Fort Zachary Taylor flying the Stars and Stripes. Construction was still ongoing here when Florida seceded from the Union. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

CHAPTER 3

CONFEDERATE CONCHS ENLIST

One of the most dramatic—and better-known—exploits to occur in the Florida Keys during the Civil War period took place when, on January 13, 1861, shortly after midnight, an army captain named John Brannan slipped his troops from their barracks on the northeastern side of Key West.67 “In the dead of night,” one soldier later recalled, Brannan secretly marched the men “by a route avoiding the town” to Fort Zachary Taylor on Key West’s western shore.68 The troops brought with them as many weapons and as much ammunition as they could carry.69 There Brannan met up with Captain Edward Hunt’s meager forces, mostly engineers and Northern laborers who had agreed to help, and together the assembled men seized the still-as-yet-unfinished Fort Taylor and barricaded themselves inside. Brannan’s own force may have consisted of only forty-four men (while the island’s white population numbered more than two thousand),70 yet stored inside the fort were seventy thousand gallons of fresh water and “food provisions enough to last four months.”71 From behind the safety of its walls, and separated from the island by a narrow spit of land, the fort’s armaments could fire on any insurrection in town and defend against an incursion by sea. Key Westers awoke the next morning to a new reality: their town had fallen under the control of the U.S. Army. With this single action, Brannan ensured that America’s southernmost city and a strategically important port in Confederate Florida remained firmly in possession of the North.

Fort Zachary Taylor flying the Stars and Stripes. Construction was still ongoing here when Florida seceded from the Union. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

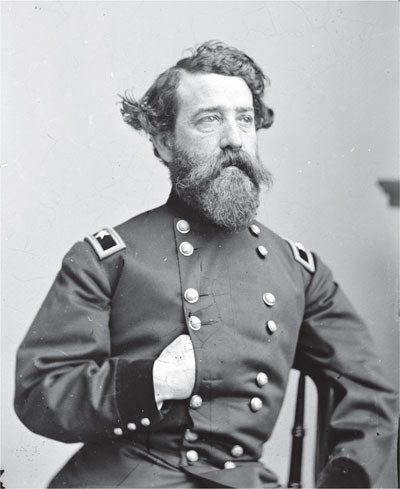

Army captain John Brannan acted decisively after news of Florida’s secession reached Key West. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Captain Brannan, forty-two years old with exuberant waves of dark hair and a resplendent beard and mustache, had responded decisively to changing events. Ever since the election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860 (when Lincoln won the electoral college but only 40 percent of the popular vote), Southern states had grown increasingly agitated; secession loomed not as a theoretical exercise but as a concrete possibility. Florida’s governor picked January 3 for a convention to decide the state’s future: remain with the Union or secede. In Key West, Monroe County’s bigwigs, all white men, met to elect delegates; pro-Union man Walter Maloney Sr. was outnumbered by pro-secession voters, and the islands’ delegates—Judge Winer Bethel, William Pinckney and Asa Tift—intended to vote for Florida to quit the United States.72 On January 10, in the Tallahassee capitol, the Florida Keys representatives along with fifty-nine others voted for and then on January 11 signed the Ordinance of Secession.

In those days, news traveled to Key West by schooner and sloop, not television or Internet. It would have taken two days for Key Westers to learn the result of the state convention. As the convention’s outcome reached the island, Captain Brannan quickly grasped the significance of the situation. The U.S. Army forces in the barracks and the men working to complete Fort Taylor were thick in the midst of enemy territory. Brannan, with Captain Hunt’s encouragement, did not wait for approval from Washington. He took the initiative and, in about six hours, secured a highly strategic location for the U.S. government.

These events are well documented and certainly not “hidden,” but this episode provides important context for what will follow later. Because we know that Union troops secured the island months before the Rebel attack on Fort Sumter, it was conceivable that Key West’s citizens would embrace their new status as a Northern stronghold in a Southern state. Although some Southerners resided in the Keys, many residents hailed from the Bahamas, New England, Cuba and even Europe. Why would Yankees and foreigners support the South? It would be natural to assume that Key West and its multi-ethnic citizenry spent the duration of the Civil War as a cooperative, loyal Union outpost. But surprisingly, some Key Westers, along with settlers at Indian Key and Key Vacas, were not united behind the Union. In fact, it was in light of widespread Confederate sympathies that Brannan acted so swiftly, taking Fort Taylor and then reporting to his superior, “I have placed my entire command in Fort Taylor for the purpose of protecting it. I shall, until orders from the General Government to the contrary, defend it.”73 Later in February, the captain did not “apprehend any attack on this fort,” yet he observed pro-secession flags flying over several shops.74

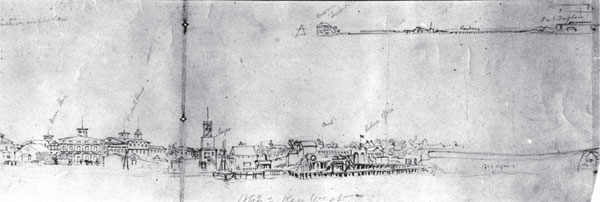

A sketch of the Key West waterfront during the Civil War. Courtesy of the Monroe County Public Library, Key West.

The War Between the States, the War of Rebellion, the Civil War—call it what you will. The conflict that would erupt a few months later would find neighbor divided against neighbor and brothers enlisting to fight their own brothers. Key West was no exception. Fervent supporters of the Confederacy found themselves in opposition to Unionists whom they had known and befriended over decades, and at least in one case, the terrible war would pit a father against his own son.

One of the early troublemakers for occupying Union forces was Henry Mulrennan, a tall, good-looking military veteran originally from Scotland.75 As a Key West shopkeeper, he embraced the South’s cause with all the enthusiasm of the newly converted. About two months after the events at Fort Taylor, Mulrennan hoisted a secessionist flag (possibly the Bonnie Blue, blue with one white star) at his store. Unfurled against the clear March skies above his wood shingle roof, the flag fluttered like a provocation to the Union forces. In a letter to Captain Brannan,76 Mulrennan wrote, “The flag of the Republic of Florida having been hoisted this day and properly saluted by military officers holding commissions under that republic, we consider you gentlemen enough to acknowledge it accordingly.” He had the audacity to add, “P.S. You will treat the bearer [of this letter] with all the courtesy due to military men.”77 If Mulrennan expected his flag to be saluted by Brannan, he was in for a disappointment. His pro-Rebel agitating did not end there, however, and by June, with the war underway, the man was arrested (or possibly just threatened with arrest) and forced to leave Key West as a result of his “treasonable and seditious language.”78 Although Henry Mulrennan disappears from some Key West accounts at this point, he would reemerge later.

Mulrennan was not the only one unable to abide the Union occupation. Key Wester Robert Watson wrote in his diary in September 1861, “Owing to the political affairs of the country and the Federal troops having possession of this place and as it is rather unsafe for a southern man to live here I have determined to leave in disgust.”79 Twenty-six-year-old Robert worked as a carpenter, probably doing a good amount of work on ships; his family had moved from the Bahamas to Key West when he was an adolescent, and now this naturalized citizen prepared to take up arms on behalf of the South. Certain other able-bodied men in the Keys felt just as impassioned as Watson and were ready to join the rebellion. Local clerk Alfred B. Lowe and his friends, including Watson, applied for the necessary passes to leave Key West.80 The Union authorities, aware of pro-Southern sympathies among part of the population, were not about to let them simply quit the island and join the ranks of the enemy. The new commanding officer, Major French, demanded that they swear an oath of allegiance to the Union. This the group of pro-Rebel Key West men would not do, and their applications were therefore denied.

If Major French believed he had outwitted the Key Westers, he was very much mistaken. In the previous month, Confederate hopes had been buoyed by a victory at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in Missouri. Throughout the South, enthusiasm for “the Cause” was running high. Not only did a number of Key West men feel called to serve in the Confederate military, but they also knew the surroundings seas as intimately as any men alive and had connections at the wharves and among sailors and captains. Major French’s heavy-handed tactics provoked these Key Westers into setting out on the greatest adventure of their lives.

That September, Robert Watson, fellow Bahamian William Oliver Sawyer, Italian Marcus Oliveri and Peter A. Crusoe, the oldest at forty-one years and previously the clerk of the circuit court at Key West, managed to stow away aboard a British ship. Given Watson’s subsequent diary entries, it’s clear that the men could only have done this with the collusion of the captain, who may very well have been sympathetic to their cause. (The men went on land without difficulty when the ship anchored in various harbors, something they could hardly have done without both captain and crew becoming aware.) On September 27, Watson recorded that “I left today in the schooner Lady Bannerman for the Bahama Islands, in the company with Canfield, Sawyer, Lowe and several others. The schooner has on board 55 passengers in all, the most of which are women and children.”81 We don’t know whether the men revealed their plans to their families, who would have pressed on them bundles filled with food and money, or whether they left without saying goodbye. Secreted in the Lady Bannerman, they sailed from Key West and in the Middle Keys stopped at the small, mostly Conch-settled82 Knight’s Key, where the numerous family of Temple and Mary Pent made their home. Then the Lady Bannerman put in at Indian Key (in present-day Islamorada) where Watson gleefully recorded, “I and Eggleston Curry got a lot of whisky; all hands took a drink and proceeded on our voyage.”83

The journey wasn’t all shore leave and drinking. More than once on the voyage Watson fell ill and felt like he might die. Eventually, he and his band spotted the tiny Bahamian isle of Orange Key, and the following day, on October 3, 1861, they “laid to off Sandy Key [Cay].” Here, Watson’s hunger got the better of him: “[I] got a lot of conchs and as my appetite was very keen I ate many conchs, stewed conch, fried conch, and roast conch and tapered off on rum.”84 The Key West runaways eventually landed on Bahamian soil, first at Green Turtle Cay and then northeast of Eleuthera at Harbour Island.

Watson and his Key West companions may have experienced a brief moment of jubilation at being on neutral territory, freed from the dictates of U.S. military commanders. But their next move was not necessarily a simple one: how were they going to make it from this tiny Bahamian isle to a Southern town where they could enlist? Some of the Key Westers, including Robert’s brother, George Watson, decided first to rest and recuperate on Harbour Island (famous for its unusual pink sand), while Watson and Cyrus Canfield continued on to Nassau. After eight days of waiting for their compatriots in Nassau and “finding that our pockets were getting low,” Robert and his friend Canfield decided not to wait any longer. He’d gotten word that his brother and other friends had returned to Key West. So the two of them, Watson and Canfield, “engaged to work our passage in an old leaky schooner bound for Jacksonville, Fla.”85 The journey on such an unreliable boat proved hair raising: “Every little squall our sails would split and ropes give way and then all hands would be busy for three or four hours.”86 Despite the tumultuous journey, with meager rations to sustain them, the two safely arrived in Jacksonville. There Robert boarded for about a week with a Mrs. Donaldson and then took a train headed for Lake City, looking for opportunities to muster in. When the train stopped at a small station, by chance he ran into two fellow Key Westers: Walter Maloney Jr. and, of all people, Henry Mulrennan, the very man who had been exiled from Key West by Union brass that past June.87

Encountering Robert Watson, army veteran and native-born Scot Mulrennan started to formulate a plan to keep the Key West men together. In the meantime, Watson returned to Jacksonville to wait for an opening, possibly on a Confederate steamer. But Mulrennan and Malroney weren’t the only coincidental encounters. At Jacksonville, Robert Watson experienced a shock when he spotted three familiar faces in town: Key West compatriots William Sawyer, Peter Crusoe and Marcus Oliveri. He could hardly believe that his friends did “step on shore for we thought they were in Key West for we were told in Nassau that they had gone back to that place. They had been landed at Cape Florida [the present-day Miami region] and walked and boated it from there to Enterprise and there took a steamer for Jacksonville where I met them.”88

The three adventurers from Key West had made their way through difficult, uncleared terrain, either slogging across sand along the coast or through thickets of saw palmettoes and pines in the dense Florida forests, where they might have caught sight of deer and bears. Fortunately, they had found passage aboard a steamer, mostly likely with sympathetic sailors. Major French’s denial of their passes had only hardened these Key Westers’ resolve to join the Confederacy. It was one thing to risk one’s life when battle started, but Watson, Canfield, Lowe, Oliveri and Sawyer had risked a good deal already.

Reunited with three of his comrades, Robert Watson said goodbye to his other friend, Canfield, who promptly signed up for a Confederate-allied blockade-runner, the ironically named Olive Branch. Watson and the others bided their time while Mulrennan, a natural-born ringleader, set things into motion. Within a short while, a Mr. Smith had contacted him and told him that “Mr. Mulrennan had sent him to try and ship me together with Olivevus [sic] Marcus, Alfred Lowe and Wm. Sawyer in the Coast Guard,” which the resourceful Henry Mulrennan was forming.89 Soon the Key Westers found themselves traveling to Cedar Keys on the Gulf of Mexico to enlist in the Florida Volunteer Coast Guard Company, reporting to Captain Henry Mulrennan. Fellow Key Wester Walter Maloney Jr., son of Union man Walter Maloney Sr., served as his lieutenant. Then Robert Watson had to walk from Clear Water Harbor to Tampa, about thirty-five miles by his reckoning, but at last the company was taking shape. Soon it became like a regular Key West reunion.

Their company of Key West men, along with others from Florida, found themselves stationed at the backwater Point Pinellas on Tampa Bay, just in time for Christmas. On December 24, the newly enlisted coast guardsmen christened a thirty-foot boat named the Mollie Post, as Robert Watson described: “Launched our second boat and had a jolly time of it. Mr. Post requested Mr. Maloney to name her Mollie Post [after his young daughter], which was done. He bought down a lot of whiskey and we launched the boat with Mr. Crusoe and little Mollie Post in her. When the boat was in the water Mr. Crusoe gave us a short but very appropriate speech after which we all took a drink.” On Christmas Day, they toasted to the holiday with eggnog. Despite the celebratory atmosphere, there was a more sober reality. If this collection of Key West friends had set sail during the holidays, it might have taken a day and half at sea, more or less, to reach Key West Harbor and be reunited with their wives, mothers, fathers, sisters and bothers. But Key West may as well have been situated on the moon, as Union forces held the island, while they now camped—as enlisted men—in Confederate Florida.

With three ships—the gaff-rigged sailing sloop Kate Dale, the largest at approximately eighty feet,90 and the more modestly sized Mary Jane and Mollie Post—Mulrennan and the guardsmen patrolled the shore as they scanned the waters for signs of enemy craft.91 Federal ships might create a blockade of a strategically important harbor; the company’s mission was to ensure that Tampa Bay and other surrounding coastal outposts did not suffer a blockade (or capture, as had occurred in Key West). The vessels also assisted in the transport of officers and cannons.92 For the time being, they were somewhat left to their own devices on the Florida coastal frontier. Robert Watson reported them building their own barracks out of palmettoes and then laboriously digging a well “which caved in as soon as it was dug.”93

For a short period, Mulrennan and his men enjoyed relative freedom. One evening, the coast guard recruits gathered around the campfire “playing music, singing, dancing, spinning yarns.” Washing clothes, target practice, drill practice and gathering oysters to supplement their basic fare filled their days. Occasional treats of beer or wine lightened the men’s spirits. At one point, Robert learned that his friend Cyrus Canfield’s ship had been captured by Union forces and Cyrus himself taken prisoner. He even received a letter from his brother, George, who had returned to Key West. The young man’s attitudes toward the world around him gradually emerge in his diary: one day, Robert and the others seized an older gentleman named Pratt, who “was living with a Negro woman that cooked for the officers.” The interracial relationship apparently infuriated the white Key Westers. They threw Pratt bodily off a wharf into the bay and warned that “if he was caught doing the like again that we would give him thirty nine lashes.”94

Besides Watson and his friends who had left on the Lady Brannerman (Sawyer, Crusoe, Alfred Lowe and Oliveri), there were other Key Westers serving in Mulrennan’s volunteer coast guard company: Walter Maloney Jr., Joseph Fagan, Charles H. Berry, John T. Pent, Samuel Morgan, John T. Lowe and the Spaniard Manuel Francisco Diaz. The names of these Key West Confederates all appear in Jefferson Browne’s classic chronicle, Key West: The Old and the New; additional Key Westers appear to have served with Mulrennan in this early coast guard as well, such as John Russell,95 Samuel Young Sawyer,96 Joseph S. Bartlum (son of one of Key West’s finest shipbuilders),97 William D. Curry,98 Benjamin Albury (or Alberry)99 and seventeen-year-old Joseph (or Josephus) Moss.100 A few of the Key Westers had relocated to other Florida settlements before the outbreak of war and joined Mulrennan’s company,101 including the curiously named Augustus Azariah Archer, William Brownell Meares and George Victor Rickards.102 (Just after Robert Watson joined Mulrennan’s coast guard, he wrote wryly in his diary, “Called on Gus Archer, Dicks Mars, John Lowe and some more Key West unfortunates. They were all very glad to see us and treated us like brothers.”103)

In January 1862, on the shore of Point Pinellas, the assembled men adopted a fierce nickname for their company. The new moniker may well have been aimed like a hard slap in the face to Major French, the Union officer who tried to stop them leaving their island home: they were now the “Key West Avengers.”104

Perhaps the islanders had not been able to defend their home against Union seizure and occupation; perhaps, unlike in Savannah or Charleston, they had not been able to enlist in their hometown, where they might have been sent off to war with parades and music as they waved goodbye in uniforms that their mothers and sisters had sewn by hand. But here, farther north on Florida’s coast, they were primed to avenge what these Confederate enlistees saw as a great calamity: Union control of the Florida Keys.

Key Wester John T. Lowe served in Mulrennan’s volunteer Florida Coast Guard. Courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

The Confederacy needed men and organization, and the Key West Avengers were not permitted to monitor Florida’s central Gulf of Mexico in their three craft, the Kate Dale, Mary Jane and Mollie Post, for long. In late April, “the company known as the Key West Avengers, and commanded by Capt. Henry Mulrenan, at Tampa Bay” was specifically mentioned in a letter to Florida governor John Milton as one of the companies “ordered to be mustered into Confederate service.”105

Captain Mulrennan and his fellow officer, Second Lieutenant (later Captain) Smith, were charged with leading the men as they were absorbed into Company K in the 7th Florida Infantry. The days of patrolling the Gulf of Mexico ended; the short-lived Key West Avengers would be dispersed, and many of the Key Westers would now see intense action.

Yet the Key Westers’ appointment into the 7th Florida Infantry did not sit well with them: they were sailors, wreckers and ship carpenters and felt it would be a waste to have them trudging through the countryside when the Confederate navy faced fierce sea battles, requiring special nautical skills that they possessed in abundance. The men gathered together, and Peter Crusoe composed a petition to the secretary of the Confederate navy that asked they might be mustered into the navy instead. It just so happened that the secretary was a Key West man himself, Stephen Mallory. (As connections went, this was a fine one.) Twenty-five men, referring to themselves as “Citizens of Key West, Fla.,” respectfully signed a petition on May 1, 1862:

They are sincerely anxious to render good and efficient service to their country and are satisfied that the Army is not the proper place for them, that they have been informed that Seamen in the Army can be transferred to the Navy, and therefore make this their application, and pray to be transferred to a Gun Boat or other vessel of war where they may have a chance to meet the enemy and strike for their Country’s cause.106

To a degree, the petition persuaded Mallory. Charles Berry, Samuel Morgan, John Sands and others went into the navy. (Robert Watson, whose skill had helped his leaky transport stay afloat from the Bahamas to Jacksonville, was not transferred to the navy until 1864.) Certain Key West Avengers could remain at sea but now aboard other ships—sometimes with a familiar face, but in other cases mixed in with a crew of strangers far from home.

Captain Smith and Lieutenant Maloney would lead the Key Westers into battle on land; here Henry Mulrennan momentarily disappears from the record again. After all his efforts to gather his island compadres together on the Gulf Coast of Florida, the Scottish shopkeeper and war veteran did not join Robert Watson and Company K on their long march to Knoxville, Tennessee. Instead, Mulrennan sailed back to waters he knew so well. Robert Watson heard the news that “Mulrennan, Coste, and Marcus have run the blockade to Havana in two smacks [fishing boats]. They left here on the 8th of January and I have heard that they arrived safe in Havana.”107

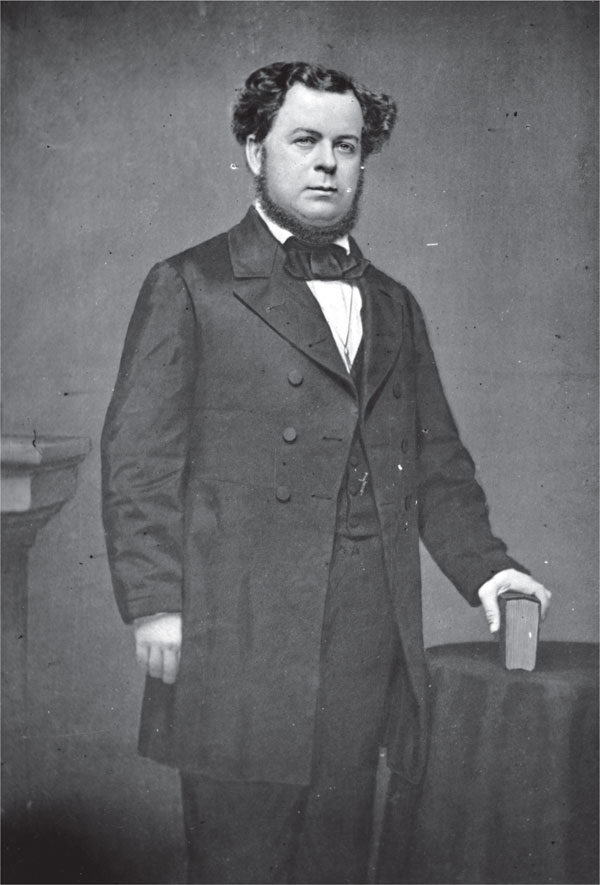

Key Wester Stephen Mallory became secretary of the Confederate navy. Courtesy of the Monroe County Public Library, Key West.

Just as quickly as the company formed, the Avengers vanished with nary a trace, swallowed up by the Confederate war machine. For sure, some of the men remained together in the Company K, 7th Florida Infantry, but it would never be the same. What began like a chapter from a boy’s adventure story, with stowing away and singing by the campfire, morphed into a difficult war. Watson’s diary describes illness, near starvation and scenes of barely contained chaos. For him at least, there was very little glory.

As we look back at those Key West men who went to such great lengths to fight for the Confederacy, one of the most surprising commonalities is how many of them were foreign-born. Mulrennan hailed from chilly Scotland; Crusoe was born in Gibraltar and Marcus Oliveri in Genoa, Italy. Yet a majority of the Key Westers serving in the Key West Avengers hailed from the Bahamas.108 It initially can strike one as strange that these immigrants from nearby islands risked their lives for the South.

Both white and black Bahamians settled in the Florida Keys from the 1820s onward and helped to mold the population’s essential character. After Lincoln was elected in 1860, a number of white Bahamians showed a strong affinity for the South. They may have had varying reasons to pledge their loyalty to the Confederacy, including issues of states’ rights and taxation. And then there is the issue of slavery, an institution that had already been abolished in the Bahamas. How did the white Conchs who enlisted with the Confederacy feel about slavery, and did it factor into their decision to enlist?

In 1834, the formal abolition of slavery throughout the British West Indies took place, although an “apprenticeship” system (essentially slavery by another name) lasted until 1838. It would be a mistake, however, to imagine that white Bahamians and black Bahamians responded to this news with similar emotions. For enslaved people, this turn of events meant freedom and was a cause for great celebration. For most West Indian whites— including those in the Bahamas—abolition meant a sometimes drastic change to their economies and, perhaps more compellingly, a fundamental upheaval in the social order. Decades after abolition, even poor whites in the Bahamas “despite their poverty, despised nonwhites.”109 In fact, “well into the twentieth century the white [Bahamian] elite controlled the political, social, and economic life of the colony,”110 and “the system of racial discrimination inherited from the institution of enslavement persisted into the 1960s.”111 As Bahamian scholar Gail Saunders has documented, for well over a century after abolition, racial tensions in the Bahamas mirrored “the inflexible color line of the United States.”112

Emancipation in the Bahamas had not resulted in whites learning to accept blacks as fellow citizens or equals; on the contrary, whites’ contempt for blacks remained and, in some cases, perhaps intensified, as their resentment of these now-emancipated people of color grew. (This development would be echoed in the post–Civil War South, when white Southern antipathy toward blacks increased.) White Bahamians who immigrated to the Florida Keys in the antebellum period would not have harbored any special sympathy toward blacks or necessarily supported black emancipation; some may have found comfort in living in a new land where the old social order of a slave society was still entrenched. Even in the Bahamas’ colonial motherland, Great Britain, there was plenty of support for the Confederacy. In reality, “substantial sections of Britain’s business elite were working with impunity to help the slave-owning southern states win the Civil War—despite the fact that Britain was officially neutral and had outlawed slavery almost 30 years earlier.”113

As incredible as it may seem to us today, in the English-speaking world outside the South, there were many who either tolerated or supported the old order and loathed the idea of social change. Robert Watson, born on Ragged Island in the Bahamas, had arrived in Key West with his parents in 1847 to find a place where certain leading citizens owned slaves as a matter of course. Up until 1838, black enslavement had been the way of things in his homeland as well. On Ragged Island, slaves had tended to the profitable salt ponds.114 Meanwhile, at least 4 of Watson’s Key West Avenger comrades had been born on tiny Green Turtle Cay, where, as of 1834, white Bahamians—including those with last names Russell, Curry, Sawyer and Lowe—owned 241 black men, women and children.115 Having witnessed relatives and neighbors lose valuable “property” due to emancipation in the Bahamas, white Conchs may have felt determined not to allow the same thing happen in Florida.

In the published version of his diary, however, Watson does not comment on slavery, although his hatred of Yankees and “Lincolnites” is clear, and he particularly objected to being housed with “Negro soldiers” when the war was over. (Most white Union troops would have felt the same.) Did Watson, Alfred Lowe and the other Conchs who mustered into the CSA and the CSN support slavery, or were there other motivating factors? That history still waits to be uncovered. One fact is certain: Although there may have been white Bahamians in the Florida Keys who felt pro-Union, at the outbreak of the Civil War it appears that a number of them allied themselves politically, culturally and emotionally with the Confederate States of America.

Of course, the short-lived Key West Avengers were not the only Confederates to emerge from the Florida Keys. Some of these other stories, such as that of merchant Asa Tift, are better known; one also cannot overlook the pro-Union citizens who found the idea of secession illegal and traitorous. Their stories are hardly hidden history either: Walter Maloney Sr., who supported the Union from the beginning, and Judge William Marvin, who punished blockade-runners in court, are just two examples. Many Key Westers eventually signed an oath of allegiance to the United States, some because they had always thought secession wrong and others because they realized which way the winds of war were blowing. Even those with pro-Union leanings often had a deep prejudice about their black neighbors, however. A Northern colored regiment eventually served in Key West and found its welcome less than warm. The complex Civil War history of the Florida Keys could fill a long volume.116

Walter Maloney Sr. was a staunch pro-Union man; his son fought on behalf of the Confederacy. Courtesy of the Monroe County Public Library, Key West.

In the end, what exactly happened to those tenacious Keys men who risked their lives for a Lost Cause? Charles Berry died in 1863 in the explosion of the CSS Chattahochee. William Sawyer died early in his service, in 1863, and was buried in Tennessee. William D. Curry contracted malaria during his service and stated on his Confederate pension application in 1886 that he had never recovered from the disease. Peter Crusoe’s career as a Confederate did not impede his standing in Key West: after the war, he resumed his position as clerk of the circuit court. Walter Maloney Jr. returned to his island city, reconciled with his pro-Union father and served a term as mayor. Manuel Diaz returned to Key West, married a woman named Ascunsion and lived until 1910. Despite being shot in the hand, John Pent also survived the war and settled back in Key West, where he wed Elizabeth Bowe; they would die in 1919 within a month of each other. Another man who returned to Key West safely was Joseph Bartlum, who eventually passed away in his sixties. Key Westers Alfred Lowe and John Thomas Lowe participated in the dramatic scuttling of the CSS Savannah, before General Sherman seized that eponymous Southern city; Alfred lived in Key West until his death in 1921, while John settled on the Florida Gulf Coast and died not far from where the Avengers first camped. Henry Mulrennan, Rebel firebrand and later Confederate blockade-runner, lived through the Civil War and went on to serve as Key West mayor for two years. Today, visitors to the Key West cemetery will find a Confederate marker atop his grave.

Diarist and onetime stowaway Robert Watson was captured by Union troops in Virginia, one day before Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. As a prisoner in Washington, D.C., he recorded, “I don’t want to take the Oath [of Allegiance to the United States] but if they send me to prison I will take it for I am satisfied that the South has gone up the spout and it is of no use for me to linger for a long time in prison for no purpose.”117 Having written that, Watson nonetheless refused to sign the oath yet still managed to get paroled and returned to Key West. His diary, published in the twenty-first century, attests to the mundane horrors of war, including near starvation and disease. In one typical passage, he wrote, “Nothing to eat but we are all well supplied with lice.” Another evening, he recorded, “Mud ankle deep and not a wink of sleep. Stopped raining at midnight when we stripped off and dried our clothes by the fire. All hands as hungry as wolves and nothing to eat.” The Key West Avengers’ grand adventure, which had begun in high spirits, turned into a grim, relentless slog.

Confederate veteran Robert Watson built this house at 522 Simonton Street in about 1869. Courtesy of the Monroe County Public Library, Key West.

Henry Mulrennan’s grave site in the Key West Cemetery. Photograph by Laura Albritton.

As Watson, Lowe and others trickled back to their homes within a once again united United States, more than 600,000 men lay dead. Almost 4 million men, women and children of color were now freed of their shackles, and an assassin had murdered one of the greatest American presidents to ever live. The world that some had hoped to preserve in amber had changed. After all the tragedy, the deaths, the strange adventures and sleeping out under unfamiliar skies far from home, there was nothing left to avenge. Those who survived returned to their lives and carried on.