CHAPTER X

THE DAY’S WORK

BEGINNING DAY’S WORK—MORNING SADDLING—OUTRIDING—BLABBING—ANIMALS’ AILMENTS—PORCUPINES—WAGONS AND JERK LINES—BULL WHIP—VARIOUS DEFINITIONS—SHOEING HORSES—CLOUD-BURST—INDIAN FIGHTING—MORE DEFINITIONS—PRAIRIE FIRES—THEIR CAUSE—CYCLONES—WINTER HARDSHIPS—FREEZE—WINTER GRAZING—DROWNINGS—WAGES—DRIFT—BOX CANYONS—STORMS—RIDING IN DIFFICULT COUNTRY—SELF-SUFFICIENCY OF BRONCOS—WOLFERS AND WOLVES.

THE next morning’s “sun up” brought every one, newcomer included, down to every-day work. This was usually of merely routine nature, but from time to time it swung suddenly into exciting channels.

The day’s business started early. With the first break of dawn, the crusty, ever-growling cook was out of his kitchen bunk, lit his fire, gave to the “horse wrangler” the unwelcome, conventional, morning salutation of “roll out,” and then set about preparing breakfast.

All during the night the riding ponies had grazed in close proximity to the house, had stamped about it, and occasionally had put their noses to its cracks, sniffingly to satisfy either curiosity or a desire for human companionship. Although the wrangler rose the moment he was called and limited his toilet to putting on his hat, the first wreath of blue smoke from the chimney already had warned the horses of impending work; and, by the time the wrangler got out of doors, not within half a mile was there a single steed save only the few dejected “night horses” inside of the corral. One of the latter was saddled, and the much scattered band of ponies was rounded-up, to trot with passive indignation into the fenced enclosure.

Breakfast did not long delay the men. In quick succession, the lesser eaters first in order, they carried their saddles and bridles to the corral, and in a trice had the animals equipped for service.

On cold days the more kindly riders held their bits a moment before the fire, and shielded them by a glove or a coat flap during the transit between the inner house and the horse’s mouth. They did this despite foreknowledge of their broncos’ prospective seeming lack of gratitude. Each of those exasperating little brutes would stand, head hanging meekly downward, and would resignedly permit the bridle to be put atop his crown, but the instant the bit approached his mouth this latter part of his anatomy in some mysterious way would be pointed almost directly upward and be projected from a semivertical neck.

After withstanding a slap or two and receiving many profane requests, the pony would lower his head to an easily reachable position; would release the vise-like set in which his closed jaw had been; would accept the bit and busily embark upon the champing of its roller; would fairly shove his forehead against his master’s hands that crumpled ears might be made more comfortable; would take the saddle; would gaze reproachfully at his tormenter; and then apparently would doze off.

Whoever was outside of the corral could by his hearing alone accurately follow the events within. Seeing was unnecessary.

At the house door a rider had paused and said: “I’ve warmed up this bit, acause I’m riding the finest little cow horse this State has ever seen. It sure has earned the right to decent treatment.”

Then the man had disappeared into the corral. There wafted out of it statements which, if carefully censored, would read as follows: “Good morning, Pete. Hope you’re well. Got a little piece of iron candy for you. Stop fooling, Pete. Stop your kidding. Stop that, I tell you. Pete, stop that. Stop it, I say. Look here, you dodgasted, pale pink, walleyed, glandered, spavined cayuse, pull down that injur rubber-neck of yourn, or I’ll skin you alive, and mash in your sides to hell and gone. Hold still, pony, and I’ll fix your ear. Is that comfortable? Now, Pete, here comes the saddle. Whoa, pony, stop twitching your fool back. Now, Pete, the front cinch’s fixed. All we’ve got left is the hind one. Pete, you dog-goned, inflated, lost soul, let out that wind and do it quick, or I’ll bust you wide open. Quit that, Pete. Quit it, I say. Good, old Pete, you sure are some horse.”

During warm weather life was comparatively easy. There were, of course, the spring and fall round-ups. The resultant “drives” to the “shipping point” at the railroad were made in autumn only, if the ranch were one for raising beef, or more frequently, possibly, than in both spring and autumn, if horses were the product.

There was the “gentling” of these horses. If the ranch were in a section that necessitated use of a different feeding-ground in winter from that of summer, the live stock would be shifted semiannually from one of these ranges to the other, the “winter range” being in the “low country,” while the “summer range” would be either upon the higher “benches,” or on the upper levels of the hills.

There were inspection trips about the Range, so-called “outridings,” to discover the location and physical state of the scattered groups of stock, to ascertain the condition of the water-supply and grass, to move the stock to fresh grounds if food or drink were found to be insufficient, to fend the animals away from known patches of loco-weed, to discover by “riding sign” whether any beasts were straying too far afield and if so to turn them homeward, to rescue through a tightly drawn lariat and straining pony some bogged or mired steer or horse and possibly receive reward in a charge by muddy, irate horns, to watch for signs of thieves, settlers, and predatory animals, and, if necessary, to lay traps or poisoned baits for wolves, and finally, on such ranches as “blabbed” their calves, to put “blabs” on the noses of whatever baby cattle deserved the unsightly little board.

Here and there about the Range would appear a lusty calf with an emaciated mother. If the calf were old enough, a thin board, six inches by eight in size, was, at the centre of one of its longer edges, clipped onto the infant’s nose. Thereafter he could perfectly well graze, but he assuredly was weaned. Blabbing was not always easy of accomplishment. The calf and his mater had to be chased so far apart as to permit the cowboy to rope and throw the calf, attach the blab, and remount his horse before there should arrive, head down and on the gallop, an irate and sharp-horned cow.

Diseased or injured animals were inspected, and, according to the nature of the disease or injury, were treated or destroyed. If disease required the animals’ isolation, the latter was effected through herding the animals by themselves under charge of a detachment of punchers; for, in the absence of gathered hay, imprisonment in foodless corrals was impracticable. No oversight was given to maternity cases, and births occurred wherever upon the Range the mother happened to be.

The Northwest harbored one particular ailment concerning which many tenderfoots, and even many of the ignorant farmers, had extraordinary misinformation. In terrifically cold weather, cattle’s hoofs and horns sometimes would freeze, and thereafter the horns, on thawing, would in some instances fall off. The discarded horns, of course, were hollow, as were the horns of all cattle; but ignorant finders of the castaways created in good faith the disease of “Hollow Horn,” and deluged governmental officers with requests for curative prescriptions.

In addition to all these incidents of “outriding,” there might be the work of salvage at some cloudburst’s scene, a prairie-fire to suppress, an urgent call for aid against marauding Indians, or the start for a drive either on the Texas Trail or from, say, Oregon to Wyoming.

Perhaps, also, there arrived a puncher testy from the import of his message: “A couple of you come up with me to Indian Creek. The porcupines have gotten in there, and ten of our best mares have kicked themselves plumb full of quills.” This meant for the unfortunate horses no danger, but considerable discomfort. One by one they would be thrown and triced fore and aft by lariats, while a very irate gentleman squatted at their heels, plied pincers on the offending quills and volubly cursed all the members of the Rodent family from the original immigrants down to the then present generation.

Zoologists possibly know whether or not the porcupine had functions in addition to the three he exhibited to the cowboy. These were eating latigos and saddles, decorating horses’ hock joints, and using Towser’s inquisitive nose for a pincushion.

Mail had to be carried to and from the post-office, perhaps a hundred miles or more away; and yearly the wagons had to make a long trip for supplies.

These wagons, stout, springless, creaking things, traversing unconscionable roads and country devoid of road, taking to the boulderstrewn beds of streams when the map turned on edge, were dragged on their bumping, noisy way by two or more spans, all driven by a man seated upon the wagon’s front and handling ordinary reins.

Or else the wagons were drawn by a “jerk-line string,” a string of horses or mules harnessed either in single file or in a series of spans, and, in either case, following a highly trained leader controlled by a “jerk line.” This jerk line, a single, continuous rein, starting from its fastening at the top of the brake handle, extended to and through the hand of the driver, who either was astride the wheel horse (the near one, if two) or was seated on the wagon’s front. The line continued thence along the long file of horses’ backs and to the left side of the “lead animal’s” bit, this without touching the bit of any intermediate brute. A single, steady pull on the line guided this lead animal to the left. Two or more short jerks turned it to the right. Constant and loudly voiced reiterations of the old, oxen-driving commands of “gee” and “haw” directed the intervening beasts; and also, with the leading one, supplemented the effect of the jerk line.

Profanity and a whip did the rest; did it easily unless the wagon outran its brake, and sliding onto the heels of its motive beasts caused them to “jack-knife,” which is to say, to turn backward at an acute angle. In such event, profanity outdid itself.

Commonly, with animals in a series of spans, the left-hand beast in the front span was the only “lead” animal, and thus alone had the honor of holding the jerk line. In such case, he and his span-mate would have their bits connected by a short strap, thus causing the span-mate to be towed to the left when he was not either walking peacefully forward or, by his companion, being violently pushed to the right. But, if this span-mate were qualified to share in the leadership, the jerk line, toward its far, outer end, would, for a way, be split lengthwise, one branch so produced being attached to the bit of the left-hand lead beast, the other branch being fastened to the bit of the span-mate, in each case to the bit’s left side.

The driver of any “string team,” whether it were single or double, might operate it unassisted, or there might be upon the wagon an aide who was termed a “lasher,” and whose task was to swing the whip, to push upon the brake-handle as the driver, with his jerk line, pulled it forward, and finally to co-operate in the swearing.

The whip mentioned above either was a wooden stock four feet or so in length and with a long, slender lash attached, or else was in the form of the now historic “bull whip.” This latter instrument was a short stock which carried fifteen to twenty-five feet of plaited, rawhide lash. This lash was quite thick near the stock and, weighted there with lead, tapered to a point, and so continued into a buckskin “popper” three feet long. It could, at the wielder’s choice, land anywhere, silently or with a pistol crack, and this with either the gentleness of a falling leaf or force sufficient to remove four square inches of equine skin.

Often on steep “side hills,” cowboys, riding above the wagon, fastening their lariats to the top of its load, and having their ponies pull back with all their might were all that prevented an overturn or a slip to the bottom of the declivity. Upgrades frequently were negotiable only because these cowboys, with lariats taut between wagon and saddle horns, rode beside the vehicle, their ponies “scratching gravel,” hauling with prodigious enthusiasm, and giving welcome aid to the “work horses” straining in the harness.

The tractive power in the combination of a man, a horse, a lariat, and a stock-saddle was at first sight astonishing. The logs for many a ranch building thus were “snaked” from the forest to the house site. It was the ordinary way of transporting wood to the camp-fire.

Frequently, when descending a sharp declivity, the wagon was held in check by ropes tied to the rear axle, twined about convenient trees, rocks, or saddle horns, and slowly paid out.

The wagons were driven by “teamsters,” not by cowboys. The latter essayed few tasks that could not be accomplished from a bronco’s back. The punchers described themselves as being “too proud to cut hay and not wild enough to eat it.” The puncher was so wedded to horseback that, when he took to a wheeled vehicle, if only as an extra passenger, he, as he said, “rode the wagon,” and did not ride “on” or “in” it. Of course, a teamster might once have been a cowboy, but no one “teamed” or “threw the bull” so long as he still could sit the buck.

Did the teamster quit his ranching life and drive a freight-wagon on some regular transportation route, he thereby ceased to be a teamster and became a “freighter,” this last term having been until well into the decade of the seventies interchangeable with “a professional.” While still called a freighter, he might coincidentally be termed also either a “skinner” or “mule skinner,” or else a “bull whacker,” according as his tractive animals were mules or, as far more often in the earlier years than in the later, yokes of oxen; and if his outfit were a jerk-line one, he was apt to be termed exclusively a skinner. In Range English, one did not “drive” a jerk-line string, but instead “skinned” it.

Teamsters used all the cowboys’ profanity, and in addition had “private cuss-words” of their own. Their “chariots,” “sulkies,” “barouches,” “gigs,” “buggies,” or whatever else they chose to term their heavy wains, fairly reeked with blasphemy. Thus a “wagon outfit” was no silent cortege.

The teamsters, while on their trips, were apt toward evening to receive much flattery from attendant ranchmen. The reason for this was that each teamster had entire jurisdiction over the “sheet” of his wagon, and this canvas cover when laid upon the ground made a warm and wind-proof bed for several men. Throughout the Range, any custodian of a “tarpoleon” or “tarp,” as the West termed all canvases not specifically entitled as either “pack covers” or “wagon sheets,” was very popular after nightfall.

The paucity of bridges and the absence of decent roads imposed upon the teamsters in rainy weather many a halt, some of them each of several days’ duration. Such compulsory stoppings were termed “lay ups,” while voluntary delays, particularly in towns or at ranches, were called “lay overs.”

The country might be too rough to permit the wagons to reach far-outlying stations, and for such places the “pack-train” of bundlecarrying horses was the only transporter of food.

But the list of daily chores is not finished. Horses had to be shod, work animals on all four feet, saddle animals, if at all, on the front feet only unless the beasts were to be used in very rocky country. In this latter event, they were usually shod “all round,” i. e., on each of their four feet.

Repairs had to be made to saddles and to wagons. Lariats and harnesses had to be mended.

In the shoeing of horses, the shoes employed were everywhere ordinary metal ones, except that in the far Southwest occasionally an Apache Indian habit was adopted, and green rawhide was wrapped about the hoofs, there to dry and become almost as hard as iron.

The shoeing of the average Range horse was disturbing to human tranquillity. The shoeing of some horses was a miracle or a devilment according as one viewed it. Bill Evans one morning said: “I’ll shoe that pinto cayuse right arter breakfast, and I reckon I’d better pin shoes onto all his feet. Joe, you come down and help.” Presently, from the corral rose snorts and the sounds of scuffling, the strident voice of Bill and the bellowing tones of Joe, all merged into a single hymn of trouble. One of the ranch owners, sauntering over that way, found an angry pony glaring at two perspiring men, and asked: “Shod him?” He was answered by Bill: “Guess so. Tacked iron onto everything that flew past. It sure is a heaven-sent mercy that broncs ain’t centipedes.”

The cloudburst, when it came, produced a real task.

There had been a long period of rainless weather; and panting cattle, for mile after mile along the almost dried-up bed of a highbanked, meandering stream, were drinking at the isolated, surviving pools. Black clouds gathered. They coalesced. Then lightning split the sky; and, between the sky and ground, the down-pouring water was so dense as to make breathing difficult. All of the deluge that fell upon the prairie, baked as it was like a tile, rivuletted into the main stream. In too few minutes for the cattle’s realization they were in danger; and, merely seconds after that, they were the playthings of a brown, swirling flood.

At some sand-bar or sharp angle, the floating cattle jammed. Into that mess, which was here writhing, moaning, wounded, here struggling but unharmed, there motionless and dead, cowboys delved with lariats and tugging ponies.

Shots ended suffering. The next chapter was skinning of carcasses and drying of hides.

A clash with Indians was often no mean affair. After the government had forced the Indians onto reservations and thus had left the bulk of the plains to the ranchers, an Indian tribe occasionally “jumped” its reservation, and in a carefully planned “uprising” or “outbreak” went upon the war-path. Cowboys would be drawn into this so-called war, either through running foul of the belligerent Red Skins or being taken on by the army for auxiliary service.

But there was another and lesser form of Indian disturbance which was more frequent, and with which the puncher had more proximate connection. From time to time numbers of the Red Men in entire peacefulness and, either pursuant to shooting permits or in childlike defiance of regulations, wandered beyond their reservation’s limits. With the unreasoning inability of the Indians to resist their desires, attractive horses were presently “rustled” and driven away, while fat cattle were killed and eaten.

A cowboy came onto the scene and attempted to save the white owner’s property. Shots eventually were fired. News of the affair flashed through mysterious Indian channels back to the reservation, and out poured its more militant inmates. News of this leave-taking sped up the Range, carried by a galloping horseman and by three shots from a rifle. The ultimately concentrated cowboys advanced upon a group of the still bewildered and indecisive Indians; and, answering a single shot by a scattering volley, blew away all indecision and started an active fighting.

The soldiers arrived later, and brought to an end hostilities that never would have commenced had the military uniform appeared on the scene before the cowboy did. Once the soldiers arrived, the punchers present might be asked to assist as packers or guides; but often and because of their notorious lack of interracial diplomacy they were urged in the most forcible language known by the army to withdraw from the neighborhood. The directness and promptness of punchers’ methods did not accord with Indian mentality, and to the cowboys’ honest but ill-advised action in affairs of this sort must be laid many a subsequent, serious uprising by the Red Man.

The term “rustle” employed above had curious and inconsistent usage in that, when applied to live stock, it almost always implied stealing; but when relating to anything other than live stock it, with almost equal regularity, denoted a legitimate getting.

The much-used term “outfit” had similarly diversified meanings; and variously signified, according to its context, the combined people engaged in any one enterprise or living in any one establishment, a party of people travelling together, or the physical belongings of any person or group of persons.

The prairie-fire sometimes produced exciting duties. Fires were frequent; but usually were of small importance, and, if promptly attacked, easily exterminated. At other times, however, they were terrifying.

For successive weeks an arid heat and a lifeless air, at ten o’clock acrid whiffs and a blurred horizon, but at twelve o’clock a biting smell and the horizon gone. Out there, somewhere, was a line of grimy men desperately fighting to stop the march of the advancing flames that the latter might burn themselves out upon their self-selected battleground. Punchers with eyebrows and eyelashes gone, with wet handkerchiefs over mouth and nose, in mad haste but with cool reasoning, “straddled” the fire; two mounted men, one on either side of the flames, dragging behind them at their lariats’ ends a green hide or wet blanket. Other men either mounted or afoot, scarred and intrepid like their brothers, beat upon the fire’s side-lines with similar utensils or with bunches of brush.

The thickness of the grass or the velocity of the wind might generate heat or movement such as to make straddling unfeasible, and then the only remedy was to “backfire” across the enemy’s prospective line of march. Along the zone selected for the “back-fire,” a horseman trailed a bundle of burning fagots. The flames thus started were held in check on their homeward side by straddling them.

In the early stages of the contest, living warnings intermittently came out of the wall of smoke, for an occasional deer or antelope, a solitary horse or steer would rush, wild-eyed, past the toiling men. Thus the best experts on the subject of danger had advised human retreat, but such retreat was not to be considered.

The last of these fleeing animals had passed through the line of fire fighters. There was a sudden puff far in the rear, and in an instant the prairie behind the men was ablaze. It was mount and reach the shelter given by a projecting hill, by the bottom of a coulée, by a grassless, “buffalo wallow,” or, in the language of the craft, it would be “fried gent,” “no breakfast forever,” and the “long trail to Kingdom Come.”

With safety thus attained, the next and an immediate task was to gallop down to leeward, again to move out before the flames, and to re-engage the enemy upon the same tactics as before.

There was peril in the extensive fires, for they would sulk and make slow progress for a time, and then would leap forward in irregular frontage more rapidly than a horse could run. They, on occasion, would travel for many miles. The peril was particularly for such as had to fight the flames and so, having to stand their ground, could not materially shift position. But any one who merely sought escape would find that, through the average fire, ran here and there safe lanes made up of interrupted and quite dissimilar elements, a stream’s bed, a rocky ledge, a bit of grassless earth.

Of these fires, some were caused by lightning or by sparks from locomotives, others had broken away from farmers who had planned a merely local burning in order to fertilize their lands or to rid the latter of annoying weeds, others had escaped beyond the tract in which cattlemen either were eliminating loco plants, or else, warring against sheep, had deliberately kindled flames for the purpose of “cooking mutton.” Still others came from the carelessness of campers or of smokers, while, in the earlier years, still others represented Indians’ attempts to drive game animals into strategic territory.

Within a forest floored deeply with pine-needles, one tiny ember from a negligently abandoned camp has more than once been the parent of a subsurface, incandescent mass, which days later has a quarter of a mile away gnawed out a breathing hole, and, tasting air, leaped into a holocaust.

For a while after the advent of the early farmers, the latter were employed to “run fire guards” yearly here and there in certain sections of the Range, that is, to plough two parallel sets of furrows, which were some fifty yards apart and had four furrows in each set. The grass between the sets was then purposely burned by men who were trailed by water-laden wagons.

At rare intervals, a cyclone whirled its way across the flat lands, leaving in its trail dead animals, and on either side of this trail living, crazed brutes still galloping in wild stampede. When such a tempest broke on a driven band, “hell was a-popping and a-popping hard” for the herding cowboys. Wind, thunder, and lightning in wholesale quantities brought out the hardest sort of riding before the survivors from the punchers’ maddened wards could be headed back into orderly formation.

The cyclone’s prelude was awesome. Its arrival was terrific. A sky of inky blackness suddenly in one quarter suffused with tones of copper and dark green. Whatever wind had been blowing ceased, and there fell a silence, death-like save for the nervous lowing of the cattle and the subdued conferring of the men. Presently from the sky came a long-drawn moan; and next, with a roar, a screwing, lightning-capped funnel, point down, lined with dust, bushes, and trees, rushed out of the copper and green, and tore across “the flat.”

The punchers, with but seconds in which to act, strove to guess the funnel’s prospective course and to throw the cattle from it and, if possible, into protecting gullies. Despite the limited time, there was some opportunity for manœuvring, because the funnel was usually of comparatively small diameter, a few hundred yards at the most. Moreover, it occasionally would “hang,” which is to say, would, for a moment or two, slow or even halt its forward progress, though still maintaining its dervish whirl. Then, too, the awful contrivance might have the decency now and then to “skip,” “lift,” or “raise,” that is, for a while to retract its tip from contact with the earth, and thus to sail along harmlessly until the tip again dabbed down to earth and resumed its murdering.

The funnel, as though repentant of all this generosity, would on occasion make frequent and erratic changes in its course, and stab in unexpected places.

The hurrying punchers clung to the fleeing cattle until the last possible instant, then spun their horses into facing the storm, leaned flat upon their animals’ necks and, at topmost speed, smashed headlong through the thin but seemingly solid wall of wind that flanked the cyclone’s funnel upon its right and left. It was not a comfortable impact. It savored of colliding with a pile of bricks.

Taken sideways by the wall of wind might mean a horse blown over. Taken in any position by the funnel almost surely meant death.

Reputable witnesses have in seriousness reported cattle and horses as picked up and carried more than a quarter of a mile through the air before nature tired of her playthings and dropped them.

Other men, equally reputable, have with less seriousness given other details. Johnny Nealan, a much-respected rancher of Oregon’s John Day country, recounted that he, when lifted from the ground by the wind, had in his hand a twenty-dollar gold coin, but that, before he returned to the earth, the money had been blown into two fifty-cent-pieces and one plugged nickel.

Snuffles Jones solemnly averred that a certain Kansan tornado had swept all the earth away from around the badger holes, and left these holes sticking up into the air. Asked how he could have seen them, he retorted: “Didn’t see ’em. Ran into ’em.”

However, the cyclone had unpleasant elements in addition to that of wind.

Vivid lightning, tossing itself about with constant flash, and just above a treeless plain, was in no way soporific to rain-soaked men astride of rain-soaked horses.

After each particularly blinding streak and the crash of its thunder, at least one dripping puncher saucily would implore nature to “raise your sights, raise ’em a lot,” and thereby far to overshoot him. Though not affirmatively afraid, the puncher sometimes had a sneaking suspicion that his invocation might not be heeded, because, as a rider from Billings, Montana, once observed: “Nature is a skittish beast and no ways bridlewise.” Occasionally, to sustain good-nature amid a huddled, physically uncomfortable group of men, one of the group would resort to blithesome foolishness. Thus the rigmarole “She loves me, she loves me not” was in more than one instance used to count off recurrent streaks of awesome lightning, just as that same rigmarole, at another time, followed the drone and spang of Indian bullets which were arriving successively and with unpleasant neighborliness.

On still another occasion three ambushed punchers took to cover. Their range presently was found, and dust began to spurt around them. The bullets, coming with the crescendo, acid whine that sometimes they affect, produced no comment beyond “Merskeeters is gettin’ thick.”

Winter brought hard work upon cold ranges. Though the tasks were few in kind, they were strenuous in performance. Inspection trips with the thermometer at forty degrees below zero, night-herding under like conditions were not amusing, but the stock had to be guarded, however loosely, night and day.

Upon a large ranch the work was performed in part by punchers operating from the main buildings, in part by punchers who, stationed in far-off outpost cabins, so-called “line camps,” patrolled as “line riders” prescribed boundaries. These men were interchangeably called “line riders” or “outriders,” though, strictly speaking, a “line rider” had a regular beat, while an “outrider” was commissioned to roam anywhere.

Effort was made to minimize the duration of continuous work, and the men served, so far as possible, in shifts each of twelve hours. But the West stuck to its job until the latter was done, and never quit at any mere clock strike, as do adherents of the modern eight-hour principle.

The riders had always to know where grass was plentiful and the snow above it reasonably shallow, and constantly to keep their wards shepherded within such happy territory, for the animals’ only food was the grass, and they could reach it solely by pawing through the snow. Horses could obtain their provender through even four feet of covering, if the latter were powdery; but let an ice crust form, and the story would be very different. A thaw, immediately followed by a freeze, spelled disaster on the Range.

Even in snowless stretches danger lurked, for rain, promptly succeeded by tremendous drop in temperature, turned each grass blade into an icicle so armored that the live stock could not eat it.

The winds however cold were friendly to the stock in that they swept away the snow from wide stretches of grazing-ground.

In the Far Northwest blew a specially amiable wind, the Chinook, born above the warm current of the Pacific Ocean, and intermittently coming to save the Range in its hour of peril. In the early morning one saw the mountains dazzlingly white, the lowlands spread with snow; then came advance couriers in little puffs of air, and next the wind itself. The stout air-current wiped the white from the hillsides as a handkerchief clears a perspiring forehead, and freed the plains from their murderous covering. The transaction was so rapid that the snow did not seem to melt. One moment it was visible, the next it had gone.

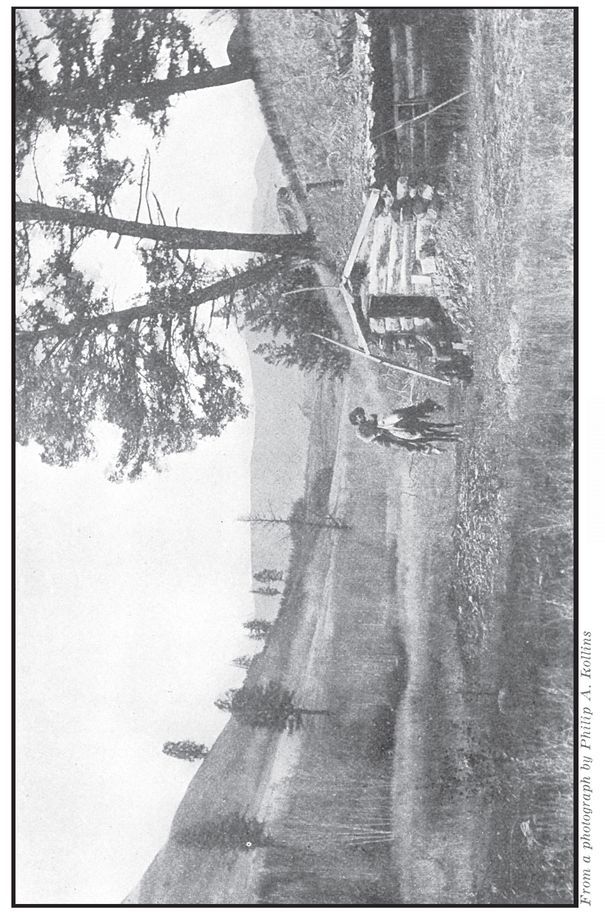

A LINE CAMP

Although during the winter the horse herd pretty well could take charge of itself and needed little guidance, the cattle throughout that period were a constant care.

When snow fell the cattle frequently lacked initiative to search for food. Bothered by the wind, they at times left the hillsides, where the grass was within pawing reach, and sifted to the valleys’ bottoms, where the drift-covered forage would have been insufficient for the many brutes even if they could have reached it.

One of them, becoming thirsty, started for a hole in the ice formed upon the waters of a lake. The other animals mechanically followed. Ton after ton of weight stupidly, uselessly moved out from solid shore and the inevitable happened—loud, cracking sounds, wild bellowings, tumultuous splashings, and then new ice, marred here and there by a projecting horn or tail.

Upon sign of an impending storm, were it day or were it night, off went the riders to hustle their charges behind the protection of trees or projecting rocks, or else into valleys or swales, which, at right-angles to the blast’s promised track, were less likely to be buried deep in snow and, above all, to keep the stock from “drifting.”

Throughout the winter, numbed, ice-clad men sat night and day atop exhausted horses, fighting the tempest, were it Texan “norther,” or Northern “blizzard,” that “away back East” might eat roast-beef and ride in street-cars. For such a life the maximum monthly wage in the decade of the eighties was for a first-class or “top” rider forty dollars, with ten to forty dollars additional if he were a competent ranch foreman; for a rider of less than top rating twenty-five dollars and upward; in each case with board and lodging free. Of course, there were exceptions, and some of the large ranches paid monthly as much as two hundred dollars to an able foreman.

The “drift” was often tragic for both the animals and their owners. It might send to death practically all the cattle of a range. Cattle were its usual prey, for horses almost always had sense sufficient to avoid it, and to find shelter for themselves.

The drift was the live stock’s marching in wholesale numbers away from a particular locality, either to avoid the local conditions or to seek better conditions elsewhere. Deep snows having covered the grasses, the discouraged cattle would assemble just as they did for the already described, unintentional drownings in a lake, would suddenly in compact formation begin their trek toward their self-selected, unknown land of promise.

Were the weather not stormy, the beasts would march along for miles and until stopped by some insurmountable obstacle, all the way unwittingly bettering themselves by ploughing a wide cut through the snows. Stopped by the obstacle, whatever it was—a hill, a canyon, or aught else—the beasts would about face, and, retracing their former trail, would browse their way along its partly cleared bottom and back to their starting-point.

But stormy weather might produce a very different result. A bunch of cattle were pawing through the snow and eating their hard-earned ration, when a storm broke upon them. As the air became filled with blinding flakes and the killing wind increased, the beasts uneasily stirred about, then, seeking protection, huddled themselves into a compact mass. With the water from their eyes freezing, with long icicles hanging from their lips, with their backs rime-coated, they stood, head down, moaning, hopeless. Abruptly, in sodden despair, with brain entirely dormant but muscles automatically working, some forceful steer started down to leeward, and behind him, in like condition, straggled the staggering herd. Each animal, keeping true to the wind’s course, fought on till the animal dropped; and where it dropped it died.

The numbed brutes fell one by one, first the weaker calves, then the stronger calves, each little tumbling body causing its attendant, anxious mother to stop and wait and perish beside a diminutive mound of snow. Next toppled the weaker steers, then the more virile animals, until the final sacrifice appeared in the frozen bodies of some grand bovine monsters, lying piled before the impassable barrier of a high snow-drift, a deep cut, or a rocky wall.

Material was plentiful for the skinning knives and for the birds and beasts of prey.

Could mounted cowboys, like a flying wedge, have plunged their horses into the mass before the leading steer began the hypnotic march to death, the herd might have been driven to safe cover; but, once the fatal procession started, the doomed animals would obey no order except the summons to destruction and, in the frenzy of hopelessness, would savagely attack whoever sought to rescue them. “Might have been driven to safe cover,” but not assuredly. Many a puncher has galloped into a “drift,” and, exhausted by his futile efforts, perished with the beasts he tried to save.

A “drift” might occur in summer weather and be the aftermath of a stampede or the result of drought-made scantiness in local drink or herbage, but such a drift would mean no more than that a group of cattle had wandered far afield. It had no terrors.

In snowy weather the punchers had also to keep the stupid cattle from self-immurement in “box canyons,” which were gorges with but a single open end, the inner terminal being against a wall of rock within the mountain’s mass. A high snow-pile across the entrance might insure starvation for all hoofed beasts within the prison.

Even when unhampered by any responsibility, mere facing of the blizzard offered sometimes to the cowboy a very material hazard. More than one man, leaving his door for the purpose of obtaining wood from a pile fifty feet away, has been so confused and blinded by the shrieking wind and the hissing, stinging snow as to lose all sense of direction, and, devitalized by aimless, unsuccessful searches for some familiar object, has wandered down to leeward, the course instinctively adopted by all storm-numbed wayfarers when headed for the grave. To leeward was whither rescue parties first gave attention in their sad search across a waste of snow.

In particularly storm-swept areas, occasional prudent men, before plunging from their house-doors into the flake-filled air, tied one end of a rope to the door-jamb, and, as they went forth, held grimly onto the other end of that bit of saving hemp.

In the open stretches of the colder sections of the country, there would form crust, often strong enough to support a bronco, sometimes even a wagon with its draft teams. Over such a surface ponies with sharpened shoe calks could be ridden with impunity; but, under average wintry conditions, the local riders were compelled to do considerable navigating in order to avoid soft drifts and deceptive, snowfilled hollows.

At times horses were useless, and for locomotion the men were restricted to the ski. This form of snow-shoe was carried into the West by the Scandinavian linemen whom the telegraph companies employed.

While at times horses were useless, such times were few, for, broadly speaking, the bronco could go anywhere that a man could, save only where the latter in climbing was forced to use his hands, and save only where bog covering or ice too frail for the horse’s weight would yet support the lighter human being. Up or down dizzy, trailless heights, over rocks or snow, the wiry, sure-footed cayuse would pick its way and carry its rider, occasionally pausing at some turn to gaze with nonchalant curiosity into the valley a thousand foot almost vertically below.

When descending particularly steep and dangerous slopes, some animals sat on their haunches, and, stiff-kneed, using their front feet as both rudders and brakes, contortingly slid themselves along. To a tenderfoot such an approach to a canyon’s rim was decidedly nerve-racking.

Upon ascents however steep, the cowboy usually remained in the saddle and, leaning far forward over the neck of his horse, aided the enterprise by a series of violent forward swings, each in time with one of the horse’s upward lunges.

Nevertheless, upon long up grades over shifting gravel or soft snow, the puncher might dismount, and, by seizing the end of his animal’s tail, obtain a powerful tow-line. Prudent users of this tractive method cast loose just before the steed passed over the summit, for a horizontal bronco and a human head on a level with the beast’s heels might prove an irresistible combination. On the up-hill journey the towed puncher was free from danger, since he was below his beast’s kicking plane.

An open winter made life physically comfortable; but it caused worry about prospective drought, because summer’s waters came largely from the melting of the previous winter’s snows.

The subject of ice and snow suggests what has amazed many an Easterner, the bronco’s ability safely to drink the coldest water. A ridden horse in a lather of sweat would fairly fill himself at a semifrozen stream, and afterward happily go on about his business. He never had lived indoors, never had been blanketed, and so he had no fear of being foundered or of catching cold from drafts of air.

Incidentally, he never had been groomed by any man. Whatever person had touched a bronco with currycomb and brush would have had immediate use for a tombstone.

The Western horse groomed himself. He would roll in the dust and the bunch-grass, would shake himself, and, if in good physical condition, would thereafter shine as though hostlers had rubbed and waxed him.

This lack of acquaintance with currycombs was no more marked than was the absence of all familiarity with oats. Many a pilgrim, at the outset of his initial Western visit and with best of intentions, has poured oats onto a bit of canvas, and has led his pony up to what humanly was planned to be an equine feast. A few suspicious glances would be followed by an inquisitive sniff or two, by an inhalation that drew some prickly oat-grains up the pony’s nose, by a strenuous and disgusted snort, and by a shower of oats. The cynical little cow-horse, knowing whence his saddle came, had small confidence in anything else man offered him.

There has been mentioned, as being one of the puncher’s functions, the laying of poisoned baits for wolves. The cowboy was relied upon for this service only when the animals were not uncomfortably numerous; as soon as in any locality they materially increased in number, and their toll of murdered calves and colts became unduly large, there was temporarily hired a “wolfer.” He was a professional killer of wolves; was a man usually very “sot” in his ways, and who, by instinct or training, could outwit the “varmints” and cause them to walk into traps or to eat mortiferous meats when none of the ranch staff could entice them to do more than emit derisive howls. The wolfer had the uncanny habit of stuffing his loose tobacco and cigarette papers into the very pocket that contained a pound of unwrapped strychnine crystals, of smoking all day long, and of being well at supper-time.

Some ranches maintained packs of dogs for the purpose of wolfing; though the majority of cattlemen, doubting the hounds’ willingness to spare the live stock’s young when the wild animal was absent, and also realizing that, should the dogs, unattended, wander from home the brutes might be shot, preferred wolves to a Range war, and accordingly forewent canine protection.

The wolves throughout the Range did not begin wholesale eating of calves and colts until after the buffalo with its calf had passed into history, or, more definitely speaking, into sleigh-robes and fur coats, and into the stomachs of the men who built the Union Pacific and Northern Pacific railways.

The Western railroads, through their cattle trains, enabled ranching to become a national industry; thereafter, through their eating buffalo, unloosed the wolves against the commercial live stock; and finally, through their wheat cars, took the farmer westward and enabled him to slay the Range.

The wolves fell into two classes, one, a small animal, the coyote or cayote, popularly known as “kiote,” the other a large beast which, without regard to possible scientific subdivision, interchangeably was called “timber-wolf,” “gray wolf,” “big gray,” “buffalo wolf,” “traveller,” “loper,” “loafer,” “lofer,” “lobo,” or else “wolf,” with any one of the last-mentioned five words as a prefix, as, for instance, “lobo wolf.”

The lobos were often very hard to capture; particularly when in rare instances they added to their own extraordinary sagacity the cunning of a pair of coyotes which had attached themselves to the great wolf’s presence, and, as sycophantic pages in waiting, accompanied him on all his travels, and scouted one on either side of him.