Chapter 4

Cats

Felidae

Traditionally, the 40 species of cats or felines were divided into roaring and purring cats, regardless of differences in size.

The roaring Panthera group included the African lion, the leopard, the jaguar, and the tiger. The cats of the Felis group purred or made other sounds and included the small house cat (Felis catus), the lynx, the bobcat, the ocelot, the caracal, the jaguarundi, and the larger mountain lion. The cheetah and the clouded leopard stood alone in their own individual groups.

More recently, genetic studies have suggested that three separate lines of cats evolved from common ancestors: the small South American cats; the domestic Felis catus and other related cats; and the remaining large cats, including the lion, tiger, mountain lion, lynx, and bobcat.

What we do know is how similar the worldwide members of the cat family are to one another. Only the polar regions, Australasia, and Oceania have no native cats, although the domestic cat has been taken nearly everywhere. Cats resemble one another not only in appearance but also in their abilities and behaviors. Athletic and powerful, they are good climbers, and many are excellent swimmers. They have adapted to a wide variety of environments, and most display camouflage coloration. Cats are solitary, territorial, and polygamous, except for the sociable lions, which cooperatively raise their cubs.

The big cats are specialized carnivores, often apex predators near the top of the food chain and keystone species in their habitat. Capable of killing prey much larger than themselves, cats have long, conical canine teeth used for puncturing their prey and severing the spinal cord or killing by suffocation. All cat species except the cheetah have retractable claws.

Large eyes and excellent vision allow cats to hunt during the day or night. They both stalk and ambush prey, and they are fast sprinters but lack the endurance to chase prey over long distance. They have erect, movable ears, excellent hearing, and a good sense of smell. The rough tongue helps remove tissue from bones.

The cat’s inborn hunting instincts — not a bloodthirsty nature — can result in surplus killing of more prey than it can eat. This instinct is not usually triggered in the wild, unlike the situation of enclosed captive domestic stock or poultry.

Many cats are perceived as dangerous animals and have been hunted extensively — out of fear, for sport, and often for their beautiful pelts. Habitat loss and human development remain great challenges to the survival of many feline species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists 29 of the 40 cat species as in decline, some critically endangered. In the United States, the jaguar, jaguarundi, ocelot, Florida panther, mountain lion, and Canada lynx are considered threatened.

Mountain Lion (Puma concolor cougar)

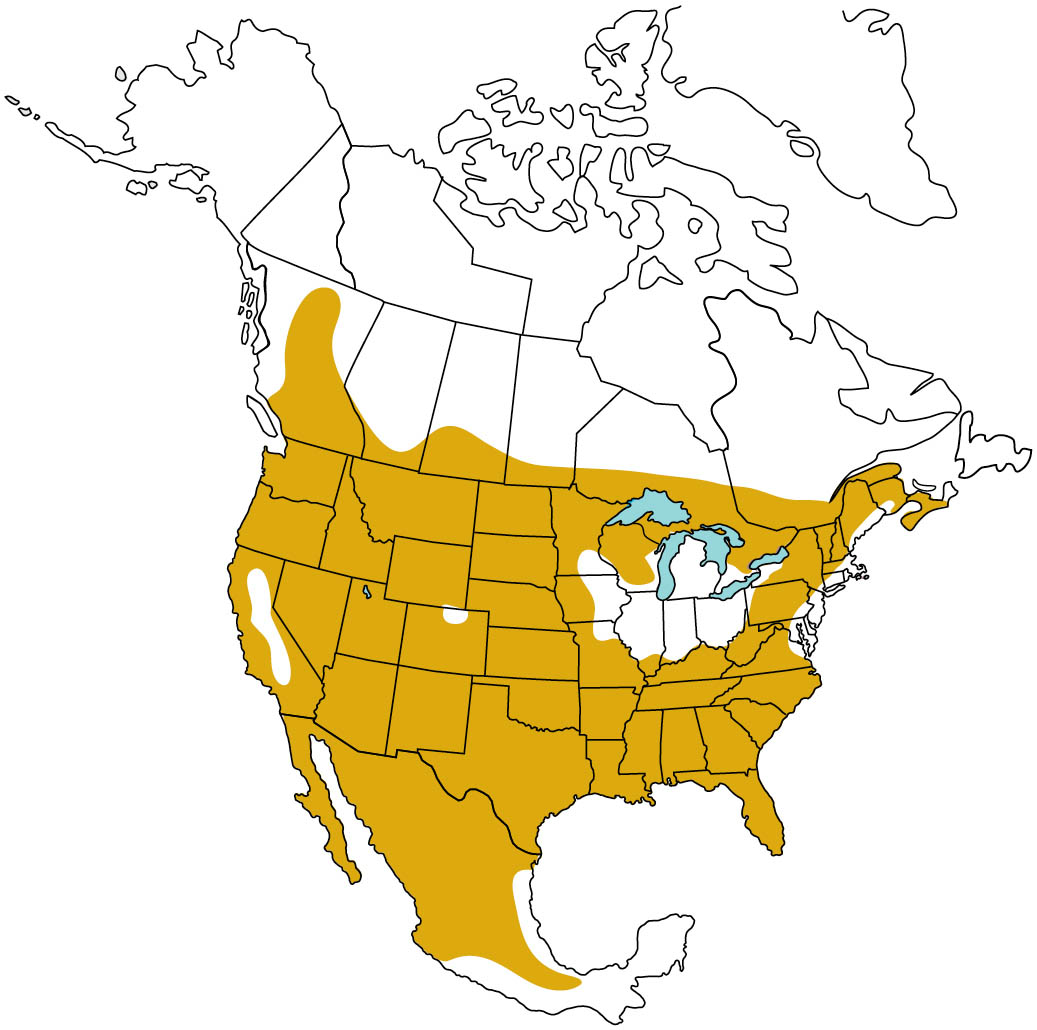

Mountain lions once roamed throughout the Western Hemisphere from the Yukon in northern Canada to the southern Andes Mountains in Chile. They were found in virtually every type of terrain, from high mountain forests to deserts to tropical wetlands. The mountain lion was present nearly everywhere in the lower 48 states.

With this widespread presence, the big cat came to have more names than any other animal on earth — including cougar, puma, catamount, mountain lion, and panther. From Mexico southward it is still called by its Spanish names leopardo and el leon; indeed, Vespucci, Columbus, and Cabeza de Vaca all mentioned the “lions” they discovered in the New World.

For some time, European fur traders believed they were seeing only female lion pelts and that the larger males were hiding somewhere deep in the forests or mountains. Later it was widely believed that mountain lions were a light-colored African or Asian leopard or panther. In the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida, it was often called tyger. Catamount or cat of the mountains was used from New England down the eastern coast. Panther and painter are still used in the southeastern states, although the mountain lion is definitely not a panther. In 1774, the famed naturalist Comte de Buffon first recorded the name cougar, probably evolved from Portuguese based on native Guarani, and puma itself was not used until 1858. Biologists finally settled on the name Puma concolor, or “one color.”

Used as early as 1777, puma is a Spanish word and originated with a native Quechua word meaning “powerful.” The Cherokee klandagi meant “lord of the forest,” and the Chickasaw keo-ishto described the “cat of the gods.”

The “lord of the forest” reigned over the continent before the arrival of the Europeans. Many native peoples respected the big cat and viewed it as sacred, but the new colonists saw it primarily as a threat to livestock and game. Although they were familiar with wolves, mountain lions seemed exotic and dangerous. From the earliest days of settlement, local bounties were paid for killing mountain lions, and they were purposefully eradicated in many eastern states. As cattle and sheep moved onto the Great Plains, the federal government enacted predator control efforts based on hunting or trapping. Across the continent, development, habitat loss, and prey loss had a major impact on mountain lions; they need large home territories and the availability of their favored prey.

Once roaming the largest range of any land mammal in the Western Hemisphere, the mountain lion was gone from the eastern United States and Canada by the beginning of the 20th century, except for the very small population of Florida panthers. The Eastern mountain lion is officially regarded as extinct, although occasional sightings now occur in its old home grounds. Throughout the Western Hemisphere, the mountain lion now occupies about half of its former range. The species is protected in much of Central and South America.

Recent genetic research suggests the North American mountain lion is one subspecies, with five separate subspecies in South America. The cheetah, the jaguarundi, and the mountain lion are also genetically related. The mountain lion and jaguarundi may be descended from a common ancestor that first migrated into the Western Hemisphere some 8 million years ago. The modern North American subspecies itself may be descended from a small group that survived beginning about 10,000 years ago.

Today the mountain lion is reliably found in 12 western states, Alberta, and British Columbia, and its range is expanding. The population is estimated at about 30,000, although the actual numbers are in dispute. Mountain lions are hunted as game animals in some states and protected in others.

Solitary and reclusive, mountain lions are rarely observed even where their population is large, but their presence is becoming more evident in suburban and recreational areas and they remain a predator threat to livestock raisers. Humans and mountain lions are coming into increasing conflict, as development increases and subsequently fragments or isolates mountain lion territory. Lethal control has lessened in some areas, large-prey numbers have increased, and mountain lions are attempting to expand their range. Mountain lions may also become dangerously habituated to humans, necessitating their removal.

These big cats remind us of the power and beauty of nature. Balancing ecological needs and mountain lion management with human interactions, hunters, and livestock raisers will continue to be challenging.

Florida Panther

The mountain lion in Florida has long been called panther and it reigns as the state animal. Although it was once considered a separate subspecies, P. concolor coryi, recent research placed the North American mountain lions together as one subspecies. This change did not affect the status of the Florida panther population, which is protected as an Endangered species. In 2013, the population of wild Florida panthers was estimated at 160, an increase from the 1970s, when only 20 to 30 panthers survived in the wild.

From its formerly widespread range in the southern states, the Florida panther now occupies only a fraction of that territory in 16 Florida counties, including the Everglades National Park, the Big Cypress National Preserve, and the Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge. In this relatively small area, the population became fragmented and isolated, resulting in low genetic diversity. Eight female mountain lions from Texas were introduced into the Florida population in 1995. Although only 5 cats survived to produce offspring, the experiment was judged a success.

Threats to conservation include habitat loss due to development and traffic-related accidents. Florida panthers are also preyed upon by alligators and injured in territorial fights between the big cats.

Description

The mountain lion has excellent vision, hearing, and smell. It does not roar like the jaguar but can scream, purr, growl, and hiss. It can climb with great agility, jump as high as 15 feet, bound or leap as far as 25 feet, and sprint up to 50 mph. Although the mountain lion will cross a river, it generally avoids swimming.

Long and lean, females and males appear physically identical, making it very difficult to tell them apart. The strong legs have large paws equipped with retractable claws. The hind legs are longer than the front legs.

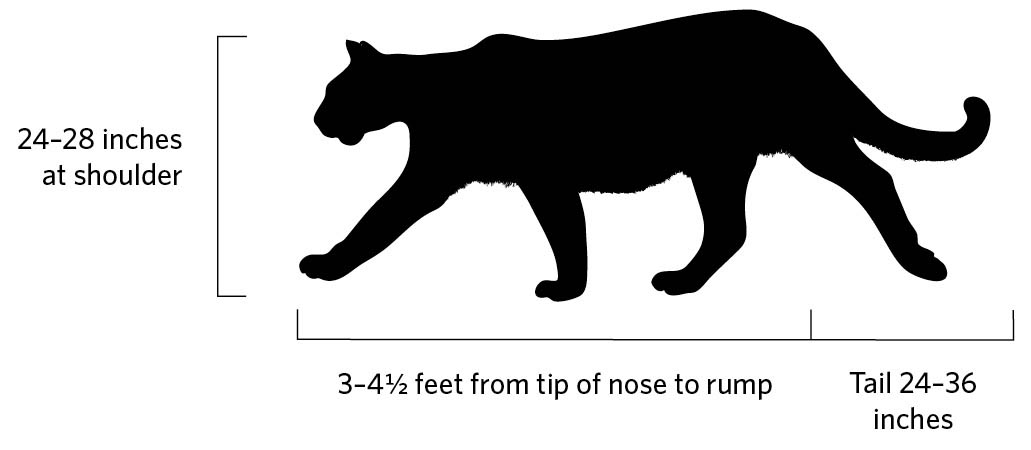

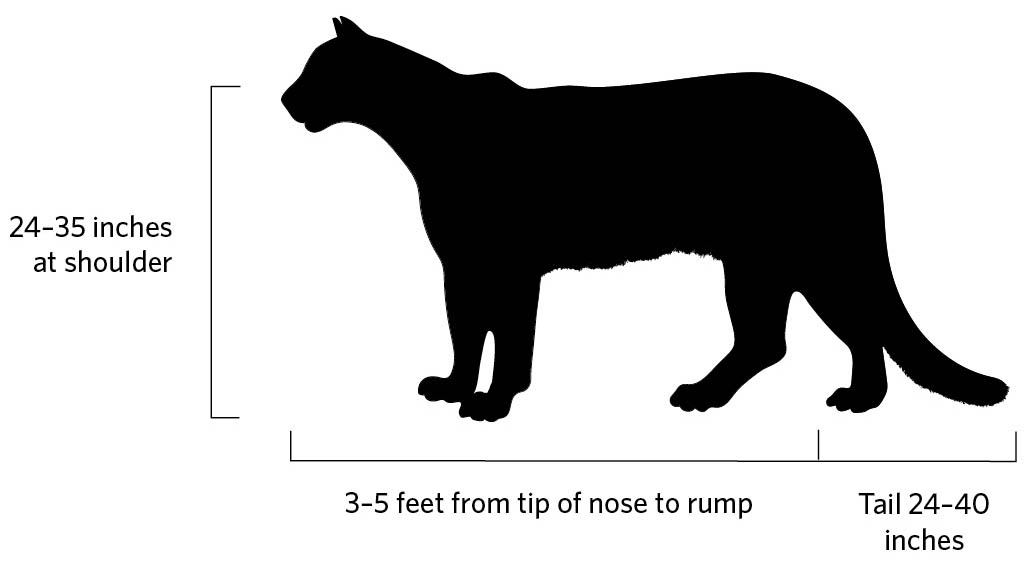

Size. Males are significantly heavier than females. Adult males typically weigh 130 to 150 pounds or more, and females weigh 85 to 120 pounds. Although more uncommon, larger mountain lions have been recorded at 190 to 210 pounds. The head and body are 3 to 5 feet in length, with a long tail of 24 to 40 inches. Adult males can have an overall length of 6 to 8 feet, including the tail. Standing 24 to 35 inches tall, mountain lions have a relatively small, rounded head with small, rounded ears.

Coat and coloration. Mountain lions are uniformly colored, either in shades of buff to tawny to red or silvery to bluish to slate gray. Different colors can occur in the same litter. An all-black color does not exist in the mountain lion population. The lips, chin, throat, and belly are lighter, with blackish tints on the muzzle, the rounded ears, and the tail tip.

Habitat and Behavior

Mountain lions are adapted to a range of habitats in North America, including open forests, brushy or rocky areas, canyons, wooded swamps, and grassland. In any habitat, mountain lions require sufficient cover and prey, but they will cross open, flat, and exposed spaces such as agricultural fields when necessary.

The territory or home range of a male mountain lion varies from 10 to 500 square miles, averaging 50 to 150 square miles. Size is related to prey availability and terrain. The male’s territory may overlap the ranges of 2 or more females (which will be half the size of his), but not with those of other males. Female ranges may overlap one another as well, and females tend to raise their litters within the male’s territory. Territories are marked with feces and urine-soaked debris or dirt piles, 4 to 6 inches high, often left near claw-marked trees.

Hunting and foraging. Both males and females without kits live solitary lives. They are primarily nocturnal, although most activity is at dawn and dusk. They can be active during the day in more remote areas or where they become habituated to human presence. Hunting mountain lions may travel many miles every night. They tend to cross dirt trails and roads rather than follow them, but they will use dry washes and trails to move between areas of their range or in search of new territory. During the day, mountain lions use many different resting sites rather than an established den, often moving on every night.

Silently stalking or ambushing its prey, the big cat will leap onto the animal’s back and bite the base of its skull to break its neck. An adult makes a major kill about every 2 weeks, although scavenging birds and other predators are attracted to the kills, which may then force the cat to hunt again sooner. Mountain lions often drag the carcass to a cache site, covering it with debris. They return several times to feed and move the cache, usually at night. They often sleep near the carcass to guard it, although males may leave to patrol their territory.

Mountain lions clearly prefer deer and other large ungulates (elk, caribou, pronghorn, moose, wild sheep, and mountain goats) and can hunt animals much larger than themselves. Ungulates form from 70 to 90 percent of their diet, depending on location. Less often, mountain lions hunt smaller mammals and predators, including coyotes and bobcats. Mountain lions will also make use of the smallest mammals, birds, fish, or even insects and will also attack domestic equines, cattle, sheep, goats, pigs, rabbits, or poultry. They rarely scavenge carcasses. The Florida panther often hunts feral hogs and armadillos, while western coastal mountain lions will consume sea mammals.

Life Cycle

Breeding is possible year-round, although in colder climates mountain lion kittens are more commonly born in spring and summer. Both sexes will yowl and wail at night to attract mates, and males will warn off other males. Mountain lions are probably polygamous breeders, and the female raises the litter alone. She uses caves, ledges, or dense cover for the initial period of intense care, but then moves the kittens frequently.

Litters average 2 or 3 kittens, which are born spotted and yellow-brown. Kitten spots slowly fade but are not fully gone until about 2.5 years, when they reach maturity. The kittens will remain with their mother for up to 2 years, which spaces litters 2 or 3 years apart. Young mountain lions do not breed until they have established a home range. Females may locate near their mother, but males may travel very long distances to find a range, occasionally far outside the established mountain lion ranges. Young adult littermates may travel and hunt together.

Mountain lion life span is 8 to 13 years in the wild. On average only 1 kitten survives from a litter, falling prey to other adult mountain lions, bears, or wolves. Adult males can have aggressive conflicts with each other, and both sexes become involved in deadly disputes over prey with wolves or bears. Adults also lose their life to starvation, traffic accidents, ingestion of rodent poison, and hunting.

Legalities

The Florida panther is protected as Endangered. Most western states permit mountain lion hunting but regulate it as with game animals; Texas, however, allows mountain lions to be hunted at any time. Mountain lions are protected in California and in central and eastern states, as well as in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Ontario. Depredation permits may be issued in cases of human, pet, or livestock safety.

Beware the Hoax

Be aware that many false, inaccurate, or hoax stories and images of mountain lions circulate on the Internet. Forced perspective or altered images can make mountain lions appear to be incredibly large. Photos are often misidentified as to location as well.

Human Interaction

Mountain lions are important predators of deer and other ungulates and a keystone species in the ecosystem. To a lesser extent, they also prey on livestock and pets and may attack humans. Although conservation programs have shifted the emphasis to coexistence and nonlethal control methods, sport hunting is allowed in some states, and depredation permits are issued for problem animals. While targeted depredation removes a problem animal, sport hunting can be counterproductive, especially when mature adult mountain lions are hunted as trophy animals. When a resident nonproblem adult is removed, a younger, inexperienced mountain lion moves into the area. In some cases, removal can be shown to increase predation on stock.

Mountain Lion Encounters

Human encounters with mountain lions are very rare, because the big cats are far more likely to avoid being seen. At times they may simply be curious or startled. Less commonly, humans stumble into a situation in which a mountain lion is hunting or has made a kill. Encounters are more likely where both the human and the mountain lion population is high. Coming upon a mountain lion face-to-face usually occurs in recreation areas or where housing is adjacent to mountain lion habitat that provides both cover and prey.

Mountain lion attacks have been increasing since the 1970s, with an average of 4 to 6 physical altercations per year in the United States. Although records vary, approximately 30 human deaths have been attributed to mountain lions since 1890, far fewer than the 20 to 30 deaths caused by dog attacks each year in the United States. The majority of victims are children. The most recently reported physical attacks have been in California, Washington, Colorado, and Vancouver Island, British Columbia.

While attacks are extremely uncommon, people who live, work, or enjoy recreation in mountain lion country should be sensibly prepared to deal appropriately with an encounter. Pay attention to local news regarding mountain lion sightings, attacks on pets, or habituated mountain lions. Signs of a habituated mountain lion include the animal being active during the day, showing no fear of humans, or approaching humans. Report all abnormal mountain lion behavior to local authorities and state departments of natural resources or the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

Attacks on humans are more common from dusk through dawn when the mountain lion is hunting or during late spring or summer when mountain lions are more desperate for food and/or young mountain lions are first on their own. Although younger mountain lions threaten people more often, adult mountain lions are responsible for more actual deaths. Children and smaller adults who are alone are viewed as more vulnerable. Children seem to attract a mountain lion’s attention because of their size, quick movements, or high voices; therefore, they should be taught how to handle an encounter.

Recreation Guidelines in Mountain Lion Country

- Don’t enter mountain lion territory from dusk through dawn.

- Look for active signs of mountain lions such as tracks, covered scat, or claw marks.

- Do not approach carcasses, which may be covered with leaves or other debris and may be attracting vultures.

- Remain in groups, not alone. Mountain lions are three times more likely to attack a solitary person.

- Make noise while walking, running, cross-country skiing, or biking in mountain lion areas. Slow down and be extra alert around blind corners.

- Do not allow children to run ahead or lag behind. The best position is right in front of an adult. A backpack is a safer method for carrying small children. The presence of children appears to increase the chances of an attack.

- Keep dogs on a leash. Although the presence of a dog can attract the attention of a mountain lion, it also seems to discourage attacks. Dogs also give advance warning of a nearby predator.

- Carry an air horn, pepper spray, a whistle, bells, walking sticks, and a strong fixed-blade knife. Individuals who must work in or frequent mountain lion areas may choose to carry a firearm if allowed. Firing several shots at a mountain lion that is attacking is effective, but a single shot is not.

- Store all food in airtight containers, especially when camping.

- Sleep in a tent or building, not out in the open.

Dealing with Mountain Lions

If you are in an area with mountain lion–human interactions, consider taking serious measures to discourage these animals from your yard and home, working with your neighbors if possible. Notice potential travel routes along washes, waterways, dirt roads, and trails. Be alert to environmental changes such as drought, fires, lack of prey, or increased habituation of a mountain lion near your home.

Homes and Yards

- Never leave children or pets unattended from dusk to dawn in your yard or when they walk to school or a bus stop.

- Eliminate attractants. In dry areas and drought periods, water also attracts mountain lions.

- Avoid any food sources or garbage that attracts rabbits, rodents, deer, and other wild animals that may in turn attract mountain lions.

- Don’t feed or encourage feral cats, raccoons, squirrels, wild birds, and other potential prey.

- Don’t use plants in your landscape that attract deer. Deer-proof landscaping is good protection against mountain lions.

- Feed pets inside or remove leftover food promptly.

- Eliminate the potential shelter of deep cover, spaces under decks, abandoned buildings, and refuse. Prevent access to other potential sites, such as large storm drains.

- Trim or prune bushes and trees, leaving several feet of bare trunks, especially near areas where children or pets play. Remove trees or branches that provide access to your yard over the fence.

- Remove cover on both sides of your perimeter fences, around gates and entryways, around your house, and in dark corners of your property. This not only reduces cover for the mountain lion and its prey but also improves your sight line toward a predator approaching your yard. A 50-foot open clearance around your property is advised.

- Use bright outdoor lights, especially where you walk; motion-activated light and sound devices; and very loud music to repel mountain lions.

- Consider keeping alert dogs that will sound an alarm if a mountain lion is nearby.

- Keep in mind that one livestock guardian dog (LGD) will alert you to a mountain lion and will attempt to scare it away, but it will take more than one to successfully battle an aggressive mountain lion in defense of children or stock.

Livestock Husbandry

Mountain lion attacks on stock can increase when preferred prey animals are not available. Maintaining grazing in good condition supports healthy prey populations. Theoretically, more prey takes pressure off stock, but mountain lion populations may also increase. In areas of prime mountain lion habitat, livestock producers can have continual predation. Research has proved that predation complaints increase by 50 percent when adult mountain lions in the area are killed, allowing young, inexperienced mountain lions to replace them. While targeted removal of a problem animal may be necessary, aversive conditioning or hazing by experts can also be effective.

- Remove potential sources of ambush or travel. Remove nearby cover up to a quarter mile from the farmstead and clear brush near important birthing areas.

- Use more secure and open pastures for small or vulnerable stock.

- Keep one LGD to alert you, but keep at least a pair to repel or confront a mountain lion. Mountain lions will fight with coyotes and wolves, so dogs are at risk in an attack.

- Make use of temporary night penning on range, which allows for more effective protection by shepherds, range riders, lighting, and LGDs.

- Remove sick or injured stock and carcasses.

- Use intermittent or motion-controlled flashing lights and sounds, such as very loud music, to scare mountain lions away. Note, however, that they may become habituated.

- Use fully enclosed pens with a sturdy roof or barns as the only mountain-lion-proof housing.

Fencing

Fencing to prevent mountain lion entrance is necessarily formidable and expensive. Substantial woven wire, chain link, solid material, or electric wire fences must be at least 10 feet tall with a 65-degree overhang facing outward. These materials are usually practical only in small areas.

- Create overhangs and extensions of solid material, barbed wire, or electric wire.

- Place wooden fence posts inside fences to prevent climbing.

- Make sure poultry and rabbit coops and runs are securely built and well covered. Cover windows and other openings with securely attached 1⁄4- to 1⁄2-inch-square hardware cloth or welded wire. Covers must support the weight of an adult mountain lion.

Mountain Lion Attack: Defending Yourself

Absolutely Do Not Do This

- Do not continue to approach a mountain lion — this will not intimidate it.

- Do not block potential escape routes or corner the mountain lion.

- Do not approach a feeding mountain lion, a mountain lion with kittens, or kittens who are alone even if they appear abandoned.

- Do not turn your back, engage in quick movements, or run. The mountain lion’s instinct is to chase fleeing prey. Do begin to back away slowly.

- Do not crouch or bend down, which makes you appear more like a prey animal.

- Do not play dead. Even standing still makes you seem vulnerable.

Do this immediately when a mountain lion is sighted.

- Protect small children and prevent them from running or screaming. Pick them up if at all possible but without bending over. Put them on your shoulders to make you both look larger. Have smaller people stand behind larger people.

- Face the mountain lion and maintain intense eye contact.

- Make aggressive actions, which reduce the chance of an attack. Make continuous noise; shout loudly and firmly; use air horns, whistles, or bells. Shouting has been shown to be more effective than a gunshot. Pepper spray is effective aimed at the mountain lion’s face. You may need to spray more than once.

- Appear larger by slowly opening or waving clothing or objects, such as opening and closing an umbrella or raising your arms over your head. Climb safely onto a higher object like a rock or log, if available.

- Throw rocks, branches, or objects at the mountain lion, without crouching down to pick them up.

- Back away slowly. If possible move toward open ground or a busier area with more people, vehicles, or homes. Seek a safe refuge but do not attempt to hide under something or to climb a tree.

- Remain alert if the mountain lion disappears. It may circle back behind you or follow you. Stay in open country.

Signs of aggression or an imminent attack by a mountain lion include:

- Crouching

- Intense staring

- Ears sharply forward or laid back

- Teeth bared

- Hissing or growling

- Tail twitching

- Hind feet kneading the ground

- Following your retreat

If a mountain lion attacks:

- Do not stop fighting.

- Hit the mountain lion with an object, your hands, or a fixed-blade knife — aiming for the eyes or face.

- Try to remain on your feet and facing the mountain lion. If knocked down, attempt to stand and protect your head and neck.

- Adult intervention and protection is absolutely necessary if a child is attacked.

- Never leave a victim alone. Other people in your group should attack and harass the mountain lion.

Damage ID: Mountain Lion

In the rare cases when mountain lions take poultry, they will carry it off. Larger animals may be completely missing, either cached or consumed. Scavengers are attracted to the carcass and complicate accurate assessment of initial cause of death. Locating a carcass on large or rough grazing areas is difficult.

Prey on

Horses, cattle (usually calves less than 200 pounds and 1 year of age), sheep, goats, and other small stock. Poultry predation is rare.

Time of day

Nocturnal but most active dawn and dusk; daytime where habituated to humans or in remote locations

Method of Kill

- Back of skull or neck bitten, revealing puncture marks; kill with a bite from above, breaking the neck and spine or biting at the head; occasionally they will bite at the throat like a coyote. Bite marks from upper canines will be 11⁄2–21/4 inches apart, generally larger than a coyote; lower teeth are 3⁄8–1⁄2 inch smaller. Bites are clean, not ragged, and cause deep wounds in this area.

- Claw marks on neck, face, shoulders, sides, or belly on larger animals

- Drag marks present, usually in a straight line for at least 10 yards up to 350 yards; carcass covered under brush, dirt, debris, or snow; rumen or organs often covered separately; scratch marks up to 3 feet in length. The mountain lion will return to feed again for several nights, often resting nearby, moving carcass and re-covering it after each meal until remains are left uncovered and abandoned.

- Hair and viscera removed from carcass before heart, liver, and lungs eaten; stomach untouched; large leg bones and ribs may be crushed; sometimes front quarters and neck or hindquarters fed on first

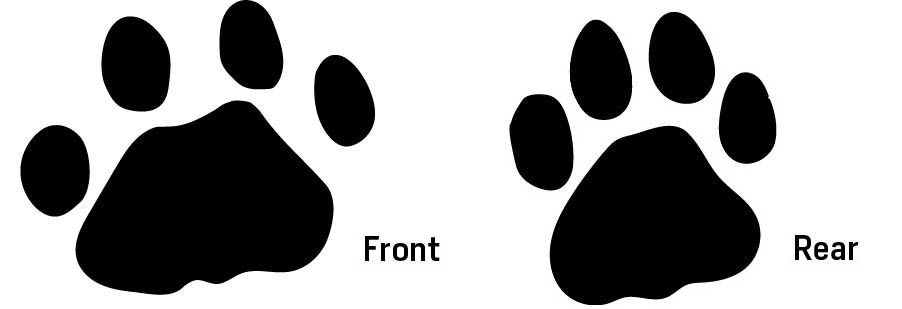

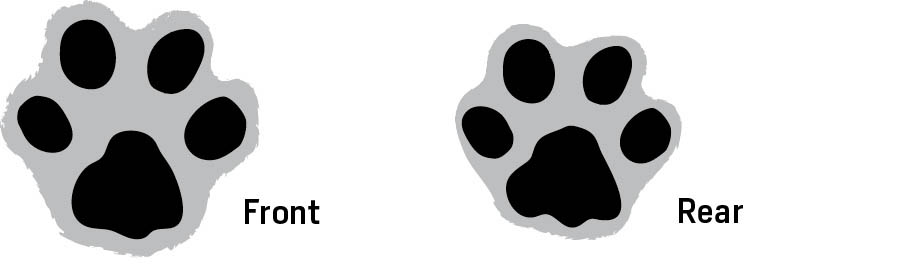

Track

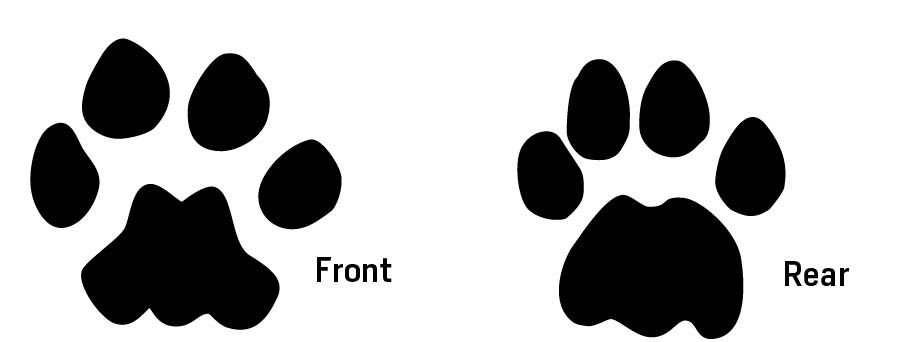

Front, 23⁄4–37⁄8 inches long, 27⁄8–47⁄8 inches wide; rear, 3–41⁄8 inches long, 21⁄2–47⁄8 inches wide. Distinctive 3-lobed heel pad 2–3 inches in width. Mountain lions move lightly and may not leave clear tracks on dry or hard ground. No claw marks. Teardrop-shaped toes. Can identify left or right prints because they slant like a human footprint.

Gait

Primarily walk, with stride length up to 32 inches. Will overstep or direct-register (step in the print or overlap it) the front track at a walk. The stride at a gallop can be 3–10 feet, with leaps up to 25 feet.

Other Sign

Claw marks on trees, 4–8 feet above ground. Long, deep, parallel scratches without much bark removed, unlike with a bear.

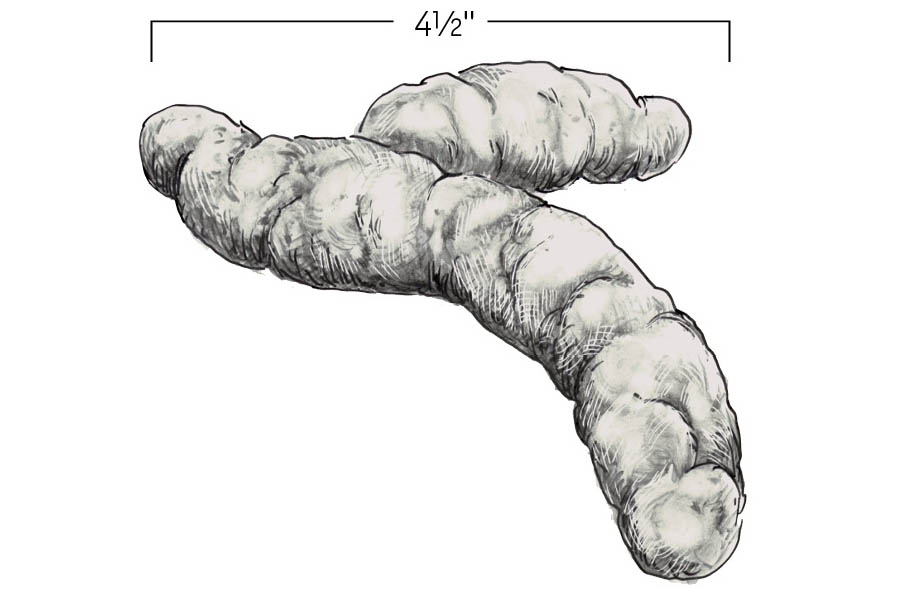

Scat

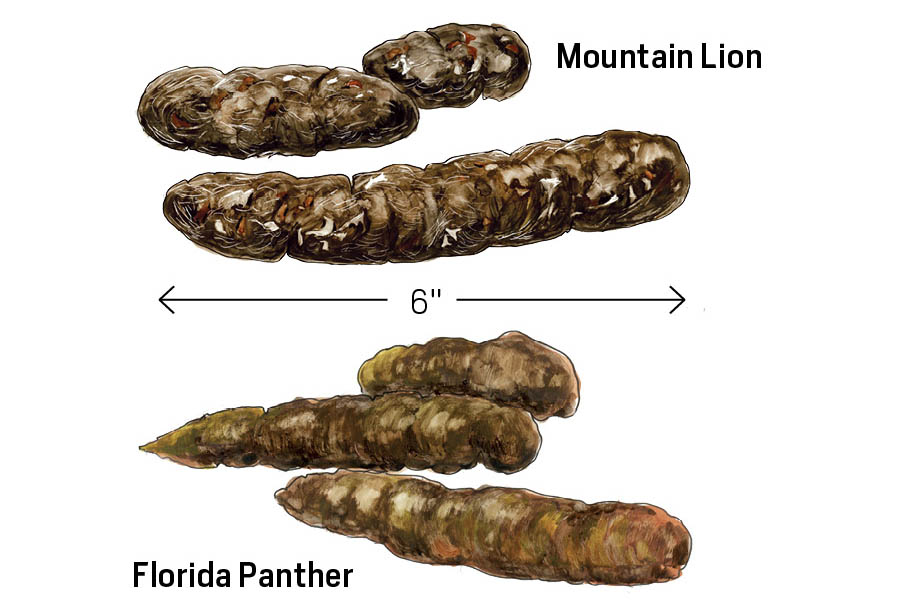

Blunt ends, 4–6 inches long and about 11⁄4 inches in diameter (size may indicate the relative size of the mountain lion). Usually covered, may contain cut pieces of bone and hair.

Jaguar (Panthera onca)

Often called el tigre in Mexico, a name bestowed by the Spanish, the jaguar is the largest cat in the Americas and the third-largest cat in the world. It is an important symbol of power in the Aztec and Mayan cultures, and jaguar images are found on the artifacts of North American native peoples as well.

In 1544, John Cabot recorded that jaguars were present in Ohio and Pennsylvania. In 1799, Thomas Jefferson noted that a jaguar weighed 200 pounds. Jaguars were occasionally spotted as far away as southern California, Colorado, and North Carolina. In the early 20th century, jaguars were still present in Arizona, California, New Mexico, and Texas.

Widely hunted for pelts, jaguars were rapidly exterminated in many areas of the Americas. A population of 15,000 jaguars may still exist in the wild, although numbers are still declining rapidly due to loss of habitat and hunting. International protection was achieved in 1973. The last female American jaguar was shot in 1963, followed 2 years later by the last males. In northwestern Mexico, the jaguar population numbers about 80 to 120 animals, and since the 1990s, individual jaguars have been spotted every few years in Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.

Description

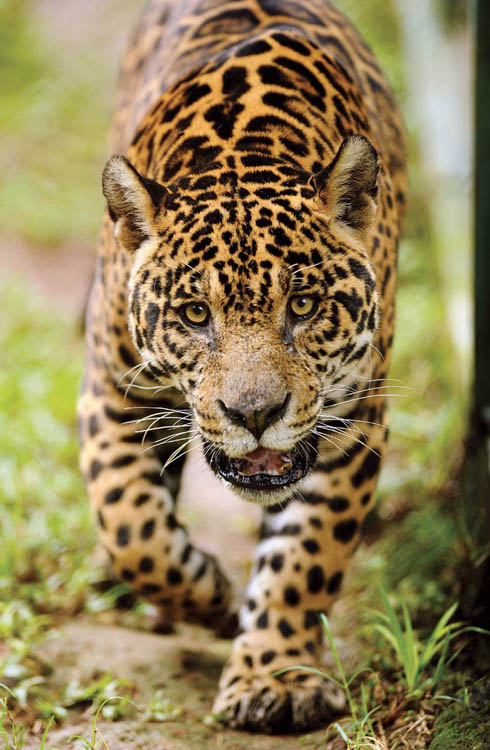

The jaguar shares a distant common Asian ancestor with lions, tigers, and leopards. Built for power more than speed, it has a larger head and broader jaw than the mountain lion, along with a more powerfully muscled body; shorter, sturdy legs; and a shorter tail.

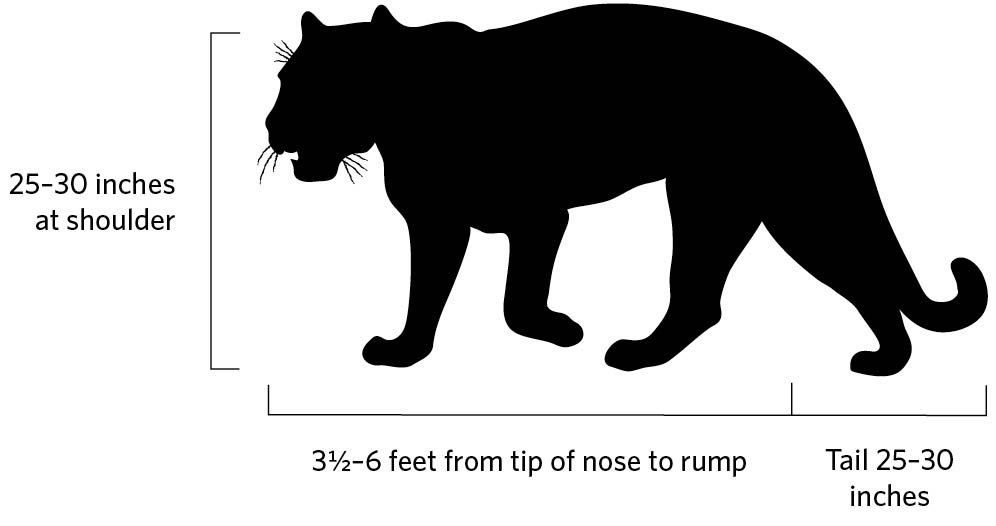

Size. Jaguars weigh 100 to 260 pounds and range from 3.5 to 6 feet long, excluding the tail, although individual animals can be longer. Females are slightly smaller than males, and size variations occur in different regions. The largest jaguars are found in the Brazil Pantanal, with smaller jaguars seen in more open habitat.

Coat and coloration. With a reddish buff to light gold base color, the black rosettes or rose-like spots provide camouflage on the upper body, with solid black spots on the head and neck, and off-white underparts. Black jaguars, which form about 6 percent of the population, actually have a black base color with black spots.

Habitat and Behavior

Although the jaguar more closely resembles a leopard, its behavior and habitat are closer to the tiger’s. Dense tropical forests are preferable, but jaguars will also use swamps, scrubland, thickets, and coastal forests that are near rivers, streams, or still waters. Jaguars are not common in arid or higher mountainous areas. The protected jaguar area in the United States is mainly oak, pinyon pine, juniper woodlands, wooded riverways, and mesquite thickets.

Jaguars maintain a home range that varies from 4 to 65 square miles, with females occupying smaller territories within the much larger home range of a male. The jaguar roars deeply like a lion to identify its territory, and it also communicates through grunting.

Hunting and foraging. Nocturnal hunters, jaguars are most active during dawn and dusk, resting at midday and seeking relief from heat in caves, under large rocks, in or near water, or in deep vegetation. Pouncing from hidden cover or high in a tree, they can take medium to large mammals and reptiles, in addition to birds, fish, and opportunistically smaller prey. If they take prey at the water’s edge, jaguars will follow it into the water, as they are excellent swimmers. Jaguars will also fish from shore, grabbing fish with their claws. They can easily drag prey 3 to 4 times their weight for distances up to a half mile to reach a more secluded area. After hiding or burying the carcass, they will return to it to feed.

Life Cycle

Female jaguars mature at 1 to 2 years of age, and males at 3 or 4. Jaguars are solitary animals except during estrus, which may occur year-round. Two cubs are most common, usually born in wet seasons when prey is more plentiful. They remain with their mother for about 2 years as they learn to hunt. The jaguar’s life span in the wild is 11 to 12 years, and longer in captivity. Humans are the primary threat to jaguars through illegal poaching, trophy hunting, or killing by ranchers or farmers.

Human Interaction

Essentially secretive animals, jaguars may take cattle, horses, or other livestock. They are not known to stalk humans, although attacks have occurred with habitat encroachment and loss of prey due to human hunting.

Now occupying less than half of their original range, jaguars are found primarily in 18 countries of Central and South America, from Mexico south to northern Argentina and Paraguay, northeastern Brazil, and the Amazon basin. The Brazilian Pantanal is home to the greatest density of jaguars. The Jaguar Corridor Initiative conservation program seeks to link the breeding populations in isolated areas from Argentina through Mexico and supports mitigating efforts between humans and jaguars.

Believing that jaguars regularly cross the borderland, the US Fish and Wildlife Service established an official habitat nearly 1,200 square miles along the Mexican border in southern Arizona and New Mexico in 2014. Any large or extensive fence or barrier between the countries would prevent a critical exchange of genetics.

Legalities

Jaguars are protected under the Endangered Species Act and listed as Threatened with Extinction by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. All international trade in jaguars or their parts is prohibited through the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

Dealing with Jaguars

Jaguars are exceedingly rare in the United States. It is highly unlikely for a person to encounter the elusive hunter outside of the very small areas where they have been observed, primarily by cameras at night. Most experts do not believe a breeding population is present in the United States at this time.

Damage ID: Jaguar

Prey on

Small and large livestock

Time of day

Nocturnal; most active dawn and dusk

Method of Kill

- Prey pounced on from cover or trees and killed with a bite to the throat or skull

- Carcass dragged to a secluded location and covered between visits

- Neck and chest eaten first, heart and lungs consumed, followed by the shoulder area

- Territory marked with circular scrapes of dirt around scat, brush piles soaked with urine, and clawed trees

Track

Front 27⁄8–47⁄8 inches long, 3–47⁄8 inches wide; rear 23⁄4–4 inches long, 21⁄2–41⁄2 inches wide; no claw marks; larger than mountain lion, with broader, rounded tips on the toe imprints

Gait

Stride at walk 16–32 inches or more, direct-register or overstep

Scat

Blunt or tapered ends, 5 inches long and 11⁄2 inches in diameter, often wrapped in fur

Bobcat (Lynx rufus)

Although most people have not seen a bobcat, at least 1 million of these North American wildcats live in the United States. Indications show that the population is increasing in most areas, and their range is expanding. Bobcats are highly adaptable, living in deep forests, wooded or brushy farmlands, mountains, scrublands, deserts, and swamps. They are increasingly seen in suburban and urban environments as well, being opportunistic and flexible in diet, unlike their cousins the Canada lynx. The bobcat’s modern success in adaptation is similar to that of the coyote. When it is sighted, however, the bobcat is often confused with a feral cat, a mountain lion, or a lynx.

Evolved from the Eurasian lynx, which migrated to the Western Hemisphere about 1.8 million years ago, the species was present as the modern bobcat by 20,000 years ago. Originally, the animal was called the wild cat by the European colonists; the common name bobcat, for its bobtail, did not appear until the 19th century. The earliest settlers hunted and trapped bobcats for fur and sport. Even today some 30,000 pelts are exported from the United States each year, down from a high of 90,000 pelts in the late 1970s.

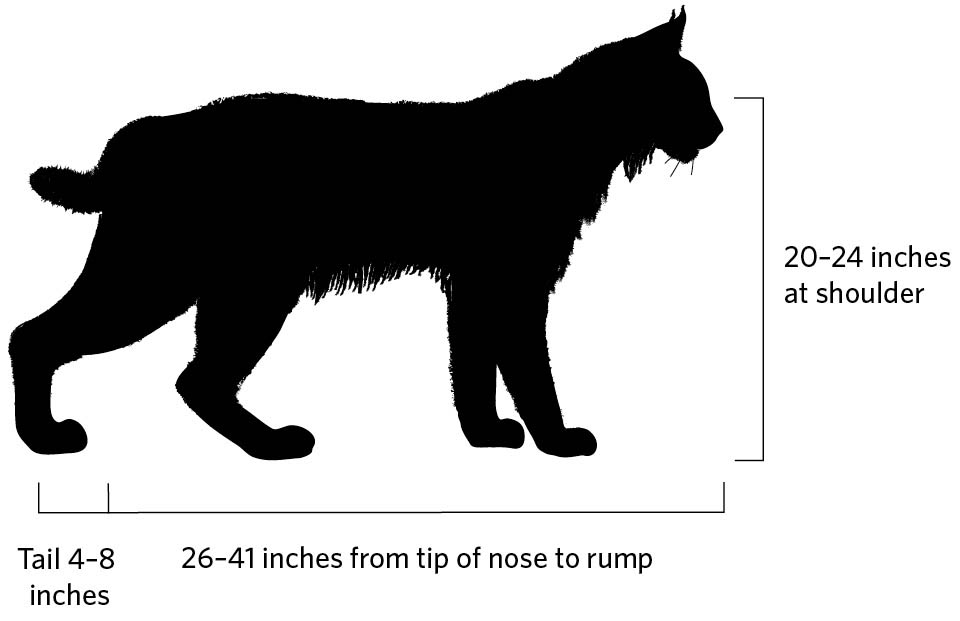

Description

A bobcat is usually taller and twice the size of a domestic cat, with longer hind legs, a distinctive ruff, and a bobtail. It is usually smaller than a mountain lion, is differently colored and patterned, and lacks the long tail. Compared to the rarer lynx, the bobcat is usually shorter and stockier, with much smaller feet. It is more heavily boned and muscular than a large domestic cat, even when similar in size.

The bobcat has excellent sight, hearing, and smell. It uses its retractable claws to climb trees to escape threats and can swim if necessary. The hind legs are longer than the front legs, but not so long as on the lynx.

Size. Bobcat size varies by location as well as by sex, with males significantly larger than females — from 25 to 80 percent larger. Bobcats can range from 26 to 41 inches long, 20 to 24 inches tall, and 11 to 40 pounds; however, on average a bobcat will weigh around 20 pounds. Their distinctive bobtail is 4 to 8 inches long.

Coat and coloration. Varying according to habitat, bobcat coloration provides excellent camouflage. A bobcat may be light gray, yellowish, or reddish brown, with dark brown to black stripes and spots, a dark line running down the back, and bars or stripes on the front legs and the tail. The back of the ears is black, as is the top of the tail tip. The chin, throat, and underparts are lighter. The ears have slight tufting. The facial ruff makes the face look round, although it is noticeably smaller than the distinctive ruff of the lynx.

As many as 13 separate subspecies exist, although taxonomic disagreements exist over the exact divisions. Bobcats certainly have varying size, coat color, and spotting patterns. They tend to be lighter in deserts and darker in northern forests. Bobcats are more yellow or red in the southern states, with a few rare black bobcats in Florida. Longer hair is found in cold climates. Bobcats are usually larger in the West and in the North, and smaller in the South.

Lynx–bobcat hybrids are sometimes located where their habitats overlap, such as Minnesota, Maine, and New Brunswick in Canada. These offspring are fertile and possess larger ear tufts than the bobcat, but smaller feet and bobcat-like coats.

Habitat and Behavior

Bobcats are found in many diverse areas, including forests, grasslands, scrublands or deserts, canyons, wooded streams or river land, mountains, swamps, subtropical forests, and farmlands with nearby dense cover. They are increasingly seen in suburban and urban areas where they can obtain water, food, and shelter. They are generally absent from large urban areas on the coasts and from areas in the Midwest where agricultural fields are large and lack sufficient shelter or cover. They are not adapted to deep snow like the broad-footed lynx, which limits their range. With climate change and land clearing, the bobcat is moving into some areas formerly held by the lynx.

Bobcats use rock ledges, caves, brush piles, hollow logs, and abandoned animal dens for shelter, often maintaining several spots in their range. They are territorial, marking their individual ranges with scent and claw marks. Males can be somewhat tolerant of nearby males. While several female ranges may overlap a male’s range, females do not associate with one another. Bobcats will use animal and human trails as well as remote roads for travel within their home range. Range sizes vary with climate, habitat, availability of food, and predator threats.

Hunting and foraging. Bobcats are solitary but less reclusive and more aggressive than lynx. They begin to hunt well before dusk and can continue into the morning after sunrise, but they can also be out during the day, especially during fall and winter, in search of food. They hunt primarily on the ground, both ambushing and stalking their prey. Although fast sprinters, they are not distance runners, pouncing on their prey and killing with a bite to the neck.

They prefer rabbits and snowshoe hares but also hunt squirrels, rodents, small mammals, and birds including large turkeys, geese, swans, or cranes, and also nestlings or eggs. They occasionally hunt deer, usually waiting until the deer are bedded down. Bobcats will infrequently kill small livestock, rabbits, piglets, poultry or other birds, and domestic cats or small dogs. They will also scavenge carcasses and opportunistically eat small predators, fish, reptiles, amphibians, and insects. They cover larger kills or scavenged carcasses with leaves, debris, or snow and return to feed again several times. They will aggressively defend a carcass.

Life Cycle

Breeding season can vary in different locations but usually occurs in late winter or early spring. Males and females can have multiple partners, and when breeding they will yowl and scream like domestic cats. About 60 days later, 1 to 6 faintly spotted and streaked kittens are born. Kittens usually stay with their mother for at least 8 months. At times, litters can arrive as late as fall. Females can breed the following year, with males generally a year later.

In the wild, bobcats can live 12 years or more. Other predators, including other bobcats and raptors, prey on young bobcats. Mountain lions, wolves, coyotes, or other large predators will kill adults. Road accidents, starvation, disease, and poisoned baits also take their toll, but half of adult bobcat deaths can be attributed to hunting or trapping.

Human Interaction

Bobcats are an important predator in the ecosystem and are especially useful in the control of rabbits, rodents, and pest species such as cotton rats. When bobcats prey on livestock, sheep, goats, and poultry are the most common victims, but they will also take calves, domestic rabbits, piglets, other birds, and eggs. Bobcats will also prey on domestic cats, small dogs, and exotic or pet birds.

Legalities

Bobcats are protected as Endangered in Indiana, Iowa, and New Jersey. Hunting or trapping is regulated in most states and Canada, although some states have continuously closed hunting seasons. Some states allow landowners to kill a bobcat without a permit. Check with state or provincial authorities before dealing with a problem bobcat. Report potentially dangerous bobcats to local authorities for removal. Keeping a bobcat as a pet is illegal in many states or requires a permit.

Bobcat Encounters

Rarely seen, bobcats behave cautiously around humans. They will growl, hiss, or spit if threatened or protecting a kill. Bobcat attacks on humans usually involve rabid or unusually aggressive individuals.

Open all gates and remove dogs if a bobcat is in a yard. If the bobcat is up a tree, it may have been chased there by a dog or may be just resting. Stay indoors, remove pets from the area, and contact authorities.

Do not pick up or approach a bobcat kitten, despite its adorable appearance. Even if you do not see her, the mother will be extremely protective if she perceives a threat to her offspring. If a bobcat has kittens in a den on your property, exercise caution and keep people and pets away. The mother may be encouraged to move her kittens if you play continual loud noise or flashing lights, although she will be reluctant to move them if they are very young. Seek assistance if necessary.

If You Meet a Bobcat

- Do not approach the animal.

- Do not run, but do back away slowly from the bobcat or its kill.

- Pick up and protect small children.

- Make loud noises, use air horns, or spray water, if available.

- In the rare case of an attack, the bobcat will target the head, neck, or shoulders. Use pepper or bear spray, fight off and hit the cat, try to protect your head and neck, and make loud noises.

Dealing with Bobcats

Homes and Yards

In suburban or urban areas, you may need to work with your neighbors to discourage bobcats. Be aware that roads or trails through your property may be used by bobcats to access prey.

- Eliminate all attractants, including water in arid areas.

- Do not feed wild birds or animals in your yard.

- Do not feed bobcats.

- Do not leave pet food or water outside.

- Clear brush and other hiding places in your yard and around buildings, cover access under decks or porches, and secure buildings and animal housing.

- Keep backyard poultry or other pet birds securely penned; the pen must have a secure top, not a tarp or flimsy netting. Cats and dogs may need similar protection if left alone in the yard.

- Use LGDs, which provide excellent protection in larger yards.

Livestock Husbandry

- Keep vulnerable animals in more secure and protected pastures or paddocks, for example, during livestock birthing seasons.

- Remove sick or injured animals and carcasses.

- Use electronic motion-sensor guards with sounds or lights.

- Play loud music or shine continuous bright lights to temporarily discourage bobcats.

- Maintain a human presence to discourage bobcats.

- Use LGDs, which provide excellent protection.

Fencing

Bobcats can easily jump 6 feet, and may jump up to 12 feet.

- Make sure that fences are tight and secure.

- Place electric scare wires outside the fence at 12 and 18 inches above the ground with another near the top of the fence.

- Add an overhang, extending outward from the top of the fence.

- Place metal or plastic guards at least 5 feet high to discourage bobcats from climbing wooden posts and other structures, trees, and overhanging branches to gain access to pens or yards.

- Construct pens from woven wire or multiple stands of electric fencing, including a sturdy roof or cover.

Damage ID: Bobcat

Prey on

Small or young livestock, poultry, pets

Time of day

Before dusk through early morning; daylight hours during fall and winter

Method of Kill

A field autopsy is important to determine whether the animal was killed or just scavenged by a bobcat. It can be difficult to distinguish between cougar, coyote, or fox kills when a carcass is discovered.

- Poultry dead, head and neck bitten; shoulders bitten on large birds; head eaten

- Small animals killed by a single bite to the head, neck, or throat, killing the animal through suffocation or shock; jugular vein often punctured; bite mark with a 3⁄4- to 1-inch space between the canine teeth, smaller than a mountain lion’s bite; claw marks on the shoulders, back, or sides that leave hemorrhages

- Adult animals usually attacked when bedded down, seized by the neck, then bitten on the back of the skull, throat, or front of chest; claw marks visible on the back, shoulders, or sides

- Animals dragged or carried away; small animals and birds eaten completely

- Larger animals eaten under the ribs, beginning with viscera but leaving the rumen, or from the neck, shoulders, or hindquarters. Both bobcats and mountain lions leave cleanly cut edges on bone and tissue, compared to the ragged edge left by canines.

- May return to larger kills several times, moving the carcass and covering it with soil, debris, or snow, leaving marks showing a 15-inch reach (compared to mountain lions’ 24-inch reach)

- Once bobcats find prey at a location, they will return to seek more.

Track

Front 15⁄8–21⁄2 inches long, 13⁄8–25⁄8 inches wide; rear 11⁄2–21⁄4 inches long, 11⁄4–25⁄8 inches wide. No visible claws; 4 toes and pad visible.

Gait

Walking stride about 12–18 inches, overstep or direct-register. Running stride up to 4 feet.

Scat and Sign

Blunt, dry, 3 inches long, and 3⁄4 inch wide. Kittens cover their feces, but adults leave feces uncovered.

other Sign

Claw markings 10–12 inches long on trees

Canada Lynx (Lynx canadensis)

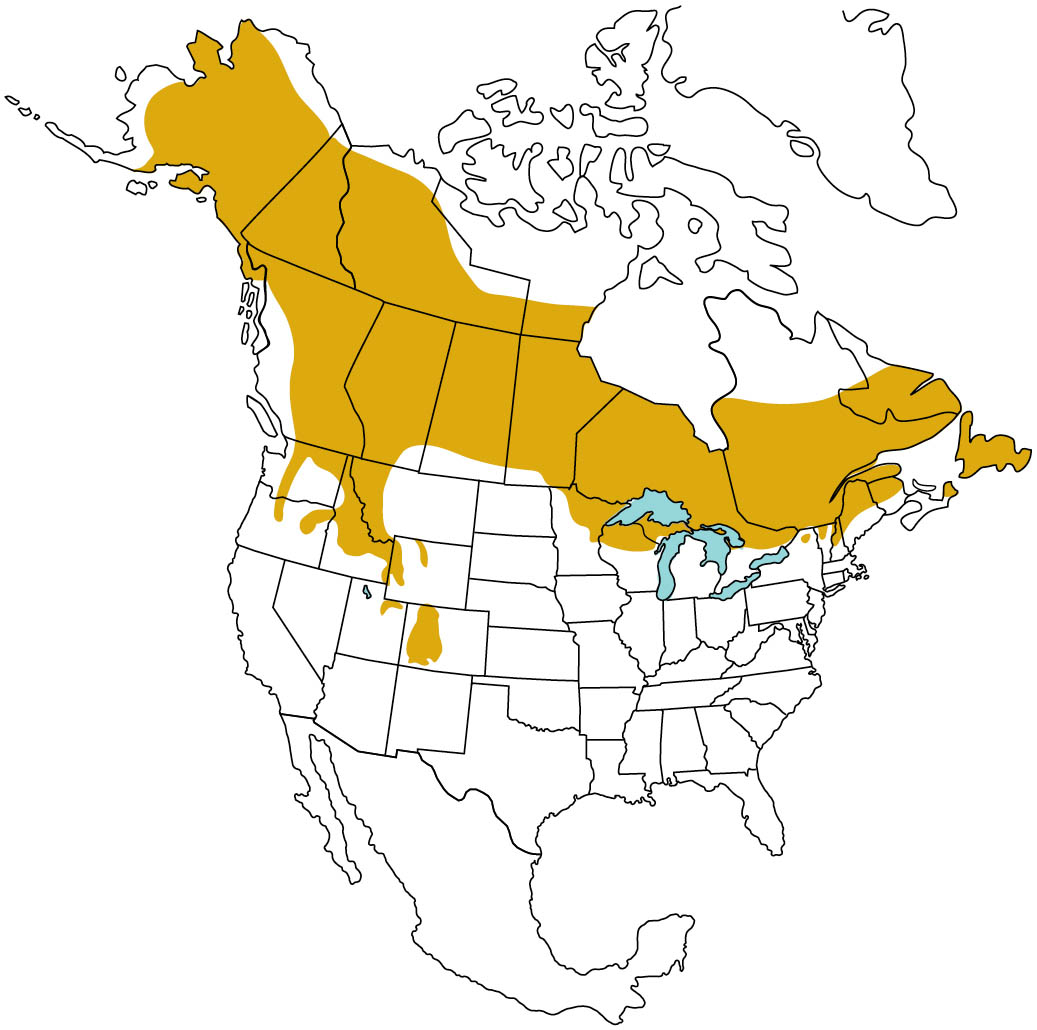

Easily confused with the bobcat, the other member of the lynx family in North America is the Canada lynx. Genetic evidence suggests the Canada lynx is actually descended from a much more recent migration of the Eurasian lynx into North America. It is more commonly just called the lynx, and it has evolved to be a highly specialist predator of the snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus). The hare forms the majority to the entirety of the lynx’s diet when available. In Alaska and Canada, the snowshoe hare has an approximately 10-year-long population cycle building up into a boom followed by a bust. The crash in snowshoe numbers dramatically affects the lynx population as well.

The lynx now occupies the portion of the snowshoe’s range where it has little or no competition from other predators — the dense forests of interior Alaska and Canada. The historic range of the lynx extended south into 24 US states across the North and into the Rocky Mountains. In the 19th century, habitat loss and trapping reduced the population in many areas, although it remained stable in more remote terrain. Again in the 1970s and ’80s, high prices for lynx pelts raised growing concern in terms of species vulnerability. In 2000, the Endangered Species Act listed the lynx as Threatened in the lower 48 states. In 2014, critical habitats were designated in Maine, Minnesota, Montana, Idaho, Washington, and the Greater Yellowstone area in Wyoming. Washington and Montana have the largest populations outside of Alaska and Canada.

Description

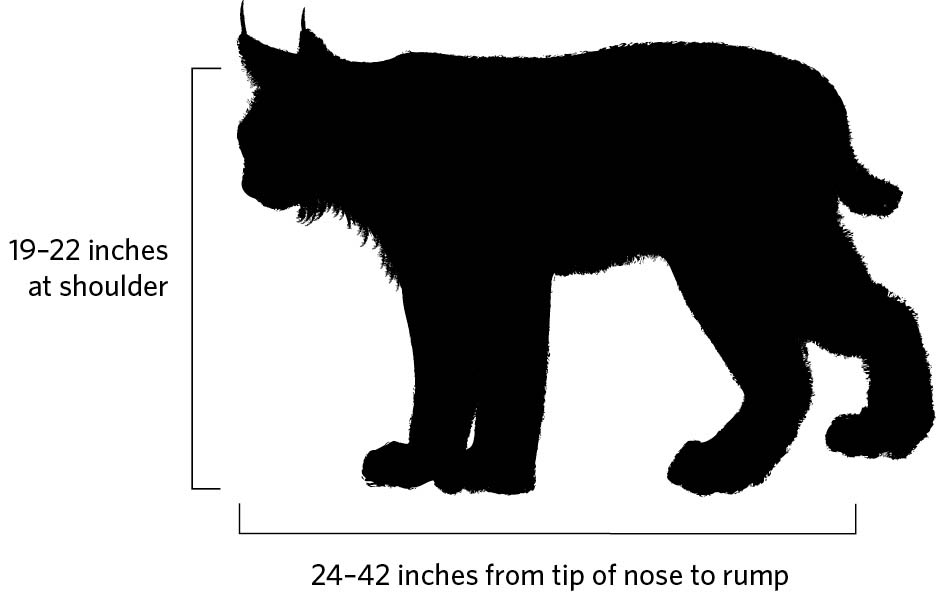

Size. Smaller than the Eurasian lynx, the lynx is typically larger than most bobcats. Ranging from 10 to 38 pounds, Canada lynx average 22 pounds, with males larger than females. Standing 19 to 22 inches tall, lynx can be from 24 to 42 inches long. The lynx has a small head and very long legs. The hind legs are longer than the front, much like a jackrabbit’s. The large, broad paws, equipped with retractable claws, are well suited to deep snowpack. The lynx is a good climber and swimmer, able to cross large rivers. It has excellent hearing and vision. Of the 3 subspecies, the Newfoundland lynx is large enough to kill caribou calves.

Coat and coloration. The lynx has a long, thick coat in winter, colored silvery or grayish brown and turning more reddish or yellowish brown in summer. The dark brown or black spots or small stripes are less defined than on the bobcat. White tips on the hairs give the lynx a frosted appearance. The lynx also has a very distinctive double-pointed long facial ruff and long black tufts on large, triangular ears. The ruff is as sensitive as the whiskers. The tail is shorter and blunter than that of the bobcat, colored brown to whitish buff with black hair encircling the tip. The blue lynx, a rare genetic mutation, is a very pale color.

A lynx should appear twice the size of a domestic cat, closer in size to a medium-sized dog. Lynx appear grayer than bobcats, with their very distinctive facial ruff, ear tufts, and black-tipped short tail.

Habitat and Behavior

The lynx lives primarily in cool, mature coniferous forests with dense undergrowth, deep snow, and fallen timber. It may hunt in younger forests with thick vegetation and in rocky areas or tundra but is less common in mixed forests or wooded farmland. Lynx shelter under rock ledges or fallen timber in dense areas of the forest. Females choose a birthing site in thick brush, thickets, woody snags, or hollow logs and do not dig dens. Loss of timber, both mature trees and fallen logs, negatively affects the lynx, as do roads for logging or recreation, which allow other predators increased access to the snowshoe hare.

The range of a male lynx is usually less than 20 square miles but will increase when prey is scarce and the cats roam even farther in search of food. Female territories may overlap each other and that of the male. Young females usually occupy ranges near their mothers, and adult mothers and daughters may continue to travel or hunt together, although lynx are usually solitary hunters. Generally nocturnal, lynx are most active during dusk and dawn, and they may hunt or travel during the day when necessary. They can hunt in deep snow and at higher altitudes, both walking on the ground and on fallen timber. Lynx either ambush their prey or actively search and flush them from cover. Lynx are very fast at a sprint but do not have stamina and will only chase prey a few dozen yards.

In the absence of their preferred prey, lynx will hunt small- to medium-sized animals such as squirrels, rodents, and ground-nesting birds. In fall and winter they will occasionally take hoofed mammals. They also scavenge carrion. In the southern areas of their range, their diet is likely to be more diverse.

Life Cycle

Lynx breed in winter or early spring. Females mate with only one male, although the male may breed several females. About 64 days later, 1 to 6 kittens are born and become fully independent 10 months later. Young females breed when they are 1 or 2 years old, with males waiting another year. In the wild, lynx can live 14 to 16 years. Secretive and reclusive, the lynx is less confrontational with larger predators compared to the bobcat. While young lynx fall victim to larger predators, both adults and young are lost to starvation, road accidents, or trapping.

Lynx–bobcat hybrids are sometimes identified near the limits of the lynx range in Minnesota, Maine, and New Brunswick in Canada. These offspring are fertile and possess large ear tufts but smaller feet than the lynx and have bobcat-like coats.

Human Interaction

The lynx is an important predator of the snowshoe hare. Lynx rarely kill sheep, goats, domestic rabbits, cats, poultry, or game birds. The lynx is trapped for fur in Alaska and most of Canada.

Legalities

Outside of Alaska, lynx are protected as a Threatened species in the United States and as Endangered in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Regulated trapping seasons are allowed elsewhere in Canada and Alaska.

Lynx Encounters

In the United States, an encounter with a lynx would be extremely rare outside of their known range. The secretive feline may be spotted near the forest edge but is rarely seen. The only two reported attacks on humans involved people carrying dead snowshoe hares or wearing buckskin; both were believed to be a case of mistaken identity by the lynx.

Dealing with Lynx

Homes and Yards

- Clear brush and fallen trees, since the lynx uses them for hunting.

- Play loud music, shine irregular or bright lights, and produce other sounds as good frightening techniques from dusk through dawn, since lynx avoid all human activities.

- Use LGDs; their barking is a good deterrent. Lynx are not usually aggressive toward dogs.

Livestock Husbandry

Predation on sheep, goats, calves, or poultry is more likely in the fall and winter or when the cyclical snowshoe hare population is low. Keep stock in safer areas during these times. Clear brush and fallen trees away from animal enclosures and paddocks.

Fencing

Woven wire should protect the sides and tops of pens or coops, since lynx can climb wooden fence posts and can jump 6 feet high.

Damage ID: Canada Lynx

Prey on

Sheep or goats, rabbits, poultry, domestic cats

Time of day

Nocturnal, most active dawn and dusk

Method of Kill

Lynx will opportunistically feed on carcasses of dead stock. A field autopsy is essential before assigning blame to a lynx found feeding on a carcass.

- Poultry killed less often by lynx than by other animals

- Birds killed by a bite on the head or neck; head eaten; eggs eaten

- Small stock, rabbits, and domestic cats killed by a bite through the top of the head or neck by the lynx’s 4 long canine teeth

- Larger animals jumped on, their shoulders or back attacked, with claw marks left on their sides, their throat bitten; killed by suffocation

- Hindquarters usually eaten first, along with shoulder, neck areas, and flank

- Larger prey or a scavenged carcass dragged and cached under brush or rocks, covered with leaves, scratched out 12–14 inches.

- May kill several smaller animals and cache them

Tracks

Front 23⁄8–41⁄4 inches long, 23⁄8–55⁄8 inches wide; rear 21⁄2–41⁄8 inches long, 21⁄8–5 inches wide; often indistinct due to heavy fur, small size of pads, or in deep or fluffy snow. In fluffy snow track may leave a uniquely cross-shaped mark. No claw marks.

Gait

Walking stride 11–19 inches, overstep or direct-register

Scat

Blunt, dry, 41⁄2 inches long, and 3⁄4 inch in diameter; not covered

Other Cats

Jaguarundi

(Puma yaouaroundi)

Despite the significant difference in size, the jaguarundi is closely related to the mountain lion. Its range extends from Brazil and Argentina, north through Central America and Mexico, and into the United States. In the United States, the extremely rare jaguarundi has a protected area at the Laguna Atascosa National Wildlife Refuge, although its presence has not been confirmed in Texas since 1986, when a dead jaguarundi was found on a roadside. Other sightings have occurred in southern Arizona; the area of Big Bend, Texas; Florida; and coastal Alabama. The small population in Florida may be an introduction. It is protected as an Endangered species in the United States, although unthreatened elsewhere in its range.

Only a bit larger than a house cat, the jaguarundi is somewhat weasel-like in its facial appearance, giving rise to its nickname the weasel cat. It has a long body, shorter legs, and a long, somewhat flattened tail. It weighs from 7 to 20 pounds and ranges from 21 to 30 inches long, with a 13- to 23-inch-long tail. Its head is small and flat, with a weasel-like nose; small, rounded ears; and somewhat narrow eyes. Jaguarundis come in 2 uniform colors — shades of gray and red. Light tawny-red cats can resemble a small mountain lion.

The solitary and shy jaguarundi is active in the day, hunting on the ground for small mammals, reptiles, and birds. Adaptable to a variety of habitats from dry to wet, jaguarundis seem to prefer forest edges and brushy lowlands. They are capable of reproduction year-round. The tracks and scat are very similar to those of the domestic cat.

For information on Domestic Cats

Ocelot

(Leopardus pardalis)

The beautiful ocelot once roamed throughout much of Texas, east to Arkansas and Louisiana, and west into Arizona, but it is now primarily found in the United States in southern Texas, where it is protected at the Laguna Atascosa, Lower Rio Grande Valley, and Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuges. Unfortunately, with fewer than 100 animals surviving in Laguna Atascosa, vehicles have struck several ocelots in recent years. In 2016, wildlife underpasses were constructed under roads around the refuge and efforts began to establish safe corridors for travel on nearby private land. A single ocelot was recently observed in Arizona. The ocelot is protected as an Endangered species in the United States, with a population estimated at 80 to 120. Ocelots in Texas may belong to 2 separate subspecies. Elsewhere, the ocelot’s range extends down the coastal areas of Central America to South America, where they are most numerous in the Amazon basin.

Ocelots are considered medium-sized felines, more slender than a bobcat, weighing 20 to 35 pounds, and ranging from 37 to 50 inches long. The legs are sturdy, the tail is short, and the ears are rounded. The stunning coats are uniquely patterned in each individual. The base color is tawny yellow to red to gray, with lighter underparts. The pattern is composed of brown rosettes with black borders, black spots, and stripes on the head, body, legs, and tail.

The ocelot is considered one of the most abundant and successful smaller cats. Ocelots prefer dense forests or cover, although they are found in varying habitats. Usually nocturnal, the solitary ocelot tends to sleep in trees where it can also capture monkeys, but it most often hunts on the ground for small mammals, rodents, reptiles, birds, and fish. Ocelots are capable of year-round reproduction. Despite an international trade ban on spotted cat pelts, ocelots remain vulnerable to habitat loss, illegal hunting, and roadside accidents. The tracks resemble those of the bobcat, about 2 inches across.