Many people have set out to become rich breeding bearded dragons, hoping to meet the high demand for one of America’s most popular pet lizards. Today most of them are out of business. They lasted only a couple of years because their projects lost money or were barely profitable. Indoor space and setup, electricity, food, and maintenance costs can be surprisingly high when keeping large numbers of bearded dragons indoors. In warmer areas, outdoor setups such as greenhouses are more economical but can bring other problems such as fire ants and inclement or unpredictable weather. As anyone who has made a living breeding amphibians and reptiles will tell you, it has to be a labor of love because it takes a great deal of work to make it in what many consider to be a cutthroat business. To be successful as a commercial breeder means doing research on the market, finding ready outlets for your animals, maintaining careful records of your breeding stock’s performance and carefully planning the expenses and expected returns.

This green-house breeding setup has individual pens on one side and baby-rearing enclosures on the other. Greenhouses reduce electrical costs in commercial bearded dragon breeding operations.

In this outdoor commercial breeding operation, the dragon pens have smooth fiberglass walls that pre-vent escape and can be covered with shade or plastic as needed.

Herpetoculture is a very competitive and fast-changing business. What is popular today may not be marketable a few years from now, and what is rare today can become tomorrow’s standard pet-trade fare, bred by every pet owner who cares to keep a pair together. To survive on a commercial level means constantly evaluating the market, the state and efficiency of your business, and your breeding stock. Ideally, you should always be looking to produce more vigorous, as well as more beautiful, dragons as economically as possible.

A key to the success of any commercial breeder is record keeping. This means, at the very least, giving each animal a number, recording the parents of a particular clutch, the number of eggs laid by a female, and the number of eggs successfully hatched. Keeping digital photographic records of individuals, labeled with their record number, can also allow you to keep digital files in a computer that can be readily accessed when planning breeding projects. It saves time and allows a broader overview than examining individual animals in a collection.

Many breeders have lines of red/gold dragons crossed with Sandfire bearded dragons. The results combine characteristics of both morphs.

Egg clutches should be labeled with their parentage and the date laid. Records should also be maintained on incubation temperature and duration. Often dragons are good producers for about three years before the numbers produced start declining significantly. Thus, replacing commercial breeding stock is an important way to optimize production. This also means planning ahead to raise replacement stock. If your goal is to develop your own unique lines or to maintain existing lines, careful record keeping will prove invaluable in identifying the best individuals for the process. Expenses and sales should also be carefully recorded for tax purposes and for allowing you to hone the efficiency of your business.

Selective breeding is a term that refers to crossing animals with desirable traits to establish particular characteristics (such as color) in a line while maintaining vigor (size, health, and reproductive ability). Most of the attractive bearded dragon morphs available today were developed in this manner. Although inbreeding (breeding animals that are closely related, such as brother x sister or father x daughter) is a common and necessary component of selective breeding, it can decrease line vigor if practiced extensively over several generations. For this reason, selective breeding must also include outcrossing in order to reintroduce vigor from an unrelated gene pool while retaining the desirable trait.

Three baby bearded dragons, probably siblings, hang out together. Inbreeding with siblings is part of selective breeding.

The opposite of inbreeding, outcrossing consists of breeding animals that have desirable traits with unrelated animals. It is done to maintain line vigor or to add additional characteristics to a line. For example, German giants have been crossed with other lines of bearded dragons to increase size, reproductive vigor, and fecundity. Although first generation offspring from an outbreeding may bear little resemblance to the bright-colored parent, crossing these outbred first generation animals together will usually result in a percentage that manifest the desirable traits. Selective breeding can then be used to “fix” or intensify these traits.

The first requirement for breeding bearded dragons is to have at least one healthy young adult male and one healthy young adult female. The second is to keep them together. The third requirement, usually after the first breeding season, is to allow them a winter shutdown or rest period. When they’re mature they will tend to brumate no matter what you do. In captivity, breeding starts after winter shutdown is over, beginning in the spring and often continuing into fall.

Many keepers claim they have their best breeding success when they keep bearded dragons in individual pairs, and this may be true when they’re kept in small indoor enclosures. In our experience, it is possible to keep trios, one male and two females, with good breeding results. For commercial breeders, the expense of maintaining any more males than necessary can become cost prohibitive. In larger enclosures, 72 x 30 inches minimum, we keep ratios of two males and four females and have found this to be the most effective ratio for commercial-scale breeding.

With bearded dragons raised under intensive rearing conditions, breeding begins by as early as five to six months of age and can extend through the first winter. By twelve months of age, bearded dragons raised under intensive conditions may produce up to three clutches of eggs. During the course of their second year (twelve to twenty-four months) they can lay up to seven clutches of eggs (two to three clutches before the first winter shutdown and four to five clutches after winter shutdown).

Under less-intensive rearing conditions in outdoor greenhouses and given a first year winter shutdown, sexual maturity may not be reached until bearded dragons are twelve to fifteen months old. Three clutches will be produced in the first eighteen months of age and after the second (greenhouse conditions) winter shutdown up to seven clutches for typical bearded dragons. The third year, only three to four clutches will be produced.

In this green-house operation, dragons are housed in large plastic bins. Panels of polyurethane foam are used for shade.

This is a pattern we have seen in several other species of quickly maturing lizards with high reproductive rates. The females are prolific breeders for the first two to three years and then steadily decline in production. By six years, egg production is insignificant, and by seven years, it has often ceased completely. One important lesson is that from the point of view of a commercial breeder, buying large adult captive-raised females is usually not the best investment. One-year-old animals are probably the best buy for breeders.

In captivity, beginning with their second winter, most bearded dragons undergo a period of winter shutdown. During this time, they become inactive, spending extended periods of time in shelters and eating little or no food. This period of brumation appears necessary for long-term success in breeding bearded dragons.

As a rule, most mature bearded dragons shut down on their own, no matter what conditions they’re kept in, but a shift in environmental conditions also plays a role in initiating brumation. In outdoor or greenhouse conditions, the reduction of the daily duration of light exposure and dropping temperatures naturally induce brumation. In the home, starting in the first two weeks of December (in the Northern Hemisphere), light exposure should be reduced to ten hours a day (adjust the timer) and spotlights replaced with lower-wattage bulbs so that the temperature at basking sites is 75–80°F. In addition, all secondary heat sources such as hot rocks should be turned off, and night temperatures should drop into the 60s. In most homes, one way to achieve cooler night temperatures is to keep bearded dragons in tanks at floor level. This winter shutdown regime is maintained for about two months, starting sometime in December and ending in February. After this period, vivarium conditions should be returned to a normal regime.

Visual Perspectives and Breeding

FAQ: I have a pair of inland bearded dragons that I purchased two years ago and I have yet to see signs of breeding. They are in a 36-inch-long enclosure with a small one-tube fluorescent fixture and an incandescent bulb. What am I doing wrong?

We were surprised to hear of people failing to breed their bearded dragons, considering these lizards are among the easiest reptiles to breed. Surprisingly we have received several of these reports and we attribute these failures to improper husbandry. Remember that bearded dragons are diurnal and depend on visual clues to elicit breeding behaviors. A common cause of breeding failure is too small of an enclosure. Bearded dragons benefit from the greater range of visual perspectives and social behaviors possible in larger enclosures. Another cause may be inadequate lighting. Animals kept in setups with low levels of lights may also fail to breed. A simple method for getting bearded dragons to breed was discovered by a well-known bearded dragon expert. Remove the dragons from their cage and place them on the floor of a room in an area lit by a spotlight. Within minutes the male will usually head bob and attempt to breed the female. If she is receptive, you will usually end up with a clutch of fertile eggs.

About three to four weeks after the end of winter shutdown, bearded dragons begin reproductive activities, including courtship, territorial and competitive behaviors, and copulation. In bearded dragons, copulation is typical of what is observed for most lizards. A male bites the fleshy portion of a female’s nape, places part of his upper body on her, then scratches her with his hind leg to encourage her to position herself for copulation. The male then twists his lower body and inserts a hemipenis. The sexual act lasts several minutes.

Gestation, the period between copulation and egg-laying, can be difficult to accurately determine in reptiles because females of many species can store sperm for extended periods of time. As a rule for bearded dragons, the interval between a first breeding and egg-laying will be about four to six weeks. Subsequently the interval between clutches during a breeding season can vary depending on a number of factors and be as short as three weeks or considerably longer.

As the gestation period nears its end, the eggs pass through an area of the oviduct surrounded by the shell gland, which forms the calcareous shell. After they pass through the shell gland, you can often see the outlines of individual eggs (now more rigidly enclosed) pressing against the abdominal wall. They look like grapes or marbles. Shortly after, the lizard displays behaviors such as investigating possible laying sites and digging several test burrows.

At this time, it is important to provide the pregnant (or gravid) female with a nest site of at least 12 inches of burrowing substrate. Most breeders provide damp soil as substrate. If the substrate is too shallow or causes repeated collapse of a burrow, the female may refuse to dig a nest and instead lay an egg a day on the surface until she finds a suitable laying site. (This presents a problem because uncovered eggs have a high rate of dehydration and may be harmed by exposure to excess heat or sunlight.) Or, she may dig several test holes and lay scattered eggs on the surface. She may eventually lay the rest of her eggs in shallow soil, but instead of digging her preferred nest (one deep enough that she can completely fit into, with the tip of her snout at the nest hole) she may lay them with the front of her body exposed.

Only the tip of the female’s snout can be seen at the entrance to the burrow when she lays her eggs.

An accessible 5-gallon plastic flower pot filled with moistened potting soil generally works well as a nesting site. After introducing the damp soil, compress it by pressing down on the soil surface with your hand. This makes the soil less likely to collapse as the female digs her nest. Alternatively, nesting sites can be made by placing soil at least 12 inches deep at one end of the primary enclosure. Also, the female can be placed in a 30- or 55-gallon trashcan with a least 12 inches of soil in the bottom. Gently press down the moistened soil before introducing the female into the container. Substrate moisture is believed to provide important egg-laying cues regarding the suitability of the laying medium. Our records show that most female bearded dragons lay their eggs between 1 P.M. and 6 P.M.

In our inland bearded dragon collections, clutch sizes have ranged from as few as seven to as many as forty-six eggs, with most clutches ranging between twenty and thirty eggs. The German giant line of bearded dragons has been reported to lay in excess of fifty eggs per clutch, with a record of sixty-eight eggs. Clutch size varies depending on size, age, morph, and line of the parents. As a rule, younger, smaller females lay smaller clutches and old females eventually lay smaller and fewer clutches. Numbers of clutches can also vary from as few as one in first-year breeders to as many as seven in second- to third-year breeders.

Carefully move eggs from the nest to an incubator.

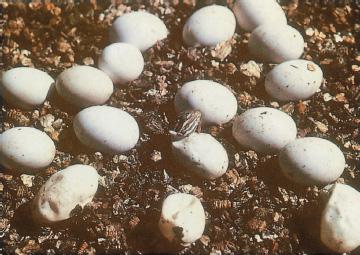

After your dragon lays her eggs, carefully dig through the soil using your fingers or a tablespoon to expose the egg clutch. Then transfer the eggs to an incubation container such as a plastic storage box or an incubator containing 1 1/2 inches of incubating medium. The media most commonly used by breeders are coarse vermiculite, perlite, and a 50:50 mix of perlite and vermiculite. We currently use only perlite as an incubating medium for bearded dragon eggs. We add water to the medium until it feels moist but not soggy, until it barely clumps when held in the hand but does not drip water if squeezed. (This is about 4 parts incubating medium to 3 parts water by weight, not volume.) We expose part of the eggs to allow for monitoring. We half bury eggs horizontally in the medium, leaving a small space between each egg. If you are using plastic containers as incubators, you should use a cover and place three pinholes (use a heated nail held in pliers, or a fine drill) in the top, leaving at least 1 1/2 inches of air space between the top and the eggs.

This female inland bearded dragon is next to her excavated nest.

The ideal incubation temperature for bearded dragons is 82–85°F. To provide this, most small-scale breeders use inexpensive poultry incubators such as the Hovabator. Large-scale breeders construct heated cabinets using either lightbulbs or heat tape controlled by a thermostat. Careful calibration is critical to prevent overheating. Temperatures that are too warm (above 89°F) will result in the death of the embryo as will temperatures that are too cool (long-term at less than 75°F or short-term at cold temps, such as low 60s and below). Another important step is to check for hot and cool spots in the incubator. A thermometer and thermostatic control are essential to good monitoring.

It is also important to monitor moisture content in the incubation substrate. Most breeders do this by picking up a clump of substrate, rolling it between the fingers and pressing it into a ball. If the substrate still feels damp, it is probably fine. If it feels almost dry, then the substrate surface should be misted lightly. Substrate can be checked weekly, but if it is found to be too dry, check daily for a while and mist as necessary.

Humidity within the incubator can be monitored as well. For a simple incubator (such as a Hovabator) with substrate placed directly on its floor, adding a small container of water helps to maintain appropriate humidity levels. If using a thermostatically controlled incubator, there should be little condensation on its sides. However, if you are incubating eggs in a room with fluctuating day/night temperatures, there can be considerable condensation. Usually this is not a problem if the substrate is appropriately moist. Adding ventilation holes to the sides of the egg container can reduce condensation but will hasten the rate of substrate drying as well.

Incubation time varies depending on species. Pogona vitticeps eggs range from fifty-five to seventy-five days depending on temperature. Lawson’s dragon (P. henrylawsoni) eggs will hatch in forty-five to fifty-five days, and eastern bearded dragon (P. barbata) eggs hatch in sixty-nine to seventy-nine days. With most clutches, all eggs will hatch within twenty-four hours of the first hatching, but in some, the clutch may take as long as six days.

The process of properly calibrating an incubator temperature can require several hours with homemade incubators or inexpensive poultry incubators. We recommend that an incubator be properly calibrated at least twelve hours before the eggs are introduced. To calibrate an incubator, adjust the thermostat so that the temperature inside the incubator matches the desired setting. To get a temperature reading inside the incubator, place a mercury thermometer inside so it is visible through a window, or install a digital thermometer with an external probe. Placing the probe inside the incubator and setting the switch to out/probe will give you a continuous readout as you adjust the thermostat. Because it takes time for the air temperature to equilibrate inside the incubator, several thermostatic adjustments will be required over a few hours for accurate calibration.

Note: It is important to keep the incubator in a room cooler than the desired incubation temperature, particularly during summer heat waves. Remember that inexpensive incubators heat but do not cool, so they cannot lower the incubator temperature below ambient air temperature. Also, take into consideration that brief exposure to high temperatures (above 90°F) is more likely to kill a developing embryo than brief exposure to cool temperatures.

Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination in Bearded Dragons

FAQ: Based on the sex ratios of bearded dragons hatched in my collection, it appears that incubation temperature could play a role in determining the sex of bearded dragons. Do you think it’s possible?

Temperature-dependent sex determination (TDSD) is a complex subject best resolved by genetic research and experimentation. The only possible answer we can give at this time is that there are indications that there may be TDSD in bearded dragons. In the last couple of years, clutches that we have incubated at 82–84°F have yielded a higher proportion of males than in previous years when eggs were incubated at 84–86°F. One breeder told us that a clutch he incubated at 82°F yielded mostly males. Other breeders of frilled dragons have reported that they have had a high male ratio when eggs were incubated at a steady 84–85°F. Temperature-dependent sex determination in bearded dragons has yet to be fully understood but will likely be clarified by additional data from breeders who keep careful records of incubation temperatures and monitor hatchlings until their sex can definitely be determined.

Many herpetoculturists correctly warn against turning reptile eggs in the later stages of development. Lizard eggs begin to develop from the moment of fertilization so development is usually well on its way by the time the clutch is laid. At a certain stage in its development, the embryo forms an allantois, a membranous outgrowth from the midgut. This eventually expands and fuses with one of the membranes that encloses the embryo, called the chorion, to form the chorio-allantoic membrane, an area that allows gas exchange through the overlying shell. Typically, the chorio-allantoic membrane forms at the top section of a resting egg with the back of the embryo curved beneath the allantois. Thus, in incubating eggs, the approximate position of the developing embryo is toward the top, close to where gas exchange readily occurs. Turning the egg in the later stages of development will shift the gas exchange area and can cause compression, which, depending on the egg position, may suffocate the embryo. So, the general rule is to avoid turning eggs once they have been placed in an incubator.

A rare example of Siamese twin bearded dragons, which like most abnormal bearded dragons did not survive. Photo by Jerry Cole

To keep a record of the original placement of eggs, draw an X on top of each egg with a soft-lead pencil. In case of accidents or late discovery of eggs, the eggs can also be “candled” to determine the embryo position. To do this, place a bright light behind a pinhole in a sheet of cardboard, and view each egg with the light shining through it. The developing embryo will appear as a dark mass. Place the egg in the incubator so that the dark mass appears at the top.

Several factors can prevent eggs from hatching. When eggs show signs that they are going bad, the timing can indicate probable causes. First check incubation parameters such as substrate moisture and temperature. If eggs incubated under proper conditions show early signs of collapse or molding, infertility (eggs aren’t fertilized) is often the cause. This can be verified by slitting the collapsed eggs and checking for signs of early embryonic development and blood vessels. Other factors that can cause the early demise of embryos include genetics and disease.

Late stage death can be caused by genetic factors, improper temperatures or moisture levels, and possibly by faulty yolk composition. Work we have done with other species suggests that if incubation temperature is too high there can come a point when increased metabolism and higher oxygen requirements of late-stage embryos may exceed the amount of oxygen diffusing through the shell. At the first signs of late-stage egg death (collapse and no hatching by thirty-six hours) we check temperature and lower it a few degrees.

Another cause of egg hatching failure may be linked to temperatures that are too low and extend incubation for too long. Much to our surprise, some lizard eggs incubated at relatively cool temperatures showed near-term hatchlings with soft bones and rubbery snouts and legs—signs of metabolic bone disease. Our current hypothesis is that incubation periods that extend too long can sometimes result in large hatchlings with depleted calcium reserves. Finally, it has been hypothesized that yolk compositions can be directly affected by diet and supplements fed to the female, resulting in inadequate or excessive amounts of certain nutrients. These deficiencies or excesses may harm developing embryos, and this is a topic that deserves further study.

In many areas, carrion flies may infest bearded dragon eggs. These annoying pests take advantage of any deterioration or rupture of the shell to feed on the egg contents and lay their eggs. They are readily attracted to the smell of eggs that have gone bad, which is one reason you should remove these eggs as soon as they are noticed. Otherwise, carrion flies will lay their eggs in rotting dragon eggs, and before long your incubator will be infested with hundreds of these flies. If many carrion flies are in your incubator or the surrounding area, they will wait like predators for any opportunity to feed on animal matter, including a baby bearded dragon that has just slit its shell. In most cases, baby dragons will hatch before any real damage is done, but check for maggots in the umbilical area and in any remaining egg yolk. The maggots can be rinsed off with tap water.

This clutch of bearded dragons is hatching.

For twenty-four hours prior to hatching, bearded dragon eggs sweat to varying degrees; the sweating is followed by a slight collapse and noticeable loss of turgidity of the egg twelve hours prior to hatching. Healthy, vigorous animals usually slit through the egg shell (using an egg tooth at the tip of the snout) within a few hours of this initial collapse. After hatching, newborn dragons may still be coated with albumin and will remain within the egg for several hours. They should not be disturbed or removed from the incubation container until they have emerged from the eggs and show signs of activity. After the hatchlings are observed to be active, they can then be transferred to rearing containers.

FAQ: I recently had a clutch of bearded dragon eggs. After the initial collapse that precedes hatching, a number of babies hatched but several failed to slit the eggs. Could I have manually removed the babies?

In our experience, manually removing babies from eggs results mostly in failure. At best, you can slit the eggs after twenty-four hours of the initial collapse, and hope.

To slit an unhatched egg, use cuticle scissors to penetrate the shell and cut close to the shell, making sure that you do not penetrate past the shell surface. The slit should run through the center third of the egg. Once the egg is slit, leave it alone. In time, a baby lizard may emerge on its own. Never manually pull a lizard out of the egg following incision. In our experience lizards that are manually removed usually die. In spite of these procedures, we have found that most lizards that fail to slit their eggs on their own also fail to emerge from manually slit eggs. Of the few that do, most go on to die. In other words, the value of slitting unhatched eggs is questionable.