CHAPTER FIFTEEN

External Qi Healing: Chinese Therapeutic Touch

Place yourself in the middle of the stream of power and wisdom which animates all whom it floats, and you are without effort impelled to truth, to right and a perfect contentment.

—RALPH WALDO EMERSON, SPIRITUAL LAWS

THE HEALING PRESENCE

“You know, Ken, I have become too popular! I have so many patients that sometimes I have to schedule them one or two weeks later. But if their problem needs more immediate attention, this seems very unfair. I had to find a solution.”

This is how my old teacher and beloved friend, Dr. Wong, began a conversation as we sat down in our favorite restaurant. It had been several years since my last visit, yet it seemed as though we were resuming a conversation we had begun only the day before. When good friends meet, time is irrelevant. They start up from where they left off. As in the past, many of my “lessons” took place over a meal or informally in his living room.

“Did you find a solution, Dr. Wong?”

“Oh, yes,” he said with a twinkle. “Provided the patients are not suffering from a contagious disease, I ask a group of them to meet me in a café for a cup of tea.”

“Yes…?”

“Then I shake hands with each of them. By the next day, some of them call me back, saying, ‘Dr. Wong, cancel my appointment. I don’t know what you did when we shook hands, but I am feeling all better!’ ”

This was a wonderful lesson, as it reconfirmed an opinion I had long held about the naturalness of healing energy. Every contact with another human being (or with an animal, plant, and perhaps any aspect of nature) has the potential for healing or harm. Our very presence can be a healing help and positive influence on those we care about.1

When I questioned Dr. Wong about methods of training or increasing the power of this presence, he said, “Practice qigong.” If two acupuncturists apply the same technique, the one with qigong training will be more effective. “When I hold the needle,” said Dr. Wong, “the needle is not the needle. My whole body is a needle, an antenna for the universal breath of Heaven and Earth.”

At a high level of training, it is possible to dispense with the needle and simply point one’s fingers at the acupoint to achieve the same effect. Or one can project qi directly into an afflicted area of the body with or without touch. Qi can be projected during any other method of healing body work such as massage, osteopathic adjustments, chiropractic, Rolfing, Therapeutic Touch, or laying on of hands. It can greatly increase the efficacy of any of these techniques. This unique application of qigong for healing others—projecting qi outside of one’s own body and into a patient—is called External Qi Healing (EQH, Wai Qi Zhi Liao in Chinese).

In China, External Qi Healing usually refers to noncontact therapeutic touch, the hand or hands held approximately six inches above the area of treatment. According to Chinese works on the subject, EQH is excellent therapy for the same range of problems treated by acupuncture. It is very effective in “reducing pain, shrinking infections and swellings, killing cancerous cells, combating arthritis, releasing muscular tension, improving skin tone, stopping bleeding, strengthening the immune system, renewing vitality, etc.”2 Compared to acupuncture patients, those treated by External Qi have less frequency of disease recurrence.3

EQH is also the most accessible form of Chinese medicine, the easiest for anyone to learn. Although it may be applied as an adjunct to acupuncture therapy, it can also be practiced by those unfamiliar with Eastern philosophy. It does not require knowledge of meridians, acupoints, or Chinese medical theory. Unlike many qigong instructors, I do not believe that EQH is only for the advanced. I do not accept that one must wait ten years before attempting it. On the contrary, we are emitting qi all the time, with or against our will. We need to learn how to use this innate capacity effectively and wisely.

I was inspired to learn External Qi Healing by an experience I had in the early 1970s. One day after practicing qigong in a park, one of my students, a woman in her twenties, asked me, “Have you ever thought of using your qi to heal someone else?” She explained that she had an ovarian cyst. One ovary had already been removed, and a large cyst was growing on the remaining one. Although I didn’t know if I could help, I was certain that I would do no harm. I asked her to lie down on her back on the grass. I placed both of my palms about six inches above her abdomen and imagined myself practicing Standing Meditation. I was not trying to project healing qi, nor to change or manipulate her energy. I was simply tuning in.

After about fifteen minutes, I finished and asked her how she felt. She said that she felt warmth and tingling throughout her abdomen. This was a positive sign of qi flow and sensitivity but not necessarily an indication of therapeutic effect. A month later, she told me that when she had returned to her physician for a checkup, there was no sign of the cyst! Of course, I have no way of knowing for certain that 1 caused its remission, but I am very happy that now, more than twenty years later, she is a healthy and proud mother.

HISTORY OF EXTERNAL QI HEALING: THE ROOT OF CHINESE MEDICINE

The method of transmitting qi probably goes back to the very roots of Chinese medicine in ancient shamanism. The word for doctor or medicine in Chinese is yi, a word that originally consisted of two pictograms: a quiver of arrows in the top of the character and a dancing shaman (wu in Chinese) on the bottom. The arrows represent spiritual power, qi—either healing qi projected from the healer into the patient or arrows of noxious qi energetically removed by the healer.4

In ancient China, doctors were shamans. Yi Zhou Shu (The History of the Zhou Dynasty) quotes the Duke of Zhou (c. 1020 B.C.) as saying that in the past, “every village had a wu medical office.” These shaman-doctors were probably China’s original herbalists. In Chapter 16 of an equally ancient text, Shan Hai Jing (The Classic of Mountains and Seas), there is a list of ten shamans who lived on a mountain “where a myriad of healing herbs grow.” The names of these shamans suggest that they also practiced acupuncture, using bone, thorn, or stone needles—for example, Wu Geng (Fish-bone Shaman), Wu Di (Thorn Shaman), and Wu Xian (Needle Shaman).5 We see the same association between shamanism and doctors in the Analects of Confucius: “One who lacks perseverance will make neither a shaman nor a doctor.”6 In a stone relief at the Confucian Temple in Qu Fu (Shandong Province), Bian Que, a physician from the fourth or fifth century B.C., is represented as a feathered shaman, a bird-man, one with nature and soaring beyond the fetters of intellect. These shaman-doctors, like shamans the world over, may have occasionally used healing tools such as herbs or acupuncture needles. However, they were also capable of contacting the forces of nature directly and channeling this power to the patient through intent, prayer, and energetic touch.

One of the ministers of the famed Yellow Emperor, Patriarch of Chinese Medicine, was such a shaman. In The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine, a text probably dating from the second century B.C., we read that this minister, Zhu You, preferred to treat illness through exorcistic prayer rather than needles or herbs. Some scholars believe that Zhu You practiced External Qi Healing at the same time that he prayed for patients.7 This is remarkably similar to the synergism of noncontact healing and prayer in Native American and other indigenous healing traditions. The Yellow Emperor’s Classic states that in ancient times most illnesses were treated according to the methods of Zhu You. China’s great etymological dictionary, Shuo Wen Jieh Zi, says that professional “prayer healers” (zhu) were once widespread in China. They may have formed a specialized branch of shamanism.

As shamanism fell into disfavor in the Chinese court,8 Chinese medicine shifted ever more toward the technology of needles and herbs. Confucian scholasticism replaced shamanic intuition and energy sensitivity. The spiritual dimensions of Chinese healing were preserved almost entirely by the Daoists.9 Today most Chinese doctors dismiss shamanism as “superstition” (mi xin) and few have even heard of Zhu You or the branch of medicine he founded.10

Originally, EQH was called “Spreading Qi” (Bu Qi). Most specific references to the technique are in the works by or about Daoists. In the History of the Jin Dynasty [A.D. 265-317]: Record of Formulas and Techniques,11 we read, “Those who cultivate the Dao and nourish the qi are able, when their own qi is abundant, to spread qi to others.” This philosophy is elaborated in several Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) texts in the Daoist Canon, such as Master Huan Zhen’s Secret for Absorbing Original Qi. “To heal the sick by spreading qi, first locate where among the five organs the disease is located. Then inhale qi and project it into the patient’s body….This will drive out demons and poisons.” There is the Bu Qi Jing (Spreading Qi Classic) of unknown date. This text mentions a technique still used by External Qi Healers: to strengthen the dan tian, hold one hand on the patient’s navel and one opposite it on the lower back (ming men). The Daoists also recognized that a healer could affect the qi of even distant subjects. According to the fourth-century alchemist Ge Hong, “If someone far away has been bitten by a poisonous insect, exhale onto your palm and pray: your left palm for a man, right palm for a woman. The individual will be immediately healed even if he is a hundred miles distant.”12 Such distant healing effects of prayer and intent have been documented in Western medical research and lucidly analyzed in the landmark works of Dr. Daniel Benor13 and Dr. Larry Dossey.14

Many styles of EQH were developed or preserved within particular Daoist and Buddhist sects or monasteries. Some of these traditions are still transmitted only orally and have little written documentation. For instance, on Holy Mount Luo Fu in Guangzhou Province, Long-men Sect Daoists practiced standing and seated qi-projection meditations and developed a unique method of diagnosis.15 Since the Tang Dynasty (618-907), qigong techniques were widely practiced and prescribed at Buddhist monastic hospitals.16 Buddhist adepts may have also practiced EQH.17 EQH methods were also discovered by chance when qigong or martial arts masters attempted to heal their own students of illnesses or injuries.

There has been a renaissance of interest in External Qi Healing since 1980 when Qigong Master Lin Hou-sheng demonstrated the ability to induce anesthesia in surgery patients using External Qi. While Lin pointed his fingers at specific acupuncture points, the patient remained conscious and without pain during a thyroidectomy. Since that time, EQH has often been used to reduce pain during or after many kinds of surgery. External Qi anesthesia and EQH in general have become respected branches of Chinese medicine. Like internal qigong, EQH has gained in credibility and respect because it is capable of being measured and tested scientifically. It works on skeptics, laboratory animals, and cell cultures, allaying concerns that it is only placebo effect. When animals with broken bones are treated by External Qi, they heal more quickly than controls.18 We can assume that if an External Qi Healer inhibits the growth of cancer cells in mice,19 the therapy does not work because of the mice’s belief in the power and authority of the therapist!

PREPARING FOR HEALING

Healer: Heal Thyself!

The best preparation for External Qi Healing is regular practice of qigong, especially Standing Meditation.20 It is in this systematic self-training that EQH may have some advantage over Western varieties of healing touch. As you persist with Standing, your qi field becomes stronger and your sensitivity to qi imbalances becomes more precise. This means that you can have a stronger therapeutic effect on a client. Essentially, when you practice EQH, you are Standing. You are recalling the same physical and spiritual state. The spine is straight, the weight sunk through the feet, and you are breathing with the dan tian. The hands are filled with qi. Daoist texts advise that to master EQH you must also master Embryonic Respiration. This is because when the mind and body are quiet, they are the most receptive and capable of storing and transmitting qi. When the mind is free of turbulence, it becomes like the surface of a calm lake, a mirror reflecting things as they are.

A thirty-year-old American acupressure massage therapist, Scott, consulted me about how he might use qigong to strengthen and improve his treatments. He did not perceive that there was anything wrong with his technique, but realized that there is always room for improvement. Scott looked anorexic. He was very thin and pale. His eyes were dull, his voice so low that I could barely hear him, and his movements slow and listless. When I asked him how his patients felt after treatment, he said, “They always say that they are very relaxed.” “And how do you usually feel after a session?” He exclaimed, enthusiastically, “I feel great, full of energy.” This was an interesting situation. The patients were unable to distinguish depletion from relaxation. And the therapist was probably unconsciously addicted to the charge he got from treating his patients (no pun intended). The problem was easily corrected by a three-month program of Standing Meditation and a change in diet to include more yang, fortifying foods, such as meat and spices. When I saw Scott again he had gained twenty pounds and looked in better health. I am sure his patients were also benefiting.

Qigong practice keeps the internal qi pure and balanced, without excesses (too yang) or insufficiencies (too yin). These are important matters for energy healers. If the healer’s qi is toxic, stagnant, or congested, he might inadvertently transmit some of it to the patient, especially if the patient is weak and depleted. Energy tends to fill a vacuum, flowing from the positive to the negative. Or if the healer is himself depleted, he might either draw out the patient’s sickness and become sick himself, or perhaps even more disconcerting, he might absorb some of the patient’s own supply of healing qi. (I do not wish the reader to infer that if a healer feels better after a healing session than before, there is something wrong with the interaction. On the contrary, many studies have shown that healing heals the healer. Altruism of any kind is a powerful immune enhancer.) Unlike some forms of shamanic healing, the External Qi Healer never wishes to take on the patient’s sickness or to discharge it from his own body.

In summary, if the healer practices qigong, he will safeguard against:

-

transmitting toxins to the patient

-

absorbing the patient’s diseased qi

-

absorbing the patient’s healing qi

And perhaps the most important reason for External Qi Healers to prepare with qigong and meditation is that the healer, according to acupressure therapist Janet Murphy, “learns to tap into a Universal Well of Healing Energy.”21 According to two of the greatest spiritual healers of the twentieth century, Ambrose and Olga Worrall, “Too few in healing reach out to the pool of health and well-being that is all around us, the infinite sea, as available to us as the air we breathe.”22

The source of qi is not personal but transpersonal. It includes the healer, like a drop of water in the infinite sea. The healer needs to maintain an awareness of Place, a sense of where he is, not only how he is. He should seek the same state of harmony with nature whether practicing internal qigong or EQH. Simply maintaining connectedness allows qi to flow through rather than from the body. The healer funnels23 qi from a Source, sometimes identified as Nature, Dao, Great Spirit, or God. This belief is universal among all of the great healers, East and West. Again, the Worralls: “A spiritual healer is a person who is spiritually, physically, and biologically adaptable as a conductor between the source of supply and the patient. Under the proper conditions, healing energy will flow from the source through the healer into the patient.”24 Most healers agree that one of these “proper conditions” is compassion for the healee and a genuine desire to be of service. According to the Magus of Strovolos, an esteemed spiritual healer from Cyprus, “I assure you the more people you help, the more you fill up with vitality, assuming that you have love in your heart.”25

THE QI MACHINE: HOW TO STAY CONNECTED WITHOUT IT

Although there are many qigong healers who accept both the omnipresence of qi and an individual’s ability to tap into it, there are also many in China who do not. It is easy to become so fascinated by the movement of internal qi—the wiring of the human body—that one forgets to check if the human instrument is “plugged in” to its source of power. Qigong Master Lin Housheng warns that it may be dangerous to emit qi frequently, as this can deplete the healer’s own supply.26 An External Qi Healer and acupuncturist from the Shanghai School of Chinese Medicine expressed a similar viewpoint: “How can you use qi from nature? Where is nature’s qi? This is superstition. When you emit qi, you emit your own qi. That’s why I only treat patients with qi twice a week. At other times I use the Qi Machine.”

Many External Qi Healers now rely on this Qi Machine, a device that emits a qi-like field of infrared and other electromagnetic frequencies. No one claims that the machine produces qi. It only emits certain energetic correlates of qi. How these known aspects of qi affect the body in isolation from the unknown aspects is anybody’s guess. Although the machine is apparently effective for pain, headaches, and other conditions, it is immature and weak compared to EQH, for several reasons:

1. Unlike a human being, the machine cannot modulate the strength or range of the field from feedback it receives from the patient during the ongoing process of healing. The machine does not know when the patient needs more or when he has had too much.

2. The development of this technology may be founded on wrong assumptions: that a human being must use his or her own limited resources in any therapeutic interaction, and that practitioners will always be relatively rare or inaccessible because it takes so long to develop the ability to emit qi.

3. This technology has not been in use for sufficient time to determine if there are any harmful side effects or contraindications.

4. Scientific evidence suggests that healers cause resonant effects in the patient, like one tuning fork causing another to vibrate. Who wants to resonate with a machine? In the third century B.C. the Daoist sage Zhuang Zi warned against becoming “machine minded.”

5. A mechanical healer, unlike a real one, cannot use intent or visualization to project qi to a distant patient. The Qi Machine’s healing ray is neither as powerful nor as precisely targeted as a human being’s.

6. The human qi-field or projected qi-wave may be encoded with mental and emotional content, carrying information and positive thoughts/feelings from the healer to the patient. If so, then a Qi Machine would be incapable of producing similar therapeutic effects. Additionally, although energy is certainly a measurable correlate of qi, perhaps some healing effects are a product of consciousness itself, without any need to posit an intervening energy.

An External Qi Healer will not be in danger of losing qi provided he is committed to keeping his circuits unbroken, grounded, and properly insulated. “Unbroken” implies harmony and communication between the inside and outside (self and environment), upper and lower body, conscious and subconscious, and right and left (including the intuitive and analytical hemispheres of the brain). “Grounded” means having your feet on the ground, taking long walks in nature, enjoying physicalness: your own body and the world. “Insulated” means setting limits, not allowing yourself to get exhausted or scattered, knowing when you need to turn inward and away from stressful situations. Insulated does not mean insulated from…insensitive to….Rather, it implies self-caring and inner-nourishing.

Being committed to these principles does not mean that you will always live up to them 100 percent. That would be a human impossibility. Rather, the dedication to these ideals and the regular effort at achieving them will ensure that the External Qi Healer is functioning with optimal potential and safety.

HEALING ENVIRONMENT

In addition to preparing himself energetically, the healer needs to cleanse the space itself of noxious qi. This principle was understood by the ancient Daoist healers who performed healings in beautiful mountain hermitages or in front of an altar, sweetened and cleansed by plumes of incense smoke; today, the healing environment is ignored or considered irrelevant. This is as true among modern Chinese acupuncturists as among Western health-care providers, whether physicians or naturopaths. Allopathic medicine focuses on the disease the person has. Holistic medicine prides itself on emphasizing the person who has the disease. Both tend to ignore the fuller context of healing: the environment of the patient.27

The relation between qi and space is a matter of common sense. Have you ever walked into the home of someone who is ill or in a bad mood or who recently argued with his wife—and sensed that something isn’t right; the room’s energy feels imbalanced or toxic. The same thing can happen when a client arrives for EQH or any other form of therapy. He or she may be affected by the toxins that were discharged by a previous client.

Today, it is impractical to make pilgrimages with our patients or to expect them to visit remote locations. The next best thing is to bring nature to them by using her healing power to purify and energize our places of treatment. This can be done a number of different ways. In China, it would be proper to burn Chinese incense. However, only a local herb can affect the qi of an area. I recommend that Americans burn Native American incense—sage, cedar, or sweetgrass. Respectfully gather whichever of these is local to your area.28 Dry the plant, then burn a little bit in a container or shell. Make sure that a door or window is ajar, so that negative qi can exit. In order to prevent subtle energy pollution, you should imagine that this noxious energy turns into divine light or sinks into the earth as compost. Another way to purify a room is to wave candlelight through it. If you live near the ocean, you can sprinkle ocean water to the four directions, using a tree branch or large leaf. (This method was also practiced in China, using a willow branch.) Finally, you can imagine a natural healing power suffusing the room—for instance sunlight, moonlight, or a spring breeze. This last method is generally not as effective as the others, unless your powers of concentration are very strong.

Cleanse your space before seeing any clients and between clients if you are working professionally. I recommend this to all health-care providers.29

BUILDING TRUST

Chinese works on EQH agree that the patient can most easily absorb qi when he is relaxed and free of worries. However, if the patient is tense, it is not enough for the doctor to say, “Relax.” That’s like telling someone to float when he’s sinking in panic. Rather, relaxation is contagious. The patient will catch it if the healer is relaxed, centered, and calm and if the healer interacts with the patient as one human being with another, rather than from an aloof position of power and authority.

Chinese healers can take a lesson from Mexico’s folk healing tradition, curanderismo. Firstly, the patient must ask for healing. The curandera (healer) does not missionize her healing ability. She is not permitted to say, “Come, I can heal you.” If the patient doesn’t ask, he can’t receive. And very importantly, if the patient has not given permission for healing, his energy may be hidden, not as available for purposes of assessment or treatment. One time in a curanderismo training class, a student asked the curandera, “Can you read my aura?” She replied, “If you let your aura out, then I will read it.” If, however, the patient is a child or someone incapacitated and unable to ask, then the curandera does not need verbal permission. Instead, as in all healings, the healer must ask her own intuition, “Can I help? Is this patient ready for the kind of healing I practice? Should I make a referral?”

When a curandera greets a patient, there is a warm handshake or embrace. Then they talk about everyday concerns. “How are your children? Are you happy at work? Would you like some coffee?” Gradually and subtly they shift into the matter of healing. Healing is treated as everyday rather than esoteric, and it is certainly not a mere business, a cold exchange of commodities. The healer needs to help the patient feel comfortable, relaxed, and cared for.

Remember, before you begin an External Qi Healing session:

-

Practice qigong and meditation

-

Cleanse the space

-

Build a trustful atmosphere

-

The patient must ask (unless incapable)

ASSESSING IMBALANCE

General Assessment

In EQH, the client can remain fully clothed, unless EQH is being combined with Swedish or other massage therapy. It is helpful if the client removes jewelry and shoes.

There is a Chinese saying, “The master physician writes the prescription as the patient walks through the door.” How is this possible? If the doctor has trained his/her qi sensitivity to a high level, then he receives a very clear energetic first impression. This first level of assessment is called qi se, “qi appearance.” The healer may even feel as if he is seeing the patient’s imbalance (tou shi zhen duan “diagnosing through penetrating vision”). Chinese tradition claims that the great physician, Hua Tuo, was a master of this technique. He could see the patient’s internal organs. (X-ray machines seem primitive by comparison!) However, I believe that the doctor does not so much “see” as feel. He feels the qi se; he feels the emanations from the diseased area. A healer might also notice discomfort in the same part of his own body. The feeling is interpreted and translated by the mind into an appropriate image. This is sight only in the sense of “insight.”

There are many factors involved in qi se: the color of the skin; quality of movement, breath, and voice; the sound of the footsteps; and a general feeling of fullness or depletion of qi. Make a mental note of the qi se of the patient; it indicates the patient’s general state of health or disease. Your ability to form this impression will grow as you advance in qigong. Later, you can use various assessment tools to corroborate or determine the accuracy of this impression and to gain more detailed information.

Next, I like to practice “laying on of hands” on energy centers or assessment areas to get a more physical and powerful impression of the client’s qi. Although not specified in EQH texts, I have found that noncontact treatment is more effective if preceded by some form of physical touch. The warmth of the therapist’s hands helps the patient to relax. As strange as it may sound, touch is often perceived by the patient (even those unfamiliar with energy medicine) as less invasive than noncontact treatment. Touch communicates caring; noncontact treatment is more obviously an attempt to change or correct the body’s underlying energetic program. The only time when the therapist may need to avoid any form of physical contact is with patients who have suffered physical, emotional, and, most significantly, sexual abuse. For these individuals, touch is often perceived as a threat and an invasion of privacy.

What are these assessment areas of the body?

WITH CONTACT

The client is seated in the middle of a stool or kitchen chair, his or her back not touching the backrest. Use any or all of the following:

Method 1: The Spinal Touch. Place one palm (either hand) on the spine, opposite the navel (ming men point). The other palm rests on the spine just below the seventh cervical vertebra (da chui point). Keep the hands there for a few minutes, until you have some sense of the temperature, the vibratory quality of the qi, and any other subjective impressions. Does the energy feel superficial or sunken; is it smooth or coarse, choppy or flowing, warm or uncomfortably hot, cool or deathly cold? Note also if the upper or lower body seems more energized. As you practice with more and more clients and compare your findings with the patient’s presenting symptoms or medically diagnosed problems, you will gradually develop the ability to interpret your subjective feelings of qi.

Method 2: Dan Tian. Another area that gives a general and overall indication of the qi level of your client is the dan tian. Place one palm just below the navel, the other palm opposite, on the back. Feel how the breath moves or doesn’t move between your hands. Is the body tight or relaxed? You may also feel vital heat and qi.

The dan tian is the place of power and loss of power. It is a sensitive, vulnerable area, connected with sexuality. When children are invalidated, they learn to hold and constrict the abdomen. These tensions often persist into adulthood. For this reason, holding the dan tian can give you information about the client’s self-worth and degree of empowerment. I have found it best to assess qi here only with clients whom I have already seen a few times and who do not perceive touching this area as threatening and frightening.

Method 3: Lao Gong. To get a sense of peripheral qi and blood circulation, lightly hold the lao gong point in the center of the palm. Touch the point with your thumb, the other fingers touching the back of the client’s hand. You may feel both temperature and a gentle pulsing. With practice it is also possible to intuit the emotional state of the client through this point. It is directly connected with the energy of the heart.

WITHOUT CONTACT: THE ENERGY SCAN

The client can be seated or lying down. Position your palms about six inches away from the surface of your client’s body. Then experiment to find a distance that allows the greatest sensation of qi. The distance may increase or decrease as you move over the body, following the contours of the energy field. When an area is too yang, the hands will push away. When an area is too yin, the hands will draw closer to the body. It does not matter if you start at the front or back, the head, feet, or center of the body. Follow your intuition. Remember that you are still not trying to change or correct the qi, only to sense it. If your client was lying on his back, he will need to lie on his front when you assess the other side of the body.

Differential Assessment

In Chapter 4, “Qigong Science,” I discussed how researchers found that changes in skin conductivity at specific acupoints on the fingers and toes correspond to states of health or pathology in associated organs. These points are actually the first or last points of the organ meridians, places where the energy of the meridian peaks. What these scientists may not have realized is that they were validating an ancient Daoist method of diagnosis.

The ends of the fingers and toes are lightly grasped, one at a time, between your thumb, middle, and index fingers, while the other hand is held a short distance away from the corresponding organ. You do not have to know the exact location of the acupuncture points. Instead, the practitioner touches the general area of the point, around or on the nail. Since the other hand is placed directly above the organ, the method requires only general knowledge of anatomy and can be practiced by those unfamiliar with the location of acupuncture meridians.

Diagnose a man on his left side (using his left hand and foot), a woman on her right. The client can be lying down or seated. It does not matter which hand holds the finger/toe and which is directed over the organ. While assessing the qi, look for three characteristics:

1. Temperature: Hot, cold, or comfortable (pleasantly warm). Hot means too much qi, congested, or stagnant. This often indicates infection or inflammation. Cool means weak and depleted. Comfortable temperature generally indicates health.

2. Rate: Quick or slow pulse or vibration, smooth and even or broken. Of course, the ideal is a smooth, even pulse.

3. Subjective Quality: This can take almost any form. The energy might feel pointed, sunk, coarse, cheesy (congested), angry, depressed, tranquil, etc.

REFLEX AREAS ON THE HAND (FIG. 61)

• Thumb—Lungs. Hold the man’s left thumb tip, the woman’s right thumb tip with either hand, the other palm above the lungs. Do an energy scan of both lungs.

Figure 61

• Index—Large Intestine. While holding the tip of the index finger with one hand, the other slowly moves above the large intestine. You can also visualize the organ. This will make your hand position more accurate.

• Middle Finger—Pericardium and Reproductive System. The same fingertip is used to tune in, sequentially, to two areas of the body. As you hold the tip of the middle finger, your other hand goes first to the heart. Although this point is related to the pericardium (the membranous, fluid-filled sac that encloses the heart and the roots of major blood vessels), it is practically impossible to distinguish the pericardium from the rest of the heart. So we should consider this as part of heart qi assessment. There will be a second heart reflex area on the little finger. Next bring your palm over the reproductive system: genitals, ovaries, prostate, wherever appropriate.

• Ring Finger—Triple Heater and Thyroid. As you hold the triple heater area, the other hand moves gradually over the upper, middle, and lower torso, from the front or back of the body. Note the warmth and qi quality of the three areas to determine which is relatively full or depleted. Then bring your palm above the thyroid. A feeling of uncomfortable warmth or pressure may indicate hyperthyroidism; too little energy may indicate hypothyroidism.

• Little Finger—Heart and Small Intestine. As you contact the tip of the little finger, the other hand senses first the heart qi, then the small intestine.

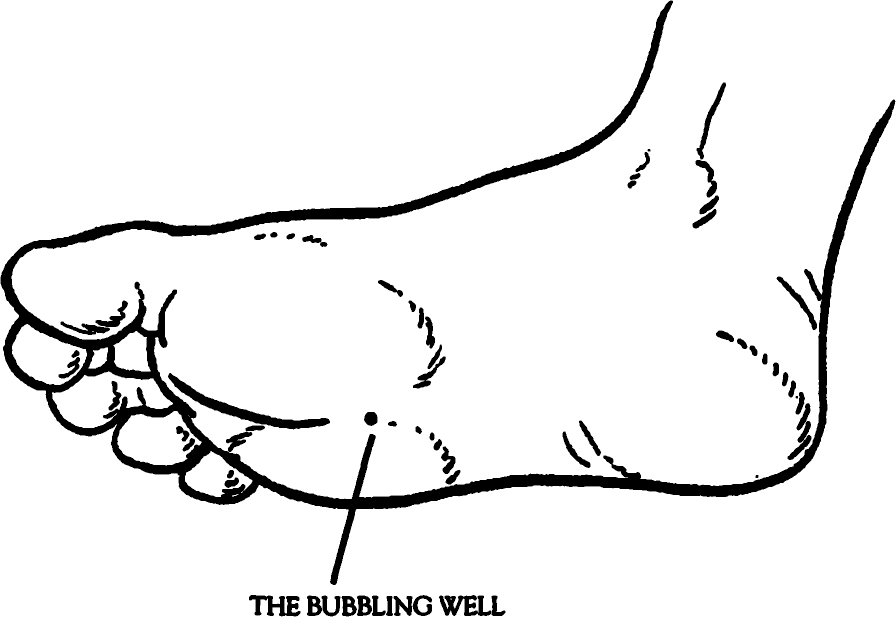

REFLEX AREAS ON THE FOOT (FIG. 62a)

• Big Toe—Liver and Spleen. Holding the end of the big toe with the thumb, index, and middle fingers of one hand, the other palm is positioned above the liver, sensing the qi. Then move your palm to the spleen. The procedure is similar for each of the other toes.

• Second Toe—Stomach.

• Fourth Toe—Gallbladder.

• Little Toe—Bladder.

What happened to number three? Am I missing a toe? The third toe does not have a beginning or ending meridian point and is not used to diagnose organ health.

Finally, to tune in to the qi of the kidneys, lightly touch the “Bubbling Well” point (figure 62b) on the sole of the foot, one-third the distance from the base of the second toe to the back of the heel. The other palm reaches behind your client, feeling the kidney qi.

Figure 62a

Figure 62b

Putting It All Together

You have learned four methods to assess imbalance in qi. 1. Qi se, for a general impression. 2. Light contact on any of three assessment areas (spine, dan tian, palm). 3. Noncontact scanning. 4. Differential assessment using points on the hand and foot. Proceeding in this order, each method adds to your database, giving you more details about what you sensed while applying the previous technique.

For instance, a middle-aged male patient walks into your office. You notice immediately that his movements are determined and aggressive, his face slightly red. The qi se suggests heat, fire, perhaps a “false yang,” masking or compensating for inner depletion. When you place your palms on his spine, there is a great deal of surface warmth, with much more warmth on the upper back. You think, Yes, this does seem to be a condition of excess yang, and, in general, too much energy in the upper body, too little in the lower. Then, during a noncontact scan, your hand feels pressure over the heart and liver, and coolness around the kidneys. The finger-toe method confirms your impression: heart and liver hot and yang, kidneys weak.

If you are a health-care professional, you will compare your findings with other systems of diagnosis. For example, a Chinese doctor might feel the pulses and look at the tongue fur to determine the health of the organs. A physician will compare her qi assessment with information received through the stethoscope, EKG, blood work, and any other necessary tests. She might find that the patient above has elevated stress hormones (“adrenal burnout”), arteriosclerosis, high cholesterol levels (possibly due to a liver malfunction), and a type A personality.

The more you compare your qi assessment with the patient’s health history and with standard diagnostic measures—whether from allopathic medicine, chiropractic, Chinese Medicine, or other healing systems—the more you can refine your qi sensitivity and diagnostic abilities.

Now the question is, how do you treat the problem?

TREATMENT STRATEGIES

De Qi: Reaching the Qi

In all aspects of External Qi Healing, whether diagnosing or treating, the most important principle is de qi “reach the qi.” This means that your hands reach energetically through the clothing, through the skin and tissue, to the underlying life energy, the qi. In China, where patients are more familiar with the electrical sensations associated with qi flow, a beginning acupuncturist will commonly ask her patient, De qi le, mei you? “Have I reached the qi?” If the needle is inserted too superficially, it is only in the skin; if too deeply, it can penetrate or damage nerves or other tissues. If it misses the point entirely, there may be pain but no “electricity.” The acupuncturist proceeds gradually and may ask the patient for feedback. Essentially, she is asking, “Am I on target?” Later, as the acupuncturist becomes familiar with the electrical, almost vibratory energy that is emitted from the needle, she no longer needs to ask the patient. She can feel the qi.

In External Qi Healing, there is no instrument between the healer and the healee. The healer senses the qi directly with the hands. The healer changes the depth of penetration of her touch not by increasing the pressure of the hands on the skin but by maintaining a calm yet energized qigong-state and simply intending to reach in.30 She knows when she has de qi because she senses vibration, warmth, and an indefinable feeling of energy on the patient’s body or in his qi field. When the healer feels that she has reached the qi, the patient usually feels it also. It is not uncommon for the patient to exclaim, “What did you do? Your hands suddenly feel like a heat lamp!”

Making Contact: Healing Through Sensing and Yin Yang Polarity

Placing the hands on or above assessment areas is obviously more than assessment. It is the beginning of treatment. Sensing is healing! When we interact with another, there is no way to absolutely assess the state of health. As we sense qi, the qi changes and moves toward balance. The observer changes that which is observed. This is why it is important to remember your first impressions and to note how this impression changes as your hands remain on or above assessment areas. The degree of change may be predictive of the patient’s responsiveness to therapy.

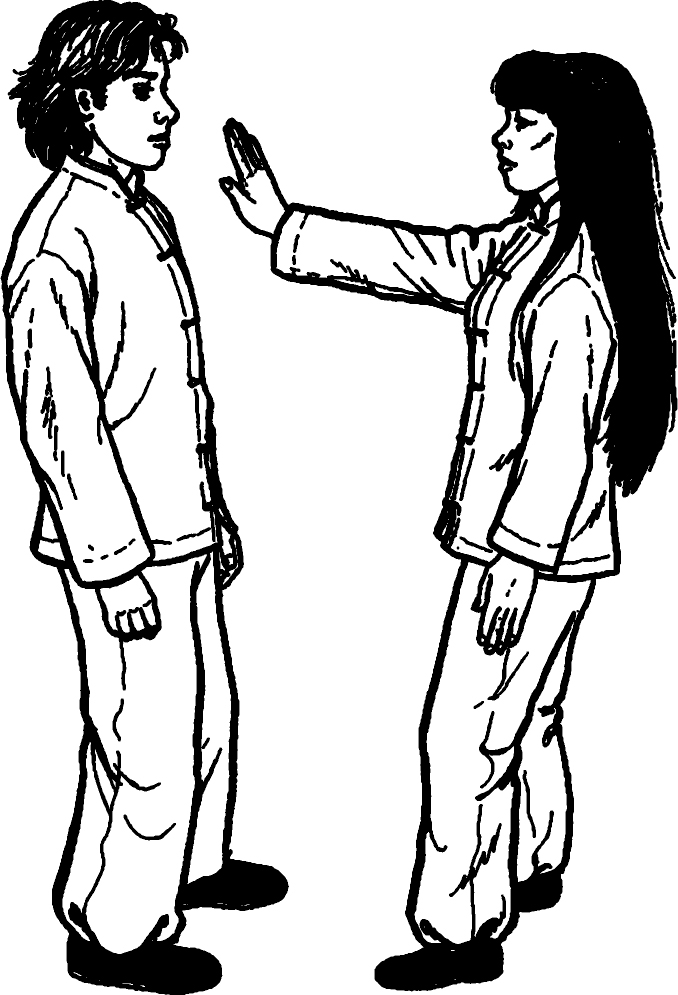

Sensing, making contact, is the first, safest, and most important method of treatment. After finishing your assessment, return to the places of imbalance—areas where you felt excess, deficient, or diseased qi. Place one or both hands either on that area or in the qi field above it. One of the most effective ways to apply sensing is to position the hands on either side of a diseased area, as though you are doing Standing Meditation with the patient between your palms. I call this method “Yin Yang Polarity.”

For example, if the patient has a diseased liver, then one palm can be held in back of the liver, one in front, several inches from the patient’s body (fig. 63). Don’t worry about projecting qi. Just do your Standing Meditation. You are actually doing qigong together. Your qi field, interacting with that of the patient, communicates a healing message. Unlike Western biotechnology, this method requires awareness and intent on the part of the practitioner. The healing message is stronger in proportion to the depth of the healer’s centeredness and ability to connect with the patient and with universal qi.

Figure 63

Adapt the Standing Meditation posture to the position of your patient. If your patient is seated or lying on a massage table, it is difficult to reach the patient unless you squat very low or bend your back. This is uncomfortable and awkward and will decrease the amount of qi available. Instead, sit next to your patient. Keep your legs uncrossed, your feet flat on the ground, back straight, breath sunk, and arms rounded. Maintain all of the principles of Standing Meditation from your seated position.

When should you use Healing Through Sensing or the Yin Yang Polarity? These methods may be used for any kind of condition, whether congested (yang) or depleted (yin). It is always the safest method of treatment when you get a confusing impression and are unsure exactly what the problem is. Because the healer is not trying to change or manipulate the patient’s energy in any specific way, there is almost no chance of doing harm. For some EQH patients it may be necessary to use only Healing Through Sensing. Generally, I like to begin and end all EQH sessions with Sensing.

Correcting Imbalance: Circling Palms

To understand the principles of transmitting therapeutic qi, try the following experiment. Ask a friend to hold out his left hand, palm up. Place your right palm a few inches above his hand, finding the distance that allows maximum qi sensation. Now as your partner’s hand remains still, slowly rotate your right hand in tiny counterclockwise circles, as though the center of your palm is a laser beam, drawing a circle around your friend’s palm. Then increase the circumference of your circle, so that your palm is shining light on each of your partner’s fingertips and then moving down to the top of the wrist. After several circles, reverse direction, circling clockwise. Ask your friend what he or she felt. Was there a qualitative difference between the two circles, counterclockwise and clockwise? Let your friend try the experiment on you. Is your experiment replicable? Try it with other friends and see if you get the same results. What sensation is produced by counterclockwise circles, what sensation by clockwise circles?

You have already discovered the first principle of therapeutic noncontact treatment. Counterclockwise is cooling (yin) and reduces heat, inflammation, fever, congestion. Clockwise circling creates warmth (yang) and adds energy and stimulation to weak, cold, and depleted areas. If an organ or area feels hot or over-full, use counterclockwise circles, circling above it several times, until you sense that the area is responding maximally and returning to a more normal temperature. If the organ feels cool or deficient, circle clockwise. If you are unsure, use Healing Through Sensing.

Figure 64

Whereas most EQH treatment methods can be applied with both hands at once or either hand individually, circling palms is best performed with only one hand, called the yang hand. It does not matter which hand is used to project qi. Some healers prefer the right, some the left, some are ambidextrous, or at least energetically so, and will use one hand or the other according to their mood. The other hand, the yin hand, is relatively passive. It is not used to treat or project qi, but rather rests at the side of the body, fingers pointing toward the earth. The yin hand connects with the energy of the earth. Like the healer’s feet, the yin hand helps the healer stay grounded. It will also automatically discharge toxic qi from the healer’s body or draw extra healing energy up into the body if there is a need for it. There is no need for the healer to think of emitting or absorbing qi with the yin hand. This will happen by itself if the healer is relaxed and rooted. Both hands are simultaneously practicing de qi. The yang hand reaches the qi of the patient; the yin hand reaches the qi of the earth (fig. 64).

The circling palms method of treatment is identical to that used by indigenous people. When I explained to my Cherokee mentor, Keetoowah, about EQH methods, he looked at me in disbelief: “How could Chinese people know about Cherokee medicine?” Keetoowah used to hold his hands in front and back of the patient’s body, “like two poles of a magnet, the negative and positive.” Sometimes he would circle one palm—clockwise to warm the body, counterclockwise to cool it. His other hand was usually pointed toward the ground.

Tapping, Pulsing, Waving

Other effective treatment gestures include Tapping, Pulsing, and Waving. Tapping means to lightly and rhythmically tap or pat the qi field with either your palm or fingertips. This is useful to relieve stagnation or congestion and to improve circulation. In Tui-na, Chinese Massage Therapy, tapping is applied directly to the body for the same purpose. The therapist taps with either fingers, palm, back of the hand, side of the hand, or fist to produce varying degrees of stimulation.

Pulsing means to ever so slightly open and close the palm. Stretch the fingers and hand open, then let it relax. Do this repeatedly at a steady pace. The qi is emitted from the center of the healer’s palm. The indications for pulsing are similar to tapping. It stimulates and improves circulation. Pulsing can be used over any area of the body that requires it, including specific acupuncture points. If you pulse directly over an acupuncture point, it is easy to feel tingling and warmth at the point or radiating along the meridian.

Waving is very useful for congestion or pain. The fingertips sweep down the patient’s energy field, as though brushing the pain away. The technique is identical to the “Sweeping” (barrida) practiced in Mexican curanderismo healing.

These three methods move qi without adding heat or cold. They can be applied by themselves or combined with clockwise or counterclockwise circling. For instance, if the kidneys are weak and deficient, it may be necessary to use gentle pulsing of qi, followed by clockwise circling. If the shoulders are tight, painful, and hot, you can use counterclockwise circling to reduce tension and waving to relieve pain. For an inflamed, sore throat, you may wish to circle counterclockwise over the throat and then sweep the pain away from the body.

Hand Position

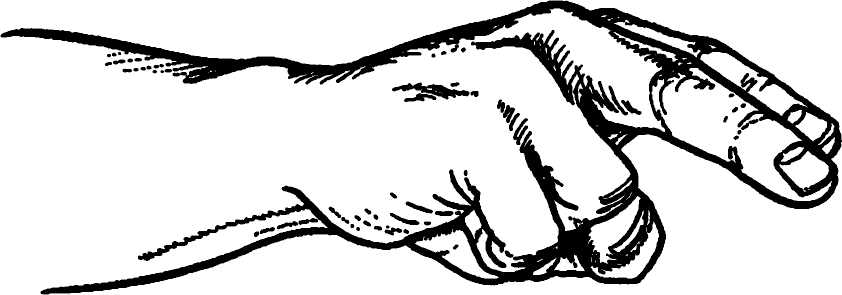

Usually the entire open hand is used to transmit qi. Qi is emitted from the fingers and palm over a broad area. To intensify the “qi beam,” emit qi from

Figure 65

Acupuncturists or those familiar with Chinese medical theory can use the most specialized hand gesture, known as “sword fingers” (jian zhi) to direct qi into specific acupuncture points. The index and middle fingers are gently extended, with the thumb and last two fingers bent into the palm (fig. 65). Here the EQH therapist is actually doing acupuncture without the needles. The sword fingers circle counterclockwise to sedate the energy of the point or clockwise to tonify it. The sword fingers can also tap by moving slightly away from and toward the point. It is also possible to combine EQH with acupuncture. Acupuncturists generally twirl or poke the acupuncture needle to change the quality of stimulation at a specific point. Acupuncturists trained in EQH leave the needle in place and while holding their sword fingers a few inches above the needle, tonify, sedate, or stimulate the point with appropriate EQH gestures.

DURATION AND FREQUENCY

The length of treatment can vary a great deal from patient to patient, depending on what the patient is capable of receiving. For some, five minutes is sufficient. For others, forty minutes is necessary. The therapist can judge the patient’s receptivity and degree of satiation (with qi) by noticing changes in the patient’s skin color and respiration. If the skin becomes very red or very pale or if the breathing rate becomes consistently quicker, the patient is uncomfortable. If the therapist is capable of de qi, she will also be able to feel when the energy is no longer received. At some point the therapist may feel as though the same poles of a magnet have been brought together. Instead of attracting her qi, the patient repels it. Obviously, the treatment should be closed.

The most important indication of satiation is the patient himself. He needs to know that it is acceptable to inform the therapist if a treatment feels inappropriate, excessive, or insufficient. I have found that when therapists continue EQH against the verbal or nonverbal permission of the patient—with an attitude of “I know what’s best for you”—both therapist and patient can become ill. The patient is constipated with unassimilated qi. The therapist is hit by some of her own returning qi, now tainted by the toxic qi field of the patient.

Some patients will experience significant improvement after the first session. Most patients notice definite changes by session four or five. Acute problems are more likely to respond quickly. Long-term, chronic conditions will require a longer course. For instance, I have found that car accident victims with brain injuries usually experience subjective qi sensations after a few sessions, but require anywhere from four to six months before their condition improves according to objective measures. Treatments are generally given once a week. If the condition is very serious, the patient can be treated more frequently.

As with any therapy, not all patients are cured; however, unlike patients treated by allopathic interventions, almost all individuals who receive EQH experience improvements in quality of life, including better sleep, more energy, improved appetite and digestion, and a healthier attitude. In the long run, these qualitative changes may have a stronger effect on the course of serious disease than any specific therapy.