People care which company they work for

Meet Lisa. She works in the field of corporate communications and marketing, and has done so for more than twenty years. We spoke to her the other day about her recent experiences at work, in the same way that we speak to hundreds of people every year about their experiences at work. Lisa told us that she’d recently moved from one company to another and then back again, and we wanted to understand more. Here’s what she said.

Marcus and Ashley: Why did you leave Company A* after eighteen years?

Lisa: I’d moved from a role focused on events—the big events we put on for our customers and partners—to a role focused more on marketing. I found I couldn’t be creative in the marketing role, and then my prior events role had been filled and I had nowhere to go. So the only way I could get back into events was to go elsewhere.

Us: That’s what led you to look at Company B?

Lisa: Yes. And anyway, after all this time at Company A, I felt like exploring something new, and a new environment.

Us: As you considered working for Company B, what was most important to you about the company?

Lisa: The brand—whether it was seen to be a name-brand company in a market-leading position; innovation and the pace of innovation; whether I could build something new; where the job was located and whether I could work remotely; how cool the place was; whether I would learn there; and whether I could try new things easily. Those were some of the things I remember thinking about.

Us: And how did you try to evaluate each of those?

Lisa: Obviously, through the interviews I did for the job. But I’d also done my research beforehand—I spent six months researching the company and the job, on Google, on Glassdoor. I spent two months prepping for my interviews, and at the same time I talked to as many people there as I could find.

Us: What did you conclude at the end of this?

Lisa: I thought Company B probably wasn’t a perfect place, but it had checked enough of my boxes for me to feel comfortable going there.

Us: So you went to Company B. How long did you stay there for?

Lisa: Two years.

Us: Given you’d spent eighteen years at Company A, were you expecting to be at Company B longer than two years?

Lisa: Yes, for sure.

Us: So can you explain why you were only there for two years, given how thorough you’d been in your research about the job? What happened?

Lisa: What happened is that I met my manager. I mean, I’d met her during the interview process, obviously, and there were a few things that bothered me—but when I started I saw her true colors, and that’s when things started to go wrong.

Us: What bothered you during the interview process?

Lisa: Her style struck me as severe, and formal, and a bit hierarchical. But I figured that was just her game face—how she was to the outside world—and that if I joined her team it would be different. But it wasn’t.

Us: And when did you realize that?

Lisa: It was on Day Thirteen.

Us: Day Thirteen? How can you be so precise?

Lisa: I wrote it down in my calendar. I wrote down all the key dates during my time at Company B—it was my way of documenting what was a really tough experience for me. On Day Thirteen I was in a meeting with my manager and a more senior executive, and the senior person asked what I thought was a simple question about booking hotel rooms, and I answered, and my manager looked shocked. As soon as the meeting finished, she took me to one side and said, “We don’t share that sort of thing with senior people here. Next time run it by me.” And from that point on she micromanaged me, and I realized that she was fear-based, both in how she thought of her bosses and in terms of how she ran her team.

Us: Were there any other days you noted in your calendar?

Lisa: On Day Fifteen I wrote down, “Possible last day at Company B” for my two-year anniversary, and “Last day at Company B” for my four-year anniversary.

Us: Crikey. Just to confirm—you spent months researching a company; you did seven interviews, in each of which you had carefully prepared questions to help you understand whether this would work for you; and two weeks in you’d not only decided to leave but given yourself a timeline. Is that right?

Lisa: Yes, that’s it. I knew fifteen days in that I wasn’t there long term.

Us: And the main reason for that was your manager, and her style?

Lisa: Yes. And it wasn’t just my manager—other leaders seemed to operate based on fear, too.

Us: When you were at Company B, were you introduced to their Core Values or Leadership Principles or anything like that?

Lisa: Yes! I was handed a laminated page of them at my orientation. I was thrilled!

Us: Why was that?

Lisa: I read them and thought, “These are great!” There was one I remember in particular—it was about disagreeing and then committing, about having the courage to speak up if you disagreed with what was being said, but then committing wholeheartedly to the ultimate decision when it was made. I thought that was really exciting, and would make for a great environment. But then I started work, and I realized—darn, these just aren’t true. Worse than that, some people here use them for evil.

Us: For evil?

Lisa: Yes, they justify bad behavior by pointing to the Leadership Principles. So if they want to silence dissent, they tell people it’s time to commit to the direction they want to go. Which is the opposite of what that idea is meant to be about.

Us: Ah, OK. So pretty quickly you decided to find a path back to Company A, right?

Lisa: Yes.

Us: And in the light of this experience with Company B, what was important to you as you looked for this next role?

Lisa: Three things—culture, leadership, and the work I’d be doing.

Us: What do you mean by culture?

Lisa: It’s the tenets of how we behave. I think of it like a family creed—this is how we operate and treat one another in this family.

Us: What are some words you’d use to describe Company A’s culture?

Lisa: Let me see. Inclusive, collaborative, kind, generous, trusting, fair, supportive. And I think the senior leaders are good people who lead ethically.

Us: Were those things uniform across Company A, in your experience?

Lisa: I think I was fortunate—they showed up in the teams I worked on for sure. But I know people who were less fortunate, who didn’t see these things.

Us: How do you explain that?

Lisa: For me, it’s a question of whether each team leader believes in the culture of the company—whether they get the culture or not. If they do, you’re fortunate. If not, you’re not.

• • •

From the outside looking in, it’s pretty hard to figure out what it might be like to work for a particular company. If you’re job hunting, you might start by searching online as Lisa did—perhaps on Glassdoor or one of the other job boards where employees can rate their current company—or by talking to friends about where they’ve worked and what their experiences were. You might try to talk to a recruiter, although it’s tricky to do that if you’re not yet sure you’re going to apply. You might try to figure it out by reading the coverage of a company in the press, but this can be frustrating, since articles tend to focus more on a company’s products or its strategy, rather than on its culture per se. Wherever you look, you’ll find yourself wondering if what you’re discovering is really representative of the company, and is giving you a good sense of the inside story. In search of more objectivity and breadth, then, you might turn to Fortune magazine’s annual ranking of the 100 Best Companies to Work For.

Fortune publishes its ranking every January, and this issue of the magazine is one of the most widely read of the year. The ranking is based on an anonymous survey of the employees at each company (known as the “Trust Index”), together with a submission that each company puts together describing how it invests in its people and what it has to offer them (called the “Culture Audit”). From all this, the editors at the magazine and the analysts at the Great Place to Work Institute (which conducts the research) put together a list that tells you which companies are the best to work for that year, together with descriptions of the various perks they offer and brief testimony from current employees. In 2018 the top six, in order, were Salesforce, Wegmans, Ultimate Software, Boston Consulting Group, Edward Jones, and Kimpton Hotels, selected for reasons ranging from the pragmatic (paying bonuses for employee referrals, offering Starbucks gift cards during busy times, on-site child day care) to the noble (giving millions of dollars’ worth of reclaimed food to the hungry, building environmentally friendly offices, always trying to promote from within) to the quirky (Salesforce has an entire floor dedicated to ohana, the Hawaiian for family, while Kimpton offers all new hires a welcome care package complete with each person’s favorite snacks).

If you are indeed looking for a job, you read Fortune’s list in search of insights about a given company. What will your colleagues be like? How will they treat you? What will a typical day be like? Will your work be interesting, challenging, and valued? Is this a company that really cares for its people? If you go through the long process of applying, and interviewing, and negotiating an offer, and ultimately landing a job there, will this be a company that puts as much into you and your career as you’re going to put into it?

What, precisely, is this list measuring about these companies? Read the submissions, the press releases, and Fortune’s own descriptions of the winners, and the word you land on is culture. Salesforce has a “family culture,” hence the Ohana floor. Wegmans has a culture based on its mission to “help people live healthier, better lives through food.” Kimpton Hotels has an “inclusiveness culture.” Each of these companies, it appears, has figured out what kind of culture it wants to build, and then has made it onto the list because it has been resolute and effective in its pursuit. Judging by these and other examples, this thing called culture really matters. It is potentially more important than what the company does—“Culture eats strategy for breakfast!”—how the company does it, how much the employees get paid, or even the company’s current stock price.

Culture matters, according to the voluminous literature on the topic, because it has three powerful contributions to make. First, it tells you who you are at work. If you’re at Patagonia, you’d rather be surfing. You work in beautiful Oxnard, California, and your onboarding consists of a day-long beach party where you are gifted the CEO’s autobiography—Let My People Go Surfing—and where your first meeting takes place around a campfire. If you’re at Goldman Sachs, then never mind the surfing—you’d rather be winning. You wear your bespoke suit every day because you’re a winner. It means something to say that you work for Deloitte, or for Apple, or for Chick-fil-A—and this meaning says something about you, something that locates you and differentiates you, that defines your tribe.

Second, culture has come to be how we choose to explain success. When Tesla’s stock was on the rise in the early part of 2017, it wasn’t because people were finally getting the electric cars they’d paid deposits for a year earlier—they weren’t. Rather, it was because Elon Musk had created a culture of cool, a place where you couldn’t even see the cutting edge because it was so far behind you. When Toyota had to recall over six million vehicles, the direct cause was a problem with the shift-lever assembly, but the deeper explanation we arrived at was that it was a problem with their polite yet win-at-all-costs culture.

And third, culture is now a watchword for where we want our company to go: almost overnight, a big part of the job description of senior corporate leaders has become to create a specific sort of culture, a culture of “performance,” perhaps, or a culture of “feedback,” or a culture of “inclusion,” or a culture of “innovation”; to shape the direction of the company they lead by infusing it with particular traits that govern how people behave. Beyond explaining the now, culture has become our handle on the next.1

As a team leader you are going to be told, repeatedly, that you must take stock of all this because you are responsible for embodying your company’s culture, and for building a team that adheres to these cultural norms. You will be asked to select only applicants who fit the culture, to identify high-potentials by whether or not they embody the company culture, to run your meetings in a way that fits the culture, and, at company off-sites, to don the T-shirts and sing the songs.

All of which is fine, right up to the point where you start to wonder what, precisely, you are being held accountable for. Read the Fortune list again and you’ll be struck by the fact that a very small percentage of what’s written about your company is in your job description. Having an on-site day-care facility, giving all employees 20 percent of their time to pursue their own interests, offering large rewards for referring a new hire, and building solar panels on the roof are all admirable initiatives, yet none of them is within your control. They are commitments made by others—the executive committee or the board—and while you may think them worthy, and may indeed be proud that they are something your tribe contributes to the world, you can’t do anything about them. They are off in some other place, far from the day-to-day projects and deadlines, the ongoing actions and interactions, that actually comprise your world of work.

When people ask you what it’s “really like” to work at your company, you immediately know you’re going to tell them not about the solar panels and the cafeteria, but about what it’s really like. So you’ll get real, and talk about how work is parceled out, whether many managers play favorites, how disputes get resolved, whether the real meeting happens only after the formal meeting is over, how people get promoted, how territorial the teams are, how large the power distance is between senior leaders and everyone else, whether good news or bad news travels fastest, how much recognition there is, and whether performance or politics is most prized. You’ll get down to the two-foot level of how work actually gets done, and try to tease out what your company truly feels like to the people on the ground.

You won’t know whether to call this “culture” or not, just as you won’t necessarily know how to label each of these two-foot-level details, but in every fiber of your being you’ll know that this ground-level stuff is what’ll decide how hard people will work once they’ve joined, and how long they’ll stay. This ground-level stuff is what they truly care about. Indeed, this ground-level stuff is what you truly care about.

In which case, your most pressing question, as a team leader, will be something like this: If I am to help my team give their best, for as long as possible, which of these details are most critical? Tell me the most important ones, and I’ll do my level best to pay attention to those.

We’ve spent the last two decades attempting to answer this question for you. In the next few pages we’ll outline what we’ve found, and then we’ll focus the rest of this book on going deeper, and on giving you insights and prescriptions for how you can address the things that matter most.

And in so doing, the first lie we’ll need to expose is precisely that people care which company they work for. It sounds so odd to label this a lie, since each of us does indeed feel some sort of connection to our company, but read on, and we think you’ll see that while what each of us truly cares about may begin as “company,” it quickly morphs into something else rather different.

All quantitative research requires qualitative digging, which is why, a little while ago, we spent a few hours with a team of people in Cisco’s office in Krakow, Poland.* We were curious about their experience of work, and what their team was like. The team had about fifteen members overall, engaged in various jobs supporting Cisco’s customers. We asked the group about the things they did frequently—daily or weekly or monthly or quarterly—that were important to them. Three of the team members answered by talking about lunch. We always bring our lunches to work, they said, instead of going to the cafeteria. And there’s a spot on the patio outside where we eat together. We always eat at the same time as one another, no matter what is happening that day, and sometimes we talk about work, and other times about stuff outside work—this is what we do every day.

Later on, we saw where the fifteen-person team worked (our initial discussion had taken place in a conference room). They worked at a long row of workstations, each separated from its neighbors by vertical dividers. The three people who ate their packed lunches together pulled us to one side. Look! they said, pointing to an unremarkable spot on the floor, a few feet from the workstations. This is where we huddle! We asked what they meant. They said that when something happened during the day that they needed to talk about, they would leave their workstations and form an impromptu huddle where they could figure out what to do.

Here we have a team of fifteen people, doing real work in the real world, and within it a sub-team of three people, also doing real work in the real world. And the three take time every day to eat together, and also—maybe because of the lunches, or maybe not because of them, or maybe just because—have a way of quickly breaking the routine configuration of their workspace to solve problems together.

What is the “culture” of this three-person team-within-a-team? Is it different from the “culture” of the bigger, fifteen-person team, and if so, how? Who knows? All we do know is that both the three-person miniteam and the fifteen-person team are extremely productive and highly engaged. Back at Cisco’s headquarters in San Jose, California, the CEO, Chuck Robbins, is doing his best to build an enthusiastic, committed workforce, but he is thousands of miles and several organizational levels away from the day-to-day realities that these team members face, and he knows that there’s a limit to what he can control from the center. All he can hope to do is to encourage these local teams—and every other of his thousands upon thousands of teams—to build the sort of work experience that gets the best from each and every team member.

What, then, should he be asking them to focus on? What are, in fact, the most important aspects of our experience of work?

The only way to rigorously answer this question is as follows: First, create two groups of people, one group from teams with high performance (high productivity, high innovation, high customer satisfaction, low voluntary turnover, low lost work days, whatever performance means in a given company or business unit), the second group from teams with low or average performance.

Next, start asking questions about what these teams are like on the inside. Ask many, many questions of the high performers, and then ask the same questions of the low performers. Search for those few questions where the people on the high-performing teams say that they strongly agree and the people on the mid- to lower-performing teams do not. The goal here is to try to find what is distinctive about the high-performing teams through the eyes of the people on those teams.

Over the last several years we’ve repeated this research hundreds of times in many different companies, always zeroing in on the questions that most clearly sort the best from the rest. We are not the first to undertake this kind of research, of course. Back in the late 1990s the Gallup Organization did pioneering work on engagement, eventually identifying twelve conditions as the drivers of it, and since then organizations such as the Corporate Executive Board, Korn Ferry, and Kenexa have added to our growing body of knowledge and our understanding of engagement at work, and of how we can measure it most reliably and with the most validity. Our work built on this existing research, as all sound research should—research findings are provisional, after all—and, in the end, we wound up identifying just a few aspects of the employee experience that exist disproportionately on the highest-performing teams. These eight aspects, and these eight precisely worded items,* validly predict sustained team performance:

1. I am really enthusiastic about the mission of my company.

2. At work, I clearly understand what is expected of me.

3. In my team, I am surrounded by people who share my values.

4. I have the chance to use my strengths every day at work.

5. My teammates have my back.

6. I know I will be recognized for excellent work.

7. I have great confidence in my company’s future.

8. In my work, I am always challenged to grow.

You might notice a few things about these items right away. First, the team members are not directly rating their team leader or their company on anything—they are rating only their own feelings and experiences. This is because, as we’ll see in chapter 6, people are horribly unreliable raters of other people. When we ask someone to rate someone else on an abstract quality such as empathy or vision or strategic thinking, their responses tell us more about the person doing the rating than the person being rated. To get good data we have to ask people about their own experiences.

Second, you may also notice that the eight items fall into two broad groupings. The first is the odd-numbered items:

1. I am really enthusiastic about the mission of my company.

3. In my team, I am surrounded by people who share my values.

5. My teammates have my back.

7. I have great confidence in my company’s future.

These deal with the elements of a person’s experience created in their back-and-forth interactions with others on the team—the communal experience of work, if you will. What do we all share, as a team or as a company? We can think of these as the “Best of We” questions.

The second group comprises the even-numbered items:

2. At work, I clearly understand what is expected of me.

4. I have the chance to use my strengths every day at work.

6. I know I will be recognized for excellent work.

8. In my work, I am always challenged to grow.

These deal instead with the individual experience of work. What is unique about me? What is valuable about me? Do I feel challenged to grow? We can think of these as the “Best of Me” questions.

These two categories of experience—We experiences and Me experiences—are the things we need at work in order to thrive. They are specific; they are reliably measured; they are personal; they reveal a local individual experience intertwined with a local collective experience. They are everyday. And if we think about the team in Poland, while we might not know what its “culture” is, we do know that lunching together and huddling together will have some bearing on the team members’ feeling that their teammates have their backs, that they share a sense of what excellence is, that they are called on to do their best work frequently, that they catch each other doing things right, and so on. What we see in the eight questions is a simple way of measuring experience-at-work, and one that you, the team leader, can do something about.

And what more than two decades of research into teams and their leaders has to tell us is this: what distinguishes the best team leaders from the rest is their ability to meet these two categories of needs for the people on their teams. What we, as team members, want from you, our team leader, is firstly that you make us feel part of something bigger, that you show us how what we are doing together is important and meaningful; and secondly, that you make us feel that you can see us, and connect to us, and care about us, and challenge us, in a way that recognizes who we are as individuals. We ask you to give us this sense of universality—all of us together—and at the same time to recognize our own uniqueness; to magnify what we all share, and to lift up what is special about each of us. When you come to excel as a leader of a team it will be because you’ve successfully integrated these two quite distinct human needs.

Over the course of this book, we’ll explore precisely how the best leaders do this—what they pay attention to and how they interact with the people around them. At the same time, we’ll explore the eight items in more detail, and we’ll see how the lies we’re told at work push back, hard, against each of these eight critical aspects.

• • •

But what of our first lie, that people care which company they work for?

Well, we now know that these eight questions measure very precisely those aspects of our experience of work that matter the most—in other words, the aspects that drive performance, voluntary turnover, lost work days, accidents on the job, and customer satisfaction. So, if it is true that in large part people’s experience at work is driven by the company they work for, then when we ask these eight questions to every person in every team at a particular company, we should get, generally, the same responses. There shouldn’t be variation from team to team, because the day-to-day experience of working at this particular company should remain mostly consistent.*

But that’s not the case—in fact, it’s never the case. The statistical measure of variation is called range, and we’ve found that these scores always have a greater range within a company than between companies. Experience varies more within a company than between companies.

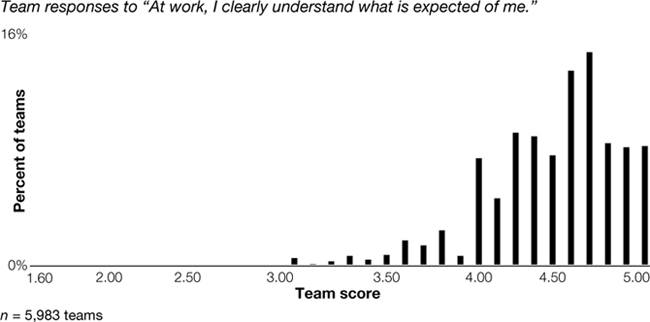

Here’s what this looks like. This is how 5,983 teams at Cisco answered the second question, “At work, I clearly understand what is expected of me.” (See figure 1-1.)

Now, this is a very basic question. If you’ve spent much time in business organizations, you’ll know that they devote a lot of energy to talking about strategies and plans and priorities and themes and critical initiatives and business imperatives, and Cisco is no different. Yet for all this effort, these nearly six thousand teams had a widely varying sense of what was expected of them. And we saw this variance across all teams at every company that we surveyed.

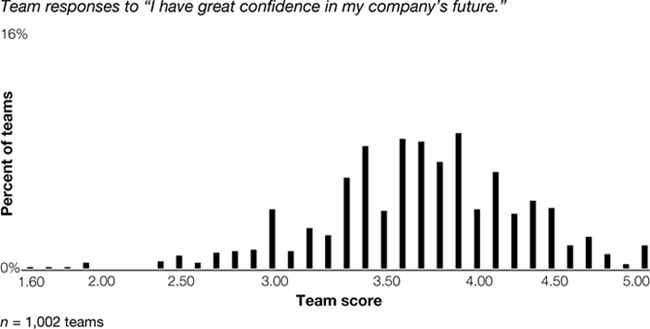

Here’s how 1,002 teams at Mission Health answered the seventh question, “I have great confidence in my company’s future.” (See figure 1-2.)

If there’s any item that should vary between companies rather than within them, it would surely be this one. After all, one company will presumably have only one future, and this future should seem the same regardless of which team you’re on. Yet it doesn’t feel like that. People’s responses to this question vary significantly depending on which team they’re on, within the same company: different team, different level of confidence in the future.

We see similar patterns on all eight of the questions—we see, in other words, that when we zero in on the critical aspects of our experience at work, they vary more team-to-team than they do company-to-company. Any ideas—like the idea of culture—that rest on the assumption that our experience of a company is uniform, no matter where we sit, don’t hold up. Any ideas—again, like the idea of culture—that rest on the assumption that our experience will vary company to company are incomplete, because our experience will vary more within a company than between companies. And any ideas—again, like the idea of culture—that rest on the assumption that this broad, unchanging company-ness is what defines our experience of work are simply wrong.

Instead local experiences—how we interact with our immediate colleagues, our lunching-on-the-patio companions, and our huddling-in-the-corner partners—are significantly more important than company ones. At least, that’s what all this research is telling us.

Moreover, if we care most which company we work for, it follows that there should be no connection between our experience on a given team and our choice to stay with a given company—because company trumps team. But whenever we run an analysis, we find that when a team’s score is low on these items, members of that team are significantly more likely to leave the company. At Cisco, for example, we’ve seen that when someone’s experience of their team moves from the top half, companywide, to the bottom half, their likelihood of leaving the company increases by 45 percent. When people choose not to work somewhere, the somewhere isn’t a company, it’s a team. If we put you in a good team at a bad company, you’ll tend to hang around, but if we put you in a bad team at a good company, you won’t be there for long. The team is the sun, the moon, and the stars of your experience at work. As Edmund Burke, the Anglo-Irish writer and philosopher put it as far back as 1790, “To love the little platoon we belong to in society is the first principle (the germ, as it were) of public affections.”2

When we push on the data, and examine closely its patterns and variations, we arrive at this conclusion: while people might care which company they join, they don’t care which company they work for. The truth is that, once there, people care which team they’re on.

• • •

Recently the ADP Research Institute conducted a nineteen-country study on the nature of engagement at work—what drives it, and what it drives. We’ve included a summary of the findings in the appendix, but here are three highlights that you’ll want to know. First, virtually all work is in fact teamwork. In companies with over 150 employees, 82 percent of people work on teams, and 72 percent work on more than one team. Even in small companies, of fewer than twenty people, this finding holds: 68 percent of those in small companies report working on a team, and 49 percent say they work on more than one team. This proved to be so in every single country in the study.

Second, we know that if you do happen to work on a team you are twice as likely to score high on the eight engagement items, and that this trend linking engagement to teams extends to multiple teams—in fact, the most engaged group of workers across the working world are those who work on five distinct teams.

Third, just like Lisa, those team members who said they trusted their team leader were twelve times more likely to be fully engaged at work.

The good news in all this for you, the team leader, is that what people care most about at work is within your control. You might not be able to weigh in on your company’s parental-leave policy, or the quality of its cafeteria, but you can build a healthy team—you can set clear expectations for your people, or not; you can position each person to play to his or her strengths every day, or not; you can praise the team for excellent work, or not; you can help people grow their careers, or not. And you can, over time, build trust with your people, or not. Of course, given the “always-on” nature of your daily work, attending to each of these is challenging, but at least they are indeed part of your daily work.

The bad news for you is that your company, most likely, looks past this, so while you’re doing your best to create these experiences for your people, your company may not be holding your fellow team leaders accountable for doing the same on their teams. Companies almost universally miss the importance of teams, as evidenced by the fact that most companies don’t even know how many teams they have at any moment in time, and who is on them, let alone which are the best ones—we are functionally blind to teams. And our overemphasis on culture leads companies to remove responsibility from where it resides—with the team leaders—and instead to focus on generalities. You now know that your company does not have a uniform culture, that if there is something distinct about your company’s culture then it is unmeasurable, that the total score of your company’s employee survey is simply the clumping together of lots of highly varied team-level surveys, and that these clumps mask what really matters. You now know that when a CEO sets out to build a great company, all she can do—and it’s a lot—is strive to build more and more teams like her company’s best teams.

And you now know that often what’s written about company cultures are stories masquerading as data—stories of one world, and then another, and then another, vivid, intriguing, charming, and occasionally a bit scary, but not real. Like Narnia, or like Middle-earth, if hobbits had jobs.

• • •

If the most important experience of work is the experience of team, what should we make of all the “culture of . . .” things with which we began? Are they all entirely irrelevant?

In his fascinating book Sapiens,3 and again and in more depth in its sequel, Homo Deus,4 the historian Yuval Noah Harari asks what it is that explains the success of humankind over all other species. Having examined and rejected the usual explanations—we’re not alone, as a species, in using tools, or in having language, or in making plans, or in experiencing consciousness—he moves on to explore our notions of reality. Objective reality, as we know, is a reality that exists independently of our attitudes or feelings about it: if you stop believing in gravity, you’ll still fall to the ground if you jump out of the window. Subjective reality, on the other hand, is defined precisely by your attitudes and feelings: if you have a toothache yet your dentist tells you she can’t find anything the matter (there is no objective problem), your tooth still hurts.

But Harari goes on to argue that there is a third kind of reality, that this kind of reality is unique to humans, and that this kind of reality explains the dominance (for good or ill) of our species. There are some things that are real simply because we all agree they’re real—things whose existence depends not on any objective reality, nor on any individual’s subjective reality, but rather on our collective belief in them. By this logic, money, for example, exists only because all of us agree it does. Initially this might sound odd—surely money is just money, not some sort of mass belief system—but here’s the rub: when we all cease to believe in these realities, they cease to be real. If you and everyone else stop believing, all of a sudden, that a particular piece of paper is worth $10, then it actually and rather immediately ceases to be worth $10. This is more or less what happened in India on the evening of November 8, 2016, when the government announced that the very next day certain bills would no longer be legal tender, and those bills turned instantly from Things That Are Valuable Because We All Agree They Are to Things That Are Valueless Because Some Of Us Don’t.

Harari calls these extended, communal realities intersubjective realities, and tells us that they’re the reason our achievements as a species are so different from those of our planet-mates. They enable us to coordinate our actions with those of people we may never meet, across distance and across time. Our belief in the intersubjective reality of nation, for example, enables us to cooperate with our fellow citizens to finance and build monuments, or to wage war; our belief in the intersubjective reality of democracy allows us to elect governments and to follow their laws. Our intersubjective realities are the distinguishing feature—the apex technology—of Homo sapiens.

What are our intersubjective realities in the world of work? One, obviously, is the idea of the company. We can’t touch it; it exists only in the realm of laws (another intersubjective reality), and when we stop agreeing it exists, it ceases to exist. Obviously, the stock-market value of a public company is another example. As is that company’s brand and brand value. And its bank balance. All of these are useful—essential, even—to our ability to organize lots of people to achieve complex and enduring goals. Without them, and the many other intersubjective realities in the world of work, we would have none of the things that “companies” have produced since we invented them. But that doesn’t make them real, in the sense that gravity is real, or in the sense that a toothache is real. Or in the sense that the other people at work—your team—are real.

And just as the idea of the company is, in this particular sense, unreal, so is the idea of company “culture.” It’s a useful fiction. That doesn’t mean we should dispense with it; it does mean, however, that we should be careful not to mistake it for something it isn’t. Culture locates us in the world. It consists of stories we share with one another to breathe life into the empty vessel of “company.” But—and here’s the kicker—so powerful is our need for story, our need for communal sense making of the world, that we imagine that our company and its culture can explain our experience of work. And yet it can’t. So strong is our identification with our tribe that it’s hard for us to imagine that other people inside our company are having a completely different experience of “tribe” from ours. Yet they are—and these local team experiences have far more bearing on whether we stay in the tribe or leave it than do our tribal stories.

• • •

How can you make sense, then, of the things that are clearly different from one company to the next, things to which you’re accustomed to attaching such importance? Patagonia does have a drastically different type of onboarding than Salesforce. Goldman Sachs does have a very different dress code from Apple. What are these things, and how are they different from the real-world experience of work?

The difference is this: these things are signifiers, designed to lure you in. You may not care which company you work for, but since you do care about which company you join, these signifiers are crafted to help a company attract a certain kind of person by highlighting what the company thinks this kind of person values. This is why these signifiers show up time and again in promotional materials, and why they are so prominent in various company rankings—because companies want it that way. These kinds of perks are plumage—peacock feathers for people. They sound cool because they’re designed to get your attention, just like plumage is. So when you read about how a certain company gives each employee “twenty-percent” time to focus on personal projects or claims to always promote from within, just remember that these beautiful feathers are designed almost exclusively to attract you, and that this attraction, as most attractions tend to, will fade.

The biggest difference, of course, between cultural plumage and the real world is that the impact of plumage on how you and your team do your work every day is slight. That’s not what it’s for. It is a shared fiction, and it exists to attract a certain kind of person to join the company. And as with all shared fictions, the moment you all stop collectively believing in the plumage, it vanishes. Team experience, on the other hand (how you talk to one another and work with one another), has large and lasting impact on how you do your work, and it doesn’t require all of you to agree to believe in it. It is what it is. And whether or not you all believe in it or can all describe it in the same way, it will nonetheless influence both how effectively your team works and for how long, and how many of your teammates will choose to stay.

• • •

When you study excellence and what leads to it—what creates it—there is a dog that doesn’t bark.* Actually, a couple of them. Company doesn’t bark. And cultural plumage doesn’t bark. Instead, sitting there in plain sight is what was in plain sight in Poland. What the three people there shared, as a key part of their experience of work, was not about a place to eat, but rather—critically—about the people to eat with. While they might think of Cisco as a place that affords them a table to sit at or a corner of the office to huddle in, if we give them those things yet take away their teammates, or change the sorts of interactions they have with those teammates, their experience vanishes. In a very real sense the spot they huddle on with a couple of teammates matters more to them than all the perks Cisco well-intendedly throws their way. What’s in plain sight, when we study excellence at work, is the groups of people doing actual work together—what’s in plain sight is teams.

This is why teams matter, and it’s why they matter much more than cultural plumage matters.

Teams simplify: they help us see where to focus and what to do. Culture doesn’t do this, funnily enough, because it’s too abstract.

Teams make work real: they ground us in the day-to-day, both in terms of the content of our work and the colleagues with whom we do it. Culture doesn’t.

And teams, paradoxically, make homes for individuals. Whereas culture’s focus leans toward conformity to a common core of behaviors, teams focus on the opposite. Teams aren’t about sameness—they aren’t, at their best, about marching in lockstep. Instead they’re about unlocking what is unique about each of us, in the service of something shared. A team, at its finest, insists on the unique contribution of each of its members, and is the best way we humans have ever come up with of harnessing those distinctive contributions together in the service of something that none of us could do alone.

In the last few years, there has been a lot of talking and writing about teams in corporate circles. Sadly, much of it has yet to grasp the main point. The general direction of the discussion so far has been that we should pay attention to teams because there are a lot of them at work. This is, of course, true—although one could make the case that this isn’t news. Granted, given new communications and information technologies, teams can now be assembled spanning more geographies and time zones and organizational units than ever before, but the fact that there are now more teams and more different sorts of teams than ever before isn’t the big thing. The big thing is that only on a team can we express our individuality at work and put it to highest use.

In a sense, that’s what the rest of this book is about. To see it clearly, we have to let go of our ideas about cultural plumage, because only when we do so does the fact of team emerge—quietly, simply, powerfully—from its shadow. And as we do this we come to realize what is perhaps the biggest problem of all with the idea of culture: it doesn’t actually help us understand what to do more of, less of, or differently. Whether culture is a real thing or not, whether it defines our tribe at work or not, whether it’s a marker of what sort of company we’re joining or not, it won’t tell you, the team leader, what to do to make things better. For that, we must take you to where the experience lives: to your team, and networks of teams, and their leaders. That’s what matters most.

• • •

There are three things for you to do as a leader of a team. First, you should know the answers to the eight questions for your team, all the time. There are technologies available to help you do this, but the easiest place to start is to ask your team members, one person at a time. Whatever their answers are, you’ll always be smarter because of them, and you’ll always know you’re paying attention to something that matters.

Second, read on to understand more clearly how to build a great team, and how the lies you’ll encounter get in the way of that. Your role as team leader is the most important role in any company. And who your company chooses to make team leader is the most important decision it ever makes. You have by far the greatest influence on the distinctive local experience of your team. This is a weighty responsibility, but at least it’s yours. We want to help you step into it.

And third, when you’re next looking to join a company, don’t bother asking if it has a great culture—no one can tell you that in any real way.

Instead, ask what it does to build great teams.

*Obviously, we’ve disguised the names of the companies.

*One of the great joys of writing as a team of two is that it allows us to bring both of our perspectives and, critically, experiences and stories to the task, resulting in what we hope is a richer book. This presents, however, one small challenge when writing about an experience that one but not both of us had, and it’s the challenge of which pronouns to use. Joint authors before us have taken various approaches to this, either by referring to themselves in the third person (“When Marcus interviewed such-and-such . . .”) or by beginning every story with some sort of parenthetical clarification (“When one of us [Ashley] was in Poland . . .”), neither of which we feel makes up in clarity what it takes away in readability. So we’ve decided that whether an event described here was experienced by one of us alone or by both of us, we’ll just say “we.” We hope you will forgive us a little pronoun flexibility in the service of easier reading.

*Strictly speaking, an item is a statement that a survey-taker responds to. As items are statements, not questions, they don’t come with question marks. However, they are often referred to as questions, to ensure maximum confusion for those of us trying to figure out what’s going on.

The eight engagement items discussed in this book are copyright ADP.

*More precisely, we would see only as much variation within teams as we would within the company as a whole.

*GREGORY: “Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?”

HOLMES: “To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.”

GREGORY: “The dog did nothing in the night-time.”

HOLMES: “That was the curious incident.”

—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, “The Adventure of Silver Blaze,” in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (London: George Newnes, 1894).