CHAPTER TWELVE

Active Qigong

“Is Taiji Quan practice the reason for your longevity?”

“Not directly. Taiji Quan helps cultivate a relaxed spirit. Having a relaxed spirit is the secret of longevity.”

—INTERVIEW WITH 105-YEAR-OLD TAIJI QUAN MASTER WU TU-NAN

In China, the word “qigong” calls to mind an image of thousands of individuals gathered in a park at dawn, imitating a master’s graceful postures. Although meditative qigong is easier to learn and practice on one’s own, active or dynamic qigong, dong gong, is the more popular form. There are two likely reasons for this. Firstly, active qigong is a social event; learning it requires participating in a class. This means making new friends and being inspired by the example of teacher and classmates to reach for excellence. Secondly, the skills and body awareness acquired through active qigong can be more easily applied to sports or the martial arts. Indeed, many Chinese martial arts are considered styles of qigong. Learning to breathe properly, stand straight, and root into the ground, the student develops a stronger punch and healthier qi.

As we shift toward an ever more sedentary lifestyle, as computers and modems replace human interaction, active qigong becomes increasingly necessary. In any case, most qigong practitioners are frankly unconcerned about why they practice. They might begin practicing qigong because they need the exercise or wish to improve their health. Once they try it, they are hooked. They practice because qigong is fun, and it feels good both during and after practice.

It would be pointless to try to catalogue the thousands of styles of active qigong. Instead I will describe the foundation techniques of the great, classical systems of active qigong. These are relatively few in number. What do I mean by “classical systems”? Styles that are referred to again and again in histories of qigong in the Chinese language. I advise learning these techniques first, since they are excellent time-honored self-healing techniques. Learn the theme before learning the variations. Once you learn the classic systems, you will be able to more accurately assess the benefits and evolution of other styles. Learning the classical qigong styles is like learning arithmetic before algebra or becoming a general practitioner before studying a specialized branch of medicine. Without this foundation, the student is easily confused by complex forms or recent innovations.

In this chapter I describe techniques that can be practiced safely and accurately without a teacher’s physical demonstration and coaching. However, there are some qigong methods that cannot be learned from a book, and I will not fool the reader into thinking that I can accomplish the impossible. If you do not have access to a qigong instructor, a video can be a helpful way to continue your progress. (See Qigong Resources at the back of this book.)

Any qigong instructor who has done his homework (practice, practice, practice!) can teach valuable qigong techniques. Students should not presume that the styles I present here are the only orthodox or correct procedures. They simply represent the methods that I have found most effective in my own practice and research. I am grateful that other instructors may do things differently. It means we can learn from each other.

Review various styles according to your time, interest, and needs. If a style is improving your health, concentrate on that style. Do not try to practice all systems of qigong in any one session. It is best to spend from twenty to forty minutes in daily morning training. You may wish to alternate styles on different days. Or you can spend a few months on one or two systems, then switch to another. After going through the whole course, you can determine which kinds of qigong are most appropriate. In Chapter 16 I will describe how to combine styles to create a balanced morning workout.

During all active qigong exercises described below, the eyes are always open, with a soft, relaxed gaze. All breathing is through the nose, unless otherwise noted. The joints are never locked, even in stretching postures, because locking a joint blocks the qi.

THE EIGHT BROCADES

Ba Duan Jin means literally “Eight Pieces of Silk Brocade.” These eight exercises are elegant, graceful, and essential methods of qi cultivation. They were first described in an eighth-century Daoist text, Xiu Zhen Shi Shu (The Ten Treatises on Restoring the Original Vitality), in the Daoist Canon. Daoist tradition attributes the exercises to one of the Eight Immortals of Chinese folklore, Chong Li-quan. Chong is frequently represented in Chinese art as a bald-headed, potbellied figure, with a white beard reaching to his navel. Chong had been a general during the Han Dynasty. When his army was defeated in a battle against Tibetans, Chong withdrew into the mountains rather than face the Emperor’s wrath. There he met a Daoist who transmitted to him dao-yin (qigong) “recipes” to create an inner elixir of long life. The Eight Brocades was one of these methods. Before he died, Chong inscribed the exercises on the walls of a cave. When another general, Lu Dong-bin, discovered this cave several centuries later, he followed the diagrams and also became a sage-Immortal. According to a statement in the Ten Treatises, it was General Lu himself who first inscribed the exercises on stone.

The Eight Brocades are a good way to start a workout. They consist of gentle stretching exercises that lengthen the muscles and tendons and stimulate the meridians and internal organs. There are both seated and standing varieties of the Eight Brocades. The method I teach is similar to the standing set described in Illustrated Explanation of the Eight Brocades by Wang Huai-qi.1 The movements should be done fluidly, but brusquely. Not too fast, not too slow. Find a comfortable pace. I like to repeat each about nine times, though there is no strict rule. Breathe only with the nose.

1. Two Hands Reach Skyward to Balance the Triple Burner

This simple arm stretch gently elongates the body and balances the metabolism of the Three Burners: the upper, middle, and lower body.

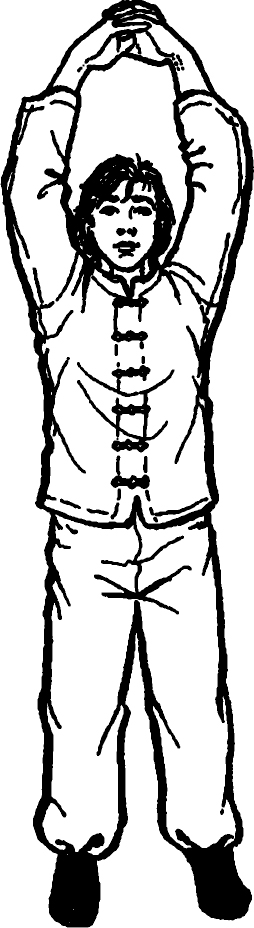

Stand in qigong posture. The arms circle overhead. Interlace the fingers and as you inhale stretch them upward, with the palms facing down. At the same time rise up on the toes (fig. 20). As you exhale, the feet rest flat on the ground and the interlaced hands rest for a moment on the crown of the head (fig. 21). Then stretch upward again, inhaling, rising on the toes, this time with the palms facing up (fig. 22). Exhale, again the palms rest on the crown, the feet flat. Repeat several times, each time alternating the direction of the palms.

2. Open the Bow as Though Shooting the Buzzard

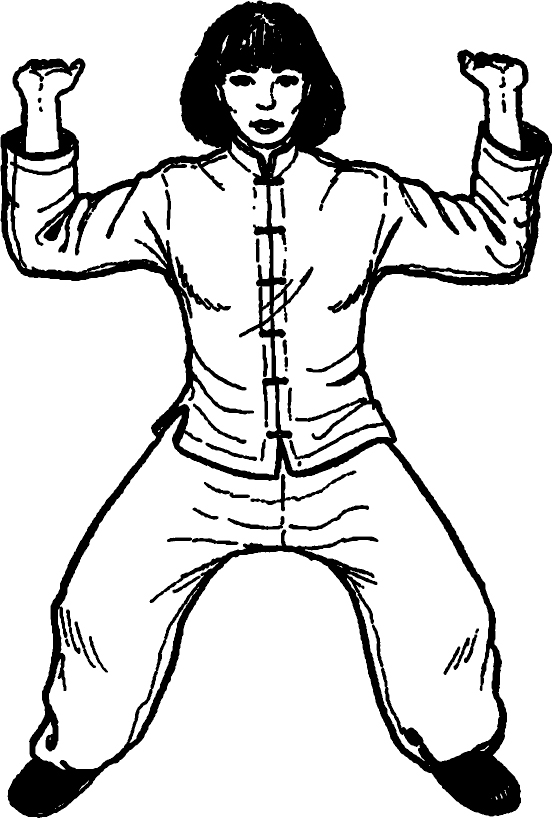

Take a wide and deep “horse-riding” stance. If you are strong and flexible, try standing with the thighs parallel to the ground. Do not stand so low that the knees are strained or collapse inward.

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Begin with the hands in fists, rolled inward at chest height, so the back of the hands are facing each other (fig. 23). As you inhale, pull the right fist back toward the right shoulder, with the elbow extended out, forearm parallel to the ground. At the same time, the left hand opens widely as the arm extends straight to the left side, the whole arm parallel to the ground. The left palm is facing outward. To make this exercise more effective, bend the last three fingers of the left hand slightly toward the palm, so that only the index finger and thumb are extended (fig. 24 is a mirror image). Exhale, forming both hands in fists and bringing them back to the starting position in front of the breastbone. Repeat to the other side.

As you open to each side, the head turns and the eyes look toward the extended arm. Whenever the arms return to the center, the head and eyes are facing straight ahead.

Notice how the chest opens as the arms stretch away from each other and how the chest closes when the fists return to the breastbone. This exercise stimulates and strengthens the lungs.

Figure 23

Figure 24

3. Raise Each Arm to Regulate the Spleen

Stand with the feet parallel, shoulder-width apart. Position your left arm overhead, with the back of the hand resting on the crown. The right hand is resting against the side of the right rib cage, with the palm facing down. Push the two hands away from each other, one pushing toward the sky, the other pushing toward the earth (fig. 25 is a mirror image).

Next, with the arms extended, switch them, circling them at the sides of the body, until the back of the right hand is resting on the crown, the left hand facing down and attached to the left side ribs. Again push the hands away, toward earth and sky. Keep repeating from side to side.

It is generally easiest to inhale as the arms stretch away. However, some individuals prefer to coordinate the exhalation with the arm stretch. Both are possible and beneficial. The head and eyes remain facing forward throughout the exercise. There is no need to look up or down toward either hand.

Figure 25

Figure 26

As with each of the Eight Brocades, this exercise has an external and an internal aspect. Externally, it stretches the arms and opens and closes the ribs. Internally it compresses and releases the stomach and spleen, gently massaging them and improving their functioning.

4. Looking Behind to Cure Fatigue and Distress

With the arms resting naturally at the sides of the body, palms lifted slightly and facing downward, slowly turn the head from side to side (fig. 26). Don’t strain or force the head to turn more than feels comfortable. Do not’ lift or drop the chin as you turn the head. The eyes can either look in the direction the head is facing, or they can look slightly over the shoulder. That is, if you are turning to the left, you can allow the eyes to look farther to the left and perhaps slightly behind the body. The breath can coordinate however feels natural.

This Brocade is great for getting rid of kinks in the neck muscles. It loosens and strengthens the neck, improves posture and spinal alignment, stimulates cerebral blood circulation, and improves vision.

5. Bending Over, Wagging the Tail to Calm Heart-Fire

We can see from the name of this technique how imaginative the Chinese language can be. The practice is even better than the name.

Figure 27

Figure 28

There are two ways to practice this Brocade. From a wide, deep horse-riding stance, rest the hands on the thighs, with the thumbs pointing backward. Then either:

a) Swing the upper body slowly and smoothly like a pendulum. Keeping the feet planted, turn from the waist toward one thigh. Bend down toward that thigh, exhaling (fig. 27). Swing slowly toward the other thigh, with the body still bent over. Then, as you rise up over that thigh, gradually straightening the back, inhale (fig. 28). Continue inhaling as you face the center, returning to your starting position. Then repeat, beginning on the other side. Turn toward the other side; exhaling, bend down and swing the body toward the other leg. Inhaling, rise up over that leg and face center.

Or:

b) From the same stance, turn slightly from the waist, exhale as you bend down over one thigh, turn in the bent-over posture only to the center (not to the other thigh, as in option a above). Inhaling, rise up in the center (fig. 29). Then, exhaling, turn to the other side. Still exhaling, bend down on that side, turn the body to the center, and inhale, rising up and straightening. Some practitioners prefer this variation and claim it is more effective.

Figure 29

This exercise banishes excess “fire” caused by worry, stress, emotional disturbances, and overwork. It helps restore balance to the heart and nervous system.

6. Reaching Down to Dissipate Disease

Stand naturally, with the palms resting on your buttocks. As you bend down, exhale and let the hands lightly slide down the backs of the legs, down to the calves, ankles, or as far as you can bend comfortably (fig. 30). The spine is soft and flexible so each vertebra can relax into the bent posture. Then begin to inhale, allowing the palms to move up along the backs of the legs as you resume the straight stance. Continuing to inhale, the hands resting on buttocks, rise up on your toes (fig. 31). For just a moment hold the breath, imagining the body filled with healing qi. Then rest the feet flat on the ground and exhale again toward the toes, palms moving along the backs of the thighs, knees, calves….Repeat several times.

This exercise helps to draw healing qi into the entire upper body. It also stretches the back, stimulates the kidneys, and massages tight hamstrings and calves.

7. Punching with Angry Gaze to Increase Qi and Strength

According to Chinese medicine the eyes and the emotion of anger stimulate the liver, the muscles, and the flow of qi. Staring with an angry gaze may have been beneficial for ancient Chinese recluses, who probably had low levels of emotional frustration. However, the stress of modern living causes many people to repress or impulsively express anger. Therefore, it may not be healthy for students to cultivate an “angry gaze.” Instead of increasing strength, an angry gaze is more likely to make us tense. So let’s think of “angry gaze” as “intense” or “focused” gaze. Having an intense gaze while punching stimulates the liver and helps it to purify toxins and spread healing qi more efficiently.

Figure 30

Figure 31

Stand with the feet about three feet apart, knees slightly bent. Your stance is slightly wider and deeper than usual, but it is not the strenuous horse stance of Brocade two or five. The eyes are gazing intensely, as though you are a hunter looking for the deer that will feed your family. Both hands are in fists, palms up, under the shoulders. The elbows are pulled back, behind the body. Punch slowly (no jerky or snapping motion) forward with one fist, the hand rotating as the arm extends. By the time you have finished the punch, the palm has rotated downward. Stop the punch while there is still a little bit of bend in the elbow. Do not lock the joint. Now, as the extended fist draws back, palm up under the shoulder, the other fist rotates and extends out. Keep rotating in this way, one fist out, the other back. Punching fist: palm down; fist under shoulder: palm up (fig. 32). Let the breath coordinate with the movements however it wishes. Do not force it.

Figure 32

Figure 33

Figure 34

8. Toe Touching to Strengthen the Kidneys and Waist

Stand in a natural shoulder-width stance. As you exhale, slowly bend toward your toes, allowing each vertebra to participate in the bend. Do the movement slowly enough that you can sensitively relax and release areas in your spine that seem to be adhering together or preventing a full, relaxed bend. If you can reach your toes without straining, grasp them and pull your upper body even closer to your legs (fig. 33). DO NOT ATTEMPT THIS IF YOU HAVE A SPINAL INJURY OR CONDITION FOR WHICH BENDING IS INADVISABLE. Once your body has bent as far as is comfortable, spend a few moments breathing naturally. Notice how the front of the body is compressed, the back of the body open. Let yourself breathe with the kidneys. Feel the lower back expanding and releasing as you inhale and exhale.

Now, after your next exhalation, slowly return to a standing position, inhaling on the way up. Let the vertebrae build, one on top of the other. Stand up slowly, sensitively, with awareness. Continuing to inhale, bend gently back into a bowed-back posture (fig. 34). Now, as you briefly hold this posture, return to natural breathing. Feel how now the back is compressed, but the front of the body is open. The lungs easily expand and contract with the breath. Let it happen! Now take an inhalation, and as you exhale, return to a straight posture and continue exhaling down toward your toes. Repeat the technique several times.

This Brocade looks like ordinary toe touching, but it is really quite different, since its intent is to use the external movement to strengthen inner health. In addition to stretching the spine, it works the kidneys, adrenals, and lungs.

BONE MARROW CLEANSING

The Bone Marrow Cleansing (Xi Sui Jing) includes healing postures, gentle movements, and concentration techniques to cleanse the marrow of toxins.2 It is attributed to the fifth-century Buddhist sage Bodhidharma, and is closely associated with the Buddhist monastery he established, the Shao-lin Temple on Mount Song. Bodhidharma is also credited with two other related qigong styles called the Muscle/Tendon Transformation Classic (Yi Jin Jing) and Eighteen Luohan qigong (Shi Ba Luohan Gong). Historical research suggests that these systems probably date only to the sixteenth century3 and may have been attributed to Bodhidharma in order to give them a more authentic-sounding lineage and to confuse several generations of scholars. Many popular English-language works on qigong maintain the Bodhidharma association. The authors work on the misguided assumption that “if my master said so, it must be true.”

The style of Bone Marrow Cleansing I teach affects more than the bones. It strengthens the immune system, increases the strength and density of the bones themselves, stores qi in the dan tian, and stimulates the flow of qi through the skin and various acupuncture points. Here are the four basic movements.4

1. The Meditating Buddha

Stand in a natural qigong posture with the hands in front of the dan tian. Line up the palms, so that the center of the hands are about twelve inches apart, as though holding an energy ball (fig. 35). Slowly raise the ball up to the level of the chest. Then bend the elbows and move the palms toward each other, until the hands are together in a prayerlike gesture, with the thumbs resting on the breastbone (fig. 36). While maintaining the posture, focus inward on dan tian breathing. Let the mind become silent and calm. Keep this stance for a comfortable period of time, generally about two or three minutes. Then let the hands separate and sink down to the sides. Relax.

Figure 35

Figure 36

Figure 37

2. The Cosmic Being

Slowly raise the arms up laterally, from the sides of the body, with the elbows slightly bent and the palms facing forward. When the arms reach shoulder height, turn the palms outward, facing away from the body, the fingers pointing toward the sky (fig. 37). Holding this posture, imagine that your body is filling the universe: your head touches the heavens, your feet reach to the center of the earth. Your right arm is extended infinitely to the right, your left arm infinitely to the left. You are the cosmic, primal being. Instead of the universe being inside your body (“Meditating Buddha”), here your body has expanded into the universe. Additionally, imagine that the pores of your skin are open. There is lightness, an openness, a porosity to the entire body. Universal healing qi can flow easily through you. Forget about your breath, just let it go as it wishes.

Maintain this focus for about two or three minutes, then bring your mind to the dan tian. Feel your breath moving within, let your spirit return to body-awareness. Then float the arms down to the sides and relax.

3. Wash the Marrow with One Hand

Your left hand slowly floats up behind the body, until the center of the back of the hand is resting comfortably on the lower back, opposite the navel. You have lined up your rear lao gong acupoint on the hand with the ming men (gate of life) on the back (fig. 38a). This improves the functioning of the adrenals and kidneys. As your left hand moves into place, your right hand is rising up from the right side of the body until the palm is about six inches over the crown of the head, facing downward (fig. 38b). Feel the connection between the center of the right palm (the lao gong point) with the point on the apex of the head (the bai hui point). It is as if you are feeling your own energy field, the qi emanating from the crown. This focus helps to balance all yang and yin energy in the body. The bai hui acupuncture point is the point where the yang energy of the back meets the yin energy of the front of the body. This is why the crown point is known as bai hui, literally “hundred meetings.” It is where multiple forms of energy converge.

Figure 38a

Figure 38b

Hold this stance for only a moment, just long enough to feel a pleasant stimulus at the lower back and crown. Then slowly lower the upper hand down the front of the body. As your right hand floats down, imagine that pure healing qi is flowing through the bone marrow. If an image helps you to focus, you can visualize the qi as a healing steam or white light. Qi moves through the bones of the skull and face, down through the vertebrae in the neck; it flows through the collarbones, shoulder blades, ribs, down the spinal column. Your hand is still floating down, ever so slowly. Qi washes through the marrow of the hips, the thighbones, knees, lower legs, feet. As your hand relaxes at the side, the hand at the lower back releases and also floats down. Now see the impure, noxious qi washing out of the feet, sending it at least three feet under the ground. I like to imagine that this unneeded qi is becoming compost or transforming into light. (I believe that impure qi can create psychic, energetic pollution unless we dispose of it properly.)

Now you are ready to switch to the other side. Your right hand slowly rests on the lower back, center of the hand on the spine, opposite the navel. The left arm rises up until the palm faces the crown: lao gong energetically connected with bai hui. Float the left hand down the front as you wash the marrow. Send the impure qi out the feet. Relax both hands at the sides for a moment before switching sides again.

Keep washing the marrow alternately with one hand, then the other, anywhere from three to five times with each hand. There is no need to coordinate the breath with any particular part of the exercise. Breathe naturally. Relax and center yourself for a moment before moving on to the last stage.

4. Wash the Marrow with Both Hands

Raise both hands up the front midline of the body, palms facing up (fig. 39). As the hands reach the breastbone, turn the palms away and push them overhead. The arms are stretched overhead, palms facing the sky (fig. 40). Hold this stance for about ten seconds, imagining that you are like a tree, with deep roots and tall branches, connecting sky and earth. Then turn the palms to face the crown and lower them only slightly, until they are about six inches over the crown. The hands are not touching each other. The fingers of the right and left are separated by a few inches. While holding this position for a moment, feel the energy of your crown, your “aura.” As in “Wash the Marrow with One Hand,” you are connecting the lao gong points, this time of both hands, with the bai hui point. Then float both arms down the front of the body, imagining the pure, healing qi washing through the bone marrow, exactly as in “Wash the Marrow with One Hand.” As the hands reach the sides, the impure qi is pushed out of the feet, under the earth. Relax. “Wash the Marrow with Both Hands” is done only once, closing the set.

Figure 39

Figure 40

THE FIVE ANIMAL FROLICS

The Five Animal Frolics (Wu Qin Xi) are graceful, dancelike exercises modeled after the Crane, Bear, Monkey, Deer, and Tiger. They are a complete qigong system, developing strength, grace, flexibility, balance, and an abundance of healing qi. The Five Animals are medical qigong because they circulate the qi and improve health. They are also martial qigong because they encouraged the development of various Animal martial arts: Crane Style, Tiger Style, etc. And the Frolics are spiritual qigong because they teach harmony with the animals and all of nature.

The Five Animal Frolics is the most ancient qigong system still practiced today. It is also one of the oldest continuously practiced healing exercise systems in the world. The Frolics were created by Hua Tuo (A.D. 110-207), often called “the Father of Chinese Medicine.” The theories of diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis attributed to him are still considered the foundation of traditional Chinese medicine. Hua Tuo’s Classic of the Central Viscera5 was selected by the Chinese Ministry of Health and Hygiene as one of the eleven most important premodern works on Chinese medicine, out of a library of more than ten thousand. According to Daoist legend, Hua Tuo received this text as well as instruction in the Five Animals from two recluses living in a cave on Mount Gong Yi.

Hua Tuo’s two disciples, Wu Pu and Fan A, following their master’s medical advice, lived to age ninety and past one hundred, respectively. Hua Tuo once told Wu Pu, “The body should be exercised, but not to excess. Exercise improves digestion and keeps the meridians clear of obstructions. In this way, the body will remain free of illness. A door hinge does not rust if it is frequently used. Therefore the ancient sages practiced dao-yin….I have created a dao-yin method called the Five Animal Frolics. It can eliminate sickness and strengthen the root.”6

The modern resurgence of interest in the practice of the Five Animals is largely due to the influence of a famous Beijing actress, Madame Guo Lin (1906-1984). After an eight-year battle with uterine cancer, doctors pronounced her inoperable and gave her six months to live. Madame Guo began to practice the Five Animal Frolics two hours a day at dawn. Six months later, she was in remission.7 In the 1970s, almost thirty years after her fatal prognosis, Madame Guo became a national hero in her campaign to introduce qigong into hospitals and clinics throughout China. She wrote the first book specifically devoted to qigong for cancer.

Another very strong influence on the spread of the Five Animal Frolics is qigong master and doctor of Chinese medicine Hu Yao-zhen. Hu taught qigong to many of the best present-day instructors, including the famed Taiji Quan Master, Feng Zhi-qiang. The Five Animal Frolics Hu describes in his book, Wu Qin Xi,8 is almost identical to the style I learned from Dan Farber, a student of retired Hong Kong master Qin Xu. Dr. Hu’s book is probably the best work on the subject in the Chinese language. One of his students, Jiao Guorui, learned the Five Animals from Dr. Hu in the 1950s and includes significant portions of Wu Qin Xi in his English-language work Qigong Essentials for Health Promotion.9 Excellent translations of the principles of the Five Animal Frolics (again from Hu Yao-zhen) can be found in the writings of a Western qigong master, Paul Gallagher.10

I will describe the practice of the two foundation exercises of the Five Animal Frolics: the Crane and Bear. The Crane is the symbol of meditative stillness and longevity. In Chinese mythology, the crane is the companion of Shou-lao, the God of Longevity. Daoists say that enlightened sages ride to heaven on the back of a crane. The Bear is a symbol of strength, power, and healing wisdom. In ancient China, the shaman-healers wore bear masks and may have imitated the stepping of the bear in ritual dance.

The Crane and Bear are the yang and yin of the Five Animals. The Crane is light, relaxed, excellent for the heart and to keep the body cool in summer. The Bear is heavy, strong, stimulates the kidneys, and warms the body in winter. Practice both of them during the same workout. This will keep yang and yin, fire and water, in balance. The Crane and Bear can be practiced safely and with excellent health benefits even if one does not know the other three.

When you practice the animals, do not imitate the animals, become them! Ideally, one could observe the animals (from a safe distance) in their natural environment and practice in that environment. I love to practice the Crane by the edge of a lake and the Bear in the forest. Be careful, however; if there is a bear nearby she might think you are a relative! At the very least, visit the zoo and see how the animals actually move and behave. A monk asked a Zenmaster if a dog has the Buddha-nature. A qigong practitioner asks, “Does a Buddha have the dog-nature, the bear-nature, the crane-nature?” An enlightened being feels connected with all “creature teachers.”11 There is an ancient biblical midrash (commentary) that asks, Why is the plural used in “Let us make man in our own image”? The midrash answers its own question, “The ‘us’ refers to all of the animals, which were created first.” The spirits of the animals helped to create the first human.

The Crane

All Crane Frolic techniques begin from the Crane Stance. Maintaining the principles of qigong posture, stand with the heels together, a forty-five-degree angle between the feet. The knees are only slightly bent. The body is tall and open, like a great pine tree. The eyes gaze long, into the distance. Throughout the Crane the body should also have a lightness and porosity like a cloud. You should feel finely and delicately balanced. A Crane can stand for hours, balanced on one toothpick leg, completely still, as though asleep, yet it is perfectly alert. When a fish swims by, whoosh! it is caught. In the Chinese language the word for contemplation, guan, was originally a picture of a crane.

Figure 41a

Figure 41b

Figure 42

Figure 43

Crane movements are practiced at a relaxed, slow, and even pace, as though swimming in the air. The Crane is like a meditative dance with six distinct techniques. Repeat each technique nine times, then pause for a moment and move on to the next.

1. Standing Crane: Hold your hands palms up just in front of the dan tian with your fingertips almost touching. As you inhale, raise the lower arms and hands up to the lower tip of the breastbone (fig. 41a). Be careful to keep the shoulders relaxed; don’t raise the shoulders or chest. As you exhale, keeping the palms facing upward, lower the hands down to the dan tian. Continue, inhaling, hands raised to chest. Exhale, and drop hands to lower abdomen (fig. 41b).

2. Crane’s Beak: Hold the arms out at the sides at shoulder height, palms facing down (fig. 42). There is a straight line along the shoulder, upper arm, forearm, wrist, and hand. The elbows are slightly bent. As you inhale, raise the arms about six inches higher. At the same time, let the fingertips of each hand touch together, forming a point, the crane’s beak (fig. 43). As you exhale, relax open the crane’s beak and float the arms down to the starting position, arms and hands outstretched at shoulder height.

3. Crane Flaps Wings: Begin the same as Crane’s Beak: arms to the sides at shoulder height, palms down. As you exhale, lower the arms until the hands are the height of the waist (fig. 44). As you inhale, raise the arms back to shoulder height. The hands stay open the whole time, swimming gracefully through the air. After the last repetition go straight into Crane Squatting.

Figure 44

4. Crane Squatting: We continue from the end of Crane Flaps Wings. The hands are resting at the level of the waist. As you inhale, slowly squat. Let the heels lift from the ground; the knees bend and bow out to the sides. You are going into as deep a squat as comfortable. At the same time, lift the arms and turn the palms up. The arms rise until they are as high as the shoulders (fig. 45).

Figure 45

Figure 46

Figure 47

Now, as you exhale, slowly stand up. At the same time, the hands turn palms down and float down to waist height. Repeat.

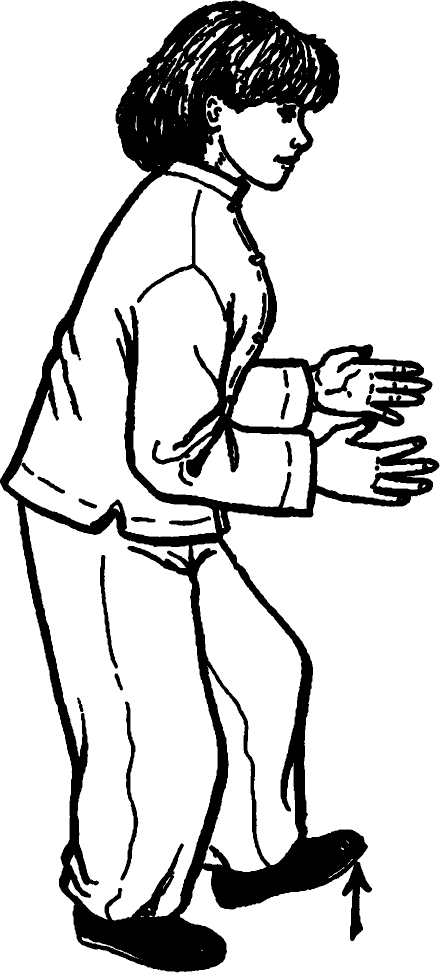

5. One-Legged Crane: Begin with the hands palms down at waist level. While exhaling, squat and reach down with the arms, as though embracing the knees (fig. 46). As you inhale, stand back up, shift the weight to one leg, and cross the arms in front of the chest, palms facing the body. Still inhaling, raise one knee up in the air until the thigh is parallel to the ground. At the same time circle the arms overhead and out to the sides, until they are extended laterally at shoulder height. Hold this balanced position for a few seconds (fig. 47). Then again slowly exhale, go into a squat, and embrace the knees. Inhale, going back to the erect posture, hands crossed. One leg lifting, the arms continuing overhead and out to the sides of the body. Hold for a few seconds and repeat.

Figure 48

Figure 49

6. Crane Spreads Wings: Begin in the standing posture, heels touching, arms at the sides. As you inhale, draw both arms slightly back behind the body. One foot takes a step out and touches the ground lightly on the toe. All of the weight is on the rear foot (fig. 48). Now, with the exhalation, bring the extended foot back, balance the weight evenly on both feet, and bring the arms to the front of the body, with the back of the hands facing each other (fig. 49). Then, again inhale, reach out with the other leg, touching the toe, arms behind the body (not too far, don’t strain the back!). Exhale, heels together, weight even, arms rolling in toward the front of the body, back of the hands facing. Keep repeating side to side.

Make sure that each toe-step is light and delicate, as though you are not bending a blade of grass.

Now that you have finished the basic Crane Frolic, stand in quiet meditation for a moment, then take several steps, walking about for a minute or two. What has changed? Most students feel as if they are as light as a feather and that their arms and legs have grown a few inches longer.

The benefits of the Crane include relaxation, balance, loosening and opening the joints, strengthening the heart and lungs, cooling the body, shrinking inflammation, and relieving congestion.

The Bear

The Crane is light and ethereal. The Bear is heavy and rooted. Will you forgive a playful stereotype? In the United States I like to teach the Crane in New York City, to lift students out of the rat race and paranoia of crowded streets and busy subways. I emphasize the Bear in California: a good antidote to excessive sunshine and alfalfa sprouts.

The essence of the Bear Frolic is to feel sunken, stable, heavy, ponderous. According to Hu Yao-zhen, your movements should also be easy and fluid, “as though you have no bones.” Lightness, agility, and alertness are concealed within. This is consistent with the nature of the bear, who can amble about slowly or charge with surprising speed.

The Bear Stance, used throughout the exercises below, is a wide, low horse stance, with the feet turned forty-five degrees out. Advanced practitioners can stand with the thighs parallel to the ground. Pregnant or menstruating women should not attempt the deep posture. Rather, find a stance that is comfortable and causes no strain. The eyes have a quiet, relaxed gaze. Qi is sunk in the dan tian. As in the Crane, the movements flow one into the other with only a slight pause between techniques. Each technique is repeated nine times to each side.

1. Bear Turns: While in the Bear Stance, hold the arms at the sides of the body, elbows bent to ninety degrees, hands facing upward at the height of the ears (fig. 50). Slowly turn from your waist to the left, exhaling (fig. 51). Be careful to turn only from the waist, do not shift the weight or turn the hips or thighs. The stance is fixed and immobile. Turn as far as you can comfortably, without strain. Then, as you inhale, return to center. Now exhale and slowly turn to the other side. Inhale, face center. Keep turning side to side, coordinating with the breath. The hips are fixed, the waist is turning. It is this differentiation of waist from hip that massages the internal organs and benefits the kidneys. After the last repetition, go straight into Bear Pushes Behind.

Figure 50

Figure 51

Figure 52

Figure 53

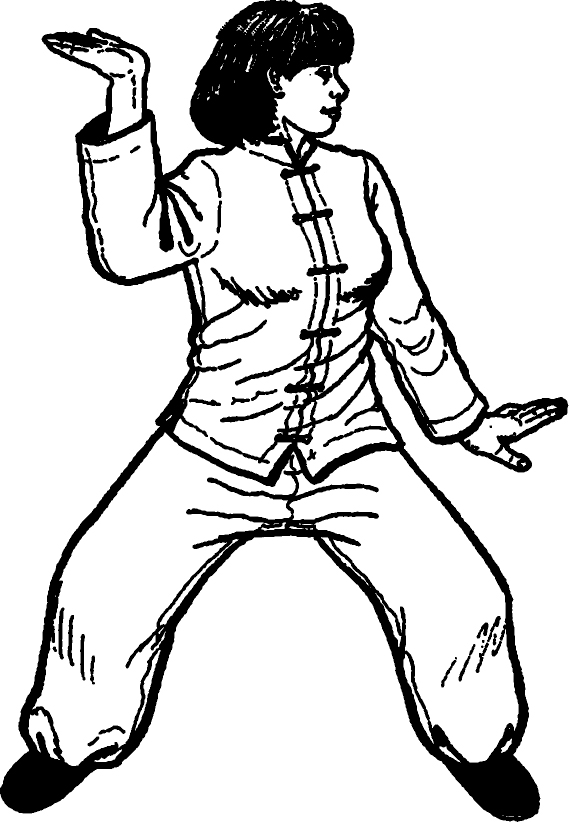

2. Bear Pushes Behind: This time, as you exhale, turning to the left, push the left hand out behind you, keeping it at shoulder height, palm facing away, fingers toward the sky (fig. 52). As you inhale, face the front and bring the left hand back to the original bear posture, elbow bent to ninety degrees, palm facing up. Then turn to the right, exhaling and pushing the right palm out and away from the shoulder, fingertips pointed up. Inhale back to center. Repeat side to side.

3. Bear Pushes Down: Continue the basic movement of Bear Turns. This time, as you turn to one side, exhaling, push one hand down by the hip (fig. 53). For instance, exhaling, turning to the left, push the left hand down behind you, until the palm is facing down near the left hip. Inhale, facing center and bringing the hand back to the starting posture: both hands palm up at ear height, as though holding a wooden plank overhead. Then exhale, turning to the other side, the other hand pushing down by the hip. Inhale, back to center.

Figure 54

Figure 55

4. Bear Offering: Bring the hands to rest on the lower chest, just below the breastbone, palms facing up (fig. 54). As you exhale and turn the waist to the left, extend the left hand, palm up, away from and at the height of the shoulder. The right hand extends slightly out to the left and rests palm up on the middle of the left forearm (fig. 55). Inhale, face center, both hands returning to the chest, palms facing the sky. Then turn to the right, the right hand reaching out, palm up, until it is extended laterally, at shoulder height. The left hand is palm up and resting on the middle of the right forearm. Inhale, back to center.

5. Bear Push: Begin as above, both palms facing upward under the chest. This time, as you turn and exhale, push both hands out to the side. The palms are facing away. The hands push on a plane, as though both palms are resting on a wall at your side (fig. 56). Inhale, face center, hands returning to the chest. Exhale, push to the other side.

As you finish this set, resume a comfortable, shoulder-width stance and let the hands rest at the sides. Stand in quiet meditation, then saunter about for a minute. Notice how different you feel now compared with how you felt after the Crane. What effect has the Bear had on your standing and breathing, on the weight of your body, on different parts of the body? It is common to feel as though the body is so grounded that you have become a moving mountain. You may also notice that the lower back and kidney region are pleasantly warm.

Figure 56

The Bear should be practiced all year. However, its benefits will be most appreciated in winter. The Bear warms the body, improves kidney and adrenal function, deepens the breath, and greatly strengthens the legs and waist.

Readers can find further information about the Animal Frolics by consulting materials listed in the Qigong Resources. The Five Animal Frolics continues with complex Crane and Bear walking exercises and frolics based on the monkey, deer, and tiger. The Monkey has a light, agile quality and helps to loosen the joints. The Deer stretches and twists the spine and hips, creating flexibility and grace. The Tiger is fierce and powerful, strengthening the muscles and tendons.

TAIJI RULER

The Taiji Ruler (no relationship with Taiji Quan) is a sacred and secret qigong first made public in 1954 by Master Zhao Zhong-dao. It is called the Ruler (Chi, sometimes spelled Chih) because during the basic exercise the hands are held about a foot apart.12 The Taiji Ruler system consists of gentle rocking and swaying movements that build qi in the feet, the dan tian, and the hands. It can be used for self-healing or as a preparation for any form of massage therapy or therapeutic touch. Your hands will feel warm, vibrating, full of healing power after a few minutes’ practice. In the United States, several bizarre variations of the Ruler have become popular, many with little relationship to Zhao’s original techniques. The method I present has been synthesized from direct students of Zhao, several second- or third-generation students, and then corroborated by comparison with Zhao’s original Chinese text.

The Ruler has a fascinating and venerable history. The Taiji Ruler is one of several forms of qigong attributed to the tenth-century Daoist recluse Chen Xi-yi.13 Chen lived on Mount Hua, the Daoist sacred mountain in Shenxi Province. The Jade Spring Temple at the foot of the mountain was designed by Chen and contains a statue of him. The monks still recount a legend that after Chen died, his bones glowed with red light. A visitor once stole the shinbone. This so infuriated the monks that they moved his remains to a secret location, never again revealed.

For many years Chen was friends with a young visitor named Zhao Kuang-yin. Zhao loved the beauty of the mountains and frequently journeyed to Mount Hua to join Chen in two of his favorite pastimes: playing Chinese chess (wei qi) and practicing qigong. Years later, when Zhao rose to power as the first emperor of the Song Dynasty, he taught Master Chen’s qigong methods to his children. Chen’s Taiji Ruler method was maintained within the imperial family, passed down from generation to generation as a precious heirloom and secret to good health. Toward the middle of the nineteenth century, the art was transmitted to a direct descendant, Zhao Zhong-dao (1844-1962). Just before Zhao’s grandmother died at age 108, she told her twenty-two-year-old grandson, “Although the Taiji Ruler cannot make you an immortal, it can certainly rid you of disease and increase your life span. Do not overlook it.”

Zhao kept up the family practice, and in 1954 he founded in Beijing “The Gentle Art of Taiji Ruler Health Society,” the first school to publicly teach the Taiji Ruler. The Society was like a university teaching hospital. Scientists and qigong practitioners from all over China came to learn the art. Patients with debilitating and chronic diseases arrived for treatment. The Society was very successful treating digestive and nervous system disorders, insomnia, high blood pressure, and numerous other problems that had failed to respond to medical treatment.

According to Master Zhao’s biography, when Zhao passed on at age 118, “He did not have the appearance of a flickering lamp. On the contrary, he had a child’s complexion and silvery hair. His face exuded a healthy reddish glow and he could chat for hours. One glance and you knew this was an exceptional human being….His hearing and vision were sharp. He had strong teeth, unwrinkled skin, and he slept and ate like a young man.”14

The Ruler is a complex and complete system of qi development that includes numerous solo exercises, exercises with training equipment, and two-person routines. Almost all teachers of the Ruler begin with the same foundation exercises.

The Basic Rock

Stand with your feet about 10.5 inches apart. The left foot is pointing straight ahead. The right foot is at a forty-five-degree angle. The left foot is about five or six inches in front of the right, so that the toes of the right are on a straight line with the left instep (fig. 57). Bend both knees until, as you look down, the front knee is directly over the toes, hiding them from view. Now lean slightly forward, letting the hands slide down the front of the thighs until your fingertips are almost touching the top of the kneecap. The body is in a stooped-over posture. Do not slouch the shoulders or bow the upper back. Rather, bend from the waist. This allows you to maintain a straight line from tailbone to crown. This is the Taiji Ruler Stance (fig. 58) and is the foundation of The Basic Rock and The Basic Ruler, which follow.

Figure 57

Figure 58

Keeping the left hand on the lower thigh, draw the heel of the right hand into the right kua, the crease between the thigh and hip (the inguinal area). The fingers of both hands are facing down.

While keeping this position, begin the Basic Rock. Rock the body ever so slightly to the front. As you do so, raise the rear heel an inch or two in the air. Then rock slightly back, lifting the front toe slightly off the ground. Keep rocking, back and forth, like a rocking chair. Find a way to rock back and forth with almost no shifting of weight, as if your body can move only as a whole, in one piece. One foot is always flat on the ground. Front toe up, rear foot flat. Rear heel up, front foot flat. Do this for a few minutes. Then switch sides.

Right foot in front, pointing straight. Left foot forty-five degrees. Feet separated by about 10.5 inches. Right heel in line with the left instep. Bend the knees until your knees cover the toes. Then bend the back until the fingertips almost reach the kneecaps. (Of course, in the bent-over posture you can see your feet.) The back is straight. Keep your right hand above the knee but rest the left hand on the left kua. Now begin rocking. Rear heel up, front foot flat. Front toe up, rear foot flat. Practice for a few minutes. Then go directly to the next exercise. They should be performed in sequence.

The Basic Ruler

Now switch sides again. Go into the Ruler Stance. This time the hands are held a few inches in front of the navel, about ten inches apart, as though holding an energy ball. The palms and fingers are gently spread open. The centers of the palms are lined up. Begin the Basic Rock. As you rock to the front, rear heel lifting, dip the hands slightly down, about three inches below the navel. As you rock back, front toe lifting, the hands lift up and circle inward. You are carrying the energy ball in a circle, down, away, up, and back, coordinated with your rocking (figs. 59, 60). The navel is the center of your circle. As you rock back and forth, the ball is circled about three inches above the navel and three inches below it. Do thirty-six repetitions.

Then try it on the other side. Circle the hands in exactly the same way. Rock to the front, the ball drops. As you rock back, the momentum of the backward movement causes the ball to effortlessly lift up and draw back toward the body. Repeat thirty-six times.

Figure 59

Figure 60

Make sure that the breath is relaxed and natural as you practice the Ruler. Don’t force or stop the breath. Just let it go. To close the exercise, gently stop rocking. Let your body settle into stillness. Then slowly straighten the legs until the knees are only slightly bent. Then very gently straighten the back. Relax all the way down to your feet.

In just five minutes, the Ruler gives a powerful workout. The Ruler exercise stimulates the Bubbling Well acupuncture points in the feet, the points that feed the kidneys and bones with earth-qi. It also puts a stimulating pressure on the ming men point on the lower back, opposite the navel, increasing overall vitality. The bent-over posture feels almost fetal and compresses breath in the dan tian, increasing its store of qi. Provided you are not bending excessively and the back is straight, long, and open, you should still be able to breathe easily. The legs, waist, and back become stronger.

However, if you have a lower back problem, such as arthritis or a damaged disk, you may need to practice this exercise without inclining the back. If you are overweight, have high blood pressure, are menstruating or pregnant, practice from a plumb erect posture with the knees only slightly bent to avoid putting pressure on the dan tian. If you have a disability that makes it painful or impossible to stand, then sit in a chair and practice the hand-circling movements of the Basic Ruler without the toe-heel rocking. This Seated Ruler has similar, though less dramatic, energetic effects on the body’s qi. Naturally, it does not have the same physical effects of strengthening the back and legs.

Remember, if you have any doubts about the advisability of this or any other qigong, check with a health professional. Even if you can’t practice, maybe you can inspire your physician to try it. (If your health-care provider already knows everything there is to know about health, please suggest that he affix himself to the altar at Church.)

ARM SWINGING: THREE MINUTES TO BETTER HEALTH

This method is probably a recent innovation, yet it is so simple, gentle, effective, and popular that I include it here among the “classics.” Arm Swinging gives a quick charge-up and is an excellent way to improve blood and qi circulation and to begin any kind of exercise routine. If you go early in the morning to a park near any Chinatown in North America, you are likely to see seniors standing in place and swinging their arms back and forth without stopping, sometimes for as long as five minutes. Arm Swinging is the most popular qigong for the elderly.

Stand with the feet parallel, shoulder-width apart, your whole body in a relaxed qigong posture. The arms are relaxed at the sides. Breathe naturally; don’t worry about or focus too much on the breath. Throughout this qigong, the toes gently curl inward as though gripping the ground. At the same time, imagine that the heels are pressing into the ground. You will feel as though the arch of the foot, the Bubbling Well point, is lifting up, creating a kind of suction that draws qi into the body.

Now, gently swing the arms front and back, like a pendulum. Not too big a movement, perhaps a foot or two front and back, less if you have bursitis or painful shoulders. Find a comfortable, fluid rhythm. You will find that once you start, the movement seems to continue of itself, effortlessly. Continue for three to five minutes. Then slowly and gradually make the swinging movements smaller and smaller, until they settle into stillness, like a bouncing rubber ball settling into the ground. Release any gripping in the toes or heels. Stand for a minute enjoying the feeling of greater aliveness.

HONORABLE MENTION: A THOUSAND CHANGES, TEN THOUSAND TRANSFORMATIONS

All of the styles of active qigong described in this chapter are technically classified as soft qigong (rou gong) or inner qigong (nei gong), because they use minimal strength and emphasize the gentle and gradual cultivation of health and awareness. Other excellent styles of soft qigong that are becoming popular in the West include the Swimming Dragon, Soaring Crane, and Coiling Silk.

In contrast to soft qigong, hard qigong (ying gong, also called external qigong, wai gong) consists of vigorous methods of conditioning and strengthening the body. In China, hard qigong is often practiced by athletes engaged in the martial arts or other contact sports. Qigong does not disparage muscular or aerobic conditioning. It only warns that this not replace the deep internal healing methods.15

All Chinese martial arts emphasize qi development at the higher levels of training. But the inner martial arts (nei jia quan) teach numerous hard and soft qigong training techniques from the beginning. The three most popular inner martial arts are Xing Yi Quan, Bagua Zhang, and Taiji Quan (also spelled T’ai Chi Ch’uan).16 All three include both freestyle, full speed sparring training as well as precisely choreographed solo exercises that can be practiced as qigong.

The inner martial arts are becoming increasingly popular in the United States. Teachers of each of these arts can be found in most major cities. Martial arts tournaments generally include competition categories for each style. Magazine articles describing Xing Yi Quan, Bagua Zhang, or Taiji Quan appear frequently in the martial arts magazines. There are also specialized journals devoted to each of the three arts.

The inner martial arts are far too complex to learn accurately from a book. However, for a more complete appreciation of qigong practice, it is important to at least be familiar with their major characteristics.

Xing Yi Quan

The name Xing Yi Quan means Form (Xing) and Intent (Yi) Fighting, suggesting the integration of body and mind. Although legend traces the art to General Yueh Fei (960-1127), the documented founder is a man named Ji Long-feng, who learned it from a Daoist hermit in the middle of the seventeenth century.

Of the three inner martial arts, Xing Yi Quan is the most martial in appearance. Xing Yi Quan consists of linear strikes, in which the entire body is driven forward like a battering ram. The five basic strikes are based on the Five Elements and have healing side effects. For instance, the metal strike chops like a metal ax and benefits the lungs. The wood strike looks like a shooting arrow and is generated from the liver area. Water drills and spirals into the opponent in an uppercut, with power rising from the lower back and kidneys. Fire shoots explosively from the chest, like a cannonball, and stimulates the heart. Earth, for the spleen, is a side-to-side, lateral strike directed to an opponent’s side ribs. The Xing Yi Quan system also includes twelve animal-like movements: the Dragon, Tiger, Monkey, Horse, Lizard, Chicken, Hawk, Sparrow, Phoenix, Snake, Eagle, and Bear.

Xing Yi books in the Chinese language are filled with sound advice on qigong: the importance of relaxation, sinking qi to the dan tian, natural breathing, postural alignment, etc. Xing Yi qigong also includes standing, breathing, and range-of-motion exercises similar to those found in the qigong classics.17

Bagua Zhang

Bagua Zhang is the most mysterious of the inner martial arts. The movements are circular, coiling, spiraling, like a dragon or snake. The name Bagua Zhang means Eight Direction Palm, and includes elusive, swift changes of posture and direction. It was probably originally practiced as a series of palm strikes, blocks, and evasive maneuvers around eight wooden posts. When applied in combat, the Bagua fighter spirals around the opponent, striking, trapping, locking, or throwing him.

Bagua Zhang is well-known for its unique qigong training technique, known as “walking the circle.” The student walks in a circle while holding various postures. The gait is extremely narrow, as though walking on a circular tightrope. Every aspect of the posture is choreographed with extreme precision: the angle of the feet, the position of the elbows, the amount of twist in the waist. All of these elements help to cultivate strength, flexibility, and qi.

We know little about the origins of Bagua Zhang. The first references to the art occur at the end of the eighteenth century. The founder, Dong Hai-chuan (1798-1897), supposedly studied the art for eleven years from two Daoists in Mount Omei, Sichuan Province. Dong kept the art to himself until commanded to demonstrate before Prince Su, a relative of the Qing Dynasty emperor. When Dong defeated the Prince’s champion boxer, the head of his Royal Guard, Dong became quite well-known at court.

The most entertaining story of Dong concerns his death. When his students attempted to raise his coffin, they couldn’t budge it. It was so heavy that it seemed bolted to the ground. As they tried to lift it again, they heard a voice from inside the casket saying, “As I always told you, none of you has achieved even a tenth of my skill.” With that Dong really died; the casket became light and was carried to the funeral.

Taiji Quan

Among the three inner martial arts Taiji Quan is by far the most popular. The best-known styles of Taiji Quan, called the Yang Family and Wu Family Styles, include relaxed and slow-moving exercises, one posture flowing into the next without break, like a stream. The other, more ancient style, Chen Family, consists of dynamic changing rhythms, with more obvious martial applications. The Chen Family Style includes slow storing of energy (yin) followed by dramatic explosions of power (yang). It has been compared to the ocean, with crashing waves and slowly retreating tides.

Taiji Quan is practiced by millions of Chinese every day and by thousands of Americans. The name Taiji means “Undifferentiated Unity.” Quan means boxing or martial art. Taiji is a philosophical concept referring to the harmonizing of yin and yang. If yin is the shady slope of the mountain and yang the sunny slope, then Taiji is the peak where they meet. In ancient Daoist texts, Taiji can also mean the Polestar. Again, this connotes the balance of yin and yang. The Polestar is the unmoving pivot around which the constellations seem to rotate: stillness within motion, yin balanced by yang. The Taiji Quan exercise cultivates these qualities of balance and harmony.

Taiji Quan is often attributed to a Daoist monk named Zhang San-feng, who supposedly lived almost a thousand years ago. However, Zhang is probably a fabrication of spirit mediums who channeled his biography hundreds of years after his supposed death. The documented history of Taiji Quan actually begins in the sixteenth century with a general named Qi Ji-guang (1528-1587). General Qi (not to be confused with the similar-sounding word “qi” used in qigong) defended the Chinese against seafaring invaders by feigning weakness, enticing the enemy to enter more deeply into Chinese territory. Then his army would massively and decisively counterattack. In General Qi’s Boxing Classic, this strategy became the basis for hand-to-hand combat. He called his art rou shu, the gentle art (jujitsu in Japanese). Yield out of the way of an attack, respect the opponent’s opinion. If he wants to go a certain direction, avoid the blow and help him along! With the enemy off balance, your own attack will be much more effective.

The martial postures described in the Boxing Classic became the basis for Taiji Quan. A contemporary of General Qi, named Chen Wang-ting, incorporated most of these postures into the first Taiji Quan form. Chen considered Taiji Quan primarily a martial art. However, it is also likely that Chen was influenced by Daoist qigong and meditation techniques. We know that Chen enjoyed reading a difficult and secret text on Daoist meditation, the Yellow Court Canon. He may have intended the Taiji Quan exercise to be a kind of meditation in motion: martial art, qigong, and meditation all rolled into one. In recent years the healing aspect of Taiji Quan has become very well-known. Many students are completely unaware of its martial and military origins.

I have often been asked if qigong is form of Taiji Quan. It is just the opposite. Taiji Quan can be considered a form of qigong. The solo exercise follows all of the guidelines for qigong posture and breathing. It shares with Yi Quan Standing Meditation a strong emphasis on developing a particular qigong skill, peng jing, commonly translated “ward-off power.” Peng jing means that any particular part of the body or the body as a whole has a buoyant fullness, capable of rebounding incoming force. The body is filled with qi in the same way that a basketball is filled with air, the force evenly distributed across the rounded surface. When an object hits the ball, it bounces back. Of course, the ball must be firmly rooted, connected into the ground, so that there is a base from which the rebound can occur. In the martial arts, peng jing means that one can discharge an opponent with little expenditure of energy. Peng jing is also healing because it can prevent or lessen injury from any kind of impact.

Taiji Quan is a whole body qigong, encouraging free and unobstructed circulation of qi. According to Taiji Quan instructor Stuart Olson’s work, The Intrinsic Energies of T’ai Chi Ch’uan, “The idea of ‘free circulation’ is to permeate all the bones and flesh, every minute cranny and crevice, with not only ch’i [qi], but blood as well. This is what the Chinese call ‘nourishing life’ (yang sheng).”18