4

Reading with Women

Reading when I can be indulged in it, is the elysium of my present life.

THOMAS JEFFERSON TO

FRANÇOIS ADRIAN VAN DER KEMP,

FEBRUARY 9, 1818

Where would nineteenth-century literature be without death, foreshadowed by sensational distress and heart-arresting anguish? A minor novel of 1826,

Yorktown: An Historical Romance, takes its patriotic theme, the decisive battle in securing U.S. independence, and inserts into the contest a wild-eyed, cross-dressing Continental soldier named Maude. She is all the more desperate because she is a fallen woman who abandons her prescribed gender role. In battle, Maude is stabbed by the same man who stole her innocence, a conniving loyalist commander, and she lives just long enough to learn of the American victory. Yet it is not the villain’s sword that kills her. Out of control emotions finally lead Maude to take an overdose of the opiate laudanum. Her death is a reminder that a woman who fails to heed society’s principal warning to her sex can never be reestablished. In the literature of Jefferson’s late years, suicide was generally the only way out for a woman who did not qualify for a life of quiet domesticity.

1

Thomas Jefferson espoused liberal sentiments that have been the cause of frequent celebratory speech among modern humanists: He defended the rights of ordinary citizens against the disproportionate exercise of power by society’s rich and powerful; he believed in extending education to all so as to rouse the general public and stimulate democracy. But he stood in the way of women’s rise; he refused to link intellectual capacity to public visibility; he wanted women protected from all coarseness and competition. He could not imagine female talent in the marketplace, or in government.

It could have been otherwise. The intellectual resilience of Abigail Adams is perhaps too prominent an example, and she, seemingly, so confident a thinker that she cannot serve as a singular contrast to Jefferson’s sense of the ideal feminine style. But his controversial vice president, Aaron Burr, loved and wed Theodosia Prevost because of her discernment, sturdy wit, and public versatility and fearlessness; she was several years older than he. Previously married to a British officer, who died overseas in the midst of the Revolutionary War, she succeeded, through her unabashed politicking ability, in maintaining good relations with prominent patriots—the respectable equivalent of the fictional Maude’s story. The Burrs’ subsequent correspondence contains a literary showiness that reveals both playfulness and his respect for the subtle turns of Theodosia’s mind. After his wife’s untimely death, Burr raised his daughter (named after her mother) to be similarly adept and unafraid, a woman who enjoyed the writings of the English feminist Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797). Dolley Madison, who appears to have been introduced to James Madison by Aaron Burr, is another who impressed men by her knowledge of the conduct of politics, no less than by her refined and reassuring manner.

2Jefferson, on the other hand, held fast to rather conventional notions of a woman’s role at home and in society. In spite of the obvious talents of his own daughter and granddaughters, he subscribed to the medical opinion that men were naturally more firm and made to exercise their reason, women more supple and made to emote—and that sex roles were immutable. He thought that a healthy republic was one in which every inherently passionate female was transformed into a dutiful wife and nurturing mother. He feared the tensions and what he imagined would be anarchic results if well-bred women were too exposed, that is, if they should enter the naturally bold and aggressive man’s world (constituting “promiscuous assemblies,” in the language of the time). He wrote with foreboding to his secretary of the treasury, Albert Gallatin, in 1807: “The appointment of a woman to office is an innovation for which the public is not prepared, nor am I.”

3It would seem from this that Jefferson was simply afraid of a society in which women actively went about acquiring the tools to compete with men. But nothing is ever so simple. He was not prescribing cultural uniformity. He did not revolt, as much as the Adamses did, upon witnessing how brazen French women could be. His granddaughter Ellen remarked that his expectations from the female intellect were great: “I have known him to lay down for a young lady a course of reading which might have startled a University student.”

4 In later years, Ellen expressed her own faith in the abilities of women. When she visited London and saw young Queen Victoria riding in an open carriage, she wrote in her diary that “it is surprising what a feeling of

loyalty women of all nations seem to have towards this sovereign of their own sex.” She then added: “We are so seldom called to fill high places that our hearts are stirred at once with pride & love when we see the destinies of a great people even nominally committed to hands like our own.”

5 Ellen had learned in her grandfather’s house to set her sights high, but also to accept variations among the women of the world without rejecting the healthfulness of the model that he had imagined right (or felicitous) for his own immediate surroundings.

Demonstrating the range of acceptable thinking on this subject, Dr. Benjamin Rush wrote conventionally to a young woman about to be wed: “From the day you marry you must have no will of your own. The subordination of your sex to ours is enforced by nature, by reason, and by revelation.” Yet the same Dr. Rush had published a few years earlier his

Thoughts upon Female Education, a work proposing that young women should be liberated intellectually, and, as citizens, fully encouraged to pass judgment on the subject of politics. The ambitious

Thoughts would be reprinted many times.

6As a medical school lecturer, Dr. Rush based his teaching on the belief that the nerves of women were “more susceptible of impressions of mind and body” than those of men, thus “more subject to nervous diseases.” If their natural softness made them neurologically fragile, it also extended their lives (explaining why there were more aged women than aged men). Thus destined to live alone for more years, and “precluded by custom, or perhaps nature [!], from making a choice in matrimony,” women were possessed of “more acute” moral faculties and “fitted for their solitary situation by a more exquisite s

ense of Deity.” Naturally devout, women were endowed with more “fortitude,” if less “courage”—though the latter “attaches no dishonor to their characters, as it does to those of men.”

7Gender considerations were political, whether or not publicly expressed as such. Believing as Rush did that a woman’s chief influence ought to be by way of love, natural perceptiveness, and superior taste, rather than through direct argument, Jefferson, reared among the colonial gentry, found it culturally near impossible to speak or write to a woman in the same way that he spoke or wrote to a man. Though his literary persona exhibited the softened disposition of an eighteenth-century Man of Feeling, and almost transcendently sympathetic when he wanted to be, Jefferson knew the difference between the “male” and “female” forms of “prudence”: One was clearly proactive, the other passive. He would not have described his manner as “feminine” in the way certain (friendly as well as unfriendly) commentators did, because his effort to balance sincere masculine sentiment with reliable masculine prudence or rationality was a well-developed matter of style, the manner of a bookish man, and a means of putting people at ease, rather than unconscious behavior one might superficially situate on a spectrum of femininity/masculinity.

The community of men to which Jefferson belonged used a particular vocabulary to secure reputations for decorum and propriety. In being taught to exercise “prudence,” they were also taught to shun its opposites: “extravagance” and “frivolity.” This is why, when Jefferson’s political detractors wished to insult the wide-ranging scholar, they accused him of having his head in the clouds, and of being taken with extravagant or frivolous ideas. He did not respond visibly to provocation, however, reserving his ire for private letters and conversation with trusted friends, especially alter-ego James Madison; his outward behavior was so mild and accommodating that enemies could only condemn him by insisting that his mildness hid his “intrigue,” “fraud,” and “dissimulation.”

The opposite masculine type to Jefferson was, in the language of the time, “the man of furious resentment,” whose passions sometimes got the better of him. An example of this unattractive type would have to be the blunt, peevish, yet astonishingly successful Alexander Hamilton, Jefferson’s political nemesis in the 1790s. Hamilton’s sense of his own masculinity was expressed with far less subtlety: He craved military distinction; he charmed women. His temperament played a role in his sensational death.

As part of both the reserved and the bold masculine behavioral norm, no less than in the more narrowly circumscribed female behavioral norm, one was taught to behave as though one were being watched. Jefferson dealt differently with women in different spaces: In Parisian salons, in the 1780s, he adapted to a place where eager, outgoing female conversationalists were not sexually protected, nor felt they needed to be.

8 But he did not envision America as such a place. He was too easily reminded that the women of Europe were also adept at what Jefferson knew as “female intrigue”: Court politics included artful maneuvering by ambitious women, and Jefferson abhorred court politics. He wanted to preserve his nation from anything remotely resembling aristocratic-monarchical maneuverings. His political rise depended upon his ability to sniff out and eradicate that effete style of politics and replace it with the mannerly republican dialogue he considered the singular test of masculine prowess.

Mannerly republican dialogue and decorum sound desirable, but they are not, of course, a convincing rationale for insisting on female submissiveness. It is a lasting bit of curiosity for us that Jefferson could exhibit a modern liberal conscience in very visible ways—promoting public education, opening up political franchise to ordinary men, securing freedom of conscience—and yet be socially conservative, even for his time, in matters of race (as we shall see below) and gender.

Just as there were progressive individuals in his generation who agitated against slavery, there were those who, like Mary Wollstonecraft, insisted that the distinctions drawn between men and women on the basis of sensations, the nervous system, and “natural” affections, were false; aside from that which required brute physicality, women could accomplish whatever men could.

9 Yet it remained hard for a majority of nineteenth-century Americans, of either sex, to understand that female delicacy was a cultural construction and not a natural distinction. Popular writing, North as well as South, reinforced the notion that women needed to make themselves amiable and unassuming, as well as levelheaded; as “ladies,” they were to conform to the male image of what a woman ought to be, changing men’s minds passively by setting a moral example, and not by voicing criticism too openly.

Jefferson could not countenance female participation in politics, or in public office holding, as he indicated to the Swiss-born Gallatin, whose socially prominent New York–reared wife Hannah (née Nicholson) was, even when young, in her husband’s words, “a pretty good democrat.” But Jefferson sensed no threat from the women who wrote history, such as Bostonian Mercy Otis Warren; for history was a moral enterprise, and within his ideology women were meant to be guardians of virtue. For Jefferson, society was moving in an egalitarian direction, but not so fast that it should overturn gendered rules of conduct, or eliminate gendered spaces, in the process. Europe would do as it wished; New England would do as it wished. But Virginia must remain Virginia, wherein women were understood to be the special agents of sentiment and affection, and men were given the outward authority that enabled them to tap their inner strength and display vigor in all they did, while exhibiting sympathy and magnanimity in appropriate doses, at appropriate times.

10This is not to suggest that Jefferson disapproved of wit in a woman. Once again, his granddaughter Ellen, whose letters abound in wit, recorded that Jefferson especially prized the wit of his older sister Jane, who died before the Revolution.

11 Women could wield a sense of humor, provided it was neither loud nor ribald.

12 Ellen accepted the compromise of her generation: She grew up better equipped to deal with men in a variety of settings, because as America expanded and people moved about more and more, society could not always protect a woman. But this did not mean that women had to stop shedding tears—indeed they were still expected to, just as they were expected to place the highest value on love and motherhood.

Jefferson liked to encounter examples of traditional womanhood. When in 1816 he wrote a letter in support of a financially depressed Quaker acquaintance, the friend’s daughter struggled over how to write a gracious thank you that would be understood as sincere and not excessive. She tested the letter on her father first: “Though I deny having made any efforts at the sublime,” she addressed him, “I fear too thou wilt think some parts extravagant—do not, my father, for it is not

half I feel—I cannot think of him [the ex-president] with moderation. Great and excellent man!” The father repeated to Jefferson what his tender daughter had written. Acknowledging both father’s and daughter’s letters, Jefferson remarked of the latter that it was “acceptable . . . the sensibility expressed in hers for services so moderate shews a heart of great susceptibility, and which under your care and instruction promises to make happy parents and friends.” Here he represented the sincere and sober male protector of a woman who embraced her subordinate role. The entire exchange could just as easily have come from the tear-filled pages of a novel of sensibility.

13Throughout his life, Jefferson’s immediate family was chiefly made up of women. He produced no legitimate sons. Except for his eldest grandson and namesake, the males were rather young and, therefore, the recipients of less crucial communication (and consideration) from the patriarch. As an eldest son himself, Jefferson was fourteen when he lost his father, and he was closest to his elder sister as he was growing up. His mother survived until he was thirty-three, and though no evidence exists to enlighten us with respect to the emotional character of their relationship, she no doubt remained a presence in his domestic world. Because Jefferson’s wife died young and he did not remarry, he was especially concerned with the upbringing and education of their daughters in the 1780s and 1790s; the pattern would repeat when Martha produced daughters, and only the one son, Jeff, until a second and third came along toward the end of Jefferson’s presidency.

Martha had given him eight healthy grandchildren by then. The eldest of the girls, Anne, appears to have helped extensively with the domestic routine; details of household purchases over a period of several years appear in her handwriting in an account book that has been preserved. It was Ellen, of course, who most excelled intellectually, and it was she who ended up farthest from home. She was able to defend herself in “the world” as an adult, whereas Anne could not even defend herself against the brutality of her alcoholic husband.

Jefferson took a steady interest in his grandchildren, constantly giving gifts of books and posing questions at mealtime. Because there were more female than male Jefferson-Randolphs, Grandpapa, without intending on a national scale to implement a program for female education, could not help but undertake one at home. He could see in his own family that women in American society were growing sturdier, by and large, and that moral endangerment, the watchword of an eighteenth-century female’s rite of passage, was gradually becoming a less menacing phenomenon in the nineteenth century. But it was hard for one of his years, when it was so personal, to let go of old habits.

“Miss Edgeworth’s works. They are all good.”

In March 1818, protesting that his daughter Martha, as the mother of six girls, was a better judge than he of the practical means of educating daughters, Jefferson replied to a query from Nathaniel Burwell, scion of a powerful Virginia planter family, with “a catalogue of books” designed especially for young women. He prefaced his remarks by showing how deliberately he had planned ahead when, as a young father, he recognized that his own two girls were bound to be placed “in a country situation,” and remote from public schooling. Jefferson had directed his girls’ education so that they might in turn direct the course of study of their own daughters—and even sons, “should their fathers be lost, or incapable, or inattentive.” He was acknowledging that fathers often tended to be absent, both physically and emotionally.

14He praised dancing, drawing, and music. The first, he said, was “healthy exercise, elegant and very attractive for young people,” but not to be pursued by a woman after her marriage (he called this “the French rule”). His reasoning was twofold: Dancing was not physically “safe” for one who was meant to spend her years either pregnant or nursing; nor was it “innocent” after sexual activity had commenced. Drawing, he assured, was both “innocent and engaging,” and would serve a mother in her role as educator. Music, finally, “furnishes a delightful recreation for the hours of respite from the cares of the day.” In his own home, Martha and Maria had played harpsichord and pianoforte, and he had long before learned violin. As president, he occasionally sent sheet music home to his granddaughters.

Jefferson devoted much of the letter to Burwell warning of dangers. He fussed about the threat to young women’s minds and morals posed by novel reading, which was already a popular pastime. This was by no means Jefferson’s singular concern, but rather a standard complaint among well-educated men of his generation. In describing novel reading as an “inordinate passion,” and a “poison” that turns an impressionable mind against “wholesome reading,” he was merely echoing the words of ultra-conservative Noah Webster back in the 1790s: Webster had decried the “false and artificial sensibility” that “tickles the nerve and floats in the fancy, without leaving any impressions on the heart, or influence on the conduct.” Webster wanted men of distinction to oversee the dissemination of properly moral novels, so as to prevent easily influenced young women from obtaining a “discolored view of the affairs of the world.” For female physiology—a complex of unstable and dangerous energies—a “discolored view” meant that the nerves and associated sympathies would be misdirected and misapplied.

15Thus Jefferson could be patriarchal and undemocratic in his perception of literary authority, rationalizing his attitude, as Webster did, as an outgrowth of medical concerns. His greatest worry was that novel-reading young women would become romantically excited when they were supposed to remain calm and chaste. Given the professed delicacy of their nerves, he feared the mesmerizing effect of “figments of fancy,” as he put it to Burwell. Jefferson took the conservative line that a woman’s natural sensibility rendered her best suited for a life devoid of passion. The wrong kind of stimulation led to a debilitating nervous excitement or, in extreme cases, female hysteria or irreversible madness. This female addiction to novel reading corresponded to Dr. Tissot’s relentless warnings to men addicted to “the evil” of masturbation: “All the bodily senses, and all the faculties of the soul, weakened,” he wrote, occasioning “the loss of imagination and memory.” That is why imagination had to be moderated.

16The common denominator in medical and literary studies was acceptance that life was an adventure with consequences—a dangerous adventure often thrown off course or put out of balance. But it was invariably an adventure aimed at improvement, and it demanded resolve. Imagination was about temperament; it had to be monitored by the most rational of beings, just as scientific experiment had to be conducted methodically by those with the most training. But imagination always defined genius, and so it should not be stripped of its spontaneous quality, either.

Then why so much fear? Jefferson believed (as many others did) that among those most vulnerable, reading was a process that allowed sensations to circumvent the will and course through the nerves independent of judgment—indeed, sensations were capable of adversely affecting judgment. When one reads the wrong novels, as he told Burwell, “the result is a bloated imagination, sickly judgment”—

again, note Jefferson’s medical referent17—“and disgust towards all the real businesses of life.” Strong language.

But then he toned down his comments. Though relatively few, there were novels he wholeheartedly approved. Narratives that highlighted “incidents of real life” redeemed the novel form from what he called “this mass of trash.” Again, strong words. Our task is to establish, when it came to the content of fiction, where Jefferson drew a line for female readers and what his choices tell us about his imagination.

Under suitable novels, the first on his list was: “Evenings at home by Mrs Barbault.” Anna Letitia Barbauld, born the same year as Jefferson (he spelled her name “Barbault”), was most noted as a British poet. She was a dear friend of Jefferson’s dear friend, the dissenter and scientist Joseph Priestley, whom the Virginian had welcomed to America as a refugee from political violence in the 1790s. Barbauld shared Jefferson’s critique of English arrogance, composing verse in 1811 that anticipated haughty Britain’s gradual diminution on the world scene: “Yes, thou must droop; thy Midas dream is o’er.” It was presumably her political posture as well as her moral posture that suited Thomas Jefferson.

18Evenings at Home is something like

Aesop’s Fables in character, and directed toward the very young. Some of the readings are moral lessons, set in dialogue; others are akin to encyclopedia entries, and designed to impart knowledge. One describes the processing of paper from rags; another identifies bird species; all convey the values of kindness and frugality. The dialogue “between Mama and Kitty” teaches patience: “I hope you will allow, that mammas know better what is proper for their little girls to learn, than they do themselves.” The same tutorial also recognized that social classes exist, as determined by male authority: “It is usual to call all well educated women, who have no occasion to work for livelihood,

ladies; but if you will think a little, you must see that they live very differently from each other, for their fathers and husbands are in very different ranks and situations in the world, you know.”

Evenings at Home exalts female domesticity.

19

An assortment of novels Jefferson found suitable for young women, which he included in a letter to Nathaniel Burwell, March 14, 1818. Anna Letitia Barbauld published acclaimed poetry as well as juvenile fiction; Maria Edgeworth was, perhaps, the most influential female English novelist of the 1810s; the Comtesse de Genlis wrote her French stories for children in the 1780s, around the time Jefferson and his daughters were in Paris; William Godwin was a radical political thinker as well as a celebrated novelist. Library of Congress.

Jefferson’s selection of Barbauld is followed by a notation: “Miss Edgeworth’s works. They are all good.” Maria Edgeworth (1767–1849) was by this time the author of seven novels and various essays and short stories. Born in England, removed to Ireland in her teens, she marveled at the color and charm of Irish habits and speech, and wrote of them with a mixture of appreciation and good humor. More to the point, she captured the mischievous ways of people from all social classes. Her wealthy, sophisticated father, Richard, introduced her to the world of country houses that she wrote about—often in collaboration with him—though her reputation as a singular wit was entirely deserved.

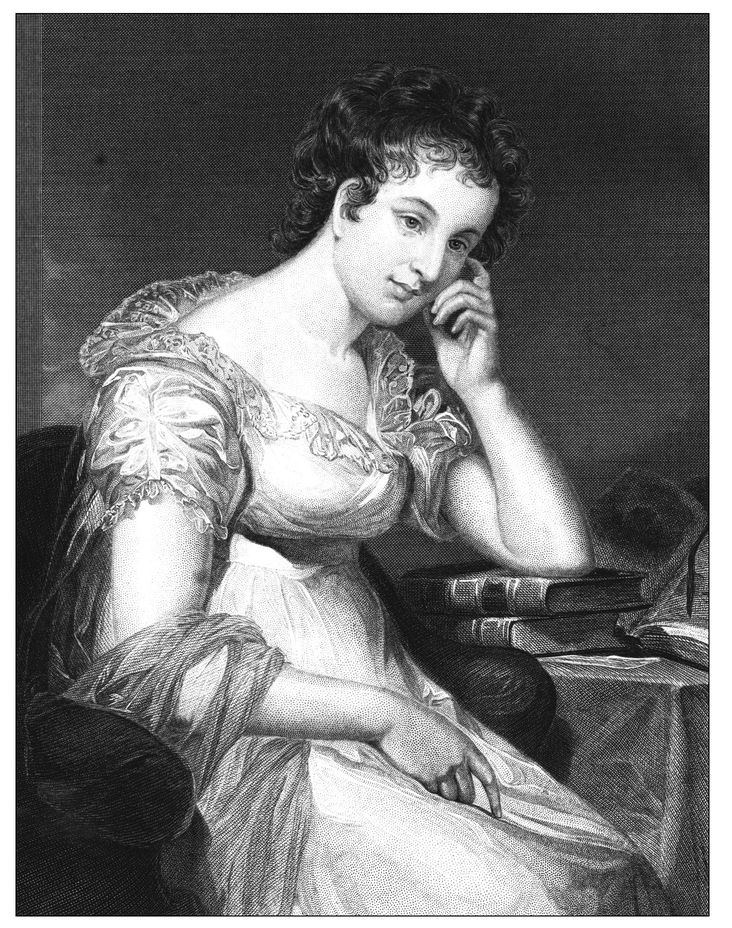

Maria Edgeworth, from a mid-nineteenth-century engraving.

Her first and most influential novel,

Castle Rackrent (1800), is really a novella, narrated by an old servant named Thady Quirk (“honest Thady”), whose deadpan helps her poke fun at Irish aristocratic life and manners. The men tend to be well liked, rakish, inebriated, and debt-ridden; when they are not imprisoned in bedrooms by husbands or fathers, the women remove themselves from the action. Silly, outlandish, and perfectly brutal goes the novel as it chronicles the slow disintegration of a landed gentry family. Castle Rackrent’s lovable Sir Condy serves as a distorted mirror image of Jefferson; an unselfish trust (the value they place on friendship) destroys both men’s fortunes.

20But that is not the message contained for Jefferson in Maria Edgeworth’s prose. Her mobile imagination fit his moral definition of the good female-directed novel. So then, how could the satirical Castle Rackrent correspond with Jefferson’s insistence that the female imagination was in need of monitoring? The answer is not immediately obvious. First, although he wanted young women to be reserved in their romantic inclinations, he did not prefer them dull. Convinced that Edgeworth’s brand of humor did not awaken repressed desire, but only entertained (with a douse of sympathy to the human condition), he was not worried in the manner Noah Webster’s words conveyed.

To critique the fashionable world, to mock even the gentility he himself exhibited, was quite all right with Jefferson, so long as it was life affirming. As a young man, he had adored Laurence Sterne’s big and small productions, Tristram Shandy (1759–1767) and A Sentimental Journey (1768), taken together the eighteenth century’s most profoundly irreverent examination of the soul. So there was precedent for Jefferson’s approving a novelist’s unconventional approach to morality. He preferred a string of jesting, wit-laden vignettes to the coldly admonishing manner of an orthodox minister; the former tapped into conscience at least as well as the latter.

In the plot-free

Tristram Shandy, conscience reigns, and self-absorption becomes imaginative sympathy as the novel progresses. Satire is rich, but never mean-spirited, and laughter, the most human of human expressions, is expected. Sterne was part of the intellectual set that was most responsive to the new physiology by exploring nerves and sensibility and the action of the brain. He proved himself inventive (and often hilarious) by associating the mysteries of delicate sentiment with the failure of eighteenth-century physicians’ abstractions to explain the variability of life.

21In Sterne, as in Edgeworth, the warm imagination is turned inward, and wit points outward. Jefferson invited both. Rather than devolving into an austere moralist, he sought to be a good-humored one, à la Benjamin Franklin: He told Jeff Randolph, and others of that generation, that good humor was the first quality of mind to be cultivated.

22 His granddaughter Ellen recalled his outlook: “He enjoyed a jest, provided it were to give pain to no one, and we were always glad to have any pleasant little anecdote for him—when he would laugh as cheerily as we could do ourselves.”

23Jefferson’s ideal of domestic harmony required a female to be poised, not grave. In appreciating humor, she was constrained only from laughing too loudly—uproarious laughter was a sexually suggestive sign at this time. Jefferson would have concurred with the conduct book author who wrote in this vein: “There is still all the difference in the world between the entertainer of an evening, and a partner for life.” That is, a woman had to engage a man’s sympathetic consideration, and not behave in such a way that she might lose it.

24 In short, Jefferson admired wit in an author, humor when affectionately aimed, and self-possession in women. He appreciated the comic absurd, which, as a high form of critical thinking, did not teach impractical behavior, nor provoke a nervous reaction, nor promote unreal expectations from romance.

25Edgeworth left Castle Rackrent behind and took up more conventional writing. Her subsequent novels, beginning with Belinda (1801), were social commentaries, less idiosyncratic than Castle Rackrent and melodramatic in varying degrees, their female characters speaking volubly and grappling with the most human of problems, often brought about by the male vices of drinking, gambling, and dueling.

In

Belinda, the title character is affable, well educated, possessed of the desired feminine traits of the day, and therefore a suitable match for a trustworthy male. One is found in Oxford-educated Clarence Hervey, chivalrous and humane, but “easily led” and “so dreadfully afraid of passing for a pedant that when he came into the company of the idle and ignorant, he pretended to disdain every species of knowledge.”

26 It is a novel that highlights the choices facing a girl as she takes the stage of life. When does a woman accomplish most by remaining “soft”? What dignifies a man’s character? Edgeworth is trying to define gender roles and moral boundaries.

But the novel really centers on the manipulations of Belinda’s on-again, off-again confidante, the socially adept (“Every thing that her ladyship said was repeated as witty”) but inwardly confused Lady Delacour, a woman with a past. In a typical chapter, “The Mysterious Boudoir,” the reader is witness to the extravagance of female passions, as induced by delicate nerves. Before “convulsions” take over, and amid “shrieks” and other signs of pain, the supposedly dying Delacour begs for a double dose of the opiate laudanum. The prudent Belinda repeatedly refuses, calling for the clever Dr. X___, who provides the correct prognosis. The patient survives and mends her ways, and the characters are all settled in their lives when the story ends.

27At once acknowledging her prescribed femininity and mocking the literary stereotype that extends from it, Jefferson’s prized granddaughter Ellen expressed the learned fears and tempered vulnerabilities of a proper woman of sensibility: “I have been suffering from one of those ‘maladies de langueur,’ so common in our country and climate,” she wrote her brother-in-law in 1823. “The disease whatever it is, has for the present settled upon my nerves.... I would not have you suppose from this that I am giving myself any fine lady airs, I will assure you that there are no shrieks, nor fits, nor tears, nor tremblings in the case, I have ‘executed no elegant outrages’ nor excited one spark of ‘tender admiration’ by my fascinating weaknesses.’ No one from common observation would perceive that anything was the matter with me.” The key to a young woman’s success, as Ellen understands it (her grandfather would agree), is to maintain a “vigorous mind” and “force of character” amid challenges, even those inwardly generated.

28In Edgeworth’s

The Absentee (1812), the stakes are slightly different—life under a financial cloud—but maintaining friendships and making sound choices remain key elements. The young and deserving Lord Colambre consistently refuses to yield to caprice, and is rewarded for it. As in all such novels, deception abounds. An ambitious woman has designs on the unsuspecting hero: Her “whole figure . . . suddenly metamorphosed; instead of the soft, gentle, amiable female, all sweet charity and tender sympathy, formed to love and be loved, he beheld one possessed and convulsed by an evil spirit—her beauty, if beauty it could be called, the beauty of a fiend.”

29 Where human feeling is being defined, “convulsions” are transparent markers, as useful to the plot as the moral peril that tests the hero or heroine.

Edgeworth places women at the heart of her novels, but she as clearly requires the social order to be sustained by a benevolent patriarchy. In

The Absentee, perhaps the most outstanding example of this, the garrulous, well-intentioned Lady Clonbrony is completely irrational for most of the book. Her practical-minded son Colambre must demonstrate over and over how her erratic behavior threatens the happiness of the whole family. Colambre’s love interest, Grace, possesses just the right degree of “pride” (dignity) that he wishes his mother owned, as well as “affectionate tenderness,” “indefatigable patience,” and “strong attachment.” Edgeworth’s women give up a certain amount of autonomy in return for what one scholar calls “new-style patriarchy,” in which “children learn to respect authority when that authority wears a benevolent and disinterested countenance.” One can see a Jeffersonian domestic order in this.

30Maria Edgeworth never married. She is often compared to her contemporary, the better-known (at least to later generations) Jane Austen. But Edgeworth’s writing is generally considered less pious, less judgmental, and Jefferson’s family must have been quite comfortable with female characters who recognized temptation and were yet dutiful to Jefferson’s call for mental and moral balance. Jefferson himself refrained from taking high-handed control over his granddaughters’ marital prospects; he was content to instruct with loving concern. Picturing the Jefferson-Randolph women as well read yet appropriately modest, competent hostesses and superior conversationalists, he could associate Edgeworth’s moderate tone with home life at Monticello.

He was proud of how loyal Martha turned out, and now hopeful about his granddaughters’ future, too. He had overseen his elder daughter’s education from the time of her mother’s death in 1782, when she was ten; in a similar way, Maria Edgeworth had lost her mother at the age of five, and her equally largerthan-life father, a patriarchal moralist, came to share (if not dominate) her literary voice. What is interesting, then, is the question of subliminal control.

Thomas Jefferson and Richard Edgeworth were publicly prominent men who seem to have given primary shape to their daughters’ intellectual and emotional lives. Martha Jefferson Randolph had early on internalized the command that she find her proper place in society as wife and daughter, and that she simultaneously fulfill her father’s need for a partner to oversee the domestic routine and comfort him whenever he emerged from his embattled position in the political realm.

Granddaughter Ellen, living at Monticello from 1809, replayed this role. She grew so enamored with Maria Edgeworth’s imagination that she analogized her own experiences accordingly. Years afterward, married, and accommodating herself to her Boston surroundings, she learned—“this gossip came to me doubly distilled through the mouths of two servant girls; Mrs L__’s and my own”—that a matron in the vicinity had no patience for small children. Ellen, now a mother, wrote in her private journal: “I have a worse opinion of servants than Miss Edgeworth herself, & have freely expressed my disapprobation of those ladies who listen to their tattling.” Even her style of writing has an Edgeworthian ring to it. Though domesticated, Mrs. Joseph Coolidge retained her sharp powers of observation and presence of mind, as her grandfather most certainly would have advised—and as Richard Edgeworth would have advised his daughter, too.

31In

Belinda, Maria Edgeworth originally intended Lady Delacour to sink under the weight of her own recklessness and die, and for Belinda to be pursued by the dissipated Lord Delacour before coming into an inheritance and landing on her feet. Revealingly, it was Maria’s strong-willed father and collaborator on the novel who tampered with his daughter’s art. Though she later wrote that “there was no danger of offending or of disappointing him by not using what he offered,” it seems clear that he wanted to replace her simpler, more calamitous narrative solution with his own pedagogy. It was he who had spirited her away from her sympathetic comedy of manners,

Castle Rackrent, and directed her to a heavier-textured appraisal of virtue and vice. And so we must seriously ask, with which perspective did Jefferson identify more readily? Maria Edgeworth’s or Richard Edgeworth’s?

32There is another way to approach this question: Did he identify with the female novelist from a patronizing perspective or from a genuinely admiring one? There was no question about it for Sir Walter Scott, the most celebrated male novelist of the decade of the 1810s, who proclaimed himself in Maria Edgeworth’s debt. It is difficult to draw a sure conclusion about Jefferson, because he read less and less fiction as he aged; it is just possible that his daughter Martha and her brood prompted his statement “Miss Edgeworth’s works. They are all good.” The two younger generations were not fans of the author merely because of Grandpapa, but rather because Edgeworth wrote of a society that resonated for them—and they had no doubt read more of her works than he had. At least we can say that they would not have helped tailor such a list if it did not entirely coincide with Jefferson’s tastes.

33

A Fictionalized Jefferson?

In her preface to

Castle Rackrent, Edgeworth wrote: “That the great are not as happy as they seem, that the external circumstances of fortune and rank do not constitute felicity, is asserted by every moralist.”

34 Think now about the felicityseeking Jefferson, protective of domestic life, peering out from his pastoral retreat with general satisfaction. How knowable is this man? He entertained regularly but he plainly cherished his privacy. He set his private quarters apart from the rest of the downstairs at Monticello, and he enclosed this space behind louvered shutters. Venetian blinds allowed him to regulate incoming light while controlling access—even visual access—to his physical person. In the dining area across the large hall from these quarters, especially at the 3:30 P.M. main meal, he gave himself over to company.

35As a man with a well-defined domestic routine, the engaging, multifaceted Jefferson held a unique position in his community. He might be considered a Virginia version of Maria Edgeworth’s Irish landowners, distinguished from the English plantation model, yet still influenced by it. She calls her tale a “biography.” Does it somehow encompass him? After all, we must already feel his life at Monticello describable in storied terms.

Perhaps the most intriguing possibility is this: that Jefferson was introspective enough to see his own life as one an inventive writer might be inspired to fictionalize. Here he was, the workaholic patriarch, cataloguing and tabulating his life, busy amid his gadgets and drawings, communicating eagerly with distant friends, clamoring to know what new ideas had emerged in the wider intellectual world, yet just as busily focusing on the immediate, and taking notes on the efficiency of his plantation labor force. We can envision him as he must have been from time to time: gazing at the skies, charting changes in the weather and in the growth of plants, all the while conceiving a university in the neighborhood, quantifying its needs, preparing an inventory of required books, and a means to attract promising students and a superior faculty. Was his creative empathy sufficient to restrain him from feeling “greater” than the more typical men with whom he daily interacted? Is not such a man tempted to consider himself a human phenomenon, one who is even more than a political icon?

He left a tidy collection of letters, copies of those he had written and originals he had received, totaling some 16,000 of the former and 26,000 of the latter.

36 His life was already a book-in-the-raw. The creative possibilities within language seemed endless to the thinking revolutionary—one can almost hear him speak at supper words he wrote in 1821: “Science must be stationary unless language advances pari passu” (at the same pace). He seemed to spend his days playing with forms of words, as much as he was adapting technology: “Judicious neology can alone give strength & copiousness to language and enable it to be the vehicle of new ideas.”

37 Of course, such a public figure—holding court at his legendary dinner table—would have been an object of immense curiosity.

Ellen presumed that other Virginians looked upon his French style of dining with “good-humoured indulgence.”

38 Did he acknowledge himself this way, as outsiders saw him? Could he at all imagine himself, a graceful yet set-in-hisways ex-president in his seventies, as the subject of anecdotes, gently spoofed in an Edgeworth-type tale? In 1823, the Marquis de Lafayette wrote to Jefferson asking whether he had seen a “moral novel,” titled

Oriele, in which the hero is traveling in America and “has the pleasure to converse with Mr. Jefferson.”

39 Was he conscious that he was a

character?

One thing Jefferson, as letter writer, regarded with intense interest and concern was emotional hurt and how the human mind dealt with disappointment. So perhaps the appeal of Edgeworth had something to do as well with a literary penchant to ruminate about human imperfection, grief, and misery. The tenor of his letters in the middle years of his retirement indicates that Jefferson felt himself in decline; he was contending with physical limitations, concerned that his intelligence and fortitude would not be enough to enable him to prevail over pain and weakness. Certainly his letters to John Adams during this period attest to that. He wrote straightforwardly of human frailty, of mortality, here criticizing Napoleon for his cold-bloodedness, there nostalgic for the eighteenth century: “While the world is thus turned up side down, on which side of it are we?” he asked preciously.

40It would be absurd to claim that he had a death wish, even at the end. Yet faced with uncertainty, he was many times tempted to withdraw, wanting not to engage, not to be seen. That was one reason why, toward the end of his presidency, he began to build himself a second retreat, on property three days distant by carriage in the southwestern part of Virginia—his charming, octagonshaped Poplar Forest home. He went there two or three times a year in the mid-1810s, as construction proceeded. He went, usually for months at a time, to escape the bustle of Monticello. “I have fixed myself comfortably, keep some books here,” he wrote to Benjamin Rush in 1811, “am in the solitude of a hermit, and quite at leisure to attend to my absent friends” by letter.

41A half year before he wrote the letter to Nathaniel Burwell, he visited Poplar Forest and took two granddaughters with him, twenty-year-old Ellen and eighteen-year-old Cornelia. His favorite servant, Burwell Colbert, rode on horseback alongside their carriage. The little family took walks and occasional rides, sat together and read regularly at times set by Grandpapa; sometimes Jefferson read aloud to them. Here his mind was generally undisturbed, his eye focused. When he complained to the architect Robert Mills about his weakened faculties, he had to qualify: “sight excepted.” He wore glasses only for small print, and he did not consider his distance vision impaired. At Monticello, when not entertaining guests, Jefferson spent his evening hours in retirement reading as much as possible. “Doctr. Franklin used to say,” he wrote Abigail Adams, “that when he was young, and had time to read, he had not books; and now when he had become old and had books, he had no time.” Jefferson made time. As his slave Isaac put it, “Old Master had abundance of books; sometimes would have twenty of ’em down on the floor at once—read fust one, then tother.”

42At Poplar Forest, he kept a stock of British, French, Italian, Greek, and Latin poetry, more than one hundred volumes, to share with his granddaughters; then there were the latest books acquired at Monticello, which he carried down for extended visits. He made sure, at Poplar Forest, that he was rarely distracted, so that he had more spare time for his favorite amusement: “Reading when I can be indulged in it, is the elysium of my present life,” he wrote to a Dutch intellectual in 1818. Not only did he discuss books in letters to his friends, he leaned on his bookbinder to supply wanted books in exquisite leather: “[I] am impatient in being so long out of the use of my books,” he wrote in the spring of 1819. Finally receiving shipment—“I am so well satisfied with your bindings”—he instantly issued a new order and named the one boat he trusted to carry his next precious cargo: “Bind them all in your best manner, gilt and letter according to the labels, & above all solidly pressed.” His country neighbors gaily referred to Jefferson as “squire.”

43Approving Maria Edgeworth’s fascination with the domestic activities of country squires does not mean that Thomas Jefferson found felicity in the publicity of his own domestic affairs. Far from it. It was something he endured. Long before his retirement began, the literate world already knew a great deal about the master of Monticello. The Marquis de Chastellux visited Jefferson in 1782, and famously described the gentleman architect as “the first American who has consulted the Fine Arts to know how he should shelter himself from the weather.” In his

Travels in North America, the French aristocrat accorded the Virginia planter the high praise that first established his reputation as a worldly provincial: “No object has escaped Mr. Jefferson; and it seems indeed as though, ever since his youth, he had placed his mind, like his house, on a lofty height, whence he might contemplate the whole universe.” This was well before most of his countrymen even knew that he had authored the Declaration of Independence.

44Another French writer, the duc de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, visited Jefferson at home in the mid-1790s, and published an English account of his travels in 1799. He discussed Jefferson’s methods of cultivating land, noted how much each bushel of corn earned him, gave Jefferson’s thoughts on apportioning the energies of his field slaves, revealed how the master directed his other slaves (“He animates them by rewards and distinctions”), and alluded to the domestic lives of Jefferson’s (then) two daughters. The duc could not resist the subject of miscegenation on Virginia plantations, for which white employees, rather than employers, were assigned paternal responsibility.

45Whatever the Sage of Monticello, as the entertainer of many travelers, illustrious and ordinary, thought of these published accounts, he often pondered what it would take to keep his private life private. In spite of the remoteness of his situation, the restless political environment drew attention to him. Did he anticipate that not all visitors’ observations would be favorable? The most impertinent instance of intrusive journalism was, of course, the scandal over Jefferson’s suspected involvement with his house servant Sally Hemings, which erupted in 1802.

Jefferson the builder and dreamer shopped for works of science and philosophy. Yet he also apparently developed a taste, or at least a tolerance, for the kind of literature that in fictional form dwelt upon house and locality, and private foibles. Perhaps he approved of Maria Edgeworth because she consistently defended his world of caring gentility. Certainly she gave voice to bookish, spirited, industrious women. Above all, she symbolized clarity, prudent reflection, and female common sense.

Jefferson and his female progeny appreciated the novelist’s self-confidence as well as the compassion she felt as a creator. As in his earlier reading of Sterne, Jefferson must have responded to Edgeworth’s conviction that good fiction caused the human spirit to surface in artistic glimpses of a noteworthy person’s domestic life and uncensored thoughts; and that these glimpses, properly understood, contributed to moral improvement.

46 Exposed as his celebrity made him, our nearly fictional Squire Jefferson had his large and growing brood of grandchildren to educate in the Edgeworthian mode, and this no doubt grounded him.

“wicked and tyrannical men”: Godwin’s Caleb Williams

Standing apart on Jefferson’s list of prescribed female reading is William Godwin’s 1794 novel

Things as They Are; Or, the Adventures of Caleb Williams.47 Among the few contemporary novels recommended, it is the only one written by a male. The story is one that mixes lessons about the desire for heightened human sympathy with a critique of the arbitrary power inherent under a rigid class system.

In the early nineteenth century, everyone had heard of Godwin (1756–1836). His name was as recognized internationally as Jefferson’s, and he was no less controversial. He had begun life in England as a dissenting minister, and he espoused a radical view of politics that Jefferson thoroughly approved. Godwin was one of a few robust British writers who embraced the tumultuous French Revolution. He disputed the reactionary sentiment of Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), which famously upheld the values of the conservative state. Godwin’s Enquiry Concerning Political Justice (1793) was a bold endorsement for individual self-affirmation, rich in the vocabulary of natural rights. Only the emigrant Thomas Paine, whose Common Sense prompted Americans to declare their independence in 1776, was a half-step ahead of Godwin, having answered Burke with his resounding Rights of Man (1791–1792). Paine openly attacked the perversions of Christian religion, and he scoffed at monarchy and aristocratic pretense, which he claimed to be archaic forms due to be cast into oblivion in the enlightened, modern world that the political radicals wished to bring about.

As with Barbauld and Edgeworth, there is no doubt, once again, that Jefferson’s selection of Godwin’s novel was influenced by more than literary method. Jefferson was the American-born counterpart to Paine and Godwin. At the time that his political personality was permanently refashioned into this more radical set of values, he was serving as George Washington’s secretary of state. He led the political faction that saw events in France hopefully. The radical intellectuals, idealists all, aimed to upset the elite monopoly of power; they caused conservatives to shudder at the prospect of the anarchy and atheism that “democracy” might bring with it.

It is worth noting, too, in this context, that Jefferson’s 1818 letter to Burwell highlighted the value of teaching young women the French language and making the best French literature available to them. “The French language,” he wrote, “become that of the general intercourse of nations, and, from their extraordinary advances, now the depository of all science is an indispensable part of education for both sexes.” The juvenile guide

Evenings at Home, by Barbauld, explained to young girls that though they might never visit France, learning the language remained important: “There are a great many books written in French that are very well worth reading; and it may every now and then happen that you may be in company with foreigners who cannot speak English, and as they almost all talk French, you may be able to converse with them.” His selection of the instructive stories of the Comtesse de Genlis, aimed at young girls, shows that Jefferson believed that a mastery of French was important at an early age. Jefferson was America’s best-known Francophile; he rejected the exaggerated English style of class privilege and wished his countrymen and women would escape the British cultural as well as political orbit.

48Godwin’s controversial ideas played out in the conflict of the 1790s between Jeffersonian Republicans and the Anglophile Federalist party of George Washington and John Adams. British domestic repression was matched in the United States by passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts in Congress on the eve of Jefferson’s successful bid for the presidency. The Federalists’ outright suppression of First Amendment speech led to show trials and the imprisonment of writers, of any nationality or background, who criticized government policy. Jefferson decried this “reign of witches” and held out the hope of realizable political equality for common men.

Here, then, was the crystallization of Jefferson’s cause, where all doubt in his mind disappeared. Either America would follow the road back to monarchy and tyranny, or it would continue on the path to popular sovereignty that he saw embodied in the spirit of 1776 and tenuously pursued in Revolutionary France. There was no more boldly drawn line charting direction.

The question, then, is why a novel containing an overtly political message belonged so prominently on Jefferson’s short list of novels for young females. The answer, at least in part, is that Jefferson believed that as one facet of their education, without encouraging them to take the political stage, women should be taught to distinguish in a man between a soft, sympathizing republican temperament and a hard, unfeeling aristocratic temperament. He may have desired that women remain politically harmless, but he did not want them politically uninformed.

The story of Caleb Williams is a meandering one. The hero of the opening volume (of three) is the levelheaded Mr. Falkland, a prosperous landowner who, in volume two, will employ the socially unexceptional Caleb. Falkland is cast against the acerbic Squire Barnabas Tyrrel, whose “diseased imagination” makes him obsessively jealous and controlling.

Every reader attuned to the prevailing culture of sensibility would have instantly recognized Godwin’s purpose in constructing these two characters: One was beyond reproach, the other heartless. The novel of sentiment put its characters on trial for their moral lives. One character’s sensibility defined tenderness—male reformation—and the other was entirely unable to resist taking advantage of the female state of delicacy.

49Squire Tyrrel is to the novel what King George III is to Jefferson’s Declaration: an unfeeling tyrant. The “diseased imagination” Godwin attributes to him is, once again, a medical characterization; it describes a person who has allowed his or her nervous system to overwhelm the capacity to reason. Tyrrel turns his attention to fragile, hopeful Emily Melville, his orphaned cousin, whom he torments and drives to an early grave, in part because she becomes enchanted with the upright Falkland. Emily sees no evil, believing virtue an invincible shield. Only Mrs. Jakeman, the elderly housekeeper whom she has adopted as a surrogate mother, is able to detect that Tyrrel is set on conquering the virgin’s will. Mrs. Jakeman counsels: “There are very wicked and tyrannical men in the world.” Every victim in the novel is given melodramatic parting lines; before she breathes her last, Emily forgives her brutal oppressor.

50Before volume one concludes, Falkland’s fate, too, must be sealed. In avenging those whom Tyrrel has destroyed, he kills Tyrrel, but allows two innocent farmers to be executed for the murder. Knowing what he has done causes Falkland to wish for “insensibility;” the murderer becomes a “rigid recluse.” He becomes a different person.

51Enter Caleb Williams, a curious, intelligent young man who has (as he himself narrates) yet to discover “the world and its passions.” He enters into Falkland’s service, and almost immediately begins prying into his past, looking to uncover secrets. “To do what is forbidden always has its charms,” Caleb admits, cooing: “To be a spy upon Mr Falkland!” The recluse grows suspicious that his hired man is out to solve Tyrrel’s murder.

52In his mounting psychological struggle with Falkland, Caleb remains caught up in the hazardous world of sensations. He confesses that each recollection of the danger he was generating for himself “gave a kind of tingling sensation not altogether unallied to enjoyment.” He elaborates: “The further I advanced, the more the sensation was irresistible.”

53 Finally, Falkland owns up to everything. He had planted the bloody knife that sealed the innocent farmers’ fate and so preserved his own social station. “This it is to be a gentleman! a man of honour!” Falkland exclaims. “I was the fool of fame.”

54The two men’s destinies are joined. It is a fight to the finish; one or the other will lose everything. For much of the final two volumes, the underdog Caleb is pursued by Falkland’s personal police force—the arm of privilege. For accusing “the master,” Caleb must suffer a series of unspeakable torments as he runs, hides, is captured, escapes, trusts, is betrayed, and along the way develops the self-preserving weapon of disguise (here an Irishman, there a Jew) to avoid recapture. Through it all, the formerly mild and generous Falkland exhibits a powerful obsession: the need to destroy Caleb just as the vindictive Tyrrel had once needed to destroy those whom Falkland had befriended. “It was a million of men in arms against me,” Caleb expostulates at the height of the pursuit.

55 Falkland retains the advantage, because in a society such as theirs, his “truth” will always outweigh Caleb’s.

Which emotion will win out: sympathy or the desire for vengeance? This is what lies at the core of Godwin’s drama. The hunter and hunted feel the same conflicting emotions at various times in the novel. But when Falkland is left “convulsed” with “fury,” his passion unchecked, Caleb persists in his journey of self-discovery; he emerges the stronger man by learning the value of openness.

At the end of his tale, standing before a magistrate, Caleb is able to unburden his heart with self-effacing innocence. In doing so, he overawes Falkland. Although armed with his truth, he refuses to brand his tormentor a murderer, calling him instead “a man worthy of affection and kindness.” As he lets his resentments go, he finds absolution: Sympathy and sincerity conquer Falkland, who rises to confess his crimes. As Caleb tells it, “He saw my sincerity; he was penetrated with my grief and compunction. He rose from his seat, supported by the attendants, and—to my infinite astonishment—threw himself into my arms!” Something in Caleb’s conciliatory voice had cleared the fog of old society privilege and obliged Falkland to surrender to emotional democracy.

56This is an essentially Jeffersonian ending, for Jefferson had predicated his career on the ideal of fashioning social harmony: “We are all republicans, we are all federalists,” he pronounced in the Senate chamber in his most heralded attempt to leave behind the “throes and convulsions of the ancient world,” and bind the nation. The first inaugural address was meant to embrace those among the political opposition whom Jefferson called “candid” Federalists, men still strongly identifying with the old regime of wealth and privilege, but equally responsive to the appeal of republican sensibility. Jefferson, like Godwin, believed that there were Falklands to be converted, melted by the language of enlightened republicanism; Jefferson and Godwin each wanted to believe that class tyranny would be crushed in the natural course of human events.

It is intentional in the novel that Falkland, unlike the deviant Tyrrel, is “a man of the acutest sensibility” throughout. In a subsequent novel,

Fleetwood: Or, the New Man of Feeling (1805), Godwin refinished the sentimental man, the real Jeffersonian: humane, susceptible (sometimes acutely so), and aided by the moral imagination. Years later, Ellen Coolidge referred to her father, Thomas Mann Randolph, as “a near resemblance” to Fleetwood, an intense man with a heightened sense of honor, undone by his passions and jealousies and violent outbursts. Though decidedly flawed, at times torn by contradictory emotions, the Fleetwood type was always able to express friendship by attending to his natural feelings, and he had a palpable sense of social justice.

57The Godwinian hero is a natural republican, typically stripped of a father figure when young and obliged to take charge; he is aggressive without wanting to appear so, unaware that he can be weakened by his need to control—by his own occasionally despotic tendencies. He is, indeed, very much like Jefferson himself.

Nothing deters the Godwinian hero from perceiving justice in sublime terms. Caleb speaks Godwin’s mind:

I was born free: I was born healthy, vigorous, and active, complete in all the lineaments and members of a human body. I was not born indeed to the possession of hereditary wealth; but I had a better inheritance, an enterprising mind, an inquisitive spirit, a liberal ambition.

58In his last public letter, on June 24, 1826, Jefferson wrote similarly, with his thoughts on the upcoming fiftieth Fourth of July:

The general spread of the light of science has already laid open to every view the palpable truth, that the mass of mankind has not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few booted and spurred, ready to ride them legitimately, by the grace of God.

59Yet even

Caleb Williams does not progress beyond eighteenth-century literary conventions in its depiction of women, though Godwin himself unquestionably admired the female intellect. He loved the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, author of the powerful

Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792); their daughter, Mary Shelley, was the very public author of the classic

Frankenstein (1818), which she dedicated to her father. It is curious that both

Caleb Williams and

Frankenstein were confessional in nature, and dealt with extremes of curiosity, the penalty for selfishness, and the conscience under attack.

60Were Jefferson to apply the lessons of Godwin’s life, he might have reconsidered the arbitrary power that American men, and Virginians in particular, exercised over domesticated women. But such sentiments were not within Jefferson’s reach. He had enjoyed warm friendships with strong-willed women, but he did not desire to import outside gender roles into Virginia. He preferred that women master the household economy first, and learn to be interesting and charming second. Their only ambition should be artistic—in other words, nothing that might lure their imaginations to desire a level of public distinction beyond what their industrious husbands could generate. He wished to insure harmony by confining females’ stimulation to moral pursuits such as drawing and uplifting reading.

Jefferson undoubtedly liked Godwin’s novel best for its embrace of the sentimental individual whose decent yearning for private felicity placed him in opposition to the oppressions of society. He most likely saw in this book the same things the friendly critics in 1794 admired: It set forth “a first principle that virtue consists in justice,” showing that what is commonly considered honor is not necessarily so. It also caused the reader to regret that a “mad passion for reputation should suppress every feeling of humanity”; and it exposed “oppression which is often practiced under the form of law.”

We can see how the novel remained Jeffersonian in 1818 by reading the words of a critic of that year, prominently reviewing a later edition. William Hazlitt noted that Godwin’s writing successfully bridged the ideal and the real: “By an intense and patient study of the heart ... the author launches into the ideal world, and must sustain himself and the reader there, by the mere force of imagination.” Hazlitt, a well-known British essayist, concluded: “This novel is . . . one of the most original as well as powerful productions in the English language.”

61Jefferson saw Caleb Williams as fiction suited for young women because a) it taught that the end of life was to foster inner contentment; and b) it did not challenge gender barriers in place. Self-monitoring, which led to self-improvement, all but guaranteed the repose that Jefferson coveted. Everyone, house servants and overseer included, remarked on his unexcitable temperament. This traditionally feminine quality found expression in the subtle demands he placed upon the young women in his family.

Just as viewing the results of his inspired building projects leads us to marvel at the balance in Jefferson’s mind between order and liberation, a glimpse of his literary imagination helps us to better appreciate his campaigning psyche. We have come to know him as a great doer. When we think of him as a reader (which he was for hours each day, several volumes propped up at a time on the revolving bookstand in his cabinet), we imagine him absorbing new knowledge and ancient ethics from across the ocean, and it seems that his heart was as pure as a man’s could be for one so politically driven.

But there were flaws in his judgment. We know that. He could not deny that he owned other human beings, and that his loftiest words—“All men are created equal”—were a lie, even if by “men” he meant only enfranchised men, white men with independent public roles. And no matter how well he studied or how many letters he wrote in a salute to the Enlightenment, at the end he could not escape one grim fact of life. It came to him as he was sinking physically: He was unable to pay any longer for his dreams.

In the pursuit of “tranquil permanent felicity,” a tyrant spirit was lurking. Indeed, just as in Maria Edgeworth’s Irish sagas, Death stalked the restless patriarch.