Introduction

Since at least the middle of the 1800s, since long before modern national accounting was developed, it has been universally recognized that a characteristic of developed capitalist economies is that periods of output growth alternate with periods of contraction. Originally called “trade cycles,” these repeating expansions and contractions came to be known as “business cycles” by the second half of the 20th century. The term is somewhat unfortunate in the sense that there is neither theoretical nor empirical support for these expansions/contractions having the regularity of repetition suggested by the word “cycle,” but it is nevertheless the term that has come to be universally used for this characteristic of capitalism.

Marxist economics understands capitalism to be driven by the self-expansive nature of capital, effected through its pursuit of profits.1 This makes both the theoretical and empirical study of the rate of profit central to Marxism’s understanding of the functioning of the capitalist system and, of particular importance for this article, to the behavior of its business cycles.

The connection of the rate of profit to business cycle fluctuations in the growth of output occurs primarily through several influences on investment, both as a “push” and a “pull.” On the one hand, given that the driving force of capitalism is the pursuit of profits, higher rates of profit constitute greater motivation to invest. This causes an increased rate of growth of output in two ways. First, investment is the most variable of the three standard components of total demand: consumption, government spending and investment. Any increases in demand usually, excepting a rigid supply constraint, increases output and does so beyond its own magnitude through the well-known multiplier effect. Second, real investment occurs through new capital equipment (or sometimes directly through improving the process of production) with increased labor productivity, again increasing output. On the other hand, increased profits provide an increased amount of capital available to be invested, to be thrown back into the circuits of capital. However, the post-2009 weak expansion in the U.S. is a striking current reminder that this push-effect of increased available capital to invest has a complex relation to the profit rate. Despite large amounts of capital available for reinvestment because of the high rates of profits on existing productive capital, real investment and hence growth has remained low because capital does not perceive opportunities for high profits on new productive investment. Hence capital is simply “sitting on” large reserves of potentially investable capital or investing them only in financial assets, waiting for conditions to change to where it can get higher rates of return on real investment, thus yielding the current weak output growth.

While Marx and Engels and subsequent Marxists for almost a century certainly noted that business cycles existed, their discussions of them were almost always only in relation to their central concern of capitalist crises.2 Two positions were dominant in the popular Marxist discourse. In the one, each business cycle was a crisis, and as capitalism continued to develop and in particular as capital continued to accumulate, each business cycle would have a tendency to be a more and more severe crisis. Eventually this would generate a crisis severe enough so that the working class, given its particular state of organization and level of consciousness, would act in response to the crisis and overturn capitalism. In the other common Marxist argument, business cycles were not considered to be crises. Rather, they were understood to be the way capitalism (temporarily) resolves its crises, by liquidating enough capital to create the conditions for the resumption of the accumulation of capital. The point here is not that these two positions are irreconcilable, which they aren’t. The point is rather that in the late 1970s when the dominant modern frame for Marxist empirical/theoretical considerations of business cycles that this article will discuss was first developed, the basic nature of the relation between business cycles and crisis theory was a contested issue. From this the frame that was developed then was consciously intended to address both business cycles and crisis theory, and almost all Marxist works on business cycles continue to today to have their implications for capitalist crises as an important concern. While the business cycles and crises must not be misunderstood as being a single issue, it remains true today that an article about “Marxist business cycle theories” cannot be written without reference to Marxist crisis theories.

Marxist Business Cycle Theories

As noted in the introduction, almost all the early work that was to later become the basis for Marxist business cycle theories was done as crisis theories. As such, the focus was on the fall in the rate of profit in each cycle. To have a cycle, one of course needs to also explain what can cause a falling profit rate to reverse and start rising. Basically each theory of the cause for a falling rate of profit when extended to business cycles just went on to add that the cyclical upturns were caused by a reversal of the conditions that caused the cyclical downturns, as will be further discussed below. Hence the starting point for the modern Marxist discussion of business cycles was the then-current Marxist theories of crises, theories of a falling rate of profit.

Early Marxist crisis theories developed three different causal explanations for the falling rate of profit:3 rising organic composition of capital, overproduction/underconsumption, and a wage squeeze. In his seminal papers for modern Marxist business cycle research, Weisskopf (1978, 1979)4 introduced the following simple formula as useful for empirically/theoretically considering the dominant crisis theories and then discussed at length what it indicated about those theories.

where r is the rate of profit, P is total profits, Y is net output, K is the capital stock and Y* is the potential output that could be created with the existing K. We will call the terms P/Y the profit share, Y/Y* the capacity utilization and Y*/K the potential output-capital ratio.

The basic concept of the rising organic composition of capital argument is that over time capitalism keeps increasing the amount of capital it uses for a given amount of labor and therefore for a given potential output. Equation 1 shows that if the direct effect of such an increase in K on the potential output-capital term (Y*/K) is greater than any secondary effects the change in K causes in the terms P/Y and Y/Y*, the profit rate will fall. Similarly, overproduction/underconsumption5 implies that there is not enough demand for producers to supply the output that they could create, and that therefore they will lower production below potential production causing a fall in the rate of profit from a decline in the actual capacity utilization (Y/Y*). Finally, if we consider profits broadly so they are everything not paid to workers as wages (so taxes, rents, interest payments and so on are all just considered transfers of profits from where they are produced to someone else), then by definition net output is just the sum of wages and profits, Y = W + P. With this we see that if total wages (W) increase6 the rate of profit falls from a decrease in the profit share (P/Y).

As Weisskopf pointed out in his original paper, all the various concepts (or any combinations of them) were logically consistent with driving business cycles. What actually drove the various cycles (or their secular trend) “can therefore only be made with reference to specific historical circumstances, and by means of an analysis of the empirical evidence.” (Weisskopf 1978, 256) As with any scientific theory about the real world, once one has eliminated logically inconsistent alternatives, further theoretical understanding of what is being considered is linked to empirical observation (but not reducible to it—“facts” do not “speak for themselves”).

Empirical Research and Further Development of Marxist Business Cycle Theories

The basic approach presented by Weisskopf in his seminal papers has been followed, and significantly further developed, by the majority of Marxists who have subsequently done empirical/theoretical work on the profit rate.7 It has become the most common (though not universal) approach to Marxist empirical studies of the rate of profit. The largest and best known part of such work remains concerned with the secular behavior of the profit rate.8 Among the works in this tradition investigating the U.S. economy9 are Duménil, Glick and Rangel (1984, 1987); Michl (1988); Wolff (2001, 2003); Duménil and Lévy (2002a, 2002b, 2004a, 2011); Brenner (2002); Harvey (2005); and Glyn (2006). A very few studies used this framework for its other purpose of considering the behavior of capitalist business cycles themselves, including Hahnel and Sherman (1982); Henley (1987); a series of works by Goldstein in the late 1990s (1996, 1999, 2002); Bakir (2006, 2015); Bakir and Campbell (2006); and Cámara Izquierdo (2013).

Two issues are always key in determining the nature of empirical results that one gets when investigating theoretical issues: what particular combinations of categories of real-world data one uses to represent the theoretical categories involved, and what particular data sets one uses for the categories of real-world data that one has chosen to use. The many variations on these issues in the works of the researchers just referred to generally leave most results qualitatively the same, and hence support similar theoretical conclusions. A few procedures adopted by small minorities of empirical researchers yield qualitatively different results, and from those some qualitatively different theoretical conclusions. Given both the intention of this article and its space limitation, we will present our own empirical results as “broadly representative” of the majority of the empirical work on U.S. business cycles, and use it to indicate theoretical conclusions that can be made about the nature of U.S. business cycles. The technical details of our specific treatment are presented in Bakir (2015). We end this section by discussing some of the treatments of concepts that yield qualitatively different results from the “generalized majority” position.

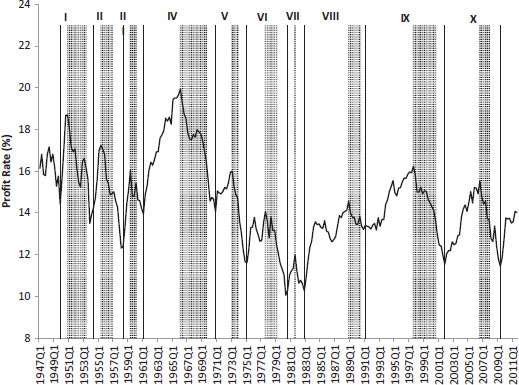

The quality of U.S. government economic data involved in computing a national private rate of profit10 dramatically improved after WWII, and hence all the work referred to above considers a time frame from then until the time of the study. Considering a business cycle to be from trough to trough, the first postwar cycle started in 1949. When Weisskopf published his work he was able to study five cycles up to 1975. Using quarterly data, figure 1 summarizes profit rate behaviors of the U.S. economy through the beginning of the 11th cycle that we are in presently. The vertically striated background sections indicate the B phases in each cycle (explained below), with the recessions as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Business Cycle Dating Committee being the periods following them to the end of the cycle.

Figure 1 immediately presents visually the most important broad result of Marxist empirical studies of business cycles (the dark vertical lines separate the cycles), strong support for the Marxist understanding of them as profit rate driven. Almost without exception,11 each cycle consists of three phases. In the first phase called A, the profit rate is rising and output is expanding. The rising profit rate serves as both “push” and “pull” for increased investment that increases growth, as explained in the introduction. In phase B (indicated by background light vertical lines) the profit rate stops rising and starts to fall (which will be discussed further below) while output continues to grow. The extended nature of the process of reducing investment because of the fall in the rate of profit and the lag of the effects of reduced investment on growth together yield the continued though slowing growth in this phase. Eventually the effects of the falling rate of profit cause growth to first stop and then reverse, initiating phase C characterized by a continued fall in the rate of profit and an output contraction (recession). A phase A of a new cycle is initiated when the fall in the rate of profit and its effects on the economy have proceeded far enough to create the conditions for the rate of profit to once again begin to rise.

The empirical support for the Marxist explanation of the business cycle output downturn in phase C of each cycle as caused by the preceding fall in the rate of profit in phase B immediately posed the question: what causes the rate of profit to begin to fall in phase B of each cycle? As discussed in the introduction, three explanations for a falling rate of profit (be it a secular fall, or our concern in this article, the business cycle downturns) were dominant in the Marxist discourse in the 1970s. Weisskopf’s empirical work found that for the five pre-neoliberal business cycles which he could study, a rise in the organic composition of capital proxied by the potential output/capital ratio (Y*/K) contributed very little to the phase B profit rate downturn, the realization failure proxied by the capacity utilization (Y/Y*) contributed only moderately, and a wage squeeze (which he referred to as the rising strength of labor, unfortunately, as indicated above) proxied by the wage share (W/Y) was by far the major contribution.

Since a “stylized fact” of neoliberalism is that labor lost power to capital (everywhere, but particularly in the U.S.), would one expect that a wage squeeze could no longer cause business cycle downturns after the full onset of neoliberalism? In fact the dominance of the rise of the wage share (W/Y) as the cause of the business cycle downturns remained true going into the neoliberal period, but what caused this continued dominance changed economically in a fundamental way in accord with the new neoliberal economy.

Bakir and Campbell (2006) and Bakir (2015) evince in a detailed empirical presentation the important continuity and the important change in the operation of the business cycle in the U.S. under neoliberalism. What remained the same as in the earlier post-WWII period was that of the three factors discussed above, the phase B fall in the rate of profit that leads to the later cyclical downturn in output was dominated by the fall in the profit share (P/Y), or equivalently (as indicated above), by the rise in the wage share (W/Y).

To understand the change in the business cycle dynamics, it is necessary to separate the price indices from the real quantitates.

where W, Y, ω, and L are as defined above, pw and py are the wage and output price indices, y is the real output, and w is the average hourly real wage.

Weisskopf had already noted that both the ability of workers to gain significantly greater real wage gains than real productivity gains and the price effects contributed to phase B profit downturns. What he did not stress was that the real effects were consistently more important than the price effects, notwithstanding that the latter were not negligible. And of course what he could not have noted then was that exactly this was to reverse under neoliberalism, with price effects becoming more important than real effects. Hence under neoliberalism, despite the cyclical downturn continuing to come from an increased wage share, this now involved a very different economic content in that it no longer represented important real wage gains for workers. This change is consistent with the general stylized fact of a weakened labor movement under neoliberalism.

Table 1 indicates how the phase B increase in the real wage to productivity ratio w/(y/L) dominated the price effect pw/py for cycles I-V during the post-WWII compromise period, and how that was subsequently reversed. The well-known attack on real-wage growth that began in the early 1970s is already apparent in Table 1, but the domination of the real effects over the price effects continued in the first of the two 1970s transitional cycles, cycle V, because of the collapse in productivity and the continued slow growth of the price effects. By cycle VI at the end of the 1970s the continued restrained real wage growth and the staunched real productivity decline combined with the significantly increased price effects to give equal contributions from the price and real effects. After that price effects came to be more important than real effects in the subsequent three periods of fully consolidated neoliberalism, cycles VIII, IX and X.

Table 1 Growth Rates of Wage Share and Its Component Variables in Phase B of Each Cycle (%)

We will end this section by discussing three conceptual issues involved in calculations of the rate of profit that cause minor to major changes in the empirical results.

i

Pre-tax vs post-tax profits. There is an important economic issue connected to this difference: what rate of profit are we interested in? That must depend on what question we are interested in answering. For example, if we are interested in determining what part of total output is captured by capital and what goes to workers, then because the state is part of capital’s infrastructure for the operation of capitalism we would use pre-tax profits. If instead we are interested in what incentives and resources private capital have to throw capital back into the circuits of accumulation, then we would consider the post-tax profits.

Empirically these differ. For a graphical presentation of the persistent difference, see Basu and Vasudevan (2013, Figure 1). To a first approximation these look like the same graph simply offset by a constant. A more careful examination reveals a slight narrowing of the gap over the whole period due to the well-known reduction in corporate tax rates. This narrowing is presented more clearly in a graph by Bakir (2015, Figure 5) where the axes for the two graphs are shifted so the graphs roughly coincide from the mid-1980s onward, thus displaying a gap before that due to the higher corporate tax rates. As most work with the rate of profit concerns how it changes over time, the relatively constant gap means that for most purposes one will get the same qualitative economic results using either series. To the extent that most work with the profit rate is concerned with private capital’s behavior and accumulation, after-tax profits are used somewhat more often.

ii

Including interest payments in profits vs excluding them. Nonfinancial businesses treat net interest payments as operating expenses, and so the after-tax profits given in the BEA’s NIPA tables are the sum of dividend payments plus retained earnings. We and a number of other authors argue that the net interest payments are analogous to dividend payments and should be treated as a distribution of profits (to the capital they took loans from as opposed to the capital that owns the enterprise). Bakir and Campbell (2010, 336, 340) detail this treatment, including an indication of data sources for all these components and a graph of the relative contributions of these three components of profits over the years.

Empirically including or excluding interest payments makes much less difference in the level of profits than the issue of before vs after taxes. (See again Basu and Vasudevan, 2013, Figure 1). From WWII until the late 1960s the two series were practically identical. They then diverged some in the 1970s and 1980s due first to the high interest rates and subsequently to the increased indebtedness of nonfinancial corporate business. The gap was then narrowed with the reduction of interest rates in the 1990s and their further extreme reduction in the 2000s, and with non-financial corporate business reversing its debt problem by 2000 to become a net creditor (Bakir and Campbell, 2010, 332), though the gap was not entirely eliminated as it had been prior to the 1970s.

iii

Historical cost vs replacement cost of capital. Economically, we and the large majority (but not all) of Marxists doing empirical research on the profit rate now and over the last four decades (for example, all the ones mentioned in the introduction) would argue it does not make sense to use the historical cost of capital data. The capitalist decision-makers whose choices determine the dynamics of capital and from that (and the class struggle) the rate of profit make their choices based on the replacement cost of capital, so that is the relevant variable for considerations of the dynamics of the profit rate. Empirically using the historical cost gives a “falling rate of profit bias” (a clockwise rotation) in the presence of inflation of capital prices, which is significant for strong inflation and negligible for minimal inflation. For a detailed discussion of all the technical issues involved in this difference and their effects on the resulting profit rates, see Basu (2013).

Conclusion

Marxist theories’ attention to the profit rate as centrally important for understanding the dynamics of capitalism is empirically supported as also being centrally explanatory for capitalist business cycles. Empirical work since the late 1970s has determined that it is the wage share (a “wage squeeze”) more than the organic composition of capital (accumulation of capital relative to labor) or the capacity utilization (realization) that causes the cyclical downturns in the rate of profit that in turn cause the business cycles. But even when the wage squeeze was predominantly the result of real wages rising faster than real productivity in the long post-1966 decline in the profit rate that led to the neoliberal restructuring, this cannot be simply blamed on “greedy workers” as argued by conservatives. The 1971 to 1975 and 1975 to 1981 cycles that cover most of the fall were characterized by sharp reductions in wage gains compared to the preceding period, and in the former case an actual decline. To the contrary, the cause of the “wage squeeze” was a sharp decline in the growth of real productivity relative to the preceding period, negative in both cycles and dramatically so in the first. While the rise in the wage share continued to be the dominant cause of the cyclical downturn during the neoliberal period, it came to represent very different economics. The shift in the relative price indices of output and wages came to be the more important factor as opposed to the earlier domination of the gains in the real wage to productivity ratio. That this change occurred reflects the increased role of financial mechanisms in neoliberalism, and above all the decreased relative power of the working class.

Notes

1 While the majority of Marxists would endorse this terse statement, we consider it valuable to consider the critique of it by the Marxist school of thought associated with the Association for Economic and Social Analysis (AESA). We consider it a fact that not every action of every firm is always motivated by profit maximizing and seeking to accumulate their profits, and the AESA correctly argues against such “profit rate reductionism” which has appeared in some Marxist literature. We do consider that “on average,” “over the long run,” and “aggregated over firms and time” the pursuit of profit and accumulation does emerge from the other important factors as central. Hence while we accept “overdetermination” and “decentering” in the sense of a necessary rejection of “profit rate reductionism,” we do not agree with the extension of that to what we consider to be a general position of this school of thought, that all factors need to be treated symmetrically, none prioritized for understanding the general behavior of capitalism. Resnick and Wolff (1987) comprehensively lays out the broad theoretical basis for this AESA position, Cullenberg (1994) applies it directly to the issue of the (falling) rate of profit, and Norton (1994) presents the arguments for this position in a particularly well-written and accessible short article. This disagreement on the degree of importance of the profit rate to capitalism’s performance is largely irrelevant for the focused topic of this paper, where we show empirically that without exception the downturn in business cycles since WWII involves first a downturn in profits and soon thereafter a downturn in output, and then discuss what factors are most important in those business cycle profit rate downturns.

2 This followed from the fact that early Marxists, including Marx, while they were careful to theoretically stress that a quantitative time frame for a crisis of capitalism linked to its transcendence could not be specified, all believed such a crisis was coming “soon” and hence focused their attention on understanding what such a crisis would involve.

3 The exact chronology of when each suggested explanation first appeared in the Marxists discussions is not important for this article and will not be addressed here for reasons of space. For works on Marxist crisis theories including disproportionality, which later disappeared as a generalized crisis theory, see Shaikh (1978), Perelman (1987) and Clarke (1994). On the emergence of these three strands as central by the 1970s, see among others Weisskopf (1979), Reuten (2002) and Bakir (2006). Of concern here is only that at the end of the 1970s when the approach to business cycle research described here arose, all three of the positions were supported by significant numbers of Marxists and as a result were then the object of an important ongoing debate.

4 Reading these papers underlines the intimate interconnection of the beginning of modern Marxist business cycle research and the existing crisis theories.

5 In a sense overproduction and underconsumption denote the same problem looked at from opposing sides; there is not enough demand to buy all the goods produced if production is at capacity. This is also often referred to in Marxist literature as a realization problem. However, they often carry slightly different connotations. Overproduction tends to focus on the growth of capital and from that productive capacity (why potential supply is greater than demand), while underconsumption tends to focus on things that reduce demand and hence why demand falls short of potential supply.

6 If we write P/K = Y/K – W/K, we can state this more carefully to say that if increases in wages cause any increase in output, the profit rate still falls as long as (which is almost always the case) the increase in Y/K is less than the increase in W/K. This “wage squeeze” is also often expressed in both mainstream and Marxist literature in terms of the growth of the hourly wage rate (ω) and labor productivity (Y/L) (or the corresponding real terms to be discussed below), where L is the total labor hours: the profit share P/Y = 1 – W/Y = 1 – ωL/Y = 1 – ω/(Y/L), so the profit share (and hence the profit rate as long as wage-induced changes in Y/Y* and Y*/K from the new wages are secondary) falls if the growth of the hourly wage rate is more than the growth of labor productivity. This adds a note of caution to calling something like the fall in the rate of profit at the end of the 1960s and early 1970s a “wage squeeze” with its implication of “greedy workers.” This fall could as well result from a fall in the growth of labor productivity as from an increase in the growth of hourly wages. There was in fact a strong such fall at that time. This fall in the growth of labor productivity itself could result from either changed relations of production or simply a slowed increase from technological advances in capital.

7 Two fundamentally different Marxist approaches to business cycles and crises involving empirical work are much less broadly used and for reasons of space can only be indicated and not discussed here. Although Sherman (1991; Sherman and Kolk 1996) specifically presents his model as Marxist, numerous other commentators have argued it is actually essentially Keynesian. (e.g., Glombowski [1982]). Anwar Shaikh has argued for decades that capitalists determine the dynamics of the system on the basis of marginal profit rates as opposed to the profit rate, and has just released a comprehensive statement of his approach and his related empirical work (Shaikh 2016).

8 Cycles are sometimes considered in this literature in order to study the changes in the secular trend over time. Our purpose in discussing cycles is to investigate the cyclic behavior itself, as an aid to understanding the dynamics of capitalism.

9 Very similar procedures applied to other developed or underdeveloped countries generally yield qualitatively very different results. This is an area of comparative research that has hardly been started, determining if the differing results come from the differently defined operational variables (often due to different national accounting procedures) or if these truly represent significantly different business cycle dynamics for different capitalist countries, and if so what that means theoretically about the nature of world capitalism.

10 Weisskopf and many of the works in that tradition cited used the nonfinancial corporate sector as a proxy for the private capital sector, because the data was most complete for that sector and because it constituted roughly 70% of the total. Some of the later works cited above extended that to include the non-financial non-corporate sector. The data for the financial sector presents particular problems, and as far as we are aware there are only three works on this in this tradition in the literature; Duménil and Lévy (2004b), Bakir and Campbell (2013) and Bakir (2015).

11 Cycle VII was exceptionally short due to economic policies that caused the rate of profit to return to falling before the expansion would have led to its fall without those policies, and as a result the economy went right from phase A to phase C in that business cycle.

References

Bakir, E. 2006. “The Post-World War II Nonfinancial Corporate Business Rate of Profit in the United States: Cycles, Trends, and the Effects of Financialization.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Utah.

Bakir, E. 2015. “Capital Accumulation, Profitability, and Crisis: Neoliberalism in the United States.” Review of Radical Political Economy 47(3): 389–411.

Bakir, E. and A. Campbell. 2006. “The Effect of Neoliberalism on the Fall in the Rate of Profit in Business Cycles.” Review of Radical Political Economics 38(3): 365–373.

Bakir, E. 2010. “Neoliberalism, the Rate of Profit and the Rate of Accumulation.” Science & Society 74(3): 323–342.

Bakir, E. 2013. “The Financial Rate of Profit: What Is It, and How Has It Behaved in the United States?” Review of Radical Political Economy 45(3): 295–304.

Basu, D. 2013. “Replacement versus Historical Cost Profit Rates: What Is the Difference? Does It Matter?” Metroeconomica 64(2): 293–318.

Basu, D. and R. Vasudevan. 2013. “Technology, Distribution and the Rate of Profit in the US Economy: Understanding the Current Crisis.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 37(1): 57–89.

Brenner, R. 2002. The Boom and the Bubble. London: Verso.

Cámara Izquierdo, S. 2013. “The Cyclical Decline of the Profit Rate as the Cause of the Crisis in the United States (1947–2011).” Review of Radical Political Economics 45(4): 463–471.

Clarke, S. 1994. Marx’s Theory of Crisis. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Cullenberg, S. 1994. The Falling Rate of Profit. London: Pluto.

Duménil, G, M. Glick, and J. Rangel. 1984. “The Tendency of the Rate of Profit to Fall in the United States.” Contemporary Marxism 9: 148–164.

Duménil, G, M. 1987. “The Rate of Profit in the United States.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 11(4): 331–359.

Duménil, G. and D. Lévy. 2002a. “The Field of Capital Mobility and the Gravitation of Profit Rates (USA 1948–2000).” Review of Radical Political Economics 34(4): 417–436.

Duménil, G. 2002b. “The Profit Rate: Where and How Much Did It Fall? Did It Recover? (USA 1948-2000).” Review of Radical Political Economics 34(4): 437–461.

Duménil, G. 2004a. Capital Resurgent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Duménil, G. 2004b. “The Real and Financial Components of Profitability (United States, 1952–2000).” Review of Radical Political Economics 36(1): 82–110.

Duménil, G. 2011. The Crisis of Neoliberalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Glombowski, J. 1982. “A Comment on Sherman’s Marxist Cycle Model.” Review of Radical Political Economy 14(1): 42–49.

Glyn, A. 2006. Capitalism Unleashed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goldstein, J. 1996. “The Empirical Relevance of the Cyclical Profit Squeeze: A Reassertion.” Review of Radical Political Economics 28(4): 55–92.

Goldstein, J. 1999. “The Simple Analytics and Empirics of the Cyclical Profit Squeeze and Cyclical Underconsumption Theories: Clearing the Air.” Review of Radical Political Economics 31(2): 74–88.

Goldstein, J. 2002. “The Profit Squeeze Is Supported by the PW Cycle Indicator.” Review of Radical Political Economics 34(1): 75–77.

Hahnel, R. and H. Sherman. 1982. “The Rate of Profit over the Business Cycle.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 6: 185–194.

Harvey, D. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Henley, A. 1987. “Labour’s Shares and Profitability Crisis in the U.S.: Recent Experiences and Post-war Trends.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 11: 315–330.

Michl, T. 1988. “The Two-Stage Decline in U.S. Nonfinancial Corporate Profitability, 1948–1986.” Review of Radical Political Economics 20(4): 1–22.

Norton, B. 1994. “Moses and the Prophets! Radical Economics and the Search for a Foundation.” Review of Radical Political Economics 26(3): 111–118.

Perelman, M. 1987. Marx’s Crises Theory: Scarcity, Labor, and Finance. New York: Praeger.

Resnick, S. A. and R. D. Wolff. 1987. Knowledge and Class: A Marxian Critique of Political Economy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Reuten, G. 2002. “Business Cycles: Marxian Approach.” In Encyclopedia of Macroeconomics, B. Snowdon and H. Vane, eds., 73–80. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Shaikh, A. 1978. “An Introduction to the History of Crisis Theories.” In U.S. Capitalism in Crisis, Union for Radical Political Economics, ed., 219–241. New York: Economics Education Project of the Union for Radical Political Economics.

Shaikh, A. 2016. Capitalism: Real Competition, Turbulent Dynamics, and Global Crises. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sherman, H. 1991. The Business Cycle. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sherman, H. and D. Kolk. 1996. Business Cycles and Forecasting. New York: Harper Collins College Publishers.

Union for Radical Political Economics (URPE), ed. 1978. U.S. Capitalism in Crisis. New York: Economics Education Project of the Union for Radical Political Economics.

Weisskopf, T. 1978. “Marxist Perspectives on Cyclical Crises.” In U.S. Capitalism in Crisis, Union for Radical Political Economics, ed., 241–260. New York: Economics Education Project of the Union for Radical Political Economics.

Weisskopf, T. 1979. “Marxian Crisis Theory and the Rate of Profit in the Postwar U.S. Economy.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 3(4): 341–378.

Wolff, E. 2001. “The Recent Rise of Profits in the United States.” Radical Review of Political Economics 33: 315–324.

Wolff, E. 2003. “What’s Behind the Rise in Profitability in the US in the 1980s and 1990s?” Cambridge Journal of Economics 27(4): 479–499.