 million loss for Anaheim and the Los Angeles area. The disease continued to spread, destroying almost all in its path, and no one seemed to know what it was or what to do. The agriculture department sent another investigator, Newton Pierce, who was much more methodical and scientific than the first, whose report appeared in 1891. He said that the “disease was none of those currently known, and that no remedies existed for it,” as quoted by Thomas Pinney. He suspected that it was a bacterium but couldn’t prove it with the methods and techniques of the day.

The disease was later named for him, and it is still a recurring problem today, especially in Southern California vineyards. By the time of Pierce’s report, the great experiment in Anaheim winemaking was gone, reduced to only a few acres of barely producing vines. The stone winery building of Benjamin Dreyfus remained empty of wine. It went on to other uses, partly torn down for a freeway project and then completely demolished in 1973. The German immigrants planted their decimated vineyards with groves of oranges and other citrus, which soon was even more widespread than the vines ever had been. They also turned completely to their breweries, which they always had; working in the vineyards is a thirsty business. In turning away from their winemaking roots toward another fruit crop, they made a future statement in 1889 by seceding from Los Angeles County and forming Orange County.

As if to put a finis on the decline, the great sycamore—the Aliso—that had stood for centuries beside the river, long before it had stood in the yard of Jean Louis Vignes’s winery, finally died. Before its end, the Philadelphia Brewery that had bought the land from the Sainsevains continued using the shade of the tree, too, for their customers’ ease in the hot sun. But as the brewery developed, the one-story wood-and-adobe buildings gave way to multistory brick ones that wrapped around the tree on three sides. It meant cutting off many of the tree’s limbs, weakening it in the process. After one branch fell and damaged some equipment, one of the brewery partners lopped off all the rest of the branches in a fit of pique. His other partner protested the desecration, but only a tall stump remained. By the end of 1892, it was dead. It remained in that condition until 1895, when an “experienced local axman” named William Willoughby chopped the tree down to be sold for firewood. The event drew a crowd, and people picked up chips and remnants as souvenirs of the ancient tree that had been a symbol for an era that had already changed beyond recognition.