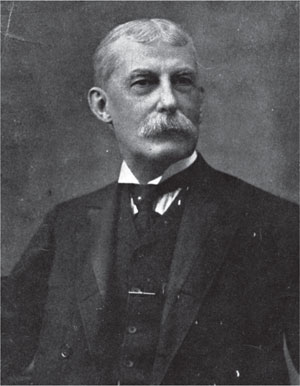

Standard Oil millionaire Henry Flagler believed that the Overseas Railroad would become a reality. Courtesy of the Monroe County Public Library, Key West.

CHAPTER 5

THE GREAT KEY WEST EXTENSION SCARE

It sounds like the premise for a fantastical novel: A millionaire dreams up the scheme for a train that travels clear across far-flung islands, chugging away on tracks laid over man-made fill and soaring high above the aqua-blue ocean on bridges that span miles. The millionaire was, of course, Standard Oil co-founder Henry Morrison Flagler, and the islands in question were the stunningly tropical yet mostly undeveloped Florida Keys, at the very southernmost latitudes of the United States. For hundreds of years, these “keys”—rocky outposts dotted with palms and red-barked gumbo limbo trees—had largely been the dominion of wild seabirds; later, Indian tribal peoples lived here off the abundance of the sea. Then, in the nineteenth century, Key West blossomed into a wealthy frontier town, while small settlements in the Middle Keys and on Indian Key sprang up for a time before fading away.

All that would change with the coming of Henry Flagler’s trains—that is, if his people could bring this “Eighth Wonder of the World” to actualization. It was the early twentieth century, an era of grand ambition and breakneck technological innovation. Although some expressed doubt that a railroad running from the southern Florida mainland clear across the islands to Key West could be built, Flagler had confidence that it would.

To accomplish such a seemingly impossible feat, he would need equipment, steel, concrete, fill, workers and brilliant engineers. In the process of building the railroad, Flagler’s chief engineer, Joseph Meredith, would literally work himself to death, leaving his principal assistant engineer, William Krome, to see the project through to its completion. But at one point during the long saga of the Overseas Railroad, the scheme would falter. In fact, for two precarious years during its construction, the future of Key West’s railroad connection fell into doubt. It was a battle largely hidden from public view, pitting two indomitable forces against each other. Had one side not prevailed, the railroad might have terminated in the Middle Keys, with Key West as isolated as ever.

Standard Oil millionaire Henry Flagler believed that the Overseas Railroad would become a reality. Courtesy of the Monroe County Public Library, Key West.

The technically demanding task of connecting the southeastern Florida mainland with the Florida Keys, carried out under intense sun amid swarms of mosquitoes, started in 1905, with the first stretch running from Florida City to Jewfish Creek. People came to call the project the “Overseas Railroad,” but its official title was more of a mouthful: the Florida East Coast Railway’s Key West Extension. Industrialist Henry Flagler had already run the Florida East Coast Railway all the way down the state to Miami. He did not intend on furthering the railroad with a link to the Florida Keys out of the goodness of his heart: his goal centered on using his Pacific & Occidental steamers, along with railroad ferries, to run between Havana and Key West; tropical produce from Cuba could be whisked all the way up America’s East Coast by rail, while tourists in search of warm weather could ride the rails south to Flagler’s hotels along the coast of Florida (and, ultimately, in Key West). As historian Tom Hambright noted, “Miami wasn’t a shipping port at the time. The only real natural port in those days was Key West. In 1900, it was Florida’s largest city, a bustling port alive with the cigar industry, fishing and sponging. So the impetus for building an overseas railroad was that Henry Flagler needed a port.”128 Yet the implications of a Key West terminal and rail link went well beyond Flagler’s own company interests and might have extended to American trade more generally. In early 1907, the Morning News predicted that “with these harbor facilities, Key West will almost immediately rank with New Orleans, Mobile, and Galveston as a commercial port.”

Two years into construction, in 1907, publicity surrounding the FEC’s Key West Extension had ballooned until it was one of the most famous construction endeavors in the United States. The sheer audaciousness of the undertaking fascinated the public. But not everyone admired it—William Randolph Hearst’s newspapers attacked “Flagler’s Folly.” Yet despite its detractors, the work moved ahead steadily. Obstacles that surfaced were overcome with money, skill, cunning or some combination of the three. When a new challenge arose over land usage in Key West, the solution at first seemed straightforward.

Today, Key West has a land area of only 5.27 square miles, but in 1907, the island was even smaller. Obtaining adequate land for the sizeable Key West terminus (final station) and docks remained a major headache for Flagler and his senior staff. And so, Flagler decided with a typically American “can do” attitude to solve the land problem simply: they would create more land. In April, the St. Louis Globe Democrat reported on “the vast expense of the improvements at Key West, where it is proposed to fill in 174 acres of land now under water” in order to “build extensive docks and terminals, as well as dry docks and wharves, each 800 feet long and 100 feet wide.”129

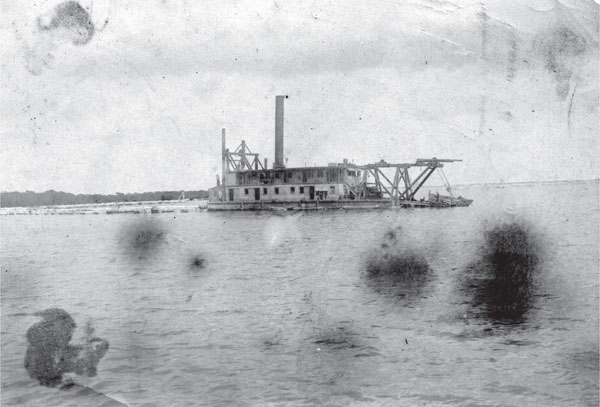

While the railroad construction continued farther north in the Middle Keys, particularly with the Knight’s Key Dock (an offshore railroad “terminus” or station out one and a quarter miles into the ocean), the project at Key West got underway. The FEC opened up a Key West office, and Howard Trumbo of the Trumbo American Dredging Company directed the huge dredging operation. On October 23, 1906, a dredge called the George Allen set to work, bringing forth matter from the ocean floor to create the property that Henry Flagler needed to complete his vision. On November 10, another dredge named the Grampus joined it.130 Things were looking up in Key West. The only serious trouble bedeviling the FEC at that moment was a shortage of workers.

Knight’s Key Dock extended to a location with water deep enough for steamships. Courtesy of the Monroe County Public Library, Key West.

This photograph shows the George Allen, one of the dredges Howard Trumbo directed off Key West. Courtesy of the Monroe County Public Library, Key West.

The FEC’s construction evaluation reports from 1907 tell the story in numbers: in June of that same year, 2,940 men labored on the project. In the Upper and Middle Florida Keys, they built bridges, laid track and dredged for marine marl.131 Engineering and accounting staff worked in the FEC offices at Marathon, while a much smaller staff manned the FEC office on Front Street in Key West. Assistant Principal Engineer William Krome kept scrapbooks in which he pasted newspaper articles recording the railway’s progress. Krome—a slight, serious-looking man whose staid, buttoned-up appearance belied his tenacity and engineering brilliance—kept one short notice from July 10, 1907: “Mr. H.M. Flagler is expected the latter part of the week to view extension work.” The millionaire with the bristly white mustache planned to travel down the east coast of Florida to make a decision about the bridge at Bahia Honda. It seemed that nothing could interfere with the progress of the Overseas Railroad.

Meanwhile, in Key West, the George Allen dug up 55,000 cubic yards of fill from July 1 to July 13, while the Grampus dredged 1,500 cubic yards of rock in that same period.132 The first indication that something with the FEC Railway’s extension had gone amiss appears in Krome’s scrapbook in a small, innocent-looking article from the Key West Citizen dated July 15: “Only an Incident: Stoppage of Railroad Work Only Affects Dredges.” The newspaper account turned out to be overly optimistic.

Two days later, another report emerged that the U.S. War Department itself had caused the stoppage of the railroad’s work. The cause? Allegedly, the War Department and naval authorities halted work “because various channels have been blocked by trestles and viaducts.” This explanation may well have struck readers as vague and not terribly convincing. Then, news for Key West’s terminal grew worse: a telegram arrived from Howard Trumbo, announcing that both dredges would be “out of commission for several months.” The Key West Citizen, in a nervous-sounding piece from July 17, related that “[n]o confirmation or denial of the report would be made by Mr. Wilson, in charge of the company’s office here today, but it is safe to assume that there is something to the rumor.” One day later, the rumor became a concrete reality with an article titled “A Serious Situation: All Work This Side of Knight’s Key Suspended.”133

To say that this news threw many Key Westers into a state of worry would be an understatement. The railroad had become the object of many hopes and dreams, not simply Flagler’s. Merchants, housewives, laborers and manufacturers all could benefit in different ways, both large and small, from a rail link with the mainland. Living on a small island located about 150 miles from the American mainland and 90 miles from Havana, many Key Westers perceived their economic progress in the early twentieth century as hampered by its isolation. Henry Flagler’s train was destined to be the single most transformative event in the Keys, particularly in Key West, since Spain ceded Florida to the United States—if only the second half of the railroad could be built.

The public did not have to wait long for the U.S. Navy’s official reply. In a July 19 Citizen article headlined “The Navy’s Side,” Commodore Beehler, commandant of the naval station at Key West, strongly argued their points. He claimed that Flagler and the FEC had first agreed to sign a contract stating they would eventually replace any fill they dredged at Fleming Key and then reneged. With no contract, the FEC had no right to proceed. Among the most damning was this assertion:

Last May, the railroad company, without authority, deliberately began to take material from the U.S. Reservation at Fleming Key. This is Government property and could not be given away by anyone, except by an Act of Congress. No person, not even the Secretary of the Navy, could give Government property to the railroad or anyone without the authority of the people thru Congress.

The case laid out by the commodore hinged on the notion that the even the sea bottom adjacent to Fleming Key (just north of what is today Trumbo Point) belonged to the United States government. On one hand, one can understand why Flagler and his FEC engineers had not come to the same conclusion: perhaps as far as they were concerned, this material was simply muck, sitting there without purpose in the open ocean. On the other hand, Flagler may very well have believed that the dredging project trespassed onto the navy’s territory and blithely ignored this inconvenient truth. He must have imagined, after all, that the Overseas Railroad would benefit everyone in Key West, particularly the military. Perhaps the thought that the navy might object seemed inconceivable.

We can judge Flagler’s response to this broadside by what happened next. On July 22, 1907, the company posted a notice that “No More Workers Are Needed.”134 Reports declared that all work camps south of the Middle Keys would be relocated to Knight’s Key or farther north. A week later, on July 31, top FEC brass—including Joseph R. Parrott, R.T. Goff and a Mr. Beamis—traveled from St. Augustine and Palm Beach to “assist in reduction of the force,” a newspaper reported. As far as Key West was concerned, the news grew even more serious. On August 11, John E. Lummus, who handled the supply system for the railway company, removed $10,000 worth of commissary supplies from Key West and transported them to the terminal dock at Miami.135 The company also relocated steamers to Miami as work south of Knight’s Key wrapped up.

One newspaper reported that Chief Engineer Meredith had sent a telegram calling a halt to all work on the Key West end of the line. The writer pulled no punches in laying blame: “The reason assigned for this action…is that Mr. Flagler has been greatly annoyed and hampered in his great work by obstructions placed in his way by the government, especially the Navy Department.”136 The same article ended on a note of anxiety: “It is sincerely hoped that the trouble may be speedily adjusted, as Key West’s future is at stake.”

Florida East Coast Railway company officials remained quiet. One rumor emerged that the railroad might stop midway along the island chain, with service onward to Key West only by ship. As far as we know, Flagler and his representatives neither denied nor confirmed the stories, which only fueled speculation and, in some cases, wild rumor. In fact, one paper reported that Flagler was dying of the “grippe” (influenza). Another newspaper, with the dramatic headline “The Coils that Are Crushing H.M. Flagler,” asserted that the great man’s health was “shattered by the collapse of his costly Key West railroad enterprise.” (An illustration of a giant cobra poised to strike a cartoon Flagler added to the sense of impending doom.) “Friendly,” pro-Flagler newspapers countered these stories as hearsay, with one paper retorting that the millionaire remained in the “best of health.”137 Meanwhile, news from the southernmost key did not improve. By November, a South Florida paper reported that “the fixtures and supplies of the extension office at Key West have been ordered packed and shipped to this city [Miami] and the office there closed for the present.”

The Florida East Coast Railway’s first office in Key West was on Front Street. Courtesy of the Monroe County Public Library, Key West.

From Key West’s earliest days as an American outpost, the U.S. Navy had commanded considerable—and, at certain points in history, absolute— authority there. In the case of a territorial dispute, the naval commodore naturally expected the FEC Railway to fall in line. Yet what the navy failed to reckon with was the power and shrewdness of a man like Henry Flagler. Flagler might have launched an open dispute with the navy over the Fleming Island dredging, or perhaps a public relations campaign, but he did not. Flagler and the FEC allowed their actions to speak for themselves. It was one thing to send away the two dredges but another to strip the Key West office bare of its furniture and light fixtures. Although the thought of eliminating the Key West terminus from his plans must have been devastating to Flagler, outwardly, his company behaved coolly. In response to War Department mandates, the plan for the Overseas Railroad seemed to have definitively changed. By the following summer, in July 1908, the FEC workforce had fallen from 2,940 to 795 men, a reduction of nearly 70 percent.138

In May 1908, ten months after the dredge work stopped, the Key West Citizen announced that “Mr. Flagler Sends Regrets to Key West.” The paper told readers that “Mr. H.M. Flagler writes that his inability to visit Key West this season has caused him much regret, but he expects to make up for his loss next year by paying frequent visits to our city.” One cannot help but hear a note of desperation in the next sentence: “There is no place in Florida where he will find such genuine friendship.” In case there was any doubt about Key West’s attitude toward the industrialist, the writer added, “We sincerely hope that his health will remain good during the summer so that he may give his great enterprise here a great deal of his time next winter.” The disappointment of the community about the possibly canceled project is obvious.

For about two years, no one spotted the dredges George Allen or Grampus working off Key West’s northern shore. The island city saw its hopes of connection by rail to the rest of America evaporating. To compound the bad news, Principal Assistant Engineer William Krome resigned from the project in October 1908.139 Instead, he would oversee his groves in Homestead. The news grew even more dire when Chief Engineer Joseph Meredith died unexpectedly in April 1909.

It was quite a blow when Flagler’s chosen man, Meredith, died of overwork and complications from diabetes. Fortunately, Krome agreed to come back, now as chief engineer in charge of the whole works, with his headquarters at Marathon. The railway company even presented him with a loving cup, a kind of trophy, to recognize his service. In this case, it wasn’t for a job completed, but rather a job that still had years left to go. But would the railroad still stop in the middle of the Keys or go all the way? That was the looming question that caused so much anxiety, especially in Key West.

This FEC maps depicts “Land made by Mr. Flagler.” Courtesy of the Monroe County Public Library, Key West.

Then, on September 11, 1909, a newspaper announced, “Work Resumed on Trumbo Island.”140 And just like that, the public was informed that the Overseas Railroad, stretching from the Florida mainland across the scattered islands, would indeed make its way to Key West. Somehow or another, Flagler had gotten his way. The U.S. Navy raised no more objections. In fact, what should have been clear from the beginning was that the War Department needed his train system much more than the submerged fill.141

At last, the FEC station at Key West’s Trumbo Point was completed. Courtesy of the Monroe County Public Library, Key West.

The mystery remains: what exactly happened behind the scenes? Were there feverish negotiations between the FEC and the U.S. government? Were strings pulled at the very highest levels in Washington? While the newspaper clippings in William Krome’s scrapbooks tell us that the stoppage did occur and that the FEC appeared to change its goal of reaching Key West, some of this history is still hidden from view. We can surmise that some intervention took place, but how precisely the standoff was resolved in Flagler’s favor still remains a mystery.

A map drawn after the railroad’s completion shows the FEC’s Key West terminus, along with the words “Land Made by Mr. Flagler,” as though the millionaire had crafted the land with his own two hands or perhaps conjured it out of the ether like a genie. While no magic brought about the completion of the FEC’s Key West Extension, one can only speculate about the particular brand of business genius that Henry Flagler used to make it happen. One final irony: years later, the U.S. Navy purchased the “Land Made by Mr. Flagler” from the FEC Railway company to use as the Trumbo Point Naval Air Station.