Common Snapping Turtle

(Chelydra)

The common snapping turtle is sometimes further divided into two subspecies: the northern snapping turtle (C. serpentina serpentina) and the Florida snapping turtle (C. serpentina osceola). Two other species of snapping turtles live in Central and South America.

Common snapping turtles can be identified by sawtooth ridges on the upper shell, a very large head and neck, and a long, ridged tail. With age, the ridges become smoother.

Description

The carapace, or upper shell, of the common snapping turtle can variously be green, tan, or brown to black, with rough scales on the top and saw-toothed edges toward the back. The plastron, or lower shell, is too narrow and small to allow the turtle to pull its legs, tail, and head into the shell space. The yellowish legs are sturdy and thick. The yellowish tail is almost as long as the shell with saw-toothed ridges along the top. The large, dark-colored head has powerful jaws.

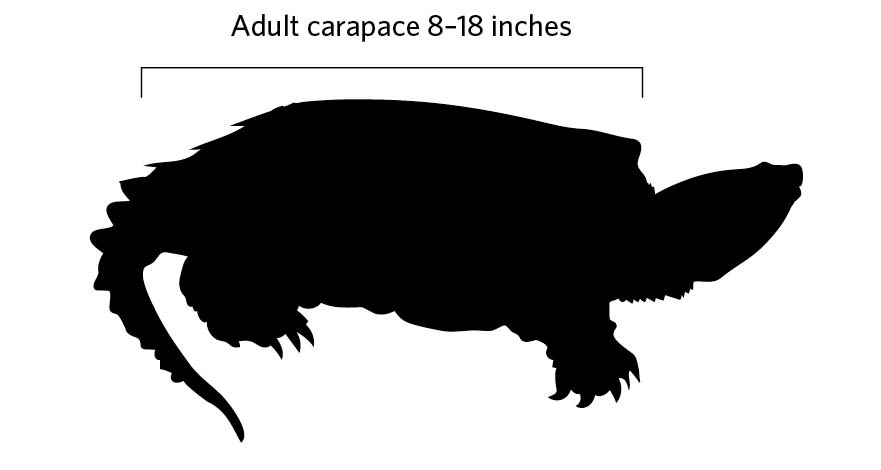

Turtles are measured by the straight carapace length from the front to the back of the shell. The common snapping turtle varies from 8 to 18 inches in length, with weights of 10 to 35 pounds. Males are larger than females.

▲ Common Snapping Turtle

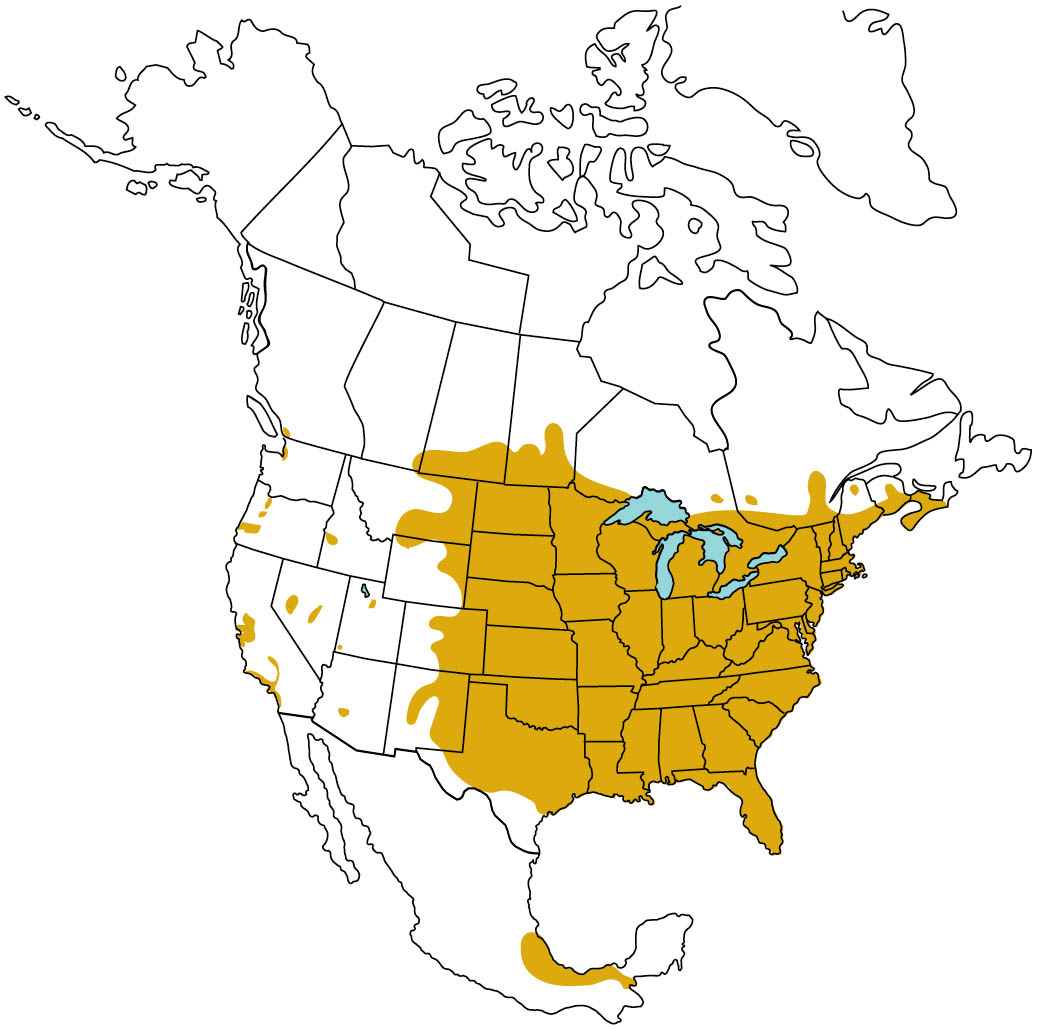

Common snapping turtles were originally confined to an area across the continent to the eastern edge of the Rocky Mountains, northward into southeastern Canada up to Nova Scotia, and south to the Gulf of Mexico. As an introduced, invasive species, they are now found in all the continental states.

Habitat and Behavior

Common snapping turtles prefer freshwater wetland environments with vegetation and muddy bottoms such as ponds, lakes, swamps, marshland, or slow-moving rivers and streams. In Florida they can be found in brackish water as well. In areas of colder water, snappers will bask in the sun but not as often as other turtles. In shallow water, they often lie in ambush with only their snout exposed.

Opportunistic omnivores, snappers consume aquatic vegetation, fish, amphibians, crustaceans, insects, reptiles, waterfowl, small mammals, and carrion. Once the water temperature becomes colder, snappers stop feeding and settle to hibernate in depths of 12 to 39 inches, buried in sand or mud with only their eyes and snout exposed.

Snappers lead solitary lives except during mating, which occurs about 6 weeks before the female lays one clutch of 26 to 55 eggs. In the warmer southern states, egg laying occurs from mid-May to mid-June, and in northern areas about a month later. A female can travel as much as 9 miles in search of sandy areas with little vegetation and good sun exposure, traveling about 165 yards in a day. She then scrapes out a shallow hole for her eggs, and hatching occurs from late summer to early fall depending on incubation temperature. This is when farmers and homeowners see snappers out of their usual environment.

Females mature at as early as 12 years old in warmer areas or as late as 20 years. They may live over 100 years. Large predators such as alligators and bears will prey on mature snappers, and many smaller predators, birds, snakes, and large fish eat juveniles.

Alligator Snapping Turtle

(Macrochelys)

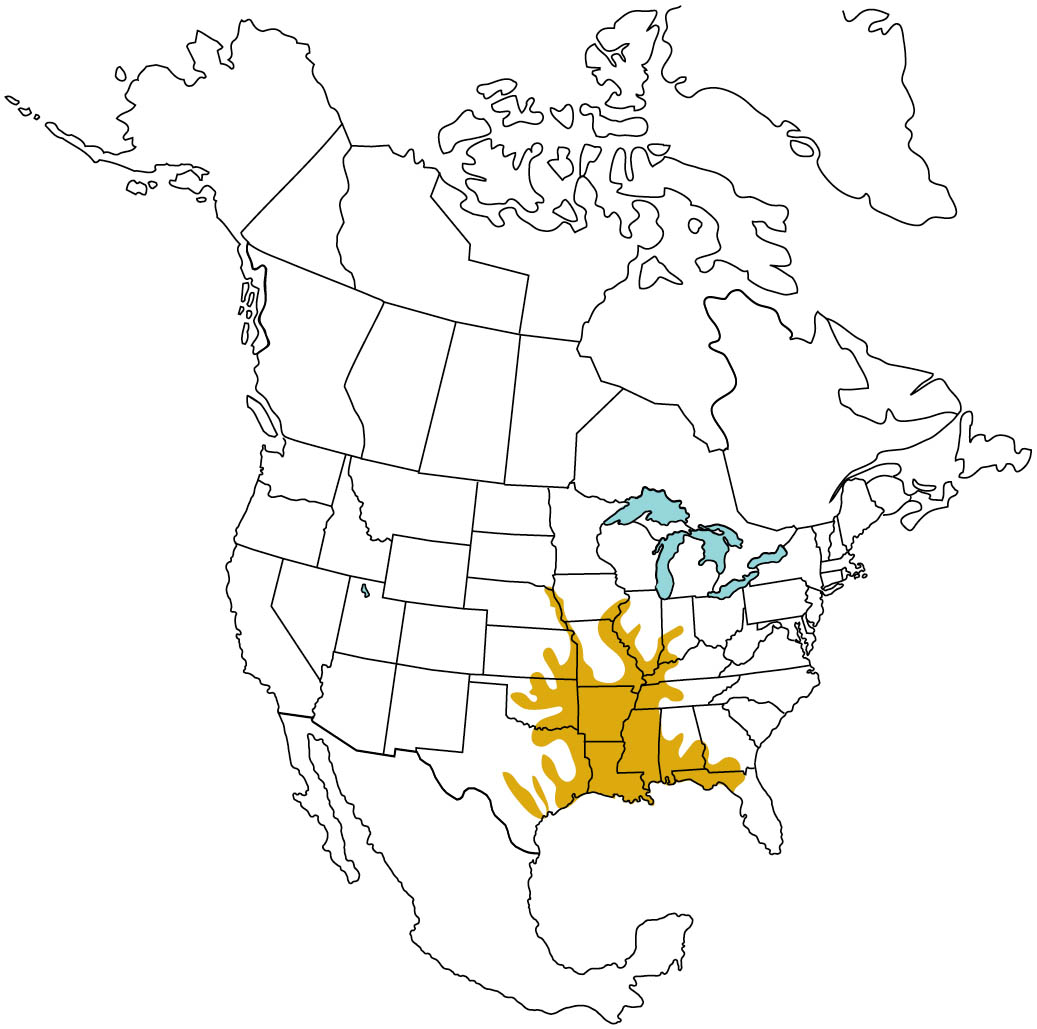

Compared with the common snapper, the alligator snapping turtle has a small range. Some experts divide the Macrochelys into 3 separate species: the Apalachicola (M. apalachicolae), the Suwannee (M. suwanniensis), and the alligator snapper (M. temmincki).

The alligator snapper has a triangular, pointed head. When its mouth is open, the fleshy vermiform lure is visible.

Description

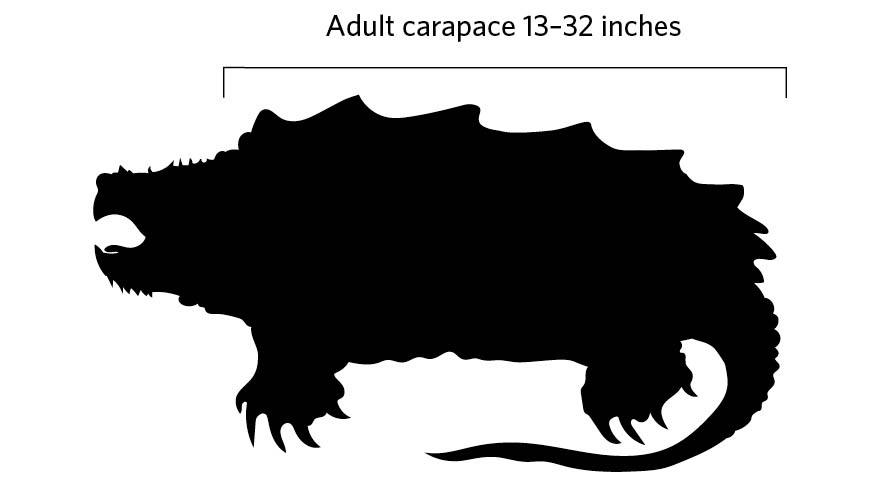

One of the heaviest freshwater turtles in the world, the alligator snapper ranges from 13 to 32 inches long and weighs from 8 to 250 pounds, though averaging 30 to 50 pounds. It is easily identifiable by 3 large, pointed ridges along the top of the carapace and spikes or serrations along the edges of the shell. Shell color can be solid brown, black, gray, or olive green. The jaws are powerful, the head large, heavy, and distinctive with the eyes on the sides. The alligator snapper’s relatively shorter neck can make it easier to handle than the common snapper, but it is still potentially very dangerous.

Habitat and Behavior

Adult alligator snappers tend to be found submerged in deeper water of lakes, river, canals, and swamps. Young turtles often live in smaller streams or ponds. Both active hunters and scavengers, these snappers eat fish primarily but also a wide range of animals, fish carcasses, carrion, and some plant life. During the day they lie in ambush, mouth open, and do more active hunting at night. Inside its mouth, the alligator snapper has a pink vermiform, or worm-shaped, appendage on the tip of the tongue, used to lure fish.

Alligator snappers mature at about 12 years of age, surviving up to 45 years and sometimes quite a bit longer. They mate in early to late spring, emerging on open land only to lay 8 to 52 eggs. About 2 months later, the female digs a nest about 160 feet from water. Hatching occurs in fall and is dependent on incubation temperature.

▲ Alligator Snapping Turtle

Alligator snapping turtles are generally found in the river systems of the Mississippi River basin, the Gulf States, and Texas, and as far north as Indiana, Illinois, Kansas, and Missouri.

Human Interactions

Snapping turtles will opportunistically prey on waterfowl, including ducks and geese, and occasionally other poultry or small animals or pets.