Shortly before the Bodhisattva entered into his last existence, the house of the noble Śuddhodana, chief of the Śākyas in Kapilavastu, suddenly appeared “free from weeds, free from dead tree trunks, free from thorns, free from gravel, free from sand, free from waste, well watered, well purified, free from eddying dust, free from darkness, free from dirt, free from gadflies, mosquitoes, moths, free from snakes, full of flowers, smooth as the palm of a hand.” It seemed everything was preparing to take on its definitive form. The countless and the shapeless were put to one side, like a crowd of extras waiting in the wings. A small number of elements, not further reducible, prepared to submit themselves to the gaze of the great decomposer of the existent world.

Māyā was lying on her left side. Numerous metal rings circled her ankles, wrists, and arms. An embroidered cloth was wrapped around her hips. A round breast rested on the back of one hand. It pushed out as though from a balcony. The other hand was bent back behind her head. A small, white elephant came down through a crack in the ceiling. It sank through the air toward Māyā’s uncovered right flank. Then it slipped in there, opening a passage for itself in the soft, smooth surface. When he was inside his mother’s body, the Bodhisattva settled down in contemplation. He looked through the transparent skin. He never moved until he was born. Meanwhile, Māyā dreamed of an immense white elephant, experiencing a pleasure she had never known before.

The Bodhisattva was born the way a king descends a flight of stairs. Contemplative and knowing in the heaven of the Tuṣitas, he descended mindful and knowing into Māyā’s body. During the months of pregnancy, when she was alone, his mother watched him in the crystal casing of her womb. And she always found him motionless, composed, attentive. When Māyā felt her hour approaching, she wanted to go home to her parents. She traveled on a chariot drawn by young girls. Halfway there she ordered the procession to stop in the woods at Lumbinī. She could feel the first pains of labor. She sought out the shadow of a tall śāla tree and gripped a branch. Eyes staring into the void, she remembered a white elephant she had dreamt of one night. Her maids hung an embroidered veil on the branches of the śāla, as a screen. The only sound was the humming of bees on a hedge thick with flowers. Māyā gave birth to the Bodhisattva standing up. The child was laid on an antelope skin, then a silk cushion, then the ground. They protected him with a white parasol. From then on, wherever he went, a white parasol always went with him. After the birth, Māyā, the baby, and their entourage went back to Kapilavastu. Seven days later, Māyā was dead.

Remembering his childhood and youth, the Buddha said: “I was delicate, monks, extremely delicate, too delicate. They laid out three lotus ponds for me in my father’s house: blue lotuses in one, red in another, white in the third. I wouldn’t use any sandalwood that did not come from Vārāṇasī, my clothes—my tunic, my robe, my cloak—were made of Vārānasī cloths. Night and day I was protected by a white parasol to keep me from the cold and heat and dust and weeds and dew. I had three palaces, one for the cold season, one for the hot season, one for the rainy season. During the rainy months, I would shut myself high up in the top of the palace and never come downstairs. The only people around me were minstrel girls. I didn’t even think of leaving the palace. And, while in other houses people offer a broth of rice husks to slaves and laborers, in my father’s house we gave the slaves and laborers bowls full of rice and meat.”

Eighty thousand girls could claim to have been born the same day as the Bodhisattva. They took turns in his three palaces, became his lovers and musicians, for thirteen years, as earlier they had taken turns as his playmates. His chosen wife was called Gopā. One thing we know about her is that she refused to wear a veil of any kind. Nobody could understand why. It was an allusion to the preceding age: when Kṛṣṇa’s gopīs heard his flute approaching, their plaits would come undone of their own accord and the veils supporting their breasts fell away. Yet something kept the memory of Kṛṣṇa at bay. For everything that happened to the Bodhisattva happened, as it were, at a remove, was the merest copy. He belonged to the many who are called on not to invent gestures but to repeat those of others. But he was also the only one who would be called upon to extinguish gesture itself. By the time the Bodhisattva appeared, all events of whatever kind seemed to have lost their epic profile. Their only value was as a pretext for thought. And it was there, perhaps, that something new was about to happen. There, ever since time began, something had been awaiting the arrival of the Buddha.

The Bodhisattva’s life was coated by a uniform film, like the thin walls his father, Śuddhodana, had had built around the palace park. Whatever happened, there was always something slightly artificial and suspect about it. Why did the Bodhisattva only meet creatures of his own age? Why, whenever he approached the boundaries of the park, did the path veer off into thick vegetation that hid any trace of the walls and turn back? Was this the world—or a piece of temporary scenery whose real purpose was to hide the world? One day the Buddha would sum up those years in a single sentence: “Once, before I left my father’s house, I could easily obtain the five qualities of sensory pleasure.” That was all he said. Characters, faces, adventures, emotions: all smoothed out in just one sentence—cold, technical, quite without resonance.

The Bodhisattva was twenty-nine before he saw an old man. Then he saw a sick man. Then he saw a dead man. Three separate occasions, one soon after the other, in three corners of the park. Another day, in the fourth corner of the park, he saw a renouncer begging. He hurried back to the palace. He was nearly there with his escort, when he realized that Kṛśā Gautamī, his playmate of old, was watching him from the roof. She shouted something, but the words were muddled when they reached him, a slight, mad vibration. Then, as he came nearer, he understood: “Happy the mother, happy the father, happy the wife who has such a husband.” Why was Kṛśā speaking like this? The Bodhisattva was fascinated, almost stunned—and only one word, “happy,” sank in to his mind. He had the impression that for the first time its meaning flashed alight for him, precise and distinct as any object. Then he took off a magnificent necklace and told a servant to take it to Kṛśā Gautamī as a gift.

Kṛśā’s hands trembled: she looked at the necklace, moved. “Finally,” she thought, “a message of love. Perhaps I won’t have to waste away just looking at his almost violet hair.” Her friend hadn’t been paying her any attention for quite some time. She wept for joy, not realizing that the necklace was a gift of farewell.

That night the Bodhisattva woke alone in his high bed. Moonlight bathed the summer palace pavilion. It lay on the bodies of the minstrels huddled on the floor, as though on a landscape of low hills. Carafes, cushions, shawls, sandalwood. Arms clasping lutes and drums like lovers. The Bodhisattva went on gazing into the half dark. Suddenly he saw reality ablaze.

As he had been returning to the palace, an excited messenger had come toward him to tell him that Gopā had given birth to a son. “Rāhula is born, a tie is born,” murmured the Bodhisattva. He hadn’t wanted to see the child. He had immediately withdrawn to the most remote part of the palace, a place open to the breeze. Now, in the silence of the night, he thought that before leaving he would like to see his son this once. He gently pushed the door of the room where Rāhula’s mother lay sleeping. A perfumed oil lamp spread a faint light. One of Gopā’s hands was covering the little Rāhula’s forehead. “If I move Gopā’s hand, she will wake up, and that will make it difficult for me to go.” Thus the Bodhisattva left the haunts of his childhood and youth in silence. His horse’s hooves didn’t touch the ground, because every time they came down a large and loyal Yakṣa slipped his back beneath.

Śuddhodana was not surprised by his son’s sudden departure. Behind every other, life offered but two possibilities: to be sovereign over the world—or to free oneself from it. Siddhārtha Gautama had already savored the first. There were numerous—and much admired—examples of those who, from the earliest times, had chosen the second. There were men, often powerful men, who one day disappeared. One said of them that “he has gone into the forest.” From that day on no one ever saw them again, except by chance perhaps. They were called saṃnyāsins, “renouncers.” They renounced what had made up their lives before that day. And having spent their lives celebrating the rites with impeccable propriety, they now practiced them no more, or at least not visibly. Having parceled out their days in obligations and precepts, they now had no habits at all. Having provided the wherewithal for huge families, they now kept no provisions. Having sought to attain herds, children, and long life, they now made no plans. For years they had built themselves up in an architecture of actions cemented one upon another. Now they sought immobility, because that way they could at least escape from every visible gesture. But the more subtle masters soon discovered that action, karman, went on accumulating, even in silence and immobility. They would have to go right down to the secret chamber of the mind and flush it out. But how could they get in there? And how could one act to extinguish whatever it is that acts? “Many have tried …,” murmured Śuddhodana, his thoughts turning nostalgically to his son. “Many have tried …,” said Siddhārtha, already wandering through the forest. “This will be my achievement,” he added, in the silence.

There were sixty-two schools of thought when the Bodhisattva left his father’s house. And six eminent masters. Pūraṇa Kāśyapa claimed that actions do not give rise to retribution. Maskarin Gośālīputra claimed that the course of existence is already established and that effort of any kind is pointless. Ajita Keśakambalin claimed that a human being is made up of four elements, which come apart at death. Kakuda Kātyāyana claimed that the human being is made up of seven permanent elements and that, when someone is murdered, there is no murder or murderer or murder victim. Saṃjayin Vairatīputra claimed that there is no definitive answer to any metaphysical inquiry—and thus they called him “the eel.” Jina Mahāvīra claimed that in each life one must do severe penance to expiate the crimes committed in previous lives.

The Bodhisattva sought out, followed, then left two masters. He realized they would turn him into a charred log, while one ought to be a leafy tree. He wandered around alone for a long time. He thought: “The life of those who live without a home is rubbed smooth as a seashell.” He found his locus amoenus in Uruvilvā. “Then I thought: ‘Truly this is a delightful spot, a fine forest; clear and pleasant runs the river, with pretty places to bathe; there are villages round about where one can go; this is a good place for a noble man in search of salvation.’ ” Two thousand, four hundred years later, when Hermann Oldenberg visited, Uruvilvā still looked “delightful,” and, even if it was less densely wooded, there was still a scattering of majestic trees. It was winter, the river almost dry in its wide, sandy bed. Another scholar, Karl Eugen Neumann, had compared the place with the lower regions of the Main. Oldenberg did not agree.

How did Buddha behave in Uruvilvā? He was like a gazelle in the forest, an antelope, a fawn. “When I saw a cowherd or a goatherd or someone going to cut wood or to gather grass or to work in the forest, I would run from thicket to thicket, bush to bush, valley to valley, peak to peak. Why so? So that they wouldn’t see me and so that I wouldn’t see them.”

The turning point in the Buddha’s life did not come when he left his father’s house. From Annapūrṇā to Cape Comorin, from the thickest forests to the promontory’s ocean plunge, the country was crawling with renouncers. To don the ocher robe and set off along the road, begging bowl in hand, was considered an entirely normal thing to do, scarcely less so than living as the father of a family celebrating the rites around the domestic hearth. It was the way of the forest. And “forest” had never referred merely to the place that surrounds—how far?—the place where men live, but to the secret doctrine. To understand the world of men, and indeed every other world, one’s point of observation must be out there in that harsh, dense realm where only animal voices were to be heard. It was the metaphysical place par excellence. He who thinks out in the forest is left entirely to himself; there he touches bottom, the baseline otherwise hidden beneath human chatter, there he goes back to being like a wild animal, which is the closest approximation to pure thought.

No, the turning point in the Buddha’s life came six years later. It was then that Śuddhodana’s son, a Śākya from Kapilavastu, provincial noble, renouncer, disciple of various masters, began to consider himself with an uneasy smile. He had felt his breathing come like the bellows of a furnace. He remembered the time well. Then the ferocious headaches that followed, the hot flushes that overwhelmed him. Then there were long periods of fasting, his scalp turned wrinkly as a wind-dried pumpkin. Two masters had attracted and then disappointed him. None of this had helped him to see what is as it is. Why not? He didn’t know, but an image came to his mind. Two sticks of green wood. He tried to rub them together to start a fire. Nothing happened. Then he took two other sticks: they weren’t damp but were still full of sap inside. He tried to start a fire. Nothing happened. Then, excited, he thought: “It takes two dry twigs …” Those childish words brought him an odd happiness, somehow allusive, though to what he couldn’t say. He wasn’t thinking of his life as a wandering monk now. But another, more distant memory came to him.

His father, Śuddhodana, was working in the fields. Perhaps he was plowing. Under the jambū, a rose-apple tree, left lying there like some bundle or other, his son watches. He’s a little boy, scarcely more than a baby. He looks around and senses how pleasant the air is, and the hills, the shade, the grass, the branches. There is nothing else on his mind. His father is absorbed in his work and doesn’t turn to look at him. Nobody is looking at him. The world pays no attention. The boy’s eyes slowly scan the whole scene. There is no resistance, there is no tension, there is no desire. Everything is completed, self-sufficient. There is nothing to add, nothing to subtract. Cautiously, the mind penetrates itself, then, almost playing, formulates these words: “Perhaps this is the way that leads to awakening.” And a question forms: “Are you afraid of this happiness?” He thought: “I’m not afraid of this happiness.” Then the boy became a man. He was alone and disheartened. He thought: “What lies hidden in this memory?” He realized he was whispering two words: “Dry twigs.”

Later he resumed his thinking: “Those doctrines they taught me, those harsh exercises, there’s still too much desire in them. That’s the sap that drips. These motionless, rigid wise men would like to become pieces of wood. But it is wet wood.” Supple, loose-jointed, that boy under the tree had wanted nothing. But dry twigs were rubbing together in his mind. He went on thinking: “That obstinate striving does not lead to awakening. It’s a curtain that cloaks the mind. When the curtain is moved aside and happiness flashes out, it frightens us like the sudden movement of a wild animal. And why does that happiness frighten us? Because it isn’t born of desire.” Inside himself he added: “Then it is unlikely that that happiness will flash out if one’s body is exhausted.”

Then Śuddhodana’s son, whom few would now have recognized in this solitary, emaciated monk, got to his feet and set off on his way again. When he went through a village, he asked for the same food everybody else ate, as if he were a normal traveler. Thus the Tathāgata—He-who-came-thus—came down to us, the Buddha.

The Buddha rarely uses images—and when he does so they are very simple, to be cherished like talismans. They said what analytic dissection was unable to say. Often they alluded and referred back to Vedic images, to those times when everything that was said was imagery. But the allusion was not meant to be noticed, as though the images were now being discovered for the first time. The “dry wood” of correct meditation is the araṇi, the twig that serves to start a fire, that conceals Agni and is the first of all sexual creatures. That friction of one wood against another had once lain at the origin of every kindling, cosmic and erotic. Now, as used by the Buddha, what stood out most in the image was this dryness, this draining away of every drop of sap, which made the wood precious. Even the images were dried out.

Tathā, “thus,” was the Buddha’s favorite word. Not just because he liked to go by the name of Tathāgata, He-who-came-thus. But because the Buddha taught others to see the tathatā, the “thusness” of all that is.

When the Buddha taught people the Middle Way, the only way that is free from error, he also said: “One should speak quite slowly, not hurriedly, one should not affect the dialect of the countryside, one should not deviate from recognized parlance.” Only what is neutral, free from glaring features, only what blends in with all that is common, only what least departs from “thusness” can save us.

It was May. There was a full moon. That night the Bodhisattva had five dreams. Upon waking, he thought: “Today I will achieve the bodhi, the awakening. Everything will be exactly as before, as now when I woke up. But I will consider all that happens as now my mind is considering those five dreams.”

A girl, Sujātā, stepped forward. The Bodhisattva had met her before in Uruvilvā. Shyly, she held a golden bowl, brimful. Without a word, she offered it to the Bodhisattva. The Bodhisattva took the bowl to the riverbank. He sat and ate. Then he tossed the bowl in the river. Meanwhile he was thinking: “If the bowl floats upstream against the current, I will become a Buddha today; if that doesn’t happen, let the bowl follow the current.” No one knows how much doubt he felt, if any at all. The bowl drifted to the center of the stream. Then all at once it darted like a horse across the surface of the water. It was racing upstream on the crests of the waves. Further upriver there was a whirlpool that sucked everything down into itself. A Snake lived there, a Nāga. The bowl sparkled a moment on the eddies, then disappeared. On the bottom it bumped against three other bowls, covered in waterweed. They had been there for thousands of years and had once belonged to three other Buddhas. The new arrival settled on the muddy bed, a little further down from the others.

If we translate bodhi as “illumination,” as most people do, the word is, like it or not, metaphorical and points toward the world, the light that pours down upon the world. If we translate bodhi as “awakening,” the word corresponds exactly to its early usage in Sanskrit, from the root budh-, “to wake,” and points exclusively to the mind, to what happens in the mind and has no counterpart in the manifest. It is only by enhancing this characteristic, which the mind shares with nothing else, that one can achieve that detachment from the existent world, that separation from what is given, that irreversible caesura: the bodhi that transforms Prince Gautama into the Buddha, into the Awakened One.

During the second quarter of the night of awakening, the Buddha remembered his previous lives. First one, then two, then five. Soon he stopped counting. Names appeared—and he would say: “That was me.” He saw places—and said: “That was me.” He saw passions flare and fade. He saw people dying—and said: “That was me.” A throng of faces, clothes, towns, animals, merchandise, roads. He went on watching. He had stopped repeating “That was me.” And suddenly he realized he was watching the lives of others. He didn’t notice any fundamental difference. He pressed on, amazed, but amazement was a constant in these migrations through time. True, he could no longer say: “That was me.” But was that really so important? He could still recognize the joy—and above all the suffering. The scenes he had lived through and those he had not lay side by side, each attracting the other, like leaves in a pond. The light they emanated fused into one. As soon as the eye retreated, they became a thread of beads, each with a slightly different color, and here and there a small chip.

For seven days after the awakening the Buddha remained seated. Then he got up and gazed long at the fig tree that had protected him. He looked over every inch of it with an elephant’s eye. After fourteen days the Buddha got up again and began to walk. He wasn’t going anywhere in particular. Not far away, Māra collapsed, defeated. He wrote on the ground with his stick. Tantrī and Aratī, his daughters, came to read: “Gautama has escaped from my clutches.” Devoted to their father and used to seeing him triumph, the two girls eagerly asked: “But who is this man? Do you want us to bring him to you in chains? He will be your slave.” Māra shook his head and nodded to the signs he had traced in the dust. Then he said: “He has routed my armies with a cough. He has put my roaring troops to flight by skimming the palm of his hand over the ground.” Then Tantrī and Aratī decided to seek out this stranger. They found him walking slowly along. They followed him, furtively, to get his measure. He was a man—they told themselves—and they knew how to deal with men.

All at once they stepped out from a bush and came gracefully, obsequiously, to meet him. “We would like to adore your feet, O happy creature,” they whispered. The Buddha kept on walking. Then the two girls started following him, walking right beside him so that they were almost brushing against him. “Many are the desires of men. Many are the desires of men …,” they repeated, concentrating on their words. The Buddha showed no sign of having heard them. The two girls stopped to consult. “Let’s transform ourselves. Let’s each become a hundred fifteen- or sixteen-year-old girls,” said Tantrī. Gravely, Aratī agreed. Now the Buddha was walking in the midst of a procession of girls, all making one of the twenty-three gestures of female seduction. They all kept saying: “We would like to adore your feet, O happy creature.” The forest was full of tripping chatter. The Buddha kept right on walking. Soon the girls disappeared.

The Buddha was sitting under a tree. Tantrī and Aratī reappeared. This time Aratī spoke in a cold, sober voice: “Are you in the forest because you are overwhelmed by some grief? Do you plan to pass your life in thought? Have you insulted the inhabitants of your country and are unwilling to make peace with them? What other reason is there for being so alone?” The Buddha answered as if picking up an old conversation: “I have torn up the roots of grief. I have no thirst for life.” Then Aratī remembered that adulation can prove the supreme weapon. She started again, wheedling this time: “If that is so, many will follow you. Already I see multitudes behind you.” The Buddha interrupted her: “You are scratching a mountain with your nails. You are biting on iron. Why are you following me, if not out of envy?” The two girls stood up, pale and beautiful. They went back to their father. Aratī said: “Father, today I was defeated.” Māra looked up: “He brushed you off like a ball of cotton.” Then he got up and, still gloomy, left his daughters alone.

The Bodhisattva’s first five companions left him because they disapproved of his decision to eat normal food. They were convinced that this amounted to giving way to the world. One day they were sitting beside the road when they saw him reappear, some time after his awakening. They were already thinking of something sarcastic to say when his expression froze them. Throats tight, they were about to utter his name and nothing more: Gautama. The Buddha sketched the barest of gestures with his hand to stop them, and said: “I am the Tathāgata, He-who-came-thus. That is the name you must call me by.”

Śāriputra and Maudgalyāyana were young, rich, handsome, and noble. Together they experienced the feeling that the world is vanity. Together they set out to seek the truth of the matter. They agreed that the first to find it would tell the other. Thus one day, in the narrow streets of Rājagṛha, Śāriputra met a monk who immediately made an impression on him. He had an enchanting way of moving, of going forward and backward with his beggar’s bowl. A way of holding his arms, of always looking at a point some distance away on the ground, and always the same distance. All his gestures were as if supported by threads. Śāriputra followed him for a long time before speaking to him, and when he did so it was with the politeness of someone who has been tempered by a strict education. “How long is it since Your Lordship left his family?” he said. “Not long,” answered the monk. It was Aśvajit, the slowest to understand of the Buddha’s first five companions. With due respect for good manners, which abhor questions that are too direct, but at the same time urged on by an impulse that demanded he find out, Śāriputra continued to converse with the monk. He wanted to know what doctrine could lead to such gracious behavior. For it must be a perfect doctrine.

Aśvajit was cagey. He was well aware of his own inadequacy. He had never been able to reconstruct the Buddha’s doctrine in all its various steps. He remembered his four companions, who had been illuminated before him. He thought how he always got there late, and was always plagued by a sort of blur, which, however, he now accepted without fuss. Looking at the ground he whispered: “I shall never be able to expound the doctrine in all its vastness. All I can do is hint at its spirit.” For a moment Śāriputra dropped his wary, delicate manners. With great excitement in his eyes, he simply said: “That is what I want.” So then Aśvajit said: “The Master has shown how phenomena spring from one cause. He has said what the cause is and what the cessation of the cause.” At that very instant, immaculate, free from any speck of dust, the eye of the Law opened in Śāriputra.

Immediately, the monk and Śāriputra set off on their separate and opposite ways. Śāriputra was desperately eager to find Maudgalyāyana. He was proud to be in a position to keep their pact. He searched far and wide for a long time, but without success. He stared at all the travelers as if in a daze. But it was Maudgalyāyana who saw him one day from a long way off along a flat road. He immediately sensed a change in his friend’s face. His skin was as if brightened by serenity. As soon as he was within earshot, Maudgalyāyana said: “You’ve found it.” “I’ve found it,” said Śāriputra. “Now I’ll tell you.” Śāriputra then recounted his meeting with Aśvajit in every detail. He stopped a moment before repeating the monk’s words on doctrine. As had happened with Śāriputra, the eye of the Law opened in Maudgalyāyana. Now they walked along together, in silence. When the Buddha saw them approaching, and while they were still far away, he told the monks around him: “You see those two who are coming toward us? They will be my two best disciples.” And he welcomed them. People who had known Śāriputra and Maudgalyāyana in the past said: “They have set out on the path of that monk who steals children. A path full of widows. A path that destroys families.” The Buddha ordered the monks to answer only that it was the dharma that had taken away Śāriputra and Maudgalyāyana. Say no more. The murmuring would end after seven days.

Śāriputra and Maudgalyāyana were illuminated by two sentences. “Phenomena spring from one cause” is the first. There are those who might pass over this sentence as obvious. But it is a continent. Śāriputra immediately saw something new in those words. The world is a throw of the dice. And the worlds that follow are successive throws of the dice. They are phases of the līlā, the cosmic game. From infancy on, Śāriputra had been picking up this doctrine here and there, the way one gets to know the secrets of sex. But how can one recognize one cause, one origin, in a sovereign game that unfolds in the totality of things? Now someone was teaching: “Phenomena spring from one cause.” And then immediately afterward opening vistas on a further continent: “He has said what the cause is.” So it was possible, then, to have a vision of the precise point from which dependence arose, the way one can see, on the ground, the place where a spring of water rises. But perhaps the most momentous words for Śāriputra were those that followed: “He has said what is the cessation of the cause.” Cessation, extinction, nirvāṇa: the most popular, the most abused, and the most mysterious word the Buddha used. Śāriputra was still thinking how wonderful it was to be able to say what the cause is, when he heard that one could also announce the cessation of the cause. But had anything ever really ceased in this world, this perennial, endlessly repeated buzz? Such a doctrine was truly unheard of.

The Buddha’s life was ever tinged by colors of sunset and uncertainty. He wanted nothing better than to appear, announce the doctrine, and disappear. For him, everything sprang from the casual occasion, from what he encountered along the road. As for the doctrine, he decided to announce it only on the insistence of an unknown brahman with whom he had fallen into conversation one day—and who turned out to be Brahmā himself. The Buddha let events take him to the point where the word dropped from the branch. Thus even what was soundest seemed precarious, chancy. The epoch demanded it. Things had changed from the days of the preceding Buddhas, when life was long and men accumulated merits. The Law’s sun still shone, but the light it spread was weak now. As the venerable Mahākāśyapa said: reality was sick.

It took an immense effort for the world to achieve the ingenuousness, the improvidence of Locke, who spoke of the human mind as a tabula rasa. But then the dizzying gadgetry of the modern needed a perfectly flat surface to stand on. And that was the tabula rasa. In India, at the time of the Buddha’s birth, people’s assumptions could not have been more different. Every being was born as a tally of debts—a quadruple debt, according to Vedic doctrine: to the gods, to the ṛṣis, to his ancestors, to other men. But—and this doctrine became increasingly obsessive as time went by—every being was also born weighed down by actions already performed and attracted to others yet to be performed. We are born old, of an age that dates back to the beginning of time. Every life is a segment in which certain actions fade and others blossom. More than anyone else, the Buddha appreciated the mass of pain stored up in time by the accumulation of one act after another. Perfection is achieved when someone is about to put an end to the long series of actions. Then that person is surrounded by a sudden lightness, an emptiness.

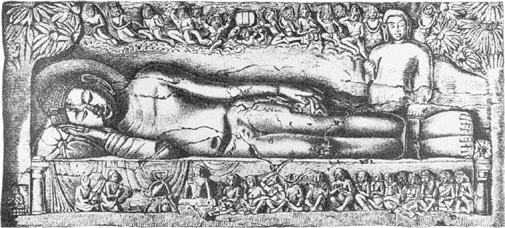

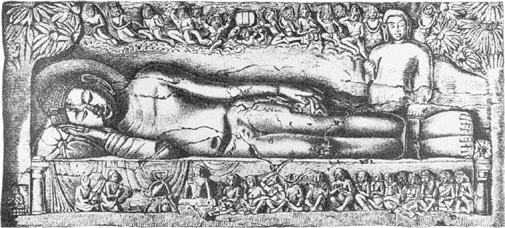

When the Buddha was born, he was close to that perfection. He just had to finish “doing what had to be done,” as one formula common among his disciples put it. Hence his whole life was a gesture of farewell. Hence it was overlaid with a patina of melancholy and absence. The loves of his youth—his father, his mother, his wife—these figures are barely sketched in. They have no features. They perform their functions and disappear. Perhaps this partly explains why the oldest depictions of the Buddha show him as an empty space in the middle of a scene, or at most represented by one of his attributes. As for the doctrine: it was a wheel between two antelopes.

From the first discourse in Vārāṇasī on, the Buddha’s words are analytic and repetitive. Everything seems to dissolve, except numbers. There are four noble truths, the path is eightfold, the objects of grasping are five. Whatever the subject under discussion, the Buddha takes it apart and reduces it to the elements, whose number he later established as seventy-five. A single word, dharma, is now used to designate both the “Law” and the “elements.” It is as if a discriminating eye had penetrated every nook and cranny, leaving nothing out, dividing everything up. And the procedure begins over and over, the same formulations endlessly repeated. All the more impressive, then, is the one omission: sacrifice—the word that in the past had been repeated more than any other, the word that had always been there at the beginning and end of every discussion, indeed had sometimes seemed to be the only object of discussion and the only theater of action.

Omission and substitution were the weapons the Buddha used to oppose those who came before him. He did not say a word against sacrifice (nor for that matter against the castes that derived from it). But if we consider the space the word “sacrifice” takes up in his teachings, we find it is minimal. Before him, it was immense. It is as if the prolixity of the Buddhist texts sought to make that omission the more momentous, to occupy all available space in order to deny that unspoken word any place of refuge, however small.

The Buddha made himself understood first and foremost through contrast. His strongest form of denial is not to mention something. He did not deign to name what others evoked and reiterated with every new day in an intrusive, all-pervasive murmuring. For the Buddha, not mentioning sacrifice was like ignoring the air he breathed, the ground he trod. The Buddha never quoted, in a land where every leaf that trembled was a quotation.

There was an obsessive attention to action. It went back to the very first actions—which were not even human, but divine. Yajñéna yajñám ayajanta dev s, “with the sacrifice the gods sacrificed to sacrifice”: so said the texts—then, to make it clear that nothing had happened before that, they added: “Such were the first institutions.” The gods had appeared, surrounded on all sides by sacrifice. Sacrifice was the tool, the object, the recipient of action. And any action accomplished was sacrifice. Would there ever be anything that was not sacrifice? Hence it came as the result of immense effort when people began to speak of karman: a neutral, generic word to indicate all actions. At first it was a secret. Then, with the Buddha, it became a ceaselessly declared and repeated secret, while sacrifice was now implicit, silently understood as action par excellence. But the most daring and devastating rebellions come when someone decides to ignore something implicit.

s, “with the sacrifice the gods sacrificed to sacrifice”: so said the texts—then, to make it clear that nothing had happened before that, they added: “Such were the first institutions.” The gods had appeared, surrounded on all sides by sacrifice. Sacrifice was the tool, the object, the recipient of action. And any action accomplished was sacrifice. Would there ever be anything that was not sacrifice? Hence it came as the result of immense effort when people began to speak of karman: a neutral, generic word to indicate all actions. At first it was a secret. Then, with the Buddha, it became a ceaselessly declared and repeated secret, while sacrifice was now implicit, silently understood as action par excellence. But the most daring and devastating rebellions come when someone decides to ignore something implicit.

The Buddha undid the knot that tied the victim to the sacrificial pole. But at the very moment he was undoing it, he explained that everything is a knot. From their vantage point in the heavens, the spies of Varuṇa, god of knots, were watching.

One of the many things the Buddha did not speak of was the cosmos. How the heavenly mechanics came into being, how it worked. Of what substances life was made and how composed. None of this seemed to interest him. With the exception of one invisible element: time. Of everything he said that it rose up and died away. That must suffice. He also said how something rose up and through what transitions it came to die away. But he was always referring to things of the mind. Outside the mind, he didn’t mention so much as a blade of grass. He rarely used similes, and when he did they were always the same, and almost always had to with poor materials. Sometimes he mentioned the lotus plant. Animals he mentioned were the elephant and the antelope. Yet the Buddha was fond of certain natural locations. What he loved best were the parks near towns. They were quiet, suitable for gathering one’s thoughts. And it was easy to leave them and find roads where one could beg. Around those parks and their silence, like a frame on every side, you could still sense the city’s roar and babble. The Buddha’s wanderings were punctuated by the rests he took in these parks. Some were donated to the communities of monks. Often they settled down there, stayed for some centuries. When the imperious believers of another faith sought to subdue India, such places proved easy to find and destroy. Behind them they left heaps of stone, smothered in vegetation.

What would one day be called “the modern” was, at least as far as its sharpest and most hidden point is concerned, a legacy of the Buddha. Seeing things as so many aggregates and dismantling them. Then dismantling the elements split off from the aggregates, insofar as they too are aggregates. And so on and on in dizzying succession. An arid, ferocious scholasticism. A taste for repetition, as agent provocateur of inanity. Vocation for monotony. Total lack of respect for any prohibition, any authority. Emptying of every substance from within. Only husks left intact. The quiet conviction that all play occurs where phantoms ceaselessly substitute one for another. Allowing the natural algebra of the mind to operate out in the open. Seeing the world as a landscape of interlocking cogs. Observing it from a certain and constant distance. But what distance exactly? No question could be more contentious. Adding this last doubt, then, to a trail of other gnawing uncertainties.

One becomes what one knows: that was the premise of the ṛṣis. “Men become like unto that by which they are intoxicated.” That was the premise of the Buddha. Why seek to know the world, if knowing it means being possessed by it? The thinking of the ṛṣis embraced the implicit risk that the-thing-one-becomes-like-through-thinking-it will take us over entirely, obscuring any further investigation, dominating the mind the way a Gandharva or an Apsaras will toy and sport with the person who hosts them, and whom they possess. This doesn’t just happen sometimes, but always and inevitably if one no longer accepts the immensity and continuity of the ātman, if consciousness is seen as the result of mere aggregation. The Buddha’s gesture was meant to counter a secret enemy: possession. That mental life is continually invaded—by what? powers? call them what you will, in any event elements that agitate—was revealed to the Buddha as the ultimate slavery, that bondage to which all others lead back. Mental life: objects looming before us, without respite, taking over, obsessing us. The gesture of grasping, of reaching out, like the monkey’s lean paw. This is the most precise image of mental life: restlessness, the pathetic tension of the monkey among the branches of a big tree. He who reaches out to grasp is himself grasped, possessed by the mental object that looms up and imposes itself. There is only one circumstance in which this doesn’t happen: if one is able to recognize a common trait in all those objects: emptiness.

The Buddha turned the Upaniṣad formula tat tvam asi on its head. “You are that” tells us that, whatever appears to us, “you are that”: that thing is within you, is in the Self, which—immensely larger than any thing, spreading out from the barley grain hidden in the heart—includes within itself, little by little, every shape that appears. Nothing is alien to it. And being everything that appears gives us the basis for understanding everything that appears. “As if the universe was captive, lost in the midst of my consciousness,” as one Vedantic master, though unaware of being such, would one day remark.

There are shapes that can equally well be seen as convex or concave. An instantaneous adjustment of the eye will do the trick. The Buddha’s doctrine is concave. Pūrṇa, “full”; sūnya, “empty.” Fullness drawn from fullness: this is the Vedic doctrine. Emptiness drawn from emptiness: this is the Buddha’s doctrine. The transition from the Upaniṣads to the Buddha is one from fullness to emptiness. But the shape is the same. What opposition cannot do, affinity may. They are not hostile shapes, unless perhaps in the way the case is hostile to the razor it conceals.

For the ṛṣis the pivotal word was tapas, “heat.” For the Buddha it was nirvāṇa, “extinction.” Perfect correspondence, poles apart. Inversion. In the land they lived in, extinction was thought of as fire going home, withdrawing into its dark dwelling. Premise common to both the ṛṣis and the Buddha: what happens in fire, with fire, is crucial.

The boldest character of all, he who took the irreversible step, origin of every deviation, first subversive, was the renouncer. A solitary figure silently sets out from the village and disappears into the forest. From the Buddha to the individual, in the purest Western sense, all are descendants of the renouncer. It was the first gesture of detachment, of cutting loose, from society camouflaged in nature—and from nature camouflaged in the cosmos. It was the first recognition of a world beyond yet still within this world, and of the possibility of setting up home there, of observing the horizon from there. An order that might be the shadow and counterpart of the other order. Or of which the other order might be itself the shadow and counterpart. One served mostly for living. The world beyond mostly for thinking, without restraint. The world beyond was the forest, thought cut loose from any doctrinal obedience, form released from any ceremonial obligation.

Wrapped in robes of ocher and white, Jainist and Buddhist monks migrated throughout the world. Others, faithful to the Devas, recognized them as heirs of the Asuras. It was a question of their being not enemies now but heretics. People heard them teach severe doctrines that ridiculed ceremonial practices and shook the world as though it were no more than a rag doll. But time’s slow grind changed this too. There came a point where one could no longer say whether these doctrines really were incompatible with those of the ancient gods—and many figures reappeared in the Buddha’s halo, crouching in the light. Brooding, intertwined, dancing. The divine wheel reemerged, as if fished up from deep waters.

If there was something that frightened them right from the start, it was the mind’s dispersion. Passing rapidly and without respite from one point to another, the mind sought to duplicate the world, superimposing its own spider’s web over the web of the visible. In the end this diminished its power rather than enhancing it. The world remained intact, sovereign—outside the mind and inside it too. To overcome the world (and this demands a first step: seeing it), the mind must gather itself up, the way the hand must gather a clump of grass before the sickle can cut it. The sickle is “wisdom,” prajñā. The hand that gathers is attention.

The thirty-three gods, they say, are immortal—or, more precisely, they live an extraordinarily long time, many millions of years—or, even more precisely, they were originally wretched and vulnerable like normal men, then one day they won immortality through sacrifice, but not a full immortality, since at some time, however remote, it must end. In any event, their long lives did not grant them metaphysical supremacy, which belongs to knowledge alone, and above all to being conscious of knowledge. Which is why the Buddha—at the end of time—and the ṛṣis—at the beginning of time—treated the thirty-three gods in such an offhand, impatient, and condescending fashion, as immature and muddled beings, not to be taken entirely seriously. The ṛṣis and the Buddha Śākyamuni knew that up in the heaven of the Tuṣitas the gods were abandoning themselves to supreme pleasures. But in the end, what difference can it make whether a pleasure lasts millions of years or just an instant? The only thing that makes a difference is the discrimination that creeps into pleasure’s veins.

The most radical attack ever leveled at analogy was conducted by the Buddha. It wasn’t that he denied its existence. On the contrary, he accepted it as something obvious that reaches out to everything there is. The world, of course, was a fabric, a thin, metallic mesh. But it wasn’t the individual, ever-different shapes from one link to the next that mattered. What mattered was that it was a net, something that covers, that tightens, that can suffocate. This was the true, dominant, omnipresent analogy. An expert eye could sense it in all the variegated diversity of the apparent world. And one day it would sense only that, discarding the individual shapes as irrelevant. But if that was the case, then every stitch could be substituted by any other. And at this point, where everything was analogy, mightn’t one more exactly say that everything was substitution? The unending net of the bandhus, of the “connections,” became a single lace, whose various parts had no distinctive features save that of reinforcing the general constriction. It was called pratītyasamutpāda, the interlinking of everything that arises.

The Buddha breaks the analogical pact. He ignores correspondences. He doesn’t deny their existence, but he belittles them. Why concern oneself over echoes of like and like when all elements are anyway linked together in the same chain, in the way they manifest themselves, and for the mere fact that they do manifest themselves?

The tragic is the unique and irreversible act. To elude the tragic, the Buddha dilutes every action in a series of actions, every life in a series of lives, every death in a series of deaths. Suddenly everything loses its consistency. Whatever is multiplied is also extenuated. Simultaneous with this gesture came the epistemological denial of the existence of the Self, now reduced to a series of elements that can be added together and unified in conventional fashion.

Convention, the supreme power of the modern, proceeds along a path cleared before it by a dry, cautious, analytic monk, who drained away the energy of the divine figures without even taking the trouble to remove them.

“The animate universe, like sand in the fist,” said the Buddha. A multiplicity of tiny elements, all entirely alien to one another. Trapped in the same grip. But this is their one affinity. In every other respect, each grain is on its own, unconnected with the others, even though the substance is always the same.

The Buddha was in no hurry to go back to Kapilavastu. But one day he did reappear in the place where he had spent his infancy and youth. His son, Rāhula, was there, whom he remembered as no more than a shadow in his mother’s bed, the night he had left her. When she got news of the Buddha’s return, Rāhula’s mother said to her son: “Now go to your father. Go and ask him for your inheritance.”

While the Buddha was wandering around northeast India, stopping from time to time to expound the doctrine to his followers, history went on just the same. So the day came when the Śākyas were massacred. That morning the Buddha told his monks that he had a bad headache, as if a stone were pressing down on his head, a stone that was a mountain. Meanwhile, one by one, his relatives were being exterminated, and with them the entire tribe of the Śākyas. Virūḍhaka, king of the Kosalas, had launched a surprise attack. Following an ancient tradition, the Śākyas were excellent archers. But because they had heard the words of the Buddha, they were no longer willing to kill. Hence, though their arrows were able to slow down the massacre, they could not stop it. Virūḍhaka had brooded long over his vendetta, ever since those wretched provincials at Kapilavastu, who spoke as if they were guardians of the dharma when in the end they were just his subjects like anybody else, had called him “son of a slave.” He wanted that arrogant, unarmed tribe to die in agony. He had a large number of pits dug and ordered that the men and women be piled in them, packed tight. Then he had them trampled on by elephants. There were only a few, desperate survivors. They reached the Buddha in the forest and told him what had happened. When they left, they asked if they could take some relics with them. The Buddha gave them a few hairs and nail parings. After that, he never saw them again. It is said that they founded a kingdom in Vakuḍa, a place no one has ever seen.

The Buddha was alone now. He had no relatives, nor any home to go back to. Kapilavastu had been razed to the ground—and likewise his much loved Park of the Banyans. Of his family, his cousin and constant shadow, Ānanda, was the only survivor. Together they made no comment. Not even when a few days later they heard that Virūḍhaka and his troops had been drowned in a torrent of floodwater that had swept down the stony bed of the Aciravatī River. Gloating over their loot, the Kosalas had camped there for the night.

Like Kṛṣṇa, the Buddha can only appear close to the “dissolution,” the pralaya. Behind these two there is always a massacre. Before them, a stretch of water swollen with wreckage. At least Kṛṣṇa had fought, and intrigued, though he never bore arms. The massacre came about just the same. Not so the Buddha. He did not intervene. And once again the massacre took place. Had they stood in its way somehow? Had they instigated it? Had they let it happen? Perhaps the massacre was just a premonitory sign of the real and inevitable event: the rushing floodwater that would dissolve all, wipe away the profile of a world and return it to what it had originally been: a residue. And among those residues, among the uprooted trees, the sodden timbers and washed-out rags, barely distinguishable from the endless watery surface, a coiled snake, soft as a cushion, would one day emerge. An adolescent body lay on that bed, carmine lips opening to the sky.

Why was the residue granted this privilege? Why, rather than representing the insignificant, did it become the place that conceals the essential? When the vrātyas played in the sabhā, first with heaps of nuts, later with two dice, the winning throw was kṛta: a number divisible by four with nothing left over. After that came tretā and dvāpara; respectively the throws that gave remainders of three and two. The losing throw, kali, the “dogs throw,” was the throw that gave a remainder of one, the irreducible remainder. The names of these throws were then transferred to the different eras, or yugas: kṛta was the perfect age; kali the age of conflict and ruin, which continues to this day, ever more vividly prefiguring the “dissolution,” pralaya, the longer it goes on. Even when they divided up time into the calendar, they realized that there was always a remainder, an intercalary period that obliged them to make adjustments and new, more complicated calculations. The game, in which destiny is decided, and time: following these two trails, they reached a conclusion: one can only eliminate any residue in the realm of the discontinuous. The continuous, by contrast, is ever elusive. The discontinuous rests, drifts, on the continuous. Through the residue, the continuous forcibly reminds us of its existence. However subtly broken up, the discontinuous never quite manages to superimpose itself over the continuous. The difference is the surplus: that which must be sacrificed, in order for the equation, if only for a while, to come out. For a while: that is, until a new residue forms and is noticed. Obliging us once again to bow down before the continuous.

Something does get transmitted from one avatāra to another: a weak trace of the history that went before, the disaster that went before. The peculiarity of an aeon just concluded is passed on to the next aeon as a flavor, a tone, a veiled memory. Being ripens, is streaked, speckled, made anew with pieces that are already worn out. And much is lost. Something of Kṛṣṇa the negotiator, the military adviser of the Pāṇḍavas, ever absorbed in a plan obscure to all but himself, gets rubbed off on the prince of the Śākyas who left his home: the Buddha. Something unites them, even if the words they used were now so different, as likewise the things they did. Their detachment unites them. Their turning away from the fruit.

Following the Buddha, a throng of monks was approaching Vaiśālī. There were one thousand, two hundred and fifty of them. They were dumbstruck when the Buddha led them into the Park of the Mango Trees, a vast area of thick and silent woodland. The monks lined up between the plants, like schoolboys. They knew the Buddha liked to stay in parks not far from the towns, but not too near either, with plenty of entrances, not too busy by day, quiet at night. They had been to many others, given as gifts to the Buddha by sovereigns or merchants. But none possessed the subtle enchantment of the Park of the Mango Trees, this place where they entered as if into their own home, where only the odd ribbon or bead dropped along the paths showed that someone had passed that way before them.

Then the Buddha began to speak: “Monks, be ardent, perfectly conscious and attentive. Āmrapālī, the courtesan, is coming. Her beauty is without equal in the universe. Yoke your minds and do not produce false notions. The body is like a fire covered by ashes that a foolish man walks on.” Āmrapālī, Guardian of the Mango Trees, was mistress of the park. To spend a night with her cost fifty kārṣāpaṇas, equivalent to a value of five dairy cows. People had immediately whispered to her the news of the arrival of the Buddha and his monks. “The Buddha is staying here among my mangoes,” said Āmrapālī, thoughtfully. Her son, Vimalakauṇḍinya, offspring of a regal love, had left her to become a monk. “Now I will see,” Āmrapālī said to herself. She chose the finest clothes she had and ordered her pupils—there were five hundred of them—to put on their finest clothes. She set out at once in a welter of subdued murmurings. The procession penetrated the park like a dagger plunged to the speckled hilt. How often they had laughed together along those paths, among those trees.

The Buddha was finishing what he had to say to his monks. Āmrapālī got down from her carriage and bowed at his feet. The one thousand, two hundred and fifty monks lowered their eyes, to protect themselves. “Why have you come?” the Buddha asked Āmrapālī. “Because you are venerated in heaven,” said the courtesan. She had sat down on a stool beside the Tathāgata. The Buddha went on asking her questions. Did she like her work? “No,” said Āmrapālī. “The gods ordered me to do it.” “Who ordered you to gather together your five hundred pupils?” the Buddha asked. “They are poor girls, and I protect them,” said Āmrapālī. The Buddha said nothing. The silence was total. The ocher patches of the monks mingled with the colorful patches of the courtesans. “That’s not true,” said the Buddha in a soft voice. Āmrapālī bowed and said she wanted to become a follower of the Buddha. Then she felt she could say no more. She put the palms of her hands together in a sign of farewell and mustered up the courage to say one last thing: “My only desire is that the Buddha and the community of monks accept an invitation to my house.” Saying nothing, the Buddha accepted.

On their way back to Vaiśālī, Āmrapālī’s pupils, who couldn’t keep their voices down now, ran into another, even more sumptuous procession, made up of the Licchavis, the eminent families of Vaiśālī. They were going to meet the Buddha. Everyone stood to one side to let them pass. Not so Āmrapālī. Her carriage and the five hundred pupils behind it refused to move from the center of the road. The procession of courtesans collided with the procession of nobles. Wheel against wheel, hub against hub, Āmrapālī’s carriage pressed on, while others tumbled down the bank. In the melee, the courtesan brushed right past the angry faces of the Licchavis. They asked: “Why are you behaving like this?” “I’ve got to get back in time to prepare myself to receive the Buddha,” said Āmrapālī scornfully. Then they offered her all kinds of treasures to concede the honor of the invitation to them. “Why should I accept?” said Āmrapālī. “Perhaps I shall be dead before tomorrow morning. I would only accept if the Buddha were to remain among us forever.” And she ordered two of her pupils to whip the oxen pulling her carriage.

Having finally reorganized themselves, the Licchavis reached the Buddha. The dignitaries got down from their carriages. Their servants stood behind them. They bowed and lay their gifts at the Buddha’s feet. The Licchavis women followed, heaping up precious fabrics. The Licchavis asked the Buddha to do them the honor of letting them invite him. The Buddha answered: “Āmrapālī has already invited me.”

Veṇuvana, Jetavana, Āmravaṇa, Kalandakanivāpa: these names punctuate the uniform, uneventful life of the Buddha, his dusty progress from place to place, begging bowl in hand. They are enameled islands, quiet paddocks furrowed by trickling streams. It was here that the Buddha loved to talk to his monks. None was more dear to him than the place he stayed last of all, Āmravaṇa, the Park of the Mango Trees, the most enchanting of all Vaiśālī’s seven thousand, seven hundred and seven parks. Āmrapālī begged the Buddha to accept it as a gift, out of pity for her.

Ānanda was the Buddha’s cousin. In his name we find “joy” (ānanda), a promise of happiness. He was preparing for his marriage to Janapadakalyāṇī when, together with six other young nobles of Kapilavastu and the palace barber, Upāli, he ran off to join the Buddha’s disciples. For twenty years he followed him, anonymous among the other faithful. Then the Buddha named him as his servant. From then on, for the next twenty-five years, they were never apart. Ānanda mended the Buddha’s cloaks. He went to find water for him. He introduced visitors. It is said he listened to eighty-two thousand statements of the Buddha. A further two thousand were told him by others. He came to be called Bahuśruta, “He who has heard much.” But he remained a “white robe,” never took ordination, like a student forever on the way. Later he would be severely reproached for this. He kept no account of the mind’s states and conquests, unlike many of those around him. One supreme privilege, denied to all the others, was enough for him: the constant company of the Buddha, for he was the only one who could see him all the time. The only one who stayed with him during those long periods when the monks would split up into small groups, scattered around desert places, with only the pelting of the rain for company as they awaited the Buddha’s return.

No one knew the Buddha as well as Ānanda did. Often he said nothing at all. “Was not the Buddha the Master? What need was there for me to speak?” he would say one day in his defense. All the same, he could be pushy too. More than once he had seen how the Buddha might refuse something twice and then agree at the third time of asking. Ānanda was accused, among other things, of having taken advantage of this. It is thanks to Ānanda’s insistence that women were admitted to the Order. “The doctrine would have lasted a thousand years, now it will only last five hundred,” said the Buddha on that occasion. But he did agree.

Ānanda never worried about always being on the way, because he was next to the Buddha, and he thought that for this reason alone he was nearer to the goal than anyone else. If others claimed to have reached it, what did that matter? It was better to be continually on the brink. This thought that had so long consoled him, filled him with terror when the Buddha told him that he would be dead three months hence. Ānanda wept. “I’m not ready yet, I never will be. And if I’m not ready living near the Buddha, how can I ever be when he is gone?”

It is true that Ānanda sometimes took advantage of his proximity to the Buddha. He could pass quite suddenly from his habitual silence to a petulant wheedling, of the variety he had seen other monks indulge in. On these occasions he was possessed by a demon who shook him like a puppet. One day he questioned the Buddha about what had happened after death to twelve people he had known. The Buddha gave prompt answers about each of the people concerned. He explained when they were to be reborn, how many times, and in what form. He was as calm as ever. Then he added: “Ānanda, it is not an unusual thing for a man to die. If you go asking questions of the Tathāgata every time a man dies, the Tathāgata will wind up a weary man. I had better reveal to you a chapter of the doctrine that will allow you to work out on your own what we can expect after death.” As the Buddha talked on, illustrating this new chapter of the doctrine, Ānanda’s mind was clouded by an immense sense of shame. The Buddha’s words flowed over him and evaporated into the air. He could never remember them.

Ānanda looked up at the Buddha and asked him the question he had been putting off for days and days: “How can awakening come about?” The Buddha was tracing signs on the ground with a stick. He went on doing so. In a flat voice he said: “In many ways. Looking at a peach blossom. Hearing a stone strike bamboo. Hearing the drum announcing dinner. Walking on a bamboo stick. Looking at the forest and the mountains. Looking at yourself in a barber’s mirror. Falling to the ground in a cloister. Tying a noose around your neck. Pouring water on your feet and watching it being soaked up by the dry earth.”

The Buddha once said that Ānanda was like a house that leaked when there was a storm. The water that got in was women. The image of the delightful Janapadakalyāṇī, left behind in Kapilavastu, would come to him from time to time, when he was preparing the Buddha’s bed or meditating or going to look for water, and bring on the sharpest of pangs. They left him exhausted and vulnerable. The Buddha reminded him of their previous lives when Ānanda was an ass, Janapadakalyāṇī a she-ass, and the Buddha their master—a poor peasant who would goad them on from time to time with a stick. Such subtlety wasn’t enough. So the Buddha took Ānanda like a baby and flew up into the sky, showing him an immense forest fire. He pointed to the disfigured body of a monkey on a charred trunk. Ānanda looked away. They flew on. In some heaven or other—and how was Ānanda supposed to know which?—in a noble but abandoned palace, they saw a marvelously shapely Apsaras looking into the void. “She’s waiting for you,” the Buddha said. They flew on. They saw five hundred amazingly beautiful Apsaras. “Beautiful, aren’t they?” said the Buddha. “Janapadakalyāṇī looks like a monkey in comparison,” said Ānanda. “You’ll have them all,” said the Buddha. Then he added: “But for the moment you mustn’t leave the monks.” Ānanda wasn’t sure whether he had been rewarded or humiliated. In silence they flew back down through the heavens.

The Buddha knew Ānanda was wavering and vulnerable. He watched him from the corner of his eye as he busied himself with the chores. A feverishness in Ānanda’s eyes betrayed his turmoil. There was a witch’s daughter who was mad about Ānanda. She asked her mother to throw some brilliant arka flowers on a brazier to attract him. Ānanda left the other monks like a sleepwalker. More than a woman, it was a flower he was following. A fog hid the rest.

Then the Buddha was forced to resort to the satyavākya, the “word of truth.” He wasn’t pleased that the absolute of the truth must come up against a sorcerer’s spells. Of course the true word would win, but it would be diminished by the clash. Truth does not compete with facts. Truth is not a tool. But the Buddha wanted to win Ānanda back. One evening, he saw him returning to the monks. He looked like a mule with saddle sores. Without a word he fell to the ground and slept for a long time.

“And women?” said Ānanda. “Don’t look,” said the Buddha. “But what if we see some?” said Ānanda. “Don’t say anything,” said the Buddha. “What if we do speak?” said Ānanda. “Be vigilant,” said the Buddha.

That life is “sweet” (madhura, deriving from madhu, “honey”) the Buddha announced when he was eighty years old, a few days before dying. It was the beginning of the rainy season. The Buddha said to his monks: “Split up and go your ways. Go wherever you have friends, in small groups. The land is prosperous toward Śalavatī. Around Vaiśālī there is famine. I will stay here with Ānanda. He will look after me.”

When they were alone, the Buddha was afflicted by a violent bout of sickness. He felt pains all over his body. Ānanda was in a state of constant agitation. Two questions echoed over and over in his confused mind: “What if the Buddha is utterly extinguished now? If the community is left without instructions?” All at once he realized he had asked the questions out loud. The Buddha replied: “What more can the community expect of me? I preached the doctrine without holding back.” And what he meant was, the esoteric no longer exists. Everything has been declared. All you have to do is listen. He went on: “I’m an old cart, vainly held together by thin belts. But even the diamond bodies of past Buddhas melted away. Even the gods of unconsciousness, who live for many kalpas, for millions and millions of years, die one day. Therefore, Ānanda, you must all stay on your islands, in your retreats—the islands and retreats of the doctrine.”

As soon as he was feeling better, the Buddha told Ānanda that he wanted to go back and see a few places near Vaiśālī that were dear to him. They reached a clearing that opened out toward a vast horizon. The Buddha asked Ānanda to stop. He had pains in his back again. Ānanda laid out the Buddha’s mat under a mango tree. Then he sat down next to him. The Buddha looked into the distance. He said: “Splendid and many-colored is the Island of the Jambū, and sweet the life of men.” They went down to Vaiśālī, to ask for alms. As they were leaving, the Buddha turned back, to his right. With elephant’s eyes, he looked at the city gate and smiled. “Why are you smiling?” asked Ānanda. “In twenty-five years I have never seen the Buddha turn to a city gate and smile.” “If a Buddha turns back and smiles, it must mean something. This is the Tathāgata’s last look at Vaiśālī,” said the Buddha.

There were three times in those last days when Ānanda omitted to ask a question. He did not ask the Buddha why man’s life is “sweet.” Another day, the Buddha three times remarked: “The interior of the Island of the Jambū is very pleasant.” Ānanda said nothing. Finally, shortly after the Buddha was feeling better, Ānanda heard him talk about the four “bases of magical powers” (ṛddhipādas), which, if developed, allow one to live for a whole kalpa, a whole cosmic cycle. Then the Buddha had added: “The Buddha now possesses those powers. Could he not, then, live for as long as the kalpa lasts? It would bring great good to the world, and the shadows would disperse. Gods and men would achieve peace.” Stubbornly, eyes steadily staring, Ānanda said nothing. It was his great, perhaps his only crime, certainly the only one he was reproached with, not just by the community of monks but by the Buddha himself. If at that critical moment Ānanda had asked the Buddha to exercise his powers and stay for a whole cosmic cycle, the Buddha would have stayed.

But why didn’t Ānanda say anything? He was possessed by Māra, who had ensconced himself in his belly. It was out of spite that Ānanda did not speak. “You did not grasp the sense of my words because you were possessed. I saw two horns on your head. Why did you let Māra get into your belly?” the Buddha asked him some time afterward. Those words buried themselves forever in Ānanda’s mind. Later, when he found himself alone before the monks, his inquisitors, still dressed in white before that huge splash of ocher robes, Ānanda admitted that he had been possessed by Māra. But then he added: “If the Buddha had stayed in the world for a whole kalpa, how could the Buddha Maitreya, who is to come after him, the venerable perfect one, ever appear?” Silence reigned among the holy gathering. Ānanda waited, terrified. A voice was raised: “Go back to your place. Repeat in their entirety the words you heard from the Buddha.”

That the compound disintegrate after eighty years or after three thousand was a matter of no importance to the Buddha. What matters is that the compound does disintegrate. Even the diamond Bodhisattva had disintegrated. So it was out of provocation that the Buddha let slip those words Ānanda would forever regret not having taken him up on: “There are those who have developed the four bases of magical powers (ṛddhipādas) and can live for a whole kalpa. I have developed them.” Ānanda said nothing. Was he distracted, confused? Or did he keep silent out of an excess of zeal? Or great wisdom? If Ānanda had asked the Buddha to exercise his powers, the world would have benefited immensely. But in so doing Ānanda would have shown that the important thing for him was the Buddha’s presence, not the truth of the doctrine, according to which it is irrelevant when a compound disintegrates, the crucial point being that the compound does disintegrate. By not asking the Buddha to stay—something that seemed the greatest of crimes to the monks and to himself—Ānanda had been faithful, perhaps too faithful (but can one ever be too faithful?) to the doctrine.

These were the Buddha’s last days. The Tathāgata said: “When I am no longer here, the monks can be happy even if they do not observe the lesser and least important of the rules.” Ever beside him, Ānanda said nothing. This was the moment in which the history of Buddhism was decided. Why didn’t Ānanda immediately ask the Buddha to specify which were “the lesser and least important of the rules.” When the implacable Mahākāśyapa—and the four hundred and ninety-nine monks meeting in the council of Rājagṛha—asked him to explain this omission, Ānanda said: “I didn’t want to pester the Buddha.” Yet he had pestered him so many times before … Now, as a result of that omission, the monks were obliged not to follow the Buddha’s advice. Had they announced that they were choosing not to observe “the lesser and least important of the rules,” everybody would immediately have said that the Order was degenerating, that now that the Master was gone, the monks were taking things easy And how could they decide on their own which rules were “the lesser and least important” ones? The sixth and the ninth, in a list of rules? Or the fourth and the seventh? Or just the twelfth? Who could decide that? Ānanda observed a sad silence.

“But,” they went on, “if we obey all the rules just as they are, we will still be acting against the Buddha’s will. We will never know the happiness that he allowed us to glimpse when freed from the ‘lesser and least important of the rules.’ ” There was no way out. They decided they would go on following all the rules the Buddha had given them with equal zeal, even the ones that might seem obscure and irrelevant. Thus an invisible burden weighed on the monks. Sometimes they thought of that lightness that they would never now be able to achieve.

After the Buddha’s funeral there was a stasis in the air. A dull curtain was drawn across everything. The community of monks were looking to make a gesture. They wanted a scapegoat, someone to punish. Among the hundreds of ocher robes, one white robe stood out: Ānanda. He who had heard more of the Buddha’s teaching than anybody else, who knew the doctrine like the palm of his hand. He who had failed to persuade the Buddha to stay alive. He who had omitted to ask him to stay at the right moment. Omission: what crime could be worse? Every gesture can be redeemed by the mental state in which it is made. But omission is a defeat of the mind, makes a mockery of vigilance, which should be constant, always. “It didn’t occur to me,” Ānanda blurted out, with that effrontery which so exasperated the older monks, when they began to question him.

Four hundred and ninety-nine monks were arranged in a semicircle. Before them stood Ānanda, alone. In the center of the semicircle was Mahākāśyapa, the chief inquisitor. He had not witnessed the great events of the Buddha’s life. He was the last of the latecomers, but he came from farther away than the others. With the Buddha gone, the monks had been seized by the frenzy to follow him. They thought: “When the great elephant goes, the little ones follow him.” Mahākāśyapa stopped them with a voice that demanded obedience: “Monks, do not go! It is imperative that we all unite to prevent the Law from falling into ruin.” Then he sounded the gong to summon everybody to a gathering. And he warned the monks: “Before composing the supreme meaning, you must not give up life for extinction.” Now he was presiding over the assembly. He called Ānanda a “mangy jackal.” No one objected.

• • •

Gathered together at Rājagṛha, the monks reminded Ānanda that with his stubborn impudence he had always been one for the women, right to the end, as though in complicity with them. After his death, the Buddha’s feet, like the rest of his body, had been coated with gold. Yet the tears of some unknown woman had turned them white, as if the liquid of suffering were corrosive. It was Ānanda who had allowed this outrage.

And there was another, even more scandalous episode. Surrounded by a group of women, Ānanda had lifted the robes of the dead Buddha, thus revealing his phallus. Now everybody knew that the Buddha’s phallus was like that of those stallions with hidden testicles—or at least so it ought to have been to conform with the thirty-two lakṣaṇas, or “tokens” of perfection. But how dare Ānanda expose it to the adoration of those bigoted, or perhaps incredulous women? When they reproached him with this crime, Ānanda muttered something about the “nakedness of the Buddha.” But no one was convinced. Alone among the monks, even after the Buddha’s death, even in a now empty world, Ānanda went on plotting with the womenfolk, in the teeth of all criticism.

The line of monks moved along the road to Rājagṛha. Lost in their midst was a restless Ānanda. His hair was gray, but there were still those who called him “boy,” kumāraka. He thought: “Among all these arhats, I feel like a still unweaned calf among big oxen. My studies are still not over.” Before him and behind him, heavy, purposeful footfalls. It was a very different business from when he had walked along with the Buddha and the forest closed behind them as if they had never passed. Now he felt like one particle in a swarm, only he wasn’t sure whether of friends or enemies. Perhaps they set such store on keeping him with them the better to enjoy the moment when they would throw him out.