ROOFLINES

Just as a book is judged by its cover, architecture is judged by its exterior shell. Within that shell, no structural feature is more important than the roofline, which accounts for 80 percent of exterior focal points, beating out cladding, landscaping, and windows. Angles and roofing materials indicate the character, integrity, and mystique of your home, and, by extension, yourself. Even the most rote prefab building takes on new relevance with a perplexingly angular roof.

The material used to shield your home from the elements is just as important as the slope of the roof. There are a baffling number of material choices to consider, along with the roofline’s pitch and profile, as well as how the roof will present within the surrounding environs. For instance, slate can read as either painfully old-fashioned or stunningly modern—it all depends on the execution. A green roof requires a flat surface; or does it? And asphalt is relegated to the realm of mediocrity. (That one isn’t up for discussion.)

In this secion we’ll survey and weigh the pros and cons of a wide range of materials, from seamed metal to organic thatching, along with a dynamic array of rooflines that will help you choose a building profile that balances the solidity of the structure with the depth of your design ethos and the vastness of the sky above.

Up on the Roof

If the home is a living, breathing organism, then the interior rooms would be the nucleus and the framing would be the protective membrane. Just as a cell’s shape dictates its movement, purpose, and reactivity, the angle and pitch of your home’s roof will determine its place in the architecture continuum. Basic, high-pitched double-gable houses are legion; venture outside the box-within-a-box thinking that is so pervasive in contemporary architecture theory and choose a profile that conveys your individuality and disdain for social norms.

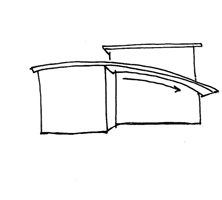

CURVED

An arched roof creates visual interest both indoors and out. For environmental credibility and elemental harmony, match the curve to the gentle undulations of the earth around the surrounding property. Alternatively, a modern home with a curved roof situated on a plateau makes for an unexpected counterpoint to the flat land. The curved roof is rooted in traditional Asian architecture, where it was finished with clay tiles; achieve maximum impact today by executing in white rubber. The roof pitch is almost nonexistent.

GABLE

It should be noted that the gable roof is included only for reference. The style is to be avoided at all costs. No amount of plywood, concrete, steel, or vintage Knoll furniture can diminish the inherent and depressing conventionality. The roof pitch is pretty extreme.

FLAT

Historically, flat roofs were only used on sheds and other uninhabitable structures, as they tend to leak and are prone to collecting standing water. Despite the obvious and inherent design challenges (and health concerns), modernist architects have embraced the look whole-heartedly and today most modern homes flaunt a flat roof. Generally, these roofs are only suitable for temperate climates, as the horizontal plane collects snow and debris in regions with harsh winters. Nonetheless, modernist aesthetics trump Mother Nature, and the flat roof can now be found in nearly every climate. There is no roof pitch.

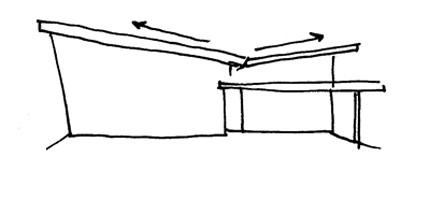

BUTTERFLY

Inverted at the center of the building, the middle sits lower than the top. This roofline is most sought after because it is the exact opposite of a traditional roof with a central peak. In addition, the dip in the midpoint creates dramatic ceilings on the interior, which can be uplit to create an isolating and visually challenging room. The style is nearly synonymous with midcentury houses erected in California communities such as Palm Springs, but has been reclaimed by contemporary designers all over the world. There is a negative roof pitch.

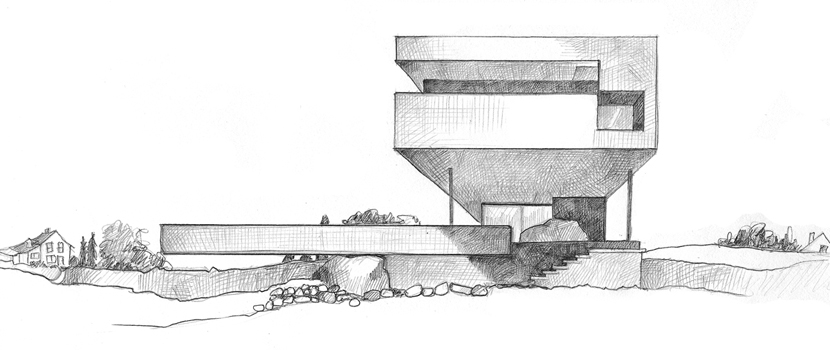

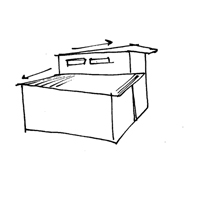

BI-LEVEL

The roof of a bi-level sits on two separate floors. Originated by Frank Lloyd Wright, the lower surface of this design doubles as a perch for observing neighbors without actually descending to the pedestrian sidewalk. It’s an excellent alternative for those unable to commit to a flat roof. Bi-levels are best suited to houses that face a busy street, as the elevation is focused on the front with little decorative interest on the rear. The roof pitch is extremely low.

CASE STUDY #71

“Watering the frozen lawn had become his only release from the sameness of his suburban neighbors.”

If order and logic are in the architecture, then architecture will inevitably complement nature.

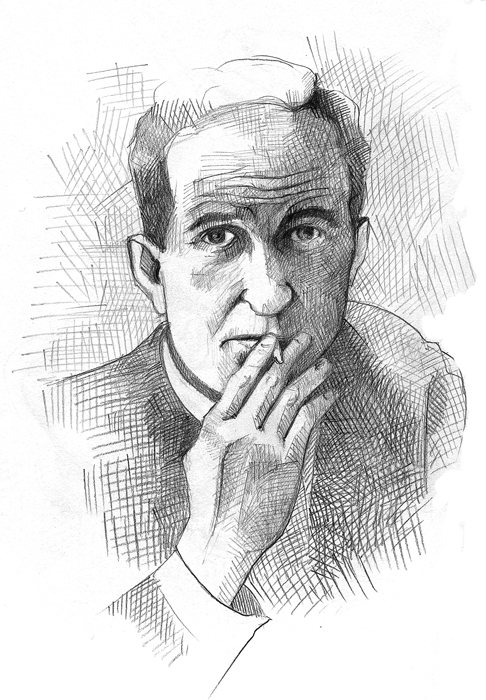

CRAIG ELLWOOD (1922–1992)

A true American hustler, Ellwood was born Jon Nelson Burke. After leaving the army, he and his brother set up a building company called “Craig Ellwood,” the name of which they borrowed from a nearby liquor store of the same name. He took a few classes in structural engineering and then opened his own firm. He sold clients on his vision and then got licensed architects in his employ to do the actual design. With his skills for promotion, he managed to fuse the style of Mies van der Rohe with laid-back California bungalows.

Notable Works: Art Center College of Design, Pasadena. South Bay Bank, Los Angeles.

Notable Works: Art Center College of Design, Pasadena. South Bay Bank, Los Angeles.

Shingle Style

As we learned in the previous section, a flat roof is ideal. It makes a perfect base for seeding a grassy knoll: the illustrious “green” roof. However, if a flat roof isn’t possible, it’s imperative that the material used to sheath the roof is in keeping with the overall modern aesthetic of the home and its environs. Many designers advise taking a tour of the neighborhood to determine which roofing material will best fit in with the look of neighboring houses. We suggest taking that same tour, but with a different goal. Once you’ve compiled a short list of the most common roofing materials, choose something completely different, the polar opposite if possible, to ensure that your house has individuality, delivers visual impact, and reflects your triumphant journey from mediocrity to modernity.

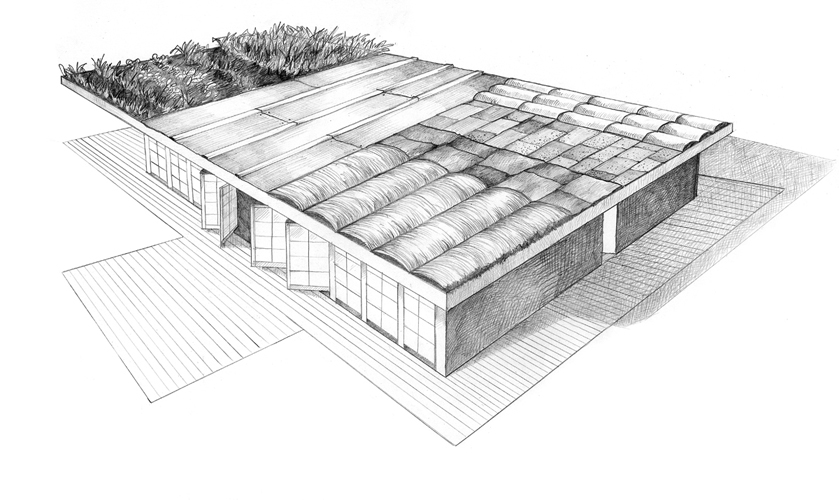

1. SOD

The concept of a green roof may seem modern, but the practice of growing vegetation on top of roofs dates back thousands of years, perhaps even before recorded history. The sod roof of yesteryear was a way to hold together the sheets of bark that composed the inner roof. The sod roof of today is purely decorative.

PROS: Vegetation growing on the roof signifies a certain cultural and environmental awareness and brings with it a delightful self-satisfaction. Plant your green roof with clover, knotweed, and something fragrant, like mint. See Natural Selection for more recommended species.

PROS: Vegetation growing on the roof signifies a certain cultural and environmental awareness and brings with it a delightful self-satisfaction. Plant your green roof with clover, knotweed, and something fragrant, like mint. See Natural Selection for more recommended species.

CONS: None.

CONS: None.

2. METAL

Metal roofs have been around for hundreds of years and feature a wide variety of materials from copper to zinc. Tin tiles became popular in the nineteenth century. However, for your purpose, the only metal roof is standing seam. These are sheets of steel that are punctuated with raised vertical lines. They are manufactured on-site, with each sheet crimped together at the seam to ward off rain, snow, het cetera.

PROS: Extremely durable and gorgeously minimalist, a metal roof can last up to fifty years.

PROS: Extremely durable and gorgeously minimalist, a metal roof can last up to fifty years.

CONS: Provides a steel-drum-style background noise during inclement weather.

CONS: Provides a steel-drum-style background noise during inclement weather.

3. THATCH

Dry vegetation such as reeds, straw, and heather is thickly layered over an inner roof to protect it from the elements. This is an incredibly old technique, and examples can be found everywhere from sub-Saharan Africa to the United Kingdom, where many pasty pub crawlers with troubled teeth still lay their heads under a thatched roof.

PROS: Unlike contemporary counterparts, a good thatching can last half a century. It hasn’t taken off in hip modernist circles; if you’re a gambler, installing a thatch roof may make you a trendsetter.

PROS: Unlike contemporary counterparts, a good thatching can last half a century. It hasn’t taken off in hip modernist circles; if you’re a gambler, installing a thatch roof may make you a trendsetter.

CONS: Unfortunately, the look is incongruent with contemporary architecture and almost guaranteed to raise eyebrows at city building permit offices.

CONS: Unfortunately, the look is incongruent with contemporary architecture and almost guaranteed to raise eyebrows at city building permit offices.

4. ASPHALT

Almost every roof on every single-family home in North America is clad with the ubiquitous asphalt shingle. Made from a base of composite materials (ranging from fiberglass to wood pulp), it is soaked in an asphalt mixture (sticky liquid derived from crude oil) which is embedded with shards of rock.

PROS: None.

PROS: None.

CONS: These shingles off-gas something wicked and aren’t even close to environmentally friendly. Many companies offer collections that mimic the look of slate or wood shingles, even in a putrid green (meant to mimic what exactly?), but overall asphalt denotes suburbia.

CONS: These shingles off-gas something wicked and aren’t even close to environmentally friendly. Many companies offer collections that mimic the look of slate or wood shingles, even in a putrid green (meant to mimic what exactly?), but overall asphalt denotes suburbia.

5. CLAY TILE

Rarely seen on houses in the Northeast, clay tiles are most popular in temperate climates, such as California and Florida, where they cover even the most tragic tract homes. The use of clay tiles for roofing goes back twelve thousand years, with most examples employing a long tile with a curved butt that was fitted into another tile to create a tessellated surface. Clay tiles fell from fashion in the nineteenth century, when metal roofs (which were easier to install and maintain) became popular.

PROS: None. Except they’re sort of sustainable, or at least recyclable.

PROS: None. Except they’re sort of sustainable, or at least recyclable.

CONS: Metal is better, and besides, clay roofs are synonymous with faux Tuscan villas in gated golf course communities.

CONS: Metal is better, and besides, clay roofs are synonymous with faux Tuscan villas in gated golf course communities.

6. SLATE

There is evidence that some settlers in the New World used slate to cover their homes, but quarrying and transporting the material was so costly that the practice wasn’t common.

PROS: Noncombustible and lasts up to two hundred years.

PROS: Noncombustible and lasts up to two hundred years.

CONS: This natural stone is superheavy and expensive, and is more likely to be seen on a Tudor Revival than a contemporary modular home. Also crazy expensive.

CONS: This natural stone is superheavy and expensive, and is more likely to be seen on a Tudor Revival than a contemporary modular home. Also crazy expensive.