CHAPTER 6

KNOWN BY GOD IN THE OLD TESTAMENT

In our day, personal identity has become a sort of “do-it-yourself project.” As sociologist Anthony Elliot observes, “the anything-goes thinking that was fostered by postmodernism has drilled all the way down into the fabric of our identities.”1 Finding, defining, or even designing yourself is almost a moral imperative. And personal autonomy is valued above all other considerations.2 However, as David Jopling contends, the truth is that “persons come to know themselves in being known by persons other than themselves.”3

A regular feature in my weekend newspaper is “The Two of Us,” which looks at the friendship of two individuals. It’s a typical human-interest story that focuses on how two people relate and what they mean to each other. Spouses, parents and children, friends, coworkers, and siblings are the standard fare. One article that stood out for me recently concerned the relationship between two sisters. When talking about her sister Lisa, Bea commented: “Lisa sees the best in me. . . . There’s something reassuring and beautiful about someone really knowing you.”4 It is true to say that we often feel “ourselves” when we are around those who know us best.

This has certainly been my experience. In January 2000 I returned to live in Australia having spent sixteen years living overseas. Reentry, let’s say, was a bit bumpy. I had less than two weeks to find somewhere to live, set up home, and settle three children into schools before starting a new job teaching high school, for which I had no formal training. As well as these challenges, my sense of self had taken a battering. My personal identity gauge was pointing towards empty and the light was flashing. Slowly getting on top of things and making new friends kept the motor running, but refueling came from renewed contact with those who knew me best.

Two old friends, Frank and Martin, were especially helpful. I had known them most of my life, and we had kept in contact while I was overseas for the previous sixteen years. Martin likes to tell the story of asking me to dice an onion on our first bushwalk as teenagers. Not knowing that you had to peel it first left a lasting impression it seems. Frank was a flatmate in my early twenties and happily recalls my early attempts at cooking, which included serving up a relatively raw chili con carne. Back living in Sydney after so many years, Frank called me every Sunday night, and I went on regular overnight bushwalks with Martin. If I was having trouble remembering who I was, being known by Frank and Martin was a great reminder. There is indeed something reassuring and beautiful about someone really knowing you.

“The self is a network of relationships forged by significant experiences (past and present), actions, and connections with people, places, things and events. The self therefore becomes ‘a bundle of relationships.’ ”

Michael Allen Fox5

“The ‘self’—understood as an autonomous individual—does not exist.”

Michael Horton6

“Just as it is impossible for a man to confront himself and to see himself from all sides or for a person who is still developing to know of himself whose child he is, just so certainly does man fundamentally need the meeting with another, who investigates and explains him. But where is the other to whom the being man could put the question: who am I?”

Hans Walter Wolff7

It was also at this point that I found being known by God to be of great assistance. If knowing God had given my life purpose from my youth, being known by God proved to be a great comfort in a time of confusion and difficulty. In this chapter and the next, we begin looking at how being known by God gives us a secure identity and is also a reassuring and beautiful thing.

What does the Old Testament teach about being known by God? To answer this question, four matters call for attention:

1. The fact that God knows us better than we know ourselves;

2. What it means to be known by God;

3. The kindred ideas of God knowing your name and being remembered by God; and

4. Two key Old Testament texts that expound and apply the theme of being known by God in striking ways.

At a few points I will include some material from the New Testament that relates to an Old Testament topic of interest. However, most of what the New Testament teaches about being known by God, and being known by Christ, will be postponed until the next chapter.8

GOD KNOWS US INTIMATELY AND PERSONALLY

The most famous passage in the Bible about being known by God is Psalm 139. It opens with the words, “You have searched me, LORD, and you know me.” The psalmist claims that God is familiar with all his ways (v. 3b). Whether sitting or standing, rising or lying down, speaking or silent, God’s knowledge of him is greater even than his knowledge of himself (vv. 2–6).

The psalmist gives two explanations for such wonderful knowledge (v. 6). The first is the fact that God is always present with him (vv. 7–12): “Where can I go from your Spirit? Where can I flee from your presence?” (v. 7). And the second is that God’s knowledge of the psalmist originates from and completes a divine knowing begun before he was born (vv. 13–18): “For you created my inmost being; you knit me together in my mother’s womb” (v. 13). As artists know their work, so the psalmist infers that God our Creator knows what he has made.

“God is closer to me than I am myself.”

Meister Eckhart9

“God knows me better than I know myself. . . . God knows the true me; the person I really am.”

William J. Mander10

“How beautiful it is that God knows us better than we know ourselves or anyone else can.”

Hawani Tola11

There are in fact two sorts of knowledge spoken of in Psalm 139: factual knowledge, the idea that God knows all about me; and relational knowledge, the fact that God knows me personally. In the psalm the two are closely related. God knows about me because he knows me. Some languages mark these two types of knowledge with different words. German, for example, uses wissen and kennen to refer to knowing something and knowing someone respectively. The Hebrew, Greek, and English languages use the same verbs “to know” for both.

God’s knowledge of everything and everyone is in fact taught in all of Scripture. God knows our ways, days, thoughts, secrets of our heart, and so on. First John 3:20 affirms God’s omniscience bluntly: “he knows everything.” “God knows,” a phrase repeated three times in Paul’s letters, testifies to this conviction. In 2 Corinthians 11:11 Paul uses it to convince his readers that he loves them: “God knows I do!” Even more telling is 2 Corinthians 12:2–3, where Paul affirms that “God knows” something that Paul himself does not know: namely, whether during some mystical experience the apostle was in or out of his body.

But to say that God knows us does not simply mean that God knows about us. If, to use the language of 2 Corinthians 5:11 ESV, God’s omniscience means that “what we are is known to God,” God’s relational knowledge means that who we are is known to God. According to the Bible, although God knows all about everyone, he does not know everyone in the intimate sense of personal relationship. Psalm 138:6 can speak of God knowing the proud “from afar” (ESV), but the righteous up close (he “regards” them). Similarly, according to Matthew and Luke Jesus will say to some at the last judgment, “I never knew you” (Matt 7:23; 25:12; Luke 13:27). If God’s omniscience is an attribute of God that speaks of his transcendence and overlaps with his omnipresence,12 his knowing us concerns his immanence and is related to his love.

Knowing things is the principal way of knowing in our day. Justin Thacker notes that

in the dominant modern view of knowledge today, derived from the Enlightenment, knowledge is seen as objective and detached from the knower. It is possible to “know” something without being in any way engaged or committed to it. The model here is scientific knowing.13

However, in contrast to the modern West, relational knowledge is the main framework for knowledge in the Bible. The expression “to know” in the biblical sense originates in “Adam knew Eve” (Gen 4:1 ESV; cf. Judg 21:12), a reference to sexual relations, which testifies to the fact that in the Bible to know something can mean to experience it. This knowing by experience can also be seen in descriptions of people “knowing” the loss of children (Isa 47:8), disease (Isa 53:3), and divine punishment (Jer 16:21). Knowing these things is not about having an adequate intellectual grasp of them, akin to our sense of scientific knowledge, but being “acquainted with them existentially, emotionally, socially and cognitively.”14 It is this sort of knowledge with which we are concerned when thinking about being known by God. God knows us intimately and personally. In fact, he knows us better than we know ourselves.

WHAT IT MEANS TO BE KNOWN BY GOD

As with every relationship, our relationship with God has two sides: believers know God and are also known by him. Whereas knowing God is the focus of countless academic and popular books and articles, being known by God has received much less attention.15 In one sense this is understandable, given that the Bible speaks of God knowing us much less often that it does of us knowing God. However, to measure the importance of being known by God by counting references would be a mistake. Although not numerous, texts which speak of being known by God punctuate the canon, turning up from Genesis to 2 Timothy and appearing in every major genre. And these texts refer both to individuals and to the nation Israel and the church.

References to being known by God appear at critical points in the biblical narrative. In the Old Testament, those who are known by God include key figures in God’s unfolding plan to save the world:

• In Genesis 18 the explanation that God has chosen Abraham to become God’s channel of blessing to the nations (v. 18) is that God knows him (v. 19): “For I have known him, in order that he may command his children and his household after him, that they keep the way of the LORD, to do righteousness and justice, that the LORD may bring to Abraham what He has spoken to him” (NKJV).

• In Exodus 33 Moses is described as God’s friend, with whom he speaks face to face (v. 11), and he had told Moses, “I know you by name and you have found favor with me” (v. 12).

• In 2 Samuel 7, following the giving of the Davidic covenant, David praises God saying, “there is no one like you, and there is no God but you” (v. 22) and confessing to God about himself that “you know your servant, Sovereign LORD” (v. 20).

• In Jeremiah 1, Jeremiah opens his prophecy with the word of the Lord that establishes his calling: “Before I formed you in the womb I knew you, before you were born I set you apart; I appointed you as a prophet to the nations” (v. 5).

• Finally, in Amos 3 the nation of Israel itself is said to be known by God: “You only have I known of all the families of the earth” (v. 2 NRSV).

“What matters supremely is not, in the last analysis, the fact that I know God, but the larger fact which underlies it—the fact that he knows me. I am never out of his mind. All my knowledge of him depends on his sustained initiative in knowing me. I know him because he first knew me, and continues to know me. He knows me as a friend, one who loves me; and there is not a moment when his eye is off me, or his attention distracted from me, and no moment, therefore, when his care falters.”

J. I. Packer16

As we will see in chapter seven, being known by God is just as significant in the New Testament.

God took the initiative to know Abraham. He knows Moses by name. He knows his servant David. He knew Jeremiah from before he was born. He knows Israel as opposed to other nations. To be known by God is to be known intimately and personally by him. But more can be said. The references to being known by God in the Old Testament support linking our understanding of the concept to three related ideas: (1) belonging to God; (2) being loved and chosen by God; and (3) being a child of God.

Belonging to God

In the most general sense, to be known by God signals God’s ownership of an individual or group. It means that we belong to God. In Numbers 16, the story of the rebellion of Korah and his followers, Moses explains that God will separate the innocent from the guilty before bringing his judgment:

Then he said to Korah and all his followers: “In the morning the LORD will show who belongs to him and who is holy, and he will have that person come near him. The man he chooses he will cause to come near him.” (v. 5)

However, the Greek translation of the Old Testament (LXX) renders the verse slightly differently, as “God knows those who belong to him.” And in the New Testament, Paul in 2 Timothy 2:19 prefers the LXX of Numbers 16:5, quoting almost word for word: “The Lord knows those who are his.”17

In the LXX translation of Numbers 16, being known by God and belonging to God amount to much the same thing. In defining what it means to be known by God, Walther Eichrodt drew the same conclusion: “God knows his people . . . that is to say, he has introduced them into a permanent relationship of mutual belonging.”18 Adolf Schlatter also concluded that to be known by God is to be “the property of God.”19

Along with belonging to our families, cultures, friendship groups, and nations, being known by God introduces a new belonging. It is one that is critical to our identity, is not subject to change, and affects everything about us, including our purpose, character, and destiny. We will have more to say about this in part three, “Reflecting on Relevance.”

Chosen by God

The link between being known by God and being chosen by God is introduced in the first explicit reference to God’s relational knowledge in the Bible. In Genesis 18, in connection with the fulfillment of the Abrahamic promise, God explains his grand plans for the patriarch: “Abraham will surely become a great and powerful nation, and all nations of the earth will be blessed through him” (v. 18). Then he concludes with the words, “for I have known him” (v. 19 NKJV). That God’s choice of Abraham is in view is clear from other numerous references in Genesis pertaining to election and the covenant. In Genesis 12:1–3, for instance, God’s promise to Abraham is to make him into a great nation, to bless him, to make his name great, and so on, in distinction from blessing someone else. And God’s selection of a particular line of seed turns out to be the backbone of the plot of Genesis 12–50, where the narrative concentrates on Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph in succession. Thus it is understandable that English versions, such as the NIV and NRSV, translate Genesis 18:19, “For I have chosen him,” even though the original Hebrew is yadah, the standard verb “to know” in the Old Testament.

Amos 3:2 is another text that connects being known by God with divine election. There, in the context of reminding Israel of God saving them from slavery in Egypt, the Lord remarks: “You only have I known of all the families of the earth” (ESV). Once again several English translations of the Bible interpret the sense in terms of God’s choice of the nation. The NIV, for example, has: “You only have I chosen of all the families of the earth.” The NLT does well to capture the close nature of the bond that being known by God suggests in this verse: “From among all the families on the earth, I have been intimate with you alone.”

F. F. Bruce observes, “There is no difference between being known by God and being chosen by him.”20 Being known and chosen by God also has an impact on our personal identity. As with Abraham and the nation Israel, God chooses us for a purpose. We are chosen for a vocation, task, and mission. Our election is to be part of something much bigger than ourselves, and puts our otherwise fleeting lives in a different light. More will be said on this in chapter ten, “Shared Memory and Defining Destiny.”

Child of God

Both belonging to God and being chosen by God give some content and context to the theme of being known by God. To be known by God is to be singled out as God’s special people, those destined for blessing (see Abraham in Gen 18) and not for judgment (see the account of Korah’s rebellion in Num 16). Obviously, in these cases being known by God has some considerable advantages!

But is being known by God simply another way of referring to those whom God chooses for blessing? Belonging to God can be a rather general and ambiguous notion. In what realm does the ownership pertain? In what sense do we belong to him? A third more specific definition that overlaps with and sharpens the first two calls for attention. If Eichrodt and Schlatter define being known by God in terms of belonging to him, and Bruce locates its meaning in divine election, John Calvin proposed that “to be known by God simply means to be counted among His sons.”21 Compared to the first two definitions, understanding being known by God as a parent knows their child deepens our grasp of the concept.

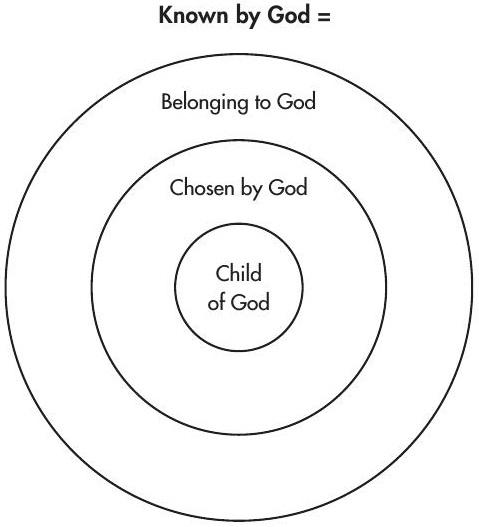

However, it is not the case that being known by God in the Bible refers to three different things. The three definitions are best conceived as more specific versions of the same reality. To belong to God is to be chosen by him. And we belong to God not just as his people, but more specifically as his children. The relationship of the three definitions can be illustrated as concentric circles:

The identity of being a child of God is a long and sturdy theme in the Bible and deserving of its own chapter (see chapter nine). We have already seen that Adam and Eve, before being ejected from the garden for their transgression, were known by God as his children by virtue of being made in the image of God (see chapter five). It is also the case that the theme of divine adoption in the Old Testament is connected with being known by God.

This theme of being the children of God in the Old Testament is connected to two great moments in salvation history.22 The first is when God adopts Israel as his son at the time of the exodus. In explaining that Egypt’s firstborn sons will be killed in judgment God says to Moses: “Say to Pharaoh, ‘This is what the LORD says: Israel is my firstborn son, and I told you, “Let my son go, so he may worship me.” But you refused to let him go; so I will kill your firstborn son’ ” (Exod 4:22–23). The prophet Hosea makes the same connection between the exodus and sonship for Israel: “When Israel was a child, I loved him, and out of Egypt I called my son” (Hos 11:1). In the New Testament, Paul reflects a similar understanding when he describes the nation of Israel’s blessings as including their “adoption to sonship” (Rom 9:4).

Two references to being known by God in the Old Testament appear in contexts that specifically mention the salvific event of the exodus. When Amos 3:2 refers to God’s election of Israel, “you only have I known” (ESV), it is preceded immediately by the reminder that Israel is the people God “brought up out of Egypt” (3:1b). Additionally, Hosea 13:4–5 sets God’s knowing the nation in the context of the same saving event: “I am the LORD your God from the land of Egypt; you know no God but me. . . . It was I who knew you in the wilderness” (ESV).

The second note of adoption in the Old Testament concerns God adopting the king of Israel as his son in the Davidic covenant. In 2 Samuel 7:14, God says of the Davidic king: “I will be his father, and he will be my son.” The promise is repeated with reference to Solomon in 1 Chronicles 28:6 when God addresses David concerning the question of who will build the temple: “ ‘Solomon your son is the one who will build my house and my courts, for I have chosen him to be my son, and I will be his father.” And in Psalm 2:7, a coronation psalm, the Lord says to his anointed king: “You are my son; today I have become your father.”

Once again, becoming a child of God in the Old Testament is linked to being known by God. The Davidic covenant in 2 Samuel 7 supports the nexus of being adopted by God and being known by God. Following David’s offer to build God’s “house” (in the sense of temple) being trumped by God’s promise to build David’s “house” (in the sense of dynasty), God promises to adopt David’s offspring who will succeed him on the throne (v. 14). Amidst the children of God, who are the nation of Israel, the Davidic king will be the son of God par excellence (see also Ps 2:7). As we have already noted in chapter two, in the wake of this overwhelming news and the resulting feelings of inadequacy, David asks: “Who am I, Sovereign LORD, and what is my family, that you have brought me this far?” (2 Sam 7:18b). His answer to his own question underscores that he was known by God: “For you know your servant, Sovereign LORD” (7:20a).

A Secure Attachment to God

How does being known by God as his child connect to our theme of personal identity? Developmental psychology and psychiatry have some insights to offer.

Loyola McLean explains that when it comes to personal identity, “the self forms within and through relationships and in particular attachment relationships.”23 “Attachment theory” helps explain the key role that parents play in giving their children a stable sense of self:

In attachment theory our early attachment relationships foster the development of our representations of self and other. Modern theory and much research now demonstrate that it is secure attachment relationships or an internalized secure attachment state of mind that give rise to a positive sense of self.24

Children develop a secure and positive sense of self when their parents form a secure attachment to them: “Early security fosters a stable self and a coherent narrative about oneself. A relatively coherent and stable personal identity underpinned by a strong and secure sense of self is now being shown to be critical to psychological health and well-being.”25 Significantly for our purposes, a critical factor in a secure attachment between a parent and a child is being known by the parent. McLean explains:

Involved, loving parents know their children intimately. Indeed, a child’s well-being appears to initially depend less on knowing his or her parents than on being known by them. . . . Attachment bonds are vital in both directions, but the caregiver is critical.26

In short, parents give their children their identity by knowing them. Children are named by their parents and receive their earliest experiences from them. Parents come to know their child’s personality, likes and dislikes, physical capabilities, needs and desires. They pass on their own tastes, values, and worldview to their children. Indeed, parents play a big part in the formation and maintenance of their children’s identity, especially when they are young.

“Similar to the human parent-child relationship, an attachment to God, where it is founded in a lived experience of being known and loved, can lead to a healthy sense of significance and is an effective source of comfort in response to dispiriting difficulties. Being known by God, who is holy and gracious, also offers moral direction, as the child of God seeks to take on the family likeness, and may offer the mental benefits that foster forgiveness and self-reflection that are associated with a secure state of mind.”

Loyola McLean and Brian Rosner27

At my stage of life, the death of a parent is increasingly a regular occurrence among my peers. I recall a conversation with one friend who had lost both of his parents within a couple of months. He reflected that without his parents around, he was beginning to wonder who he was. At best, parents are those who know us well and hold a more complete memory of our lives than anyone else. They establish the settings for our lives and reflect back to us our identity even when we are adults.

The idea of receiving your identity as a relational gift from your parents is suggestive for how being known by God as his child contributes to the believer’s personal identity. God gives us our identity as his children by knowing us intimately and personally.

KINDRED IDEAS

The Old Testament develops this theme of being known by God not only through explicit references to people being known by him, but also by reminders that God knows our names and is attentive to our lives.

Naming as Knowing

Names in every culture are critical to personal identity. Usually the answer to the question of who you are begins with your name. For this reason, “Who named you?” and “Why?” are regular conversation topics among new acquaintances. Surnames associate you with your family. And saying that someone “knows your name” is another way of saying someone “knows you.” Being on first-name terms with someone is an important matter in some cultures and may require some formality like a drink to mark the occasion. Nicknames and pet names indicate the closeness of a relationship. Middle names are often known only to a close circle of family and friends. As it turns out, names have an even greater significance in the Old Testament than in Western culture today.

“The Jewish idea of ‘naming’ implies more than just nomenclature; it involves the notions of determining the character and exercising authority over what is named (see Gen. 2:19; Ps. 147:4; Eccles. 6:10).”

John Muddiman28

Consistently, throughout the Bible God knows his people by name and they know his name. Isaiah 43 contains a message of comfort in which God calling his people by name is equivalent to belonging to God as his children and is set in the context of his work in creating and redeeming them:

But now, this is what the LORD says . . .

“Do not fear, for I have redeemed you;

I have summoned you by name; you are mine. . . .

Bring my sons from afar

and my daughters from the ends of the earth—

everyone who is called by my name,

whom I created for my glory,

whom I formed and made.” (Isa 43:1, 6b–7)

Similarly, in the New Testament when Jesus compares himself to a shepherd, he makes the point that “he calls his own sheep by name” (John 10:3). However, not only does God know his people by name, he sometimes changes their name as a sign of his thorough involvement in their lives and as an indication of his plans for them. Examples include God changing Abram’s name to Abraham, Sarai to Sarah, Jacob to Israel, and in the New Testament, Jesus changing Simon’s name to Cephas (Peter).

Even more intriguing is a group of three passages in Isaiah where God gives names to his people, but we are not told what they are. In Isaiah 56 God makes promises to the obedient eunuchs:

To the eunuchs who keep my Sabbaths,

who choose what pleases me

and hold fast to my covenant—

to them I will give within my temple and its walls

a memorial and a name

better than sons and daughters;

I will give them an everlasting name

that will endure forever. (Isa 56:4–5)

In an oracle of salvation in Isaiah 62, God promises his people a new name:

For Zion’s sake I will not keep silent,

for Jerusalem’s sake I will not remain quiet,

till her vindication shines out like the dawn,

her salvation like a blazing torch.

The nations will see your vindication,

and all kings your glory;

you will be called by a new name

that the mouth of the LORD will bestow. (Isa 62:1–2)

Third, in Isaiah 65 God will give his chosen servants another name:

Therefore this is what the Sovereign LORD says:

“My servants will eat,

but you will go hungry;

my servants will drink,

but you will go thirsty;

my servants will rejoice,

but you will be put to shame.

My servants will sing

out of the joy of their hearts,

but you will cry out

from anguish of heart

and wail in brokenness of spirit.

You will leave your name

for my chosen ones to use in their curses;

the Sovereign LORD will put you to death,

but to his servants he will give another name.” (Isa 65:13–15)

The context of all three passages concerns God’s determined intention to bless his people beyond their expectations. For this reason, the giving of a new name is reason to “sing out of the joy of their hearts” (Isa 65:14). The intensely personal nature of the giving of the name is underscored (“a new name that the mouth of the LORD will bestow,” Isa 62:2) along with its eternal significance (“I will give them an everlasting name” as a memorial within the temple, Isa 56:5). Significantly, in these verses our identity is not only known by God, but known only to God and then to us when he tells us.

Despite naming their children on their birth certificates, many parents give their young children “another name,” a nickname known only to family members and the closest of friends. Such monikers are generally not used in public. They function as signs of tenderness, intimacy, and affection.

The name of the main character in the popular children’s classic Winnie the Pooh by A. A. Milne is actually “Edward Bear.” He mostly goes by his nickname in the books, “Pooh Bear.” However, Tigger calls him “Buddy Bear,” and Christopher Robin, “Silly Old Bear.”

In the New Testament, we find a similar passage about God giving his people a new name. In Revelation 2:17 two words of encouragement are offered to the members of the church of Pergamum who are suffering persecution. One is “hidden manna”; the other is a reference to “a white stone with a new name written on it, known only to the one who receives it.” The consensus among biblical commentators is that “we simply do not know what the white stone signified, though clearly it did convey some assurance of blessing.”29 Whatever else the “new name” reference denotes, its hidden nature, known only to God and its bearer, speaks of intimate interpersonal relationship, a knowledge that encourages the one who overcomes to persevere. Being given a secret name by God is another way of affirming that someone is known personally by God as children are known by their parents.

The theme of naming as knowing is also often reinforced in the Bible’s narratives, where the characters who are named are the faithful to whom God is unwaveringly committed. In Exodus 1 the pharaoh is not named—he is just “the king of Egypt.” But Shiphrah and Puah, the lowly Hebrew midwives, are named (Exod 1:15). Similarly, in Ruth 4 Boaz is named, but the guardian-redeemer who refuses to buy the land from Naomi for fear of endangering his own estate is not.

In the New Testament, Timothy Keller points to something comparable in the parable of the rich man and Lazarus in Luke 16:

The rich man, unlike Lazarus, is never given a personal name. He is only called “a Rich Man,” strongly hinting that since he had built his identity on his wealth rather than on God, once he lost his wealth he lost any sense of self.30

If your life is characterized by faith in and obedience to the Lord, like Shiphrah, Puah, Boaz, and Lazarus, then God knows you by name, and your identity is secure in him. Your name is written in the Lamb’s book of life, a book written “from the creation of the world” (Rev 17:8).31

God’s Books

Along with knowing his people by name and even giving them new names, God keeps a list of our names. In both testaments of the Bible is mentioned an “eternal ledger”32 of those who belong to him, most often termed “the book of life.” The existence of such a book ties in with the Bible’s consistent interest in genealogies, family lists, and national registers in Israel. In biblical thought, names matter, especially the names of people who are known by God.

An early reference concerns God’s wrath in response to the idolatry of the golden calf in Exodus 32:31–33:

So Moses went back to the LORD and said, “Oh, what a great sin these people have committed! They have made themselves gods of gold. But now, please forgive their sin—but if not, then blot me out of the book you have written.” The LORD replied to Moses, “Whoever has sinned against me I will blot out of my book.”

The book that God has written seems to contain the names of those whose sins God has forgiven. The rest of the references in the Bible to this book are remarkably consistent on this point.

References in Daniel 12 and Psalm 69 reinforce the idea that those whose names are in the book are destined for salvation and those whose names are not will face judgment:

At that time Michael, the great prince who protects your people, will arise. There will be a time of distress such as has not happened from the beginning of nations until then. But at that time your people—everyone whose name is found written in the book—will be delivered. (Dan 12:1)

Charge them with crime upon crime;

do not let them share in your salvation.

May they be blotted out of the book of life

and not be listed with the righteous. (Ps 69:27–28)

The New Testament understands the book of life along similar lines. Those whose names are recorded in the book of life are told to rejoice (Luke 10:20), and “the church of the firstborn” are described as those “whose names are written in heaven” (Heb 12:23), along with Paul’s coworkers (Phil 4:3). In Revelation, having your name in the book of life is decisive for whether you are saved or not:

The Bible has an almost obsessive fascination with names. The first book of the Old Testament contains several genealogies (e.g., Gen 5:1–31; 10:1–32; 11:10–26; 22:20–24; 25:1–4, 12–18; 46:8–27). The first book of the New Testament opens with a list of the names of Jesus’s ancestors (Matt 1:1–17; cf. Luke 3:23–38). Censuses play a significant role at different points in biblical history (cf. Exod 38:26; Num 26; 2 Chr 2:17–18; Ezra 2). There are multiple lists of the sons and tribes of Israel (e.g., Gen 46:8–27; Exod 1:1–5; Josh 21:1–8; 1 Chr 2:1–2; 12:24–38; Ezek 48:1–35; Rev 7:1–8). Lists of the disciples of Jesus are also prominent (Matt 10:2–4; Mark 3:16–19; Luke 6:13–16; Acts 1:13). In all, some 2,600 proper names appear in the Bible’s sixty-six books.

And I saw the dead, great and small, standing before the throne, and books were opened. Another book was opened, which is the book of life. The dead were judged according to what they had done as recorded in the books. The sea gave up the dead that were in it, and death and Hades gave up the dead that were in them, and each person was judged according to what they had done. Then death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. The lake of fire is the second death. Anyone whose name was not found written in the book of life was thrown into the lake of fire. (Rev 20:12–15; cf. 3:5; 17:8; 21:27)

What is referred to simply as the “books” (Rev 20:12) are presumably the records of the lives of those whose names are not found written in the book of life, which form the basis of their judgment and condemnation. By contrast, Revelation 13:8 describes the book of life as “the Lamb’s book of life, the Lamb who was slain from the creation of the world” as a reminder that the basis of salvation is the cross of Jesus Christ. The book of life being decisive for our acquittal at the last judgment underscores the grace and mercy of God toward those whose names are therein written. Our names matter to God. And the fact that our names are in God’s book of life gives our otherwise fleeting lives a reassuring permanence.

Remembered by God

The relationship between being “known” by God and being “remembered” by God is evident in the report of the plight of the people of God in Egypt in Exodus 2:23–25:

During that long period, the king of Egypt died. The Israelites groaned in their slavery and cried out, and their cry for help because of their slavery went up to God. God heard their groaning and he remembered his covenant with Abraham, with Isaac and with Jacob. So God looked on the Israelites and he was concerned about [lit., knew] them.33

When God remembers, he is not simply bringing back to mind something he has forgotten. The Hebrew verb zakar is used in this way but never with God as the subject. Instead, God remembers in the sense that he acts on what he has called to mind. Lindsay Wilson explains the relationship between God remembering his covenant and God knowing us:

Being remembered by God presupposes God knowing you, but moves on beyond that. It results in God actively treating you according to his promises and purposes, and in light of his past commitments.34

God remembering those he knows is grounded in the fact that he made us. As Psalm 103:14 asserts: “he knows how we are formed, he remembers that we are dust.” But more often in the Old Testament, God knowing and remembering us has its basis in his redeeming us. God remembers his covenant on numerous occasions and makes good on his promises to bless his people accordingly. In Exodus 6:6, having remembered his covenant, he says to the people of Israel:

I am the LORD, and I will bring you out from under the yoke of the Egyptians. I will free you from being slaves to them, and I will redeem you with an outstretched arm and with mighty acts of judgment (cf. Lev 26:40–45).

Psalm 106:45 connects being remembered by God with God acting in grace and mercy: “For their sake he remembered his covenant, and showed compassion according to the abundance of his steadfast love” (NRSV; cf. Ps 98:3; 136:23–24).

In the New Testament, when Mary sings her famous song of praise to God in response to the news that she will give birth to “the Son of God” (Luke 1:35), she understands this event as God remembering his covenant: “He has helped his servant Israel, remembering to be merciful to Abraham and his descendants forever, just as he promised our ancestors” (Luke 1:54–55).

God not only remembers his covenant but also individuals within the covenant. There are several examples in the Old Testament of God remembering certain people in the sense that he acted on their behalf and in their best interests:

• In Genesis 19:29 the narrator explains the salvation of Lot from the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah in terms of God remembering Abraham: “So when God destroyed the cities of the plain, he remembered Abraham, and he brought Lot out of the catastrophe that overthrew the cities where Lot had lived.”

• In Genesis 30:22–23 God gave previously barren Rachel a child: “Then God remembered Rachel; he listened to her and enabled her to conceive. She became pregnant and gave birth to a son and said, ‘God has taken away my disgrace.’ ”

• In 1 Samuel 1:19–20 God similarly grants Hannah’s request for a child: “Early the next morning they arose and worshiped before the LORD and then went back to their home at Ramah. Elkanah made love to his wife Hannah, and the LORD remembered her. So in the course of time Hannah became pregnant and gave birth to a son. She named him Samuel, saying, ‘Because I asked the LORD for him.’ ”

As Wilson notes, “these examples show that God does not restrict his active remembrance to the people as a whole, but also responds to the individual cries of those among his people who call out to him.”35

In the Old Testament the cries of the covenant community and individuals within the covenant are regularly framed as calls for God to remember to act:36

Remember, LORD, what has happened to us; look, and see our disgrace. (Lam 5:1)

O LORD, how long will you forget me? Forever?

How long will you look the other way?

How long must I struggle with anguish in my soul,

with sorrow in my heart every day?

How long will my enemy have the upper hand? (Ps 13:1–2 NLT)

It is of course not the case that God always answers these cries with acts of deliverance. Nonetheless, the assumption of such prayers is that God knows us and is positively inclined to act on our behalf. As Gerald Wilson comments on the anguished fourfold “How long?” of Psalm 13, “such divine forgetfulness threatens to undo the psalmist, because to be known and remembered by God is to be in the relationship of blessing.”37 The general point is clear: being known by God means that he is attentive to our needs and acts in love and mercy toward us. If there are times when we feel that God has forgotten us, we may know with confidence that God remembers both his covenant and his people forever.

SAMPLE TEXTS: ISAIAH 49 AND MALACHI 3

God knows us as his children. God knows our names. God remembers us and acts towards us in love in keeping with his covenant promises. To round out our study of being known by God in the Old Testament, we consider two case studies in which these elements come together in striking ways. Both have a poignancy befitting descriptions of the intimate bond between God and his people that is signaled in being known by him.

Isaiah 49—God’s Tattoo

Isaiah 49:14–18 is a passage in which the Lord seeks to comfort his people who are languishing in exile. In Isaiah 49:13 the exiles are told that “the LORD . . . will have compassion on his afflicted ones” and that they should “shout for joy” and “rejoice” at the prospect, along with the heavens, the earth, and the mountains. Their response to this upbeat message is one of doubt and despondency: “But Zion said, ‘The LORD has forsaken me, the Lord has forgotten me’ ” (Isa 49:14).38 Sitting in exile, with Jerusalem in ruins, God’s people understandably feel abandoned by God. From their perspective, he has not remembered them. They see no sign of his compassion.

In Isaiah 49:15–18 the Lord seeks to quell their doubts and reassure them of his love and concern:

“Can a mother forget the baby at her breast

and have no compassion on the child she has borne?

Though she may forget,

I will not forget you!

See, I have engraved you on the palms of my hands;

your walls are ever before me.

Your children hasten back,

and those who laid you waste depart from you.

Lift up your eyes and look around;

all your children gather and come to you.

As surely as I live,” declares the LORD,

“you will wear them all as ornaments;

you will put them on, like a bride.” (Isa 49:15–18)

In verse 15, God’s attachment to his people is like that of a mother to a child, only more so. Walter Brueggemann explains:

It is completely improbable that a nursing mother would forsake her child, improbable but not impossible. For Yahweh, however, such forgetting and forsaking is not even a possibility, for Yahweh’s commitment and compassion are stronger and more intense than that of any nursing mother.39

Israel may feel forsaken and forgotten by God, but God says, “I will not forget you” (v. 15). God is even more attentive to his people than the most devoted mother to her children.

That God knows his people is affirmed vividly in Isaiah 49:16a: “See, I have engraved you on the palms of my hands.” The imagery recalls Isaiah 44:5, where people confess that they belong to the Lord and “write on their hand, ‘the LORD’s.’ ” As we have already seen, God knowing your name is analogous to being known by God and can signal belonging to God. Whatever you make of the art of tattooing, there are few more impressive symbols of one person’s love for someone else than a permanent bodily reminder. That God has “Israel” tattooed on his hands leaves beyond any doubt that he will remember his people and that he knows their names.

The second half of Isaiah 49:16 compares God to an architect who thinks constantly about his plans: “your walls are ever before me.” The literal meaning is that God plans to rebuild and reclaim the city of Jerusalem. Next, the Lord announces that Zion’s children will return to her in overflowing numbers: “you will wear them all as ornaments” (v. 18a). Zion will be like a happy mother whose children have returned. Zion will also be like a father who is exceedingly proud of his daughter at her wedding: “you will put them on, like a bride” (v. 18b). As Barry Webb notes, “the images [here] are mixed and do not always cohere logically, but they all affirm God’s love for his people and his tireless commitment to their welfare.”40

“Tattoos were quite common in the ancient world. People got tattoos for different reasons. Egyptian women tattooed their stomachs and breasts during pregnancy to ensure a safe birth. Slaves got tattoos to identify them as the property of another. Criminals were sometimes forced to get a tattoo to bear the stigma of their crime. The Greeks and Romans got a tattoo to show allegiance to their god. For instance, King Ptolemy IV tattooed his body with ivy leaves to show his devotion to Dionysus, the god of wine. God’s tattoo is probably similar to Ptolemy’s, only God turns the meaning on its head. While Ptolemy and other kings were running around flaunting their devotion to their god—your God sits on his throne and declares, ‘I’m devoted to you! And I’ve put my palms under the needle to prove it.’ ”

Preston Sprinkle41

With God’s city of Zion in ruins and the identity of the exiled people of God in tatters, God assures the Israelites that they belong to him and that he is lovingly attentive to them as a mother to her children. At the heart of God’s reassurances in Isaiah 49 are two themes associated with being known by God in the Old Testament: a comparison of God to a devoted parent and the names of God’s people etched into his very being.

Malachi 3—A Scroll of Remembrance

At several points in the Old Testament, the arrogance and prosperity of those who do not honor God is a stumbling block to those who do, which causes them to question the goodness of God. Psalm 73 is one example:

Surely God is good to Israel,

to those who are pure in heart.

But as for me, my feet had almost slipped;

I had nearly lost my foothold.

For I envied the arrogant

when I saw the prosperity of the wicked. (Ps 73:1–3)

A similar sentiment is expressed in Malachi 3:13–15, which reports some people saying that there is no point in serving God, obeying his commands, or fasting and repenting. Worse still, those who turn their backs on God seem to be getting away with it:

“You have spoken arrogantly against me,” says the Lord. “Yet you ask, ‘What have we said against you?’ “You have said, ‘It is futile to serve God. What do we gain by carrying out his requirements and going about like mourners before the LORD Almighty? But now we call the arrogant blessed. Certainly evildoers prosper, and even when they put God to the test, they get away with it.’ ”

Those who do seek the Lord are understandably discouraged by this state of affairs. Doesn’t God notice when people flout his authority? Is there no difference between those who are faithful to him and those who are not? The issue strikes at the heart of their identity as the people of God. Are they special to him? Does he notice their efforts to live in faith and obedience?

Their first response is to talk things over: “Then those who feared the LORD talked with each other” (Mal 3:16a). While we are not privy to their conversation, Taylor and Clendenen make some plausible suggestions as to what might have been said:

The content of their speech may have been words of repentance or spiritual encouragement to one another in view of the ruined crops (see Prov 27:17; Jer 31:34). Perhaps they were words of encouragement to do right, such as those of the leprous men in 2 Kgs 7:9—Then they said to each other, “We’re not doing right. This is a day of good news and we are keeping it to ourselves. Let’s go at once and report this to the royal palace” (see also Jer 36:16). Or perhaps they were simply “speaking the truth to each other, and rendering true and sound judgment in their courts” (Zech 8:16).42

Whatever the exact nature of their discussion, “the LORD listened and heard.” Moreover, “a scroll of remembrance was written in his presence concerning those who feared the LORD and honored his name” (Mal 3:16).

The best background against which to understand this “scroll of remembrance” is God as “the divine King surrounded by his heavenly servants instructing a scribe to record an event in the royal archives.”43 Esther 2:23 notes a recording “in the book of the annals in the presence of the king.” In Esther 6:1 “the book of the chronicles, the record of his reign” is ordered for the king. And, in Ezra 5:17 a search of the “royal archives” takes place. As Taylor and Clendenen note, “records of decisions, actions, accomplishments, and various memorable events were kept by royal officials in the ancient world.”44 Significantly, Malachi 1:14 describes God as “a great king,” whose name is to be “feared among the nations.”

The scroll of remembrance is not the same as the book of life, that heavenly register of the faithful (see above in this chapter). Nor is it the record of the deeds of the unrighteous from which God will mete out justice (cf. Dan 7:10; Rev 20:12). Rather, it is “an ongoing account of the words and deeds of the God-fearers.”45 Those who sought to honor God’s name needed reassurance that God knew of their plight and that he was taking notice. The same sentiment is present in Psalm 56 where the enemies of the psalmist “are in hot pursuit” (v. 1), and he asks God to “record my misery; list my tears on your scroll—are they not in your record?” (v. 8).

“Helen Bamber, the British campaigner for the care of torture victims, has described the experience of holding a dying woman in her arms after the liberation of the Belsen concentration camp at the end of World War II. As the woman rasped out the horrific account of her experiences in the camp, Bamber said to her: ‘I am going to tell your story.’ This seemed to calm the distressed woman. ‘I think she knew she was going to die,’ Bamber said. ‘She didn’t want to die and [her story] not be told—that nobody would know.’ This was a woman anxious, even at her death, not to be ignored or forgotten. When all other desires have left us or become irrelevant, we are left with the desire to be acknowledged, identified, appreciated, and remembered.”

Hugh Mackay46

In response to the concern of the faithful that God had not noticed the injustice in their day and their own determination to obey him, “there was written down in a book a record of those who feared the LORD and respected him” (Mal 3:16 GNT). As a further encouragement, the Lord declares his intention to confirm the identity of those who fear him:

“On the day when I act,” says the LORD Almighty, “they will be my treasured possession. I will spare them, just as a father has compassion and spares his son who serves him. And you will again see the distinction between the righteous and the wicked, between those who serve God and those who do not.” (Mal 3:17–18)

It is common for people to question their identity in times of hardship and difficulty. In God’s response to such a situation in Malachi 3:16–18, we see the same cluster of ideas that we have noted throughout our study of being known by God in the Old Testament: God’s people are those to whom he is attentive—a “scroll of remembrance was written in his presence concerning those who feared the Lord”; they belong to him as his “treasured possession”; and he knows them and relates to them as a father who has compassion on his son (Mal 3:16-18).

The four Gospels in the New Testament are testimony to the fact that the genre of biography goes back to the ancient world. And the first-century Jewish historian Josephus is an early example of someone who wrote his autobiography. However, interest in life stories has never been stronger than in our own day, with politicians, actors, and sports stars leading the way. Ordinary people too are keen to preserve the record of their lives, with social media providing unprecedented opportunities to share everything from the mundane to the profound and extraordinary. Motivations vary. Some wish to bring attention to their accomplishments or unusual experiences, others to record their journey through illness or tragedy. Many wish to pass on their story to subsequent generations of their families. Malachi 3:16 indicates that God is writing the biographies of those who honor his name.

Whereas the knowledge of God might sometimes seem ethereal and removed from our daily lives, the fact that we are known by God even in our darkest days is a great comfort. God knows us when our struggles with our own identity feel hidden from everyone else.

BEING KNOWN BY GOD AND PERSONAL IDENTITY

This chapter opened with a critique of the view that personal identity is a do-it-yourself project. The problem with “defining yourself” is that it ignores the fact that we are social creatures. The self as an autonomous individual does not exist. We are in large measure defined by our relationships. And we come to know ourselves in being known by others.

With this in mind, it is significant, as we saw in chapter two, that one of the Bible’s answers to the question of personal identity is that human beings are those who are known by God, those about whom God is mindful (Job 7:17; Pss 8:4; 144:3). And when David asks, “Who am I?” he comes to the conclusion that he is known by God (2 Sam 7:20; cf. 1 Chr 17:18). In contrast to Descartes’s dictum, “I think, therefore I am,” or “I know, therefore I am,” the Bible puts things the other way around: “I am known, therefore I am.”47

What does it mean to be known by God? And how does being known by God contribute to your personal identity? Our investigation of the theme of being known by God in the Old Testament reveals that to be known by God means to belong to God and to be chosen by him. He knows us intimately and personally and with the love and compassion of a father or mother for their child. He remembers us when we are in trouble, and he knows our name. Being known by God meets our need to be recognized and acknowledged in the most profound manner. Our identity as his children is grounded and sustained by his constant attentiveness. There is indeed something reassuring and beautiful about God really knowing you.

Who am I? I am known and loved by God as his child. In chapter seven, we will consider what the New Testament says about being known by God.

RELEVANT QUESTIONS

1. There is indeed something reassuring and beautiful about someone really knowing you. Do you have people in your life who really know you? How can close relationships be a source of comfort in both good and bad times?

2. “What matters supremely is not . . . that I know God, but the larger fact . . . that he knows me,” says J. I. Packer. How can being known by God as his child foster a “healthy sense of significance” and “a secure state of mind” (McLean and Rosner)?

3. What is the story behind your naming, and how do you feel about your name? The words of the old hymn speak of God’s remembrance of us: “My name is graven on his hands; my name is written on his heart.” What is the significance of being named by God, now and into eternity?

4. In times of hardship and difficulty, it is common for people to question God’s goodness and attentiveness. How can God’s response to his discouraged followers in Malachi be an encouragement or comfort to us?

1. Both quoted in John Elder, “We Are Who We Believe We Are,” Sunday Age (June 21, 2015), 8.

2. In response to such trends, the social sciences are increasingly defining personhood in relational terms. Far from recommending that we “find ourselves,” such researchers argue that “the self is too complexly configured to be accessible to a single finite mind inquiring into itself by itself” (David A. Jopling, Self Knowledge and the Self [New York: Routledge, 2000], 137).

3. Jopling, Self Knowledge and the Self, 166.

4. Sun Herald, November 22, 2013.

5. Michael Allen Fox, “We’re Self-obsessed—But Do We Understand the Nature of the Self?” The Conversation, August 31, 2004, http://theconversation.com/were-self-obsessed-but-dowe-understand-the-nature-of-the-self-30912.

6. Michael Horton, The Christian Faith: A Systematic Theology for Pilgrims on the Way (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011), 87.

7. Hans Walter Wolff, Anthropology of the Old Testament, trans. Margaret Kohl (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1974), 1–2.

8. I am not assuming that all of the findings from this chapter about the people of God in the Old Testament apply to God’s people in the New Testament. While it is safe to say that the blessings of the New Covenant are never eclipsed by those of the Old, the following chapter will test the continuity between the testaments on the theme of being known by God.

9. Meister Eckhart, Sermons and Treatises, vol. 1 (London: Watkins, 1981), 165.

10. William J. Mander, “Does God Know What It Is Like to Be Me?,” Heythorp Journal 43.4 (2002): 430–43.

11. Hawani Tola, Ridley College student, social media post (March, 2015).

12. See also the juxtaposition of omniscience and omnipresence in Ps 139:1–4, “You know when,” followed by vv. 5–10, “You hem me in.”

13. Justin Thacker, “A Biblical Account of Christian Knowing,” Ethics in Brief 13.1 (2008): 1.

14. Thacker, “A Biblical Account of Christian Knowing,” 2.

15. My own interest in the subject began with an article on isolated remarks in two twentieth-century authors: “Known by God: C. S. Lewis and Dietrich Bonhoeffer,” Evangelical Quarterly 77.4 (2005): 343–52.

16. J. I. Packer, Knowing God, 20th Anniversary ed. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993), 41–42. Emphasis added.

17. See also NJB: “The Lord knows those who are his own.” Twice in Numbers 16 the same thought is expressed with the verb to “choose,” a connection we will explore in the next subsection. The one the Lord chooses will be saved (vv. 5 and 7).

18. Walther Eichrodt, Theology of the Old Testament: Volume Two (London: SCM, 1967), 292, commenting on Hos 13:5.

19. German: “Gottes Eigentum.” Adolf Schlatter, Paulus, der Bote Jesu: Eine Deutung seiner Briefe an die Korinther (Stuttgart: Calwer, 1985; orig. 1934), 253.

20. F. F. Bruce, The Epistle to the Galatians: A Commentary on the Greek Text, NIGTC (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982), 202.

21. John Calvin, Calvin’s New Testament Commentaries: 1 Corinthians (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996), 173.

22. See also Roy E. Ciampa, “Adoption,” in New Dictionary of Biblical Theology, ed. T. D. Alexander and B. S. Rosner (Leicester, UK: Inter-Varsity Press, 2000), 376.

23. Loyola McLean and Brian S. Rosner, “Theology and Human Flourishing: The Benefits of Being Known by God,” in Beyond Well-Being: Spirituality and Human Flourishing, ed. Maureen Miner, Martin Dowson, and Stuart Devenish (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing, 2012), 65–83.

24. McLean and Rosner, “Theology and Human Flourishing,” 67.

25. Ibid., 68.

26. Ibid., 73.

27. Ibid., 80.

28. John Muddiman, The Epistle to the Ephesians, BNTC (London: Continuum, 2001), 166–67.

29. Leon Morris, The Book of Revelation, TNTC (Leicester, UK: Inter-Varsity Press, 1987), 68.

30. Timothy Keller, The Reason for God: Belief in an Age of Skepticism (New York: Penguin: 2008), 78.

31. In Hebrews 12:23, having your name “written in heaven” is synonymous with being a member of “the church of the firstborn,” suggesting once again a link between divine adoption and being known by God.

32. Thomas W. Davis, “Book, Book of Life,” in Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology, ed. Walter A. Elwell, electronic ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1996).

33. The Hebrew has simply yadah, God “knew,” with the object of the verb unexpressed; see also ASV, God “took knowledge of them.” The NIV translation, God “was concerned about them,” along with most modern translations, understands the object to be the dire situation of the Israelites. See also the NET note: “The idea seems to be that God took personal knowledge of, noticed, or regarded them.” A similar use of the verb “to know” appears in Exod 3:7 NIV: “The LORD said, ‘I have indeed seen the misery of my people in Egypt. I have heard them crying out because of their slave drivers, and I am concerned about [literally, know] their suffering.’ ” We will return to Exod 2:25 in chapter thirteen in connection with the comfort that being known by God brings.

34. Lindsay Wilson, “Remembered by God” (Unpublished paper; Ridley College Theology Conference: Known by God, 29–30 May 2015).

35. Wilson, “Remembered by God.”

36. Prayers for the people: Exod 32:13; Deut 9:27; 2 Chr 6:41–42; Neh 1:8–9; Pss 74:2–3; 132; Jer 14:21. Prayers of individuals: Judg 16:28; 2 Kgs 20:3; Neh 5:19; Pss 25:7; 106:4; Jer 15:15.

37. Gerald H. Wilson, Psalms, Volume 1, NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2002), 278.

38. As Barry Webb explains, “Zion” is code for the people of God: “Zion is not just the city of that name, it is its people. Zion is not simply their home, it is their name, their identity” (The Message of Isaiah, Bible Speaks Today [Leicester, UK: Inter-Varsity Press, 1996], 196).

39. Walter Brueggemann, Isaiah 40–66, Westminster Bible Companion (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1998), 116.

40. Webb, Message of Isaiah, 196.

41. Preston Sprinkle, Charis: God’s Scandalous Grace for Us (Colorado Springs: David C. Cook, 2014), 112.

42. Richard A. Taylor and E. Ray Clendenen, Haggai, Malachi: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture, NAC 21A (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 2004), 442–43.

43. Ibid., 443.

44. Ibid.

45. Andrew Hill, “Malachi,” in Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary, ed. John W. Walton, vol. 5 (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2009), 241.

46. Hugh Mackay, What Makes Us Tick: The Ten Desires that Drive Us (Sydney: Hachette Australia, 2010), 4.

47. See N. T. Wright, who offers a similar revision of Descartes’s dictum claiming the support of the apostle Paul, suggesting, “I am loved, therefore I am” (Paul: In Fresh Perspectives [London: SPCK, 2006], 173).