By the 1930s, the three large North American predators — wolves, mountain lions, and grizzly bears — were nearly eliminated from the continental United States.

When European explorers and colonists arrived in the Americas, the single word they most often used to describe the “new world” they encountered was abundance — an abundance of land, natural resources, and animal life.

Of course, they weren’t the first to discover the New World, because native peoples had long occupied and used the land, plants, and animals, trading commodities among one another. They altered the landscape, created agricultural fields, burned grasslands and forests to keep them open for grazing for favored herbivores, and may have been responsible for overhunting the megafauna after the last Ice Age.

Following that post–Ice Age era, some cultures became nomadic hunter-gatherers while others formed permanent communities for fishing or farming. Living more sustainably with nature, native peoples generally met their resource needs without the destruction of diversity and balance that lay on the horizon.

European settlement would usher in an era of reckless exploitation that, from our contemporary viewpoint, was a truly stunning destruction of wildlife. The Merriam’s elk, passenger pigeon, Carolina parakeet, and Labrador duck all went extinct due to relentless hunting. It was an extremely close call for the American bison, reduced from a population of 60 million to just 300 animals by 1900. Herons and egrets died by the thousands, primarily for plumes to decorate ladies’ hats. Even the white-tailed deer became exceedingly rare in the eastern United States due to human activities. Animals were killed for their fur, hide, or feathers, but none of those was the primary reason that the large predators were destroyed.

The reason was that these animals were regarded as dangerous. As their natural prey was decimated, they became an increasing threat to the colonists’ livestock. England, Scotland, Ireland, and other European homelands of the colonists had been eradicating wolves and other large predators for centuries. Since these animals were already extinct in the United Kingdom, livestock raisers there had no need to protect their livestock from large or even medium-sized predators. With their only predator being the fox, which was widely hunted on foot and on horseback, sheep were turned loose to graze without active shepherding or livestock guardian dogs (LGDs). There was no tradition of protecting sheep or cattle from serious predation.

It is therefore not surprising that the wolves, bears, and mountain lions of the eastern colonies seemed terrifying. Taming nature was the first order of business. The first wolf bounty was set in 1630 in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. From that point forward, the colonies and later the states set bounties for killing the large predators. Thus the hunting, trapping, and poisoning commenced.

By 1870, no mountain lions remained in the eastern states or provinces. By the beginning of the 20th century, wolves were gone from the continental United States and the adjoining areas of Canada except the northernmost Great Lakes region and northern and western Canada. By the 1930s, wolves, mountain lions, and grizzly bears were nearly eliminated from the Intermountain West, except for isolated pockets.

The loss of the large predators and the changing landscape allowed the opportunistic coyote, originally a resident of the Great Plains and arid West, to expand its territory throughout the continent. The widespread coyote is now the single greatest threat to livestock and poultry raisers. The loss of large predators also allowed small predators — raccoons, opossums, and skunks — to increase in numbers and to expand their ranges as well.

By the 1930s, the three large North American predators — wolves, mountain lions, and grizzly bears — were nearly eliminated from the continental United States.

While the destruction proceeded, the foundations of the conservation movement were also being laid. The 19th century saw the origin of a number of progressive movements — to abolish slavery, fight for women’s rights, establish laws regarding child labor and food and drug safety, and regulate animal welfare. Alongside this progressivism, the love of nature grew. With it came efforts to preserve and protect lands, animals, and natural resources. As the cities became increasingly crowded, people grew to value parks and recreation land for camping, hiking, and bird watching. Sympathy and empathy grew for wild animals.

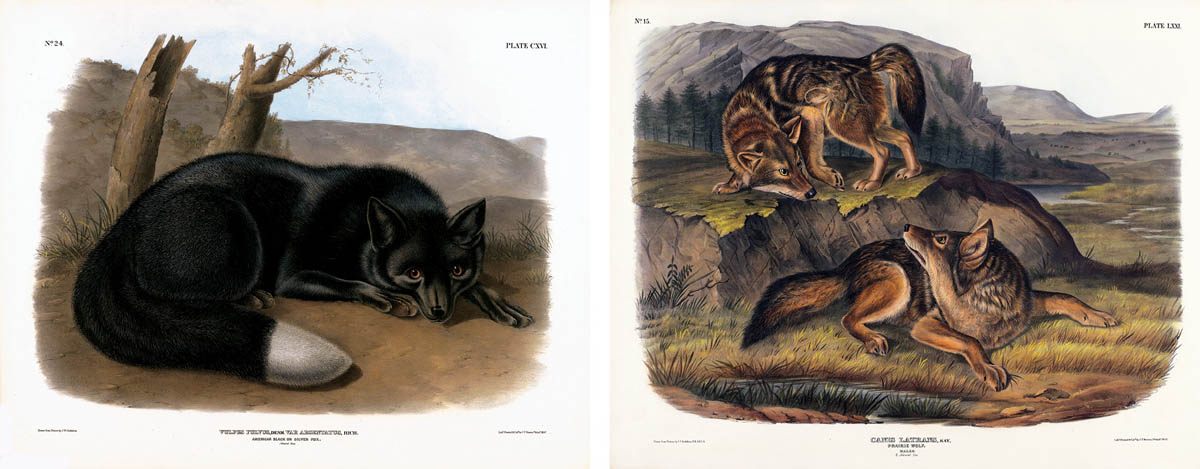

This renaissance was fostered by a number of famous writers, artists, and naturalists. Some were both conservationists and hunters, which was not a contradiction. Others were explorers of the wilderness, writing and making images to reveal its natural beauty. Among the first and foremost was John James Audubon, an artist, naturalist, and the most famous ornithologist of his time. Other artists included George Catlin, Thomas Moran, Albert Bierstadt, and Frederic Edwin Church. John Burroughs, Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, John Muir, William Cullen Bryant, George Perkins March, Ernest Thompson Seton, and Theodore Roosevelt wrote about nature and wild animals. Theodore Roosevelt and the writer and naturalist George Bird Grinnell, founder of the Audubon Society (1905), could be considered the earliest conservationists.

John James Audubon’s illustrations brought viewers face-to-face with wild animals in their own element.

In 1860, 80 percent of the US population still lived in rural areas, but the march toward urban development was proceeding. As Frederick Law Olmsted designed New York City’s Central Park, efforts were beginning in the states to preserve land in the Adirondack and Catskill Mountains. Soon after biologist Ernst Haeckel first used the word ecology, John Wesley Powell, back from his exploration of the Colorado River, expressed the importance of recognizing the environmental fragility of the West. The world’s first national park — Yellowstone — was established in 1872. By this time, the concept of conservation implied management of natural resources and public lands for human use, encompassing the forests, grazing land, minerals, water, fish, birds, and other animals. Sustainable and responsible use of this land was essential to conservation.

The turn of the century saw the election of Theodore Roosevelt as president. A lover of hunting and the hunting lifestyle, he worked for the conservation of game species and the environment they needed. Hunters such as Roosevelt believed it was not sporting to kill predator species. Predators should be killed only to maintain game animals and birds for hunting. Roosevelt and fellow conservationists such as Gifford Pinchot worked to create and protect national forests, wildlife refuges, and parks.

At the same time, the separate concept of preservation was taking root. John Muir founded the Sierra Club in 1892 with the mission to preserve and protect wilderness. Preservationists wanted humans to value wild land and animals solely for their natural beauty and not their usefulness to humans. One of the earliest conflicts between these two points of view was the conservationists’ proposed dam in the Hetch Hetchy Valley of Yosemite National Park. Flooding the valley created a huge water supply for San Francisco, while also destroying the beauty and life found in the valley. From that point on, tension and conflicting priorities increased between conservationists and preservationists.

While conservation and preservation were gaining ground, predator control efforts continued. The National Animal Control Act for the destruction or control of predators was passed in 1931 (although Congress had already been providing funds for wolf and coyote control during the preceding 15 years). Famed conservationist Aldo Leopold developed game management science in the model of forestry science. By the 1940s, he became deeply concerned that the burgeoning population of deer and elk, no longer controlled by predators, was threatening the environment.

In the 1930s, in the days of the Dust Bowl, evidence mounted that unregulated land use was destructive. The Taylor Grazing Act was passed to “stop injury to the public lands by preventing over-grazing and soil deterioration.” In 1946, the Bureau of Land Management, now in the Department of the Interior, replaced the earlier Grazing Service. Early water and air pollution acts laid the groundwork for future ecological regulation. In 1949, Aldo Leopold wrote A Sand Country Almanac, which is widely regarded as one of most influential environmental books of the 20th century. By 1951, the Nature Conservancy was founded, an organization that would come to own and manage the largest collection of private nature reserves in world.

“Wilderness is not only a haven for native plants and animals but it is also a refuge from society. It is a place to go to hear the wind and little else, see the stars and the galaxies, smell the pine trees, feel the cold water, touch the sky and the ground at the same time, listen to coyotes, eat the fresh snow, walk across the desert sands, and realize why it’s good to go outside of the city and the suburbs.”

— John Muir, 1901

“We reached the old wolf in time to watch a fierce green fire dying in her eyes. I realized then, and have known ever since, that there was something new to me in those eyes — something known only to her and to the mountain. I was young then, and full of trigger-itch; I thought that because fewer wolves meant more deer, that no wolves would mean hunters’ paradise. But after seeing the green fire die, I sensed that neither the wolf nor the mountain agreed with such a view. . . .

“I now suspect that just as a deer herd lives in mortal fear of its wolves, so does a mountain live in mortal fear of its deer. And perhaps with better cause, for while a buck pulled down by wolves can be replaced in two or three years, a range pulled down by too many deer may fail of replacement in as many decades. So also with cows. The cowman who cleans his range of wolves does not realize that he is taking over the wolf’s job of trimming the herd to fit the range. He has not learned to think like a mountain. Hence we have dustbowls, and rivers washing the future into the sea.”

— Aldo Leopold, 1949

In the 1960s, growing concerns and serious problems came to the fore with a resulting flurry of government action. Just as the photography of Ansel Adams was capturing the ethereal beauty of nature, two important writers captured the crisis the country faced. Both Rachel Carson, who wrote Silent Spring in 1962, and Stewart Udall, with The Quiet Crisis in 1963, brought widespread public awareness to a broad and deepening environmental situation.

As secretary of the interior, Udall championed a series of important pieces of conservation legislation: the Wilderness Act, the Endangered Species Preservation Act (later expanded as the Endangered Species Act), the National Trails Act, and the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. Other important environmental efforts included the National Environmental Quality Act, the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts, and the Environmental Policy Act. The United States became the first nation to pursue far-reaching environmental conservation efforts. In 1992, the Convention of Biological Diversity convened in Rio de Janeiro as part of the Rio Earth Summit and gathered worldwide resolve to promote sustainable development for the needs of people, animals, and plants; in 2002, Environment and Climate Change Canada enacted the Species at Risk Act of Canada (SARA) to protect wildlife. In this book, when the terms Endangered and Threatened are capitalized, they refer to species listed under the Endangered Species Act (https://www.fws.gov/endangered/species/us-species.html).

Among the very first animals listed by the US government as Endangered species were the gray wolf, the Florida panther, and the grizzly bear. For the first time, predators were offered official protection. With this move, the philosophies and methods of preservation and conservation began to come together in a new approach.

First presented as a concept in 1978, conservation biology is the scientific study of nature and biodiversity in order to preserve species, habitats, and ecosystems. Conservation biology seeks to bring together ecology, which studies organisms and their environment, and conservation, in both policy and practice. It recognizes the importance of carnivores in helping to maintain biodiversity, keep prey species healthy, and hold their numbers in balance.

A keystone species, even though small in number, may have a large effect on the environment.

The apex predator sits at the top of the food chain. An adult apex predator is not prey for other animals except humans, who are also an apex predator.

Habituation is an adaptive behavior in which the predator grows used to human presence and stops responding appropriately to it, leading to potentially dangerous interactions.

Fragmentation occurs when populations of a given species are geographically separated by human development.

A wildlife corridor is a connecting area between habitats to foster genetic diversity among individuals in a species that may have become fragmented.

Rewilding is conservation on a large scale, including protecting or reintroducing apex predators or other keystone species, restoring and protecting wilderness and habitat, and providing corridors to promote genetic diversity.

BLM Bureau of Land Management

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CITES Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

COSEWIC Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada

DNR Department of Natural Resources (for individual states)

ESA Endangered Species Act

FWS US Fish and Wildlife Service (manages fish, wildlife, and natural habitats; enforces federal wildlife laws; protects endangered species; conserves and restores wildlife habitat)

IUCN International Union for Conservation of Nature

SARA Species at Risk Act of Canada

USDA US Department of Agriculture

USFS US Forest Service

Predation on domestic animals isn’t the only danger from proximity to wild animals. Besides the contamination of crops and feedstuffs by smaller predators, various diseases can be passed from animals to humans, caused by bacteria, parasites, or viruses. These zoonotic diseases can have serious or fatal consequences. Water can become contaminated with giardia, leptospirosis, or salmonella, and dogs, cats, and other livestock can acquire these diseases from drinking it.

Raccoons remain the most frequently reported rabid wildlife, followed by bats, skunks, and foxes. Detailed information, by state, is available on the CDC website for both domestic and wildlife rabies cases.

Wild animals are responsible for 92 percent of all reported rabies cases in the United States and Canada; domestic animals account for the rest. In both countries the primary carriers are raccoons, bats, skunks, foxes, and, less often, coyotes — and the most common carrier varies by state or province. Rodents and rabbits rarely contract rabies, and opossums are rabies resistant. After an encounter, an increasing number of people take postexposure treatment. Only 1 to 3 fatal cases of rabies occur in humans each year in the United States, however, and the disease is even rarer in Canada. Most fatalities occur because the individuals did not know they were exposed or failed to receive appropriate and timely treatment.

Rabies is a viral disease affecting the central nervous system. The virus is transmitted through the saliva of an infected animal, usually by a bite, exposure to an open wound, or contact with mucous membranes. If your dog or another animal has encountered or fought with a potentially rabid animal, use extra caution to avoid coming into contact with any fresh saliva on its coat. The virus cannot survive after the saliva has completely dried. Wear protective gloves if you bathe your dog after an encounter.

Symptoms. Rabies in wild animals can include one or more symptoms: agitation, biting or snapping and drooling, unnatural tameness or lack of fear, loss of coordination, wobbly or circling behavior, paralysis, disorientation, self-mutilation, or daytime activity in a nocturnal animal.

Treatment. Medical attention is essential for all wild animal bites to humans, pets, and livestock. Before seeking emergency treatment for a bite from a potentially rabid animal, immediately and thoroughly scrub the wound with antiseptic soap or Betadine and rinse extensively. Treatment, when received in a timely manner, is 100 percent effective. All dogs and cats that come in contact with wildlife should be vaccinated against rabies as a preventive. Contact the authorities if you capture or suspect a rabid animal.

In addition to rabies, other serious zoonotic diseases include the following:

For more information on these diseases and others, contact the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention at cdc.gov/healthypets/pets/wildlife.html.

Although any mammal may be infected with rabies, some carnivore species are major reservoirs for the virus in distinct variants. Bats may also serve as rabies reservoirs.

For many reasons, we must learn about predators and their habits and behaviors, how to identify them, and how to prevent damage. Ultimately, we must learn to coexist in the world we share, understanding the value and place of predators in the ecosystem. Some predators actually do pose a threat to people, although a small one. We may have forgotten how to live with predators around our homes and wild places, so we must learn how to avoid risky behaviors, reduce attractants, and be proactive in preventive techniques and strategies.

The bottom line: We don’t need to fear predators, but we do need to learn how to deal with them — whether in our chicken coops, our pastures, or our own backyards.