Chapter 5

Bears

Ursidae

Bears are “dog-like” carnivores that usually have nonretractable claws and long snouts. Eight species of bears are found in North and South America, Europe, and Asia. Large, powerful, and imposing, bears have been both hunted and revered by humans. Three species of bears are found in the United States and Canada — black, brown or grizzly, and polar bears. Migrating from Eurasia, both brown and black bears evolved separately from a distant ancestor some 5 million years ago.

Overview. North American bears have dense, long hair; large heads and bodies; long snouts; short tails; strong, stocky legs; and paws that walk plantigrade, or flat on the ground. Males can be up to twice as large as females, but both are the strongest large animal in North America, capable of lifting, moving, or dragging objects much heavier than themselves. They also deliver powerful blows with their front legs.

Many bears are excellent climbers, at least while young, and they all swim well. Although they walk slowly, bears have a fast and silent run. Bears can stand on their hind legs to walk a few steps, to reach higher for food, or to fight. Their most important sense is smell, which is 7 times better than that of a scenting breed of dog. Bears also have good hearing but poorer vision. Since they are nearsighted, bears probably do not see objects in detail at a distance. They often stand up to look at things in the distance, trying to catch a scent to aid in identification. Bears are widely recognized as intelligent, clever, and adaptable.

Varying in their diet according to habitat, bears are opportunistic feeders and roam constantly through their range in search of a wide variety of seasonal foods. About 85 percent of a black or a brown bear’s diet is plant foods, including grasses, sedges, shoots, buds, mosses, fungi, flowering plants, fruits, and nuts. They dig for roots, tubers, insects, grubs, worms, larva, and burrowing animals. Bears also strip trees of bark or tear apart logs for sap, insects, bees, and honey. They fish for salmon, trout, or bass and forage for eggs, nestlings, or birds. Bears scavenge carrion, and winterkills, or steal carcasses they can smell from 2 miles away. When they do hunt, their prey is generally small animals such as rodents or ground squirrels; newborns, fawns, or elk calves; new mothers; the infirm; or floundering animals. More rarely, black or brown bears prey on adult animals or livestock.

Bears are usually active during the day, but proximity to humans will lead them to forage more during the night or around dusk. This pattern also varies by season, especially in late summer and early fall, when bears need to forage up to 20 hours a day to increase their body weight in preparation for hibernation. Driven by hunger, both before and after hibernation, bears are less predictable toward humans they encounter during these times. Bears rest in dense vegetation, in a tree, or by a rock. On the ground they leave a slight roundish depression, often with some vegetation or branches on the ground in cold weather.

Generally solitary except during breeding season or while raising cubs, some young adults will band together for hunting or playing. Adult bears will attack smaller bears and each other at times. Bears do gather near exceptional food sources such as landfills and spawning salmon. The largest and most dominant bear will defend the best areas, and a hierarchy will develop.

Life Cycle. During breeding season, both sexes will mate with more than one partner, and cubs in the same litter may have different fathers. Males will attempt to defend a female from other males but will then leave her to bear her cubs alone. In female bears the embryo remains dormant, a process known as delayed implantation, until fall when she hibernates. About 3 months later, while she sleeps, 2 to 3 cubs are born weighing only about 1 pound. This young-to-adult size ratio is the smallest of any placental mammal. Helpless and nearly hairless, the cubs wake, nurse, and grow until they emerge from the den with their mother later in the spring when the snow melts. The cubs remain with her until the next spring or even after their mother’s breeding the next summer until she forces them out of her territory. Generally female bears have litters 3 to 6 years apart, a very low reproductive rate.

The form of hibernation in bears is more accurately called winter dormancy, adapted to meet the challenges of cold, deep snow and low food sources during winter, as well as immature cubs; but bears remain alert enough to be roused if needed. Bears do not eat, drink, or eliminate during this time. Not all bears hibernate, however, and in those that do, the length of hibernation depends on climate, food sources, and sex.

The illegal sale, primarily from poaching, of North American black and grizzly bear parts to Asian markets has increased even as the supply of Asian bears has decreased. Desirable parts include blood, bones, claws, paws, fat, meat, hides, teeth, and gallbladders.

American Black Bear (Ursus americanus)

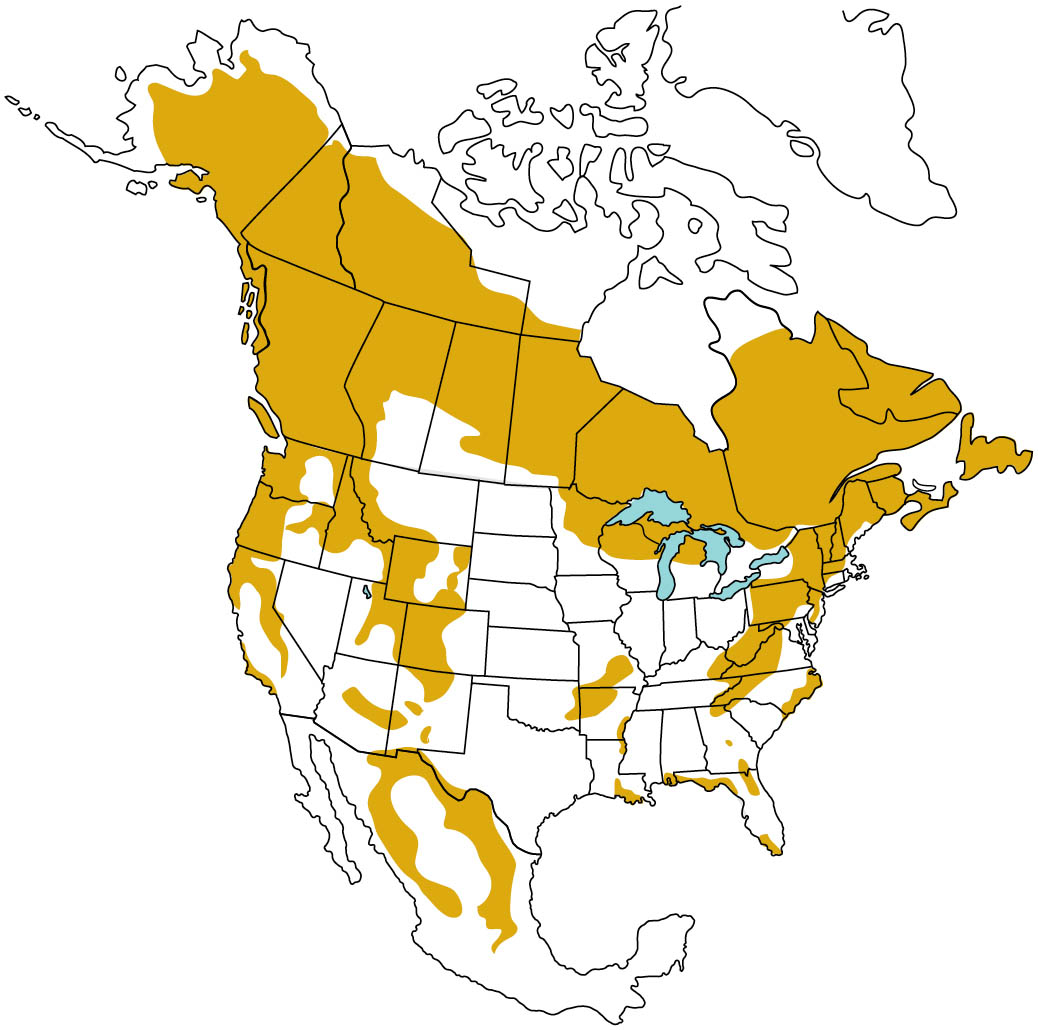

On the East Coast of North America, early explorers and colonists noted the abundant presence of bears. Black bears were found almost continent-wide, except the deserts of the Southwest and far northern Canada. American black bears are related to Asian black bears, but they are a separate species found only in North America. Regionally, the 17 black bear subspecies are often known by local names, such as the Florida, California, and Olympic black bears, or by colors, such as the cinnamon bear or the rare, blue-gray glacier bear. Worldwide, black bears are more numerous than all other bear species combined.

Since European explorers and colonists were well acquainted with bears, when the black bear was encountered he was simply called bear, an Old English word, and sometimes bruin, which was French. As the native people did previously, colonists widely hunted bears. Bear meat was commonly eaten, and the fat, or bear grease, was used for cooking, medicines, cosmetics, and waterproofing. More valuable than brown bearskins, black bear fur was desirable for its qualities of softness with a dense undercoat and longer, coarser outer hair. Despite the reality of the bear as a powerful predator and the horrors of bearbaiting, bears would come to be favorite animals in circuses, films, stories, and sports (as mascots).

Despite their powerful presence, bears are favorite fictional characters — including Winnie the Pooh, the original teddy bear, and Smokey Bear.

At the time of European colonization, the black bear population was estimated at about 500,000. Hunted extensively and faced with continual loss of their favored forested habitat, black bear populations were seriously reduced in most areas and exterminated in others. And yet today the numbers of black bears have actually increased to as much as 900,000. They are still absent from much of the center and southern areas of the country because of the lack of their preferred forest cover. However, they are again found in most states, although sometimes just as transients or in small isolated populations in national parks or recreation lands. Today their range overlaps with brown or grizzly bears in areas of the western United States and Canada. More bear–human interactions occur as people encroach on bear habitat for both recreation and housing. Unfortunately, bears easily adapt to human-provided food.

Description

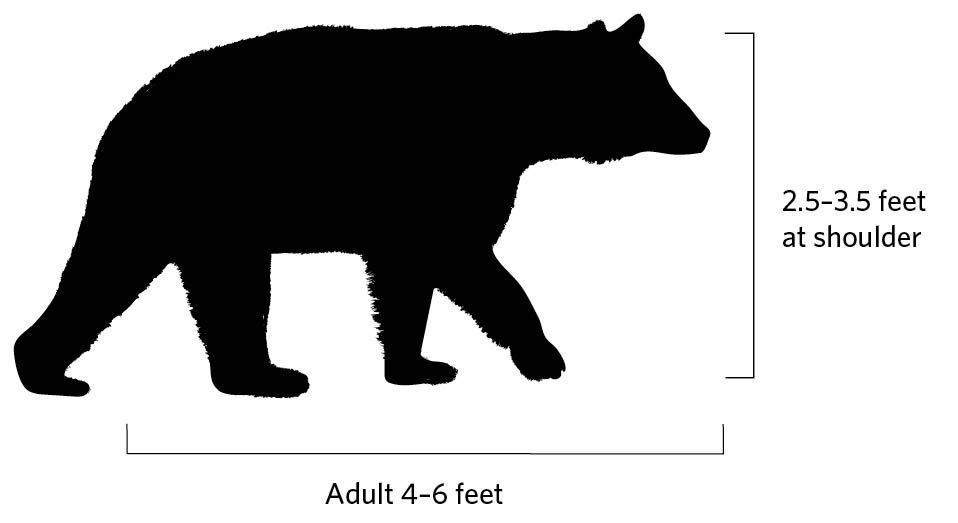

Smaller than either brown or polar bears, the average adult male black bear is 4 to 6 feet long, standing 2.5 to 3.5 feet at the shoulder, and weighing 250 to 400 pounds, with some individuals as high as 600 pounds. Females are smaller, averaging 150 pounds. The bear’s moderate-sized head has small eyes and round, erect ears, with a slightly roman-nosed and tapering muzzle. In profile, the black bear lacks the prominent shoulder hump of the grizzly and has a 3- to 6-inch tail. Black bears also have shorter, curved claws about 1 inch long.

East of the Mississippi River, 70 percent of the population is colored black. The muzzle is lighter brown or buff, and a white blaze on the chest is usually present at birth, although most fade away except in the Florida subspecies. About half of the populations of black bear subspecies in western areas are light to dark brown, cinnamon, or blond. In some specific areas, 95 percent of black bears are actually brown. Cubs can be different colors in the same litter, and their colors may change as they age, between shades of black and brown. Although rare, albino black bears also occur.

Black bears are excellent climbers and will climb trees to eat, to reach safety, and sometimes to hibernate. They climb less often when older and heavier. Black bears have a true walk, not a shuffle, and can run 25 to 30 mph for short distances. They are dexterous and agile, often seen walking on narrow logs. Black bears can pick up very small objects, as well as open screw-top jars and door latches.

Habitat and Behavior

Black bears prefer dense forests with understory brush, and they are found in hardwood or mixed nut trees, wet or dry forests, hardwood swamps on the eastern coast, coniferous forests of the Rockies and western coast, and chaparral or pinyon in the Southwest. In mountainous terrain, bears will move up and down slopes foraging in different seasons. They prefer remote or wilderness areas but will move out to meadows, timbered land, or other open areas in search of food. Black bears are also seen on roadsides, at landfills, and in picnic or camping areas.

The range size depends on habitat and food availability. Males can have ranges up to 1,000 square miles, which may overlap against several females with ranges of 6 to 19 square miles. Black bears use trees, poles, or wooden structures, marking with body rubs, shedding hair, claws, and teeth. The reason for these marks on “bear trees” is not completely established, but they may be dominance marks warning other bears away.

Primarily vegetarian and opportunistic, black bears are not active or skilled predators, consuming more carrion than hunted animals. They are more carnivorous in some areas such as the subarctic. They will steal carcasses from smaller predators but tend not to challenge larger brown bears, wolf packs, mountain lions, or wolverines. They may share carrion with a single coyote or wolf. When they do hunt, black bears will ambush or approach on four legs, using a blow from a front leg or a bite to disable or kill their prey. They will drag prey to secluded areas to consume it but may not cover it between feedings.

Black bears hibernate for 3 to 8 months, depending on climate and (for females) pregnancy. In northern areas, hibernation begins October to November and ends April to May. Bears may lose 25 to 40 percent of their weight during this time. They may hibernate in caves, hollow trees, culverts, or buildings, although most dens are dug under rocks or logs and windfalls of timber or brush. In areas without snow, black bears often den higher in tree cavities. In warmer weather, black bears may rouse to forage for food; in southern areas, bears may sleep for only a few days, except for pregnant females, which necessarily sleep for longer stretches.

Life Cycle

Breeding season is usually June to July, with cubs born in January to February. Black bear cubs weigh 40 to 60 pounds at 6 months. They reach sexual maturity at about 3.5 to 4 years. Females reach full size at age 4 or 5, which is sooner than males, which grow until they are 10 or older. The average life span in the wild is 18 years, but males can live to 30 and females as long as 40 years. About 60 percent of cubs survive their first year, with the losses due to other bears and predators, including birds of prey. As adults, predation by a grizzly bear or by wolf packs can occur. Ninety percent of adult deaths are attributable to hunting, trapping, or poaching; removal of nuisance animals; road accidents; or accidental poisoning.

Human Interaction

Black bears are easily conditioned to feed at garbage or trash areas, landfills, campsites, or direct human handouts. Since feeding causes increased aggression, the only response is removal. Relocation often doesn’t work, although “hard” releases with Karelian bear dogs and aggressive tactics seem to work better. Most removals actually result in the bear’s death.

Black bears also cause extensive damage to cabins, crops, beehives, timber, and orchard trees. They may challenge fishermen or hunters for food and steal carcasses from hunters. They will also eat birdseed, crops, and orchard and other fruits.

Black bears occasionally kill livestock: newborns or young animals, adult sheep, goats, hogs, and occasionally cattle or horses (which may only be clawed on the sides in escape). Black bears may confront dogs that harass or attack them.

Annual hunting kills at least 30,000 black bears, although bearskins are no longer commercially valuable due to low demand.

Legalities

Regulated and licensed game hunting is allowed for black bears in 28 states and most Canadian provinces. In protected states, authorities will remove problem bears and may provide compensation for damages. Most western states allow predation bears to be killed but may require a permit.

Black Bear Subspecies

Glacier bear (U. americanus emmonsii)

The glacier bear differs from other black bears by its blue or silvery gray color on the shoulder, back, and flank. They are primarily found in the coastal areas of southeastern Alaska, including Glacier Bay National Park. No population estimates are available.

Kermode bear (U. americanus kermodei)

The Kermode, or “spirit bear,” is found in the central and northern coastal areas of British Columbia. The white or cream color is found in about 10 percent of the population, while the rest are black. About 500 Kermode bears exist in the area, and they are fully protected.

Damage ID: American Black Bear

Prey on

Livestock, poultry, beehives

Time of day

Day, night, and dusk near humans

Method of Kill

- Hair, tracks, scat usually found in area of damage; vegetation smashed down around kill; distinctive musky odor of bear

- Carcasses showing deep teeth marks 1⁄2 inch in diameter on skull or neck and shoulders behind the ears; neck or spine broken; at times, nose or face deeply bitten

- Large claw marks of 1⁄2 inch on neck, shoulders, and sides of larger animals, either from striking or straddling

- Body opened, internal organs or udders on lactating females removed and eaten first, then hindquarters and other flesh fed on

- Skin of large prey torn off and inside out; skeleton often left intact and attached to skin; remains not scattered, unlike with wolves and coyotes.

- In open area, kill sometimes dragged into cover and covered with debris, bear returning at dusk to feed even as carcass decomposes

- Where stock is confined or unable to escape, 2 or 3 sheep killed

- Eggs or nestlings stolen

- Beehives and frames broken and scattered, bear returning until all eaten

- Corn or oat crops with large areas of smashed stalks and entire cob of corn eaten

- In orchards, bark clawed off to mark tree and to eat inner bark; branches torn off; bushes smashed

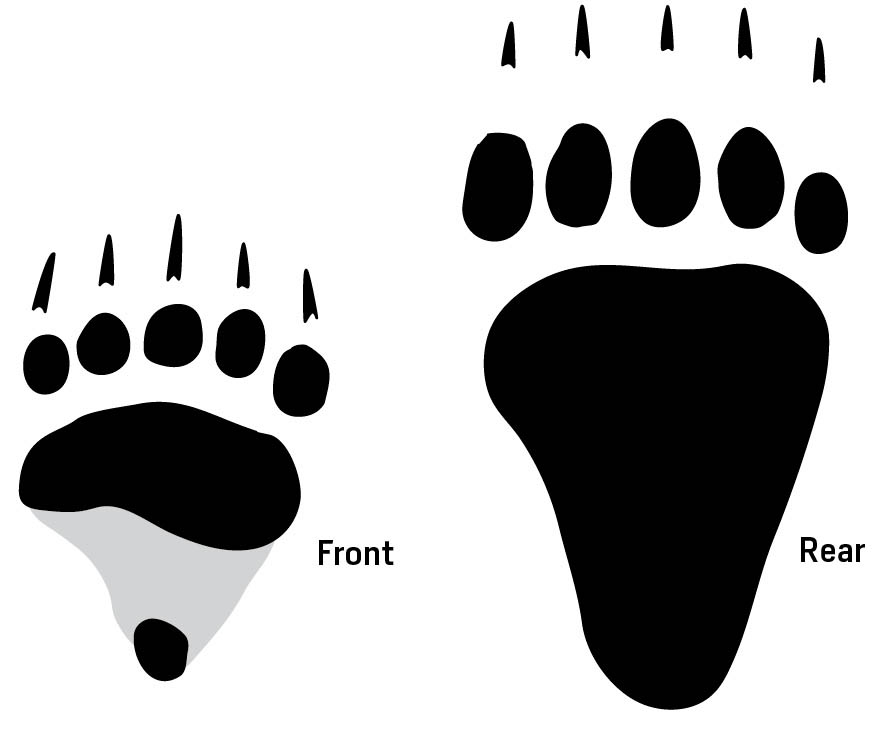

Track

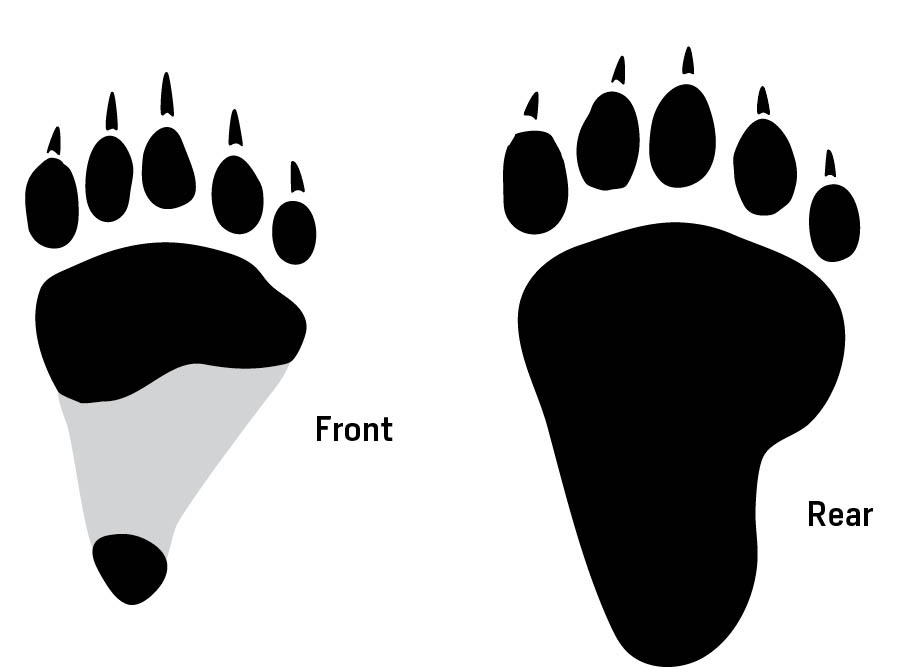

Front 33⁄4–8 inches long, 31⁄4–6 inches wide; rear 53⁄8–87⁄8 inches long, 31⁄2–6 inches wide. Rear foot resembles human footprint, slightly pigeon-toed. All 5 toes, claw marks, and front heel pad may or may not be visible; hair may obscure track details. Can be distinguished from grizzly bear by smaller size, shorter claw marks, and greater curve in arc of toes.

Gait

Walking stride 17–28 inches, may be direct-register or overstep; lope or gallop can be longer at 24–60 inches.

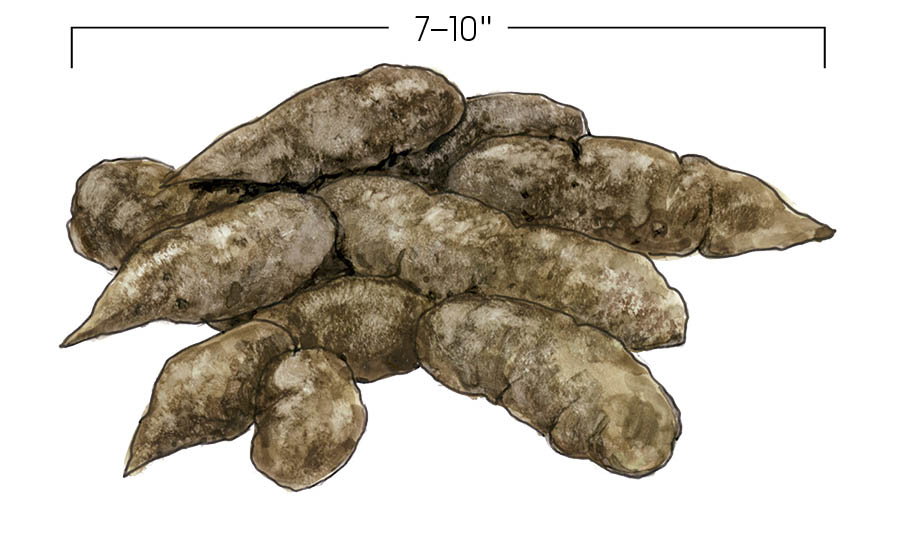

Scat

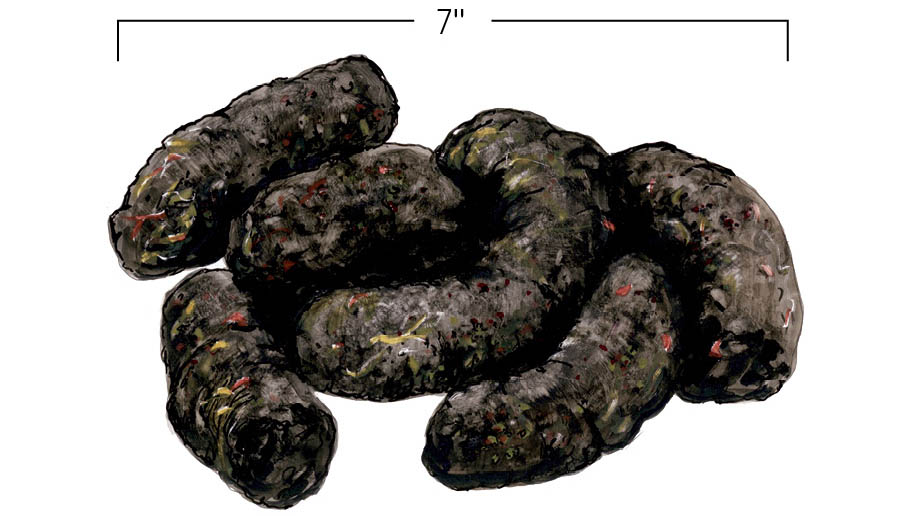

Cylindrical, thick, blunt ends, 7 inches long and 1 inch in diameter, usually coiled, black to brown color. Can resemble human feces except contents may reveal hair, bone, and plant fibers. Looser and softer if feeding on berries. Left uncovered at site of kill.

North American Grizzly or Brown Bear (Ursus arctos horribilis)

The large family of brown bears (Ursus arctos) is found in northern Europe and Asia, although now present only in small numbers. About 50,000 years ago the inland brown bear was believed to have migrated from Siberia into Alaska, later finding its way south into the deserts of the Southwest and Mexico, and east into the prairies of the Great Plains. Historical subspecies included the mainland brown bear, known as the grizzly; the Kodiak and peninsular bears found only in Alaska; and the extinct California (1922) and Mexican grizzlies (1960s). The exact genetic relationships of these subspecies are still being clarified through research.

The 19th-century population was estimated at 50,000 to 100,000 bears, which was dramatically reduced to some 400 bears in the lower 48 states by the 1970s, occupying less than 2 percent of their historical range. The brown bear population is stable in Alaska, with about 30,000 bears, and in Canada, with some 25,000 bears. In the lower 48 states, a recovering population of 1,500 to 1,800 bears is found in 4 of the 6 protected recovery ranges with possibly very small numbers elsewhere.

In 1804, the Lewis and Clark expedition first encountered the fabled “white bear” in the Dakotas, but the grizzly was well known by the native peoples, who clearly distinguished it from the black bear. The grizzly figured importantly in stories, traditions, and ceremonies; was found on totem poles; and was hunted for food and hides. At times called the Silvertip, grizzlies rapidly gained a fearsome reputation among the European settlers, with much attention paid to the largest examples of the population and sensationalized accounts. Indeed, after many encounters, Meriwether Lewis wrote that the grizzly was a “furious and formidable animal, and will frequently pursue the hunter when wounded.” Although one of the most dangerous and unpredictable predators in North America, grizzlies usually avoid human confrontations unless protecting their cubs or food, which they do with great ferociousness. Hunting and settlement reduced the grizzly population, with surviving bears retreating back into the less accessible and less developed areas of their former range. Logging, mining, and further development greatly pressured the survivors beginning in the early 20th century, reducing them to a fraction of their original population and range.

Under Endangered Species Act protection, grizzly recovery areas were established in the North Cascades, Washington; the Selkirk Mountains in Idaho and Washington; Cabinet Yaak in Montana and Idaho; the Northern Continental Divide in Montana; the Bitterroot Mountains in Idaho and Montana; and the Great Yellowstone area across the three states of Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana. While some populations remain very small, in the Great Yellowstone ecosystem the population has recovered from 136 animals in 1975 to perhaps as many as 700 bears. The Northern Continental Divide population is similar in size and moving out into agricultural and grassland areas. This expansion has prompted a controversial US Fish and Wildlife Service proposal to delist the grizzly bear outside of the national parks and to allow the states of Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming to manage bear hunting. No grizzly bears are present in the Bitterroot range, and the North Cascades population has fallen to fewer than 10 individuals. About 40 bears are found in Cabinet Yaak and another 80 in Selkirk.

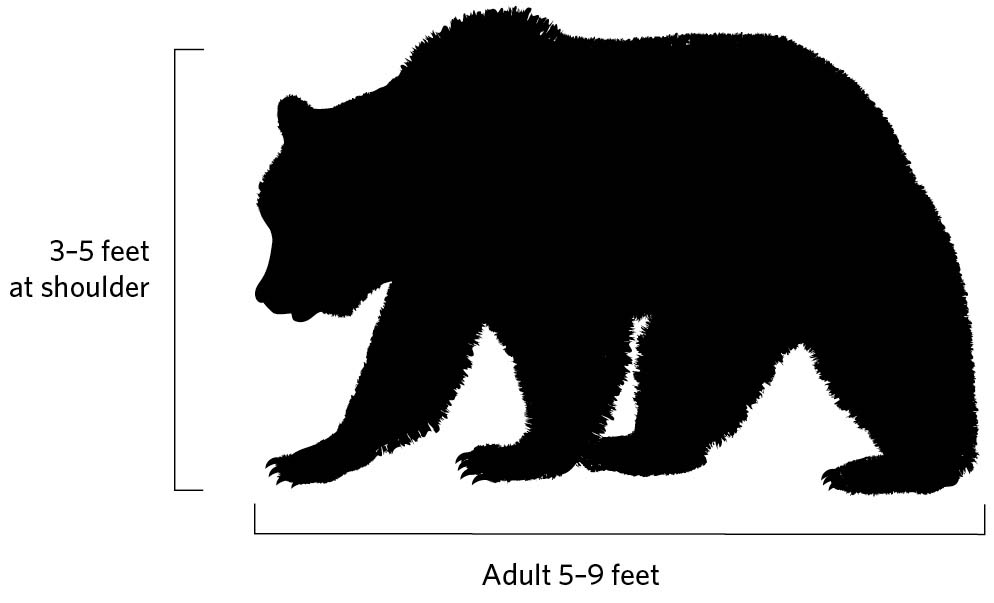

Description

Grizzly bears range from 175 to 1,300 pounds, 3 to 5 feet tall at the shoulder, and 5 to 9 feet long. Males average 400 to 790 pounds, and females 290 to 400 pounds. Coastal bears are larger because of a more abundant food source of fish and a longer feeding season. Interior bears in the northern areas are the smallest. The muscular shoulder hump is the highest point in the profile. It can appear even larger with the mane, especially when the hair rises in alarm. The hump is muscular and allows for great strength in the front legs and paws for both digging and hitting. Grizzly bears also have large, broad heads with a dished or concave profile and an upturned snout. Grizzly bears have a more powerful bite than the black bears. The slender front claws are 2 to 5 inches long and can be used as a tool to remove eggs or roe from a fish and for digging. The tail is 3 to 4.5 inches long.

Silver- or gold-colored tips, or grizzling, on the guard hairs on the hump, shoulders, and back gave rise to the name grizzly bear. This sheen can create different color patterns on the bears, which are found in shaded colors of pale or creamy blond, reddish blond, light brown, to very dark brown that can appear nearly black. The legs generally appear darker. Darker colors are more frequent in forested areas, with lighter colors in the tundra. Very dark bears are generally not as grizzled. Cubs often have a white collar.

Grizzly bears are extremely strong. They can deliver powerful blows with front legs and paws, drag very heavy weights uphill, move huge rocks and carcasses, dig large holes, and tear down logs or siding. Although generally poor climbers because of their weight and long claws, the cubs or young bears can climb, and the adults can use low branches as ladders to get up a tree. They have a slow, shuffling walk but a fast and silent run of 35 to 40 mph. They also have good endurance and are excellent swimmers.

Habitat and Behavior

Worldwide, brown bears have adapted to a wide variety of habitats. In Alaska and coastal areas, they are found more often near the ocean or rivers. Using dense cover for sheltering during the day, grizzlies also inhabit old and boreal forests, higher elevations, and more open areas such as meadows or even tundra. Males establish ranges from 100 to 1,500 square miles, with female ranges smaller. The largest ranges are in the Rocky Mountains, boreal forests, and arctic areas, with the smallest in coastal areas or on islands. Ranges overlap, and the bears do not actively defend a territory. They do not tend to use the same areas as the black bears.

Grizzlies mark and rub on trees or other objects to communicate their presence, and they also use posturing and vocalizations. They will group together at food sources, defending their dominance, with old males and females with young the most aggressive. Grizzlies will travel long distances for seasonal food sources, which often brings them into increased contact with humans. Grizzlies are also more aggressive than black bears in defense of themselves, their prey, or cubs and are inclined to stand and fight.

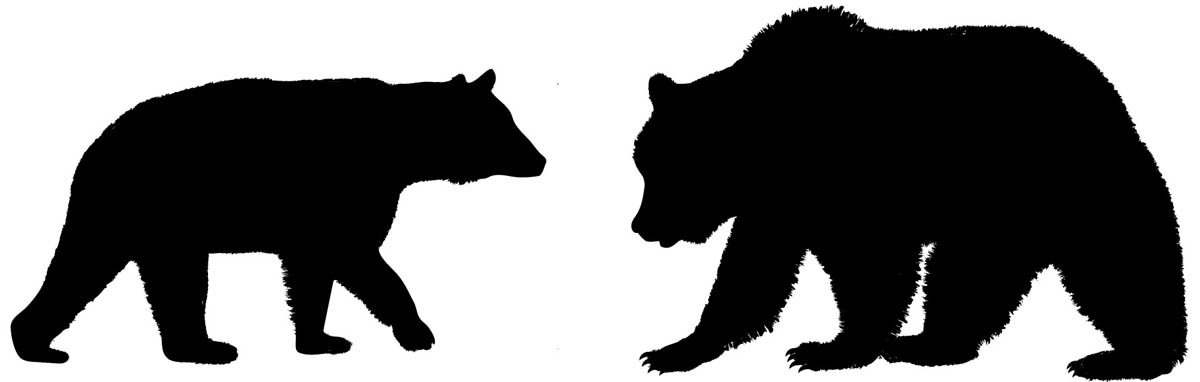

Black Bear or Grizzly?

At a distance bears always appear larger than they actually are because of their dense fur and overall bulky appearance. Excitement can also make identification difficult! Although they may be of similar size or weight, depending on age, black bears and brown or grizzly bears have noticeable differences.

Black

- Smaller and less stocky or bulky

- Rump higher in profile

- Straight face profile and long muzzle, usually colored lighter

- Taller, less round ears, set higher on head

- Short, sharply curved claws 1 to 2 inches long

- Black color east of Mississippi River

- Hind foot track shows spaces between toes and shorter claw marks; front toes more rounded into an arc than the grizzly

Brown/Grizzly

- Larger and more massive overall

- Hump higher in profile

- Very large, broad forehead with dished profile, long upturned muzzle

- Short, rounded ears

- Long, curved claws 2 to 4 inches long, especially on front paws

- Longer and shaggier fur with distinctive mane on back of head and neck

- Blond to dark brown color with frosted hair tips

- Hind foot track shows toes touching each other in a straight line and claw marks extending farther out in front; front track more square than on black bear

Grizzly bears are omnivores, with their diet often falling between the primarily herbivore black bears and the nearly carnivorous polar bears. Grizzlies will claim carcasses killed by a mountain lion, smaller packs of coyotes or wolves, or a black bear. They generally chase away other predators but occasionally kill wolves, mountain lions, or black bears.

Grizzlies are important predators of elk and moose calves. They will also take large animals such as deer, caribou, bighorn sheep, mountain goats, bison, moose, elk, or muskoxen. Grizzlies often take advantage of animals that are infirm or floundering in snow. They will run down or charge their prey, knocking them over with a blow or blows, and then bite the head or neck. Near the coast, grizzlies eat fish, clams, dead whales, seals, and sea lions. Yellowstone bears have become more predatory with the availability of ungulate calves and adults, bison, winterkilled carcasses, and the occasional sheep or cow. In the Rocky Mountains, grizzlies also eat grasses, legumes, berries, insects, ants and bees, and moth larvae.

Grizzlies will gain up to 400 pounds before a hibernation of 5 to 7 months. They may den as early as September at higher altitudes. Grizzlies often dig a tunnel entrance into a steep sheltered bank or slope to avoid flooding, using the roots of a large rock to help support the sides and roof of a sleeping chamber. Deep snow provides insulation. Grizzlies frequently return to the same area and den. Coastal grizzlies will often hibernate for less time and may use a hollow tree. Grizzlies may not hibernate if food is plentiful during winter, although pregnant females do hibernate. Females will emerge later than males in April or May.

Life Cycle

Grizzlies breed mid-May to mid-July, then go their separate ways. The female dens in late October to November, with the cubs born in January to March. Weighing 1 pound at birth, cubs will weigh 125 to 175 pounds at 1 year. Eighty percent of cubs survive their first year in Alaska or the Yukon, but in the Yellowstone area subadults have only a 40 percent survival. The young are vulnerable to other bears and natural mortality. Cubs stay with their mother 2 or more years, and she fiercely protects them. Grizzly bear mothers are also known to adopt orphaned cubs. Young females often remain in or near the mother’s range, while young males are driven away into less desirable areas. Grizzlies achieve sexual maturity at ages 5 to 6, although males continue growing until age 14. Average life span is 20 to 25 years, but they may live up to age 40. Causes of death for bears over the age of 1 are hunting, poaching, or targeting removal. More rarely, young bears die by road or natural accidents, or attacks by another brown bear, wolf, or mountain lion.

Human Interaction

In the lower 48 states, grizzlies are an important keystone predator for ungulate populations. They may visit landfills; damage orchards, beehives, or buildings; and kill livestock. They also challenge hunters or fishermen and damage fishing nets.

Defenders of Wildlife offers funding for electric fencing to protect gardens, orchards, beehives, livestock, and poultry, and to allow backcountry recreation. The group also supports projects to implement bear-resistant garbage and food storage systems in communities and campgrounds.

Legal Issues

Grizzlies are protected as a Threatened species in the lower 48 states. To shoot them is illegal except in self-defense, in defense of others, or by authorities. Regulated game hunting is allowed in some areas of Alaska and Canada.

Montana will compensate ranchers for verified livestock losses, as the Defenders of Wildlife do in Idaho, Wyoming, and Washington.

Other Bears

Kodiak Brown Bear

(Ursus middendorffi)

The largest of the brown bears, the Kodiak may have evolved from a separate migration of Eurasian brown bears into Alaska, where they were isolated since the last Ice Age. They are found today only on the Kodiak Archipelago islands. As of 2005, the population was estimated at about 3,500. Colored blond to dark brown, males can be 8 feet long, stand up nearly to 10 feet, and weigh up to 1,500 pounds, with females 20 to 30 percent smaller.

Polar Bear

(Ursus maritimus)

Not only the largest members of the bear family, polar bears are the largest land carnivores. Polar bears are native to the Arctic Circle, living and hunting on the edges of the pack ice through the long winter, traveling up to several thousand miles yearly. Nearly completely carnivorous and strong swimmers, polar bears hunt seals, walruses, Beluga whales, narwhals, small mammals, and birds such as sea ducks. During the months of summer ice melt, many bears are confined to the coastal areas or find resting places farther inland. Although they often do not eat, drink, or eliminate during the summer, males and nonbreeding females do not hibernate. Pregnant females eat through the summer and fall, entering dens in late fall where they remain until late winter or early spring. The dens may be found inland, near the coast, or even on ice floes. Cubs remain with their mothers for about 30 months.

Males average between 500 to 900 pounds, with females about half their size. Large male polar bears can weigh 1,300 to 1,700 pounds. They are massive in appearance, with a long neck and large feet. The dense double coat is white but may appear somewhat yellow, gray, or brown at various times.

Most interactions with humans occur during the summer months. Polar bears will also forage around landfills, construction, or hunting sites. Because polar bears are a protected species, hunting is not legal in Alaska but is regulated in Canada. The polar bear population is estimated at 20,000 to 25,000 worldwide; however, with the continued loss of sea ice due to climate change, experts believe the survival of polar bears is gravely threatened. It is unlikely that the population could find sufficient food by switching to geese or other animals.

Hybrid Bears

In 2006 in the Northwest Territory, a hunter shot a bear that proved to be a hybrid between a polar bear and a grizzly bear, and other hybrids have been confirmed as well. On the ABC Islands (Admiralty, Baranof, and Chichagof), a population of bears has a genetic structure that reflects both brown and polar bear contributions. With the loss of polar bear habitat, more hybrid bears may occur.

While brown and black bears have crossbred in captivity, no evidence supports that this occurs in the wild.

Dealing with Bears

Homes and Yards

Talk to your neighbors and try to cooperatively use prevention techniques. Many municipalities have bear regulations as well. There must be absolutely no food handouts or access to garbage.

If you spot a bear in or around the yard, stay inside, bring pets indoors, and do not harass. The bear will move on unless it finds food. Alert neighbors and local authorities if needed. Report any habituated or problem bears, which may be hazed or removed by authorities. Around homes or cabins in bear country, remain aware of your surroundings and move cautiously at vulnerable times and in areas near cover.

All the prevention techniques used with the more common black bear are applicable for grizzlies.

- Clear 150 feet around human and animal areas. Trim tree branches 15 feet from buildings.

- Locate crop areas 150 feet away from protective cover.

- Harvest ripe fruit and vegetables, clear any fallen fruit from ground, and remove garden refuse.

- Don’t plant bear-friendly food plants. Water is also an attractant in arid climates.

- Feed pets inside or bring empty bowls inside after feeding.

- Backyard chickens or pets require secure animal housing, including a top or roof and possibly an electric barrier. Backyard chickens should be closed in at night.

- Don’t use birdseed and suet feeders from March through November. Some people bring feeders in at night or make sure they are hung at least 10 feet tall and away from trees or buildings. Equip bird feeders with large spill pans to prevent seed from falling to the ground. Clean any spilled seed.

- Secure pet food and birdseed — don’t store on decks or porches.

- Use bear-proof trash containers or keep trash inside a secure building or specially built outbuildings. Use caution with highly attractive-smelling garbage: rinse all used food containers, wrap securely, or freeze and place out right before collection. Be very careful of fish parts and meat scraps.

- Clean and store BBQ grills, outdoor kitchens, and fish-cleaning stations. Outdoor refrigerators and coolers attract bears.

- Spray cans and other food preparation areas with ammonia, bleach, or powerful disinfectant.

- Securely close all windows, doors, garages, and pet doors especially at night. Buy reinforced doors if needed. Use round doorknobs or very secure latches. Bears can easily climb stairs, deck railings, and so forth.

- To prevent climbing, use sections of 1 × 4 boards, 4 feet long, equipped with protruding screws or nails every 6 inches. Wire at least 4 of these boards around any tree to prevent climbing.

- Do not store food or trash in vehicles, which bears can open or damage.

- Use night lights, strobes, motion-detection lights, or loud sounds. Move scare devices every other day to prevent habituation.

- Use livestock guardian dogs (LGDs). Bears do not habituate to loud barking dogs.

- Take special precautions with cabins: reinforce windows and doors; clean out all food and scented items or store in bear boxes; disinfect outside cooking areas and tables. Prevent ants or bees from nesting in siding to avoid property damage.

- Avoid scented items. Bears are attracted to certain aromas: cedar, pine, tarpaper, petroleum products, starter fluid, turpentine, kerosene, and citronella.

Livestock Husbandry

Most livestock predation occurs in spring after bears emerge from hibernation and stock is giving birth.

- Securely confine or protect animals giving birth.

- Remove or bury all afterbirth and carcass materials.

- Locate poultry and livestock housing, beehives, and pet kennels 150 feet from woods or areas of cover. Build securely and surround with an electric barrier.

- Place unwelcome mats either studded with nails or electric in front of windows and doors.

- Be aware that an LGD may be able to harass or frighten away a bear, but a bear can easily turn on the dog. Two LGDs are recommended for bear protection.

Fencing

- Electric wires increase the effectiveness of any fence. Teach bears to respect electric fencing by luring them to it with bacon or empty cans that contained fish.

- To protect a beehive, orchard, compost pile, or garden, erect an electric fence 3 feet tall, with wires spaced 10 inches apart and a bottom wire 6 inches from the ground.

- Use electric wire or tape fencing to protect poultry or stock.

- Nonelectric fencing should be 6 feet tall — chain link, heavy woven wire, or livestock panels — with a 24-inch outward extension of barbed or electric wire at top.

- If needed, install a 2-foot outward apron of chain link or steel mesh attached to the fence and staked down to prevent digging.

- Group beehives near each other, surrounded by 6-foot-tall livestock panels or 6-inch square mesh fencing, with an additional layer of temporary electric fencing around that. Beehives can also be placed on 15- to 20-foot-tall platforms with support poles wrapped in sheet metal.

Additional Fence Considerations for Grizzly Bears

- Temporary electric fencing is recommended for backcountry camping and hunting or stock camps in grizzly country.

- Recommended exclusion fencing for grizzly bears is heavy chain link or woven wire 8 feet high, buried 2 feet belowground, with metal extensions outward at the top with barbed or electrified wire.

- Electric wire fences should be 9 wires, beginning 4 inches from the ground.

- The Defenders of Wildlife will compensate 50 percent of the cost of electric fencing used to prevent grizzly bear access to attractants, including garbage, orchards, or livestock in eligible counties in Washington, Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming (defenders.org).

Dealing with Bear Encounters

Keep in mind that bears are not generally aggressive toward humans. A bear sighting is also unusual, as most bears are reclusive, although they may be curious. An actual bear attack is extremely rare. Throughout the 20th century, there was an average of 1 fatal bear attack per year, equally due to black and grizzly bears. An increase in fatalities was seen during the 1960s and ’70s, mainly due to habituated bears. In the 21st century, fatalities are again increasing slightly, with about 2 deaths per year. Half of these deaths (15) were in Canada, 3 in Alaska, 2 in Tennessee, and single deaths in California, Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania, and Utah.

If your home or ranch is in bear country, you should be prepared for encounters. Otherwise, outside of Alaska or Canada, the majority of sightings are near national parks, recreation areas, campgrounds, or rural homes where bears have become habituated to humans or their food sources. Bears are also more active during droughts or poor forage years and before and after hibernating, as are young males without a home range. True predatory attacks are very rare.

While similarities are seen between black and brown or grizzly bear encounters, some important differences can also be seen. Knowing how to react if you sight a bear prevents the vast number of encounters from becoming dangerous. Several proven techniques and strategies will also help keep you safe.

Black bears tend to be shy or timid; however, you are far more likely to encounter one due to their widespread presence. Generally, interactions occur because a black bear becomes habituated to humans or human-provided food sources. Other encounters occur when bears are strongly motivated by hunger. Female black bears do not protect cubs as strongly as grizzlies but will react to a perceived threat by humans. Fortunately, even in the case of a physical encounter resulting in injuries, 90 percent are only minor bites, scratches, or bruises.

Grizzly encounters are less common in the lower 48 states because of the bears’ very low population. Grizzly bears are more unpredictable and aggressive in their response to perceived challenges to their food or protection of their cubs. Grizzlies will also challenge a fisherman or a hunter for their catch or cache. Their larger size is also a factor.

Bear Spray

The single most important defensive strategy in bear country is to carry bear spray.

Use real bear spray, not pepper spray or Mace. Although the use of spray should be your last resort, it is essential that you know how to use it properly. Used correctly, bear spray is effective in more than 98 percent of attacks, although somewhat less effective with black bears than with grizzlies. Shooting with a gun has proved to be less effective than bear spray because a wounded bear is significantly more dangerous. Defense with a gun in a bear attack is effective less than 50 percent of the time.

Cautions

- Try to stay out of the spray when using.

- Handle carefully, as bear spray may cause blindness at very close range.

- Exercise great care around children.

- Keep in mind that you cannot carry large cans of bear spray on aircraft.

Each person in a group should carry a large can or two (with protective zip tie removed but safety clip on) in a holster or belt outside of clothing or pack. Use with 2 hands, when the bear is from 30 to 60 feet away, spraying short blasts in a side-to-side motion. If the bear is very close, aim for the eyes. Aim lower than the bear’s head as the spray will rise. If the bear continues to approach, spray again. Know the capacity of your spray and how many 2- or 3-second bursts you have available.

Canisters with inert ingredients are available for practicing. Learn more about using bear spray at the Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee website (igbconline.org).

Bear-Watching Guidelines

Wild bears are one of the attractions of national parks. However, habituation can be dangerous to bears; they will be destroyed if they become aggressive. To safely view bears and not endanger them or yourself, follow these guidelines:

- Park safely.

- Never feed or entice a bear.

- View bears safely through binoculars or telephoto lenses.

- Stay in your vehicle in national parks, unless the bear is more than 100 yards away.

- Remain very close to your vehicle for safety, and do not let children roam away from you.

- If other people crowd, corner, or behave inappropriately to a bear, it may feel threatened and react. Leave potentially dangerous situations. You are responsible for your own safety in bear country.

Recreation in Bear Country

Remain alert to bear signs:

- Tracks

- Scat

- Claw-marked trees, stripped bark, torn-apart logs

- Digging or large overturned rocks, possibly with claw marks

- Areas of trampled ground or brush

- Oval-shaped day beds

- Signs a carcass may be nearby — odor, fish, fur, or meat scraps on the ground; debris-covered humps on ground; or circling birds

Hiking

- Do not hike alone. Travel in groups of at least 2 or 3; groups of 6 or more are safer. By far, most attacks are to solitary people.

- Keep children between adults. Teach them that running ahead, lagging behind, screaming, and running are very dangerous.

- Before hiking, consult authorities for the latest bear activity and areas closed for bear management.

- Stay alert for bear signs. Go back or widely detour around any bear signs.

- Make noise, talk, or sing. Carry a safety whistle, air horn, and other noisemakers. Some experts believe bears associate bear bells with food.

- Carry bear spray and a fixed-blade knife.

- Travel in daylight; midday is best. Bears do use trails at night and may during the day as well.

- Travel in the open whenever possible and use care near blind corners, waterways, animal trails, loud rushing water, or dense brush. Avoid berry patches and other food sources.

- Only carry dry, sealed foods and use non-scented products.

- Do not bring dogs. Off-leash dogs entice bears back to humans. Leashed dogs are also a threat since barking dogs are seen as aggressive to bears.

- Do not set down your food, pack, or gear and walk away.

Biking, Jogging, Skiing

Moving rapidly and quietly, bicyclists, skiers, and joggers often surprise bears, who may then chase them. Riders on horseback have never been attacked, although bears may spook horses and cause riders to fall. Follow all the hiking guidelines. Avoid dawn and dusk, when bears are likely to be along roads, trails, or streams. Carry bear spray, make noise, and occasionally use safety whistles or air horns. Stay alert, especially on windy days, around blind curves, or in dense vegetation. Don’t wear earphones.

Camping, Fishing, or Hunting

Always check with authorities as to bear presence. Bears may be habituated to campsites, trails, or fishing sites. Choose an open area away from food sources, 150 feet from cover, streams, or possible animal trails or pathways. Avoid any seasonal feeding or denning areas.

- Don’t camp where bear signs are present or at dirty sites. Always disinfect tables, benches, and tents.

- Don’t sleep outside your tent.

- Use flashlights after dark.

- Carry bear spray at all times or keep very close, even at night.

- Freeze-dried and other nonodorous foods are preferable. Food needs to be well packaged in airtight containers. Wrap or dispose of all food waste appropriately. Do not bury.

- The sleeping area, tent, sleeping bags, clothes, packs should be free from food and odors. Use scent-free toiletries. Handle menstrual products with care and dispose of appropriately. (Some experts recommend the use of tampons only.)

- Cook, clean dishes, store food (human, dog, or horse) and fish or game meat at least 100 feet, preferably 300 feet, downwind from sleeping area.

- Use bear-proof containers, including provided bear boxes or storage, or hang food. Food should be suspended 10 feet high and 4 feet away from a tree or pole in airtight containers or between trees 100 yards apart. Platforms 15 to 20 feet tall, with metal-wrapped support poles, may also be available.

- If a bear approaches a campsite, people should group together and make as much noise as possible. Children can be sent inside a tent or camper.

- If you hear a bear outside your tent, start talking calmly, turn on lights, and get your bear spray ready. If the bear claws at the sides of the tent or bites at you, treat it as an attack and fight back loudly and aggressively.

When camping in vehicles, follow the practices listed above and all campsite regulations. Keep children close and dogs on leashes. Keep bear spray close and use flashlights after dark. Some campgrounds do not allow food storage in vehicles and require campers to use bear boxes or hang food. Bears can damage or break into cars, trucks, and RVs.

Bear-Resistant Storage Required

Many federal and state recreation areas require appropriate storage of human and animal food, garbage, cooking utensils, stoves, and scented articles. For a list of certified canisters, panniers, and coolers, see igbconline.org.

Hunting and Fishing Guidelines

- Be aware that using elk calls or bugles may attract bears.

- Field-dress game animals immediately, if possible. Move gut pile 100 yards from carcass, at least 100 yards from trails. If you can’t pack out a meat carcass, hang properly. Be alert for bears near the carcass at all times. If you return, approach from upwind. Do not defend a carcass from a bear.

- Do not leave fish entrails on the side of a lake or stream — sink them in deep water. Store fish properly.

- Remove clothing used for cooking or cleaning fish or meat.

- Do not burn or bury scraps or waste. Carry out well-wrapped garbage or dispose of it in approved bear-proof containers.

- Use a perimeter alarm system and/or portable electric fence. Portable electric fencing is recommended for hunting camps, long-term camps for livestock or other field workers, or any camp in areas of high bear density.

Bear Attack: Defending Yourself

A bear that approaches silently, is staring, and is walking on all 4 legs is more likely to be predatory. Immediately respond aggressively and use bear spray. The bear may circle or reappear as you retreat, so remain very alert.

Try to identify the bear as a black or a grizzly, since your response to an aggressive threat will differ. Follow the same protocol for both, however, up to the point that an attack is imminent.

- Don’t approach a bear or a cub. Mothers usually send cubs up a tree and then retreat or attempt a bluff. Cubs may moan or wail in fear.

- Don’t throw or drop food.

If the bear seems unaware of you, yawning, or not looking at you, do not run but move away quietly and keep watching it. Avoid eye contact. Don’t block the bear’s escape route. Although bears often stand on hind legs to get a better view or smell, they attack on all fours. Standing up is not a threat.

- Hold bear spray in your hand.

- Keep your pack on as protection.

- Pick up small children so they won’t run.

If a bear approaches as you back away, make yourself larger, slowly wave your hands or sticks, and talk in a low voice. Don’t say the word “bear” because people who feed bears often say “Here, bear.”

- Don’t throw things at the bear, but you can drop objects (not food) down or away to distract it.

- Continue to back away. Don’t run unless safety is extremely close. At 35 to 40 mph, bears can outrun you uphill or downhill. Don’t climb a tree or attempt to swim away. Black bears and smaller grizzly bears can climb trees. Larger bears can ladder up trees, reach high into trees, or knock you out of a tree. Bears are excellent swimmers that hunt in water.

If the bear continues to approach, making snorts, grunts, chomping, snapping, or deep-throated pulsing sounds, or if it makes mock charges:

- Make loud noises, clap, yell, whistle, blow an air horn, raise your arms, and stare at the bear. If in a group, stand shoulder to shoulder.

- Use bear spray at a distance of 40 to 50 feet away.

- If the bear attacks, continue to use bear spray and fight back aggressively using your hands or objects. Aim for the bear’s eyes.

Grizzly Bear Attack

At the point of an actual attack by a grizzly bear, try to judge whether the bear is defensive or predatory. A defensive attack by a grizzly can occur when the bear is surprised, defending a carcass, or protecting her cubs. If your aggressive response and use of bear spray is not effective, you must “play dead” until the bear believes the threat has ended:

- Lie on your stomach with your hands protecting your neck, and brace yourself with your elbows to resist being turned over. Your backpack can offer some protection.

- Draw up your legs, lie still, and remain quiet.

- When the bear leaves, stay immobile as long as possible. If it is nearby, the bear may react again to movement.

If the bear attacks, continue to use bear spray at his eyes, and fight back aggressively using your hands or objects — a fixed-blade camping or hunting knife, a walking stick, a heavy stick, or a rock. Aim for the eyes.

Damage ID: Grizzly Bear

Prey on

Livestock, poultry, beehives

Time of day

Day

Method of Kill

- Distinctive odor, described as musky or musty; claw marks or hair rubbed off on brush or bark; scat evident

- Larger livestock run at and slashed from the rear, pulled and held down; head or neck bitten, skull possibly crushed and back or neck broken

- Claw marks on animal’s face or shoulders from slashing blows or bites delivered while grasped by bear

- Small animals bitten through forehead, head, or neck; smallest animals almost entirely eaten, leaving only rumen, skin, and large bones

- Carcass held by bear with its feet, underside torn open, heart, liver, and udders eaten; rumen and intestines spread out on ground

- Hide sometimes skinned; fat layers may be eaten; a great quantity of the meat eaten.

- If killed in open area, carcass may be dragged to a more secluded area; may be covered while bear rests nearby.

- Beehives broken and scattered, bear returning until all is eaten

Tracks

Front 7–131⁄2 inches long, 5–83⁄4 inches wide; rear 81⁄4–14 inches long, 45⁄8–81⁄2 inches wide. Hind looks like human footprint. Tracks appear pigeon-toed. Claw marks are visible and may extend out from front paw 4 inches. Toes in straighter line than black bear’s.

Gait

Usually amble or pace at the walk, moving limbs on one side of the body together, stride 25–33 inches. May also direct-register or overstep. Lope or gallop rarer.

Scat

Blunt or short taper; 7–10 inches long and 11⁄2–2 inches in diameter; left uncovered at site of a kill; black to brown color; can resemble human feces, except contains hair and bones.