text and photos by Roger Klingenberg, D.V.M.

When bearded dragons were introduced as a new type of reptile pet several years ago, it appeared that we had found a truly bullet-proof lizard. Bearded dragons were hardy, good eaters, and easy to care for. Health problems were rare, and most disorders were chalked up to glitches in evolving husbandry techniques. As always happens with new reptiles, our knowledge base of the bearded dragon expanded exponentially as the species became more popular.

We have recently found that bearded dragons are not bulletproof, and while quite hardy, these lizards are afflicted by various ailments. Our medical and surgical knowledge of bearded dragons is increasing, but customer demand is what drives the evolution of new medical information and techniques. Much of what is medically applied to the bearded dragon is information we have borrowed from our work on the green iguana. We need more species-specific information, which is where you, the bearded dragon owner, can help. Participation and contribution to research at your local herpetological society or with the Association of Reptile and Amphibian Veterinarians is critical for the development of new medical information and techniques.

A healthy lizard is curious, alert, active, and hungry. When stimulated, it stands up on its front feet, lifting its entire under-side off the ground.

One reason bearded dragons have become so popular is that they are personable and animated. Unlike certain snakes that spend a considerable amount of time wrapped up and vegetating contentedly, bearded dragons are active and entertaining. Each dragon has a unique personality and unique behavioral patterns, which are important for owners to evaluate during their normal caretaking duties. Simply put, sick children look sick, sick dogs look sick, sick cats look sick, and sick bearded dragons look and act sick. If, as an owner of a bearded dragon, you have missed the foot-stomping, arm-waving, tail-swishing, head-bobbing, sideways head tilts, and various other gymnastic techniques that bearded dragons use to communicate their feelings, resolve to watch more carefully in the future.

The most common signs of a sick bearded dragon are listlessness, inactivity, lying flat (instead of raising the body when standing), failing to eat or drink, and lack of normal communicative body language. In short, they are depressed and won’t eat. Do any of these actions, or the lack thereof, indicate a particular disease or ailment? Unfortunately, they do not. These symptoms can be noted in all of the serious yet common bearded dragon ailments discussed here.

A sick bearded dragon is typically sluggish and listless, eating very little if anything. This juvenile dragon was diagnosed with coccidiosis, and initial treatment consisted of fluid therapy and force-feeding followed by the use of a sulfa drug.

Coccidiosis is the most common disorder seen in bearded dragons. Coccidia are microscopic, protozoan parasites that live primarily in the small intestine and replicate in the lining cells of the intestinal tract. The end product of the reproductive process is a microscopic entity called an oocyst. These tiny oocysts are passed into the environment with the feces when the bearded dragon has a bowel movement. The oocysts can then reinfect the host by being ingested. If your bearded dragon is anything like Lily, my daughter’s bearded dragon, this happens frequently. Lily stomps through her waste as if it were put there for her entertainment. She then proceeds to stomp through her water dish and veggies, potentially contaminating the food and water with oocysts as she goes. Crickets and mealworms loose in the cage also crawl through or munch on the evacuated bowel materials. The crowning moment is when Lily takes a little nibble at her own stools, which is not an abnormal behavior. This is a direct life cycle at work; no intermediate hosts are required. One coccidium becomes a dozen, twelve coccidia become hundreds, and so on.

Coccidia are so prevalent in bearded dragons that they have their own species of coccidia—Isospora amphiboluri. Since almost all bearded dragons in captivity have coccidia, maybe the parasites are normal inhabitants. I have never seen data that evaluated the parasites of wild bearded dragons. Perhaps some of the first founding stock of bearded dragons brought into the U.S. were inadvertently exposed to coccidia. In any case, I take the stand that regardless of the source, coccidia should be eliminated whenever possible for the following reasons:

1) The parasites have a direct life cycle and build up to tremendous levels in captive animals. This is known as a superinfection.

2) Coccidia invade the intestinal lining cells to reproduce. In large numbers this can lead to gastrointestinal pain, diarrhea, malabsorption, and fluid loss. Eventually, this can lead to a failure to eat, weight loss, secondary nutritional disorders, and secondary bacterial infections.

3) Hatchling bearded dragons appear to pick up coccidia even when not exposed to the environment of the parent. This would infer transuterine or egg-related transfer. At some point we must break this cycle.

4) The coccidia may be transmissible to other reptiles. While coccidia are somewhat host specific, there have been no studies that I am aware of to determine whether I. amphiboluri affects other reptiles. I would be willing to bet that they do so quite readily.

So how do we get rid of coccidia? It’s not easy, and it’s not fun. Due to the lack of research on anticoccidial drugs for many decades, there are mainly two old standby sulfa drugs—sulfadimethoxine (Albon) and trimethoprim-sulfa (from many manufacturers). These drugs should be obtained from your reptile veterinarian only after a diagnosis of coccidiosis is confirmed with a fecal examination.

The protocol I use for eliminating coccidia was developed during an in-depth bar chat with two esteemed colleagues, Drs. John Rossi and Richard Funk. We shared information on treatments that, while reducing numbers, failed to eliminate all coccidia. We decided that using sulfa drugs resulted in the same outcome. I prefer giving oral sulfadimethoxine daily for three to five days, then every other day for as long as it takes. The secret to eliminating this disease resides in environmental control. You have to pretend that you are an obsessive/compulsive cage cleaner; and if you already are, then that’s even better. To have a chance at breaking the exposure cycle with coccidia, the cage must be reduced to the bare essentials. Use newspaper or paper towels on the floor of the cage. Change the cage at least once or twice daily. Don’t try to clean branches and rocks with cracks, crevices, or holes. Throw them out. Use cardboard cage furniture that you can eliminate daily. Water dishes should be simple and cleaned thoroughly twice every day.

Maintain the use of heat lamps and undercage heaters. Eliminate hot rocks and replace them with an undercage heater.

Feeder crickets, mealworms, wax worms, or veggies that are not eaten in a twenty-four-hour period should be eliminated. Do not recycle them or save them to use with other reptiles. Remember, the insects may have dined on the dragon droppings and would only serve to perpetuate the cycle.

Dr. Funk prefers having two side-by-side cage setups where one cage is always clean. Simply switch the bearded dragon to the other cage and clean the old one. Switch as often as necessary to decrease the possibility of exposure to fecal material and therefore coccidia oocysts. Sound like a pain? It is, because it has been my experience that it will often take up to six weeks for treatment to be successful. Even then, run a follow-up fecal exam two to three weeks after stopping the treatment protocol. Make sure your lizards are coccidia-free before mixing and matching dragons.

Treating a large group of bearded dragons in such a manner is obviously difficult, if not impossible. This regimen is a nuisance to practice for two lizards, much less two hundred! I’m quite pessimistic that breeders with large numbers of dragons will take the steps required to eliminate their lizards’ coccidia until more practical anticoccidial products are introduced. Not only would the lizards need to be separated as much as possible but outdoor enclosures would have to have dirt and other materials replaced. The good news is that once the group is clean they will stay that way unless new coccidia-bearing dragons are introduced. Studies are currently being conducted on new anticoccidial drugs for use in bearded dragons (with the cooperation of large dragon ranch operators such as Bob Mailloux at Sandfire Dragon Ranch), offering true hope that coccidia will someday be a thing of the past.

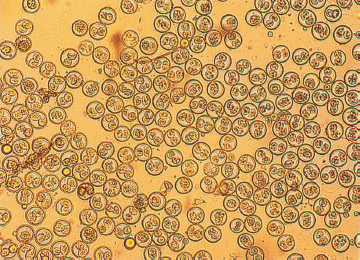

Note the hundreds of coccidial oocysts (100X) from a portion of bearded dragon stool.

Remember the importance of quarantining new animals. I personally have seen dozens of coccidia-free groups of bearded dragons that were reinfected by the premature addition of a new arrival. New additions should be isolated for at least a few weeks and have fecals run on at least three samples over a period of weeks before being judged to be parasite-free.

A word of warning: Sulfa drugs should not be indiscriminately administered to every sick bearded dragon and should be used only if coccidia have been diagnosed. Sulfa drugs are potentially dangerous to dehydrated reptiles and need to be used under expert supervision. Rely on your reptile veterinarian for diagnosis, prescription of medications, and performance of follow-up fecal examinations.

Pinworm ova and coccidial oocysts at 400X.

One last word about coccidia: I’d like to dispel the myth that coccidia oocysts are fragile. As a veterinary student, I was taught that oocysts are so fragile that it would be difficult to diagnose coccidia in some species due to the spontaneous decomposition of the thin-walled oocysts exposed to different drying and osmotic gradients. We should be so lucky! It has been my experience that oocysts can be found in petrified bearded dragon droppings, and they don’t appear fragile in the least. I have placed various reptilian coccidial oocysts in 2–10 percent formalin to pickle them for later study, only to find out that some of the oocysts had continued their development! So clean your cages thoroughly with a soapy water/bleach solution (1 part bleach to 30 parts water). If the oocysts are not outright destroyed (the vast majority will be), then they will be removed mechanically.

Pinworms are another group of parasites that are ubiquitous in bearded dragons. While considerably less harmful than coccidia, pinworms can reach tremendous parasitic loads due to their direct life cycle.

While the treatment of pinworms is somewhat controversial (see, for example, Klingenberg 1997), my feeling is that any parasite capable of creating superinfections should be eliminated. Pinworms are easily eliminated by administering oral fenbendazole (Panacur) daily for three to five doses, repeating this regimen again in ten days. Follow-up fecals should be checked three weeks after the last treatment.

Dr. Elliott Jacobson recently reported the first cases of this intracellular protozoan parasite in three bearded dragons that had been inappetent and depressed, and that eventually succumbed to the protozoan parasites. While known to infect some amphibians and other reptiles, microsporidia had not been previously reported in bearded dragons.

These obligate intracellular unicellular protozoans are important pathogens of invertebrates and it was speculated that feeder insects were the source of infection, which is unlikely. The main source of transmission is probably spores shed from infected reptiles. While uncommon, this is a parasite that reptile veterinarians will be watching for in the future. It possesses characteristics that reptile owners and veterinarians dislike—a direct life cycle and resistant spores that can persist up to a year in the environment.

While rarely diagnosed, I suspect that tapeworms are more common than is currently recognized. Tapeworms should be considered in bearded dragons that have been treated for coccidia and pinworms yet don’t gain weight despite ravenous appetites,. An analogous situation was seen in ball pythons that had trouble gaining weight despite good appetites and appearing otherwise healthy. Occasionally these animals have been treated for tapeworms despite no definitive proof of their presence. Such a course of treatment should be based on discussions with a reptile veterinarian who knows the overall health parameters of the bearded dragon in question.

The most common means of diagnosing tapeworms is by the presence of tapeworm segments (proglottids) in the feces. Proglottids are small, white, rice-shaped segments that can be found on the surface of the feces or moving away from it. These segments contain tapeworm eggs to be distributed to the environment either by desiccation of the segment (thereby releasing the eggs) or by being ingested. Tapeworm eggs can be found on routine fecal flotations but seem to be present only in very heavy infestations.

The flat, white rice-shaped objects in this bearded dragon’s stool are tapeworm proglottids.

Treatment consists of either an oral or injectable dose of praziquantel (Droncit), which is repeated after two weeks. Tapeworms require intermediate hosts and have indirect life cycles, so self-exposure is not the problem it is with coccidia or pinworms.

Dr. Charlie Innis was kind enough to send a fecal sample from an individual bearded dragon he was treating that was diagnosed with pentastomids. This was the only case I had heard of until running across a book on bearded dragons and frilled lizards written by Hauschild and Bosch (2000), which stated necropsies performed on ninety-three bearded dragons yielded eleven with pentastomids.

Pentastomids have an indirect life cycle, requiring intermediate hosts such as insects and rodents to complete their reproductive cycle. Extensive larval migration occurs before adults form in the lungs and complete the cycle by laying eggs that are then passed through the feces and into the environment. Despite large numbers and extensive larval migration of these prehistoric caterpillar-like parasites, most infestations occur without major symptoms. In some cases, there can be damage to the tissue during larval migration or when adults are in the lungs.

Treatment to date has been with high doses of ivermectin (Ivomec) which Dr. Innis has thus far found to reduce the number of ova passed but has not stopped the shedding altogether. His clinical trial wasn’t completed at the time of this writing.

Pentastomids pose an unknown zoonotic risk and owners should be informed of this if their bearded dragons are affected. This is not a parasite I would take home to Mom.

Mites are not common, but when they do appear, they seem to be acquired from other reptiles within a collection. Mites do not appear to be indigenous to bearded dragons. Snake mites will infest bearded dragons and can be seen crawling on the lizards with the naked eye.

As with all mite infestations, treatment begins with the environment. At least temporarily, change the substrate to newspaper to eliminate hiding and breeding spots for the mites. Change the paper substrate at least two to three times a week. Reduce cage furniture to a minimum and eliminate all rocks or branches with cracks and crevices. An initial cage cleaning with a mix of water and bleach (one capful of bleach to each gallon of water) helps to mechanically eliminate mites and their eggs.

My preferred method of treating mites is to use an ivermectin-based spray (5–10 milligrams of ivermectin per quart of tap water). This solution is sprayed liberally in the cage after a thorough cleaning, with the lizard and water dish removed until the cage is dry. The lizard is gently but liberally sprayed, including the face and eyes, and returned to its dried cage. The water dish can be replaced once the cage and the lizard are thoroughly dried. This spray needs to be used every four to five days for three weeks. Ivermectin is not a quick-kill product, so you may continue to see mites moving for the first few days of treatment. Store the spray in a dark cabinet between treatments and mix a new batch every thirty days.

For large, outdoor enclosures, I recommend removing the lizards to smaller indoor cages for individual treatment with the above ivermectin spray, while the outdoor enclosures are sprayed with a pyrethroid (type of insecticide) product designed for flea control in dogs and cats. The lizards should remain off the sprayed area until it has completely dried. If possible, it is ideal to keep the lizards in indoor cages while they are treated, but if they must be returned to the outdoor enclosures the lizards should remain off the sprayed areas until drying is complete. Most of the toxicity of pyrethroids has been linked to respiratory exposure in nonventilated containers, so a pyrethroid spray used as instructed in an open-air enclosure should be relatively safe. Pyrethroid has residual action and, depending on the product, need only be applied every one to three weeks. The dragon should be sprayed with the ivermectin product every four to five days for three weeks. Due to numerous hiding places and other variables, mites may be difficult to control in outdoor enclosures.

One of the great benefits of being a reptile owner is that you get to observe feeding behaviors. Bearded dragons are just plain cool to feed. A healthy, hungry bearded dragon will perform an Olympic-quality floor exercise while polishing off a dozen crickets, mealworms, or wax worms. It is so much fun to feed insects to bearded dragons that sometimes that is all people feed them. As often as not, the dragons are so satisfied with their crickets that they refuse to eat vegetable matter. However MacMillen, Augee, and Ellis (1989) report that, in the wild, vegetable matter makes up as much as 90 percent and 50 percent of the diets for adult and juvenile bearded dragons, respectively.

Greens and veggies are important sources of fiber, vitamins, and other nutrients.

Greens and veggies are important sources of fiber, vitamins, and other nutrients.

Availability of produce food reduces intraspecies mutilations.

Availability of produce food reduces intraspecies mutilations.

Crickets and other invertebrate prey can also gut load on the salad, prior to being eaten.

Crickets and other invertebrate prey can also gut load on the salad, prior to being eaten.

Reducing the overall dietary protein and fat while increasing vegetable intake may extend longevity.

Reducing the overall dietary protein and fat while increasing vegetable intake may extend longevity.

Keep in mind, though, that even when greens and veggies are fed along with crickets and other insects, nutritional disorders may occur.

Keep in mind, though, that even when greens and veggies are fed along with crickets and other insects, nutritional disorders may occur.

The most common nutritional disorder I’ve seen in bearded dragons is calcium deficiency in the form of hypocalcemia (low blood calcium). The most common cause is a diet of almost exclusively crickets. Most feeder crickets come straight from a pet store and are not fed balanced diets (gut loaded) or dusted with nutritional supplements prior to being fed to dragons. Calcium deficiency is also seen in bearded dragons fed excessive amounts of meat products. These diets are low in calcium, and less calcium in the dragon’s body leads to stimulation of receptors in the parathyroid gland, which in turn causes the release of parathyroid hormone (PTH). Increased levels of PTH activate cells in bone (osteoclasts) to start demineralizing bone to release calcium into the blood stream.

If the primary problem presents as soft bones and multiple fractures, the dragon’s disease is termed metabolic bone disease (MBD). If the primary problem is twitching and seizures, then the dragon likely suffers from hypocalcemia (which is more common in juvenile dragons). Both forms are caused by too little calcium in the diet.

The other main source of calcium deficiency I’ve seen in practice is vitamin D3 deficiency or hypovitaminosis D. This fat-soluble vitamin is essential to the uptake and utilization of calcium in the body. Bearded dragons produce much of their vitamin D3 from the reaction of UV light on their skin. This converts a cholesterol-derived product from pre–vitamin D to active vitamin D3. The synthesis doesn’t occur in dragons housed indoors without exposure to UV-B. (See the chapter on heating and lighting for information on UV-B, sunlight, and UV-B-emitting bulbs.)

Muscles require calcium to contract properly. Calcium deficiency leads to muscle pain and dysfunction such as when the smooth muscle of the gastrointestinal tract won’t support peristaltic waves and results in constipation. Sometimes the first signs seen in young calcium-deficient dragons are bloating and constipation.

When the calcium level has been low for an extended period, muscle tremors set in. Toes and feet begin to twitch. This calls for immediate calcium supplementation.

As a bone is demineralized by the PTH-driven osteoclasts, the bony matrix is fortified with fibrous tissue (termed fibrous osteodystrophy), resulting in a brittle, swollen, and painful bone.

Calcium-deficient dragons initially look like any sick bearded dragon—weak, depressed, and reluctant to move. Very young dragons may be tremendously bloated and uncomfortable. Occasionally, twitching of toes and limbs is noted prior to handling. Sometimes twitching won’t become evident until the lizard is stressed by handling. It has been my experience that hypocalcemic tetany, or twitching, appears in bearded dragons prior to extensive bony changes such as swollen limbs and softened jaws (rubber jaw). This is in contrast to green iguanas and other lizards, which may suffer extensive bony damage prior to muscle tetany.

Bearded dragons with signs of calcium deficiency should be treated right away. Supplementation with calcium is initiated immediately. I prefer to use Neo-Calglucon, an oral product for humans, as my first source of calcium because it seems to be better absorbed than other products. Then review diet and husbandry to see if a vitamin D3 injection is justified. Constipated animals are given gentle enemas or have their bowels emptied mechanically. Supportive care in the form of fluids and involuntary feeding is employed until a dragon is well enough to start eating its corrected diet. Some dragons are so weak that attempting oral calcium, fluids, or foodstuffs could easily result in aspiration pneumonia. Even the most debilitated lizard can have a pharyngostomy tube (placed by a qualified veterinarian), through which you can give medications, fluids, and food.

This adult bearded dragon has a deviated, or crooked, tail-base as a remnant of fibrous osteodystrophy. The dragon responded rapidly to calcium supplementation, UV-B, and a corrected diet and suffers no ill effects from this mild deformity of its tail.

As with most diseases, calcium deficiency is best prevented rather than treated. The reader should review the sections in this book on husbandry and diet. Certain strategies are emphasized here.

It is essential to expose young bearded dragons to a wide variety of vegetable matter so they get used to eating these foods and consume them as part of their usual diet. Some young bearded dragons enjoy vegetable human baby food into which small quantities of calcium can be stirred. For calcium supplementation, I suggest using calcium carbonate (no phosphorus or vitamin D3), which can be obtained from health food stores or can be purchased as Tums antacid tablets. I tend to dust veggies and/or crickets two or three times a week for young, growing dragons.

This juvenile bearded dragon was treated with Neo-Calglucon syrup, which led to excess residual syrup on its chin and predation by hungry crickets. Be aware that insect prey can be-come hunters instead of the hunted.

For provision of vitamin D3, I employ two sources: a UV-B bulb and a powdered supplement. I place the bulb on the enclosure’s screen top within 12 inches of the dragons and leave it on for twelve to fifteen hours in the summer and for ten to twelve hours in the spring and fall. I select the bulb carefully because only a few on the market produce significant levels of UV-B. I replace the bulb every six to nine months to ensure adequate UV-B production. In addition to the bulb, I use a powdered supplement that contains calcium and vitamin D3, dusting it onto food no more than once every two weeks. Vitamin D toxicity is a real concern. It can easily be acquired through the use of products containing high levels of vitamin D3 at every dusting. Calcium has one of the most narrow safety margins of all nutrients, and can produce signs of disease when fed in excessive amounts.

At this time, I’m not using a multivitamin product because I feed my dragons a broad range of veggies and gut-loaded insects that contain adequate nutrient content. If a multivitamin product is used with bearded dragons, it should be offered only once every two weeks. Use good food, supplements, UV bulbs, and common sense!

Force-feeding is very important in treating calcium-deficient dragons. Here a client uses a 1 cc syringe to feed her juvenile dragon a mixture of a vegetable-based baby food to which she has added a pinch of calcium carbonate powder and a little Pedialyte for fluids and electrolytes.

Adenovirus disease in bearded dragons is poorly understood for the same reason most reptile diseases are poorly delineated—lack of funding for critical research. Here’s what we do know.

Unfortunately, there are no specific signs to watch for in bearded dragons sick with adenovirus. Most of the bearded dragons that have been diagnosed with adenoviruses have had a history of failing to thrive, sometimes showing poor appetite, sometimes exhibiting diarrhea. Sometimes they die. The young, especially those four to twelve weeks old, appear to be affected more often than older specimens. Rather vague, wouldn’t you say?

An affected animal is typically difficult to differentiate from one with coccidiosis or certain forms of calcium deficiency. To further complicate matters, dragons can have multiple disorders. A young bearded dragon with adenovirus could also have coccidiosis, which may or may not be causing problems at that moment. This young dragon could, or would, certainly develop nutritional disorders including hypocalcemia as poor food intake becomes a factor. These mix and match illnesses could go on and on, with one factor affecting another or making no difference. It’s important to know if adenovirus is present in a sick dragon, but how do we accomplish this task?

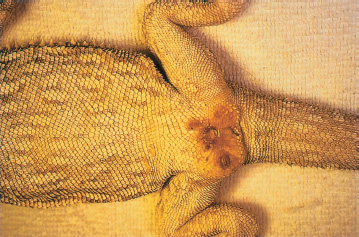

The only method currently available to diagnose adenovirus is autopsy. Most dead bearded dragons fail to demonstrate significant gross (readily visible) abnormalities of the internal organs. It is only on examination of tissues and cells with a microscope that the presence of intranuclear inclusions (material characteristic of certain viral infections), primarily in necrotic (dead) areas of the liver, is found. Such inclusions are presumptive evidence of adenovirus, but electron microscopy is required to confirm the diagnosis by demonstrating typical viral particles. This is not the same inclusion body disease that afflicts boids and pythons. Both are viral diseases but entirely different groups of viruses. The only similarity would be to make the suggestion that a liver biopsy is a useful diagnostic test, prior to the bearded dragon’s death. While it may be somewhat risky to perform a surgical biopsy technique on a sick bearded dragon, the information obtained from liver biopsies is invaluable. A quick surgical biopsy on a living dragon is always preferable to a necropsy on a dead one.

This necropsied specimen with adenovirus illustrates a large liver that could have been accessed ante-mortem by a minor abdominal incision.

While the technology exists to produce a simple blood test, this won’t happen until it is demanded by you, the bearded dragon owner and veterinary client.

So do all bearded dragons exposed to adenoviruses die? No, some become chronic “poor doers” that come around slowly but can eventually recover, or at least appear to recover. Supportive care techniques—including force-feeding, fluids, and occasionally administrating antibiotics for secondary infections—increase their survival rate.

No one knows how long a bearded dragon that has recovered from adenoviruses carries and sheds the virus. And while we suspect the virus is given from one sick reptile to another through fecal and oral exposure, we truly don’t have all the answers. So, whether you have a small group of pets or a large breeding colony, a virus severely complicates things. While there is always the risk of death, there is also the risk of spreading the disease by selling or trading the original lizards or their offspring. In essence, a diagnosis of adenovirus within a group of dragons should make them a closed group, with no additions or subtractions from the infected group. If future studies were to show that recovered lizards shed the virus for six weeks (this is hypothetical, not a fact!) and then fully recover, then an owner could quarantine an infected group for a reasonable time with hopes for the future. If studies reveal that infection and shedding is a lifelong phenomenon, then an owner would know that sick animals could never be moved from the group. This should clearly illustrate the need for basic research to answer such practical questions.

Water is extremely important to the elimination of nitrogenous waste products in all reptiles. Because bearded dragons originate in the red sand deserts of Australia, it used to be assumed that bearded dragons have durable kidneys. Most desert-dwelling reptiles have adapted to extremely dry conditions by developing mechanisms to preserve water and to excrete concentrated uric acid. Apparently we haven’t discovered or appreciated the methods employed by bearded dragons, because evidence of renal disease is on the rise.

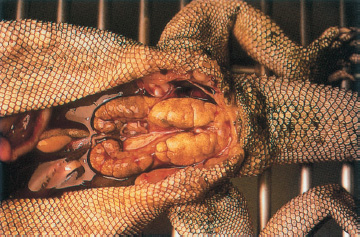

Hauschild and Bosch (2000) stated that a group of necropsies on ninety-three bearded dragons revealed that 30 percent of the specimens had primary and secondary visceral gout. We need a very brief review of gout. As mentioned previously, the nitrogenous waste product that bearded dragons must eliminate from their blood stream is uric acid, which is a highly insoluble product. If the kidneys become damaged by age, drugs, and chronic dehydration, they will be unable to properly filter out uric acid, which will increase in the bloodstream. If the resulting hyperuricemia becomes extreme, uric acid crystals are deposited into internal organs, causing severe inflammation and sometimes organ failure. The deposit of uric acid into tissues is often referred to as gout, and when this involves the internal organs it is called visceral gout. Deposition of uric acid due to kidney damage is termed primary visceral gout. If the kidneys are not damaged initially and dehydration leads to the hyperuricemia and deposits of uric acid, it is referred to as secondary visceral gout.

Fluids are the most important initial treatment in cases of kidney failure. This bearded dragon is receiving an injection of fluids into the coelomic cavity.

Visceral gout is usually fatal in bearded dragons unless corrected very early in its course. It is not yet known whether the visceral gout is primary (kidney damage) or secondary (dehydration). Some experts have speculated that wild bearded dragons retreat to moist underground burrows or stay buried to prevent loss of fluids. In the wild, adult bearded dragons appear to eat mainly vegetation, which can be a major source of moisture. Our hope is that husbandry factors such as excessively dry substrates, basking under a heat lamp, and a lack of moist veggies are the cause of dehydration, because these can easily be corrected.

Kidney failure due to excessive calcium and vitamin D3 administration is common in other lizards, particularly the green iguana. The presence of excessive D3 leads to the uptake of excessive calcium and subsequent mineralization of the kidneys. This syndrome hasn’t been reported in bearded dragons, but it may just be a matter of time before we see it.

Mild dehydration should always be corrected in any sick dragon. A dehydrated dragon may receive a sub-cutaneous injection of fluids.

I hope further research on this topic will find some simple husbandry practices to help maintain captive specimens with normal kidneys. If diagnosed early, treatment centered around fluid therapy can be initiated and husbandry practices reviewed.

Prolapses are not common in bearded dragons, but they do occur, and should be treated as a relative emergency. The most common type seen in practice is hemipenal prolapse after breeding. The prolapsed hemipenes is a relatively large (3/4 inch long by 1/4 inch wide) bright red to dark red mass protruding from the vent of the affected male. The treatment is to gently clean and lubricate the tissue and then gently push it back into the vent with a lubricated Qtip. The problem is that by the time this problem is noted, the tissue is often quite inflamed and swollen and cannot be replaced without it popping back out. If the tissue becomes excessively swollen, begins to dry out, or is traumatized by being dragged around the cage, the hemipenes’ vascular supply could become damaged, necessitating an eventual amputation.

The abscess in the hemipenal region of this adult male bearded dragon was noted after the dragon had become lethargic and stopped eating. The source of the abscess is unknown, but the condition responded well to gentle debridement, topical antibiotic ointment, and a systemic antibiotic.

Due to the fact that so many variables exist with prolapses, the ideal course of action is to have your reptile veterinarian examine the dragon right away. The tissue can be evaluated for viability and sutured to help the hemipenes stay in place. Another important consideration is that some prolapses are of rectal tissue, which may be much more difficult to identify correctly. These prolapses are even more important to handle promptly and correctly. A bearded dragon can live without a hemipene, but it can’t live without a functional rectum.

Rectal prolapses are often the result of chronic straining, so any dragon who is straining should be evaluated for parasites (such as coccidia, pinworms), gastrointestinal infections, constipation, gastrointestinal obstructions, and, in females, egg-binding. In addition, rectal prolapses can recur if their underlying cause is not identified and corrected.

Review the chapter on reproduction if there is any chance your female dragon could be gravid (or pregnant). A basic understanding of the bearded dragon reproductive cycle is helpful when dealing with problems. A gravid female is usually easy to detect, as her abdomen is swollen and her body weight increased. She looks pregnant. If the dragon is allowed to crawl across your open palm with your fingers slightly elevated, you can often feel the grape-sized eggs in her lower abdomen.

The cloacal abscess in this female adult bearded dragon may have resulted from a substrate made up of excessively abrasive rocks. Abrasions from “rub sores” became infected and weren’t noticed until quite advanced.

Behaviorally, pregnant dragons often continually dig and squat, move to a new spot and try again. They are agitated and tired, and usually won’t eat properly due to both discomfort from the egg mass and the anxiety associated with egg-laying.

The easiest thing to try for an anxious lizard that appears ready to lay eggs and can’t is to make sure the egg-laying site is appropriate. In the event that a bearded dragon is continuing to have problems, see a veterinarian right away. One of the most common problems is muscle weakness associated with subclinical calcium deficiency. The dragon’s calcium isn’t low enough for her to show other outward signs but is low enough to interfere with muscle contraction in her oviducts. Some dragons may be weakened by concurrent problems with parasitic, nutritional, viral, or bacterial diseases. This isn’t a time to wait and see what happens without taking a great risk with the female’s life. It is most important to make a diagnosis and try to correct so that eggs are laid successfully. In some cases, surgery might be necessary to save the female.

When compared to other groups of lizards, members of the genus Pogona tend to be rather resistant to respiratory infections. Nonetheless, prolonged exposure to temperatures that are marginally cool but not quite cold enough to induce brumation can result in respiratory infections. The most obvious symptoms of respiratory infections are gaping, forced exhalation of air, puffing of the throat, and a puffed-up appearance of the body. In severe cases, mucus will accumulate in the mouth and may emerge from the nostrils.

The rectal prolapse in this bearded dragon was associated with an extremely heavy load of pinworms. Prolapses should be considered an emergency.

Remember that bearded dragons are desert dwellers. In mild respiratory infections, keep the animals at higher temperatures with daytime highs in the upper 80s to low 90s to allow immune system stimulation, enabling the lizard to fight off the infections. If the symptoms persist or worsen, take the animal to a reptile veterinarian for antibiotic therapy. De Vosjoli reports intermittent gaping behavior in heavily parasitized lizards and also in overheated bearded dragons. Respiratory disease is most often associated with subnormal temperatures.

Veterinarians across the country have noted that bearded dragons are prone to developing swollen and runny eyes. A common hypothesis for this condition is that dust from sandy substrates is irritating, setting up an inflammatory conjunctivitis that is soon complicated by infections. This is somewhat puzzling as bearded dragons originate primarily from the red deserts of Australia where they are certainly exposed to a bit of sand. In any case, unprocessed silica sands and calcium-based sand products can certainly produce profound irritation if a few particles become trapped behind the third eyelid. Most of these problems respond nicely to a temporary change of substrate to newspaper for a couple of weeks while applying an artificial tears ointment or eye drop two to three times daily. The drops and ointment hydrate the eye and allow small particles to be flushed out.

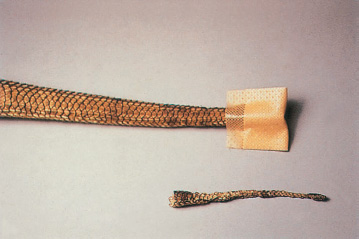

Tail Rot

FAQ: I now have had several bearded dragons whose tail tips have darkened. This eventually spread and part of the tail was lost. What causes this?

The popular term for this kind of tail loss is tail rot. It is usually attributed to two causes. The first is trauma, such as an injury from nipping or from being crushed or compressed by landscape materials. The other is accumulating tail tip sheds.

The first step should be to dip the damaged tail in a hydrogen peroxide solution as soon as it is noticed. This softens adhering shed skin, allows for its removal, and helps nip infection in the bud, so to speak. Dipping the tail in Betadine also works against infection and prevents the spread of tail rot. If this doesn’t work, consider seeing a qualified reptile veterinarian. The best weapon against tail rot is prevention: keep babies segregated and well fed, making sure there are no landscape structures that can cause trauma to the tail, and soak bearded dragons in shallow water dishes to soften adhering shed skin.

In resistant cases, an ophthalmic antibiotic drop or ointment may be indicated for an infection. However, some veterinarians are reporting that some dragons still have eye problems, even with substrate changes and aggressive topical treatment. Other potential causes include allergic, nutritional, traumatic, or viral infections. I had one refractory case that did not go away until the animal was sedated and the inner layer of the third eyelid scraped, which suggests some type of foreign body was causing the problem.

Parts of tails and digits of juvenile bearded dragons are sometimes nipped off by cage mates. Unlike in many other lizard species, caudal autonomy, or the dropping of part of the tail is not part of the defensive repertoire of these species. Once lost, neither tail nor digits will grow back. Fortunately, infections seldom develop following these cannibalistic snacks.

Sandy substrates are often the cause of swollen and sore eyes. They respond to flushing with artificial tears. Difficult cases should be taken to a veterinarian.

Obviously they are not. However, bearded dragons are hardy lizards and in no way am I trying to discourage a potential owner from pursuing the opportunity to own and care for one or several dragons. My family’s bearded dragon is the easiest lizard we’ve ever had. These lizards are extremely entertaining and gentle, one of the best lizards for hands-on activities.

Purchase your dragon from a reputable source. All new dragon owners should have their lizards examined by an experienced reptile veterinarian. At the very least you need to have fecal examinations performed—if your veterinarian doesn’t suggest this then he or she is doing you a disservice. Eliminate any and all parasites. Quarantine (for parasites and viral diseases) any new bearded dragons for a minimum of two to three months. If you own a group of bearded dragons and one dies, refrigerate it until it can be necropsied by your reptile veterinarian.

I’ve covered the most common diseases of bearded dragons. Other diseases occur too, albeit less frequently. Dragons may also require surgery for such problems as broken bones, bite wounds, and placement of drains or feeding tubes. Today’s dragons may receive CAT scans and laser surgeries, and may be examined with ultrasound and endoscopes. If your dragon becomes ill, find a veterinarian who enjoys dragons and is experienced in the medical and surgical care of reptiles.

Unlike many other lizards, the tails of bearded dragons do not regrow after removal. The tip of this bearded dragon’s tail was carelessly pinched in the lid of its cage.

This necropsied specimen died from visceral gout secondary to kidney failure that may have been initiated by sulfa drugs, which are generally safe but can cause renal damage. These kidneys are two to three times normal size because the body tried to compensate for increasing damage due to uric acid deposition.

The following health chart will help you determine whether your dragon needs veterinary care or other treatment for common symptoms.