Hops, Malt, Yeast, Water, and Magic

The short answer to that question is hops, malted barley (or other fermentable cereal), water, and yeast. Combine those four ingredients without any clue how to brew, leave them out, and one of an infinite number of random outcomes would be the inadvertent production of beer.

Life would be extremely boring if it were that simple. We wouldn’t have the hundreds of styles we enjoy today without the exponential number of possible proportional combinations of those items, nor would we have the hundreds more that are possible when we let in a host of other ingredients. Everyone talks about hops and how they like their beers hoppy (or not), but the majority of people in America don’t know or aren’t quite sure what in the world hops are.

The hop might be the most popular component of beer these days, but among the four core ingredients, it was the last to join the group. Brewers started putting them in their products only about seven hundred or eight hundred years ago. Sounds like a long time ago, but, in the grand scheme of things, when a beverage is around 7,000 years old, it’s like it just happened last week.

When people talk about hops, what they’re really referring to is the flower of the hop plant, also known as humulus lupulus among scientists. These flowers look like tiny green pinecones. Within each one is a yellowish area that’s home to the lupulin glands, which contain the alpha acids that impart the bitterness and essential oils responsible for beer’s flavor and aroma. Hops have another benefit: they’re a natural preservative and extend the beer’s life.

More often than not, the hops used in modern beer production are in pellet form. The hop flowers are dried and compressed into tiny pellets that could pass for aquatic turtle food. The lupulin components are more concentrated in this form, meaning fewer are required to brew beer, although the processing does cause the hops to lose some of their aromatic quality. Brewers sometimes employ whole-leaf hops, which are dried hop flowers that have been baled together like hay. Since there’s more of the actual plant left in whole-leaf form, brewers need to use a much greater quantity of them than they would if they were using pellet hops. Some producers may use a combination of pellet and whole-leaf forms.

Then there’s the wet-hop phenomenon, which has become a popular way to amp up the complex flavor and aroma that the little flowers provide. Wet hopping entails adding fresh, whole hop cones, taken right off of the vine, into the brew. Pellets are still primarily used, but the fresh cones give beer an intensity it wouldn’t otherwise have from pellets alone.

How about a little sugar to balance out this talk of bitterness? That’s where the grain comes in. Malted barley is the grain of choice for beer, though plenty of other cereals are commonly used. The malt process is required to unlock the enzymes that convert starches into fermentable sugars.

To malt barley or other grains, the maltster must soak those cereals in water and allow them to germinate. When they begin to sprout, the maltster halts the germination process and then air-dries the grain. When that process is complete, drying continues in a kiln. The amount of time the malt spends in the kiln depends on the desired color and degree of flavor. On the light end of the spectrum, pale malts have very little roast character, while dark, chocolate malts have fresh-roasted coffee (and, of course, chocolate) characteristics.

Wheat has become one of the more popular non-barley grains to use in brewing. Hefeweizens, Belgian Witbier, Berliner Weisse, and other refreshing brews all use wheat in their mash bills, although the wheat is usually combined in varying proportions with barley malt. A classic hefeweizen may have a wheat-to-barley ratio somewhere between 50:50 and 70:30.

Malt plays just as crucial of a role in beer’s flavor as hops do; the malt sweetness balances the hop bitterness. It also gives the brew a lot of its body.

But malt’s most important job is to provide food for the yeast. And this is where beer comes alive. When malt and hops are boiled together in water, the resulting liquid is wort, which is an alcohol-free, uncarbonated precursor to beer that tastes vaguely like tea. It’s only when the brewer adds yeast that the true magic happens.

In order to fulfill it’s role in the beer-making process, yeast requires generous helpings of fermentable sugar. To put it simply, yeast “eats” sugar and excretes alcohol as a byproduct. When fermentation concludes, beer, for all intents and purposes, is the resulting liquid. However, it’s going to be unpleasantly flat because it’s yet to be carbonated. There are two ways to add carbonation: forced and natural. Forced is just as it sounds: CO2 is added to the liquid, giving it its bubbles. It’s the more economical method because it’s much faster than naturally carbonating the brew. However, there really is no substitute for a naturally carbonated beer.

To go au natural, some sugar is added to the container holding the still beer—it goes right into the bottle if it’s a bottle-conditioned brew—to activate the yeast. After about two weeks, here be bubbles!

And, voila! Beer has happened!

That’s the Cliffnotes version. There are so many varieties of hops—with new species being cultivated seemingly every week—a vast array of malts, and a veritable kingdom of yeast species, that it’s impossible to do little more than scratch the surface in these pages. But a brief snapshot certainly helps.

Hops

Cascade: When people talk about quintessentially American hop character, it’s very likely they’re referring to the Cascade type. Floral, spicy, and very citrusy, Cascade is a hop that screams out to be noticed.

Fuggle: The go-to English hop had its heyday in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It initially grew wild in the hop mecca that is East Kent, until it was domesticated and commercialized in the 1870s by its namesake, Richard Fuggle. Today these faintly fruity flowers are used for aromatic purposes.

Golding: Another of the big English exports, Goldings also originated in Kent. The crème de la crème are East Kent Goldings; if they’re grown anywhere else in Kent, they must be called simply Kent. Outside of Kent, they’re just Goldings.

Hallertau: One of the noble German hop varieties, Hallertau has a mild, spicy, and floral aroma and therefore is ideal as an aroma hop. It’s a bit of a Bavarian legend, as it was the predominant hop used in the region for some time.

Mosaic: Mosaic is the progeny of Simcoe (see below). This hop is characterized by its earthy, tropical, citrusy, and piney expressions and is relatively new to the party. It’s primarily used as an aroma hop, most frequently in India pale ales.

Nugget: Nugget is an American hop variety first released in the early 1980s and has become one of the most widely grown hops in the state of Oregon. It boasts some fairly powerful bitterness thanks to its high alpha acidity. It has an herbal, earthy aroma and is used primarily for bittering purposes.

Saaz: Born in Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic), this hop is the preferred variety for flavoring the classic Czech-style pilsner (the one by which all global variations on the style should be measured). This hop is more aromatic than it is bitter, and it’s quite pleasing to the nose and the palate.

Simcoe: A popular component of hop-forward brews like pale ales and India pale ales, the Simcoe variety suggest pine forests and passionfruit.

Sorachi Ace: Japan’s contribution to hops, Sorachi Ace has become a favorite of brewers worldwide for its intense bitterness, spice, and lemon-like qualities. It’s such an iconoclastic hop that the Brooklyn Brewery named a saison after it.

Tettnanger: Named for the Tettnang region of Germany from which it hails, Tettnangers are somewhat fruity and spicy and are, along with Hallertau, one of the German noble hop varieties. Alpha acids are on the low side in Tettnangers, and they are commonly used as aroma hops in a lot of the big, classic German beer styles like pilsners, Munich Helles and Kölsch.

Hops, of course, are only part of the story. Good beers require healthy malt backbones, and styles of barley malt are just as bountiful as hop varieties. However, malt character is more about the human interface, the level of kilning or roasting, rather than variations in species. To understand malts, it’s important to distinguish between base malts and specialty malts. Base malts are going to contribute most of the starches that will be converted to fermentable sugars. Therefore, they’re the ones that will be used in the largest quantity in the brew. On the other hand, specialty malts are used to impart certain desired elements—such as flavor, color, and mouthfeel—that the beer won’t get from the base malts alone.

Hop vines.

Base Malts

2-Row Malt and 6-Row Malt

Two-row and 6-row malt are so named for the way the barley grows on the stalk; with the former, the kernels are arranged in two rows, while the latter’s kernals grow in six rows around the stalk. Because of the smaller number of rows, 2-row malt kernels are typically larger than 6-row kernels. Six-row tends to have more protein content, while 2-row has more carbohydrate composition. Two-row usually results in a maltier flavor, while six-row tilts toward a grainier flavor. Six-row grows only in the United States.

The two most commonly used 2-row malts are the British and US variations. The main difference between the two is that the former tends to be a bit darker and produces slightly fuller-bodied beer. The British variety also is known to impart “bready” elements to the finished brew.

It has the potential to get confusing when we talk about the further varieties within 2-row:

Maris Otter is on the darker, nuttier side of British 2-row malts.

Golden Promise, a less commonly used British 2-row, frequently produces a sweeter end product.

Pilsen or Pilsner Malt

Most standard lagers will use the very pale pilsner malt. In the world of base malts, they’re kind of the wallflowers. They show up, but they stay in the background, letting the other malts get all the attention. That’s especially beneficial if the brewer is trying to achieve a certain flavor, color, or body with specialty malts; pilsner malt won’t stand in the way. There are, of course, many geographic variations of the standard pilsner malt—Belgian, German, and American, to name a few.

Pale Ale Malt

A touch darker than pilsner malts, pale ale malts are the typical base malts of English-style beers and their many descendants (American pales, IPAs, and the like).

Munich Malt

Taking its name from the Bavarian city, Munich malt imparts some sweet characteristics as well as a bit of an amberish hue.

Jars of malted barley.

Wheat Malt

As its name suggests, wheat malt is derived from a grain other than barley. It’s the core element of wheat beers, whether they are Belgian wits, Bavarian hefeweizens, or the various other wheat-centric styles.

Vienna Malt

One of the more notable characteristics of the malt named for the Austrian city is that it gives beer a bit of an orangish complexion. Vienna malt is fairly biscuity in flavor and is frequently the base in Vienna lagers (naturally) and other amber-red brews like Märzen. It’s somewhat similar in color to Munich malt but slightly less dark.

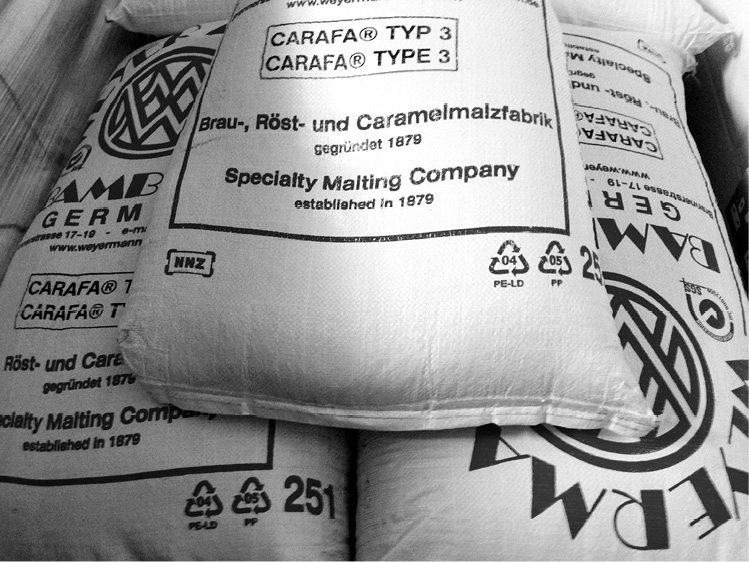

Sacks of malt from Bamberg, Germany’s Weyermann.

Specialty Malts

Speciality malts account for only about 10 to 20 percent of the overall grain bill, but that’s enough for them to contribute various desired flavor and aroma characteristics. Here’s a snapshot of some of the most commonly use specialty malts.

Caramel and Crystal Malt

Caramel and crystal are terms that are often used interchangeably; the former is the more descriptive of the two, as it relates to the caramel-like flavor these types of grains impart to the beer. Maltsters achieve such characteristics by applying a much different process to the grains than they would to the common base malts. For standard malts, the maltsters heat the grain in a dry kiln, but for caramel and crystal malts, they stew what’s called green malt in a very moist oven. Putting the malt in the water is akin to putting it in a mash tun, where the grain’s starch is converted to fermentable sugar. But this process doesn’t actually produce wort since one critical step is missing: the milling/crushing process. What actually happens is that the grain crystallizes when cooled, resembling sugar crystals. It’s then dried with heat.

Like many other malt classifications, caramel malts have various sub-categories:

Cara-pils is light in color and adds a bit of sweetness to beer. It’s typically used to foster better head retention.

Cara-Vienne is darker (as the beer style hinted at in the second part of the name suggests) and adds body to the brew.

Cara-Munich also adds body and a richer mouthfeel and is popular in a lot of more robust German styles like bocks and Oktoberfest/Märzens.

Biscuit Malt

The malted grain whose name sounds like a cookie is lightly roasted and notable for its toasted bread, cracker-like characteristics. It’s a common malt in Belgium.

Chocolate Malt

Yes, chocolate malt is brown in color and, no, there’s no actual chocolate involved. This malt’s primarily roles are to darken beer and impart lots of roasty, chocolate-like notes. Stouts and porters get their defining hue and flavor characteristics from chocolate malt.

Black Patent Malt

Like chocolate malt, black patent malt is extremely dark, but it doesn’t have many of the flavor characteristics of the former. Use of this malt is ideal when color, not flavor, is the objective.

Roasted Barley

What sets this dark brown grain apart from the previous two is that it’s not malted before it’s kilned—therefore it is not actually a malt. It’s a very coffee-like component of stouts.

Other Grains/Cereals/Fermentable Bases

Oats

Oats are typically used sparingly and mostly in one particular style of beer: oatmeal stout. The inclusion of oats creates a remarkable smoothness plus a hint of sweetness. Oats account for between 5 and 10 percent of a typical oatmeal stout’s grain bill, and usually they appear on the lower end of that range. Too much oat content could make the beer unpleasantly viscous.

Rye

Rye beers have become incredibly popular in recent years—and it’s no coincidence that the demand for whiskeys based on the same grain has been surging, as well. Rye bestows some tart, spicy, and black peppery characteristics to beer, elevating it to a whole new level of complexity. Unlike whiskey, though, there aren’t any 100 percent rye beers. Rye is more like a specialty malt used in conjunction with the main grains, usually barley. Grain bills with 10 to 20 percent rye tend to be the norm. India pale ales are particularly welcoming environments for rye because the spicy elements of the grain complement the floral, citrusy hop bitterness of that style. However, rye has been known to find its way into porters and stouts as well, offering a nice contrast with the roastier elements of those dark brews.

Corn

Corn is also frequently used as a fermentable base in beer and traditionally has gotten a bad rap among beer enthusiasts for its use to lighten flavor and body (thanks to its lower protein content) in industrial lagers. However, the tide is turning somewhat as folks are beginning to realize that it has a place in many quality recipes and, in some cases, actually enhances flavor. Yuengling has used corn in its famous lager since its creation nearly two hundred years ago; back in the nineteenth century brewers had to use whatever was readily available to them. The Pennsylvania brewer continues to use corn to this day, giving its lager a distinct sweetness. (Corn is actually sacred when it comes to bourbon, but it’s been fighting to improve its reputation in beer. And, in a lot of ways, bourbon is just distilled and aged beer, so what’s the problem?)

Rice

Rice is the second most common adjunct—any fermentable ingredient that supplements the main grain—used in American beer and had been maligned by beer geeks as much as rice had been. Rice doesn’t impart the kind of sweetness that corn does. For that reason, it plays fairly well with others and doesn’t detract from the dominant characteristics of the other malts in a particular recipe. (And just remember that it’s the crucial component of the much-venerated Japanese beverage, saké. So it’s all a matter of context.)

Candi Sugar

This sweet adjunct is a staple of strong Belgian and Belgian-inspired brews like Dubbels, Tripels, and Quadrupels. Its services most commonly are sought to boost the alcohol content of beer without adding any extra viscous body. It has a secondary use in bottle conditioning, as it’s frequently added to a bottle to jumpstart the yeast and inaugurate the secondary fermentation/natural carbonation.

Sorghum

The use of this cereal is fairly common in parts of Africa, like Zimbabwe and Botswana (there’s a lot of it there, versus other grains), but sorghum barely registered as a brewing option in the United States until more and more people were diagnosed with Celiac disease. Sorghum is gluten-free, so it’s a workable barley alternative, if not the tastiest option. However, as the gluten-free movement grows, brewers have been getting more creative with their beers sans gluten and have developed flavorful alternatives with and without sorghum.

Sweet Potatoes

The use of sweet potatoes in brewing originated, for the most part, in Japan. And that’s for two reasons: one, the starchy vegetables are immensely popular there, and two, taxes. Japanese brewers are taxed based on their creations’ malt content, creating the necessity for a category of low-malt beers called happoshu. The sweet potato is just one of the fermentable sources that has been used to replace some of the malt content. American brewers have been experimenting with sweet potatoes, as well. One of those, Epic Brewing Company, did it to create a flavorful gluten-free beer. Sweet potatoes worked much better than sorghum.

Microflora (Yeast, Bacteria, and Their Ilk)

We’ve covered two of the four primary components of beer thus far. We won’t get too much into water because most people have a general concept of what it is and its role in brewing. Any further description would veer too far into technical territory. So that just leaves the yeast.

Before anyone got savvy about cultivating different strains of these wee beasties to produce various desired flavor profiles, there basically were two types of yeast with fancy-sounding names: Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Saccharomyces pastorianus. The former is of the top-fermenting variety (ales), and the latter is of the bottom-fermenting sort (lager). But with those two very general names, we’ve barely scratched the surface.

There are a lot of variants under each, and sometimes pastorianus is referred to as Saccharomyces carlsbergensis. The origins of each can be found in their names. Pastorianus is named after Louis Pasteur, while carlsbergensis is a nod to the Danish brewery, Carlsberg. It was in Carlsberg’s lab that fermentation scientist Emil Christian Hansen isolated and cultivated yeast back in the 1880s. The name carlbergensis has mostly fallen by the wayside in favor of pastorianus (Pasteur is much more of a household name). “Cerevisiae,” interestingly, is remarkably similar to the Latin word for beer, cervisiam.

There’s also another lager yeast, Saccharomyces uvarum, which is sometimes used as an umbrella term for those bottom-fermenting species. However, uvarum is widely viewed as a lager contaminant.

And here’s where things get really crazy. Brewers play around with all sorts of microscopic wildlife to impart strange and wonderful flavors to their products that wouldn’t emerge through conventional yeast alone.

Brettanomyces

A microorganism genus that has drawn a near-religious devotion among makers and lovers of wild ales has been Brettanomyces, usually shortened to “Brett.” (Everyone wants to be a friend of Brett!) And it’s a rather counterintuitive development, as the funkiness such yeast would impart, in most beer and other fermented beverages, would be considered off-notes. If Brett got anywhere near a batch of wine, that wine would be dumped. The same would be true for most beers as well, but leave it to the Belgians to intentionally enable such an unwelcome invader to propagate. There are many variations within the genus; the one most lovers of Belgian-style wild ales are likely to have encountered is Brettanomyces bruxellensis. The name should be the giveaway, as it has “Bruxelle”—as in the French spelling of Brussels—embedded right in it. It’s this variety that does all the dirty work in lambics, gueuze, Flemish sours, et al. (We’ll get into those in greater detail later.)

There’s a reason the ales brewed with Brett are called “wild.” There’s usually no predicting just what the wee beasties might do, and that’s part of the fun. The words that frequently come up to describe the typical notes for which Brett is responsible are horsey (more like the blanket one would put on a horse, not what, umm, comes out of a horse) and barnyardy. Not exactly appetizing in most contexts, but it is one of those acquired taste kind of things. American brewers have been experimenting with the stuff so much that you can’t really call it “experimenting” anymore. However, that doesn’t necessarily make it mainstream. Ninety-nine percent of whatever most people are likely to drink probably won’t contain it.

Brettanomyces are not the most efficient little critters, either. Brewers need a great deal of patience when working with Brett. For a Brett beer to reach its prime, it often will take a year or two—a lifetime when compared with most styles.

Lactobacillus

Those who recall their high school biology class will recognize the root word bacillus. That puts it in the bacterial, rather than the yeast, domain. Bonus points for remembering that it’s of the rod-shaped variety (versus the coccus, as in strep-throat causing streptococcus, which is more spherical in appearance).

Lactobacillus is the culprit (in a good way) responsible for the character of many types of sour beers—each with varying levels of funk, but typically not nearly as much funk as beers resulting from Brett’s handiwork. It’s part of the same group of bacteria that convert lactose, the sugar found in milk, into lactic acid (which is one of the active components of yogurt, cottage cheese, and even sourdough bread). It does the same thing with the sugars in beer (versus converting them to alcohol like other microorganisms do). Beer-wise, it’s what gives the Berliner Weisse is signature tartness. It’s also present in Belgian sours and another indigenous German style, gose. (More on those later.)

Pediococcus

Like Lactobacillus, Pediococci are bacteria. As noted, coccus bacteria are ball-like. Aside from the shape, the Pedicoccus (affectionately known as “Pedio”) bacterium shares a lot in common with Lactobacillus; it, too, converts sugar to lactic acid, but it doesn’t produce any carbon dioxide as a byproduct of the fermentation process. These bacteria frequently contaminate beer, giving it a kind of buttery flavor—the calling card of diacetyl, the compound that Pediococci produce—but, when controlled, they can be harnessed for certain desired sour components. They’re usually used in partnership with Brett, as Brett tends to cancel out the diacetyl present in the wort.

We can devote an entire microbiology course to these crazy little creatures. But if you wanted a science lesson, you’d be reading another book.