In copying the accounts of his parish into a book, Sir Christopher knew that he was writing for posterity. The account book was more than a ledger to keep trace of income and spending. It was an archive, designed to record the benefactors of the parish and ensure that they were prayed for, to inform the wardens of their responsibilities, to record collective decisions binding ‘ever here after by this boke', an oracle to be consulted in time of dispute.1 Its margins are littered with cross-references and notes sign-posting particular entries for the benefit of the reader thumbing through it: ‘not[e] the store of Sent Sydwyll', ‘not[e] my fader ys gefte', ‘not[e] the bordis that restyth', ‘not[e] the plumer', ‘not[e] debz to the black vestments', ‘The cownte of the yong men Wardyns in anno domini 1543, loke the 24th leve be fore and invenies [you shall find it]'.2 These are essentially index marks to the file copies of the annual accounts, handy pointers to facilitate reference to an originally oral text. But some items included in the book were quite clearly composed in the first place not to be heard, but to be read. Almost all of these are designed in some way to consolidate the parish's identity and unity, or to heal or forestall division. The keeping of records was thus an aspect of the priest's role in the ‘social miracle', the religious healing and sustaining of the bonds of community.

Perhaps the most notable and most obviously religious of these insertions into the Morebath account book is the long and detailed list of benefactions which Sir Christopher compiled in 1540, recording every gift, great and small, made to the church since his arrival twenty years before. The document opens like a public, oral text, with an injunction to prayer: ‘Orate pro animabus sequentibus [pray for the following souls]'. This makes it sound as if it were the parish bede-roll, the list of benefactors read out at the annual Palm Sunday commemoration.3 But the Morebath bede-roll was almost certainly less detailed, consisting probably of just the names of the dead, and it was definitely a different document, which has not survived. In 1539 Agnes Adams, the daughter of William Timewell at Wood, paid 13/4d to have four members of her family commemorated ‘a pon the luger [ledger] of the churche to be prayed for every Palme Sunday', but their names do not occur in this list of Sir Christopher's.4 In any case, the surviving list, carefully copied with its roll-call of wardens and benefactions, was quite clearly intended in the first place for the eye, rather than the ear:

Nota bene: Memorandum that here after schall ye see and knoo how this church was prevaylyd by the dethe of all these persons that here after ys expressyd by name: the wyche all and syngeler geftis was gevyn and be quevyd unto the churche syn y Sir Christopher Trychay was made vicar here … cuius anime propicietur Deus anime orate.5

Nota bene: Memorandum that hereafter shall ye see and know how this church was prevailed by the death of all these persons that hereafter is expressed by name: the which all and singular gifts was given and bequeathed unto the church since I Sir Chrstopher Trychay was made vicar here, … on whose souls pray God to be merciful.

The gifts and bequests for each of the twenty years covered by the list are introduced formulaically, each year identified both by its date and by the names of the High Wardens in office at the time, the gifts therefore located both in public time and Morebath time:

Anno Domini 1520 John Hucly and Richard Webber was hye Wardyns of this church: and how the church was prevaylyd by there Wardyng scheppe and by there tyme now schall ye see.

Anno Domini 1520 John Hukeley and Richard Webber was High Wardens of this church, and how the church was prevailed by their Wardenship and by their time now shall ye see

This was a record explicitly intended to last forever, for in it Sir Christopher refers to himself as dead and gone – ‘Dominus Christoferus Trychay condam [quondam] istius ecclesie vicarius [Sir Christopher Trychay, one-time vicar of this church]'.6 Yet it was also emphatically his list, compiled with the benefit of access to all the wardens' accounts, and priding itself on making good their omissions. So he details in the third person a series of his own gifts, adding that ‘all this for sayd he gave to this churche thof [though] hyt a pere not a pon the cownte of this ere'.7 Again, detailing a bequest from his friend, the Brushford chantry priest Sir Edward Nicoll, Sir Christopher informs the reader that the wardens have missed this one, perhaps because Sir Edward gave the money directly to Sir Christopher, ‘the whyche ys no thyng spokyn of a pon these men a cownt'.8 All the same, the list was clearly intended as part of the church book, an epitome and guide to the fuller records, designed to be read alongside them: as Sir Christopher comments,

and yf ye be yn any doute of any man ys gefth loke what ere that ye wyll have and loke a pon that a cownte and there schall ye a see playnly what proffyth this churche toke by the dethe of any man.9

All this suggests an acute awareness of the value of the written record, kept not merely to satisfy the requirements of external church authority, but as a crucial resource within the life of the parish, and one that gave its possessor a very concrete advantage in any dispute. Sir Christopher, as the scribe and custodian of the parish accounts, deployed this advantage in his own interest in 1547, when, among many other changes, the church floor was being re-tiled. As in every other Morebath project, Sir Christopher took a keen and active interest in this work, and he himself supplied and paid for half a hundred-weight of tiling stones from his own pocket. He proposed to repay himself for this outlay, he told the parish, by taking possession of four large slabs or steps (‘grystis') ‘that lay here be fore the quyre dore' (that revealing word ‘here', incidentally, places Sir Christopher exactly for us, standing in front of the chancel screen as he talks). If the parish objected, then they must repay him his money ‘and ye schall have your grystis stonys a gayn'. Conscious that some of his parishioners might resent this transaction as a trifle high-handed, he reminded them defensively that he himself had donated the slabs in the first place, and that he could give chapter and verse to prove it:

and yett y gave them to the churche furste and can tell who was Wardyn when ye fett them.10

Here the record is being drawn upon by the priest, simply as a matter of fact, to forestall friction in the parish. He ‘can tell' who was warden, and when he gave the stones, because it is all written down in his book. Many of the items in the book were plainly compiled with that purpose explicitly in mind. Tudor parishes were contentious places, for the parish, like the manor, was a forum in which the sometimes troublesome obligations of neighbourhood were prescribed and exacted. The communal life of Morebath, as we have seen, made heavy demands on its people. Parish officials had to enforce those obligations and, if they were flouted and persuasion failed, might refer the recalcitrant to external authority, the ecclesiastical or even the manor courts. Until the early Tudor period, most of those parochial obligations were religious, though the Tudor state increasingly harnessed the parish to its own purposes: the Lay Subsidy of 1523–4 was parish based and, as we shall see, secular demands were to be increasingly mediated through the parish structure.

But even before that process of secularisation manifests itself, the Morebath accounts have plenty of examples of the extreme care so small a community needed to take to ensure a fair distribution of responsibility, and of the wary compilation of records to prevent conflict, whether the issue was religious or secular. So in 1531 the priest compiled a guide to the collection of the ecclesiastical tax known as Peter's Pence, paid at the annual visitation and passed on eventually to the Pope. The document is brief, but, incidentally, provides us with our clearest and fullest guide to the number of placeholders and cottagers in Morebath. In it Sir Christopher notes that every ‘placeholder' in Morebath pays a halfpenny, every cottager a farthing, and that there would or would not be a surplus depending on whether Brockhole had a tenant, as it often did not.11 A longer list compiled the following year, not all of which has survived, shows the same concern with the fair distribution of parish burdens. In this list, however, the marking of internal boundaries, literal and metaphorical, is an explicit concern. The churchyard hedge (made, in the Devon manner, of stone walling as well as trees) was maintained by the parish, each of the farms and grazing grounds of the parish being responsible for maintaining a length of hedge proportionate to the size of the holding. By 1532 there had evidently been dispute about the matter, and it was decided to seek a formal order ‘by the a vissement of the vicar and of hys paryssyng' [by the advice of the vicar and his parish], which was duly entered in the church book and formally signed by the priest – his only surviving signature –

Robert Rumbelow for priers hay he makyth a xi fote

John Don he makyth a xj fotte

John Norman at Court he makyth a xj fotte now bytt he never made none be fore …

Thomas Rumbelow for hys home place he makyth a xj fotte and a xj fotte more for Bollyn

All Hawcrige downe makyth a xj fotte

Robert Rumbelow for Priors Hay maketh eleven foot.

John Don he maketh eleven foot

John Norman at Court he maketh eleven foot now, but he never made none before.

Thomas Rumbelow for his home place he maketh eleven foot and eleven foot more for Bollyn

All Hawkridge Down maketh eleven foot

Sir Christopher concluded this detailed entry with a liturgical flourish, carefully emphasising the informal and peaceable harmony that underlay this formal exercise in the demarcation of boundaries:

And thus ys the churche hage made from the yeste churche stylle to the west churche style: how bytt there ys more ground yn this for sayd space a lytyll more than the mesure and that ys made amonggis them pesabylly and under this manner this churche yerde ys closyd and schalbe fro thense: in seculum.12

And thus is the church hedge made from the east church style to the west church style. Howbeit there is more ground in this aforesaid space a little more than the measure and that is made amongst them peacably and under this manner this churchyard is closed and shall be from thence, for ever.

As Sir Christopher's choice of language suggests, the maintenance of the churchyard hedge was plainly a religious obligation, and in itself a powerful expression of the symbolic role of the parish church, the point of convergence in a community where fences and boundaries were important to the preservation of peace: good fences made good neighbours.

These religious dispositions found a close secular parallel in the course of the following year, in the record of two ‘setts' or formal levies, imposed on all the tenants of the manor of Morebath to recover ‘wold dettis', in one of which the parish sought to defend itself from external attack.13 The debts concerned were complicated, but both involved the parish's liability for the repair of the two bridges that linked them with the outside world, at Exebridge, where the maintenance costs were shared with the Somerset parish of Brushford, and at Hukeley bridge, where the costs were shared with the Devon parish of Bampton.14 As these and many subsequent references to the upkeep of the bridges make clear, the responsibility for maintaining them fell squarely on the Manor of Morebath, but was passed on to the tenants of the manor: for this reason, the few cottagers who were not tenants are invariably explicitly exempted from the setts made for this purpose. The money was collected by the tithing man, with payments calculated, as in the case of the churchyard hedge, on the size of land holdings. The money was handed over to the Four Men, who then dispensed it ‘to help to pay the demaundis'.

The Exebridge sett was comparatively straightforward, though some of the ‘wold dettis' concerned are said, rather improbably, to have been incurred ‘16 ere a gon' [16 years ago].15 The collection was designed to recompense parishioners who had ‘ledde out' money on behalf of the parish, and for that purpose to extract contributions from others who had been ‘be hynd at Exebridge'. Back payments were demanded from everyone so identified – ‘for lak of hys plow at Exbrige'.

The other sett ‘made this laste ere' (Sir Christopher's note was made in the early summer of 1533)16 reveals the parish struggling, probably unsuccessfully, to resist demands for the repair of Hukeley bridge triggered by a new piece of Tudor legislation. In its 1531/2 session, Henry VIII's Reformation Parliament passed ‘A Generall Acte concernynge Commissions of Sewers', a statute designed to rectify the neglect of waterways and sea defences, and to ensure also the repair of ruinous bridges.17 The Commissioners had power ‘to taxe assesse charge distreyne and punysshe' those liable for the maintenance of neglected bridges and waterways. Liability was to be established by enquiry from ‘honest and lawful men of the shire', and in the case of repairs charged on land, allocated ‘after the quantity of … landes, tenementes and rentes' held by those liable. The Commissioners were empowered to commandeer ‘as manny cartes, horses oxen beastes and other instrumentes necessary … and as many trees, woddes underwoodes and tymber' as were needed for the work; they could also requisition the services of local workmen.

The implementation of this statute evidently resulted in a claim against Morebath for Hukeley bridge. In attempting to resist it, Morebath's leading men became embroiled in an expensive and time-consuming series of visits to Bampton and Exeter. Both the Vicar and Thomas Norman, one of the Four Men, were involved in a series of negotiations at Bampton, while another of the Four Men, John at Courte, together with the Tithingman for that year, Thomas Borrage, and two more parish stalwarts, Harry Hurley and Richard Raw, rode backwards and forwards to Exeter ‘at on tyme and at a nother', to make representations before the Commissioners. The Commissioners evidently found against the parish, however, and distrained parish property to pay for repairing the bridge, for Morebath now instructed a lawyer to take out a ‘writ of replevin' in the county court to recover their goods. The lawyer in question, Roger Yorke, serjeant at law, was one of the most senior men in the profession. He was Exeter born, but since his marriage to Eleanor Lovell in c.1520 primarily based at Wellington in Somerset, only fifteen miles from Morebath. So distinguished a lawyer is most unlikely to have needed or sought the 12d Morebath paid him ‘at the delyveryng of the replevy at Exceter for Hucly Brige' in the way of ordinary business, and his acting for them must reflect prior acquaintance from another context.18 To discover the outcome, Harry Hurley was sent to consult the ‘schere boke [shire book] at Exceter to kno whether the schere dyd passe a gayn us or noo for Hucly Bridge'. The result is unclear from Sir Christopher's record: Harry Hurley went yet again to Exeter to fetch ‘a quyttance', but this need not mean that they won their case – it could well have followed admission of liability and settlement of the debt by the parish. However that may be, what is certain is that most of those involved in these transactions, including the vicar, ended up out of pocket. The sums concerned were a matter of shillings and pence, not pounds, but all the same the Four Men ‘suryd' [assured] and repaid them a good deal less than their actual outlay, yet another example of the uncomfortable demands which the corporate life of the parish was liable to make on its members.19

This incident provides the first evidence in the accounts of the strain which the legislative action of the Tudor state might place on the internal workings of the parish: within five years the accelerating pace of Henry's religious revolution would begin to cut deep into the living tissue of Morebath's communal life. What is notable about these minor financial flurries in the early 1530s, however, is the language of moral responsibility and conscientious dispensation of justice in which the entry describing them is framed. Other Devon parishes entered setts and financial settlements into their records – there are lists of similar obligations at the beginning of the Kilmington churchwardens' book, for example20 – but everywhere else, these lists are merely that – brief records of the liability of each parishioner, retained for practical purposes. At Morebath, Sir Christopher, who was paid sixpence for writing the whole thing up, ensured that this routine record of a piece of parish business becomes something more, an elaborate expression of the values on which the parish's moral unity was founded. He insists on the whole transaction being the parish's property, its remainders ‘yn kepyng tyll the parysse doo call for hyt'. The transaction itself is of course reported with all his customary meticulous insistence on minute accountability, and special attention is paid to money gone astray in the tangle of business transacted by many hands. Characteristically, at this point Sir Christopher's reporting allows us to catch a momentary echo of the Four Men speaking:

ys for the vs [5/=] that Thomas Norman ressevyd of John at Courte … we can have no knolyge of how hyt ys bestowyd: and no more we can not of the xxd [20d] that Harry Hurlye ressevyd of John at Courte savyng only they sayth that they be stowyd hyt but they can not tell where a pon.21

as for the 5/= that Thomas Norman received of John at Court … we can have no knowledge of how it is bestowed: and no more we cannot of the 20d that Harry Hurley received of John at Court, saving only they say that they bestowed it but they cannot tell whereapon.

But above all, the entry is framed in the language of communal morality, of oath-bound fidelity, of conscience. The sett for Exebridge, he notes, was authorised by the manor court ‘the next court be fore medsomer day: s[w]orne a pon a boke'. Four parishioners were nominated

to sett the parysse connsonabylly and to sure every man ys axcion and to se every man content: by there oathe and after there consyens: with the advyssment of the vicar Sir Christopher Trychay and William Tymewell at Wode: by mydsomer day every man to be contentyd and payd after the conssiens of these for sayd men a pon a grett payne.22

to sett the parish conscientiously and to ensure every man his exaction, and to see every man content by their oath and after their conscience: with the advice of the vicar Sir Christopher Trychay, and William Timewell at Wood; by midsummer day every man to be contented and paid after the conscience of these aforesaid men under a great penalty.

The not-so-subtle hint of menace there, with the Exebridge settlement made ‘a pon a grett payne', alerts us to the fact that the peace of Morebath depended on more than the bonds of good will and good neighbourhood. However united the parish might be against external threat, its internal harmony was both fragile and in need of enforcement. Secular responsibilities needed the sanction of law as well as the moral and religious enhancement bestowed by the involvement of the priest – in itself a striking testimony to the interweaving at Morebath of material and spiritual values – and the deployment of the language of obligation and conscience. By the same token, religious responsibilities also needed all the secular reinforcement they could get. The boundaries between matters of the soul and of the body in Morebath were loosely drawn. This emerges from a poignant entry in the accounts for 1531, when Richard Hukeley completed a bequest made by his recently deceased daughter Joan for a candlestick of five lights to burn before the image of the Virgin. Joan Hukeley's bequest did not cover the full cost of the new candlestick, and so her father paid the rest. He did so, however, not simply out of paternal piety for a dead daughter, but with an additional ulterior motive which strikes the squeamish modern reader as shockingly mercenary. The parish, it seemed, owed Hukeley money for expenses incurred on their behalf for work on the railing of Exebridge, and he hoped that his bounty towards the altar of Our Lady might encourage the parishioners to settle this debt. And so, the priest explains, he gave this money in his daughter's memory, ‘by cause you schuld se the soner that he mayth be contendyd for the rayling of Exbryge'.23

That characteristic Tudor interweaving of sentiment and savvy, the personal and the public, and the tendency for sacred and secular to converge at Morebath, emerge very clearly in the prolonged disputes surrounding the payment and duties of their parish clerk, which dribbled on through the 1530s and almost brought the parish to blows in the spring of 1537. The office of parish clerk was essential to the running of any parish church. The clerk was a paid official who assisted the priest in the liturgy by saying or singing the responses and by reading the epistle at Mass (so he needed a degree of Latin literacy, and some musical ability). He helped prepare vestments, vessels, books, lights and altars for services (a responsibility normally shared with the wardens). He brought the ‘pax-brede' round to be kissed at the peace ceremony of the mass, and he carried and distributed through the parish the holy water which was valued as a powerful and popular sacramental, capable of repelling evil and bringing blessing on men, beasts and crops. In many parishes the clerk was named for this aspect of his duties the ‘holy water clerk', and payment of his wages was linked to particular occasions in the year, like Easter, when he came with holy water to parishioners' houses.24

Canon law required that the clerk should be paid by the parish but chosen by the priest, and though one aspect or another of this stipulation was often contested, it was in fact the arrangement followed at Morebath.25 The clerk was thus a parish official, answerable to the people who paid his wages, often wearing a uniform, as he did at Morebath, the parish ‘livery'. He was also, however, the priest's right-hand-man, and, since the priest appointed him, usually also the priest's client, whose job depended on the priest's good will. At Sir Christopher's death in 1574, the current clerk had a son called Christopher, to whom the priest left a small legacy. He was probably another godson, further indication of the close links between priest and clerk.26 Appointment to the clerkship was therefore a valuable piece of clerical patronage. In the 1550s, the parish clerk of Morebath was Sir Christopher's own nephew, Lewis and Joan Trychay's son, a married man for whom the clerkship was presumably his main source of income, and, since the clerk was also called Christopher Trychay, once again very likely the priest's godson.27

In 1531, trouble arose at Morebath over the payment of the clerk's wages. Like so much else in Morebath's economy, those wages were calculated and paid in kind, the clerk collecting corn from every household, a lesser quantity from the cottagers, but no one exempt. The fluctuation in value that arises with any payment in kind was a potential source of conflict, and there seems to have been argument about a number of issues – how much the clerk was entitled to claim from each parishioner, when he could demand it, and what was to be done if the household concerned had had a bad or late harvest, or the grain was somehow spoiled. These disputes came to a head at Michaelmas 1531, when an unspecified number of parishioners reneged on the clerk's wages, and ‘this parysse they coude not a gre for a clerke by cause the clerke cudde not have hys duty'.28 Sir Christopher refused to appoint a clerk unless the parish would securely guarantee his wages, and it was decided to settle the matter by electing five men who with the Vicar would give a ruling on ‘the order of this clerke scheppe'. When ‘at laste the Vicar and the five men were … agreyd', the settlement was a comprehensive one, and the priest at his most expansive in recording it. In addition to his liturgical duties, too well understood to be specified, the clerk was to keep the church key and one of the church's chalices. He was to be responsible for locking the church. Evidently there had been trouble about security, with parishioners hanging about the building after services and then leaving the door unlocked all night. Sir Christopher's note at this point becomes positively prolix, suggesting some degree of exasperation; in the process he allows us a fascinating glimpse of the use of their church building by the people of Morebath: are the lingerers he describes praying, gossiping, sleeping? The parish church belonged emphatically to the parishioners, and so the clerk, it seems, had no power to evict anyone from the building. He must lock the church half an hour after the end of the last service of the day, when he was nevertheless to

knoke the churche dore and yff there be any perssons with yn the churche … and yff they wyll not cum forthe then by and by but they wyll tary styll with yn the churche where a pon at laste perventure when they cum forthe they lett stond oppe the churche dore all the nyghth after and yff any suche fortune there be where by the churche doo take any hurte, the payne and the iupardy schall rest to them and not to the clerke that doo remayne yn the churche after warde the clerke hath knokkyd the church dore …

knock on the church door and if there be any persons within the church … and if they will not come forth then by and by, but they will tarry still within the church whereupon at last peradventure when they come forth they let stand open the church door all the night after and if any such fortune there be whereby the church do take any hurt, the penalty and the jeopardy shall rest to them and not to the clerk that do remain in the church afterward the clerk hath knocked the church door …

In return for all this, the clerk was to be paid a penny a quarter by every household, and in addition was to have a ‘steche' or bundle of sheaves from every householder, payable on demand. Cottagers or those with no corn could commute this obligation for a cash payment. The collection of the clerk's corn had been at the root of the previous disputes, ‘because besenys hath byn oftyn tymys yn payment of the steche yn tymys paste'. The Five Men and the priest therefore laid down that the clerk was to have his ‘hyr mete', the quarterly penny per household, at Easter, and that he should send for his corn when it was ready, presumably after harvest time. Parishioners whose corn was not ready when the clerk sent for it were to keep it for him until he came again: if the corn was damaged or diminished, the clerk could claim cash in its stead, to the value of half a bushel of rye. The Five Men agreed to underwrite the clerk's wages in case of any dispute: and so, as Sir Christopher recorded,

now a pon all these poyntis ys the Vicar and these five men full a greyd and these five men have promyssed un to the Vicar substanssially that they wyll see the clerk truly payd of all such dutis as ys expryssyd before with out any trobyll or vexacion.

now upon all these points is the vicar and these Five Men full agreed and these Five Men have promised unto the vicar substantially that they will see the clerk truly paid of all such duties as is expressed before without any trouble or vexation.

And there, Sir Christopher hoped, ‘trobyll and vexacion' would cease. Entering the record into the church book, he headed it with a note which indicated that he believed that this settlement would outlast him: ‘anno domini 1531 at Mychelmas, Sir Christofer Trychay that tyme beyng Vicar here'.29

In fact the harmony established by the 1531 order lasted precisely five years, and then, 1536, spectacularly fell apart. At Michaelmas that year, once again parishioners began to cut up rough about the clerk's wages.30 William Leddon ‘wolde not pay hys steche of corne', William Scely and the (unnamed) tenant at Brockhole refused to pay the 4d in cash prescribed for householders who had no corn for the clerk. Two cottagers at Exebridge, John Don and John Nicoll, were up to date with payment of the 2d prescribed for a cottager with no corn, but they were in arrears with their 1d quarterly payments.

There was very possibly an element of social tension in all this. At least four of the five recalcitrant parishioners were certainly poor men, all of them, except the tenant of Brockhole, being cottagers, on whom the prescribed cash payments to the clerk in lieu of corn may have fallen particularly heavily, and who may well have resented paying the same quarterly charge of a penny as the wealthier men of the parish. William Scely in particular was to have something of a history of awkwardness over the financial demands made by the parish. Three years on, when he was warden of the church sheep, he would antagonise the priest and delay the annual sheep count for six months because the parish owed him money he had laid out on the repair of Exebridge. Scely held on to 4s all but 1d from the funds of the sheep store, refusing to balance his books or present an account until he was reimbursed, ‘and so keppt our mony tyll he was payd'.31 3/11d is a relatively small sum to warrant so large and aggressive a disruption of the parish calendar, and the priest quite evidently thought so: the incident probably tells us as much about Scely's personality as his poverty. At any rate, when he died in office as High Warden in the fraught year of Reformation 1548, his widow would continue the family tradition for awkwardness by unilaterally ‘[selling] away the church goods with out commission', thereby evoking from Sir Christopher one of his bitterest expressions of outrage.32

However that may be, with five out of Morebath's thirty-three householders in one way or another withholding the clerk's wages, the priest considered that something must be done. And so for

lacke of tru payment the vicar that fownde the parysse a suffycyent clerke before that tyme wolde not mell [meddle] no more with the clerkscheppe by cawse he cowd not have hys duty truly payd with out dysplesir takyn of hys paryssyn.

lack of true payment the vicar, that found the parish a sufficient clerk before that time, would not meddle no more with the clerkship, because he could not have his dues paid without displeasure taken of his parishioners.

At Christmas 1536 he gave the clerk three month's notice,

desyryng the parysse hole to be contendyd to provyd him a new clerk agayn our Lady at lent then follyng for he wolde mell no more with hyt.

desiring the whole parish to be contented to provide him with a new clerk before Our Lady at Lent then following, for he would meddle no more with it.

By dumping this problem in the parish's lap at Lady Day, Sir Christopher was playing his cards skilfully. The deadline he had set, Lady Day (25 March 1537) was of course one of the quarter days, and a usual time for starting or ending contracts. But it fell that year, as the priest must certainly have known, on Palm Sunday, the day of the parish's annual commemoration of dead benefactors but also the start of Holy Week, and, he notes, ‘the besy tyme of Ester', inaugurating two weeks of the most elaborate liturgical celebrations of the year, which made a clerk's services absolutely indispensable. The ‘parysse universall' therefore begged him to continue the clerk's services till ‘lytyll Easter Day', that is, the Sunday after Easter, pending a proper settlement. Trychay duly did so, but once more ‘when that day was come, communicacion was hadd, and they coude not a gre a bowt a clerk'.

An opportunity to bring outside pressure to bear on this fraught situation now presented itself. By a coincidence, the parish was due to send its representatives to an episcopal visitation at Uplowman, near Tiverton, on Thursday of that week. The Vicar, the senior warden Harry Hurley, and Thomas Rumbelow, standing in for the village smith, John Hukeley, who was second warden that year, together with John Norman at Court, one of the Four Men, duly presented themselves before the bishop's official. The parish, presumably at Sir Christopher's prompting, had already determined to ask for authority for four ‘honyst men chosyn by the hole parysse' (whom they had already elected), to ‘rule and governe the parysse yn all caussis concernyng the welthe of the churche'. With the added urgency of this new complaint, the official granted the order. It was written on the back of the loose-leaf copy of the High Wardens' account presented for routine inspection, and duly sealed with the official's seal, and later entered into the account book (though it has not survived). The vicar and wardens were then authorised to ‘goo home and take and desyre Mr John Sydenham un to them', so that he and the duly elected four men could determine the matter of the clerkship, which ‘the vicar and the parysse schalbe contendyd withal'.

The inclusion in this group of John Sydenham, son of Sir Christopher's friend Edward Sydenham of Dulverton, and so a gentleman from quite another county and diocese, is striking. He was probably chosen not merely as a representative of the nearest gentry household, and a friend of the priest, but because two of the Exebridge cottagers refusing quarterage to the clerk were Sydenham tenants. At any rate, he accepted the invitation, and a ‘fresse day … of communicacion' was set for Sunday 22 April, the eve of St George, the parish's patronal festival.

Once again, however, the ‘day of communication' did not resolve the dispute. Mr Sydenham duly appeared, as did the bishop's summoner, Matthew; together, like twin representatives of God and Mammon, Sydenham and the summoner quizzed the parishioners individually ‘by name' whether they were contented to obey the official's ruling, elect four men to determine the matter with Sydenham, and abide by the outcome. Anxious to emphasize the thoroughness of the consultation, Sir Christopher notes their precise words – ‘now how say ye to this, ye parysse, they sayd'. The parishioners duly elected William Timewell at Wood, John Norman at Court, Richard Hukeley and Robert Timewell at Hayne, parish heavyweights with a record of service in the stores, the high wardenship, and the government of the church stock. These were in fact the men already nominated in the official's mandate, ‘the same selfe persons that were chosen a fore and admyttyd by the ordinary to rule and governe the churche gooddis as ys expressyd a pon the bake of a cownte and under the ordinaris auctorite'. The parishioners were then quizzed again, householder by householder, whether they would agree to be bound by whatever the Four Men and Sydenham decided. Twenty-six consented, but ‘there was 5 men of the other parte that wolde not be orderyd by no man'. Sir Christopher names four of the five:33 they were by no means parish marginals or malcontents, nor poor men smarting under excessive demands. They included parish leaders like Thomas Norman, one of the Five Men responsible for the original order upon the clerkship in 1531 and one of those elected to ‘sett the parysse conssonabylly' for old debt in 1532.34 Another of them, John Timewell at Burston, had recently served as both St Anthony's warden and Our Lady's warden, a third, Richard Webber, had been High Warden in 1533, and if, as seems likely, the unnamed fifth man was William Leddon, the dissidents also included one of the previous year's high wardens. The meeting therefore dissolved with no agreement, and at ‘evensong follyng', first vespers of St George's day, there was no clerk to help the priest, ‘nother the morrow that was sent iorge ys day'.

The lack of the clerk on the church's patronal festival was to poison an already harrowing human situtation. One of the poorest men in the parish was the Exebridge cottager, Marke. His wife had just given birth to twins, both of whom however died soon after baptism. Such children were known as ‘crysom children', from the holy oil of chrism used in the baptismal rite and the fact that at death they were still wearing the ‘crysom' cloth bound round the child's brow over the spot anointed by the priest and worn for a week thereafter. Poignantly, the account of the Alms Light for 1537, kept that year by the priest's brother Lewis, includes the poor man's payment of a penny from Marke, ‘for the occupyeng of the almys lyghth by the deth of hys 2 crisimmers'.35

As it happened, Sir Christopher had arranged to celebrate a requiem mass for Marke's children on the morning of St George's day. When he arrived at the church that morning with the grieving family, still raw from the recent deaths, however, they found the door locked, there was no chalice, and no one present was able to make the responses or serve the Mass. Marke therefore was obliged ‘to goo to John at Courtis [one of the Four Men] to fett the churche dore key and the challys and also he fett the wolde John Waterus [a former parish clerk] to helppe the vicar to mas be fore he coud have any mas sayd for hys chyld: and all was for lacke of a clerke'.

Morebath church was dedicated to St George, and St George's day was in any case one of the festa ferianda, universally observed religious holidays when no work was done.36 That year the whole parish was due to go to the house of William at Timewell for the betrothal of his daughter Margaret to William Taylor, the day presumably chosen because everyone would be at leisure to join the party. But the distressing scene at the church ensured that this was a doomed occasion. ‘All that day', the priest reported, ‘we resonyd schamfully a bout our clerkscheppe.' William Leddon, one of the men whose refusal to pay the clerk's corn had precipitated the crisis, was also at the betrothal, and the bereaved father, Marke, nerves ragged from the fiasco over his children's requiem that morning, confronted Leddon, so that they ‘ware a most by the eris [ears] for the same causse'. The resulting scene and the arguments that followed were spectacular enough to persuade everyone that something had to be done to resolve the situation, ‘so yn conclusion the parysse hole concludyd there and sayd lett us have a fresse day of communicacion and we wolle be orderyd every on of us'.

The priest therefore re-appointed the clerk on a temporary basis, and a new parish meeting was fixed for the next Sunday but one, the Sunday before Rogation week. This date must have had a special resonance in the circumstances, and was perhaps chosen deliberately, since Rogationtide was a traditional time for the settlement of parish disputes. One of its principal ritual and symbolic themes was the restoration of charity and harmony in the community.37

In the meantime, the manorial court of Morebath met. Barlinch Priory had been dissolved the previous year,38 and the manor, together with the rectorial tithes of Morebath and the right of presentation to the vicarage, would pass in May 1538 to a notable soldier and courtier, Sir John Wallop: from then on the priest refers to the tenants of the manor as ‘Mr Wallop's tenants'. From March 1537, however, the manor and rectory of Morebath were let to the Somerset landowner Hugh Paulet,39 whom the priest describes in several places as ‘Master' to the manorial bailey, Hugh Dysse – Paulet was, therefore, effectively the parish's principal landlord. In the week after the confrontation at poor Margaret Timewell's betrothal, ‘Mr Hu Powlett kept courte at Morebath', accompanied by another gentleman with property in the parish, Mr Hugh Stucley, whose family owned the land grazed by the Sydenhams on Hawkridge Down.40

To the moral pressure of the parish and the ecclesiastical authority of the bishop's official and the summoner, Paulet now added a secular landlord's muscle and the weight of the manor court. He ‘exortyd these for sayd 5 perssons and so dyde Mr Hugh Stycly also that they should be contendyd to be orderyd as the moste parte of the parysse ware: and yf they wolde not he wolde ordor them he sayd.' Paulet therefore issued a formal citation into the court, to be held in menace ‘to cyte all such perssons as wold not be orderyd by Mr Sydenham and by the 4 men'.41

In the event, there was no need to implement this citation. On the appointed Sunday, Sydenham and three of the Four Men (Robert at Hayne was ill), backed by Hugh Dysse the bailey representing Paulet and Mathew the summoner on behalf of the diocese, were able to settle the dispute. Though two of the recalcitrant parishioners (the cottagers William Leddon and William Scely) had absented themselves and Margaret Timewell's father William was also missing, the rest of the parish were present and ‘then was the parysse syngulerly demanndyd a gayn by name' whether they would ‘bide by the ordor' of Sydenham and the Three Men, and ‘they said ye[a] all that were yn the churche that tyme'.

The order made ‘to this entent to have the more unite and pece a mongg us and to have the church the better served' spelled out in greater detail than ever the arrangements for the clerk's wages, and established a new machinery for recovering them if parishioners proved troublesome. The clerk was to have a steche of ‘clene corn' from every household, or, where there was none, a steche of oats. Households with no corn to give paid three pence instead, cottagers paid two pence. If the clerk was dissatisfied with the quality of the grain offered, one of the Four Men would inspect it and decide whether it was ‘sufficient'. If not, the clerk was to be allowed ‘with out any besenys' to fetch a better from one of two guarantors or sureties, Richard Hukeley for the western part of the parish, John at Court for the eastern, appointed by the parish to see that the clerk should be paid ‘without any trobyll or vexacion'. If any ‘froward felow' should refuse payment, and the sureties had to pay the corn on their behalf, then the parish undertook to ‘were them harmlis' and make good their loss.

In addition to his corn, the clerk was to have a penny quarterly from every household, and to be paid a fee of tuppence at every wedding, and every funeral and month's mind ‘song by note'. Once a year he was to go about the parish with holy water ‘when menne have schorne there scheppe', to gather wool from each household, ‘to make him cotte to goo yn the paryssen ys livery'. His duties were briefly specified – to keep and hide the church door key ‘as he wyll doo hys one', to keep the chalice, and to help the wardens make up the vestments and dress the altars. That year, to make good the ‘losyn of hys duty yn tymys paste' the parish ‘schall helppe to drenke him a cost of ale' at Trinity Sunday, at which it was stipulated that all the dissident parishioners must be present, and thereafter there was to be ‘a cost of ale' drunk in the church house at Easter for the clerk's benefit. The settlement was duly noted ‘here a pon this cownte boke to testyfy truly the clerke ys duty and our award to a voyd all other unconveniens'.42

1537 was a fraught year in Morebath, with signs in the accounts of ragged nerves and parish tensions, quite apart from the strains created by the clerkship. There was trouble over the Young Men's store, when one of the elected wardens, Edward Norman of Loyton, ‘wolde not take this Wardyn scheppe a pon him', and a substitute had to be found. Later in the year Sir Christopher himself antagonised some of his parishioners by making an unauthorised payment of 20/= ‘agaynst the parysse wyll' to John Paynter, then at work on a new High Cross for the church. The priest was to end up a pound out of pocket because ‘some of you gurgyd [grudged] at hyt', and in that year of conflicts he thought it prudent to let the matter pass, accept that he had put himself in the wrong, and donate the money to one of the other church funds.43

But the affair of the clerkship brings into sharp focus the extraordinary complexity of the concept of community in Morebath, and the interweaving of religious and secular considerations in the pursuit of peace. It discloses to us a small rural community in which the non-cooperation of a handful of poor men could paralyse the parish's decision-making and smooth working, and in which consensus, however achieved, rather than majority rule, was felt to be the essential basis for collective action. It discloses, too, a community in which economic division, though present, was not the fundamental principle of social organisation or hierarchy. What may have begun as a protest by some of Morebath's poorer parishioners against a burden they perceived as falling harder on them than on others, had certainly broadened beyond any purely financial basis, to include some of the more substantial farmers. It had become a dispute about order, and the willingness of individuals to ‘be orderyd as the moste parte of the parysse ware'. The dispute had begun within the parish church, and it focussed on the payment of a key figure in the liturgy of that church, the priest's right-hand man. But it invaded one of the most domestic moments of parochial sociability, Margaret Timewell's betrothal, and it extended itself first to the ecclesiastical and then to the manor court. Parochial disorder found its liturgical counterpart in the disastrous requiem for Marke's chrisimers, and it was resolved by a formal meeting of the parish in the church between Mass and evensong on Rogation Sunday, a settlement in which the parish's landlords and the representative of the bishop lent their weight. The restoration of ‘unite and pece a mongg us' was celebrated in the church ale house, at a feast of reconciliation at which the dissident parishioners, those froward fellows whose action had disrupted the peace of the parish in the first place, were ordered to be present, and which doubled up as a fund-raising exercise to make reparation to the clerk for the financial loss inflicted on him by the dispute.

Like everything else at Morebath, we view the whole incident through the priest's eyes. His account of this ‘fresse warde a pon the clerk scheppe', the longest single item in the book, is by no means a neutral document. The distress caused by the delays before the requiem for Marke's children and the father's frantic searching through the parish for key and chalice and someone to serve ‘be fore he coud have any mas sayd for hys chyld', the acrimonious disruption of Margaret Timewell's betrothal, the shamefulness of division in a small community set ‘a most by the eris' by its inability to resolve its differences – all are reflected to us through his sensibility, and it is Sir Christopher's dismay we feel. His narrative is marked by easily recognisable clerical concerns – his elaborate protestations that he will ‘mell no more' with an issue which might incur the ‘displeasure of his parishioners', his emphasis on the official's seal and the anxiety this represents to underpin the community's self-regulation with the authority of the bishop, the religious language of ‘unite and pece a mongg us'. But the events he describes, and the community voices and relationships his account displays so circumstantially, bear all the marks of authenticity. 1537 was the last year in which Morebath's pre-Reformation pieties, and the complex social arrangements which underlay them, would remain comparatively undisturbed. Sir Christopher's account of the rise and resolution of these conflicts allows us to observe the dynamics of a world at the last possible moment before it underwent dramatic and far-reaching change. As a working model of the inter-penetration of secular and religious values and institutions in pre-Reformation England, the clerkship dispute at Morebath would be hard to better.

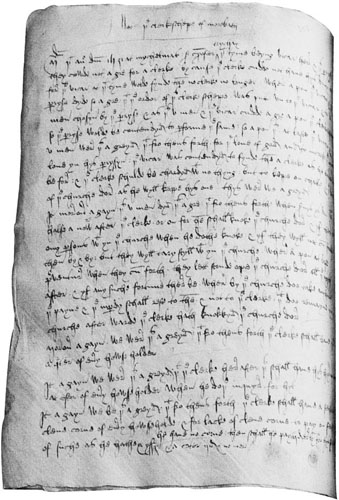

*Sir Christopher's account of the beginning of the disputes over the wages of Morebath's parish clerk [Binney 33–4 / Ms 356–7]