Part of the fun of owning reptiles is to experience the variants produced by breeding. Whether the animal has a special size or color, the variants are usually referred to as morphs. Perhaps nowhere are morphs more exciting and challenging than those in the bearded dragon world.

Inland bearded dragons have a wide distribution in Australia and consist of many populations adapted to specific habitats ranging from sandy deserts to savannas, mountains, and woodlands. The variation found in these wild populations has allowed herpetoculturists to produce the range of morphs currently established in captivity. According to Hauschild and Bosch (2000), the popular inland bearded dragons with high amounts of red originate from the central part of their range—an area characterized by red sands—while the more yellow specimens are found in the southern yellow sand deserts. The availability of these more colorful desert morphs in the early 1990s allowed the selective breeding of many colorful varieties of bearded dragons available today.

These original brown and tan bearded dragons with small amounts of red and yellow, mostly on the head, were first imported into the U.S. in the late 1980s. “Normals” were the most readily available bearded dragons until the herpetocultural revolution generated imports of red/gold dragons in the 1990s. Because of the increased demand for more colorful dragons, most normal dragons in captivity have, over time, been crossed with red/golds to the degree that it is becoming increasingly difficult to find representatives of the once common normal strain. This is the same herpetocultural pattern we are now seeing with leopard geckos—selection for brighter colors and bolder patterns causing a decline in the pet trade of the original, normal-colored individuals.

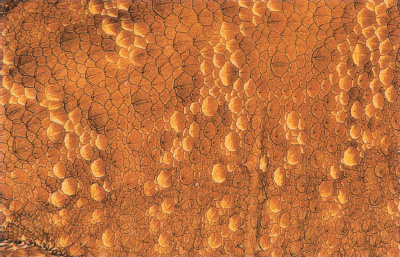

Note the complex scalation in this close-up of a bearded dragon’s back.

Pete Weis introduced this morph into the U.S. hobby. German giants are big dragons with a lot of spunk and are generally prolific breeders. They are colored mostly in browns and tans. The head is less massive than in typical dragons. The iris is a silvery gold that contrasts sharply with the pupil. Because of their high fecundity, German giants have been crossed with other lines to increase reproductive vigor. The giants, however, can be a little more prone to aggressive behavior than are typical dragons. Large males sometimes exceed 24 inches in length, and females can lay single clutches of more than fifty eggs, with a record of sixty-eight eggs (Kevin Dunne, pers. comm.).

German giant morph of the inland bearded dragon. Photo by Kevin Dunne.

A great revolution in dragon breeding followed the importation of individuals with extensive amounts of reds, oranges, and varying amounts of yellow in the early 1990s. Originating in Germany, red/gold dragons allowed the selective breeding of the many orange, red, and yellow lines available today, including the Sandfire line. The original German breeding stock was said to have come from the red deserts of the interior of Australia. Additional imports of red/gold crosses between lines (e.g., normal x red/gold; and Sandfire x red/gold) and selective breeding have allowed various breeders to develop their own unique lines. Because yellow and red pigments are synthesized by skin cells called xanthophores, the term xanthic may be the most appropriate to describe lines characterized by varying degrees of red or yellow coloration. Red/golds could be considered the most basic examples of xanthism in bearded dragons.

Extreme forms of xanthism, developed through selective breeding for extensive saturation of red/orange or yellow, qualify as hyperxanthic. The first established hyperxanthic lines of bearded dragons were the Sandfire lines developed by author Robert Mailloux and characterized by bright orange to orange-red coloration distributed throughout the upper body and limbs to the point of masking most of the typical pattern seen on dragons.

The Sandfire line was started from a single unusually bright colored female of the red/gold morph with orangered extending to the limbs. Selective breeding for increased saturation of the bright orange coloration established the Sandfire characteristics and this morph is now produced with regularity. The full expression of the hyperxanthic trait is dependent on the right light exposure. Sandfire bearded dragons raised under standard indoor conditions are more brightly colored than typical dragons, but they do not come close to the intense orange-reds of Sandfire animals raised outdoors or in sun-exposed greenhouses. One hypothesis is that the saturation with red/orange pigment is a dermal response to sunlight exposure, much like tanning in human skin.

In addition to the Sandfire lines, there are several other hyperxanthic lines, some of which may also include varying degrees of hypomelanism (reduced dark pigmentation) such as some of the yellow bearded dragons bred in the U.S. and in Europe. Yellow lines in general have proven difficult to establish, many showing poor reproductive vigor, poor hatch rate, or poor hatchling survival. Careful breeding and outbreeding may succeed in establishing a hardy yellow line in the not too distant future.

This was a line first introduced by Ron Tremper and characterized by a barred pattern running the width of the body.

Although some juvenile bearded dragons have a striped pattern, this usually fades by the time they mature. Nonetheless, some individuals retain pale stripes into adulthood, a trait that could be selected for.

A high contrast red/gold x Sandfire cross

Young red/gold bearded dragons show early signs of red coloration.

Red/gold males can develop brightly colored heads that contrast sharply with their less colorful bodies.

Red/gold crosses can be highly variable in appearance and are an important source of new morphs.

Top of the line Sandfire bearded dragons are solid orange and nearly patternless. This vivid coloration has only been achieved after three or more months of daily exposure to sunlight.

The Sandfire trait becomes apparent in subadults and intensifies as these bearded dragons grow to sexual maturity.

An older female Sandfire bearded dragon

Close-up of the skin of a Sandfire bearded dragon

Sandfire yellow bearded dragon

An outstanding example of a yellow bearded dragon produced by Dragon’s Den Herpetoculture. Photo by Kevin Dunne

A yellow bearded dragon produced by Sandfire Dragon Ranch

A yellow line of the bearded dragon originally developed in England by Luke Yeomans. Photo by Jerry Cole

Juvenile tiger morph

Adult tiger morph bearded dragon

Various degrees of striping are seen in baby bearded dragons, and some dragons retain the stripes into adulthood.

Striped hyperxanthic bearded dragon

The Snow dragon is a hypomelanistic line produced by Dragon’s Den Herpetoculture. Photo by Kevin Dunne

A fourteen-month-old hypomelanistic bearded dragon. Photo by Kevin Dunne

Gold iris morph bred by Robert Mailloux. Photo by Corey Blanc

Gold iris bearded dragon produced by Kevin Dunne. Photo by Kevin Dunne

Bearded dragon breeders are actively working on selecting and developing new morphs. This is an unusual form of Sandfire bearded dragon with lightly colored reticulations.

A Sandfire novelty with pink and purple highlights.

Notice the striking combination of pattern and color in this Sandfire novelty with pink and purple highlights

Pastel morph of the inland bearded dragon. This is a male hypomelanistic red/gold. Photo by David Travis

These are dragons in which the dark pigmentation (melanin) is greatly reduced or nearly absent. Although they’re very bleached in appearance, they are not true albinos because their eyes remain pigmented (in true albinism eyes are pink or orange/red). One of the characteristics of hypomelanistic dragons is a clear-colored nail base. At least two lines have been developed. One is the Sandfire “Pastel” line developed by Robert Mailloux, which is characterized by high-contrast oranges against a pale background. Pastels can also have light bluish to purplish body patterns, probably caused by clear skin areas that expose underlying iridophores, which are skin pigment cells that underlie xanthophores and have the ability to reflect light of specific wavelength. Another popular hypomelanistic line is the Snow dragon line established by Kevin Dunne, owner of Dragon’s Den. As the name indicates, top of the line Snow dragons are mostly bright white. The high contrast between the gold iris and the near white body of Snow dragons makes this a particularly appealing morph. Depending on their backgrounds, hypomelanistic dragons can range from nearly pure white lizards to whitish animals with grayish patterns. Others may have intense yellows, oranges, or reds against a pale background.

These are uniformly colored, gray-white dragons with dark irises and bluish eyelids. A small number of breeders are working to establish this unusual morph.

There is at least one natural population of gray-green bearded dragons in Australia. In captivity a pale green line was developed through selective breeding in England, but it has been difficult to maintain.

We have had a few specimens hatch with unusually light, bright silvery-gold irises that contrast sharply with a black pupil. Kevin Dunne of Dragon’s Den has also reported hatching individuals with light-colored irises. This is an attractive trait that will likely be developed through selective breeding.

Bearded dragons are becoming one of the most popular pet reptiles of all time, so it should be no surprise that there is an active interest in developing new, attractive, and marketable lines of this species. As with certain kinds of fish, such as koi carp and goldfish, or with lizards such as the popular leopard gecko, we can expect the availability of many more attractive and unusual morphs of bearded dragons in the future.

An unusual green morph of P. vitticeps photographed in the wild by Robert Mailloux