CHAPTER VI

SADDLES

RIDING SADDLE, ITS NAMES, SHAPE, COMPONENT PARTS AND VARIOUS ATTACHMENTS—LATTER’S NAMES AND USES—MERITS OF SINGLE RIG AND DOUBLE RIG COMPARED—FURTHER SADDLE ATTACHMENTS, THEIR NAMES AND USES—CAMPING AND CAMP-COOKING—STILL FURTHER SADDLE ATTACHMENTS—FONDNESS FOR SADDLE—SADDLING—ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF STOCK-SADDLE—WESTERN RIDING RECORDS.

THE riding saddle of the cowboy merits description, not only because it was the cowboy’s work-bench or his throne, according as one cares to picture it, but also because one cannot understand the puncher’s ability to ride the bronco except one understands the saddle.

Unless there had existed that particular form of saddle, no man could have ridden the Western horse in the Western country under the conditions that obtained long years ago. There would have been no cowboys and no ranches. The plains would have been forced to wait for their empeopling until the unadventurous farmer slowly had pushed Westward. The course of Western history was determined by that saddle.

The riding saddle universally used upon the Range was of the type which, throughout the West, was known as “cow saddle,” “Range saddle,” or, more commonly, as “stock-saddle,” and in the East was called “Mexican saddle,” “Western saddle,” or “cowboy saddle.” It perhaps should have been termed Moorish rather than Mexican, for, in almost its present basic form, the Moors carried it from Africa to Spain over a thousand years ago.

The flat English saddle the cowboy termed a “human saddle,” “kidney pad,” or “postage stamp.” He regarded it as a token of effeteness, not as an accoutrement for a horse.

All stock-saddles were alike in fundamentals, though they varied in incidental details.

The height and angles of the horn and cantle, and whether the seat were short or long, wide or narrow, whether it were of approximately uniform width or more or less triangular, whether it were level or sloped upward toward either the horn or the cantle or toward both, whether the horn were vertical or inclined forward, and whether its top were horizontal or were higher at its front edge than at its rear were all matters purely of the rider’s choice; save that the cantle had to be high enough to prevent the lariat-thrower from slipping backward when his cow-horse after the throw squatted on its haunches and braced itself. Also followers of the Texan custom of fastening the lariat’s home end to the horn before the lariat was thrown required at least a fairly high horn. Such men had to have not only the space thus occupied but also additional room for “snubbing,” because, the instant the lariat caught its prey, the lariat had to be wound for a few turns around the horn; i. e., to be snubbed.

The several slight variations in shape created special names; and a saddle was designated, according to the form of its tree, as California, Brazos, White River, Nelson, Oregon, Cheyenne, etc.

The American ranchmen’s saddles were built by professional manufacturers and not, as commonly in Mexico, by the cowboys themselves.

Extremely stout construction was required to withstand successfully the terrific strains from roping.

Upon the front end of a strongly built hardwood “tree,” comprised of longitudinal “fork” and transverse “cantle,” was bolted a metal horn; and the whole, covered with rawhide, was fastened down onto a broad, curved, leathern plate which rested on the horse’s back. This plate in its entirety was called the “skirt,” unless one preferred to differentiate and to refer to the half of the plate on the horse’s left side as one skirt, the “near” or “left” skirt, and to the half on the horse’s right side as another skirt, the “off” or “right” skirt, and thus, when mentioning the two halves collectively, to term them as “skirts” instead of as a skirt.

Synonyms for skirt and skirts were respectively “basto” and “bastos” (from Spanish “basto,” a pad or a pack-saddle), though some men restricted these latter terms to the leathern lining of the skirt, a lining known also as the “sudadero.”

On each side of the horse there lay on top of the skirt a leathern piece which was shorter and narrower than the skirt, fitted closely around the base of the horn and cantle, and had its outer edges parallel with, but well inside of, the borders of the bottom and rear edges of the skirt. This leathern piece was the so-called “jockey.” It usually was in two sections, its portion forward of the stirrup-leather being termed the “front jockey,” while so much as was aft of the stirrup-leather was styled the “rear jockey.”

The composite structure fitted onto the horse’s back in the same way as would have done a headless barrel if halved lengthwise, and to the entire barrel-like portion of the saddle was colloquially applied the term bastos, although that term had technically the more restricted meaning stated above.

In infrequent instances the skirt and the rear jockey extended backward no farther than to the cantle, and then there was sewn to the latter’s base an “anquera,” a broad plate of leather which covered the otherwise exposed portion of the horse’s hips, and protected the clothing of the rider from his animal’s sweat.

TOP LEFT: SPADE BIT. TOP RIGHT: “SINGLE RIG” STOCK SADDLE, NELSON TREE. BOTTOM: SPUR WITH BUCK HOOK.

The skirt of usual size stretched from the horse’s withers to his rump, and well-nigh half-way down both his flanks. It had so much bearing surface that the saddle tended to remain in position even without the aid of a “cinch.” A large skirt was necessary when riding buckers or when roping; but for ordinary pottering about a few ranch owners used a saddle the skirt of which was much curtailed.

Whether the saddle should contain a “roll” was a matter of the rider’s individual choice. Some men used the attachment, others did not. A roll was a long welt which stuck out for a third of an inch or more from the front face of the cantle just under its top rim. This cornicelike addition tended to keep the rider from sliding backward out of the saddle during roping and from moving skyward when his pony was bucking.

The saddle was attached to the horse either by one “cinch” passing under the animal at a point approximately even with the stirrups, or by two “cinches,” respectively designated as the “front” and the “hind” or “rear cinch,” and passing one just behind the animal’s front legs and one some twelve inches further to the rear. The saddle of two cinches was designated technically as “double-rigged” or “double rig”; popularly and in pistol-maker’s phrases as “double fire,” “rim fire,” or “double-barrelled”; while the saddle of one cinch had, as its corresponding terms, “single-rigged,” “single rig,” “single fire,” “centre fire,” and “single-barrelled,” and often was also called “California rig,” this last because Californians commonly used but one cinch.

However if a person, while using colloquial language, wished to make technical subdivisions among single-cinched saddles, he would limit “centre fire” to the saddle in which the cinch was either slightly behind the stirrups or, at most, even with them, and would specify as “three-quarters” rig the saddle in which the cinch was in a slightly more advanced position.

Some Texans called the cinches “girths,” and the rearward of them the “flank girth.”

Whether a saddle should be single or double rigged was a matter of its owner’s preference. The single as compared with the double was more easily put on and taken off, was a bit more flexible in riding motion, but it was more apt to shift position during roping and bucking and upon steep trails.

Riders differed greatly in the direction and force of the thrusts which they imposed upon their saddles. With creating this result, the men’s weights in actual pounds had but little to do. The controlling factor was the method of sitting the saddle. Some riders of however much or little poundage ever kept themselves not only in balance upon the horse, but also in balance with it. Such riders made no pulls or pushes that by antagonizing the horse’s movements subjected the saddle to twisting or dislodging strain. Horsemen of this type could go for miles without retightening cinches, rarely galled their horses’ backs, always could ride their steeds long distances without an undue tiring of the brutes, and, save in roping or bucking or when upon steep “side hills,” little needed to care whether their cinches were loose or taut. Such men were called “light riders.” They each might weigh two hundred pounds and yet “ride light.” Of such men, some used a saddle with single rig; others preferred the riding motion of the double rig, or thought the latter a more prudent risk and so employed two cinches.

Still other riders were by the nature of their saddle-sitting forced to employ the double rig, and thus to “carry their pony in a shawl strap.” These latter riders would on occasion get out of balance, and would rectify themselves by impulsive twists and yanks. They would sway a bit across and not in strict accord with the line of the horse’s motions. All this would tend to divert the saddle from its normal position. Such riders “rode heavy,” had frequent cause to taughten latigos, and caused many a saddle sore upon their ponies’ backs. These men could cling to the bucker and throw the rope as successfully as could their “lighter-riding” brothers, but they “gimletted” or “beefsteaked” far more horses’ backs and tired far more ponies.

Finally, in certain regions, the prevailing type of local horse had a chest so short and sloping as to give insufficient anchorage to but a single cinch; while, in other regions, the shortness of the corresponding horses’ “barrels” gave little room for the double rig.

Users of double rig were careful to obey a regulation prescribed by horses and requiring that the front cinch be tightened before the rear one be pulled upon. This rule was strictly enforced by the animals, which, upon its infraction, waited only till the offender had mounted before they went into executive session. Many a tenderfoot, unmindful of this order of procedure, has “hit the ground,” “sunned his moccasins,” or “landed,” which is to say, in other forms of Range English, has been “spilled,” “chucked,” or “dumped,” in any case to hear that conventional, derisive call: “Hi there! You’ve dropped something.” Many a competent rider has been furnished with conclusive if circumstantial evidence that, during his absence, cinches had been tampered with.

Sometimes with a double rig the cinches, to avoid a sore, or more firmly to grip a sloping chest, were crossed below the horse, making a letter X.

Galled backs and cinch cuts were common, but usually were ignored by the riders, who credited the ponies with having iron constitutions. Certainly the animals seemed to suffer little pain from their skin abrasions.

Usually the under surface of the bastos was smooth. If so, there was put between it and the horse’s back some form of padding, either a shaped pad called a “corona” or else, more commonly, a folded blanket; and under the corona, or blanket, for ventilating purposes was placed a gunny-sack. In some saddles the bastos was lined with woolly sheepskin, and in such case the padding was omitted.

The “cincha” or, as usually termed, the cinch was a broad, short band made of coarsely woven horsehair or sometimes of canvas or cordage, and terminating at either end in a metal ring. On each side of the saddle-tree was attached, for each cinch, a second metal ring called the “rigging ring,” “tree ring,” or “saddle-ring,” and from which hung a long leathern strap called a “latigo.” This strap, after being passed successively and usually twice through both the cinch ring and the corresponding tree-ring, was fastened below the latter by much the same method as that in which the present-day masculine “four-in-hand” necktie is knotted. The latigo on the saddle’s off side was permanently left thus fastened, and, in saddling and unsaddling, operations were restricted to the strap upon the near side.

A variation from this method of fastening the latigo was often used on the near side during the breaking of a horse. A wide, metal buckle offered a speedier means of attachment, and haste was desirable when the steed was plunging.

While camped within a forest, punchers had carefully to guard their latigos, because, for some inscrutable reason, the latter bore to porcupines the same relation that candy does to children. It was no uncommon thing to see a dismounted puncher, when not using his saddle as a pillow, hang it from a limb or place it on a pole fastened horizontally and high above the ground.

The rough cinch adhered well to the horse’s body and offered a good hold to the rowels and hooks of the spurs. While the cinch was, strictly speaking, merely the broad band, the term customarily was applied to the combination of both this band and its own two latigos.

Despite the stout material of the cinch and latigos, one of them occasionally would break under the strain of bucking, whereat both saddle and rider would disappear from the horse’s back. Out of this not infrequent occurrence arose the myth of the prudent cowboy who, in his cinch, substituted lead pipe for woven hair.

From each side of the saddle hung vertically, in unequal lengths, the two leaves of the “stirrup-leather,” which was a broad strap looped through the saddle’s tree. The end of the longer leaf was passed through the stirrup’s top, and then was made fast to the bottom of the shorter leaf. A buckskin thong, threading a series of holes in the two leaves, provided means of fastening and ability to adjust length; a thong, instead of a buckle, because so far as possible metal was excluded from the saddle. The cowboy not only wished his outfit to be susceptible of immediate repair, but he had faith in the durability of leather and none in that of metal. He might countenance the use of buckles upon saddles used for breaking horses in the corrals near the ranch-house, but he wished no buckles under him when he was riding far afield.

It was this reliance upon simplicity as conducive to sureness that made him prefer his pistol to be of single, rather than of the slightly more complex double action.

Each stirrup-leather hung, as already stated, from the saddle’s tree. These two leathers at their starting-point almost met behind the horn, and, severally leaving, one to the saddle’s right, the other to the saddle’s left, rested in shallow grooves cut in the wood of the tree. In some saddles, the seat’s leathern covering, starting forward from the cantle, went only to this groove’s rear edge. In other saddles, this covering extended over the entire seat and completely hid the upper portion of the stirrup-leathers. Technical names were given to these two forms of seat covering. They were respectively “three-quarter seat” and “full seat.”

Where each stirrup-leather emitted from the saddle’s side, was overlaid a flat leathern plate. This plate, known indiscriminately as the “seat jockey” or “leg jockey,” shielded the rider’s leg from chafing.

Sewn to the back of each stirrup-leather was a vertical, wide leathern shield, the “rosadero”; sometimes, though incorrectly, called the “sudadero.” It protected from the horse’s sweat and offered stout defense to the rider’s leg.

At the bottom of each stirrup-leather, was a stirrup made of a wide piece of tough wood bent into shape, bolted together at the top, and so sturdy as to defy crushing by a falling horse. Into the stirrup went the rider’s foot clear to the latter’s heel, his toe pointing inward and either horizontally or downward. The sides and front of the stirrup were ordinarily enclosed by a wedge-shaped, leathern cover open toward the rear. The technical name of this cover was “tapadero,” though colloquially this almost always was shortened into “tap.”

Commonly each side of each of the “taps” was in the form of a triangle with apex pointing downward, and was so long that this apex barely escaped the ground; but some men used “taps” which, following the historic Spanish model, were shaped somewhat like horizontally laid coal-scuttles. The “taps” prevented the rider’s feet from passing completely through the stirrups, being snagged by brush, or being bitten by a savage horse. When long and flapped under a ridden steed, they were of no small use as a whip.

“Open” stirrups, i. e., “tapless” ones, were rarely seen upon the Range.

From each side of every saddle hung four sets of thongs, two thongs in each set. One of these sets was at the saddle’s front, one near its rear, while the other two were spaced so that the rider’s leg just passed between them. The two sets of rear thongs embraced whatever might be laid across the saddle behind the cantle, almost invariably the “slicker,” which was a long rain-coat of yellow oilskin such as coastal fishermen wear; though in the Southwest the thongs instead of this sometimes confined a Mexican “serape.” The front and side thongs held any package of the moment.

If a cowboy were starting on a trip which, while forcing him to camp overnight, did not call for many supplies and a consequent pack-horse, he would, nevertheless, not limit himself to the traditional Hudson Bay Company’s ration of a rabbit track and a cartridge, but would insert within the folds of the “slicker” tied at his saddle’s rear the journey’s necessaries. These were a frying-pan, some flour, bacon, coffee, salt, and, as a substitute for yeast, either a bottle of sour dough or a can of baking-powder.

When halting time arrived, the camp was pitched wherever both forage for the horse and drinkable water met. The water, though drinkable, was not always pleasing, for it might taste somewhat of sheep, contain the carcass of a steer, or be girt by banks marked with the telltale white of alkali. It might be so full of sand as to demand admixture of juice from a cactus leaf before showing clearness. It might be so warm as to suggest the betterment of cooling in a porous earthern jar clad in a wet blanket and hung aloft for evaporation’s chilling aid. Will power, hard boiling, and a cactus leaf were available to do away with unpleasant thoughts, with ptomaine dangers, and with floating sand, but the earthern jar would be at the distant ranch and unattainable. Thus the uncomplaining cowboy sometimes, as he said, “drank his cold water hot.” Fortunately most of the Western waters were not of this unpleasant sort.

Occasionally, in the desert, water was either non-existent or else so alkalinely saturated as hopelessly to “rust the boilers” of whoever drank it. In the latter case, although the horses were left grimacingly to gulp the biting fluid and run the risk of being “alkalied,” the men might have recourse to canned tomatoes. The liquid portion of the can’s contents assuaged thirst and counteracted the effect of the already swallowed alkali dust, while the solid vegetable wiped across one’s face would heal the bleeding cuts which that cannibalistic dust had made. A tomato might occasionally be pressed against a pony’s lips for their comforting.

The can-opener was irresistible, since it was a pistol fired horizontally at the can’s top edge.

The pitching of camp was a simple process. It consisted of stripping the saddle and bridle from the horse, of turning the latter loose to graze either at the end of a picket rope or within the grip of hobbles, and finally of building a fire. Lighting the fire was not always an easy matter, for matches might be wet or lost. Then it would call for powder from a dissected cartridge, and the igniting of it by a pistol-shot. Careless aiming might “hang the kindlings on the scenery.”

If, as was usually the case, the camp’s coffee were unground, its beans were mashed on a rock with the butt of a pistol. The resultant mixture of vegetable and mineral substances was set aside until the frying-pan should have cooked, first, bread and, next, bacon.

The bread was quite eatable. With a thick batter spread thinly over the bottom of the pan, the latter was laid upon hot coals for a moment and until a lower crust had commenced to form. Then, tipped on edge, it was held far enough from the fire for a little heat to reach it and to raise the loaf. This achieved, the pan, still on edge, was pushed to within baking distance of the coals, and was left there until the pan’s contents were done.

The thus baked bread, the historic “frying-pan bread” of the West, vacated the pan, and into the latter went strips of bacon. When these had been fried, the pan was rapped against a rock or tree, to expel such of the grease as readily would leave, and then received a charge of water and the coffee-gravel mixture. When the boiling fluid was fairly well covered with fat melted from the utensil’s sides, the dose-like beverage was ready for consumption.

There might be a slice or two of jerked meat from either beef or elk, or else, long years ago, from buffalo.

All this crudity was due not to epicurean depravity, but entirely to the restricted transportation facilities which beset the cowboy as well as the scout, the trapper, the prospector, and the explorer.

The menu of the puncher upon his travels rarely became more extensive than the one described above. A pack-horse, when there was one, indicated quantity rather than variety of food. But it did insure the presence of a coffee-pot.

The lee side of a rock or bush, the saddle for a pillow, the slicker and horse blanket for a covering, a pile of wood for replenishing the fire, collectively made the bedroom and its furnishings.

“The moon now cleared the world’s end, and the owl

Gave voice unto the wizardry of light;

While in some dim-lit chancel of the night,

Snouts to the goddess, wolfish corybants

Intoned their wild antiphonary chants—

The oldest, saddest worship in the world.”1

Tents and extra bedding, because of their troublesome carriage, were almost unknown even in winter. In the latter season, burrowing under the snow protected the sleeper from the wind, while logs placed side by side atop the snow made a platform for the fire.

In cold weather the puncher, when thus afield, customarily took to bed with him his horse’s bridle, that the bit might be kept warm and the horse be spared the pain which mouthing frigid metal would have caused.

Camping in the colder climates was often a trying process marked by nocturnal contests between soporific desire and rheumatic pains, a contest which vacillated according as a sleepy hand dropped fuel upon the fire or the embers chilled.

However, the topic under consideration is the cowboy’s saddle and not his troubles.

There might be at the base of the saddle’s horn a “buck strap,” which was a loop that offered a convenient hand-hold during pitching. Its owner never bragged about its presence. Top riders scorned it, and excluded it from their saddles.

Not infrequently a pair of leathern pockets bestrode the saddle, sometimes behind the cantle, more rarely at the horn. These receptacles were called either “cantineses” or saddle pockets.

The word “cantineses” was used also figuratively, and in colloquial usage was extended to include any heterogeneous medley of small objects. In this latter sense and particularly when qualified, as often it was, by the word “little,” the expression was equivalent to the homely New England phrase, “small contraptions.”

If the saddle were being used in desert country, then from the horn might hang a pair of felt-covered, metallic canteens, or two waterbottles of leather or of coated canvas.

The leather of the entire saddle, inclusive of taps and stirrup-leathers, usually was covered with handsomely impressed designs of leaves and flowers. A saddle, if so decorated, would cost, in the decades of the seventies and eighties, some fifty dollars. In the Southwest, occasionally not only was silver laid into the groundwork of the impressed designs, but both the horn and cantle were subject to be ornamented with precious metal. Then the cost assuredly mounted. Ten months’ wages often went into decoration. At least one ranch owner had a horn and cantle each of solid gold.

Often on the cowboys’ saddles there was applied a homemade ornamentation consisting of brass nails or, again, of rattlesnake skins plastered flat and permanently stuck fast by their own glue.

The saddle’s coloring was usually light brown; but sometimes, and especially in the less expensive saddles, it was cherry-red.

Each saddle best fitted its special owner, for it gradually acquired tiny humps and hollows that registered with his anatomy, and induced both comfort and security of seat. These little mouldings, which suited well the owner, would often fight the contour of a stranger’s legs. Wherefore each man swore by his own saddle and at all others. Texas Ike, in good faith and with generous impulse, said: “Jim, don’t bother to get your saddle. Ride mine. It’s the best that ever came out of Cheyenne. It’s as comfortable as a trundle-bed.” Jim mounted, squirmed, grunted, and in equally good faith remarked: “Tex, where in hell did you ever find this Spanish Inquisition chamber anyhow? You must be using it like the priests wore hair shirts.”

A cowboy so valued his saddle, particularly after it had been broken in, that he almost never would part with it. He has gone so far as, in a poker game, to lose his money, gun, chaps, horse, and even shirt, and then, with saddle on his back, to “strike out” for the ranch still thoroughly cheerful and with “his tail up.” Even such punchers as upon completion of the Texas Drive returned to Texas by rail instead of on horseback carried their saddles with them.

Moreover, it was a bit disgraceful to sell one’s saddle. It was akin to disposing of the ancestral plate and family jewels. The phrase “He’s sold his saddle,” became of general usage, and was employed in a figurative way to denote that anybody in any calling had become financially or morally insolvent. Years ago in a little school at Gardiner, Montana, a small, tow-headed youth, when asked by the teacher as to who Benedict Arnold was and what he had done, replied: “He was one of our generals and he sold his saddle.”

Because the saddle from its shape and large bearing surface had so good a hold on the horse’s back, riders usually, except when on fractious animals or in a mountainous country, let the cinches sag loosely. This gave comfort to the lungs within the confining straps. The horses aided in procuring this sag, for Western steeds, when being saddled, puffed themselves like adders at the first pull on the latigo. They might be momentarily thrown off their guard by a kick behind the ribs, but the beasts reconcentrated their attention upon inhaling before the strap could be pulled again.

To “cinch up” any bronco (he was “cinched up,” not merely “cinched”), one had to place one’s foot against the brute’s ribs and, in the case of the front cinch, to pull with almost all one’s strength upon the latigo, meanwhile standing ready to dodge precipitate bites from the indignant head-tossing bronco. Pulling upon the rear cinch exacted much less muscular effort, but much greater circumspection; for bites were apt to be more frequent, and good measure might throw in a kick or two.

The cowboy’s saddle was not suitable for racing. It was too heavy, thirty pounds at the very least and usually forty pounds or over. But the usual and useful gaits of the Range were not of racing speed. They were the running walk, the jiggling trot, the lope, with now and then a short dash after errant live stock.

The cowboy’s saddle well-nigh inhibited jumping of hurdles. Its occupant, the instant he assumed the posture necessary to encourage his horse to “take off,” lost his balanced seat, and was, from the saddle’s shape, unable to cling, as on the English tree, by constrictive force. But there were few hurdles upon the Range.

Nor could a rider, when in this saddle, rise to the trot. But the cowboy did not wish to rise. In his own language, he “postage-stamped” the horse.

Nevertheless the saddle was ideal for the service in which it was used.

It made wholesale roping possible. It made possible riding the American bucker. It made possible long and compulsory rides on animals so indifferently broken as to have been unserviceable under a seat less secure. It made possible the “night herd,” because it permitted the tired cowboy to sleep while still ahorse. Repeatedly men on herding duty were, through storm or other circumstance, kept upon their task for forty-eight consecutive hours. In the wild nights of winter, the most courageous puncher did not dare to permit his pony chance of escape, so there were cat-naps in the saddle, rather than more restful sleeps beside a picket pin.

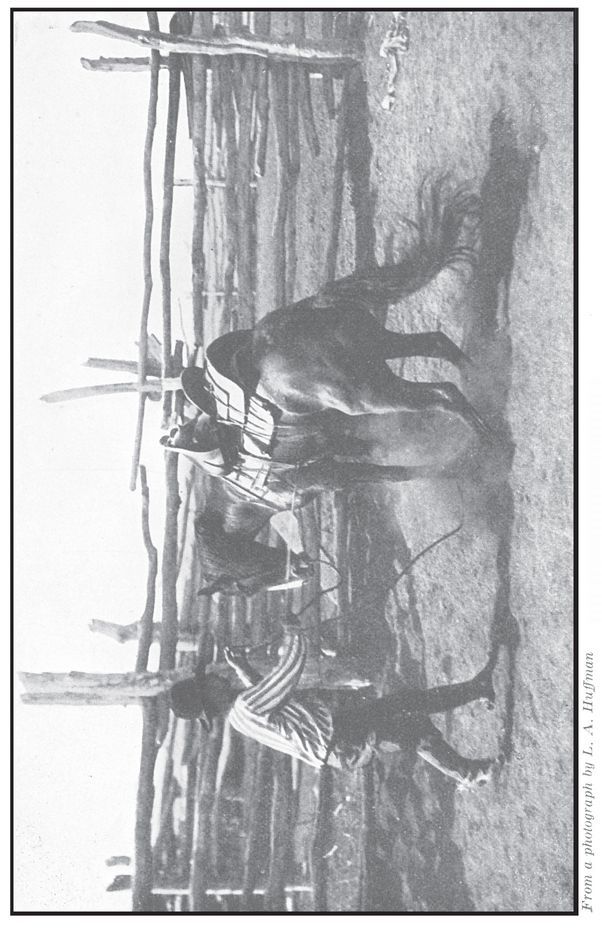

“CINCHING UP”

The saddle offered its occupant opportunity to sit in perfect balance, and such a seat was the one best suited to the type of horses and to the character of riding which were involved. The saddle’s occupant, because with body entirely relaxed and legs at full length and hanging flexed below him, was shifted from and had instantly to regain his equilibrium at every movement of his steed. The rider thus reverted to the primitive and subconscious balancing practised by the walker, the skater, and the bicycler, each of whom is ever righting a wrong position. The horseman with subconsciousness thus alert sensed through the stiffening muscles of his animal plan for untoward action, and thereby was forewarned of intended whirls, balks, or jumps.

At first sight, the horseman when at high speed appeared perhaps a bit grotesque, for his elbows were extended to either side, were held even with his shoulders and bobbed up and down, his hands were close together and before his chin, his legs hung loosely and straight downward, and his relaxed body, never rising from the saddle, swayed in seeming semidrunkenness. At second sight, the observer realized that all this mutualized the rider and his pony into rhythmic motion, and that the rider’s security of seat came from the synchronizing of man and beast.

This attention to the time beat was what insured the seat even during bucking, the spurs and buck hooks giving but incidental aid. It was what enabled the buckaroos in graceful swoops to lean from galloping horses and pick up objects from the ground. It was what permitted the acrobatic puncher to drop from a moving animal and mount another plunging past.

Finally, the stock-saddle was the almost universal pillow of the sleeping cowboy whether in the bunk house or afield.

It was on such a saddle that Leon, a Mexican, changing horses, traversed in 1876 one hundred miles in four hours, fifty-seven minutes; in 1877, five hundred and five miles in forty-nine hours, fifty-one and one-half minutes. It was on such a saddle, though one of light weight, that, in a still earlier year, F. X. Aubrey of the Pony Express rode across-country eight hundred miles in five days, thirteen hours.

Those homely-looking leathern structures helped to make the West, and should be regarded with affectionate respect.