CHAPTER 9

Preventing Addiction

In this chapter, we explore the best ways to prevent addiction from starting, focusing on the relationships of adults and teenagers.

Prevention of addiction is everyone’s responsibility, one that is never finished. The most critical time for prevention is before youth reach the ages of twelve to twenty, when nonmedical drug use usually begins. The key to preventing addiction to alcohol and other drugs is the family team, parents and children working together to achieve shared goals. Families should begin at the earliest ages, certainly before children reach the age of eight or ten, talking about the family team and its goals. The family goal that transcends all others is to help the children grow up to become healthy, productive, and independent adults. To do that they must be free of addiction to alcohol and other drugs.

In this chapter, I emphasize family-based prevention of addiction. There is an important environmental role for prevention that is more fully explored in the preface and in Chapter 12 of this book, where we consider policy options for prevention. In this chapter, we explore the role of character disorder in addiction and the boundaries for social drinking of alcohol. When it comes to prevention of addiction, there are no guarantees. A family can do everything right and still have problems with addiction. Equally remarkably, families can do everything wrong and still avoid addiction in some family members. Prevention is a process of reducing, not eliminating, the risk of addiction. The risk of addiction to alcohol and other drugs cannot be eliminated completely because it is part of our shared human vulnerability.

The family that wants to prevent addiction must talk with and listen to each other with the clear understanding that the children will be in the parental home for a relatively brief time, until about the ages of eighteen to twenty-five, when they will leave the parental home and go off to make their own homes. The children’s position in the world as adults, including their economic status, will be determined by their own choices and achievements, not by those of their parents. While the children are at home, they need to work with their parents to have good childhoods and to prepare themselves for their own long life of self-support. While the children are in the parental home, their parents provide for their needs as best they can.

Both parents and children owe each other love and respect. Families do not work well if the children do not respect their parents and if the parents do not care for their children. Families do not work well without open communication and honesty. Families need clear rules about the behavior of the children, especially when it comes to respect for adults, work around the house and at school, and the use of alcohol and other drugs. A successful family can come in a variety of structures and at any income level, but success in the prevention of addiction is unlikely without clear-cut rules rejecting youthful use of alcohol and other drugs.

To achieve the primary goal of preventing addiction, the family team must develop working processes for everyday life that take into consideration the unique characteristics of the family and of each individual family member. Like any other team activity, this involves sustained practice and effort over time. It involves people working to help each family member achieve his or her unique potentials.

Each family will approach the process of prevention of addiction differently. My suggestion, however, is that whatever approach your family takes be put into words in ways that everyone understands so that the roles of each family member are clear. There needs to be plenty of room for both pleasure and hard work for all family members, for time alone as well as for time together. Preventing addiction means tough love about drug and alcohol use, but it also means using solid principles to live good lives. There is more to preventing addiction than simply “saying no” to drugs and alcohol, although that is a fundamental part of a successful addiction prevention program.

Making prevention work in the family means playing the game of life within life-sustaining rules, which are often found in values that transcend the family. For many families, this means religious values and an active, personal relationship to God or a Higher Power. It certainly means living within the law and being honest. Children are most likely to prosper if they work with their parents, accepting parental authority, and if they make the best use of their childhoods to prepare themselves to leave their parents’ home after their teenage years and support themselves financially.

Pseudoadults and Pseudochildren

In North America in recent decades, the boundaries between childhood and adulthood have become blurred. Youth are given freedoms and choices during childhood that are best restricted to adults, such as the use of alcohol and other drugs and choices about sexual activity. This downward movement of previously adult choices has disastrously eroded the experience of childhood, a time formerly protected from such choices by adults so as to promote the development of young people. Children who use alcohol and other drugs, and who are sexually active, are pseudoadults. They exercise the choices of adults without the responsibilities of adults. When pseudoadults get into trouble as a result of their choices, their parents rescue them, thus depriving them of the painful but valuable lessons that life provides to adults.

When people enter their twenties, thirties, or forties without becoming financially and emotionally independent of their parents, they often continue to act as if they were children, expecting their parents to rescue them from the negative consequences of their own choices, choices that often involve the use of alcohol and other drugs. Such people are pseudochildren. They act like adults, but they do not carry adult responsibilities, and they expect protections from their parents that in the past were usually restricted to children.

A thirty-seven-year-old businessman whose cocaine use led to the loss of his business and his marriage, as well as to criminal charges, returned home to live with his mother and father. He had no car with which to get to work and no money to pay for a lawyer to fight his entanglements with the law. His parents provided a home, a car, and a lawyer. They struggled with his repeated relapses to cocaine use and his dishonesty, but most of all, they struggled with his anger at them and his frustrated sense of entitlement. They were terrified that if they did not help him, he would die of his disease. This man was a pseudochild, locked in a relationship with his codependent parents. Although this is a tragically common picture in North America today, it is not as common as teenagers being treated by their parents as adults. Both pseudoadults and pseudochildren are at high risk of addiction to alcohol and other drugs. Both are primary targets of addiction prevention, and both represent common failings of the modern family.

All too often, families do not clearly define a teamwork process or family goals. Prevention is subverted by seductive assumptions and misunderstandings. Many children come to think of their childhood as a time to “have fun.” They see work and adult responsibilities as their enemies, to be postponed as long as possible. Surprisingly, the parents often share these crippling assumptions. When high-risk teenagers do work, they think only of the current wage, not of the larger potential of the job to provide experience and future rewards for themselves and for their communities. For pseudoadults, childhood appears to be freedom; self-supporting adulthood looks like prison. At-risk children, often with the active but unwitting connivance of their parents, attempt to postpone the real independence of adulthood as long as possible. They act as though they will never need to support themselves or as though they can take care of their problems and begin to work hard once they are adults, at some vague, faraway future time.

Parents may be so caught up in their own problems and needs that they do not help their children face what has to be faced if the children are to fulfill their personal potentials. If the parents or the children have disabilities, it is often all the more difficult for parents and children to keep their focus on the need for hard work and on their roles in the family team. Both parents and children can use disabilities and hardships as excuses for poor performances rather than as incentives for greater, better focused efforts. The plain truth is that the only solution to any disability is to work harder. No other approach has ever worked. Anyone who does not tell this truth to disabled people is not doing them a favor. Hard work is not the enemy of either children or parents; it is their friend. A good life is not an easy life, but a life of fulfilling personal potentials and of helping others. A good life is a life in balance with time both for work and for healthy play.

Young people who use alcohol and other drugs frequently blame others, especially their parents, for their problems. Many adults, often those most dedicated to the welfare of youth, agree. This is unfortunate. The point of this book is that all of us are responsible for our own lives and for our own choices. This includes young people. Many drug-using youth come to my office, brought by worried parents, saying that their problems are “my parents.” Complaints are legion from drug-using youth, but mostly they relate to parents being too strict or having expectations that are too high.

Young people, whether or not their parents have serious failings, need to recognize, and adults need to help them recognize, that they are almost always better off working with their parents than against them and that parents deserve respect, whatever their imperfections in the eyes of their children. I remind young people that in the rest of their lives no one will ever again give them what their parents are giving them: unearned financial support, including food on the table, a roof over their heads, and an opportunity to learn and grow into their own unique independent and adult selves. Bosses will insist that they work long and hard for their paychecks. Spouses will require tremendous work to support the family. Friends will not provide the financial support that parents do.

Even the most difficult parents have something positive to offer their children, and, in any event, there are plenty of positive role models around for young people to emulate: teachers, coaches, neighbors, friends, religious leaders, and others. If children are to make the best of the opportunities they have, they need help in focusing on their primary work, which is school, and on their major goals, which are to develop their skills and their intellectual and moral lives. Complaints and excuses do not help young people grow up to become happy and healthy adults. A genuine respect for parents and other adults in authority, including teachers, is a good place to start for all young people.

The Ten-Point Plan for Prevention

Here, based on the principles outlined in this book, are ten practical ways to drug-proof your child:

1. SET A FAMILY STANDARD ON DRUG AND ALCOHOL USE. Tell your children the family rules about the use of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drugs early, when they are in grade school or even before. Let your children know what your expectations are for their use of alcohol and other drugs, including marijuana and cocaine. Take a stand on smoking cigarettes. No use usually is the best rule for children, including teenagers, for cigarettes, alcohol, and other drugs, but whatever your family rules, make them clear to everyone in the family. It may help to remember that both drinking alcohol and smoking cigarettes are illegal for teenagers. Remind everyone often of the family rules on the use of addicting drugs. Here is an important fact: all of the terrible problems caused by alcohol and other drugs can be prevented completely by not using alcohol and other drugs.

2. ESTABLISH REASONABLE CONSEQUENCES FOR VIOLATIONS OF THE FAMILY RULES. Examples of effective punishments include loss of privileges such as driving a car or being with friends away from the family’s supervision. Make the consequences for violation of the family rules clear in advance and impose them without exception every time there is a violation of the family rules about the use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs. The best punishments usually are those that are swift and painful but fairly brief. Not being permitted to use the family car for the next two weeks is better than not being permitted to go out with friends for the next six months, for example. Make punishments that are enforceable. Do not make punishments so painful for the children or for the parents that they are unendurable.

3. SET ASIDE A TIME EVERY DAY TO TALK WITH YOUR KIDS ABOUT WHAT IS HAPPENING IN THEIR LIVES, HOW THEY FEEL, AND WHAT THEY THINK. Starting from infancy and continuing through teenage years, let them talk while you listen, giving them your full attention. Actively listen, respecting your children’s experiences and feelings. Kids grow up fast. Make time every day to listen to your children, to let them know that you value them just the way they are, and that you want to know what they think and what they feel. You do not have to solve their problems or give them advice. Just listen and care. That is a great gift to anyone. It is especially important to give that gift to your children every day, even if only for a few minutes. Do not reinterpret your children’s experiences into those of your own life or give them high-flown lectures on what they should do or feel. Respect their feelings and experiences as their own. Love your kids and appreciate their troubles as well as their triumphs, without attempting to take over their feelings and experiences.

4. HELP YOUR CHILDREN ESTABLISH PERSONAL GOALS. Define with your children simple, practical goals that can be reached, and help your children reach them. These should include academic, athletic, and social goals. The goals should be both short-term (the next day or two) and long-term (the next month or two). Help your children accept and learn from their inevitable failures. Failures are growth opportunities and not reasons for giving up. Do not set goals so high that your children often fail. If you do that, the children will feel it is hopeless to try. Set small goals that are relatively easy to achieve. Feel good about your children when they achieve their goals.

5. KNOW YOUR CHILDREN’S FRIENDS AND SPEND TIME WITH THEM. Know your children’s friends and the parents of your children’s friends. Both your children’s friends and their parents can enrich your life as well as help you to be a better parent. Your kids are part of your family, and you are part of their family. Socialize together; share your lives. This does not mean that there is no time for privacy or separateness for adults or children, but it does mean that the common ground, the shared experiences and relationships, are important to the health of the entire family. When common emotional ground shared by parents and children in the family is lost, then both parents and children lose, with children’s drug and alcohol use being more likely to start and more likely to progress to bad outcomes.

6. HELP YOUR CHILDREN FEEL GOOD ABOUT THEMSELVES AND THEIR ACHIEVEMENTS, LARGE AND SMALL. Get excited about what your kids care about. Life is an adventure. Share the adventure with your kids; you will not have them with you for long. Parents too often feel either disengaged from the lives of their children or as if they have to run their children’s lives. It is important that parents learn to enjoy their children’s lives, to share with their children so that the children understand what is going on in the parents’ lives, and the parents learn what is going on in the children’s lives. This means that sadness and joy, and other human feelings, get communicated between parents and children in an open, direct, and respectful way.

It is fun to care about someone else. It is fun for people to care about you. Friends come and go, but families are for a lifetime. For family life to be a positive experience, it is important that children and parents openly and honestly share their lives regularly, respecting both what links them and what separates them. Know what mountains your children are climbing in their lives’ adventures. Share the tough journey up, the view from the peaks, and the pain and frustrations of the falls and disappointments.

7. HAVE A SYSTEM FOR CONFLICT RESOLUTION. Your kids will not agree with you about all the family rules of the house. Parents are in charge, and their decisions are the rules. Parents carry their authority best when they are open to appeals from their children. Establish a process for review, such as seeing a religious adviser, a mutually respected family member, a neighbor, or a counselor if conflicts develop. Parents need to be open to challenges from their children to their authority. Parents also disagree with each other about how to handle their children, especially when the children have problems. The more serious the children’s problems, the more likely the conflicts between parents, and between the parents and the children. Parents can use the same system for conflict resolution for conflicts between themselves. The strong parent is open to new learning and adapts to new challenges, many of which are unforeseen.

8. TALK ABOUT YOUR CHILDREN’S FUTURES EARLY AND OFTEN. What do you expect from your kids? What can they expect from you? Children need to know that they will be with their parents for a relatively short time until they are grown up and leave home. Help your children know that they will soon be out of the parental home, paying their own bills and making their own rules. This change from childhood to adulthood comes at various ages but usually between eighteen and twenty-five. Children become adults when they leave their parents’ homes and financially support themselves, not when they get a driver’s license, turn eighteen, or go to college. Until children are adults who support themselves financially, they need to accept parental authority. That authority needs to be exercised by the parents as a trust for the children’s welfare.

9. ENJOY YOUR KIDS. One of life’s greatest joys is having children in your home. Work with your children to make your home a positive place for everyone. That means family teamwork and mutual respect. It also means accepting, and appreciating, that your children are each unique human beings with interests, abilities, and goals that are different from you and anyone else. This diversity and uniqueness needs to be respected and even celebrated, not suppressed or frustrated.

10. BE A NOSY PARENT. Ask your children questions; know where they are and who they are with. This information is necessary for you to be an effective parent. As a parent, you cannot fly blind while piloting a family and avoid crashing. Let your children know that you are being nosy because it is your job as their parent and because you love them.

These prevention techniques work best when they are put in place early in children’s lives so that they are familiar with the operation of the family team and have a clear understanding of the healthy, realistic roles of parents and children. It is difficult to confront a drug or alcohol problem in a teenager and try, at that point, to establish parental authority for the first time. By then, typically, the youth has been making his or her own often impulsive and irresponsible decisions for many years and has spent time with other youths who are living with uninvolved and/or dangerously permissive parents. It is far harder then to regain parental control than it is to start when the children are infants so that they can grow up with this understanding of their roles and goals as part of the family team.

Character Disorder: A Distinguishing Feature of High-Risk Youth

Prevention of addiction is easier with some youth than with others. Families with children at low risk of addiction have a relatively easy time following this ten-point plan for family-based prevention. When these families fail in their efforts to live wisely, they often suffer no adverse consequences. They often think of addiction prevention as fairly easy. On the other hand, families who have children at high risk of addiction will read this ten-point list and see that, despite their best efforts, their children dive into the use of alcohol and other drugs the way young ducklings dive into water. Families with low-risk children can afford the velvet glove approach to addiction prevention. Families with high-risk children need to take out the iron fist of parental authority, keeping their children under tight supervision.

Families with high-risk children deserve and need support, which often is best found through a parent-support network with other families coping with similar problems. Many junior and senior high schools now have active parent-support programs. Another good place to find support for families dealing with high-risk youth is at an Al-Anon meeting, as described in Chapter 11. Many parents who are concerned about preventing alcohol and other drug problems in their children also can find help at an Employee Assistance Program (EAP) at their places of work. Larger employers are likely to have EAPs, which can discuss concerns and help parents find support, including treatment for their children or for the entire family, when that is needed.

The toughest challenges are youth who suffer from character disorder, which is a common and relatively mild form of antisocial personality disorder. At its simplest definition, this means that youth who are at high risk of addiction to alcohol and other drugs are willing to be dishonest with anyone who may get in their way, including their parents, their teachers, and anyone else in authority. High-risk youth are the true test of any addiction prevention effort. High-risk youth are attracted to alcohol and other drugs. No effort to stop their headlong dive into addiction will stop all such youth from doing their own personal exploration of addiction. (See Chapter 7 for more information about character disorder and Type I and Type II addicts.)

Dishonesty: Addiction’s Essential Requirement

Active addiction requires lying and dishonesty, the willingness to live outside the conventional boundaries of family and community values. To repeatedly take an addicting drug despite social disapproval requires that one value highly personal and immediate pleasure (the drug high) above responsibility to others or even one’s own long-term self-interest.

Lying is like drug use in that it produces pleasure now, even though it almost always produces eventual pain. In working with addicts and teenage drug abusers, I have learned a lot about lying. I have learned that the more a person loves the drug abuser, the easier it is for the drug abuser to lie, because lying is simply a matter of telling the caring person what that person wants to hear. The more the person loves the addict, the more eager the person is to hear the lie and the easier it is for the addict to get away with the lie in the short run. I have also learned that lying does not work in the long run, although it sometimes works in the short run.

Lying to someone who cares for you is like avoiding homework or spending money you do not have. It comes to a bad ending, usually in a big hurry. But because high-risk people typically do not think ahead, they are blind to the inevitable outcomes of their dishonesty and shortsightedness. In contrast, most anxious people are compulsive truth tellers. They find it hard to lie, even about trivial things. I asked an anxious teenager why he did not lie. He told me: “It is not because I am moral or religious. I can’t lie because I am sure I will be caught and punished.” This attitude of an anxious person could not be more different from the attitudes of character-disordered drug addicts and alcoholics.

The Good and Bad Effects of Fear and Fearlessness

When I see this distinction between character disorder and anxiety disorder in teenagers, as I often do, I see a simple distinction in their attitude toward homework. High-risk kids do not do homework because it is pain now, pleasure later. If the teenager is thinking only of the next ten minutes, homework is not an attractive activity. In contrast, anxious kids often do their homework to the exclusion of other important activities, including spending time with peers, as they worry excessively about the next test or even about what college they will get into in a few years.

As a psychiatrist, I find myself saying to high-risk kids, “Think about the future,” “Think about what is likely to happen to you if you do this or that,” and “Worry more!” Alcoholics Anonymous puts it this way: “Think through the drink.” In other words, do not just think about the good feelings of using alcohol or other drugs, but think about what comes after the high and then think about what comes after that. This calculation of future consequences, as one of my drug-abusing patients told me, wrecks the fun of drug use. Right, that is reality.

With anxious teenagers, I often say, “Stay in the present; let the future take care of itself,” and “Worry less about tomorrow; have fun now.” High-risk kids think primarily of positive future outcomes. Anxious kids think mostly of negative future outcomes. “A” students worry about exams. “F” students rarely worry about tests or grades. When “A” students come out of exams, they often feel as if they have flunked. High-risk kids come out of exams feeling that the exams were easy and that they did well, even when they actually failed the tests. These fundamental differences in character can be seen in all ages, not just in kids. People who worry a lot are less likely to use drugs; people who do not worry enough are more likely to use drugs.

When I talk with high-risk youth in my practice about dangerous behaviors, I can say, “Three out of four people who do what you are doing are dead within a year.” My high-risk patients typically reply, “Those are the best odds I have had in a long time. I am not worried at all. I know that I will be in the 25% who make it just fine.” For high-risk people, the future holds limitless prospects for happy, lucky outcomes. On the other hand, when I tell my anxious low-risk young patients, “One in a thousand people who do what you are doing may have a relatively minor illness as a result,” they are frightened by the danger. They are sure that they will be the one person in a thousand who has the problem. For characterologically low-risk people, the future is scary.

High-risk people may ride motorcycles, and anxious people may be afraid to drive on freeways or fly on commercial airplanes. Most high-risk people, especially high-risk youth, are not interested in exciting or risky activities that take a lot of work. They like passive, quick, intense pleasurable rewards. They do not seek risks; they seek rewards. For them, risk is a by-product of reward, not the goal in itself. Mountain climbing or white-water rafting are not usually preferred activities by character-disordered drug abusers; neither is a pleasure-producing activity that has a delayed payoff and that takes a lot of self-control or social control, such as organized sports. Drug use does not compete with wilderness backpacking in the minds of most drug addicts. Wilderness survival training, mountain climbing, scuba diving, and skiing all take planning and sustained effort. These activities are subject to authority and rules, making them unappealing activities to many drug addicts who are not attracted by the rewards of delayed gratification. Drug highs are quick, easy, and personally controlled. Drug highs fit the character of high-risk people like a glove fits a hand.

Rewards: Now and Later

High-risk people are said not to learn from their mistakes. That is not true. They do learn from their short-term successes—they believe that what works right now is good. Most high-risk people cannot see into the probable negative future, so they repeatedly do things that get them in trouble. Each time, when asked why they did the dumb thing that got them in trouble again, they say simply that they thought they could get away with it or, even more commonly, that they never thought at all about what would happen after they acted as they did. People have called this the illusion of invincibility, but, more accurately, it is blindness to the likely future consequences of pleasure-driven behaviors.

There are some other obvious correlates of these opposite character styles. High-risk people lack empathy, a respectful sense for the feelings of others. High-risk people are aware of other people’s feelings, but they do not feel pain when they hurt others. High-risk people think of other people’s feelings mainly in terms of what they can do to manipulate those feelings to get their own way. High-risk people are relatively unconcerned about punishment. When anxious people are punished, they feel devastated for long periods of time even by mild disapproval. In contrast, high-risk people are relatively oblivious to punishments. As one teenager said when he had been punished by his parents, “Is that all there is to it?” A typical high-risk response to a problem, such as being found out in a lie or drug use despite solemn promises not to use, is, “I said I’m sorry. What more do you want from me?” or “I don’t know why I did it.”

Most addicted people expect that by simply saying they are sorry all will be forgiven. Here is what one member of Narcotics Anonymous said at a meeting I attended, when the topic of the meeting was making amends for the harm that addicts had done to other people:

When I was using drugs I always said I was sorry when I got caught, but I knew all along that saying I was sorry meant I was just going to do it again. Other people seemed to think I meant that I would not do it again. I never meant that. They kept expecting me to act that way, even though I never did. They said I didn’t learn from my experiences, but they didn’t learn from their experiences either. I never figured them out, and I guess they never figured me out.

Future Thinking

High-risk people do not save money. When I work with people with a character disorder, I can watch their savings balances and see how they are doing in therapy and in their lives. If they live financially in the red, their character disorder is continuing; if they live financially in the black, they are getting better. Growing debt reflects more character disorder; saving money reflects less of it. When high-risk people have money, and they sometimes do, they put it at risk with investments that hold out the promise of quick gains, or they simply spend it on something they want right away. Such investments seldom work out, which is why they are called “high risk.” This pattern of being unrealistically optimistic about the future creates some truly phenomenal debts for those relatively rare, financially successful high-risk people.

High-risk behavior is not all or nothing, so some high-risk people have this potentially destructive character trait under fairly good control, with the result that they can do well in life, often because they are congenitally optimistic and willing to take big risks. This concept of a “little bit of character disorder” helps to explain the people who succeed in many areas of life but then have serious addiction problems. Some of these people have a smaller dose of high-risk characteristics. They win some of their high-risk gambles.

Anxious friends, family members, and associates often marvel at the seemingly magical fates of mildly character-disordered people. When anxious people do gamble and take other risks and lose, as they commonly do because people who take risks lose sometimes, they rapidly become “risk averse.” When high-risk people take risks and lose, they habitually pick themselves up and do it all over again. Just as high-risk people are relatively impervious to punishment, so too are they relatively impervious to failures. The other side of that coin is that many worried people find that even when they succeed, they still have trouble believing they will succeed the next time, feeling they were merely “lucky” and that surely the next time their luck will fail.

Life is not fair. This is nowhere more true than with character disorder. Some people have a lot of it, and some have a little. There are some obvious correlates of character disorder. Age is one. The character disorder syndrome is most intense between the ages of about fifteen and twenty-five. People with character disorder can get well with help, especially help from the Twelve Step programs. Character-disordered people mature out of their problem for many reasons. They get well partly because they learn, however slowly, from the pain they cause themselves and partly from changes in their nervous systems as the biological fires that fuel their high-risk behavior dampen with age. When people get well from character disorders, they often continue to show interest and ability in two areas, both related to their underlying character traits. On the one hand, they are often risk taking and entrepreneurial, and, on the other hand, they are interested in human relations and human service activities because they are often extroverted.

Males are more likely to suffer from the character disorder syndrome than females, again for both biological and social reasons. Some environments foster this sort of behavior more than others. Irresponsible, neglectful, permissive, or indulgent families tend to produce more high-risk kids than do other families. But whether a person has character disorder or not is often observed at an early age and apparently biologically determined. I see many families with several children, only one of whom has this high-risk character even though all the children have been raised more or less similarly. Many of these families are quite exemplary. Conversely, I also see some very dysfunctional families that produce healthy children. In this, as in most human behaviors, it is not just nature (the genetics) or just nurture (the environment), but it is both that cause the patterns of behavior we see in ourselves and those around us.

Coping with High-Risk Children

There is no simple solution to the problems created by high-risk children for themselves and for those who care for them. The ten-point prevention plan is a good starting point in the family and in social institutions dealing with children. It is helpful to talk directly with high-risk children about the difficulties they create for themselves by thinking unrealistically about present rewards rather than about probable future consequences of their choices. It also helps to state clearly the family rules and to enforce them consistently with love. High-risk children who are still supported financially by their parents need to be held to the standard of respecting their parents and others in authority. High-risk youth who have left their parents’ homes need to be held to the standard that their parents will not rescue them from the bad choices that they make.

Drawing clear lines between childhood and adulthood is essential in dealing with a character-disordered child of any age. Psychotherapy can sometimes be helpful, but high-risk people themselves are seldom interested in psychotherapy because it is experienced by them as a barrier to their being able to do what they want when they want to do it. Psychotherapy is more likely to be useful for family members who must deal with high-risk people because they create dilemmas for those who love them.

When all looks dark and hope is hard to hold on to, recall that time is on the side of recovery because many character-disordered youth mature out of the worst aspects of their problems, although this can take until they are into their twenties, thirties, or even beyond in especially difficult cases. Parents need to keep up hope and to work with other parents of high-risk youth to find the best ways of helping their children stay on course for a good life as adults, supporting themselves.

Four Simple Boundaries for Social Drinking

Prevention of addiction requires a clear understanding of the place of alcohol in family and community life. Although alcohol use by adults is legal, and although many adult alcohol drinkers have no health or behavioral problems as a result of their alcohol use (unlike cigarette smokers), alcohol poses a significant health risk for adults. Underage drinking is even more likely to generate serious health risks, from driving accidents and suicide to AIDS and academic failure. Although the decision not to drink alcohol removes all of these health risks, many North Americans choose to drink. Although most drinkers are convinced that their own drinking is safe, the new and growing intolerance for cigarette and alcohol use, by adults as well as by youth, raises important questions for social drinkers. Is my drinking safe? How can I tell if I have a drinking problem, since denial is a hallmark of alcoholism? There are four understandable and uncontroversial ways to prevent alcohol-caused problems:

- Don’t drink alcohol if you are under the legal drinking age of twenty-one.

- Don’t drink alcohol while pregnant.

- Don’t drink alcohol within four hours of driving a car or going to work, because of possible impairment and associated safety and performance risks.

- Don’t drink alcohol at all if you have a personal history of drug or alcohol addiction. Abstinence from alcohol use also may be prudent for people who have parents or siblings who are alcoholics or drug addicts.

Drinking alcohol in pregnancy deserves special attention because of the concern for the health of the unborn child. The best and simplest rule is not to drink alcohol at all while pregnant. Drinking up to two or three drinks of alcohol a week during pregnancy may not harm the mother or the unborn baby. However, because there is no absolutely safe level of alcohol for the unborn baby, zero is the safest number when it comes to drinking alcohol during pregnancy. Many women today take this clearly safe course, and they do not drink alcohol at all when pregnant.

Some women are concerned about calories during pregnancy as well as about their baby’s health. Because alcohol is the emptiest of calories at about 150 calories a drink, this fact alone is enough to convince many pregnant women to stop drinking alcohol altogether while pregnant. Maternal alcohol use in excess of two drinks a day on a regular basis, and even repeated but not daily consumption of five drinks or more a day are serious risk factors for the unborn child, as is maternal nonmedical use of other drugs such as cocaine and marijuana. Lower levels of alcohol use may also become problems for either the mother or the unborn baby. Abstinence from drinking alcohol during pregnancy is the simplest and the safest course to follow.

Traffic Signals for Social Use of Alcohol

For adults who choose to drink alcohol, I use a “stoplight” system. This is a recommendation that is both personal and controversial, unlike the four boundaries described above. To understand the stoplight system, a drink is defined as twelve ounces of beer, five ounces of wine, or 1.5 ounces (a standard jigger) of distilled spirits. Each of these amounts contains about the same quantity of pure ethyl alcohol, about one-half ounce. Drinking up to two drinks in any twenty-four-hour period and up to four drinks in any week falls into the green light zone. This is a generally safe drinking level for everyone over the legal drinking age who is not pregnant and who does not have a personal history of drug or alcohol dependence. Most American social drinkers stay within this green light zone without making any effort to control their drinking. Few, if any, alcoholics drink alcohol at this low level except occasionally and usually briefly, when they begin to drink for the first time in their lives or during periods when they make great efforts to cut down their use of alcohol.

Drinking up to four drinks in any twenty-four-hour period and up to ten drinks a week is the yellow light zone. This is more alcohol than most social drinkers choose to drink and is potentially dangerous. Apparent drinking at the yellow light level is often the result of problem drinkers making a big and usually temporary effort to control their drinking. Yellow light drinking may also be a temporary stage in a progressive increase of drinking leading to higher levels of alcohol use. Drinking in the yellow light zone is seldom a stable, long-term drinking pattern in North America, although it is in some wine-drinking countries where widely accepted, traditional social controls restrain many drinkers from further escalation of their alcohol use. Most social drinkers in North America find that drinking the amount of alcohol in the yellow light zone is unpleasant. Those North Americans whose drinking puts them in the yellow light zone need to recognize that they are at risk for serious alcohol problems.

Worrying about your drinking is generally a good reason to stop drinking entirely or to reduce your drinking permanently to the green light zone of four drinks a week or less. Healthy social drinkers do not worry about their drinking and they do not count their drinks because they drink so little, usually less than four drinks a week. If the green light goal is not easily reached and maintained without effort, then it is wise to seek help from Alcoholics Anonymous and/or from a professional in the treatment of addiction. Many drinkers who report drinking in the yellow light zone are alcoholics in denial (that is, they claim this amount of drinking but they actually drink more).

Drinking more than four drinks in any twenty-four-hour period, even on New Year’s Eve, and drinking more than ten drinks a week in any week puts a person in the red light zone. This level of alcohol use is presumptive evidence of a serious alcohol problem. This is not a normal or healthy pattern of drinking. Alcoholics usually socialize with others who have problems with their drinking, which gives a social camouflage to their denial of their alcohol problems.

People with drinking problems find the green light boundaries extremely restrictive and cannot stay within them, except for short periods of time, with great effort. This attitude of heavy drinkers toward alcohol use is an expression of their addiction, of their loss of control over their drinking.

Is Drinking a Little Good for Your Health?

Recently the media has highlighted the claim that drinking a little—up to two drinks a day for men and up to one drink a day for women—may reduce the risk of heart disease as a result of the effect of low levels of alcohol on fat metabolism. These arguments, often promoted by the alcohol industry, are potentially dangerous because they encourage people to drink alcohol. Although a few scientific studies show that moderate drinking has some health value, an important factor is disregarded in this calculation of benefit. Many people who intend to drink no more than two drinks a day lose control of their drinking and drink more than that. When groups of people who succeed in limiting their drinking are added to those who do not limit their drinking, the net health effect of alcohol use is clearly negative.

Calculating the health benefit of moderate drinking while excluding the costs of heavy drinking is similar to calculating the benefits of speeding (more fun driving, quicker arrival at a destination) while excluding the costs of crashes from the minority of speeders who kill themselves and others. For this reason I do not encourage adults to drink alcohol. However, if you never drink more than one or two drinks a day and feel no urge to drink more, it may be that you will have a health benefit from alcohol use, or at least you will suffer no harm. In my experience, most people who say they routinely drink two drinks a day actually drink far more than that amount. The scientific research is clear that drinking more than one or two drinks a day is definitely unhealthy. Heavy drinking is dangerous to the drinker’s health and to people who come in contact with the drinker.

The CAGE Test for Alcoholism

Another simple screening test for alcoholism is the CAGE test. You can take it yourself. Physicians often use it, but it is equally useful for teachers, ministers, and others who want to do a better job of identifying alcohol problems. Here are the four CAGE questions:

- Have you ever tried to Cut down on your drinking?

- Are you ever Annoyed when people ask you about your drinking?

- Do you ever feel Guilty about your drinking?

- Do you ever take a morning Eye-opener?

The key CAGE words to make this screening tool easy to remember are Cut down, Annoyed, Guilty, and Eye-opener.

Research has shown that even a single positive response to any of the CAGE questions suggests the presence of alcohol problems, that two or three positive responses create a high suspicion of alcoholism, and that four positive responses are confirmatory of alcoholism.

Strategies for Parenting: The Hazards of Solving the Problems of the Next Generation

Many parents do not instinctively develop a sense of the family team, or of the central role of parental authority, because when they were growing up either they had parents who were intrusive and negative, or as children they themselves were so self-motivated that they did not need much guidance or structure from their parents. Successful parents often have a hard time with the guidelines I am proposing for families because as children they were self-starters. Their hard work produced success, which began early in their lives. Such successful parents have achieved a great deal in their lives as adults as a result of their hard work over many years, although most such successful people came from families that had relatively few financial resources. Their success was usually based on sustained hard work and, most successful parents are quick to admit, a lot of good luck. These parents want to share their success with their children “so that they don’t have as hard a time as I did,” or “so that they can have the fun in childhood that I was not permitted to have because I had to work so hard from such an early age.”

Parents who come from modest circumstances and had, from an early age, the understanding that whatever success they were to have would be the result of their own efforts had an advantage that they cannot give to their children. This advantage was the incentive to work hard and the tremendous boost to their self-esteem that came from breaking new ground of success in their families. Children of successful parents typically have the opposite experience, which is much more difficult. They live an easy life of relative affluence that they have not earned. They are often indulged by their well-meaning, generous parents. Many successful parents, mistaking their children for themselves at their age, keep waiting for their growing children to manage their lives productively, a wait that can last forever.

Successful parents often fall into another easy trap. They expect too much of their children, figuring that because their children have had so many advantages that they themselves lacked, their children will be all the more successful. This simple logic is flawed in two important ways. First, having unsuccessful parents is a far better incentive to success than having successful parents. Second, successful parents frequently underestimate the uniqueness and difficulties of their personal achievements. They think, and they lead their children to think, that their success was fairly easy.

Both of these errors, commonly made by successful parents, put children at high risk of serious problems as children and as adults, including addiction to alcohol and other drugs. It is better by far for successful parents to share what wisdom they have achieved and to let their kids know what a tremendous challenge there is ahead of them, one only they can manage, in developing their own self-supporting lives. The children’s ultimate situation in life, including their economic standard of living, will be determined by their own work as youth and as adults, not by the status of their parents. Successful parents should honestly tell their children that the parents’ own success is a real impediment for their children, potentially undermining their motivation for hard work and personal achievement.

Parental success commonly leads to lazy children. Plain, realistic talk about this fact is seldom heard in successful families, which is one of the reasons why rich men’s sons are rarely rich men’s fathers. Most successful families have success for only one generation because of this repetitive pattern of family life. Families with substantial wealth face this problem over many generations. It is rare for them to succeed in subsequent generations. Most of the major achievements in the world, and the world’s fortunes, are made by people who come from modest circumstances. This is as true today as it was 100 years ago. It is certain to be true 100 years from today. Few people who are successful themselves ever consider the consequences of their success for their children, that is, the prices that will be paid by their children for the advantages they as parents have given to their children. Even fewer children of unsuccessful parents recognize the tremendous advantages their families have given to them as children, the advantages of needing to work hard if they are to have much in their lives.

Parents who are themselves impoverished and troubled by drugs and alcohol or other problems are often so preoccupied with their own painful lives that they are unable to give much to their children. Some of these parents are harsh with their children; others are neglectful. Neither harshness nor neglect is likely to help children. Children do best with parents who encourage them to solve their own problems, parents who are involved with them on a daily basis but who do not soften the often painful blows of reality for them. Parents help their children when they celebrate their children’s successes, but they also help their children grow from their failures. This is not easy, but it is the most rewarding way to be a parent. It is also the most likely to lead to a happy outcome of family life for both parents and children regardless of the level of parental success.

Families with disabilities in the parents, and especially families with high-risk teenagers, will have the most difficulty with parental authority and family goals. Nevertheless, such families have, paradoxically, a great opportunity for raising healthy and strong children by helping them to see how the family team copes with adversity. Children in families that have few problems do not necessarily have an easier time than those in families with more problems, because the children are likely, sooner or later, to confront many serious problems in their own lives. The sooner children learn that the measure of their characters is their ability to deal with adversity and failure, the better off they will be. On the contrary, families that are closed (humiliated, frightened, or in denial), families that pull apart rather than together when they encounter adversity, and families that lie and deceive each other are unlikely to thrive. They are especially likely to be tormented by addiction, which is a disease of spiritual impoverishment as much as it is a disease of disordered brain chemistry.

Families need to help their children face the fact that having great abilities is of little value unless those abilities are harnessed in productive ways in the children’s lives. All too often, children who are performing poorly in school and elsewhere are told that they have high IQs and other exceptional innate talents. Telling failing children that they have great abilities may help them maintain their self-esteem in the short run, but it will hurt them in the long run if they come to believe their talents will automatically lead to success. This sort of reassurance misleads children about what they need to do to succeed.

Life is scored on performance, not on ability. The biggest determinant of success in life is the ability to do hard and goal-oriented work over a long period. If people, including youth, are not able to work hard and to maintain their efforts, they are unlikely to prosper no matter how great their talents. Many people with modest talents do extremely well in life because of their good work habits. Adults need to explain these facts to children and to help children develop sound work habits. There is plenty of room in life for a highly diverse range of interests and talents, but success in any area of activity, from music to mathematics and from creative writing to athletics, is impossible without steady, hard, and productive work.

Strength in Weakness

It helps children if parents talk openly about their own failures, mistakes, and deficiencies, and the ways that the parents worked to cope with their difficulties. Parents should talk about both their successes and their failures with the children. For many parents, such discussions are disturbing because they seem to undermine the children’s view of the parents as having the answers and of being strong. The opposite is more often the case. Although it is not desirable for parents to harp on their heroic exploits in overcoming problems, it is nonetheless generally useful to children to know of the more serious problems their parents have confronted and what the results of those confrontations have been. Failures in school or at work, health problems, divorce, financial failure, and personal rejection are the typical problems that most families must confront. Each of these problems is a growth opportunity for all family members. Parents can also say that while the kids are at home (that is, still in a child’s role), they will do their best to offer guidance to the children, including setting appropriate limits when health and safety are at stake. On the other hand, once the child leaves the parents’ home and is self-supporting, this parental safety net will be removed and the child will be free (or burdened!) by independence from parental authority.

Preventing addiction to alcohol and other drugs is a shared family project that fits well in the overall family goal of raising children who pursue their own destinies, independent of their parents. Families that have a history of addiction and families with high-risk children are those most likely to be put to the test in preventing their children from having serious problems with addiction to alcohol and other drugs, especially during their children’s teens and twenties. Families that have little or no history of addiction, and who have children who lack high-risk character traits, usually escape the pain of children who are addicted to intoxicating drugs. Often these families attribute their success to their skillful parenting and other supposed superiorities. Such a happy outcome usually reflects the fact that the family was not put to the test with high-risk children.

Typically, families that have serious addiction problems in their children are not inferior in their functioning, but they have been confronted by difficult problems that many other families have escaped. It ill behooves families that do not have addiction problems to feel superior to families that do have these problems. Confronting problems is a source of strength. The guidelines offered in this chapter can help to reduce the risk of addiction. They cannot eliminate that risk. These guidelines are also helpful to families that do not face addiction by helping the family team function better regardless of the problems it confronts.

Parents, working together if there is more than one parent caring for children, need to define clearly what the family’s expectations are for the children with respect to certain vital behaviors in adolescence. First and foremost, the parents need to deal with the issues of alcohol and other drug use by their children. When, if ever, is the use of alcohol and other drugs permitted? What about the use of tobacco? What are the consequences for violation of the family rules about alcohol and other drugs? How will the rules be enforced? The reasons for the rules, whatever they are, need to be clearly spelled out so that the child knows, from an early age, that the rules are not arbitrary or mean-spirited.

Family rules also need to be defined for other behaviors related to health and safety, including sex. Many other health-related behaviors also should be discussed openly in the family with the clear understanding that the ultimate, personal responsibility for each of them rests with the maturing child. The family rules should be designed not only to make the family function better, but to help the child grow up to be a healthy, productive, reasonably happy, and independent adult living outside the parents’ home. All too often these issues of rules and goals are not discussed within the family. The child is left in the dark about parental expectations until there is a problem, and only then are the “rules” defined, usually in negative terms. That is too late for the good functioning of the family.

Family rules and parental authority are deeply rooted traditions in all cultures. In the last few decades in North America, there has been a potentially dangerous shift of values in many families. There is a lessened parental commitment to putting the children’s welfare first and a matching greater commitment to letting children have their own way running their own lives as they see fit, from young ages.

It is not hard to see where these changes in North American culture have come from. They reflect the general movement toward each person, including children, being more responsible for himself or herself and toward greater immediate personal pleasure rather than delayed gratification. At the same time, behaviors and decisions previously limited to adults have been shifted to children at ever younger ages. These trends in values are characteristic of modern society. North America has been in the forefront of these developments. Although there is much to recommend in some aspects of this change of values—for example, it not only encourages diversity but gives a far larger scope for individual choices—it has a steep downside cost when it comes to addiction because of the specific vulnerability of the selfish brain to the lure of addicting drugs. The price is most often paid by vulnerable youth. Prudent families and communities recognize this risk in modern life and take appropriate actions to remove the choices of addicting drugs from the menu offered to young people. This includes alcohol and tobacco, the use of which is legal for adults but not for youth. We have laws governing these behaviors for youth, but the laws against teenage drinking and smoking continue to be haphazardly enforced and widely flouted. Families need to reassert their authority and to use the current laws against youthful drinking and smoking to support them in these important prevention efforts.

The same prevention guidelines should be used in other social institutions that deal with children and youth. These institutions should review their policies and procedures to ensure that they systematically and routinely reinforce the community-wide values of nonuse of addicting drugs. The most difficult case is the modern college, which has become a breeding ground for alcohol and drug abuse, as vulnerable youth are concentrated in environments that are permissive or even encouraging of drug and alcohol use. Middle schools and high schools are other institutions that need to be clear on these values.

The discussion of prevention in this chapter has focused on family roles in preventing addiction. It has also dealt with the environment in which decisions are made to use or not to use alcohol and other drugs. Typically, drug use of all kinds begins during the teenage years, when the most serious addictions have their onsets. Because the toughest cases of addiction are youth with character disorder who are impulsive and irresponsible and who live in environments that are tolerant about the use of alcohol and other drugs, the guts of any serious addiction prevention program must focus on high-risk youth between the ages of about twelve and sixteen. Education and assistance are vital for these youth. Readers of this book know that the only way that most high-risk youths will be discouraged from the continuing abuse of alcohol and other drugs is if their use is promptly and positively identified, and if that use leads to immediate painful consequences. If young victims of addictive disease are permitted to play out the addicts’ career, they will progress deeper and deeper into addiction as they become older teenagers, with desperately destructive consequences for them, their families, and their communities.

The true test of any serious prevention effort is what it does for high-risk youths. As I make clear in Chapter 12, I am convinced—only reluctantly and only after years of resisting this conclusion—that it will be necessary to develop drug testing programs for high-risk youth that are linked to swift and certain painful consequences if they are to be deterred from full-blown careers of addiction. Addiction, if ignored, is the cultural and biological destiny of high-risk youth today in North America and, increasingly, in all parts of the world. Schools and other social institutions can help, but the primary responsibility for raising a drug-free youth rests squarely on the parents’ shoulders. When it comes to addiction prevention, the central problems in North America today are teenage use of beer and cigarettes. (See Table 9–1 for a checklist for identifying high-risk youth.)

Effective prevention requires information and knowledge. It is important that everyone, especially vulnerable youth, know the hazards of nonmedical drug use and the consequences for violation of the prohibition in their families and in their communities against the use of alcohol and other drugs. Prevention also benefits from loving, supportive human relationships in the family, at school, and in the community. Compassion and respect are essential for prevention of addiction to work over the long haul. There is no reason to be hostile or rejecting of drug abusers, including drug-abusing youth. They need real help. High-risk youth need to be held tightly in their communities to find meaningful support, not to be cast out of their communities. In this way they are like preschoolers having a temper tantrum. They need to be held close so they do not harm themselves by their out-of-control behaviors.

Prevention means not buying into enabling and denial, two central elements of the addictive disease. Enabling is the behavior of those around an addicted person who wittingly or, more often, unwittingly permit the addictive behavior to continue. Parents who hire attorneys to get their alcohol- and drug-using teenage kids out of trouble with the law, and people who call the office to say their spouses are sick when they are actually hung over from drinking are enabling. Denial is to be consciously or unconsciously unaware of the addictive behavior even though the behavior is plainly there. When alcoholics lie about their drinking, and when parents ignore their children’s drug use, this is denial.

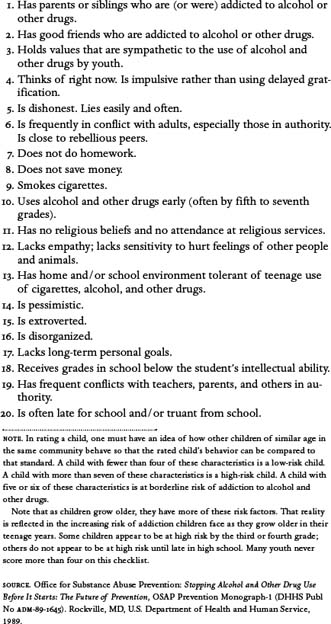

Table 9–1

Identification of high-risk youth.

Prevention requires knowing when youth are using alcohol and other drugs and taking active steps, called interventions, to deal with youthful alcohol and other drug use. Prevention is not simple and not singular. Prevention requires a continuum of responses based on a thoughtful blend of elements into a coherent and comprehensive community-wide effort to stop the use of alcohol and other drugs by youth before it begins, and, failing that, to detect it at an early stage and to intervene decisively to see that it stops. Nothing less fulfills the community’s urgent need to end the tragic modern drug epidemic. Nothing less is worthy of the name prevention.

Effective prevention of addiction has many dimensions, some of which are within the family and some of which are within the youth culture itself. Many productive addiction prevention efforts are best conducted in schools and in other community settings involving youth. Prevention of addiction to alcohol and other drugs means helping young people fulfill their personal destinies, to become all that they can each become to better serve their own long-term interests and the interests of their families and their communities.

This discussion of the environmental approach to the prevention of alcohol and other drug use by youth should not, however, distract from the recognition that the primary defensive line in all high-risk behaviors is the family. No change in the environment can make up fully for failed family performance, and even with terrible environmental situations, strong families committed to antiaddiction values can often raise drug- and alcohol-free children. However, even with both a healthy environment and a strong family taking forceful stands against alcohol and drug use by youth, some high-risk youth will still succumb to the siren call of addicting drugs. Failure to recognize this fact reflects failure to face the power of addiction and the widespread vulnerability to that risk.

In the final analysis, the responsibility for the use or nonuse of addicting drugs falls on the individual. That is why the bedrock of all addiction prevention and all addiction treatment approaches must be personal responsibility. The benefits from getting these issues right are great; the costs of miscalculation are often devastating.

The disease of addiction knows no pity and no generosity. Addiction to alcohol and other drugs is a cruel, relentless, and often devious slave driver. However, by confronting and overcoming this dreadful disease there is a great gift. Families and individuals dealing with addiction can find new and better ways to live as individuals and as families. For most people there is an important spiritual dimension to recovery from addiction. There is often a deeply spiritual dimension to prevention of alcohol and drug problems as well. To say no to drugs, for many people, requires a clear understanding of the purpose of their lives.

The following chapter helps to organize the family when prevention efforts fail and addiction to alcohol and other drugs has to be confronted directly in an addiction-treatment program.

Case Histories

Dan

Dan’s parents appeared to me in family therapy to be almost saints. His father was an enormously successful attorney who worked a prodigious schedule. He was warm, intelligent, and involved with his children. Dan’s mother was a full-time mom who also did volunteer work for their church and in the community while caring for her four children. Dan’s mother’s family was full of alcoholism. One of Dan’s uncles was a sad fellow whose life started with great potential, but who had never worked and who came to live a miserably unsuccessful and unhappy life “in a bottle.”

Dan was mad at his mom for driving “a poor people’s car,” a two-year-old Buick, when “you could afford a Mercedes or a Lexus.” Dan said he was embarrassed by his mother’s car at the same time as he bragged that he lived with the richest family in his school. Dan did poorly in school as a high school senior. He had repeated run-ins with school officials and the police over his use of alcohol and marijuana. Dan and many of his friends lived an expensive, indulgent lifestyle, having every confidence that they would continue to live this way all their lives. In family therapy, it came as a rude shock to Dan that his parents did not plan to underwrite his lifestyle once he left home. He would be expected by his newly determined parents to get into college and maintain at least a B average, taking a full load of courses, or they would not pay for college and he would be asked to live on his own. He had not competed in school for grades or in athletics for many years, although he was smart and athletic. I suggested that much of life was competitive and that he would have to exert himself if he hoped to get a job that would pay for a roof over his head and an ordinary car to drive, never mind a Mercedes or a Lexus.

Dan’s parents had a hard time learning that the more they accepted Dan’s bad behavior, the more bad behavior they got from him. They had struggled to appreciate that there was a lot of “love” in “tough love” so that they could be sympathetic and caring and still be insistent that Dan do his best. Both parents came from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. One of their chief goals in life was to give their children advantages they did not have. Unfortunately, their present success does not guarantee successful futures for their children, and they have given their children a painful handicap that is common among the affluent. An indulgent lifestyle stifles rather than fosters hard work. Most families I see like Dan’s family find ways to manage this problem reasonably well, but it is rare to see children of affluence who are able to perform at the level of their successful parents, especially if the affluence has come to the family before the children reached late teenage years.

Maria

Maria announced at a meeting of Narcotics Anonymous, “This is my first meeting in this town. I’m from Charlotte, North Carolina. I moved up here to finish college. I had to leave Charlotte because the drugs and alcohol were so bad in my school, and I had a horrible time with my own use. I worked the NA program, and I got my life back under control.

“You can already guess what happened next. When I got to my new school, my roommates were both addicts, of course. Is everyone addicted, or is it just my bad luck? Anyway, I procrastinate about everything, so I procrastinated for three months after I got to town before I came to an NA meeting here. I was hoping, I guess, that I might not need to go to meetings, since I have so much studying to do as a premed student.

“But tonight one roommate was passed out by 6 p.m., and the other one has friends over to smoke dope. I just couldn’t take it any more. The worst part was that I almost used drugs again with that stuff all around. So here I am. I feel at home already even though I don’t know any of you. Can I get some names and phone numbers after the meeting?”

Children’s positions in life will be determined by their own achievements, not by the achievements of their parents. For poor children, this simple, timeless fact can be a relief. For rich children, growing up can be terrifying. For children from all parts of the economic spectrum, this fact must be faced directly as a great opportunity, one that they need not face alone if they will simply reach out to others, both inside and outside of their families, who can help them with this incredible transition. There is one more truth that is seldom spoken to young people who are growing up and getting ready to go out on their own: life is scored on one’s actual performance and not on one’s ability. This simple truth can be disturbing to children who have been told for years, “Don’t worry about your grades. You are a smart person with lots of ability.”