by Susan Donoghue, V.M.D., D.A.C.V.N., and Philippe de Vosjoli

Bearded dragons consume a wide variety of animal and plant foods throughout their lives. Studies of the stomach contents of wild bearded dragons in Australia showed that when young, these lizards eat about 50 percent live food and 50 percent plants, and when mature, they eat mostly (65–90 percent) plant matter. Observations of thousands of dragons in breeding facilities suggest that similar food preferences occur when these lizards are in captivity. Plan to feed your dragon proportionally more live, moving prey when it is young, and offer relatively more vegetarian fare when it reaches middle and old age.

It is our experience that very young bearded dragons really do need live prey, despite what one may hear or read to the contrary. Without live food, there is a high risk of stunting growth and malnutrition, and even death from starvation. Moreover, baby dragons housed together will cannibalize each other, nipping off toes and tail tips if hungry and deprived of adequate amounts of live prey. If you want a bearded dragon as a pet but won’t accept live prey in the house, we suggest that you purchase an older dragon. Young adults and mature dragons can be maintained without live prey, though they greatly enjoy, and we suspect would prefer, occasionally feeding on live food.

The enthusiastic and eclectic appetites of bearded dragons give owners an opportunity to interact with their pets and bring much enjoyment to both species. Food treats can be used as rewards and to attract the attention of a pet dragon. Many a dragon happily bounds up to an owner when snacks are in hand, and food often serves as the strongest bond between dragon and owner. Dragons are nutritionally robust, handling many food treats and careful diet changes with minimal or easily resolved perturbation of their digestive tracts. Sound diets for dragons have builtin nutritional flexibility that allows for treats and snacks without creating imbalances. We provide guidelines for sound diets and appropriate snacks later in this chapter.

Hand-feeding is a powerful tool for establishing a pet/owner relationship.

Bearded dragons are usually fed commercially-bred invertebrates such as crickets (Acheta domestica), mealworms (Tenebrio molitor), giant mealworms (Tenebrio molitor), superworms (Zophobus morio), wax worms (Galleria mellonella), and juvenile Madagascar hissing cockroaches (Gromphodorhina portentos). These are available for sale in many pet shops and by mail order.

Bearded dragons cannot be maintained well on flying insects, such as houseflies, which easily evade the dragons. Although dragons may eat earthworms and other garden worms, these prey aren’t commonly taken as food.

Larger bearded dragons do not hesitate to eat small lizards and in fact appear to relish them. In captivity, adults also feed on juvenile (pink to fuzzy) mice. These can be a useful part of a varied diet for larger dragons, providing nutrients such as calcium and many vitamins and trace minerals that are not readily available from invertebrates and salads. Supplementation is unnecessary. Vertebrate prey require balanced diets and water if kept for more than a day.

Vegetarian foods are available in local markets. Greens, vegetables, and fruits can be offered in appropriate-sized pieces. Generally, finely-chopped produce is accepted best. Plants from fields and lawns that haven’t been treated with pesticides and herbicides can be fed, too. Leaves and blossoms from clover, dandelion, and mustard are especially relished. Other treats include many species of grasses and petals from blossoms of roses, hibiscus, and calendula.

Commercial diets for bearded dragons are primarily dry pelleted foods. These products may be marketed specifically for bearded dragons or for other pets. Bearded dragons have been raised and maintained successfully when part of their diet has consisted of commercial dry foods formulated and marketed for cats and dogs, and also for other species such as iguanas, tortoises, and cage birds. It is our opinion that no commercial diet, whether marketed for bearded dragons or for other animals, should be the only food offered to bearded dragons. Advantages and drawbacks of commercial diets are discussed later in this chapter.

Bearded dragons require supplementation with a powdered vitamin/mineral supplement and calcium to make up for deficiencies and high phosphorus levels in commercially produced insects and produce. Reptile supplements are now readily available in stores that sell reptile supplies. Because they vary widely in their formulations, you should carefully examine the labels for contents. Ideally, you should select a source of calcium such as calcium carbonate powder plus a supplement that contains vitamins and minerals including trace minerals. Only small amounts are required—just enough to lightly coat, or dust, insects and plant matter.

Offer high-quality, clean water that is free from contaminants. Generally, water that is safe for you is safe to give your bearded dragon. Most problems with water quality arise from a dragon fouling its water with feces or decomposing food. Be sure to clean the water container daily, and offer clean water at least daily or more often if needed.

Offer water in a shallow dish no more than half the lizard’s body height when at rest and wide enough to fit its entire body width. The water must be visible when the dragon is up on all fours. A dragon often enters its water dish and lowers its head to drink.

Bearded dragons (especially babies) are not the brightest lizards when it comes to recognizing water. Generally, they are attracted to the scintillating reflection of light on water droplets or a moving water surface. Because they are attracted to moving water, pouring or dripping water into a container often entices bearded dragons to enter and begin drinking. Spraying the sides of the habitat with water may prove particularly useful for watering babies who, as a rule, don’t readily recognize standing water. Dripping water on a bare enclosure floor using a rodent sipper water bottle is another method for tempting dragons to drink. To assure that your bearded dragons get enough water, a good backup method is to manually give them water with a plastic sipper water bottle, slowly squeezing the bottle so that droplets of water fall at the tip of each dragon’s snout.

If the above suggestions do not work, an alternative method is to provide no water container in the enclosure but instead remove the dragons and soak them in pans of shallow water two or three times a week.

Water is also obtained through diet. Insects and fresh salads contain about 60 percent and 85 percent water, respectively. Pellets contain only 10–12 percent water, so dragons fed only pellets need to receive enough water each day. Lack of water leads to dehydration and electrolyte disturbances, which seriously impact many organ systems.

All foods offered to bearded dragons should be wholesome and either fresh or carefully preserved. Crickets, mealworms, and other invertebrates need to be fed a balanced diet. Breeders have successfully fed them ground dog food, rodent chow, or poultry feed with fresh fruits, greens, and sliced fruit, but now diets specifically formulated to feed crickets are available. Balanced diets, when present in the guts of the insects, make up part of the nutrients absorbed by bearded dragons after prey are consumed. Wax worms need a special diet that includes glycerin, honey, ground cereals, and brewers yeast. Invertebrate enclosures should be cleaned routinely.

Vegetarian foods should be washed prior to feeding if herbicide or pesticide applications are likely. Produce from the market should be checked carefully for hazardous materials such as twist ties, bits of plastic, and rubber bands. These items can lead to life-threatening digestive problems. Remove sticky labels from the surfaces of apples, pears, and the like. Today’s frozen vegetables marketed for human consumption are well preserved with little loss of vitamins and other nutrients. These should be thawed before feeding.

Parts of produce intended for human consumption contain lower concentrations of herbicides and pesticides than those parts intended to be discarded and uneaten. Hence, exercise special caution when feeding produce considered inedible by humans, such as rinds from melon and kiwifruit.

The nutritional value of pellets and hay products deteriorates relatively rapidly from exposure to light, air, or heat. For example, levels of beta-carotene, a precursor of vita-min A, fall to less than 50 percent by six months after harvest, yet most commercial pellets and hay products don’t reach store shelves until at least several months after hay harvest. We select alfalfa- or clover-based products that still look green.

Supplements have limited shelf lives. Many vitamins decompose from exposure to light, air, and heat. Others are oxidized by contact with trace minerals. We recommend that you select products with expiration dates, and replace supplements at least every four months.

Calcium-Supplemented Dragons That Twitch Their Toes

FAQ: I set up my baby bearded dragons just right, or so I thought. They are in a room kept at about 80°F with a UV-B emitting bulb. They are fed twice daily with 1/4-inch crickets dusted with calcium and a general vitamin-mineral supplement. This week, a few started twitching, and my vet diagnosed them with calcium deficiency. Where did I go wrong?

Dietary problems arise as much from errors in husbandry as from diet per se. Years ago, we accidentally induced calcium deficiency in baby dragons kept like yours. The problem wasn’t with diet or supplementation but with light and heat. Dragons respond to a bright light and a basking spot that is warmer than the overall enclosure. Without stimulation from light, our baby dragons ate a less than optimal number of crickets and developed signs of calcium deficiency. Moreover, such signs don’t always have to be due to calcium. Deficiencies of magnesium and glucose can produce similar signs. Whenever you’re faced with a nutritional problem, check out husbandry too. For your case specifically, we suggest dropping the room temperature to about 70–75°F and adding a bright light that creates a basking spot of about 90°F. Make sure you retain a temperature gradient so that the dragons can select cooler temperatures, too.

Bearded dragons are active in the daytime and asleep at night. Thus you will want to offer your dragon the bulk of its food in the morning. This is especially important if you are away in the daytime and return home late when the dragon will be sleepy and less interested in eating. The second meal of the day should occur at least an hour or two prior to lights being turned off. Prey that are uneaten and roaming at night can stress or even bite your dragon. Roaming hungry crickets have been known to fatally wound baby dragons.

During winter shutdown, adult bearded dragons are inactive and may not feed at all. Do not force-feed them at this time. Once your bearded dragons are active again, return to the usual feeding schedule.

Bearded dragons are fed frequently when babies, usually two or three times daily. As dragons mature, feeding frequency declines gradually to once daily as young adults. As older adults, they can be fed daily or every other day.

Some successful breeders of bearded dragons offer water only three times weekly. Others maintain water around the clock. Which system is right for you? Bearded dragons evolved in the arid regions of inland Australia and are adapted to dry environments and limited water. Moreover, many of the foods we recommend for dragons, such as invertebrates and salads, contain water. Daily exposure to water is likely unnecessary under certain specific husbandry systems, especially for dragons kept outdoors. However, dragons maintained indoors, especially those in heated homes and those consuming dry pellet foods benefit from daily access to water. We recommend that all pet dragons kept indoors have access to clean water in shallow saucers.

As a general rule, bearded dragons are fed as many crickets as they can consume in one ten-minute feeding. Adult dragons can be maintained with constant access to invertebrates (during the day) if the prey are confined to a bowl and not free-roaming and creating stress for the dragons. Salads and commercial foods are also available during the day, removing any foods that might decompose at night. Supplements are added carefully to insects and salads, providing just a light coating.

As for size of live prey, bearded dragons almost never suffer from eating prey that are too small. But many dragons, especially babies, have died from eating prey that are too large. A general guideline is to feed crickets that are no longer than the width of the dragon’s head. For babies, that means feeding crickets that are just a week or two old and no more than 1/4-inch long.

Crickets and mealworms should be lightly coated with a vitamin-mineral supplement.

As dragons grow, other prey can be fed, but always follow the rule that the prey should be no longer than the width of the dragon’s head. Go easy on feeding prey with high chitin content, such as mealworms. However, our dragons relish hard-shelled beetles and we use May beetles and June bugs as treats for adults in early summer. These beetles are too large for juvenile dragons.

Most diets for bearded dragons require nutrient supplementation because few of the foods in their diets are nutritionally complete or balanced. Invertebrates (crickets, mealworms, superworms, wax worms) lack calcium because they have no skeleton and are deficient in several vitamins and trace minerals. Vegetarian foods (such as greens, carrots, bananas, etc.) are deficient in a variety of essential nutrients such as calcium and certain amino acids, fatty acids, and trace minerals.

Generally, baby bearded dragons require daily supplementation, and older animals need gradually decreasing rates of supplementation so that they are supplemented weekly or every other week.

The type and amount of supplementation needed by your dragon depends on many factors. For example, dragons housed outdoors with access to the ground obtain the vitamin D3 from basking in the sun and many trace minerals from access to soil, whereas those kept indoors would need these essential nutrients provided in their diet. We’ll cover the most common scenarios for supplementation in this chapter.

Help! My Dragon’s Having Convulsions!

FAQ: I bought a pair of baby bearded dragons a month ago. They’ve been eating great and growing rapidly. Suddenly, today I found one having convulsions and the other’s toes and feet are twitching. What should I do?

This scenario sounds like a classic case of calcium deficiency in baby dragons. Those babies eating the most and growing the fastest need the most calcium in order to support such rapid growth. Signs of calcium deficiency include tremors, twitching, seizures, and bloating. Give your dragons calcium immediately: we recommend a liquid form, such as Neo-Calglucon (manufactured by Sandoz and available in pharmacies), as the first step for babies that are twitching or having seizures. Consult a reptile veterinarian for dosage and administration. Next, evaluate husbandry and diet. Are your dragons exposed to ample UV-B from sunlight or special bulbs? In our experience, exposure to a reptile mercury vapor UV-B bulb in combination with orally administered calcium is highly efficient, causing improvement in as little as twenty-four hours in bearded dragons and other lizards that display the muscular tremors associated with calcium deficiency. Do they have a source of dietary calcium and dietary vitamin D3? You may need the help of a qualified veterinarian to correct the immediate problem of hypocalcemia and for advice on fixing the dragons’ husbandry and diet.

Calcium is critical for healthy bone growth in bearded dragons. You’ll want to feed your dragons foods high in calcium, but dragons need supplemental calcium as well, regardless of diet. (However, if you feed your dragons only balanced and complete dry pelleted diets then you don’t need to supplement.) Most supplements emphasizing vitamins and minerals fail to provide enough calcium to meet the needs of dragons. Thus, two types of supplements are often necessary: one containing vitamins and minerals (including a little calcium) and the other containing mainly calcium (such as calcium carbonate, bonemeal, and cuttlebone).

Dragons needing the most calcium are babies and egg-laying females. Appropriate rates of supplementation vary with the dragon’s age and size, housing (indoors or out), calorie intake, amount of calcium provided by the diet, and amounts of several other nutrients in the diet, including phosphorus and vitamin D3. Generally, baby dragons are supplemented with calcium daily or every second day, and rates decrease with increasing age and size.

Bearded dragons require 1–1.5 percent of the diet dry matter as calcium, and about 0.5–0.9 percent phosphorus. Attention is often given to the ratio of calcium to phosphorus in the diet. It should be in the range of 1:1 to 2:1 calcium:phosphorus (Ca:P). However, the amounts of dietary calcium and phosphorus are more important than the ratio. For example, if a diet contained only 0.4 percent calcium and 0.2 percent phosphorus, the Ca:P ratio would be 2:1 but the amounts are deficient and a dragon fed this diet would develop calcium deficiency.

Of the commonly available calcium supplements, calcium content is 40 percent in calcium carbonate, 38 percent in limestone, 18 percent in calcium lactate, and 9 percent in calcium gluconate. Calcium and phosphorus contents are 24 percent and 12 percent in bonemeal, and 24 percent and 18 percent in dicalcium phosphate.

Bearded dragons require vitamin D for a variety of functions, including the formation of strong bones by aiding the absorption of dietary calcium. Dietary vitamin D comes in two forms—vitamin D2 (ergocaciferol), which occurs in plants, and vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol), which occurs in animal tissue, especially liver. There is evidence that reptiles cannot utilize vitamin D2, so vitamin D3 is always recommended for bearded dragons. Basking lizards such as bearded dragons can also make vitamin D3 by exposing their skin to UV-B light rays from the sun or from special commercial lamps. We know of no scientific data demonstrating the relative value to dragons of vitamin D3 obtained from diet or from UV-B exposure.

Although some dragons seem to do well without dietary vitamin D if they live outdoors year-round, we recommend a source of dietary D3 for most bearded dragons, especially those living all or part of the year indoors. Vitamin D3 is listed on food labels as cholecalciferol, animal sterol, D-activated animal sterol, irradiated animal sterol, or vitamin D3. Don’t assume that the term “vitamin D” in the label ingredient list is actually D3, for it may be D2 and unusable by your dragon.

As with many nutrients, vitamin D is toxic when fed in excess. Toxicity most commonly occurs from overzealous supplementation with vitamin-mineral products. Toxicity also occurs from the ingestion of certain types of rat and mouse poisons. Signs of toxicity often involve multiple organ systems because of widespread soft-tissue calcification. The active form of vitamin D is made by a series of chemical transformations in liver and then kidney. Thus diseases of the liver or kidney will affect vitamin D metabolism and can lead to signs of deficiency or toxicity.

Disorders caused by too little or too much vitamin D, or diseases of the liver and kidney, which lead to secondary problems with vitamin D, require veterinary attention.

Newly hatched bearded dragons may take a day or two to begin eating. During this time, the baby receives needed nutrition from its own reserves, mostly through its resorbed yolk sac. The youngster should be housed in a small enough enclosure so that it can find its food and water.

Babies should be started on one- to two-week-old crickets and graduated to larger crickets as they grow older. Offer the baby dragon only a few live, small (about 1/8-inch) crickets. To determine appropriate cricket size, figure the crickets should have a length no greater than the width of the head of a bearded dragon. Offering a larger number of smaller prey promotes more efficient digestion than offering a smaller number of larger prey.

Greens and vegetables should be offered daily, finely chopped (left) for baby bearded dragons and coarsely chopped (right) for adults.

Observe the baby dragon to ensure that it is eating. Within a day or two of hatching, a baby dragon should be a lively feeder. Don’t overload the tank with crickets, which will stress the dragon. Loose crickets will crawl over the lizard and may bite it.

Crickets should be offered two to three times daily. Observe that the bearded dragon is eating and offer only enough crickets that can be eaten in one feeding (within about ten minutes).

Drinking water should be provided in shallow saucers; we use inverted plastic can covers. Very young hatchlings are often thirsty but can have trouble finding water in a large enclosure. Lightly misting the walls and enclosure furnishings or dripping water into a saucer can help baby dragons to begin drinking. The goal is to provide drinking water for the hatchlings, not to create a humid environment or standing puddles of water.

Crickets should be dusted once a day with a mixture of powdered calcium carbonate and a vitamin-mineral supplement. This is most easily accomplished by placing an allotment of crickets into a smooth-sided container from which they can’t escape, such as a glass jar or plastic pitcher, then adding an amount of supplement appropriate to the number of crickets to be fed out. As a rule of thumb, a small pinch of supplement will be adequate to coat the insects for feeding two to three baby dragons; for larger dragons figure a large pinch per animal or an eighth of a teaspoon for a trio. Then gently stir the container for a few seconds until the crickets are lightly coated with the supplement, and feed the crickets to your hungry dragon.

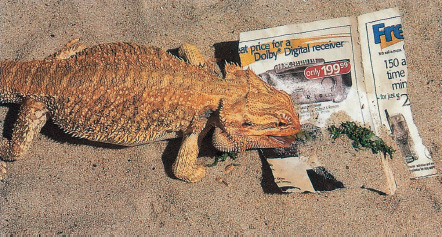

One of the pro-posed benefits of making veggies plentiful is to reduce intraspecies mutilations by curbing hunger. Photo by Roger Klingenberg.

It helps to introduce new foods when such young lizards are inquisitive. Offer finely chopped greens and commercial foods crumbled into bite-sized pieces daily (inverted plastic tops from containers work well as food trays), and leave them in the enclosure throughout the day. The baby dragons will run through the food and often ignore it initially. As the days pass, however, the dragons will nibble on these foods and begin to include them as part of the daily intake.

Uneaten food, including spared crickets, should be removed at the end of each day. Water should be changed daily, and dirty water should be replaced more often as needed.

We recommend that no snacks or treats be offered to very young dragons. These lizards are growing rapidly and need to fill up on highly nutritious supplemented crickets if they are to achieve their genetic potential for size, conformation, and performance. The dragons themselves are less interested in snacks during this phase. The focus of the baby dragons should also be the focus of the owner—providing enough well-supplemented crickets in a hospitable, wholesome environment to allow for optimal development.

Common feeding problems at this stage include starvation and malnutrition. Starvation is characterized by poor growth, loss of weight, and often death. It is due to poor food intake arising from a variety of causes that can include: temperatures too cool and/or lighting too dim, which will inhibit the feeding response; feeding inappropriate foods, such as offering only salad, only commercial pellets, or crickets too large for the young dragon to eat; and large, rapidly growing dragons that may be bullying slower-growing dragons, reducing food intake in the runts.

A secondary problem from inadequate food intake is mutilation. Hungry baby dragons will nip the toes and tail-tips of other dragons. If this is observed, add an additional daily meal or increase the amount of crickets fed at each meal.

Malnutrition occurs from feeding imbalanced diets, such as unsupplemented crickets. Calcium deficiency is common, arising from deficiencies of dietary calcium and/or dietary vitamin D3 or UV-B. Young dragons with symptoms of calcium deficiency (shaking, twitching, paralysis, or lameness) need veterinary treatment and diet evaluation.

During this stage, young bearded dragons are eating machines. Growth is very rapid—bearded dragons increase their size more than 4000 percent in their first six months under optimal conditions. Crickets of an appropriate size (two to four weeks old, 1/4 to 1/2 inch) should be offered twice daily in amounts that are consumed in about ten minutes. Crickets should be supplemented every second or third meal, depending in part on the product that is used and the growth rate of the dragon.

Introduce other small invertebrates. Dragons enjoy wax worms and mealworms. Newly molted mealworms contain less chitin, and are more digestible. These, too, should be supplemented since they also lack calcium and other essential nutrients.

Offer salads of finely chopped greens and vegetables. The overall best green in our opinion is romaine because it is palatable, nutritious, and contains moderate calcium (0.7 percent), beta-carotene (over 50 retinol equivalents per gram dry matter), and fiber (35 percent). Romaine lettuce (with appropriate supplements) has been fed successfully to bearded dragons through all life stages. Other greens can be mixed in too, including dandelion, mustard, collard, kale, leaf lettuces, and bagged mixes of salad greens. These too should be supplemented to provide missing essential nutrients, especially calcium but also trace minerals, vitamins, and fiber.

Dragons enjoy colorful chopped fruits and vegetables mixed into their greens. Figs, kiwifruit sections, apples, berries, green peas, bananas, and green beans can be fed in small amounts.

High-Calcium Foods |

Poor Calcium Sources |

alfalfa and clover hays (1.5 percent) dandelion greens (1.3 percent) mustard greens (1.3 percent) spinach (1.1 percent) kale (0.8 percent) romaine (0.7 percent) |

alfalfa sprouts (0.3 percent) figs (0.2 percent) peas (0.1 percent) melons (0.1 percent) mango (0.06 percent) apple (0.05 percent) papaya (0.02 percent) banana (0.02 percent) |

As a general rule, high-calcium foods cannot be fed in great enough quantities to make up for the deficiencies of the other, calcium-deficient foods in a dragon’s diet. Supplementation with calcium is almost always needed.

Commercial diets may be offered, too. These should be crumbled or moistened if pellet size is too large. Moistened foods need to be changed daily in order to avoid mold and decomposition.

FAQ: My friend told me that spinach and kale are bad for dragons, but mine loves these foods. Can I still feed these greens?

All greens contain substances generally referred to as secondary plant compounds. Some are helpful to animals, and others can be harmful. Two substances most frequently mentioned are oxalates and goitrogens, but there are many other compounds, some riskier than these two. If you avoided every green, fruit, and vegetable that contains a potentially harmful secondary plant compound, there would be nothing left to feed! You can continue to feed spinach and kale to your dragon. Make sure they make up just a moderate part of the overall diet and that you include supplements containing calcium and trace minerals. Don’t feed diets of just spinach and kale with no additional supplementation.

During the juvenile stage, a variety of foods can be offered occasionally (no more than one or two bite-sized pieces every one or two days) as snacks and treats. These can be bits of watermelon, cucumber, papaya, cantaloupe and other melons, and mango. We know of pet bearded dragons that enjoy small amounts of turkey and cranberries on Thanksgiving and a tiny piece of fruit pie on other holidays. Care must be taken to keep the portions small. No supplementation is needed for occasional snacks.

Common nutritional problems seen at this stage include underfeeding because the offered prey are too large for the dragon. Consumption of too-large crickets may be also associated with partial paralysis. Owners sometimes want to rush into larger crickets, but be patient. Pushing baby bearded dragons to their limit on prey size is risking serious problems.

Calcium deficiency is often seen at this stage. Parasitic and infectious diseases may result from failure to keep food and water scrupulously clean. Juvenile dragons are quite active and they’ll frequently scamper through food and water, soiling everything in their path. A part of feeding management is maintenance of hygienic conditions.

In this stage of adolescence, offer crickets once or twice a day. As the dragon grows, the size of cricket can increase gradually up to adult size, which is 1 inch at six weeks. Crickets should be supplemented every second or third day, depending in part on the product that is used and the growth rate of the dragon.

Superworms are enjoyed, as are juvenile cockroaches (ones farmed as food animals; not captured pests that may be carrying pesticide residues) and young mice (both pink and fuzzy). These prey animals are enjoyed by most dragons and are conducive to but not essential for good health.

Salads become a more substantial part of diet at this stage, so more attention needs to be given to their nutritional balance. Appropriate greens include romaine and other lettuces, kale, mustard, collard, and the like. Vegetables include varieties of beans and other legumes (such as peas), corn, sweet potato, yam, and squash. Fruits include banana, melon, apple, papaya, and berries. All components of the salad need to be chopped into bitesized pieces suited to the size of your dragon. The salad should be supplemented with a light sprinkling of at least calcium. The nutritional quality of the salad improves if it is supplemented with appropriate amounts of amino acids, fatty acids, insoluble fibers, vitamins, and minerals.

Chopped hays and alfalfa pellets may be added to salads, supplying a source of insoluble fiber as well as calcium and protein. Select products that are still green and haven’t faded. Owners occasionally use alfalfa hay or pellets as enclosure substrates for their dragons. Although use of these foods reduces risks of intestinal blockage from ingestion of substrate, these products mold readily in the presence of moisture (from spilled water, fresh salads, excretory products, and misted water), which risks digestive upsets and pneumonia if the mold spores are consumed or inhaled.

Nutritional upsets may arise from overfeeding snacks and treats. Excessive intake of just one food (such as apples, berries, or meat), can lead to diarrhea. Usually, digestive upsets are self-contained and resolve within a day. Occasionally, serious gastrointestinal disease and dehydration develop, necessitating veterinary treatment. Owners may be alarmed by a change in the color of their dragon’s stool, but this often reflects simply the passage of pigments (such as orange carotenoids) from vegetables or dyes from commercial pellets.

Offer greens on paper or on a plate to reduce substrate ingestion. Active bearded dragons eventually cover their uneaten food with sand.

Adult bearded dragons should be offered four- to six-week-old crickets and/or superworms daily or every second day. Other prey for occasional feeding can include mealworms, wax worms, and other commercially farmed invertebrates, such as grasshoppers, locusts, and other field-collected insects (make sure the fields and lawns haven’t been treated) and small vertebrates such as young mice. Adult dragons also relish young lizards, so should never be allowed access to pet baby dragons in the household.

Supplemented salads should be offered daily or every second day. Commercial diets are often offered free choice (kept available so that the lizards always have access). Generally, bearded dragons are allowed to eat as much of their salads and commercial diets as they wish. This works well as long as each is nutritionally balanced and complete. Alternatively, vertebrate prey or well-supplemented invertebrate prey may be used to make up latent dietary deficiencies of the commercial products.

Snacks and treats may be offered in very small portions that can be swallowed in one gulp once or twice daily. These can include the fruits and vegetables your dragon especially likes or even food from the table (see our limitations elsewhere in this chapter).

Nutritional disorders may occur in adult dragons, especially those newly acquired by inexperienced owners. These disorders are usually due to failure to supplement or failure to provide adequate temperature and lighting, thus reducing food intake. Occasionally, oversupplementation occurs when adults are fed large numbers of crickets supplemented daily with products meant to be used only once or twice weekly. Supplements most likely to cause nutrient toxicities are those containing proportionately greater amounts of vitamin A, vitamin D3, and certain trace minerals such as zinc, copper, and iron. Calcium can also be provided in excess, leading to constipation and, if prolonged, secondary deficiencies of zinc, copper, and iodine. Excessive ingestion of calcium-containing sand used for substrate has caused intestinal impaction and death in bearded dragons.

Females may consume less food in late pregnancy because the eggs fill much of the coelomic space. During this time, the female should be offered the foods she especially enjoys eating, with attention given to digestibility and the nutritional balance of those foods. Crickets and other prey provide more calories and high-quality protein than salads or many commercial diets, so supplemented invertebrates may be especially valuable foods at this time. Despite the best of care, females often mobilize their own body stores in late pregnancy. After egg-laying, these body stores need to be replenished, and a nutritious diet should be offered daily. We prefer live invertebrates as part of this diet, along with salads.

Until data from feeding trials on aged bearded dragons are available, we offer recommendations based on the science of geriatric nutrition and our own experiences with old dragons. Senior bearded dragons tend to be less active, so they need fewer calories. However, their needs for essential nutrients remain at or near levels of younger, nonbreeding dragons. So our goals are to offer fewer calories but to maintain high-quality diets. This is accomplished most easily by offering free choice, nutritionally balanced salads daily, and feeding limited amounts of crickets and superworms. The prey are offered every second or third day, and feeding rates and amounts are adjusted according to the dragon’s body condition.

A number of commercial diets are marketed specifically for bearded dragons. These are comprised of plant- and animal-based ingredients usually in the form of extruded (and occasionally compressed) pellets. Most contain dyes to enhance colors, and many have sprayed-on odors (marketed erroneously as “flavors”) to enhance acceptance by owners as much as dragons.

These products are relatively new, and information about testing in feeding trials is limited or lacking. Because the adequacy of these diets is uncertain, we do not recommend any as the sole source of food for bearded dragons at this time.

Several characteristics are common to all pellets, regardless of the formulation or quality control in manufacture. All pellets contain minimal water—about 10–12 percent. In contrast, the water content of fresh salads is about 85–92 percent and the water content of invertebrates is about 60–70 percent. A dragon fed only pellets is receiving much less water from its food than it should. It is possible (but not yet established) that dragons can compensate by drinking proportionally more water. This means even more attention must be given to providing clean, high-quality water to dragons at all times. On the other hand, it is also possible that dragons cannot compensate for a reduced water intake, which predisposes them to kidney disease from chronic dehydration.

Most pellets utilize the ingredients and production techniques of the commercial livestock and pet food industries. The formulations meet the needs of manufacturing first and dragons second, using ingredients readily available in the feed industry. While these features aren’t inherently bad for dragons, they limit the scope and breadth of feeding such enthusiastic, interactive lizards. The ingredients in pellets are relatively few (corn, soy, poultry meal, tallow, alfalfa, wheat, and the like), whereas the palates of bearded dragons range through a myriad of foods. The deficiencies in pellet ingredient variety is compensated for by differing shapes and dyes, which may please the eye of the owner more than the palate of bearded dragons.

All pellets contain relatively little fat; about 10 or 12 percent is the limit for commercial pellets sold in paper and cardboard containers. Salads contain even less fat. In contrast, invertebrates contain 30–60 percent fat. This fat is essential for bearded dragon nutrition, providing needed calories for growth, reproduction, and good health, along with essential fatty acids for development of vital tissues, especially brain. We know of breeders observing poor growth in juvenile dragons who had been fed low-fat and relatively low-protein pellets. The dragons improved markedly once the diet was changed to a pellet with more fat.

Another type of commercial dry food has been fed successfully to bearded dragons—dry dog and cat foods. Many of these foods contain enough fiber and levels of fat and high-quality protein, which support growth and reproduction. However, we do not recommend feeding cat food to bearded dragons. Modern commercial cat foods are formulated to produce the excretion of acid (to maintain cat urinary health), which increases calcium excretion, predisposing a bearded dragon to calcium deficiency. Dog foods are not formulated in this way, and should help to maintain calcium balance and good bone in dragons. If owners insist on feeding a pellet, we suggest that dry dog food should serve as only one-half of a dragon’s feeding regimen, although we prefer a diet of supplemented invertebrates and fresh salads.

In mammalian species, feeding only pellets has led to digestive disorders (in herbivores and omnivores) from a lack of long-stem fibers, poor growth (in omnivores and carnivores) from a lack of fat, and behavioral disorders (in all species) from the monotony of the diet. So owners wishing to feed only pellets to bearded dragons should be cautious and observant.

If you wish to feed your dragon a strictly commercial diet with no crickets or salads, do not try this before the dragon is two to four months of age and even later is better. The changeover must be gradual, with free-choice offering of the commercial product (offered fresh daily), and gradual removal of other foods over several weeks.

Owners can assess the adequacy of their dragon’s diet by careful observation. A well-fed bearded dragon appears plump and relatively well muscled. There is a slight paunch to the dragon’s belly. Pelvic bones should be barely visible in older juveniles and young adults, but the very young, very old, and actively breeding females may exhibit pelvic bones with only a modest covering of subcutaneous fat. Tails should be wide at the base and well fleshed.

A well-fed dragon is alert and aware of activity in its surroundings. It should actively move about the enclosure, choosing at various times to bask, eat, dig into substrate, and soak in its water dish. The dragon should eagerly eat live food and enjoy salads too. Stools should be formed rather than sloppy. Like other meat-eaters, dragon feces may have a pungent odor, even when the individual is healthy.

An exception to the above description is when the bearded dragon is shutting down for winter but is otherwise healthy. Food intake and activity is greatly reduced in lizards at this time. Weight loss, however, should be minimal.

Never feed lightning bugs (fireflies) to your bearded dragon. These are highly toxic, resulting in rapid death of a bearded dragon after the consumption of even one firefly. Also, avoid feeding spiders known to be venomous to man, such as black widow and brown recluse spiders.

The toxicity of avocado to bearded dragons is unknown, but it is toxic to cage birds. Do not feed any part of an avocado plant to a bearded dragon until its toxicity in reptiles has been determined. Avoid feeding wild unidentified mushrooms and wild, brightly colored, unidentified berries. It’s best to avoid feeding plants known to be toxic to mammals, such as bracken fern, equisetum, buttercup, poppy, rhododendron and the like. Most houseplants should be avoided, but pothos is safe (if untreated) and greatly enjoyed by bearded dragons.

Also avoid foods containing theobromine (in tea and chocolate), alcohol (in certain candies, drinks, vanilla and other flavorings), and caffeine (in tea, coffee, soft drinks). Some foods are not toxic but may lead to digestive or metabolic upset in bearded dragons because of high sugar content or the presence of artificial sweeteners. Avoid feeding candies, soft drinks, and sports drinks to your dragon.

While processed foods for people, such as pizza, nachos, and cheeseburgers, are not generally recommended for bearded dragons, the occasional small nibble will likely do little or no physical harm and may provide a little cement to the human-pet bond.

Mystery Deaths

FAQ: I thought I was doing what was best for my dragons, but now two are dead! They’ve been outside for the summer in a screen cage set up with ample shade and areas to bask in the sun. I feed and water them before work each morning and hose out the cage each evening. Last night, about an hour after cage cleaning, I found two of them dead! I know they were feeling okay because they still had bugs in their mouths. What happened?

While we can’t make diagnoses long distance, we’re suspicious that your dragons died from eating fireflies. These insects, also known as lightning bugs, are especially prevalent in the eastern U.S., are active in the evening, and seem to be attracted to damp grass and foliage. We know one breeder who lost dozens of adult dragons one summer during a drought, when he began hosing the cages in the evening. Fireflies would then enter the cages and be gobbled up by the dragons. It only takes one firefly to kill a dragon, and death occurs very soon after swallowing the bug. We suggest that you change your routine, hosing the cages in the morning, prior to feeding, and offering another meal in late afternoon (with no additional hosing) to offset late-day dragon hunger.

Plants play a major role in the nutrition of bearded dragons. Plants, however, contain much more than just nutrients. A broad category of substances, termed secondary plant compounds, impacts the feeding of dragons.

Oxalates bind calcium and trace minerals in the digestive tract, preventing their absorption and risking deficiency. Oxalates are found in varying amounts in spinach, rhubarb, cabbage, peas, potatoes, beet greens, and many other plants. These foods do not have to be avoided entirely, for nutritional deficiencies are risked only when these foods are fed frequently or as the sole source of nutrition without supplementation. Provision of the usual supplements of calcium and trace minerals and offering a varied diet eliminates most risk.

Goitrogens bind the trace mineral iodine, risking goiter or hypothyroidism. Goitrogens are found in highest quantities in cabbage, kale, mustard, turnip, rutabaga, and other cruciferous plants. These foods can be fed as part of a varied diet along with provision of a supplement that contains iodine (which can be as simple as iodized table salt or, better, iodized “lite” salt containing iodine, sodium, potassium, and chloride). Many commercial supplements contain adequate levels of iodine. The mineral iodine is itself toxic in large quantities (also acting as a goitrogen), so care should be taken not to overdose with commercial supplements, iodized salt, or kelp.

There are many other secondary plant compounds, and it is unfortunate that oxalates and goitrogens receive more attention than needed, while other substances are ignored. For example, many plants contain substances with hormonelike activity (such as phytoestrogens in soybeans) which may impact bearded dragon reproduction. A large number of different plant fibers may affect bearded dragon digestion and intestinal health. Other compounds in plants influence cognitive function, acting as stimulants or sedatives. A general rule for feeding plants to bearded dragons is to offer a variety of produce from local markets of the kind and quality that you yourself would eat. Supplement this produce with calcium and other essential nutrients. And include prey as part of a varied, balanced diet.

The suggestions we’ve made here are general guidelines, and many factors will affect the diet and feeding management of dragons in specific situations. For example, those housed outside year-round with exposure to natural sunlight certainly don’t need UV-B-generating bulbs and may not need a dietary source of vitamin D3. They may consume trace minerals from the soil, and an array of secondary plant compounds if offered wild plants. These dragons will have nutritional needs that differ from a pet dragon housed indoors full-time.

Feeding regimens may have to be adjusted, depending on your dragon’s condition, its environment, and your management. A change of enclosure or adding cage mates, for example, can alter feeding responses, as can the dragon’s attainment of sexual maturity.

Females that are bred every year will have greater nutritional demands than a solitary pet that never reproduces. Breeding females are subjected to an obvious stress, and stress itself increases nutrient demands, even in the absence of reproduction. Stress may be insidious and not immediately obvious to dragon owners. For example, stress can arise from chronic excessive exposure to vibrations or light, too much handling or rough handling, or unwanted attention by the family dog or cat.

Illness affects nutrition, too. Bearded dragons that are sick or in pain often don’t want to eat, which can impair recovery from illness and surgery. Disease itself impacts nutritional needs, and dragons may lose weight when sick, even though food intake has been maintained.

Bearded dragons can be underfed or overfed. Generally, young animals are most at risk for underfeeding because they are growing so rapidly. Many cases of underfeeding are due to errors in husbandry. Adult dragons are most at risk for overfeeding because their growth and activity have slowed. Carefully observe your dragon’s body condition accordingly, adjusting the amounts of foods offered to avoid of under- and overfeeding.

Bearded dragons are susceptible to nutrient deficiencies and excesses. The most common is metabolic bone disease, caused by a deficiency of calcium and/or vitamin D3. It can be prevented by supplementing crickets and salads with calcium (calcium carbonate is inexpensive and widely available) and vitamin D3, and by exposing dragons to natural sunlight and UV-B-generating bulbs.

Oversupplementation of certain vitamins and minerals can pose risks of toxicity. This is more likely in adults, so care should be taken to reduce supplementation schedules as your dragon grows older. Excessive supplementation with calcium, without provision of adequate levels of trace minerals, risks secondary deficiencies of zinc, copper, and iodine.

Excessive feeding of snacks and treats risks dietary imbalance and nutritional deficiencies as well as digestive upsets. Limit snacks to small portions, and offer no more than once or twice daily. The goal is to limit snacks and treats to about 10 percent of the total daily food intake.

There is not one right way to feed all bearded dragons. However, careful application of the guidelines in this books and observation of your dragon, with consideration of your husbandry style, will result in a well-fed dragon.