Gerard Klein

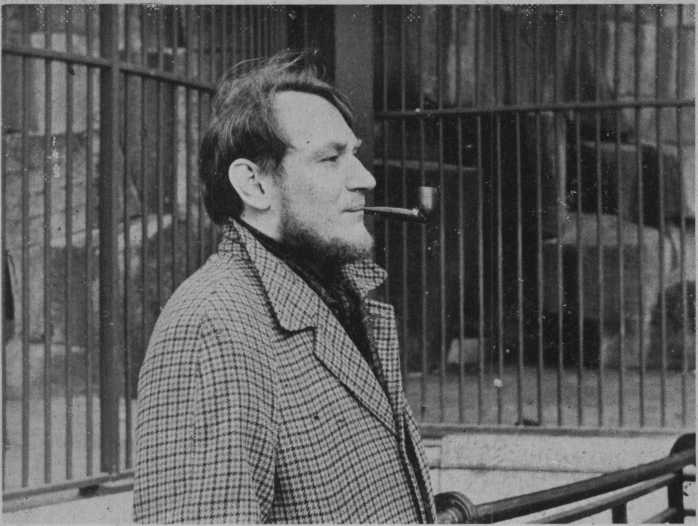

John Brunner

translated by John Brunner

DOUBLEDAY & COMPANY, INC. GARDEN CITY, NEW YORK

First published in France as Les Seigneurs de la Guerre Copyright © 1971 Editions Robert Laffont, S.A. Translation copyright © 1973 by Doubleday & Company, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America

The Overlords

Le del charrie un mauvais grain.

Est-ce aujourd'hui, est-ce demain Que tous les peuples harasses Vivront enfin pour s’embrasser?

Et rataplan et rataplan

Les morts se vengent des vivants.

The welkin bears a seed of sorrow—

Is it today, is it tomorrow That all the weary peoples will Learn how to kiss instead of kill?

Rat-tat-tat goes the drummer’s stick— The dead take vengeance on the quick.

Song by Frehel

The Monster was weeping like a little child—not with remorse at having killed three dozen men, but at finding itself so far from its mother world. Corson could understand its distress; it was all he could do not to give way to the same feeling.

In the darkness his hands groped along the ground, warily because according to the Briefings there were plants here which cut like razors. They encountered a clear space. Only then, and with extreme slowness, did he advance a little. Beyond, the “grass” was as soft as a fur pelt. Surprised, Corson drew back his hands. The plants ought to be hard and knife-keen. Uria was a hostile and dangerous world. According to the Briefings, soft plants ought to indicate a trap. Uria was at war with Earth.

What he needed to know most urgently was whether the natives were already aware of the arrival of two strangers—the Monster and George Corson. The Monster was equipped to cope with them. Corson wasn't. For the twentieth time he worked it out: the natives would have seen the ship founder in flames and would probably assume its crew to be dead. They wouldn’t carry out a search during the night if the Urian jungle were even half as dangerous as the Briefings claimed.

His calculations always brought Corson to the same conclusion.

He had to face three mortal threats: from the Monster, from the natives, and from the wild beasts of Uria. Weighing the risks, he decided to stand up. He wouldn’t get far on all fours. If he found himself too close to the Monster, that would cost him his life. He could estimate what direction it lay in, but not how. far away it was. The night seemed to muffle sound, or perhaps fear had taken the edge off his hearing.

Gently, gently, he rose to his feet, trying not to rustle the grass or any foliage there might be. Stars shone peacefully overhead, in patterns that were strange but not menacing, stars like those he had seen scores of times from the surface of worlds scattered around the galaxy. The starry vault was a reassuring sight, if a meaningless one. Long ago, on Earth, men had coined names for constellations which they believed unchangeable, but which were only the result of observing the heavens from a briefly privileged vantage point That was past; so too was the divine ranking of the stars.

The situation, Corson told himself, was by no means hopeless. He had a good gun, although it was almost empty. He had eaten and drunk just before the accident, which would enable him to keep going for some hours. The air was fresh, which would prevent him from becoming drowsy. On top of that he was the sole survivor of a crew of thirty-seven men and hence must enjoy incredible good luck. Last, he could move freely; he was neither handicapped nor even hurt.

The wails of the Monster redoubled, which brought Corson’s attention back to the most pressing of his problems. If he hadn’t been very close to the Monster’s cage when it launched its attack, he would probably now be drifting in a thin cloud through the Urian stratosphere. He had been trying to communicate with the Monster, as his job required. From the other side of an invisible wall the Monster fixed him with six of the eighteen eyes ringing what it was convenient to call its waist. Those lidless orbs changed color in a variable rhythm which constituted one of its modes of communication. The six long claw-tipped fingers on each of its six paws tap-tapped on the floor of its cage, in a second communication mode, and a dull monotonous cry escaped from its upper orifice, which Corson could not see. The Monster was at least three times his height, and its mouth was surrounded by a forest of tendrils which from a distance might be mistaken for hairs, but close up looked pretty much like what they were: slender strands as tough as steel, capable both of lashing out at fearful speed and of acting as tactile antennae.

Corson had never doubted that the Monster was intelligent. Besides, the Briefings said so. It might even be more intelligent than a man. The great weakness of the species it belonged to had been to Overlook—perhaps to scorn—that great invention which had made humans and sundry other races so powerful: society. The Briefings declared that this case was not unique. On Earth itself, before the age of space and the systematic exploitation of the oceans, there had existed in the sea an intelligent species, remarkably individualistic, which had never taken the trouble to build a civilization. Extinction had been the price the dolphins paid for their neglect. But creating a society was not in itself a warranty that a species would survive. The pitiless war between Earth and Uria was in a fair way to proving that.

The eyes, the fingers, and the voice of the Monster, from the far side of the invisible wall, conveyed a message which Corson understood perfectly well even though he was unable to decipher the creature’s language: “As soon as I can, I shall destroy you!”

For a reason unknown to him, the chance had arisen. He couldn’t believe that the ship’s generators had broken down. More likely, Urian forces had spotted them and opened fire. During the picosecond it took for the computers to activate the defensive screens, while the force fields of its cage were momentarily short of power, the Monster had attacked with unheard-of ferocity. Using the limited control of time and space it was capable of, it had hurled part of its environment a great distance off, and that had caused the disaster. Proof, if any were needed, that the Monster was by far the most formidable of the weapons employed by Earth in its war against Uria.

Neither Corson nor the Monster had been killed in the initial explosion because the latter was protected by its force-field cage and the former by a shield of the same type, though smaller, which he wore against a possible attack by the Monster. The Archimedes had plunged toward the stormy depths of Uria’s atmosphere. At that moment, in all likelihood, only Corson and the Monster survived on board. Corson, by reflex, had locked his shield to the cage. When the vessel was only a few hundred meters above the ground the Monster had uttered a shrill cry and reacted in the face of danger. It had displaced itself a few fractions of a second in time, carrying part of nearby space along with it. Corson was within that space. Abruptly he found himself, in the Monster’s company, outside the ship and spinning through the air. The resilience of his force shield enabled him to withstand the shock. The Monster, concerned for its own safety, took care of the rest. Corson had landed at its side, and taking advantage of its confusion had managed to run blindly off into the dark.

The whole episode had been an object lesson in the potential of the Monster. Corson knew some of its talents, suspected others, but had never dared hint in his reports that the beast might be this hard to kill.

Imagine, though, an animal hunted by a pack of hounds. Cornered, it rounds on them. The attackers hesitate for an instant. An invisible barrier seems to divide them from the quarry. Then they rush at it. And suddenly find themselves a second earlier. Or two seconds. In the exact spot where they were before crossing that imperceptible line. They can never reach their prey because, time and time again, it hurls them into its past. And when they are dazed enough, the hunted becomes the hunter.

Now imagine that this animal is endowed with intelligence at least equal to the human, reflexes more rapid than a missile’s, a cold cruelty, and implacable hatred for any creature unlike itself.

And you have a faint conception of a Monster.

It could control about seven seconds’ worth of local time, either forward or back. It could snatch from the future a scrap of the cosmos and hurl it a few seconds into the past, or vice versa. And foresee what was going to happen a few moments before it actually did, at least for an unsighted observer such as a human being.

Hence its sudden attack aboard the spaceship. The Monster had known before men or their machines did when the Urian fleet, or the ground batteries, or the accident, would intervene. It had pinpointed with adequate accuracy the picosecond when the bars of its energy cage would be weakened. It had hit out at the right moment, and won.

Or lost. It was a matter of your point of view.

Uria was the Monster’s destination, in any case. After thirty years of fruitless struggle against the Urian Empire, the Solar Powers had devised a tactic which ought to humble those haughty princes. More precisely, ten years earlier they had chanced on an “ally” which had cost them a space fleet, plus a number of individual ships, plus a naval base, plus a planet that had had to be evacuated, plus a system

that had had to be embargoed, plus a lot of casualties. Just how many was a state secret. Without actually intending to, they had experimented on a grand scale with the effects of what was for the time being the Ultimate Weapon.

Assignment: to unleash on a planet of the Empire, preferably the capital world, the worst disaster in the whole of history. Condition: to escape infringing the terms of the Armistice which had ended the hot phase of the war and had been tacitly observed by both sides for twenty years. Method: set the Monster down at a prescribed point on Uria, without being spotted, and let the beast get on with it.

Six months from now, it would give birth to about eighteen thousand of its kind. A year later at most, the capital of the Urian Empire would be panic-stricken. The Princes of Uria would have to overcome their reluctance and appeal to the Solar Powers for help in getting rid of the Monsters, and then in reconstruction. For five or six thousand years that had been the inescapable conclusion of all wars; the victor would rebuild for the vanquished . . . after his own fashion.

Mistake to avoid: giving away the origin of the Archimedes. If the Princes of Uria were able to prove that the Monster had been turned loose by a Solar ship, the Powers would have some difficulty in arguing their case before the Galactic Congress. They might even risk being put under interdiction.

Interdiction: an immediate end to all interstellar traffic, confiscation of merchant ships found outside national space, destruction on sight of vessels of war, outlawry.

Duration: permanent.

For all these reasons the Archimedes had been on a suicide mission. From that standpoint it had been a complete success, barring the survival of George Corson. Not a scrap of the ship remained which would allow it to be identified. The Princes of Uria would be compelled to admit that the Monster might have arrived at their capital world aboard a ship of its own. Only the Terrestrials knew the exact coordinates of its planet of origin and just how puny were the present technological abilities of its species. The sole clue which might allow the Princes of Uria to work out the Monster’s provenance was now Corson himself. If the natives managed to capture him they would have solid proof of Earth’s guilt. The logical solution was suicide. He was satisfied of that. But he lacked the means to destroy himself completely. Granted, the Monster would tear him to shreds, but the traces remaining on the ground would be plenty to convince the Galactic Congress. No abyss on the planet would be so deep that a spoor could not be followed to his body. The only chance Corson had of remaining unidentified lay in staying alive.

At all events, the Monster had been delivered safely.

The night protected Corson from the Monster, whose eyes could not detect infrared or even red, though they saw well enough in the ultraviolet. It was capable of finding its way about in the dark by using sonar frequencies, but it was far too preoccupied with self-pity to bother about tracking him down.

He was trying desperately to work out the nature of the beast’s distress. He was virtually certain that Monsters experienced no counterpart of fear. On their mother world no enemy was known that could seriously endanger their lives. Unacquainted with defeat, they doubtless had never imagined an opponent more powerful than themselves before meeting humans. The only limit on their expansion was imposed by hunger. They could not reproduce except when there was an adequate surplus of food. Without it, they remained sterile. One of the chief problems the biologists from Earth had encountered in accomplishing their project had been how to get the Monster gorged.

Corson could not believe, either, that the creature was hungry or cold. Its metabolism was capable of drawing sustenance from most organic substances and many minerals. The rich pastures of Uria would furnish it with a splendid diet. The climate distantly resembled the most hospitable regions of its mother world. The composition of the air was different, but not so much so as to worry a being which, as experiment had shown, could without apparent harm endure vacuum for hours on end or wallow in sulphuric acid.

And mere loneliness was unlikely to affect the Monster. Experiments which consisted in turning loose Monsters on barren asteroids to study their behavior had indicated how little store they set by the company of their own kind. Given that they were capable of congregating for tasks that exceeded the abilities of an individual, or to play, or to exchange the spores containing their gene equivalents, it nonetheless seemed that they were in no sense sociable.

No, none of his ideas fitted. The voice of the Monster made him think of the cries of a child shut up by mistake or for punishment in a dark closet, feeling himself lost in a vast, unfathomable, terrifying universe full of nightmares and hallucinations, caught in a trap from which he cannot escape by himself. Corson wished he could explain the nature of the trap. But that was impossible. Throughout the voyage he had tried to establish contact with the Monster. He knew it was susceptible to various types of argument, but he had fared no better than his predecessors when trying to carry on a conversation with it. There was one obvious cause: the implacable hostility the Monster displayed toward humans. Why this should be so, no one knew. It might be a matter of smell, color, sound . . . The biologists had tried many ways of deceiving the Monster, all in vain. Its tragedy was that it was too intelligent to be misled by tricks played on its instinctual reactions, and not intelligent enough to identify and tame the mindless powers snarling within which made it good for nothing but to kill.

Having tried a few steps forward, and stumbled, then continued on his knees for some hundreds of meters, Corson, worn out, decided to drowse without entirely relaxing his vigilance. He started awake again after what felt like only a few minutes. His watch told him he had slept for four hours. It was still night. The Monster had fallen silent.

A thick cloud must be crossing the sky, for the stars had vanished from a whole area to his left. It was moving rapidly. It had a sharply defined edge. A huge object, doubtless a flying machine of a type he had never heard of despite having studied all the engines of war employed by the Princes of Uria, was passing soundlessly overhead. It was hard to guess at its height or speed because it was so difficult to see clearly. But when it was directly above him, its black outline on the heavens swiftly grew larger and he just had time to realize that it was going to crush him.

It must be this intruder which had quieted the Monster; it must have been the sudden silence which had awakened him. Knowing what was about to happen a few seconds ahead of time, the Monster had inadvertently warned its unwilling human ally.

Corson felt his belly muscles tense, his blood run chill. He grasped his gun, under no illusions. He did not doubt that the vessel had come to capture him. Determination alone would be useless against a machine so vast. The only course for him to adopt was, once he had been made prisoner, to persuade the occupants of the ship to lure the Monster on board too. Whatever cage or cell the craft was fitted with, that would be all he’d need to do. With a bit of luck the strange ship would be as completely destroyed as the Archimedes, and the Princes of Uria would never find a trace of George Corson’s visit to their world.

Details of the ship emerged from a blur of nothing. A lance of light stabbed down from its black, shiny hull and raked the thicket where Corson was hiding. The Princes of Uria must then have such confidence in themselves that they did not even bother to use a black-light projector. Reflexively Corson trained his gun on the lamp. The underside of the ship was sleek and polished like the surface of a jewel. Its builder had taken esthetic advantage of the geodesics, along which leaves of metal had been attached. This craft did not look in the least like a war machine.

Corson braced himself against a gun bolt, a blast of gas, or the shock of a steel cable around his shoulders. He anticipated the chirping cry of a Urian soldier. But the beam merely focused on him and remained there. The craft descended further, then halted so close that he could have touched its side without getting up. Big ports shone around its circumference. Corson could have tried to break one with his gun. But he didn’t do it. He was trembling, yet at the same time he was more puzzled than frightened by the odd and unmilitary behavior of the craft’s commander.

Doubled over, he walked around the circular hull. He tried to catch a glimpse of the interior through the ports, but they dazzled him, and the only impression he gained of the equipment within was

distorted and vague. He did fancy he discerned a humanoid silhouette, but that was not surprising. From a distance the natives could pass for humanoid enough.

Startled by bright light, he shut his eyes for a moment. A brilliantly illuminated doorway was opening in the ship’s side above a flight of steps suspended on nothing. Corson hesitated, then rushed up them. The door closed again silently as soon as he had passed through, but he had been prepared for that.

“Come in, Corson,” said a voice—a young girl’s voice. ‘There’s no reason to stand about in the corridor.”

That was a human voice! Not an imitation! The Urians would not have been able to fake one so convincingly. A machine might have managed it, but Corson doubted whether his enemies would have added such a finishing touch to a trap he had already fallen into. People at war seldom gave invaders the tourist treatment.

Corson obeyed. He pushed at a half-open door nearby, and it slid back into the wall. He saw a wide room, at the far end of which was a gigantic viewport. He could clearly make out the dark mass of the forest they were flying over and, sparkling at the horizon, a brighter line which he reasoned must be an ocean with the sunrise glinting on it.

He swung around. A girl was looking at him. A sort of veil, or mist, was all she wore. Fair hair framed her smiling face. He could detect no enmity in her gray eyes. She seemed remarkably at ease. It had been five years since Corson had seen anything remotely like a woman apart from the issue plastoids with which you had to make do aboard a ship of war. The ability to reproduce was too critical a resource for women of breeding age to be risked in space. And this one, moreover, was beautiful.

He regained his breath, swiftly reviewed the situation, and allowed his combat reflexes to gain control. It was as though a secondary personality took him over. He snapped, “How did you know I’m called Corson?”

At once the girl’s expression betrayed astonishment mingled with fear. He had put his finger on the crux of the matter. The fact that she used his name might imply that the Princes of Uria knew about the mission of the Archimedes, right down to the identities of the crew. On the other hand the girl was definitely human, body and voice, and her presence on Uria was in itself a total mystery. No surgeon could make a Urian look like that; no operation could re-

place a homy beak with soft lips like those. If the girl had been fully clad he might have felt reservations. As it was, every detail of her figure proclaimed her origin. He could clearly see her navel, something which Urians—hatched from eggs—did not possess. And plastoids were never built to a standard that could deceive a man.

“But you’ve just told me!” she exclaimed.

“No, you called me by name first of all,” he said, feeling as though he were spinning round and round. His brain was working frantically, but in vain. He felt a strong impulse to kill the girl and make off with the ship, but surely she could not be alone on board, and he must know more before he acted. Perhaps he might not in fact have to kill her.

He had never heard any report of humans going over to the Urian side. In a war whose main and perhaps sole basis lay in a fundamental biological difference combined with the ability to inhabit similar planets, there was no future for the traitor’s trade. And—he realized suddenly—he had not noticed the characteristic Urian smell when he came aboard. He was certain he could have detected the tang of chlorine instantly. Even so . . .

“Are you a prisoner?”

He wasn’t hoping that she would admit it, but she might let fall a clue.

“What funny questions you ask!” She opened her eyes wide and her lips started to tremble. “You’re a stranger! I thought— Why should I be a prisoner? Are women kept prisoner on your planet?”

Her expression changed suddenly. He read intense terror in her gaze.

“No!”

She cried out and flinched away, casting around for something to use as a weapon. Then he knew what he had to do. He strode across the room, brushed aside the feeble blow she aimed at him, planted a palm on her mouth and caught her in a wrestling hold. His thumb and forefinger sought the pressure points in her throat. She slumped. A trifle harder and she would have died. He was content to knock her out. He wanted to give himself time to think.

He searched the ship and convinced himself they were alone on board. Fantastic! That a young girl in a pleasure boat—he couldn’t find a single weapon—should be cruising cheerfully over the forests of an enemy planet: it defied belief. He located the instrument panel, but the controls meant nothing to him. A red spot which must represent the ship was moving across a wall map. He recognized neither the continents nor the oceans of Uria. Had the commander of the Archimedes brought them to the wrong planet? Out of the question. The vegetation, the solar spectrum, the composition of the air, were enough to identify Uria, and the attack they had suffered wiped away the final doubt

He glanced out of a viewport. They were flying at about three thousand meters, and as nearly as he could judge at about four hundred k.p.h. In ten minutes at most they would be over the ocean.

He returned to the first cabin and sat down on an ornate chair, staring at the girl. He had laid her on the floor and put a cushion under her head. One seldom finds cushions aboard a warship—embroidered ones, at any rate. He struggled to recall precisely what had happened since he set foot in the ship.

She had called him by name.

Before he had opened his mouth.

She had seemed terrified.

Before he had thought of attacking her.

Partly, it had been the fear he could read in her eyes which drove him to action.

Telepathic?

If so, she knew his name and his mission and knew about the Monster, too. So she would have to disappear, especially if she was in the pay of the Princes of Uria.

But she had retreated even before he thought of overpowering her . . .

She was stirring. He set about tying her up, tearing long strips of cloth from a tapestry. One doesn’t find tapestries aboard a warship. He bound her wrists and ankles, but did not gag her. Also he tried to determine the nature of the garment she had on. It was neither woven fabric nor a gas, but something more like a gleaming mist, so light that it was hard to see. Only at the comer of his eye could he clearly discern its contours. A sort of energy field? Certainly not a force field, anyhow.

The language she had addressed him in was pure Pangal, but that meant nothing. Urians spoke it as well as Terrestrials. Corson had even tried to teach the rudiments of Pangal—that language which proudly claimed to embody the common factors of all intelligence —to the Monster, but without success. As usual.

But it was thinking about the Monster which gave him the key to the puzzle.

This girl must have at least one talent in common with the Monster. She must be capable of foreseeing the future, within limits. She had been aware, the moment he entered the ship, that he would ask her, “How do you know I’m called Corson?” The fact that her terror had decided him to attack her made no odds, merely posed the problem of proximate cause. As did most temporal paradoxes. Those who came in contact with Monsters learned something about temporal paradoxes, generally the hard way. So he could assess the girl’s precognitive range at about two minutes. She was doing better than the Monster, then.

Not that that shed any light on her presence on Uria.

The sun had been up for more than an hour, and they were flying over the ocean out of sight of land. Corson was beginning to wonder what was keeping the Urian fleet when the girl suddenly roused.

“Corson, you’re a brute!” she said. “Attacking a woman who had made you welcome—that was contemptible! We might be back in the barbarian days of the Solar Powers!”

He studied her closely. Although she was writhing in her bonds,

he could read no alarm in her face, only anger. It followed that she knew he did not mean her any immediate harm. Her delicate features relaxed and the rage gave way to cool determination. She seemed too civilized to spit in his face, but effectively that must be what she wanted to do.

“I had no option,” he said. “Like they say, all’s fair in love and war.”

Nonplused, she stared at him. “What war are you talking about? Corson, you’re out of your mind!”

“George,” he said. “George Corson.”

At least she had not foreseen that, the other half of his full name, or at any rate she had not bothered to use it. With deliberation he set about untying her. He realized that that was why her face had relaxed. She let him do it without saying a word. Then she rose in a single movement, rubbed her wrists, confronted him and—before he had time to move—slapped his face, twice. He did not react.

“Just as I thought,” she said scornfully. “You can’t even cog. How could an atavism like you crop up? What use are you? Oh, something like this could only happen to me!”

She shrugged her shoulders and turned away, her gray eyes fixed on the sea over which the craft was soundlessly floating.

Exactly like the heroine of an old teleplay, Corson thought. A prewar teleplay of the kind in which girls would pick up guys by the road, and a lot of more or less dreadful things would happen to them, and generally they wound up falling in love. Myths. Like coffee, or tobacco—or a ship such as this one.

“That’ll teach me to invite people in whom I don’t know,” she went on, as though playing a part in just such a teleplay. “We’ll find out who you are when we get to Dyoto. Until then, you behave yourself. I have influential friends.”

“The Princes of Uria?” Corson suggested sarcastically.

“I’ve never heard of any princes. Maybe in legendary times . .

Corson swallowed hard.

“Is this planet at peace?”

“Oh, only since twelve centuries ago to my knowledge! And I hope it’ll stay that way to the end of time.”

“Do you know any of the natives?”

“Yes, of course. They’re avians. Intelligent, harmless, spend most of their time discussing philosophy. Slightly decadent types. Ngal

R’nda is one of my best friends. Say, who do you think you’re dealing with?”

“I don’t know,” he confessed. That was a strict and literal truth.

Her manner softened. “I’m hungry,” she said. “You must be too, I imagine. I’ll go and see if I’m still capable of fixing something for us after what you’ve put me through.” He could not detect the slightest apprehension in her tone, only friendliness.

“Your name?” he said. “After all, you do know mine.”

“Floria,” she answered. “Floria Van Nelle.”

That’s the first woman who’s told me her name in five years . . .

“No,” he corrected himself silently. “If I’m not dreaming, if this is not a trap, or a hallucination, the three-dimensional full-color delirium of a dying man, then in twelve hundred years, or two thousand, or three thousand.”

She was putting a glass in his hand. He almost dropped it.

When he was full, his brain started to work normally again. He took stock of the situation. He still had no idea what could have happened on Uria except that apparently a state of peaceful coexistence obtained between the millions of humans who lived here and the scarcely more numerous native population. He knew he was bound for Dyoto, an important city, in company with the loveliest girl he had ever set eyes on.

And that the Monster was wandering in the Urian forest, ready to breed, to give birth to eighteen thousand little Monsters who would quickly become as dangerous as their parent. That would be in at most six months, perhaps less if the Monster found plenty to eat.

Now he could work out what had most likely happened. When the Monster hurled itself clear of the ship just before the explosion, it had not made a jump of a few seconds through time, but a journey across millennia. And had dragged George Corson along. The Princes of Uria no longer existed; nor did the Solar Powers. The war had been lost or won, but in any case forgotten. He could consider himself discharged from the service and abandon his soldier’s uniform. Or else he could regard himself as a kind of involuntary deserter, marooned in the future. He was no longer any more than one man lost among the billions of citizens of a galactic federation covering the whole of the Lens and extending towards the Andromeda Nebula. It united planets he would doubtless never go to, linked by a network of transmatters allowing virtually instantaneous transit from world to world.

Now, he had no identity, no past to live down, no mission to accomplish. From Dyoto, he could head for any of the stars he had seen shining in the night sky and there pursue the only profession he knew, war. Or choose another. He could run away, forget Earth, forget Uria, forget the Monster, forget this girl Floria Van Nelle, lose himself for ever in the mazes of space.

And let the new inhabitants of Uria figure out on their own how to cope with the Monster and—soon—its eighteen thousand offspring.

But he couldn’t fool himself. He was aware it would be a long time before he stopped asking himself one all-important question: why had Floria come to pick him up just in time?

Why did she give the impression that she was acting, rather poorly, a role she had learned by heart? Why had she switched from anger, which wasn’t faked, to cordiality as soon as she had her wits about her again?

From a distance Dyoto resembled an enormous pyramid whose base rested on air more than a kilometer above the ground, a jagged cloud along whose sides dark planes flecked with sparkling dots of light were ranged like geological strata on the flank of an eroded mountain. It took Corson’s breath away.

Then the pyramid seemed to disintegrate. The cloud became a labyrinth. The buildings, or machines, which composed the city were widely spaced one from another. A twin river jetted vertically from the earth and ran through the city like a pillar trapped inside an invisible tube. Vehicles flitted along the city’s three-dimensional arteries. Just as the ship carrying Corson reached its outskirts, two major buildings, both cubical in shape, rose skyward and flew off toward the ocean.

Dyoto, Corson told himself, was a fine example of city planning based on antigravity and bearing the stamp of an anarchically conceived society. In his experience the use of antigrav was confined to warships. As for anarchy, that was no more to him than a historical label; it had no place in time of war. Every man, every object, had a role assigned by the system. But in twelve centuries, or however many millennia, there had been time for things to change. At first sight it was clear that antigrav must now be as common as fusion power. Could it itself have become a source of energy? He had heard vaguely about projects of that kind. Antigrav generators aboard warships consumed a hell of a lot of power, but that meant nothing. The forces exerted by one mass on another must also represent a vast energy potential.

Such a city, by contrast with those he was used to, was not a more or less fixed collection of structures. It was a fluid group of them; one could cast or hoist anchor at will. Only the primary function of the city endured, that of bringing people together so they could exchange goods and ideas.

Slowly Floria’s ship climbed along one of the faces of the pyramid. The buildings were so arranged, Corson noted, that even the lowest stories of the city enjoyed a great deal of sunlight. That argued the existence of some central authority, regulating traffic and allotting places to new arrivals.

"Here we are,” Floria said abruptly. “What are you going to do?” “I thought you were going to turn me over to the police.”

Seeming interested, she said, “That’s what would have happened in your time? Well, the lawmen will find you by themselves if that’s what they want. I’m not sure they still know how to carry out an arrest, though. The last one must have happened a decade ago.”

“I—I assaulted you.”

She burst out laughing. “Let’s say I needled you, shall we? And it’s been a terrific experience, keeping company with a man who can’t tell from one moment to the next what you’re going to say or do.”

She walked straight up to him and kissed him on the mouth, then drew back before he had time to clutch at her. He stood there gaping. Then he told himself that what she’d said had the ring of truth. Meeting him had excited her. Well, she might not be used to men like him, but he knew women like her. He had found favor in her eyes because he had used violence against her. So the fundamental characteristics of humanity couldn’t have changed in these twelve centuries even if certain superficial talents had evolved.

He could capitalize on a situation like this.

But something in him rebelled. He wanted to get the hell out. A kind of instinct was urging him to put the maximum possible distance between this planet and himself. The impulse was solidly founded on what he knew was going to happen here. Possibly in twelve centuries—or more—the human race had made enough progress to get rid of eighteen thousand Monsters easily. He doubted it. And he was well aware that if he stayed in Floria’s vicinity much longer he was going to become attached to her in a way that would seriously hamper his freedom of action.

“Thanks for everything,” he said. “If I can do anything in return one day . . . ?”

“You’re very sure of yourself,” she said. “And where are you thinking of going?”

“Some other planet, I hope. I . . . Well, I get around a lot, and I’ve spent plenty of time on this world.”

Her eyes widened a little. “I won’t ask why you’re lying, Corson. But I am wondering why you lie so badly.”

“I enjoy it.”

“Not very much, apparently.”

“I do my best.”

He was aching to put a multitude of questions to her, but he bit them back. He would have to explore this new universe on his own. For the time being he wanted to keep his secret, so he would have to make do with the meager data he had acquired during this morning’s conversation.

“I’d hoped for something else,” she said. “Still, it’s up to you.”

“I can do you a favor anyhow. I’m going to get off this planet.

You do the same. In a few months life here is apt to be intolerable.”

“Go with you?” she countered ironically. “You’re not even capable of seeing one minute into the future, and here you are playing the prophet! Well, I’ll give you some advice in return. Get some new clothes. If you don’t you’ll look very silly.”

Embarrassed, he emptied the pockets of his combat uniform and accepted a sort of tunic which she offered him.

When on Mars, breathe like a Martian . . .

The ship was pulling alongside an aerial jetty now. Corson felt really silly in his new outfit. The craft came to a dead stop.

“Have you an incinerator?”

“A what?”

He bit his lip. "Ah . . . Something which gets rid of refuse.”

“An eraser? Well, of course."

She showed him how the device worked. He rolled his uniform into a ball and tossed it in. The loose-fitting clothes he had put on would adequately hide his gun, under his left armpit. He was almost certain she had spotted the weapon, but that she had no idea of its purpose. The uniform vanished before his eyes.

He went straight to the door, which opened for him. On the point of leaving, he wanted to say something, but words would not come. He made a vague gesture with one hand. For the moment, his mind Was dominated by a single obsession.

He needed somewhere quiet to think out how he could get the hell away from Uria—fast

The landing stage was soft under his boots—correction: under his sandals, now. A pang of alarm struck him as he looked around. He could have stayed longer with Floria, picked up a lot more information ... As far as he could tell, his haste to get away stemmed from an ancient soldier’s reflex: never stay longer than you have to in a temporary hideout. Keep moving, always keep on the move!

So his present behavior was still conditioned by a war over a millennium old, which he had resigned from the night before. But he was aware of something else, too. Floria was young, lovely, and very likely available. He himself came from an epoch of total war, where practically every ounce of human energy was devoted to combat or to the industrial effort which made fighting possible. He was suddenly exposed here to the possibilities of a world where individual happiness appeared to be the only law. The contrast was too much for him. He had left the ship because in Floria’s company he suspected he would not be able to think straight.

He reached the end of the landing stage and studied with mistrust narrow gangways fitted with handrails, steeply slanting ramps. He was worried that he might draw attention to himself by his nervousness, but he soon realized that nobody was likely to notice. In his universe, a stranger was instantly assumed to be a spy even though it

was absurd to imagine that a Urian would risk entering a city held by humans. A spy scare had an additional purpose apart from maintaining security. It kept people’s minds busy. He was cynical enough to recognize the fact.

These inhabitants of Dyoto displayed a lot of courage. They leaped from one ramp to another even if they were twenty or thirty meters away. Corson thought for a moment that they must have miniaturized antigrav units hidden in their clothes, but soon realized he was wrong. At his own first attempt he jumped from a height of three meters, landed with his knees bent, and nearly fell over. He had expected a much more violent impact. Emboldened, he tried a dive of twelve meters or so, and saw coming straight toward him a tiny aircar. The machine had to swerve to avoid him and its pilot turned a face pale with rage or fright. He told himself he must have broken a traffic regulation. He moved on quickly, afraid of finding some sort of patrolman at his heels.

Most of the time the people around him seemed not to be heading anywhere special. They spun and wheeled like insects, darted down three stories, let themselves be swept up by invisible air currents which set them down six levels higher, chatted for a moment with an acquaintance, and continued on their senseless way. From time to time somebody entered one of the buildings that formed the skeleton of the city.

Loneliness overcame Corson some three hours later. He was hungry and he felt tired. His initial excitement had subsided. He had assumed he would locate, without difficulty, a public restaurant or a dormitory, or the two combined, such as existed on all planets occupied by the Solar Powers for the benefit of soldiers and travelers, but he had failed to spot one. He dared not question any of the passers-by. Eventually he decided to enter one of the larger buildings. Beyond its door there was a vast hall. Things were laid out on immense counters. Thousands of people were milling around and helping themselves.

Was it theft to take something from here? Theft was severely punished by the Solar Powers and Corson had been strongly conditioned against it. A society at war could not tolerate such antisocial tendencies. When he found an array of foodstuffs, he stopped worrying. He selected items that resembled what Floria had prepared for him, stuffed them in his pockets, rather expecting to hear an alarm go off, and beat a retreat toward the entrance by a devious route, taking care not to follow for a second time the aisles he had used on his way in.

At the moment when he was about to cross the threshold, a voice made him jump. It was deep, pleasantly inflected, rather friendly. “Haven’t you forgotten something, sir?”

Corson looked about him. Nothing!

"Sir?” the bodiless voice persisted. “Mister—?”

“My name’s Corson,” he muttered. “George Corson.” There was no point in concealing his name on a world where it would mean nothing to anybody.

“Perhaps I have overlooked some formality,” he admitted. “You see, I’m a stranger here. Who are you?”

The most amazing thing was that the people passing by seemed not to hear the voice.

“The accountant for this establishment. Perhaps you wish to speak to the manager?”

By now he had worked out where the voice was coming from: a point in midair, about shoulder height and a meter away.

“I’ve broken a regulation?” Corson said. “I suppose you’ll have me arrested, then.”

“Sir, no credit account has been opened in the name of Corson. If I' m not mistaken, this is the first time you have visited our premises. That is why I took the liberty of addressing you. I trust you will not hold that against me.”

“I’m afraid I don’t have any credit, no. Naturally, I can return what I’ve taken—”

“But why, Mr. Corson? You can pay in cash if you like. We accept currency from any recognized world.”

Corson started. “Would you say that again?”

“We accept money from any recognized world. Any type of currency certificate will settle the matter.”

Dumbfounded, Corson said, “Money? I don’t have any money!” The word burned his mouth. Money for him was an archaic concept, and rather a disgusting one. He knew, as everyone did, that it had been used—long before the war—as a medium of exchange on Earth, but he had never seen the stuff. The army had always provided everything he needed. He had practically never felt the urge to acquire anything other than what he was allotted. He had been led like all his contemporaries to regard money as an obsolete custom, barbaric in fact, inconceivable in an advanced society. It had never for a moment crossed his mind that he would need money when he left Floria’s ship.

“I—uh ...” He cleared his throat. “I could maybe work in exchange for what I’ve taken?”

“Nobody works for money, Mr. Corson. Not on this planet, at least.”

“But what about you?” Corson said incredulously.

“I am a machine, Mr. Corson. Let me suggest a way out of this. While waiting for your credit to be established, could you perhaps name a person who would serve as your guarantor?”

“I only know one person here,” Corson said. “Floria Van Nelle.” “That will suit admirably, Mr. Corson. Forgive me for troubling you. We hope to see you again.”

The voice fell silent. Corson shrugged, annoyed at feeling so upset. What would Floria think when she found that he had embezzled credit from her? Well, that had been a stroke of bad luck. But that voice was what had really shaken him. Was the “accountant” omnipresent here, able to speak simultaneously with a thousand customers, advise them, inform them, tell them off? Were invisible eyes spying on him all the time, hidden as it were by crannies in the air?

He shrugged again. At any rate it seemed that he was free to go.

He located a fairly quiet spot and opened one of the cans. Once again his soldier’s reflexes were at work. While eating he attempted to decide on a course of action. But try as he would he could not picture a future for himself.

The problem of money, to start with. Without money, it would be hard for him to leave Uria. Interstellar trips must certainly be expensive. To the time trap he was in had now been added a space trap. Unless, within six months, he found a way to earn some money.

Not by working, since nobody worked for money here. The more he pondered, the tougher the problem seemed. There was nothing he knew how to do which was likely to interest the people of Uria. Worse, in their eyes he was a kind of cripple. The men and women strolling along the avenues of Dyoto could foresee events about to happen in their lives. He did not share that talent, and had every reason to think he never would. The appearance of this power raised several questions which he reviewed for a moment. Was it due to a mutation, suddenly cropping out and spreading rapidly among the human species? Or was it a latent power which could be developed with special training?

The power implied, anyhow, that in his dealings with the human population here he could never take anyone by surprise. With one exception.

He knew the distant future of the planet.

In six months, a swarm of Monsters would cheerfully and ferociously launch an attack on Dyoto, hunting their victims through a maze of space and time. Perhaps their new talent would enable the humans to enjoy a short reprieve. But nothing more.

It was a good bargaining point. He could warn the central authorities of this planet, advise a total evacuation, or try to perfect the techniques for dealing with Monsters which the Solar Powers had been studying. That was a two-edged sword, though. The Urians might simply decide to hang him.

He threw the empty food packs overside and watched them fall. Nothing slowed their descent. The antigrav field must affect only human beings. Possibly the necessary orders were drawn directly and subconsciously from the nervous system. He was unable to imagine how that might be done.

He rose and started to wander about again. Mission: find the Spaceport, the starship launch station, or the transmatter terminal, and get away, using force if need be. If he were arrested, he could always talk about what he knew.

The layout of the city was becoming clear to him, although it Struck him as extraordinarily haphazard. The military bases of his own day had always been built to the same design. Certain routes were reserved for vehicles, others for pedestrians. Not here. The ability to foresee events—to cog, as Floria had called it—must have influenced the highway code. He recalled the accident he had barely escaped a few hours earlier. That driver had not foreseen Corson getting in his way. Then, in order to cog something, the Urians must have to make an act of will, perhaps focus a kind of inward sight. Or could it be that the power was less well developed in some people?

He tried to concentrate and imagine something that was about to happen. A passer-by: he might carry straight on, turn, go up or down. Corson decided he was going to turn. The man kept on his way. He tried the test again, failed again.

Again. Again.

Perhaps he was failing too often? Perhaps some block in his nervous system was causing him always to make a wrong choice? Perhaps!

Vague recollections of long-ago experiences rose to his mind, premonitions, cruelly clear, which had come true. Like lightning flashes which, at a key moment during battle, had lit up the field of his awareness. Or in the silence of utter exhaustion. Nothing calculated or reasoned out. Just incidents such as one forgot again at once, dismissed as coincidental.

He had always had the reputation of being a lucky bastard. The fact that he was still alive seemed to confirm what his comrades— dead, all dead—laughingly used to say. Had luck become a factor you could measure, here on Uria?

A light floater halted level with him and by reflex he tensed. Muscles taut, knees flexed, he reached toward his armpit. But he did not draw his gun. The machine contained only one passenger, a girl. Empty-handed. Dark. Young and pretty. She was smiling. She must have stopped to talk to him. He had no idea who she might be.

He straightened and wiped the sweat from his forehead. The girl beckoned to him.

“George Corson, isn’t it? Then come along.”

The rim of the floater deformed like cloth, or plastic under a heat beam, to let him board.

“Who are you? How did you know where to find me?”

“My name is Antonella,” she said. “And Floria Van Nelle told me about you. I wanted to meet you.”

He hesitated.

"I know you’re going to get in, George. So let’s not waste time.” He almost turned on his heel. Could one cheat the precog power? But she was right: he did want to get aboard. He had had enough of being alone, and needed to talk to someone. He would have time later to continue his experiments. He climbed into the machine.

“Welcome to Uria, Mr. Corson,” Antonella said with a touch of formality. “I am instructed to greet and guide you.”

“An official assignment?”

“If you like. But I take great personal pleasure in it.”

The floater had gathered speed and was flying off without the girl seeming to pay attention. She smiled; her teeth were magnificent.

“Where are we going?”

“How about a trip along the seashore?”

"You’re not taking me anywhere in particular, then?”

"I won’t take you anywhere you don’t want to go.”

“Fair enough,” Corson said, sitting down on a cushioned bench. And, as they were leaving Dyoto behind:

“You’re not scared. Floria must have told you everything about

“She told us you were a bit rough with her. She doesn’t yet know whether to hold it against you or not. I think what annoyed her most was your walking off and just dumping her. It’s very insulting.”

She smiled again and he relaxed. Without being able to say why, he felt he could trust this girl. If it was really her duty to make strangers welcome, she had plainly been selected with great care.

He turned his head and saw for the second time the enormous pyramidal mushroom of Dyoto, seeming to balance on the two glittering columns of the twin vertical river. The sea, in great slow heaves that indicated a vast ocean beyond, came to gnaw at an endless beach. The sky was almost empty. A faint iridescence, like the ill-defined cloud above a waterfall, surrounded the summit of the city.

“What do you want to know about me?” he asked suddenly.

“About your past, nothing, Mr. Corson,” she answered. “It’s your future which concerns us.”

“Why?”

“You honestly don’t know?”

He shut his eyes for a moment. “No. I don't know anything about my future.”

“I see.” A pause. “Would you like some smoke?”

She was offering him an oval case. Curious, he took from it a cigarette-like tube, set it to his lips, and sucked, expecting it to light of its own accord. But nothing happened. Antonella held an igniter toward him, and at the moment when it uttered its flame a brief and very bright light dazzled him.

“What are you planning to do?” the girl asked in a soft voice.

He passed his hand across his eyes and filled his lungs with smoke. Amazing! This was genuine tobacco—if he hadn’t forgotten what that tasted like after smoking the sad dried seaweed which had taken its place in a world at war.

“Get off this planet,” he said impulsively, and at once bit his lip, too late. A luminous spot was floating before his eyes as though the brilliant reflection the metal shell of the igniter had flashed onto his retinas had stamped them with a tiny and indecipherable design. He suddenly caught on and crushed the cigarette out against the side of the vessel. He pressed his fingers on his eyelids so hard that he saw rockets, whole salvoes of them, and nova stars. His right hand slid toward his gun. That flash from the igniter had not just been a reflection. Its hypnotic effect, probably combined with a drug in the cigarette, had been intended to make him talk. So much for his combat reflexes! They must have been dulled by the placidity of Dyoto. Still, his training had made him able to resist attacks on this level.

“You’re very tough, Mr. Corson,” Antonella said in a calm tone. “But I doubt whether you’re tough enough to get off this world.” “Why didn’t you cog that your little trick would fail?” He heard his voice harsh with anger.

“Who said it had failed?” She was smiling as pleasantly as when she invited him on board.

“All I said was that I plan to quit this planet. Is that all you wanted to know?”

“Maybe. Now we’re sure it really is your intention.’'

“And are you going to try and stop me?”

“I don’t see how we can. You’re armed and dangerous. We merely wish to advise against it.”

“In my own interests, of course.”

“Of course.”

The floater was losing height and speed. Above a small stream it halted, sank down, landed gently on sand. Its rim subsided like melting wax. Antonella jumped to the ground and stretched herself, sketching a dance step.

“Romantic here, isn’t it?” she said, picking up a polyhedral shell that might have belonged to a sea urchin. An alien sea urchin, Corson reminded himself. After weighing it in her hand for a moment, she tossed it into the waves which were washing around her bare feet.

“So you don’t like this world?”

Corson shrugged. “It’s a little decadent for my taste. Too mysterious beneath its placid surface.”

“I imagine you prefer war, violence, plenty of action. Maybe you’ll find some of that if you stay, though.”

“Love and war?” he said sarcastically, recalling what he had said to Floria.

“Love? Why not?”

She had lowered her lashes a trifle and appeared to be waiting for something, her lips apart. Corson clenched his fists. He could not remember ever having seen such a sexy woman, not even at an army rest center. He forgot his past completely and took her in his arms.

“I’d never have thought you could be so gentle, George,” she said in a faint voice.

“Is this the way you always welcome strangers to your world?” His tone reflected dull annoyance.

“No,” she said. He saw tears gathering in her eyes. “No. I suppose our customs must be a lot freer than yours, but. .

“The lightning struck, is that it?”

“You’ve got to understand, George. Got to! I couldn’t stop myself. It’s been such a long time!”

He started to laugh. “Since our last meeting, you mean?”

With an effort she composed her face into something more like its former calm expression.

“In a way, yes, Corson,” she said. “You’ll understand by and by.”

“When I’m a big boy?”

He rose and held out his hand to her. “Now I have an extra reason for getting off Uria,” he added.

She shook her head. “You can’t.”

“Why not?”

“At any transmat terminal, on any world, they’ll arrest you and make you undergo treatment. Oh, they won’t kill you, but you’ll never be the same man again. You won’t have any memories left, and precious few desires. It would be like dying.”

“Worse,” he said slowly. “And is that what they do to all interstellar travelers?”

“Only to war criminals!”

He was aghast. The universe about him seemed full of baffling mist. To a certain extent he could understand the behavior of this girl, no matter how obscure were her motives. After all, it was no more extraordinary than these airborne cities balanced on vertical rivers and populated by madmen flitting about in flying yachts. But what Antonella had just said was at the same time incomprehensible and pregnant with menace.

War criminal? Because I took part in a war that’s been over for more than a thousand years?

“I don’t get it,” he said at last.

“Try, try! Anyway it’s plain enough. The Security Office has no jurisdiction on a planetary surface. They only step in when a criminal goes from one world to another. If you take a transmatter, even to one of the local moons, they’ll grab you. You won’t have one chance in a million of escaping.”

“But why should they want my hide?”

Antonella’s face grew hard.

“I’ve told you once, and I’d rather not say it again. Do you think I enjoy calling the man I love a war criminal?”

He caught her wrists and pressed them as hard as he could. “Antonella, I beg you! Tell me what war—what war?”

She struggled to break loose.

“Beast! Let me go! How do you expect me to tell you that? You must know better than I do! Thousands of wars happened in the past —it doesn’t matter which one you came from!”

He released her. A bright fog danced before his eyes. He rubbed his forehead.

“Antonella, you’ve got to help me. Did you ever hear about the war between the Solar Powers and the Princes of Uria?”

She frowned. “It must have been a very long time ago. The last war which involved Uria happened more than a millennium ago.” “Between the humans and the natives?”

She shook her head. “Certainly not. Humans and Urians have shared this planet for over six thousand years.”

“Then,” he said with relief, “I’m the last survivor of a war which took place more than six thousand years ago. I suppose there’s an amnesty.”

She raised her head and stared at him, her big brown eyes full of astonishment.

“No amnesty is possible,” she said in a level tone. “It would be too easy to abuse it. All you’d have to do, at the end of a war you’d lost, would be to jump far enough into the future to escape retribution. Maybe to start fighting all over again. I’m afraid you underestimate the Office.”

The truth was being borne in on him now. For centuries, perhaps millennia, men had been able to travel in time. And defeated generals, dethroned tyrants, had systematically sought refuge in the past or future rather than endure their enemies’ revenge. So peaceful epochs were compelled to protect themselves against these invaders. Otherwise wars might last for all eternity, interlocking in a cosmic network of alliances slashed across here and there by the indeterminate outcome of battles which were ceaselessly being fought over and over again. This Office Antonella had spoken of supervised the stability of time. It ignored conflicts that broke out on the surface of a single planet, but by its control of communications it prevented any war from spreading to a galactic or historic scale. It was a dizzying task. One had to picture the inexhaustible resources of an endless future before it was even conceivable.

And George Corson, emerging suddenly from the past, a warrior lost among the centuries, had been automatically labeled a war criminal. Images of the fight between the Solar Powers and the Princes of Uria passed fleetingly before his eyes. On both sides the war had been conducted without mercy and without quarter. Back then he would not have wasted a moment on the ridiculous idea that a human might feel sympathy for a Urian. But six millennia or more had passed away. He was ashamed for himself, for his old comrades, for both species, at the kind of evil joy he had experienced when he realized the Monster had been delivered safely.

“But I’m not a war criminal,” he said eventually. “Not exactly. I did take part in a long-ago war, but nobody asked my opinion about it. I was born on a world at war and when I came of age I was put through training and I was told to go into combat. I didn’t try and dodge my responsibilities by jumping through time. I was flung into the future by—well, by an accident, by an experiment that went wrong. I’ll cheerfully undergo any kind of interrogation provided it doesn’t harm my personality. I think I could convince any impartial judge.”

Twin tears shone in Antonella’s eyes.

“I so much want to believe you! You can’t imagine how I suffered when they told me what you were! I’ve loved you since the first time we met. And I thought I’d never have the guts to carry out this assignment.”

He took her by the shoulders and kissed her.

So now he was certain of one thing. He would see her again in the future. He would find her at a time when she had not yet met him. In some fashion he could not fully understand, their destinies were intertwined. Today was the first time he had seen her, yet she had known him already. And the exact opposite was going to happen one day. It was a trifle complicated, but it did make a crazy kind of sense.

“Is there such a thing as a government on this planet?” he asked. “I have some news to pass on.”

She hesitated a moment before answering. He told himself she must have been so upset that she was unable to cog his question.

“A central authority? No, there’s been nothing like that on Uria for nearly a thousand years. Nor on any other advanced world. Governments belong to the primitive period of mankind. We have machines that take care of things like the distribution of goods. And we have a police force. But that hardly ever does anything.”

“What about the Security Office?”

“It supervises nothing but communications. Oh—and, I believe, the opening up of new planets.”

“So who looks after Uria’s relations with the Office?”

“There’s a Council. Three humans and a Urian.”

“Is that who you work for?”

She seemed shocked. “I don’t work for anybody! They asked me to see you, that’s all, and warn you about what will happen if you try to leave the planet.”

“Why did you agree?” Corson said sharply.

“Because if you do try and leave here, you’ll lose your personality, your future will be changed, and you’ll never meet me again.” Her lips trembled.

“That’s a private reason,” Corson said. “But why is the Council interested in me?”

“They didn’t say. I think they believe Uria will have need of you. They’re afraid some danger threatens the planet and they’re convinced that only you can avert it. Why, I just don’t know.”

“I have some idea,” Corson said. “Can you take me to them?” Antonella seemed dismayed by the question.

“That might be rather difficult,” she said. “They live three hundred years ahead, and I myself have no means of traveling in time.”

Corson broke the subsequent silence with an effort.

“You’re trying to tell me you come from three centuries in the future?”

She agreed.

“And what assignment does this Council of yours plan to give me?” She shook her head, her hair swooping around her shoulders. “None that I know of. They simply want you to stay on this world.”

“I can prevent the disaster just by sticking around?”

“Something like that.”

“Very comforting. And at this moment, while we’re talking, nobody is exercising any direct responsibility on this planet?”

“No. The present Council supervises a period of a little over seven centuries. It’s not very much. I’ve heard of Councils on other worlds which have to look after a millennium or more.”

“Well, at least that has the advantage of guaranteeing a stable power structure,” Corson sighed. “And how do you intend to get back to your own age?”

“I don’t know. The idea is that you’re supposed to find a way." Corson whistled. “They’re landing me with more and more problems, aren’t they? Well, we have this much in common, anyhow: we’re both lost in timel”

She took his hand.

“I’m not lost,” she said. “Let’s go back. The light’s failing.”

They returned to the floater, deep in thought and with bowed heads.

“One thing at least is definite,” Corson said. “If you’re telling the truth, I’m going to find some means I don’t yet know about to reach that period of the future that you hail from, and up there I’m going to meet you even before you come to give me this warning. You’ll see me for the first time, I’ll see you for the second. I shall make advances that you’ll find incomprehensible. And at the end of that trip perhaps I’ll make sense of this unfathomable muddle.”

He dropped on the cushions, and sleep overcame him while they flew toward the airborne city, its pyramidal splendor licked by the violet tongues of the sunset.

He was awakened by cries, grinding noises, the clumping of boots on a rough surface, orders shouted in a snarling voice, the spiteful clatter of weapons. It was absolutely dark. The floater was swaying from side to side. He turned toward Antonella, whose face he could not even discern in the inky blackness.

“Has there been an accident?” “No, we're being attacked. I didn’t cog anything but this black cloud, and I couldn’t work out what it was.”

“And what’s going to happen next?”

“I can’t see anything. Just darkness, utter darkness.” There was despair in her tone.

He reached out and squeezed her shoulder for reassurance. But in this total obscurity, no contact, however intimate, could dispel the sense of separation.

He whispered, “I’ve got a gun, you know!”

And in a single continuous movement he drew the weapon from its holster and swept the space around, trigger hard down. Instead of the fierce silver ray he was used to, a weak beam of violet shone from the muzzle. Two hands’ breadths away, it faded into nothing. This must be a force field, tuned to absorb not only light but even the most penetrating types of radiant energy. Within his very body Corson felt a nasty prickling sensation, as though his cells were threatening to lose their grip on each other.

A voice so deep and powerful it was like a blow in the belly boomed from an incredibly distant cave.

“Corson, don’t shoot—we’re friends!”

“Who are you?” he cried, but the words were as shrill as though he were hearing through a tiny, tiny spy mike.

“Colonel Veran,” the voice answered. “You don’t know me, but that doesn’t matter. Hide your eyes—we’re going to lift the screen.”

Corson put away his gun and in the darkness felt for Antonella’s hand.

“Do as he says. Does the name mean anything to you?”

She whispered, “I don’t know anybody called ‘Colonel’!"

“That’s a rank, a military rank. His name is Veran. I don’t know him any more than you do, but—”

Like a lightning flash. Between his fingers Corson saw at first only a blank whiteness, which shortly dissolved into a horde of needles as red as blood that drove through his closed lids. When he was able to open his eyes properly he saw that the floater was hovering in a forest glade. It was broad day. They were surrounded by men in gray uniforms, carrying unknown weapons. Beyond the ring of soldiers he could make out two machines, or two mounds of something, whose details were blurred to his suffering eyes. There were two more like them on each side, and when he turned his head he found two more still at his back. More soldiers were standing guard on them.

Tanks?

Then one of the things moved, and Corson almost cried out.

Those “mounds” were Monsters!

Monsters exactly like the one which the Archimedes had been sent to turn loose on Uria. Creatures so terrifying that human beings of Corson’s day, in that age when war had impoverished language, had been able to invent no other name for them but Monster.

Corson glanced at Antonella. Tight-lipped, she was keeping up a pretty good front.

Now a man in a green uniform left the group of gray-clad soldiers and approached the floater. Three meters away he drew himself up stiffly and said in a sharp voice, “Colonel Veran! Miraculously escaped with the rump of the 623rd Cavalry Regiment from the Aergistal disaster. Thanks to you, Corson. Your idea of setting up a beacon saved our lives. What’s more I see you’ve managed to get hold of a hostage. Fine. We shall interrogate her later.”

“I was never—” Corson began. Then he fell silent. If this alarming person felt he owed Corson a debt, let him go on thinking so.

He jumped down from the floater. It was only then that he noticed the soldiers’ uniforms were torn and stained, and there were deep dents in the blackened masks which covered their faces. Oddly, none of the men in sight appeared to be wounded, even slightly. The reason sprang to Corson’s mind from his past experience.

Casualties get finished off . . .

That name “Aergistal” meant nothing to him. These uniforms were none he recognized. The rank which translated into Pangal as “colonel” must have been used for fifteen thousand years at least. This Colonel Veran might have emerged from any battle fought between Corson’s time and the present, although the fact that his men used trained Monsters did indicate that he must come from a period fairly long after Corson’s own. How long would it have taken to communicate with the Monsters, train them, following the first tentative experiments by the Solar Powers—ten years, a hundred, a thousand?

“What was your rank?” demanded Colonel Veran.

Instinctively Corson straightened to attention. But he was grotesquely aware of the unmilitary nature of his dress. And of the situation. He and Veran were no more than ghosts at this point in time. As for Antonella, she had not yet been bom.

“Lieutenant,” he said in a dull voice.

“I promote you captain,” Veran said solemnly, “by virtue of the authority bestowed on me by His Serene Highness the Ptar of Murphy!”

His voice became relatively cordial as he added, “Of course you’ll be made a field marshal when we’ve won the war. For the moment I can’t grant you a rank higher than captain because you’ve served in a foreign army. Speaking of which, you must be very pleased to have found a proper army again, a bunch of tough and reliable men. The short time you’ve spent by yourself on this world can’t have been much fun for you.”

Leaning close to Corson, he spoke in a lower tone.

“Do you think I could pick up any recruits on this planet? I could do with about a million men. And I’ll also need two hundred thousand pegasones. We can still save Aergistal!”

“I don’t doubt it,” Corson said. “But what’s a pegasone?”

“Our mounts, Captain Corson!” With an expansive gesture Veran indicated the eight Monsters.

“Oh, I have some great projects in mind, Captain,” he went on. “Great projects! I’m sure you’ll want to join me. In fact, after I’ve retaken Aergistal, what I plan to do is land on Naphur, take possession of the arsenals there, and dethrone that lousy crot the Ptar of Murphy!”

“To be quite candid,” Corson said, “I can’t see you finding many recruits on this planet. As for pegasones, though . . . Well, there’s one roaming around in the forest, but it’s completely wild.”

“Wonderful!” Veran said. He took off his helmet. His scalp had been shaved; now the hair was starting to grow again, it looked like a pincushion. His gray eyes, very deep-set, made Corson think of hard stones. His face was brown with a lifelong tan, crossed here and there by the marks of old scars. His hands were hidden by gauntlets of shiny flexible metal.

“Let me have your gun, if you please, Captain Corson,” he said.

Corson hesitated a moment. Then he offered the weapon butt-first to Veran, who took it with a brusque gesture. He looked it over, weighed it in his hand, and smiled.

“No more than a toy!”

He seemed to ponder awhile. Then he tossed it back to Corson who, taken by surprise, almost dropped it.

“In view of your rank and the signal service you performed for us, I think I can let you keep it. It goes without saying that it will be useless except against our enemies. But as I’m afraid it may not be enough to protect you, I’ll assign you two of my men.”

He beckoned, and two soldiers wearing light metal collars tramped forward and stood to attention.

“From now on you’re under the orders of Captain Corson here. Make certain he doesn’t fall into an ambush if he leaves the camp perimeter. And as to this hostage of his—”

“She will remain my responsibility, Colonel,” Corson cut in.

Veran’s hard eyes rested on him for a second.

“For the time being that is doubtless preferable. Just make sure she’s not allowed to wander around the camp. I don’t like breaches of discipline. Good, you may go.”

The two soldiers flanking Corson spun on their heels. Helpless, he copied them, giving Antonella a shove for the sake of appearances. They started to march away.

“Captain!”

The harsh voice of Veran stopped them short. It was tinged with sarcasm.

“I must say I wouldn’t have expected to find a soldier of your caliber so . . . sentimental! I’ll see you tomorrow.”

They moved on. The soldiers walked like robots, their rhythmical paces showing how their discipline was surviving their fatigue. Unconsciously Corson fell into step. He had no illusions about his status, despite his weapon and his escort—or rather because of them. He was a prisoner.

The soldiers led them toward a group of gray tents which men were setting up with brisk well-drilled movements. Beforehand, they had carefully sterilized the surface of the clearing. The dry ground was covered with a thin carpet of ash. Where the Ptar of Murphy’s troops had passed, grass must have a lot of trouble growing again.

One of the soldiers lifted the flap of a tent which had already been guyed and indicated that they were to enter. Inside, the furniture was basic. Inflatable chairs surrounded a metal plate floating on air which served as a table. Two narrow bunks completed the list. But the sparseness of this setting made Corson feel more at ease than the luxury of ornate Dyoto.

He let his mind wander for a moment. How would the inhabitants of Uria react to this invasion? Although Veran’s troops were few in number, it was certain they would meet with no serious resistance. Naturally, by one means or another the news would reach the

Council in the future, but they had no army. Perhaps they had already been wiped out. Question: how could a government survive in the future when the past it sprang from had been effectively annihilated? The Urians might never have considered that problem, but it looked as though they were going to find out the answer even before they realized it was a problem. In some ways this immediate threat overshadowed the menace of the Monsters which Veran’s civilization appeared to have tamed under the name of—what was it?—“pegasones.”

And here was something else far too extraordinary to be a coincidence. Veran had popped out of nowhere, claimed to know him, and said he needed two hundred thousand pegasones. In less than six months, if he managed to catch the offspring of the Monster which Corson himself had helped to dump on Uria, he would have eighteen thousand of them. In less than a year he could have even more than he was asking for. Under favorable conditions Monsters reproduced rapidly, and took only months to reach full growth.

No, there wasn’t a chance in a billion that Veran had arrived here by accident. But why should he need a wild pegasone?

Ah! Maybe because . . .

Maybe tame pegasones couldn’t reproduce? Back on Earth, long ago, oxen had been used for pulling carts and plows. Thanks to a minor operation, they were far more docile than a normal bull, which was a ferocious beast. It would account for everything very neatly if Veran’s pegasones had undergone some similar treatment. Certainly it would explain why he needed a wild—undoctored—Monster.

At last Corson turned his attention back to Antonella. She had sat down on one of the inflatable chairs. She was staring at her hands. Flat on the metal plate, they were trembling slightly. Now she glanced up and waited for him to say something.

He sat down opposite her. Her face was drawn, but she was showing no sign of panic. Altogether she was behaving much better than he had expected.

“There’s a good chance that someone’s eavesdropping on us,” he began abruptly. “I’ll say this to you anyway. Colonel Veran strikes me as a reasonable type. This planet needs to be put to rights. I’m sure nothing will happen to you so long as you respect his authority, and mine. Moreover your presence may be useful to his plans.”

He hoped she understood that he was not betraying her and that he would do all he could to get them out of this with whole skins, but that he could not say anything else for the time being. Veran would have other matters on his mind apart from spying on them, but he was not the sort of person to take risks. If Corson had found himself in Veran’s shoes, he would certainly have bugged this tent.

A soldier lifted the entrance flap and cast a suspicious eye around the interior. A second wordlessly brought in two platters and set them on the table. Corson recognized their contents at once; military rations had scarcely changed. After a couple of false starts he showed Antonella how to heat the cans by breaking a seal and then how to open them without burning her fingers. Cutlery was built into the cans, and he ate with a good appetite. To his great surprise Antonella copied him without hesitation. He was beginning to develop a certain respect for these Urian civilians.

Naturally their precog talent must help them to keep their heads. It warned them of imminent danger, so perhaps they could cause Veran’s soldiers more trouble than they were expecting.