Chapter 7

The Inquisition Trial

(1632–1633)

Complaints about the Dialogue

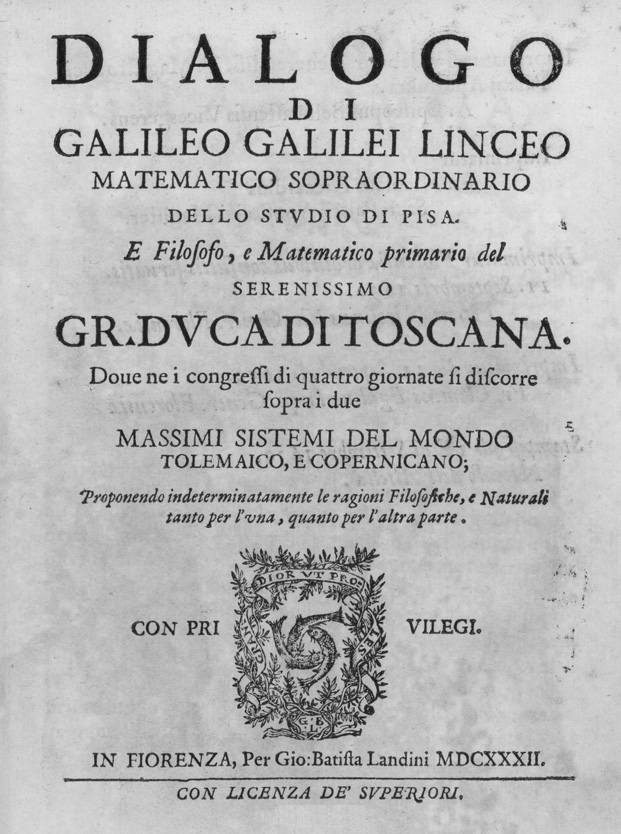

Galileo’s Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems, Ptolemaic and Copernican was published in Florence in February 1632. It was well received in scientific circles. But a number of rumors and complaints began emerging and circulating among clergymen and officials, especially in Rome.

The most serious complaint was that the book violated a precept issued by the Inquisition to Galileo in 1616; this was the special injunction to stop holding, defending, or teaching the Earth’s motion in any way whatever. Recall that the Inquisition proceedings contain a notary memorandum dated February 26, 1616 which reads like a report of what happened on that day to implement the orders of Pope Paul V from the Inquisition meeting on the previous day. The document states that, first, Cardinal Bellarmine gave Galileo the informal warning to abandon Copernicanism (that is, to stop holding or defending the Earth’s motion as true or as compatible with Scripture); and immediately afterwards, Commissary Seghizzi issued Galileo the formal injunction. The charge was that Galileo’s just published book was a clear violation of this special injunction, for, whatever else the book did, and however else it might be interpreted, it undeniably taught, supported, and defended the Earth’s motion, at least as a hypothesis; this transgression was aggravated by the fact that he had not disclosed this injunction to the officials who authorized the book’s publication, and so he could also be accused of deception.

To be sure, the memorandum did not bear Galileo’s signature, and this alone was suspicious. In fact, as we know from our earlier discussion, the factual accuracy of this document and the legal validity of the precept were questionable, since they conflict with all other documents and events. However, in 1632, some of these other documents were unknown or unavailable, and in any case such anti-Galilean critics had not noticed any conflicting evidence, but focused on this particular incriminating item. Under different circumstances such legal technicalities could have been taken seriously. However, too many other difficulties were being raised about the book.

One of these other difficulties was that the book only paid lip service to the stipulation about a hypothetical discussion, which represented Pope Urban’s (and Bellarmine’s) compromise. In reality, the book allegedly treated the Earth’s motion not as a hypothesis, but in a factual, unconditional, and realistic manner, as a factual possibility or probability about physical reality.

This was a more or less legitimate complaint. But the truth of the matter is that the concept of hypothesis was itself ambiguous at that time and in that context.1 By hypothetical discussion, Urban meant treating the Earth’s motion merely as an instrument of prediction and calculation, rather than as a potentially true description of reality. On the other hand, Galileo took a hypothesis to be an assumption about physical reality, which accounts for what is known, and which may be true, though it has not yet been proved to be true.

Then there was the complaint that the book did not show the proper appreciation of divine omnipotence. Remember that this was the basis of Pope Urban’s favorite (and allegedly irrefutable) argument against the Earth’s motion, and that Galileo had complied with the request to include this argument in the book. The charge was that the argument is uttered by Simplicio, who is allegedly a fool, while the other two speakers do not express a sufficiently favorable assessment of the argument; and that the argument is not prominently displayed in the book insofar as it occurs in a passage (on the last page) that is hard to find and easy to miss.

As I pointed out earlier, Galileo did genuinely (and correctly) believe that there was something right about the divine-omnipotence argument. Aspects of some formulations of the argument are correct, insofar as they reflect the logic and methodology of theoretical explanation, which Galileo discusses in other passages. However, other formulations are easily answered, for example, by pointing out that a corresponding objection applies to the geostatic world view as well. The root problem was that Galileo’s book was also supposed to steer clear of theological discussions, and so on this topic he did not have viable options. This charge, then, was a plausible but debatable one.

There were also complaints involving alleged irregularities in the various permissions to print which Galileo obtained. For example, besides displaying the imprimatur for the city of Florence, the printed book displayed an imprimatur for the city of Rome. In fact, originally he had planned to have it published in Rome, but then there was an unavoidable change of venue, due partly to the death in 1630 of Galileo’s patron, Prince Federico Cesi, founder and head of the Lincean Academy, who was going to sponsor its publication. The change was also due to an outbreak of the plague in 1630–2, which made it almost impossible for the book manuscript to be sent back to Rome, after Galileo had returned home to Florence.

To add to all this, there were substantive criticisms of various specific points discussed in the book. Feelings had been hurt by some of Galileo’s rhetorical excesses and biting sarcasm, and malicious slanders circulated, suggesting that the book was in effect a personal caricature of the pope himself. One of these slanders stemmed from Pope Urban’s favorite argument, the divine-omnipotence objection to Copernicanism, being put in the mouth of Simplicio. Aside from the alleged failure to appreciate divine omnipotence, as we saw above, Galileo was thought to be insulting Pope Urban by portraying him as a simpleton.

This complaint could be cleared up by pointing out that “Simplicio” was also the Italian name of the sixth-century Aristotelian philosopher Simplicius. Galileo himself had so stated in the book’s preface. Moreover, it would be natural and rhetorically proper to have Simplicio advance the divine-omnipotence objection, given that he is the interlocutor who defends Ptolemy and criticizes Copernicus.

Another malicious slander involved the image printed at the bottom of both the book’s frontispiece and the title page (see Figure 18). It depicts three fishes in a circular pattern, with the mouth of each fish touching the body of another. One rumor insinuated that this image was mocking the pope’s widely criticized “nepotism.” In fact, Urban had carried this practice to new heights by appointing several relatives to important positions: his brother Antonio Barberini, Sr., as cardinal, and eventually as secretary of the Inquisition; his nephew Francesco also as cardinal, and eventually as secretary of state; his nephew Antonio, Jr., also as cardinal; and his nephew Taddeo as governor of the city of Rome. Fortunately, this particular slander was easily and conclusively refuted when it was demonstrated that the image of the three fishes in a circular pattern was the long-standing logo of the book’s publisher, which usually appeared in all the books it printed.

Figure 18. Title page of Galileo’s Dialogue

The sheer number of complaints, and the seriousness of some of the charges, were such that the pope might have been forced to take some action even under normal circumstances. But Urban VIII was himself in political trouble due to his behavior in the Thirty Years’ War between Catholics and Protestants (1618–48). Given his especially vulnerable position, not only could Urban not continue to protect Galileo, but he chose to use Galileo as a scapegoat to reassert, exhibit, and test his own authority, power, and religious credentials.

In the summer of 1632, sales of the Dialogue were stopped, and unsold copies confiscated. The pope did not immediately send the case to the Inquisition, but took the unusual step of first appointing a special commission to investigate the matter. This three-member panel issued its report in September 1632,2 and it listed as areas of concern about the book all of the above-mentioned problems, except one—the slander about the image of three fishes, which by then had already been refuted. In fact, it is from the commission’s report that we learn about all these complaints that had been accumulating since the book’s publication. In view of the report, the pope felt justified in forwarding the case to the Inquisition.

Yet the report can also be read as leaving open the question of whether to prosecute Galileo, or merely have him revise the Dialogue. So perhaps Urban wanted to convey the impression that the report was unequivocal in recommending prosecution, which is what he said to the Tuscan ambassador to Rome. In other words, it is likely that Urban was mostly manipulating the proceedings, for various reasons. In part, he was probably trying to cover up his own permissivism and complicity in the writing and publication of the Dialogue.3 Urban may also have been acting on his perception that this book came close to formal heresy by its failure to treat the Earth’s motion hypothetically and show the proper appreciation for divine omnipotence; however misconceived and incorrect this perception was, it appears to have been genuinely and sincerely felt by Urban.4 So Galileo was summoned to Rome to stand trial.

Proceedings Begin

The entire autumn of 1632 was taken up by various attempts on the part of Galileo and the Tuscan government to prevent the inevitable. The Tuscan government got involved because of Galileo’s position as Philosopher and Chief Mathematician to the grand duke, because the book contained a dedication to the grand duke, and because the grand duke had been instrumental in getting the book finally printed in Florence.

At first, they tried to have the trial moved from Rome to Florence. This request was summarily rejected by the Inquisition, because of the seriousness of the charges and the notoriety of the person involved. Then they asked that Galileo be sent the charges in writing, and that he be allowed to respond in writing. The reply was that the Inquisition did not operate in such a manner. As a last resort, three physicians signed a medical certificate stating that Galileo was too ill to travel. This was basically true: he was 68 years old, physically frail, and afflicted by his share of ills; moreover, the recent outbreak of the plague meant that travelers from Tuscany to the Papal States were subject to quarantine at the border, and this would have been exhausting for such an ill old man. The medical excuse was also rejected. In fact, at the end of December, the Inquisition sent Galileo an ultimatum: if he did not come to Rome of his own accord, they would send officers to arrest him and bring him to Rome in chains.

On January 20, 1633, after making a last will and testament, Galileo began the journey. (I leave it to your imagination to speculate what the connection may have been between these two new-year’s resolutions.) Because of an eighteen-day quarantine at the border, the 173-mile trip took 24 days.

On his arrival in Rome, Galileo was not placed under arrest or imprisoned by the Inquisition, but was allowed to lodge at the Tuscan embassy (Palazzo Firenze). However, he was ordered not to socialize and to keep himself in seclusion until he was called for interrogations.

These were slow in coming, as if the Inquisition wanted to use the torment of the uncertainty, suspense, and anxiety as part of the punishment to be administered to the old man. It was very much in line with one reason mentioned earlier by officials as to why Galileo had to make the journey to Rome, despite his old age, ill health, and the epidemic of the plague: it was an advance partial punishment or penance, and if he did this the inquisitors might take it into consideration when the time of the actual proceedings came.

The first interrogation was held on April 12. In accordance with standard Inquisition practice, this hearing was held at the Inquisition palace, in the office of the commissary, who at that time was Vincenzo Maculano;5 also present were the assessor, the prosecutor, the notary, and one or two assistants. The questions did not focus on Pope Urban’s complaint about the book’s failure to treat the Earth’s motion hypothetically and to appreciate divine omnipotence, but rather on the events of 1616. In answer to various questions, the defendant claimed three main things.

Galileo stated that in February 1616 Cardinal Bellarmine had given him an oral warning, prescribing that the geokinetic theory could be neither held nor defended as true or compatible with Scripture, but only discussed hypothetically. However, Galileo denied having received from the Inquisition Commissary Seghizzi a special injunction not to hold, defend, or teach the Earth’s motion in any way whatever; as supporting evidence, he introduced a copy of the certificate which Bellarmine had written for Galileo in May 1616, which said nothing about Seghizzi’s injunction. Galileo’s third main claim was made in answer to the question why, in light of Bellarmine’s warning and/or Seghizzi’s injunction, he had not obtained any permission to write the book in the first place, and why he had not mentioned them when obtaining permission to print the book; these omissions had angered the pope and had made him feel deceived. Galileo answered that he had not done so because he only knew about Bellarmine’s warning, and the book did not really hold or defend the Earth’s motion, but rather showed that the arguments in its favor were not conclusive, and thus it did not violate that warning.

This was a very strong and viable, but not unproblematic, line of defense. Bellarmine’s certificate clearly surprised and disoriented the Inquisition officials. But the issue now became whether Galileo’s book violated Bellarmine’s warning by defending the truth of the geokinetic theory.

From this point of view, it could be argued that in the book, despite its dialogue form, repeated disclaimers that no assertion of Copernicanism was intended, the inconclusive character of the pro-Copernican arguments, and the presentation of the anti-Copernican and pro-geostatic arguments, it was readily apparent that the pro-geostatic arguments were being criticized and the pro-Copernican ones were being assessed favorably. Thus, it could be said that the book was arguing in favor of the truth of Copernicanism, and hence was defending it. This in turn meant that, even from the point of view of Bellarmine’s informal warning to Galileo, the Dialogue was a transgression.

This complaint was more or less legitimate, but also questionable. For, in this regard, the issue was whether Bellarmine’s warning not to defend the truth of Copernicanism included a prohibition to evaluate the arguments, and whether such a prohibition was reasonable. Clearly, Galileo did engage in evaluation, besides presentation, interpretation, and analysis; and his evaluative conclusion was that the pro-Copernican arguments were much better than the anti-Copernican ones. But if his evaluation was correct, fair, or reasonable, could he be blamed for the result? In other words, one could say that the Dialogue was discussing, not defending, the Earth’s motion, insofar as it was a critical examination of the arguments on both sides; admittedly, although the pro-Copernican arguments were not conclusive, they were stronger than the anti-Copernican ones, but that was not Galileo’s fault.

Out-of-Court Plea-Bargaining

Bellarmine’s certificate was obviously new and crucial evidence that could not be ignored. Therefore, it took another two and one-half weeks before the Inquisition decided on the next step in the proceedings. In the meantime, Galileo was not allowed to return to the Tuscan embassy, where he had been lodging since his arrival in Rome in February; rather, he was detained at the Inquisition palace, but allowed to lodge in the chief prosecutor’s apartment. What the inquisitors decided was something very close to what might be called an out-of-court settlement involving a plea-bargaining agreement.

They would not press the most serious, but least provable, charge (of having violated the special injunction). Nor would they press the charge of having violated Urban’s request for a hypothetical treatment of the Earth’s motion and an appreciation of divine omnipotence. However, Galileo would have to plead guilty to the lesser charge of having transgressed Bellarmine’s warning not to defend the truth of Copernicanism, in regard to which Galileo’s defense, although viable, was the weakest. To reward such a confession, they would show some leniency toward such a lesser violation.

To work out this deal, the Inquisition asked three consultants to determine whether Galileo’s Dialogue taught, defended, or held the geokinetic theory; in separate reports all three concluded that the book clearly taught and defended the doctrine, and came close to holding it. Then the commissary general of the Inquisition talked privately with Galileo to try to arrange the deal, and after lengthy discussions he succeeded. Galileo requested and obtained a few days to think of a dignified way of pleading guilty to the lesser charge.

Thus, on April 30, the defendant appeared before the Inquisition officials for the second time, and signed a deposition stating the following. Ever since the first hearing, he had reflected about whether, without meaning to, he might have done anything wrong. It dawned on him to reread his book, which he had not done for the past three years, since completing the manuscript. He was surprised by what he found, because the book did give the reader the impression that the author was defending the geokinetic theory. This had not been his intention. Galileo attributed it to vanity, literary flamboyance, and an excessive desire to appear clever by making the weaker side look stronger. He was deeply sorry for this transgression, and was ready to make amends.

This admission spared Galileo more drastic punishments, which might have ended with being burned alive at the stake. Such a capital punishment was meant to be charitable to the defendant, by giving him one last chance to repent, and thus save his soul, before his body was consumed by fire. However, Galileo declined such charity; he did not want to contribute to the “publish and perish” tradition, so to speak.

After this deposition, Galileo was allowed to return to the Tuscan embassy. On May 10, there was a third formal hearing at which he presented his defense. He repeated his recent admission of some wrongdoing, together with a denial of any malicious intent, and added a plea for clemency and pity. The trial might have ended here, but was not concluded for another six weeks. The new development was one of those things that make the Galileo affair such an unending source of controversy, and such rich material for tragedy.

Threat of Torture

Obviously, the pope and the cardinals of the Congregation of the Holy Office would have to approve the final disposition of the case. Indeed, it was standard Inquisition practice for an official, the assessor, to compile a summary of the proceedings for the benefit of the cardinal-inquisitors. So a report was written, summarizing the events from 1615 to Galileo’s third deposition just completed.

Through a series of misrepresentations, this report left no doubt that Galileo had committed some kind of criminal act. On the other hand, by various quotations from the confessions and pleas in his depositions, the report made it clear that he was not obstinately incorrigible, but rather was sorry and willing to submit.

However, the report did not resolve the pope’s and the Inquisition’s doubts about Galileo’s intention. So, on June 16, at an Inquisition meeting presided over by Pope Urban, they reached several decisions.6 The defendant should undergo a so-called “rigorous examination”; that is, he should be interrogated under the verbal threat of torture in order to determine his intention. Even if his intention was found to have been untainted and pure, he had to recite an abjuration. He was to be condemned to formal arrest at the pleasure of the Inquisition, and the Dialogue banned.

Threat of torture and actual torture were, at the time, the standard practice of the Inquisition,7 and indeed of almost all systems of criminal justice in the world. Nevertheless, such an interrogation, together with the abjuration, the formal imprisonment, and the book ban were not really in accordance with the spirit or the letter of the out-of-court plea-bargaining and agreement. Galileo felt betrayed and always remained bitter about this outcome.

On June 21, Galileo was subjected to the formal interrogation under the verbal threat of torture. He did not undergo actual physical torture, since the papal decision had been only to use the verbal threat, and the Inquisition was scrupulous about such distinctions. Moreover, the Inquisition had rules and practices about torture, which it usually followed. These rules prohibited actual torture from being applied to those who were elderly or in ill health; and Galileo was both.

The result of the interrogation was favorable. For, even under such a threat, Galileo denied any “malicious” intention—i.e., he denied that his defense of the Earth’s motion had been intentional, in the sense of being motivated by a belief that the Earth moves; and he showed his readiness to undergo actual torture, and to die if need be, rather than admit to such an intention and belief.

Sentence

The following day, June 22, at a ceremony in the convent of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome, he was read the sentence and then recited the formal abjuration.

The sentence8 found Galileo “vehemently suspected of heresy.” The expression “vehement suspicion of heresy” was, as we saw earlier, a technical legal term which meant much more than it may sound to modern ears. The Inquisition was primarily interested in two main categories of crimes: formal heresy and suspicion of heresy. One difference between them was the seriousness of the offense; another was whether the culprit, having confessed to the incriminating facts, admitted having an evil intention. Furthermore, two main subcategories of suspicion of heresy were distinguished, vehement and slight, again dependent on the seriousness of the crime.

“Suspicion of heresy” was not, then, merely suspicion of having committed a crime, but was itself a specific category of crime. Galileo was in effect being convicted of an offense that was intermediate in seriousness, among those handled by the Inquisition.

The sentence mentioned not one but two main errors, or suspected heresies. The first involved holding a doctrine that was false and contrary to Scripture. The second involved assuming the principle that it is permissible to defend as probable a doctrine contrary to Scripture.

This two-fold character of Galileo’s suspected heresy is important. The first error concerned a doctrine about the location and behavior of natural bodies. Four particular theses were distinguished—heliocentrism, heliostaticism, geokineticism, and the denial of geocentrism; but the respective status of these four parts was not being censured in any more nuanced fashion. The second suspected heresy concerned a methodological, epistemological, theological, and hermeneutical principle, a norm about what is right or wrong in the search for truth and the quest for knowledge. It was a principle that declared Scripture to be irrelevant to physical investigation, and denied the authority of Scripture in natural philosophy (physics, astronomy, science).

Recall that these two suspected heresies were the main charges of which Galileo had been accused in 1615 by Caccini and Lorini. Thus, the sentence was presenting the condemnation of 1633 in part as a resumption of the proceedings temporarily suspended in 1616, and as confirmation of the essential correctness of those charges, now demonstrated by the publication of the Dialogue.

Furthermore, the methodological principle for which Galileo was being condemned was expressed in terms of probability: “that one may hold and defend as probable an opinion after it has been declared and defined contrary to the Holy Scripture.”9 This seems to add another level of nuance and prohibition to the ones we discussed earlier. Let me explain.

In our discussion of Galileo’s first confrontation with the Inquisition in 1616, we distinguished several orders to him regarding Copernicanism. There was Pope Paul V’s injunction not to discuss Copernicanism, intended to be issued in case Galileo would reject Bellarmine’s warning; it is clear that this order was never actually issued by the commissary to Galileo. Then there was Commissary Seghizzi’s precept not to hold, defend, or teach in any way the Copernican doctrine, which is the order described in the notary memorandum; the illegitimacy and likely non-occurrence of this order are also supported by the evolution of the 1633 proceedings, since Galileo denied having received it and the prosecution dropped the related charge in light of Bellarmine’s certificate. Then there was Bellarmine’s warning not to hold or defend Copernicanism as true, or as compatible with Scripture, but only as a hypothesis; this order was obviously issued, admitted as received by Galileo, and eventually confessed as unintentionally violated by him. However, before the 1633 sentence, there was no distinct order not to hold or defend Copernicanism as probable, so this may be regarded as the addition or invention of a new prohibition. Or, more charitably, perhaps this formulation in the sentence is essentially interpreting the term “true” in Bellarmine’s warning to include “probably true.” But to be charitable to Galileo, we could say that he too is sticking to Bellarmine’s warning, but interpreting the term “hypothesis” to include “probable, although not yet demonstrated, truth.”

In the text of the sentence, the verdict was followed by a list of penalties. The first was that Galileo was to immediately recite an “abjuration” of the “above mentioned errors and heresies.” Second, the Dialogue was to be banned by a public edict. Third, Galileo would be kept under imprisonment indefinitely. And fourth, he would have to recite the seven penitential psalms once a week for three years. Finally, the Inquisition declared that it reserved the right to reduce or abrogate any or all of these penalties.

We will see presently what the abjuration amounted to. But note that, although it was a penalty in the sense that it was a great humiliation for anyone to have to recant one’s views, it was also a procedural step for the culprit to gain absolution of the sin of heresy.

The book’s prohibition took effect immediately, although a year passed before it would be included in a formal decree of the Congregation of the Index that listed other books as well. The recitation of the penitential psalms was a “spiritual” penance for the good of Galileo’s soul.

The “imprisonment” stipulated in the sentence never did involve detention in a real prison, although it did last for the rest of his life. For two more days, Galileo was confined to the prosecutor’s apartment at the Inquisition palace, which had been his place of detention for certain periods of the trial, April 12–30 and June 21–2. For about a week, June 24 to July 1, Galileo was under house arrest at Villa Medici, the sumptuous palace in Rome belonging to the Tuscan grand dukes. Then his place of detention was commuted to the residence of the archbishop of Siena, who was a good friend of Galileo’s; he stayed there from early July to early December. Finally, from December 17, 1633 onward, Galileo was under house arrest at his own villa in Arcetri near Florence.

However, these details, which are available to us today, were generally unknown until the relevant documents were discovered and published at the end of the eighteenth century. So, for about 150 years, on the basis of the sentence one could justifiably conclude that Galileo had been put in prison as a result of his condemnation. This led to the growth of the prison myth,10 which eventually acquired a life of its own.

The sentence ended with the signatures of seven out of the ten cardinal-inquisitors. This fact would hardly need comment were it not that three signatures are thus missing—those of Francesco Barberini, Gasparo Borgia, and Laudivio Zacchia. Francesco Barberini was the pope’s nephew and the Vatican secretary of state; he was the most powerful man in Rome after the pope himself. Borgia was the Spanish ambassador and leader of the Spanish party in Rome; a year earlier, he had threatened the pope with impeachment on account of his behavior in the Thirty Years’ War. Zacchia was the chief of staff of the papal household. Given the powerful positions of these three cardinals, the explanation of the missing signatures has become one of the many controversial questions in the Galileo affair. Two obvious possibilities are that the lack of these signatures reflected a significant disagreement among the ten judges, or merely that some of them were not present at the meeting when the document was signed.

Abjuration

The most immediate penalty for Galileo’s crime and the final procedural step in the trial was for Galileo to recite an “abjuration.”11 Its content and wording were relatively standardized and provided to him by the Inquisition’s officials.

The document begins with a multifaceted confession. Galileo admitted having been notified that the heliocentric, geokinetic doctrine was contrary to Scripture and so could not be held or defended, and having subsequently published a book that held and defended this doctrine. These two admissions corresponded to what had actually happened during the proceedings and to what the sentence had reported.

However, Galileo also admitted to having been served with the full special injunction, i.e., with the judicial precept to completely abandon the doctrine and not to hold, defend, or teach it in any way whatever, orally or in writing. This admission went beyond his previous confession and beyond the sentence, which had allowed that Bellarmine’s certificate cast doubt on the special injunction having been served. So the text of the abjuration made Galileo confess additionally to violating the special injunction besides unintentionally violating Bellarmine’s warning.

Galileo then acknowledged that because of these transgressions, he had been judged to be vehemently suspected of heresy, and that this verdict was right when he spoke of “this vehement suspicion, rightly conceived against me.”12 He was confessing that he was guilty as judged.

After these confessions, we come to the abjuration proper, where the culprit “with a sincere heart and unfeigned faith”13 abjured and cursed the above-mentioned errors and heresies. This has led to the question whether such Galilean abjuring amounted to perjury—another classic controversy of the Galileo affair.

The culprit then made a series of solemn promises about future thought and behavior: that he would never again hold any such beliefs; that he would denounce to Church officials any heretics or suspected heretics; that he would comply with the penalties imposed on him by the judges; and that he would submit to further penalties if he failed to comply with the current ones. Such promises suggest something which was entirely normal for Inquisitorial practice: that at the final session of the trial Galileo read this document word for word and affixed his own handwritten signature to it at the end, but that the text had been compiled by the Inquisition’s clerks.

Whether this abjuration was extorted from Galileo during the “rigorous examination,” perhaps in exchange for doing without additional “rigors,” as some scholars have claimed,14 is a controversial question that we can leave here simply as an issue to be added to our accumulating stock. But it ought to be clear by now and it certainly is striking that in this abjuration Galileo was not only being made to retract earlier beliefs, attitudes, and behavior, but also being made to plead guilty to the verdict already announced by the judges and to confess to a transgression not confessed earlier.

Thus, the original Galileo affair ended and a new one began. What ended was the Inquisition’s trial of Galileo, which started in 1613 with his letter to Castelli, refuting the biblical objection to the geokinetic hypothesis, and which climaxed in 1633 with his condemnation as a suspected heretic, for writing a book that defended this hypothesis and rejected the astronomical authority of Scripture. What began was the unresolved and perhaps unresolvable controversy about the facts, the issues, the causes, and the lessons of the original episode. This is a cause célèbre which continues to our own day and whose fascination rivals that of the original one.