The soma has been identified with many plants over the course of time. One thing is clear: the sap of the soma was inebriating. That substance was sensation: the one quantity that was quality. Everything depended on its being won or lost. There had been a time when even the gods didn’t have the soma. And they called it by another name: amṛta, the “immortal.” But they had yet to find it, to discover it, to touch the substance that was free from death, and that freed from death. All children of Prajāpati, though divided into the opposing ranks of the Devas and the Asuras, they agreed that for this once they could join forces, for this one undertaking, from which all others descend: the churning of the ocean.

The ocean seethed. The waves foamed like madmen in all directions as a vast pendulum plowed the waters. Torn from its roots, bristling with trees and sharp rocks, Mount Mandara thrashed the liquid mass like the beater in a churn. All the juices, the resins, the lymph of the plants flowed into the water along with liquid gold and cataracts of gems. All essences streamed together into the marine desert. Meanwhile the huge carcasses of deep-sea creatures hitherto unseen by any eye were driven up from the depths by the ceaseless motion of Mandara, who braced himself on the back of the giant turtle Akūpāra, the only creature to have remained impassive in the tumult. Looking closely, you could see a sash slithering around the lush grass of Mandara’s flanks. Or was it a thick rope? It was a snake, Vāsuki. With the Devas gripping its tail and the Asuras its head, it was being tugged back and forth to keep Mount Mandara churning beneath the waters, while from its mouth rose fumes that swirled around the Asuras and muddled their minds. But then it was they themselves, proud firstborn that they were, who had insisted on holding Vāsuki’s head, because the head is always the noblest part of anything.

“All this,” thought the Devas, “recalls the beginnings of tapas, that first friction in the mind from which every marvel is born.” But what was to appear this time? Or would anything appear? The Devas were exhausted. Like slaves at their oars, they held on to Vāsuki’s scales, just able to see in a steamy distance the grimaces of their eternal enemies, the Asuras, whom for this one undertaking they had accepted as allies. “When the stakes are high, one must be ready to make allies of one’s enemies, like the snake with the mouse,” Viṣṇu had exhorted. One must risk the ultimate, if one wants to gain the amṛta, the “immortal.”

At that time the Devas and Asuras were still too alike. Coarse, greedy, hot-tempered, their main ambition was to destroy each other. And to escape death. But death struck them down just the same. After each gory encounter with the Asuras, the Devas would count their corpses. They thought: “One day there’ll be none of us left to do the counting.” Then they were plunged into melancholy. And roused themselves in fury when their spies came to tell them what they had seen in the camp of the Asuras. There too the dead, many of them disfigured, were piled high under the vultures’ gaze. But then Kāvya Uśanas, chief priest of the Asuras, would come down and with a calm wave of the hand resurrect them one by one. To him, and to him alone, Rudra had one day imparted the saṃjīvanī vidyā, the “science of resurrection.” Thus the place teemed with Asuras. You couldn’t say they didn’t know death, because they were often killed and spent some time in death’s kingdom, suffering like anybody else, but then they came back to life, with no memory, no knowledge. They were merely shot through by a long and invisible wound: the enduring sensation of having already been killed. They suffered from that—but then they would laugh wildly when they looked toward the camp of the Devas, where the dead would never stand up and walk again. All the same, even the Asuras, who never died a final death, were eager to keep death at bay. Hence, and for just this once, they agreed to ally themselves with the Devas. Like their enemies, the Asuras were eager to conquer the amṛta.

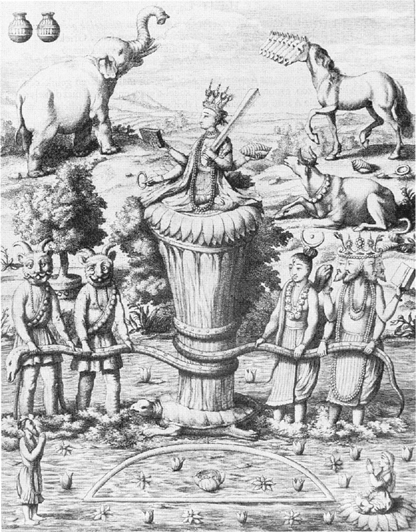

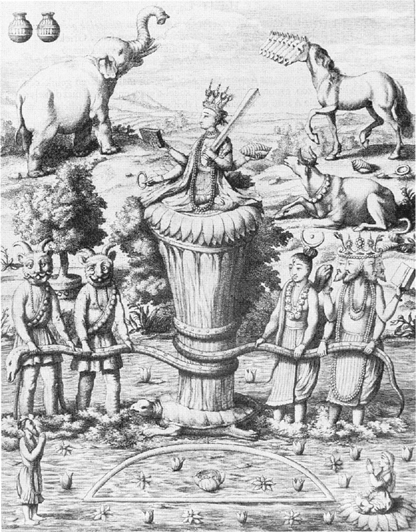

But here came the crucial uncertainty: would immortality become substance? The Devas and Asuras knew that they were involved in the first opus alchymicum. But what if their material were to remain opaque? What if the ocean did not yield up the “sweet wave”? Haggard and exhausted, they raised their eyes to find a splash of opalescence spreading out between Mount Mandara and the ocean. Suspended in the glow, like idols without pedestals, like actors who come forward one after another to greet the public, like bright rings in a bracelet, like painted figures on the breeze, like amulets strung across the torso of the cosmos, appeared the ratnas, the “gems,” sovereignty’s procession. First came Sun, then Moon—and then you could see the shadow of Śiva’s outstretched arm and hand encircling the white sickle like a slim girl and gathering it into his plaited hair, where it remains to this day, a shining clip. Next came the Apsaras, the waters, modeling the eddies in enchanting bodies dripping with shimmers of jewels. Both Devas and Asuras were equally avid for them, but they made no move: they knew that the Apsaras are living coinage, they pass through every hand. Not suitable as brides. Then came Uccaiḥśravas, the White Horse, swift as thought, who dazzled them with a toss of his mane. And there were more gems forming in the light. In white robes, fragrant and still, Śrī appeared majestic, then sank down on Viṣṇu’s breast.

But still the amṛta hadn’t appeared. The Devas and Asuras hung on, at the ready. “Perhaps,” they thought, “the world isn’t able, we aren’t able to distill that supreme essence.” Then a dark mass stood out against the glow, rolling like an ocean across the ocean. It was Kālakūta, the poison of the world. Viṣṇu spoke once more, his voice calm, and again his irony escaped those listening, as before when he had advised the Devas to join up with the Asuras, their all too kindred enemies. He said: “Śiva, supreme above all, yours is the beginning, yours the first fruit of everything. Only you can drink Kālakūta, the poison of the world, the first thing the world offers to us. Only he who can destroy the world can assimilate its poison. Only he who assimilates the poison of the world will have the strength of compassion.” Śiva answered: “My wish is to please you.”

Śiva bent down at the ocean shore, as the black mass began to lap around his feet. The Devas and Asuras watched, amazed, as though he were about to let himself be swallowed up by that unknown liquid. “This poison is born of the desire for immortality,” said a voice among them. Then they fell silent. Śiva plunged his left hand into Kālakūta, then raised it to his mouth, his face set in the expression of someone expecting delectable refreshment. He drank, swallowed, took the poison into his body, let it seep down and course through him like a secret river. The Devas and Asuras watched him, ever more amazed. An efflorescence formed on Śiva’s neck, like a tattoo, of a deep blue, whose brightness was reminiscent of a peacock feather or a sapphire. Śiva went on drinking, and the stain spread over his neck. Nor would it ever go away. They called him Nilakaṇtha, the Blue-Necked One. One day a blushing Pārvatī would confess that the first time she saw him—when she was still a solemn child—and Śiva turned toward her, so that she saw his neck, all her desire had concentrated on the tip of her tongue, which longed to lick that blue stain, even if it meant splitting in two, as the snake’s tongue did.

Like tarot figures upturned, the gems stood out against the column of light. The White Horse, the Precious Stone, the Nymph, the Elephant, the Physician, the Moon, the Cow of Desires. People still argue over how many there were and in what order they appeared. But one thing is certain: the amṛta could only appear within the procession of gems, within the sequence woven over the epiphanic veil. Nothing that appeared there was new or unheard of. Everything that emerged from the depths had emerged before. And yet everyone was amazed: because now existence was being formed, composed. With the churning of the ocean, the gems that have ever sparkled along the seams of existence were once again brought into being as second nature, elaborated, fixed, separate substance. The gods toiled like slaves in a smoke-filled workshop to have these emblems, seals of perennial existence, shine forth anew. “Elaborate the emblems and existence will follow,” such was their motto, and so it was. Then they left men to their own devices in the tangle of the existent world.

Last among the ratnas, the “immortal” liquid finally appeared. Gathering it in a cup, the gods’ Physician, Dhanvantari, offered it to the void. Among the Devas and Asuras, wonder soon gave way to apprehension, apprehension to avarice. Who was going to get it? Allies became enemies again. Petulant, childish voices were raised: “It’s mine, it’s mine …” Viṣṇu looked on, unsurprised. To head off another bloody battle between Devas and Asuras, perhaps even total reciprocal destruction—something that must not happen, since both the gods and their enemies are necessary to keep the world in equilibrium—Viṣṇu chose to resort to what had proved the most effective trick in his repertoire: turning himself into a woman. He became Mohinī: the Enchantress. Like a princess, like a courtesan, like a simple girl walking thoughtlessly by, Mohinī paraded before the Asuras, distracting them from whatever else was in their minds. Thus the Devas were able to grab the amṛta and take a quick drink before hurling themselves into the fray. Now they would slaughter each other as they always had. But soon they would be back in line again, invulnerable marionettes. The amṛta had made its entry on the world stage. The wiser of the Devas, however, felt it would be sensible if Viṣṇu took it under his care. Thus it disappeared once again, into the sky.

The stories of the soma tell of repeated conquest, repeated loss. Nothing is constant in its being but the soma itself. This applies to the gods too. Many have said that the gods are immortal and live in the sky. Not true. “Soma was in the sky and the gods here on earth.” The gods didn’t possess immortality. They thought of ways of getting it. They wanted to snatch the soma from the sky. Where was it hidden? In two golden cups, one upturned on the other, their sharp rims snapping shut at every blink of an eye. Flying across the skies came an eagle, Vāc, Word, sent by the gods. She tore the two cups apart with her beak, then sank her claws in the soft soma. But a Gandharva, Viśvāvasu, intercepted the eagle. Once again Soma eluded the gods. “We’ll never have eternal life without Soma.” “Soma was ours, all we have to do is buy it back,” they said. Vāc spoke up: “The Gandharvas are crazy about women. Give me to them in exchange for the soma.” The gods looked at her and said: “No, we could never live without you.” “It cost us dearly to win you from the Asuras. How could we live if we lost you again?” Calmly, Vāc answered: “Afterward, you could always buy me back again.” The gods fell silent. Then they nodded their agreement. Thus the gods assigned Vāc a second mission. She must seduce the Gandharvas, get them to forget the soma. But this time she wouldn’t need to be an eagle. All she had to do was to put on some makeup and the prettiest clothes she had.

The gods took Vāc to the borders of Gandharva country, like a group of suitors dating a dancing girl. They were in a daze from her perfume. But they thought: “The Gandharvas will be in even more of a daze than we are.” And others thought: “Perhaps it’s the last time we’ll ever see Vāc. We’ll be reduced to the same wretched creatures we were before. Why live at all, without Vāc and without Soma?”

Days went by. Then a delegation of Gandharvas suddenly turned up to speak to the gods. Normally carefree, cheeky, happy creatures, they seemed awkward, tormented. Almost unrecognizable. They began to speak with a solemn, uncertain tone: “You know that Vāc is among us.” Pause. “She has enchanted us all. With due respect we would like to ask if we might keep her.” The gods pretended a half smile of incredulity. “And what would we get in exchange? What could equal the worth of the most beautiful and enchanted of women, she whose bed lies in the waters, who bends Rudra’s bow, who pervades both earth and sky?” The Gandharvas lowered their eyes. Then one of them said softly: “Soma.” Apparently unimpressed, the gods accepted. “With her as a great naked one they bought Soma the King,” say the texts.

The Gandharvas were already walking away when one of the gods stopped them: “But what will you tell Vāc about this? You’re not planning to force her against her will … Vac has to be courted. At least let it be hers to decide who she wants to be with. Let’s invite her to a party …” The Gandharvas accepted. They thought they knew Vāc now. They prepared themselves with great determination, studying the Vedas. They would sing her the most sublime and difficult hymns in impeccable voices. And so they did, at the party. The splendidly handsome Gandharvas looked like austere brahmans. Their singing was pure and exact. Then it was the gods’ turn. They had used their time to invent the lute. They danced, they played, they sang, with a lightness and impudence no one had ever seen in them before. When they had finished, Vāc turned to them and smiled. She went back to the gods. The texts say: “That is why even today women are nothing but frivolity.”

Vāc: Voice, Word. Although eminent scholars hardly noticed her existence, Vāc was a power at the world’s beginning. Her place is in the waters, which she herself fashioned. An elegant woman, decked in gold, celestial buffalo, queen of the thousand syllables, fatal bride, mother of emotions and perfumes. Of the men she singles out Vāc says: “He whom I love, whoever it may be, I give him strength, I make him a brahman, a ṛṣi, a wise man.” There is no merit or virtue of any value in one whom Vāc has not singled out. He will forever be someone who looks without seeing. Since Vāc “knows all, but does not move all.” Guardian of inequality, she descends from above and touches only her chosen ones. Her help brings salvation. It was she who suggested she be bartered as a prostitute so that the gods could get back the soma. Quick to take offense, every intonation vibrant, her anger, should someone neglect her or prefer another, is terrible. Then she leaves the gods’ camp behind, but without going back to the Asuras. She wanders around the no-man’s-land between the two armies. Life dries up, things lose their shine. The word becomes treacherous to touch, to articulate. No one wants to speak. There’s a shadow in the undergrowth. No longer the painted woman with her gleaming jewels whom everyone desired, she approaches like a lean lioness, ready to tear her victims apart: that’s Vāc, now.

On the seventh day of the moonlit fortnight of March they met together where the Sarasvatī silts up in desert sands. They were setting off to celebrate a rite that was also a journey from which one might not return—from which some did not want to return. They headed east, against the flow of the Sarasvatī, because “the sky is against the flow.” And the place they hoped to reach was none other than the “bright world,” the svargaloka, the sky that once the gods had conquered. The light of that world opened out in a place called Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa, where the Sarasvatī came down to earth after her celestial journey, spreading out in ponds and meanders. Before setting off, they consecrated themselves to Vāc, to the Word, because “Sarasvatī is the Word and the Word is the way of the gods.” Traveling toward the source of the river, they would be traveling toward the source of the Word, whence it vibrates. “They go even to Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa; Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa is the furthest border of the Word; at the furthest border of the Word, there is the bright world.” They said to themselves: “The Word, Vāc, is the only way to reach the bright world. Vāc is Sarasvatī, this running river that silts up here, in our world, and loses itself. Setting out from this point, from the sands of our world, we must follow the river upstream. It is a long, hard undertaking, that goes against the way of things, which know only how to go down. The Word, and these waters, are the one help we have. We shall follow the Word, so as to be able to leave it behind. A mere span to the north of Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa, the Word is no more. Only something that shines. The center of the world.”

The gṛhapati, first among the celebrants and leader of the expedition, took a cart chock and hurled it as far away as he could. As he hurled it, he yelled, and the others yelled with him. They yelled and beat the ground, because “yell and blow are shows of strength”—and strength was something they needed. A herd of cows came after them, patient and silent. There might be ten, there might be a hundred. Where the chock fell they kindled the fire called gārhapatya. Then thirty-six paces to the east they prepared the fire āhavanīya. Thus for forty-eight days they walked along the banks of the Sarasvatī, sacrificing according to the phases of the moon, tossing the chock toward the east and stopping where it fell, yelling. That was their life: walking, yelling, “tribu prophétique aux prunelles ardentes.” Each time they stopped to sacrifice, they would take some of the sand left on the altar and carry it to the next place. A traveler who came across them without knowing anything of their ways would have thought them mad.

Walking upstream along the Sarasvatī was not without its dangers. Once, the daunting huntresses of the Śālvas attacked a group of celebrants and killed their gṛhapati, whose name was Sthūra. The others mourned him. But one of the celebrants saw their dead friend ascending to the sky along the line of their sacrificial fires. Another said: “Don’t weep for Sthūra. Whoever dies along this path ascends directly to the heavens. Don’t mourn these deaths. Once we were wretched, now the heavens await us.”

If they got as far as Plakṣa Prāsravaṇa, they would find a tree. At its feet rose the water that descends from the Milky Way, that is the Milky Way. The nearer one gets to that place, the more one feels the Word wear thin. “The breeze passes through the fabric,” thought the celebrants. The Word stretched thinner and thinner, to the limit. The more they sensed it, the closer they knew they were to the “bright world.” And, immediately beyond the point where the Word ended, they had reached their goal. But there were other ways the rite might be accomplished. One day they realized they had lost all they had. They woke—and the cows were gone. Stolen? Run off? Or the gṛhapati might die along the way. Perhaps he was killed in an enemy ambush. Or perhaps he just died on his feet. Even in these cases the rite had been accomplished. Or they might discover, one day, that the ten cows they had set out with were now a hundred. And again this might mean that the rite was accomplished. But whatever happened, when it was over, before returning to their lives so as not to go mad—“If he did not descend again to this world, he would either depart to a region which lies beyond all human beings, or he would go mad,” warned the Pāncavimśa Brāhmana—they bathed in a delightful bend of the Sarasvatī, in Kārapacava, just as Cyavana had immersed himself with the Aśvins in another meander of the Sarasvatī, rediscovering his youth.

Whether directly or indirectly, Indra’s adventures always had to do with the soma. God of entrenchment, of all that exists because made, mind muddied from his effort to fix the flux, Indra reigns, yes, but in the perennial fear that some force beyond might unsettle him, might take the cosmos back to the blessed and terrifying oscillation to which he put an end when he clipped the mountains’ wings.

It is thanks to Indra that the waters subsided, that the world doesn’t quake, isn’t forever swinging from side to side but supported by a prop that allows things to be distinct and have identity. He was the crudest and most ignorant of the gods, the only one who constructed himself, using the sva-, the prefix that signifies whatever is self-made. Indra had no science, no splendor. Only thrust, energy. He was often afraid when confronted by powers older than his own; he found them elusive. In his duel with Vṛtra, which was the ultimate purpose of his life, as well as the undertaking that would one day make it possible for all of us to live, he only won because when Vṛtra’s father, Tvaṣṭṛ, the Craftsman, had created that footless creature who slithered along stuffed with the soma he was born from, he, Tvaṣṭṛ, made a mistake pronouncing a word, got the stress wrong. Otherwise Indra would have been swallowed up. And the world would never have drawn breath. Who would have noticed? No one. Only when heady with soma did Indra display some virtue—or at least strength. But in the beginning it was Indra himself who had been denied the soma. He gazed with hatred at the three heads of Viśvarūpa, the Omniform One, son of the Craftsman, pampered firstborn of the cosmos, who drank the soma with one of his small heads while reading the Veda with another. Indra wasn’t particularly worried about not knowing the Vedas. But why did he have to be denied a liquid that might be exquisite? For a long time he studied the priestly hauteur of the Omniform One. Then he suddenly sliced off his heads.

No sooner was the ill deed done than Indra felt the urge to go further. For the first time he crossed the threshold of Tvaṣṭṛ’s palace. Empty rooms, fine-wrought. Indra had never seen what form can become when imposed by a knowing hand. He was intimidated, overwhelmed. But this wasn’t what he was looking for. In the half dark of a room sliced across by blades of light gleaming from tall windows, he found a golden basin brimful of some whitish liquid. At last, the soma. Like a weary soldier at the end of a long march, Indra drank it greedily, making no concessions to ceremony. He drank and crashed to the ground. The high ceilings, all fine stone tracery, began to expand. Indra crept into the vegetable pleats of the stone, like an insect. He rocked from side to side, no longer able to distinguish between what he was thinking and what he was seeing. He wasn’t afraid of being caught now. Murderer and thief: how pointless! The porosity of the stone called to him in a way that was far more urgent. Slowly Indra discovered that many worlds were folded away in that empty room, worlds of which he knew nothing. His huge body lay abandoned on the floor, arms and legs outspread. From ears, nose, sphincter, and phallus a liquid dribbled down. It formed a puddle all around him. Only the mouth stayed tight shut and dry. Indra passed out. He lay motionless for hours, moonlight shining down on his powerful, defenseless body.

It would be misleading to think of the slaying of Vṛtra as of a duel between a big, clumsy dragon on the one hand and a blond hero, Indra, on the other, bursting with courage as he sought out a weak point where he might bury his sword. It was all much more complicated. To start with, Vṛtra was a brahman. True, he slithered across the ground like a shapeless lump, yet his voice rang clear and sharp, the voice of a priest, of one who knows. This was hardly surprising: Vṛtra kept the Vedas hidden in his belly, handing them over to Indra only shortly before being slain by him.

But the most delicate question was something else altogether: from time to time, from Vṛtra’s mouth, one could hear the whispering of Agni and Soma, for they too were hidden in his belly. It was with them that Indra would be obliged to negotiate long and hard. “What are you doing inside that brute?” he said to them one day. “You belong to another world, to my world, why are you being so stubborn?” “This brute was born from us, when Tvaṣṭṛ threw me in the fire, or at least what you left of me when you drank me up, greedy and impetuous as ever,” said Soma. “This brute is our child, even if he did devour us afterward. What will you give us if we come over to your side?” added Agni. “You’re used to betraying and running away,” said Indra, who had recognized Agni’s voice. “And you are travelers. My part is the part of sacrifice. The sacrifice is a journey. It’s true that if you stay in Vṛtra’s belly, you will be able to recite the Vedas, but you will feel oppressed, glutted with monotony. Whereas with me there will always be something that gets poured away, from sky to earth. Something that flows, that travels, that appears and disappears. Think about it.” That night, as Vṛtra slept openmouthed, Agni and Soma slithered out on his saliva, stealthy and swift, and went over to the side of the gods.

In the beginning all the gods were shut away in a transparent membrane. They peered through at an outside as yet undistinguishable, an outside which, to be exact, didn’t exist. They were brimming with power, but obliged to hold back. In the darkness they knocked against each other. Father Asura, who had stuffed them all in the cavity in his body, in the warmth of that which prefers not to exist, felt that this was the only appropriate way of doing things. Or rather, he didn’t know what doubt was. He thought of existence as something eccentric and deceitful. In any event, reprehensible.

From that indistinctness beyond the membrane they heard Indra’s whisper, calling to them. Unlike the others, Indra had refused to be born from the vagina. It was “an ugly passage,” he said. He managed to get himself born sideways, from his mother’s flank. And he murmured that one day he would do something that no one else had done. But who was Indra? A solitary calf. The gods followed him silently with their eyes as he wandered around the fullness. But would they be able to maintain that powerful inertia forever? The first one Indra called to was Agni. “Come here, guest,” he said. “Leave your dark house and strangers will welcome you.” Agni was the first to emerge. Then Varuṇa slithered out. Last of all came Soma. What was it that drew them? It was this changing of tribe, cautiously, while yet remaining tied to each other, like a band of renegades. It was this passing on to another life, while still having someone with whom to remember the previous life. Then there was the mystery of that new word—yajña, “sacrifice”—which Indra was constantly flaunting and whose meaning they hadn’t really understood as yet (why, for example, must it have five ways, three layers, and seven threads?), but which seemed set to alter every equilibrium. Then Indra had hinted that it was connected with immortality. Better to achieve immortality than already to have it, they thought with divine logic. Shut up in their father Asura, they were immortal, of course, but deep down they were afraid of suffocating in that fullness. Like thieves in the night, they slipped out of the membrane. Silence and desolation lay all around. Yet that was the moment when the balance swung and a new regime was established. They still hadn’t grown used to an ever more diffuse and penetrating brightness, when they saw the waters burst in—the waters, the cows, the syllables, the chants, like the chatter of a gaggle of girls—and in the midst of the waves’ billow they saw a white patch, a swan, that would suddenly beat its wings and thrust its beak into the water in answer to the voices all around. They exchanged glances, then Agni said: “That must be Indra.”

Soon after the flight of Agni and Soma, Indra struck. Crushed and creased up in his agony like an empty wineskin, Vṛtra looked at his killer and whispered: “Now you are what I was.” The translatio imperii was complete, and the shapeless, shoulderless creature chose to seal it with his own words. But what was to become of that gasping carcass that had until so recently contained the supreme powers? “Nothing is dissolved, everything passes on,” thought Indra. “Split me in two,” groaned Vṛtra. So Indra split him into two parts, which went on swelling and contracting, the way a lizard’s severed tail will go on flicking from side to side. Still dripping with soma, one part moved toward the sky: that was the moon. The other became the bellies of men. They have never ceased to expand and contract since.

Agni was the last of four brothers. Three died before him, were lost. They all suffered the anguish of being “yoked.” Fire is ever in mourning for those brothers.

In the beginning, Agni was more like a spy than anything else. Hidden away, he watched the ṛṣis’ brides about their baths: they shone like altars of gold, like white slivers of moon, like crests of flame. Agni thought: “I shouldn’t get excited and desire them. When I am in the hearth at home, I can gaze at them for as long as I want and lick their feet too.” In the evening, the women stretched out by the smoldering logs and bared their feet. Agni loitered with them alone, studied them, desired them. He knew the soles of their feet, the folds of their robes. He slowed his flame down to be able to watch them as long as possible. His desire intensified.

The gods had gathered around Agni. They seemed friendly enough, but they were surrounding him. “We’d like you to be our hotṛ,” one began. “I don’t feel I’m a priest, I’m not up to it. Three of my brothers have already died that way. I don’t want to be useful to anyone. I just want to burn. They ran like madmen between earth and sky. Then one by one, they disappeared. I am no better or worse than they. So why try again? I cannot bear to have a yoke around my neck. Even if it is studded with emeralds. I don’t want to be obliged to follow just one path,” said Agni—and he fled. He wanted to hide, but where? Varuṇa is present, even when two strangers are plotting together. There’s nowhere safe to hide in this world. So Agni decided to hide himself in himself. For fire, hiding in oneself means in the waters. That was where he had once appeared from. Agni looked for a pond, for rushes rustling in the wind. He slipped into a bamboo cane. Finally he sensed that there was nothing above him. All was silent, no sound of messengers. In the pond a sleepy frog felt the water burn his soft, white belly. He looked around, nervously. Who could be disturbing this stillness? Was Agni back? Hopping slowly along, the frog went to find the gods. “Looking for Agni, by any chance? Check the canes in my pond,” he said. Once again Agni was surrounded. But this time they grabbed him like a wretched runaway. Yet still the gods spoke sweetly to him, reassuring him: “We won’t do you any harm, we won’t hurt you.” Agni bowed his head: “I accept, but don’t forget my brothers, let a part of the offering go to them.” “Don’t torment yourself, Agni,” said the gods. “Your brothers will always be near you. They will be the three sticks that mark out the fireplace. Something will fall on them too …” “If that’s how things stand …,” said Agni, sadly.

The mind was confined in a compound, like the Cows, like the Dawns. Whatever happened, happened inside a fence, inside the walls of a palace, inside a cave sealed by a great stone. Outside foamed the immense ocean of the world, barely audible beyond a thick wall of rock. Inside, in the compound, was another liquid, a “pond,” which, however small, was nevertheless equivalent to the ocean without. The ocean was outside the mountain but inside the mountain too. By splitting the rock, Indra allowed the inside ocean, “the ocean of the heart,” hṛdyá samudrá, to communicate with the outside ocean, the palpable ocean of the world. It was a moment that opened up a new way of knowing. For the ṛṣis it was knowledge itself, the only knowledge they wished to cultivate. Not the mind shut away in its airy cage reconstructing a conventional image that corresponded point by point to the vast cage of the cosmos. But, quite the contrary: the waters of the mind flowing into those of the world and the waters of the world flowing into those of the mind to the point where they become indistinguishable one from the other. The ultimate difference between the knowledge passed on by the ṛṣis and every other knowledge consists in this: for the ṛṣis and all their descendants, knowledge begins when the Cows flee from the compound, when the Dawns awake, when the Waters flow through the cleft in the rock, when the doors of the mind are thrown open and it becomes impossible to say which waters are flowing in and which flowing out, what is substance and what is the substance of the mind. And everybody else? They live in ignorance of the compound, the rock, the Cows, the Dawns, the Waters. It’s hardly surprising if misunderstandings abound.

How often Indra was greeted as he who had opened the rock of Vala, who had freed the Cows, who had let the Dawns loose in the sky. But Indra knew it wasn’t true. And he knew that others knew too: the watchful eyes of Bṛhaspati and the Aṅgiras were ever on him. He couldn’t pretend with them. For it had been Indra, the hero, who had fallen into line behind them, the priests—and not vice versa. It was from them that he learned to transform his harmless babble into a whisper that worked, that changed things.

So Indra preferred to tell the story of how he had slain Vṛtra. Here too he had been helped—and helped a great deal. But the story could be presented as a duel between two champions. And when handed down by word of mouth, that was all that would be left: a monster and a hero, a handsome hero with a blond beard that dripped with soma. Yet nobody ever took Indra completely seriously. Alone, downcast, gazing at the stagnant water of a pond, he would say to himself: “You can make the whole world—and still it’s not enough. They’ll always look down on you with their arrogant, unblinking eyes.” They, the brahmans.

Indra wasn’t an intellectual god—and the ṛṣis often treated him with disdain for his hotheaded adulteries, his tawdry adventures. But at bottom Indra existed to accomplish a single deed: the splitting of the cosmic mountain. Without that enterprise there would have been no knowledge. Especially not the knowledge the ṛṣis cultivated. All this we owe to that vigorous, impure god on whose body the ṛṣis mockingly tattooed scores upon scores of vulvas. It wouldn’t be right to say that Indra gave an order to nature and made it possible for the world to exist. There was already an order—even with that mountain looming between earth and sky and keeping its treasures prisoner. What was missing was the flow within the order. That was what Indra made possible.

Indra is needed because without him there are things that can’t be done. But then he is left to one side, a cumbersome relic. A Western cousin of his, Apollo, loosed his arrow at Python, coiled up like Vṛtra on the mountain at Delphi. Indra too could claim to have slain the monster. But when Apollo had conquered Delphi, he made it the place of possession, which is composed of divination and syllogism. Indra wasn’t in a position to aim so high. With ṛta in the sense of “order,” he still had much to do, when he settled the world down, clipped the wings of horse and mountain, or scooped out the beds of the celestial rivers. In his role as cosmic engineer he was respected and even loved. But what did he know of ṛta in the sense of “truth”? In only one of the seventy-seven times it speaks of him does the Ṛg Veda grant Indra the epithet ṛt van, “endowed with truth.” The realm of the true word, the realm to which nature answers, was closed to Indra. Others had claimed it before him, severe and secretive figures who shunned him as a parvenu. Hounded by guilt and derision, ultimately ousted by a child god, Skanda, after having so often been mocked himself for being new and self-made, Indra ended up wandering around like a melancholy king beset by ungrateful subjects who look the other way when he passes by.

van, “endowed with truth.” The realm of the true word, the realm to which nature answers, was closed to Indra. Others had claimed it before him, severe and secretive figures who shunned him as a parvenu. Hounded by guilt and derision, ultimately ousted by a child god, Skanda, after having so often been mocked himself for being new and self-made, Indra ended up wandering around like a melancholy king beset by ungrateful subjects who look the other way when he passes by.

For a long time they walked through the shadows, following the tracks of the she-dog Saramā. Leading the way, face ever set in the same expression, Bṛhaspati cleared their path. Then came the Aṅgiras, all moving with the same rhythm, like a single person. Indra, with heavier step, brought up the rear. Having reached the horizon, they pressed on without a moment’s hesitation. They trod the back of the sky. Thus for days they marched while beneath them the deserts stretched out like vast carpets and the forests shrank to dark stains. From time to time they would be caught by gusts of opalescent Stardust. Beneath them, far away, the earth. Above, close by, the stars, like ships in the night. They looked neither behind nor below. Without turning, Bṛhaspati raised his hand. Indra looked up and saw an immense wall of smooth gray rock. “Why does it seem so earthly? We’ve left the earth behind,” thought Indra. Above them the rock seemed to stretch away forever. It had the nobility, the coldness, of something that does not wish to exist. It ignored them, as it had always ignored everything. “Here it is,” said Bṛhaspati. They stared in silence. A long time passed before the Aṅgiras began their murmuring. In the indistinct stream of sound, occasional syllables flared and faded. Bṛhaspati was rapt in thought. Then he joined in with his sharp, almost shrill voice. Indra was the most uncertain, then followed the others’ example, with clear tones. They fell silent again. There was a distant shuffling. “They’re in their stall,” said Bṛhaspati. “The secret names of the Cows number one and twenty. We must find them all,” he added. There was a faint light and an immense solitude. For a long time they stood motionless. Perhaps for years. There were no witnesses, unless hidden behind the glow of the Bear. All of a sudden, a few sharp, silvery syllables sheared off from the dull, monotone murmur. Chained together they pealed out. They became meters, recognizable as contours. They stood out in the air. From behind the rock a distant lowing answered, and swelled. From the darkness, the Cows. Slowly, like a fabric torn away thread by thread, a cleft began to open up in the rock. They gazed long on that thin line, etched in the grayness by some invisible hand. Ceaselessly they uttered the syllables. They composed names. A stream of light and dust, a clatter of hooves, a dazzling herd. The Cows emerged from the cave of Vala. The light was made of waters, which filled the sky. On the crest of the waves came the Dawns. Like songsters on a merry-go-round, clutching papier-mâché carriages, they rode the foaming billows, pink breasts leaning into an empty sky. Behind them, like a sovereign and a shepherd with his crook, who comes after his flock, appeared the Sun. Saramā barked. No one paid her any attention. Bṛhaspati, the Aṅgiras, and Indra looked on with glazed and happy eyes.