9

Prescription for Success

Banishing Addictions to Stimulants, Sedatives, and Opioids

In a world of stress, anxiety, insomnia, family pressures, red-eye flights, ten-hour workdays, three-hour traffic jams—heck, world hunger and global warming!—it’s no surprise that so many of us find ourselves in need of stimulants and tranquilizers, whether prescription or something not considered legal. So we drink coffee, tea, espresso, and caffeinated sodas, and we have our afternoon martinis and late-night whiskeys. These “uppers” and “downers” are not without fault—as you can read in chapters 4 and 8, caffeine and alcohol deplete the body of nutrients and have their own set of dependency issues. But some of us also use synthetic stimulants and tranquilizers. Perhaps they were prescribed to us by a physician to treat insomnia or to help us through an emotionally difficult time. Perhaps they belong to a friend or loved one who hopes to help us by sharing his or her prescription. But make no mistake about it—they are legal, yes, and they are often prescribed by a physician, but if prescription stimulants or sedatives are used for an extended period of time or are taken in large doses, they can cause an addiction so severe that it has been likened to heroin dependency. It is also possible that a “helpful” friend thinks an illegal substance like cocaine or crystal meth might be the answer to getting through a challenging time, or just something you might at first find “fun.”

It’s no secret that stimulants, sedatives, and opioid painkillers are addictive and dangerous. Just read the label on the bottle. What’s worrisome is that they’re some of the most commonly prescribed drugs in the world—and among the most often abused.

AMPHETAMINES

Amphetamines were first synthesized in 1887, although their stimulant properties were not recognized until 1927. They were originally used in the treatment of asthma. Later, amphetamines were used to treat narcolepsy, to treat hyperactivity in children, to counteract the effects of depressants, and (to a lesser degree) to aid weight loss and relieve fatigue and depression. During World War II American, British, German, Italian, and Japanese soldiers were given hundreds of millions of doses of amphetamines—even though fatal intoxications occurred often—in lieu of rations and to help the soldiers overcome depression and low spirits.

The Amphetamine Family

Amphetamine

Dextroamphetamine

Methamphetamine

Biphetamine

Methylphenidate

Amphetamines are central nervous system stimulants. They create a feeling of euphoria and offer the body more energy, alertness, and ability to concentrate. They are twenty times more intense than cocaine—but they’re legal.

As stimulants, amphetamines have a variety of uses. They’re often taken by those who need to stay awake and alert for extended periods of time, such as long-distance drivers and soldiers on active duty. Students often use amphetamines not only to help them stay awake for long nights of studying but also to help them concentrate. Amphetamines suppress appetite, so they’re often prescribed to dieters. And they’re even used in various forms to treat hyperactivity—although it may seem odd to give a stimulant to treat hyperactivity, it works. Many researchers are involved in studying this paradox.

However, amphetamines have many serious side effects, and they can be addictive. There’s no question that amphetamines are physically addictive; any physician who prescribes them to you will warn you of this danger. But amphetamines also create a self-perpetuating cycle of psychological addiction. When the amphetamine buzz wears off, depression and lethargy set in. The answer? More amphetamines. And amphetamines used for an extended period of time—overextending the capacities of mind and body—can cause inertia, loss of perception, and mental dullness. The answer? Sadly, it’s too often more amphetamines.

Side effects of amphetamines include increased heart rate, elevated blood pressure, heart palpitations, sweating, dry mouth, headache, insomnia, diarrhea, tremors, hallucinations, sleeplessness, confusion, restlessness, and a general feeling of apprehension and anxiety. Chronic amphetamine users suffer from sore throats, headaches, eye deterioration, and fatigue. They can become irritable and unstable and are likely candidates for nervous breakdowns.

As you might assume, amphetamines taken during pregnancy pose high risk to the infant. Pregnant women should never take amphetamines except under the strict supervision of their physician.

Tolerance to amphetamines develops rapidly, requiring that the user take larger and larger dosages to feel the effects. However, large amounts of amphetamines can elevate blood pressure enough to blow out blood vessels to the brain and cause a stroke. Overdose can cause convulsions, coma, and even death.

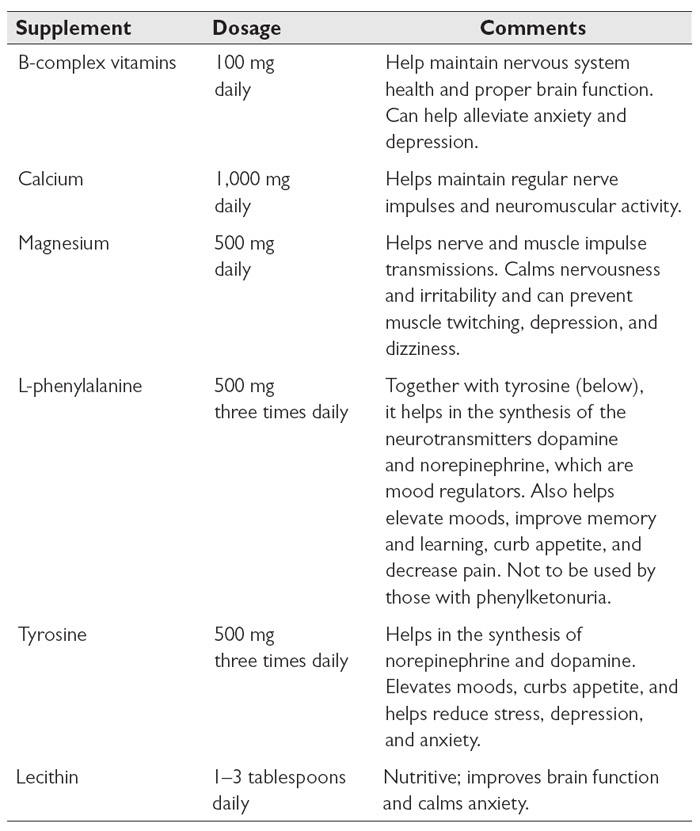

Supplement Therapy

Here are some supplements that can aid in withdrawal from amphetamines:

Herbal Therapy

A number of herbs can help you kick an amphetamine addiction. Some help rebuild a body that has been worn down through long-term stimulant use. Others are natural stimulants that can be used as temporary substitutes for their chemical counterparts.

- Aniseed stabilizes blood sugar levels and is a natural energy builder.

- Asparagus root calms emotional irritability. It’s highly nutritive and can help rebuild kidneys injured from long-term stimulant use.

- Atractylodes increases energy and builds chi.

- Cola nut is a natural stimulant. It does contain caffeine, though, which has its own drawbacks.

- Dandelion root helps remove drug residue from the body by improving liver function.

- Ephedra is a natural stimulant and can be used as a temporary substitute for chemical stimulants. See the cautions in chapter 2 before using ephedra.

- Fennel seed stabilizes blood sugar levels, decreases the desire for stimulants, and is mildly energizing.

- Ginkgo improves cerebral blood flow and lifts depression.

- Ginseng helps repair adrenal glands harmed from stimulant use and nourishes a frazzled nervous system.

- Gotu kola is a nerve and brain restorative. It can help you feel mentally alert without stimulants.

- Green tea is another natural stimulant. Like cola nut, though, green tea contains caffeine.

- Ho shou wu is a nerve restorative. It calms anxiety and gently builds energy.

- Hyssop calms hysteria and cleanses drug residue from the body.

- Jujube nourishes the adrenal glands, calms anxiety and depression, and is gently energizing.

- Lemon balm helps calm the spirit and makes withdrawal easier. It’s also a mild antidepressant.

- Licorice root stabilizes blood sugar levels and functions as an adrenal and chi tonic.

- Marsh mallow root helps soothe and rebuild a dry, deficient constitution, such as one burned out from chemical stimulants.

- Milk thistle seed helps rebuild a liver damaged by drug abuse.

- Oat seed or oatstraw nourishes the nerves and diminishes the desire for drugs.

- Peppermint is a mild stimulant that also promotes relaxation.

- Reishi calms the nerves, reduces anxiety, and helps repair damage from long-term stimulant use.

- Schizandra berry improves physical endurance, calms anxiety, and is a nerve restorative.

- Valerian can help your body rest and recover from overstimulation.

- Yerba maté is a gentle stimulant that is also rich in antioxidants and can relieve depression.

Aromatherapy

Essential oils to smell to deter cravings for amphetamines and other stimulants include bergamot, clove, geranium, grapefruit, lemon, lime, and orange. These essential oils relieve stress and fatigue, uplift the spirits, and act as gentle stimulants.

Energy the Natural Way

Read the section “Overcoming Fatigue and Increasing Energy” (see here) for ideas on healthy ways to get going.

COCAINE

Like amphetamines, cocaine is a stimulant—a very strong one. It’s extracted from the leaves of the coca plant (Erythroxylum coca), a shrub native to the mountains of Peru. The leaves look similar to bay leaves, and indigenous peoples have been growing and harvesting them for at least four thousand years. The Inca considered coca to be a gift from the gods and reserved its use for high priests, royalty, and other important personages. They used it as a tonic and stimulant. It stimulates digestion and helps the body utilize oxygen better; in fact, it is an excellent remedy for altitude sickness. In ancient times, when the Inca would communicate across their vast kingdom by a system of messengers, those long-distance runners would chew coca leaf to boost their endurance.

Coca leaves are actually a good source of nutrition. They are about 19 percent protein and 44 percent carbohydrates, and they also contain beta-carotene, vitamin B2, calcium, and phosphorus. They also have many medicinal uses.

Coca is an herb, however, and cocaine is a dangerous drug. It was first isolated from the coca leaf by European scientists in the 1850s. Ophthalmologist Carl Koller (a colleague of Freud’s) is credited with popularizing the new drug; he used it as an anesthetic for cataract surgery. In 1886, American pharmacist John Pemberton founded Coca-Cola, and its signature product was a sugary, bubbly drink laced with cocaine. Though Coca-Cola removed cocaine from its products in 1903, the lid was off the genie’s bottle. Cocaine was declared illegal in 1920, but by the 1980s, the illicit cocaine trade was thriving, crack cocaine had entered the scene, and America’s War on Drugs was under way—and failing. As the drug’s history has borne out, cocaine is extremely addictive.

In the brain, cocaine blocks the reuptake, or recycling, of dopamine, as well as norepinephrine and serotonin. Dopamine, as we learned in chapter 1, is a neurotransmitter and hormone that stimulates the pleasure or reward centers in the brain. It lifts both energy and spirits; in fact, it’s called the “feel good” hormone. When cocaine blocks its reuptake, dopamine builds up in the brain and its effects are amplified. Users feel a tremendous surge of energy, confidence, and alertness. But that euphoric response is short-lived.

While it may feel like cocaine produces energy, it actually removes energy from the body. It puts tremendous stress on all of the systems and organs, especially the heart, liver, spleen, and pancreas. It exhausts the adrenal glands. It radically boosts heart rate and blood pressure while at the same time constricting blood vessels; in fact, chronic cocaine users have a risk of heart attack and stroke. And when the cocaine “high” is gone, dopamine levels plummet, and users feel the need to take more cocaine to feel normal.

Eastern Perspectives on Cocaine

In Asian medicine, cocaine use is said to cause heat and dampness. Like other addictive substances, it depletes the jing, or essence, of the kidneys.

For anyone trying to quit a cocaine habit, the first two weeks are the most challenging. You may need to deal with depression, anxiety, and lethargy. Avoid temptation and stay away from anyone else who is using cocaine. Stay busy. Exercise—it stimulates the body’s own production of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin.

Nutritional Therapy

Nutritional support is imperative to the person giving up cocaine. Fish, being high in brain-supporting amino acids, is a good food to eat, as are complex carbohydrates such as oatmeal and popcorn, which can calm an agitated nervous system. Fava beans, in particular, contain high levels of dihydroxyphenylalanine, a precursor to dopamine that could potentially boost dopamine levels in the brain. Pumpkin seeds build chi, which can help addicts leave the habit behind. Eat lots of foods that are rich in selenium—Brazil nuts, sunflower seeds, cabbage, broccoli, nutritional yeast, and fish can help improve mood.

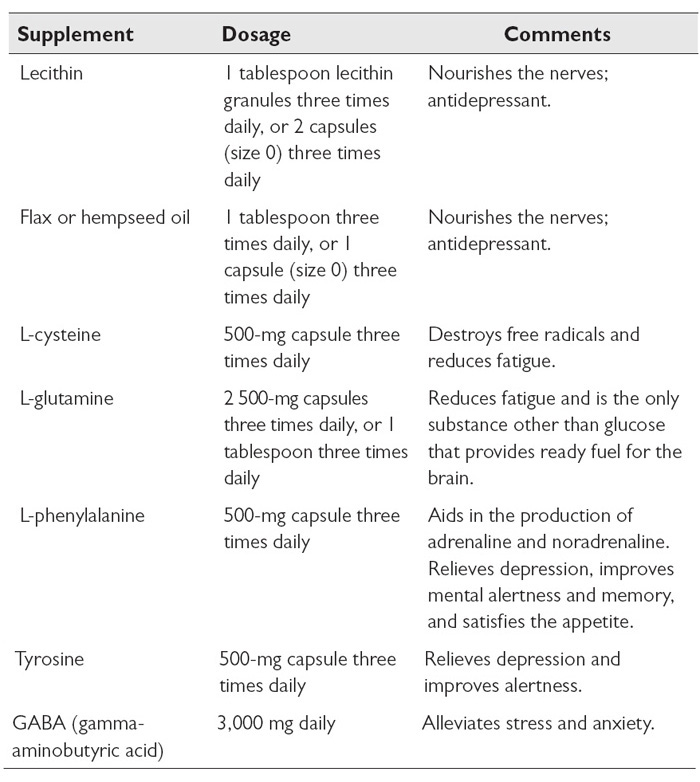

Supplement Therapy

Rather than paying the exorbitant cost of cocaine, a much better solution is to invest in supplements that can help nourish the body and reduce cravings.

Herbal Therapy

Herbs can be allies in overcoming a dependence on cocaine and other stimulant drugs. Some herbs help to detoxify the body of drug residues, making it easier to give up the habit. Some may be stimulating, yet also provide nourishment, tonifying the adrenals rather than depleting them and other body systems.

- Chaparral can help cleanse drug residues from the body.

- Ephedra mimics some of the effects of cocaine by stimulating the nervous system and the production of adrenaline, which can be helpful during the transition period. However, like cocaine, it can cause anxiety, insomnia, and elevated blood pressure and should only be used for short periods of time.

- Gotu kola and ginkgo can help you get your head thinking straight again by improving nerve transmission and mental clarity.

- Passionflower and skullcap are calming and cooling.

- Slippery elm bark or marsh mallow root can repair the delicate tissues of the nasal passages if they’ve been damaged by snorting cocaine.

- Valerian can help during the first few days of withdrawal as it is calming.

Note: If you are using any sedative herbs, like valerian, and also the stimulant ephedra, be sure to separate their doses by at least four hours so that they do not cancel each other’s effects.

SEDATIVES

Sedating agents can be broken down into two categories: barbiturates and everything else. The term tranquilizer is often used to describe any tranquilizing agent that is not a barbiturate. For the sake of clarity, I will use sedative to describe all tranquilizing agents, including barbiturates, and tranquilizer to describe specifically nonbarbiturate sedating agents.

Sedatives are central nervous system depressants. They’re often prescribed to reduce mental or physical tension, relieve anxiety, create a sense of well-being, relax the muscles, and cause drowsiness. In small doses they generally have a calming and relaxing effect on the central nervous system; in larger doses they induce sleep. When used over extended periods of time, however, they become highly addictive and can cause lethargy, irritability, nightmares, nausea, headache, skin rashes, impotence, and tremors.

The Name Game

- Barbiturates include amobarbital, aprobarbital, barbital, butabarbital, mephobarbital, methaqualone, methohexital, pentobarbital, phenobarbital, secobarbital, thiamylal, and thiopental.

- Tranquilizers are too numerous to list, but among them are chloral hydrate, chlordiazepoxide, ethclorvynol, flurazepam, glutethimide, hydroxyzines, lithium preparations, meprobamate combinations, methyprylon, molindone hydrochloride, nitrazepam, and thioxanthene.

- Benzodiazepines are a major class of nonbarbiturate tranquilizers. They include alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, diazepam, estazolam, flurazepam, halazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, oxazepam, prazepam, quazepam, temazepam, and triazolam.

Using sedatives can slow your normal reactions, dull your feelings, and cause depression, appetite loss, dizziness, lethargy, speech problems, allergic reactions, digestive distress, constipation, diarrhea, headaches, menstrual and sexual disorders, sinus pain, joint pain, blurry vision, memory loss, and suicidal tendencies. As with alcohol, driving while under the influence of a sedative is dangerous. Sedatives impair both judgment and fine motor skills. If you’re taking sedatives, under no circumstances should you be driving!

Never drink alcohol while you are taking sedatives. Alcohol multiplies a sedative’s effect and can lead to accidental overdose—that is, coma or death. In addition, do not take sedatives if you are pregnant.

Barbiturates

Barbiturates are synthetic sedatives derived from barbituric acid. Barbiturates were first introduced in 1846 and were widely marketed from 1912 until about 1960, when nonbarbiturate sedatives replaced them. They’re often prescribed to people with insomnia or excessive anxiety. However, they also have an effect that can be likened to an alcohol high—loss of inhibition, boisterous or aggressive behavior, loss of muscle coordination, and sedation—and so they have become common drugs of abuse.

Barbiturates are extremely addictive; their physical and psychological habituation is considered as serious as that of heroin. They cause many accidental overdoses because a toxic dose of barbiturates is often only a little more than what’s needed to produce the intoxicating effect. Following chronic high dosages, withdrawal symptoms can be extremely serious, even life threatening. They include insomnia, anxiety, tremors, convulsions, delirium, shock, and, in cases of abrupt withdrawal, coma and death.

Impairment of judgment and fine motor skills will long outlast the sedative effects of a dose of barbiturates. You may feel that the dose has worn off before the effects have truly dissipated.

Tranquilizers

Nonbarbiturate and benzodiazepine tranquilizers are generally safer than barbiturates, and consequently they are now the preferred drug for treatment of insomnia and anxiety. As the number of these sedatives available has risen, so, too, has the frequency of abuse and addiction. According to the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, in that year 14.7 percent of the U.S. population used some form of tranquilizer, and 2.3 percent misused some form of tranquilizer.

Tranquilizers are less potent sleep inducers than barbiturates are, and they’re less likely to interfere with motor skills. When they were first marketed in the 1950s and 1960s, most people believed they were nonaddictive and perfectly safe to use. Research has since disproved this innocent theory.

Tranquilizers were originally used to treat psychoses (including schizophrenia), to calm violence and hyperactivity, and to make patients more receptive to therapy. Nowadays they’re most often used to treat insomnia and stress. They’re intended to be used for short periods only (from one to six weeks) to help people through difficult times, such as divorce or the death of a loved one. Most people can give them up without problems after these short periods of usage, though some users encounter withdrawal reactions.

When tranquilizers are used for extended periods of time, they begin to lose their beneficial effects, and they become more difficult to give up. Users will develop a tolerance and must take more to produce any effect, leading to an accelerated rate of dependency and possible overdose.

If you have used tranquilizers, including benzodiazepines, for more than four weeks straight, withdraw gradually rather than quitting cold turkey, and consult with your physician for advice first. Abrupt withdrawal can cause nausea, cramps, delirium, convulsions, and in rare cases sudden death.

Benzodiazepine tranquilizers are the most commonly prescribed of nonbarbiturate sedatives. They’re generally safe for short-term use (though they become potentially lethal when combined with alcohol); still, when used for extended periods of time they can become addictive. Benzodiazepines slow heartbeat and respiratory rate, lower blood pressure, and have a mildly depressing action on the nervous system. They often cause loss of coordination and dizziness. They can also induce sleep, though they decrease the amount of REM dream time and inhibit the emotional clearing that is a vital function of dreaming and sleeping. When benzodiazepines are discontinued, they can have a rebound effect marked by vivid and excessive dreams.

Behavior Therapy

Because sedatives have an effect similar to that of alcohol, follow the guidelines for alcohol addiction outlined in chapter 8. Sudden withdrawal from sedatives is very dangerous; it traumatizes the liver and heart and can cause seizures, coma, or even death. Daily doses are best decreased gradually—by 10 to 25 percent every week or month, depending on how large your average dose is. The longer you’ve been taking sedatives, the slower the letting-go process should be.

If you’re using sedatives originally prescribed by a physician, consult with him or her about decreasing their use. Anyone suffering from a strong addiction to barbiturates or tranquilizers should undergo the withdrawal process in a clinically supervised setting.

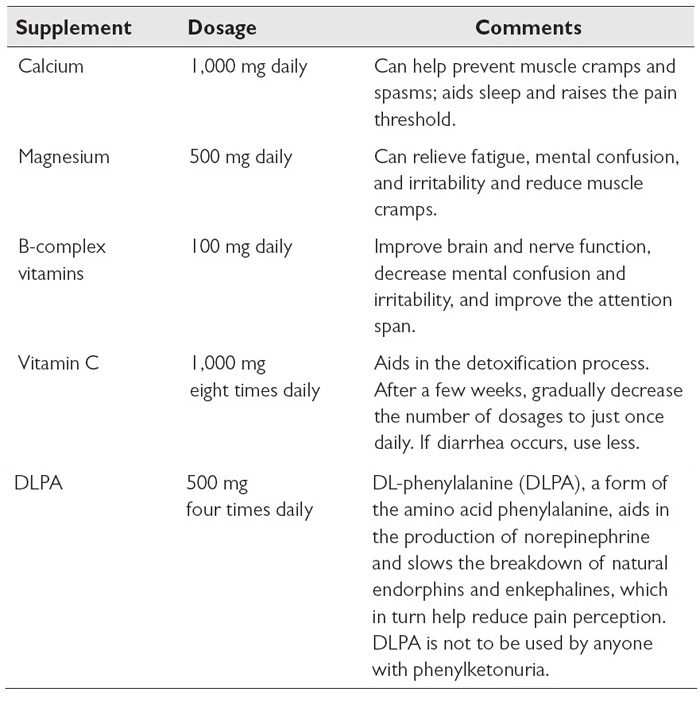

Supplement Therapy

The following supplements can aid in withdrawal from sedatives:

In The Official Nutrition Education Association Home Study Course in the New Nutrition, author Ruth Long tells us about a pilot study conducted by Alfred Libby and Irwin Stone to examine the use of vitamin C in giving up addictions. Drug addicts were given sodium ascorbate, a form of vitamin C that’s easy on the digestive tract. The greater the amount of drugs they’d used, the higher the dose of vitamin C they received. The researchers found that the vitamin seemed to minimize withdrawal symptoms. After a few days the addicts reported restored appetite, restful sleep, and a genuine sense of feeling good.

Herbal Therapy

There are many herbs that can benefit someone struggling to give up an addiction to prescription sedatives.

- Ashwagandha helps rebuild a nervous system depleted by drug use. It calms anxiety, stress, and tremors and reduces mental fatigue.

- Atractylodes increases energy, builds chi, and helps restore a liver damaged by drug abuse.

- Blue vervain is a mild sedative; it relieves insomnia and calms anxiety.

- Bupleurum is a mild muscle relaxant. It helps mellow anger and relieve depression, stress, and pain.

- Calamus calms hysteria, relieves depression, and enhances perception. It helps restore brain function that has been impaired by drug abuse.

- California poppy is a safe, natural sedative that calms restlessness and anxiety.

- Catnip is a mild sedative that calms anxiety and restlessness.

- Chamomile relieves anxiety, insomnia, pain, and stress and can decrease nightmare episodes.

- Codonopsis helps relieve insomnia and stress while also improving energy levels.

- Corydalis is an effective pain-relieving agent that is nonaddictive.

- Cyperus is a natural sedative. It’s especially helpful during the withdrawal period.

- Ginseng nourishes the nerves and adrenal glands. It helps relieve stress and improves physical and mental energy.

- Gotu kola is a nerve and brain restorative that also improves depression.

- Hops are a natural sedative that relieve anxiety, stress, and insomnia. Hops can also calm delirium and tremors that may occur during withdrawal.

- Jujube calms the spirit and can replenish depleted adrenal glands and nerves.

- Kava kava calms fear, pain, and anxiety. It’s mildly euphoric and can encourage deep, restful sleep.

- Lavender flowers ease the withdrawal from sedatives. Lavender is itself a natural sedative and can calm and lift the spirits.

- Lemon balm also eases the withdrawal from sedatives. It’s mildly mood elevating yet also calming.

- Licorice root helps stabilize blood sugar levels, relieves stress and fatigue, and promotes calmness.

- Linden leaf and flower calm the spirits and reduce stress and anxiety.

- Milk thistle seed improves the breakdown and release of drug residues stored in the liver.

- Motherwort calms anxiety and hysteria; it functions as both a sedative and a rejuvenative.

- Mugwort can be ingested in small amounts to help the body detoxify, it can also be burned as an incense. It calms hysteria and lifts depression.

- Oat seed or oatstraw decreases anxiety and calms and strengthens the nerves. Both help decrease the desire for sedatives.

- Passionflower helps relieve stress and insomnia. During the withdrawal period it can calm and comfort the spirit.

- Reishi relieves stress, anxiety, and insomnia by calming the nerves.

- Sage clears drug residues from the body and restores the nerves.

- St. John’s wort helps lift the depression and anxiety that may be the root cause of addictive tendencies.

- Schizandra berry calms anxiety, relieves irritability, and is a nerve restorative.

- Skullcap calms anxiety and relaxes tremors during withdrawal.

- Valerian can be used as a nonaddictive alternative for sedatives. It aids sleep and relaxes the muscles.

- Wood betony relieves anxiety and is a nerve restorative.

Aromatherapy

Inhalations of the following essential oils can be very effective in helping someone overcome an addiction to sedatives:

- Chamomile relieves tension, quiets anger and oversensitivity, and aids sleep.

- Geranium lifts depression, relieves stress, and makes you feel more mentally alert.

- Jasmine helps relieve fear, pessimism, and depression and boosts self-confidence.

- Lavender is cleansing and emotionally balancing. It helps relieve stress and insomnia, soothes anger, and lifts depression.

- Marjoram dispels grief, anxiety, irritability, and insomnia.

- Neroli is a natural antidepressant. It’s calming and relaxing and helps relieve anxiety, fear, hopelessness, and depression.

- Rose helps you feel more loving and patient. It relieves grief and depression.

Natural Ways to Conquer Stress, Insomnia, and Anxiety

Addiction to sedatives is often a consequence of stress, insomnia, and anxiety. For information on natural methods for dealing with stressors, turn to chapter 12.

OPIOIDS

Opiates are drugs that include or are derived from opium. Opioids are “opiate-like” drugs—that is, drugs that have the same effect as opiates, though not necessarily the same chemical structure. All opiates are opioids, but not all opioids are opiates. Opioids include heroin, fentanyl, oxycodone, hydrocodone, methadone, codeine, morphine, and others.

Opium itself is harvested from the unripe seedpods of the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum), and it has long been valued for its medicinal and psychoactive qualities. It is perhaps most valued for its use as a natural painkiller, and it is that trait—studied, extracted, isolated, concentrated, and amplified over centuries’ worth of human civilization—that eventually led to the creation of opioid drugs and the current epidemic of opioid abuse.

The human body makes its own opioids as part of its control mechanisms for the pain response and the mesolimbic reward system. These endogenous opioids, as they’re known, include endorphins and enkephalin, and among other things, they calm anxiety, boost mood, and mediate our response to pain. When exogenous opioids—that is, opioid drugs, like heroin or morphine—bind to opioid receptors in the brain, they block pain signals and trigger the release of large amounts of dopamine.

Opioids as a Cure for Opioid Addiction: A Circular History

Opium’s addictive qualities have been well known throughout its history of use. Morphine, an alkaloid, was first isolated from opium in 1805, and it was soon thereafter advertised as a cure for opium addiction. The rationale was that you needed a lot less morphine to get the same effects as you would get from opium. But, as it turns out, morphine is also highly addictive.

Heroin was first synthesized from morphine in 1874. It was intended to serve as a less addictive alternative to morphine and was actually used to treat morphine and opium addiction, but of course we all know how that turned out. Apparently, the more a substance is refined, the more problems it causes.

Today, we see methadone advertised as a primary intervention in the treatment of opioid addiction. Methadone does block the effects of heroin and thereby decreases the desire to use it. But methadone itself is an opioid. Though it does not provide the euphoric experience, it is addictive—just as addictive as heroin, some people claim. Are we again trying to cure one addiction by substituting another? Are we digging an even deeper hole in the opioid swamp?

As is the case with cocaine, a f lood of dopamine in the brain produces a “high”—a thrilling feeling of euphoria. However, once the effect has passed, dopamine levels drop, and users will need to take more opioids just to feel normal. In other words, over time, using opioids reinforces the desire to take more opioids. And that’s addiction.

Opioids certainly have their place in medicine. They are very good at blocking pain. But they should only be used when absolutely necessary, and only under the careful watch of a health-care professional, and only for a short period of time. For people with chronic pain, other solutions must be found. (For some natural solutions to pain, see here.)

Behavioral Therapy

Hard physical labor, such as gardening, can be very therapeutic. Sweating therapy—for instance in an infrared sauna—which can help clear the body of drug residues, is also suggested. Also consider kundalini yoga as a natural way to invigorate brain chemistry. Yoga, qigong, and tai chi are other methods that help calm and invigorate the mind and body.

Nutritional Therapy

For general nutritional guidelines to aid in overcoming opioid addiction, refer to pages 27–30 in chapter 2.

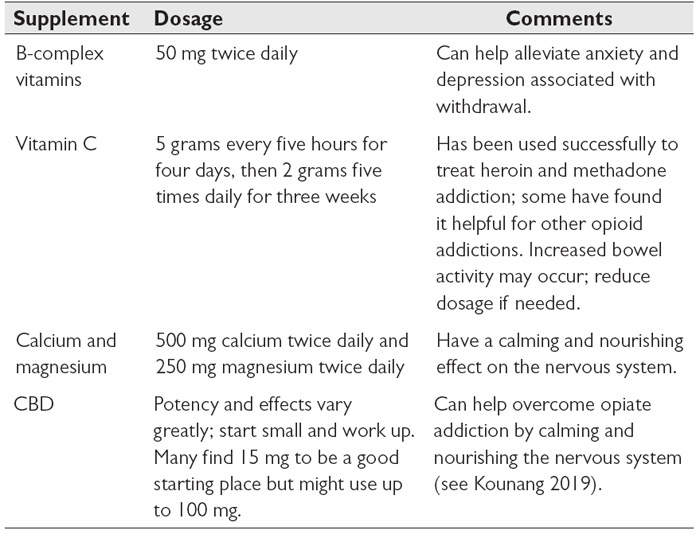

Supplement Therapy

The supplements in the table below can aid in withdrawal from opioids.

Herbal Therapy

Herbs can be helpful in detoxifying and nourishing the body as well as calming the nervous system of the person giving up an opioid addiction.

- Chaparral capsules, up to twenty a day, can help opioid addicts detox.

- Ginger is used to reduce nausea, inflammation, and pain associated with opioid withdrawal.

- Iboga reduces cravings for opiates and often helps bypass the discomfort of withdrawal. Deep spiritual insight as to some of the causes of one’s addiction are also possible during a potent entheogenic experience.

- Kava kava relaxes the muscles without blocking nerve signals.

- Licorice root can stabilize blood sugar levels.

- Mullein encourages improved respiration, which has a calming effect on the nervous system.

- Passionflower slows down the breakdown of neurotransmitters.

- Spearmint calms the stomach and nervous system.

- Oatstraw is used in India to treat opioid addiction by calming and nourishing the nervous system.

- Valerian helps addicts who need calming during the early stages of withdrawal.

For stomach pain from opioid withdrawal, give a tea of cinnamon and licorice.

Withdrawal from opioids is unlikely to be fatal, though people who have been through it describe it as going through a “super flu” involving the respiratory system.