CHAPTER 7

KNOWN BY GOD AND CHRIST IN THE NEW TESTAMENT

At one point in C. S. Lewis’s The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, one of the books in The Chronicles of Narnia series, Eustace Clarence Scrubb wanders off to avoid doing his chores and enters a dragon’s cave. Greedily plundering its treasures, he finds himself turned into a dragon. Aslan the lion comes to his rescue and “undragons” him, which results in the transformation of the odious Eustace into “a different boy.” Following the incident, Eustace asks his cousin Edmund what he knows of Aslan: “But who is Aslan? Do you know him?” Edmund admits to knowing Aslan, but the beginning of his answer is inverted in a surprising way: “Well, he knows me.”1 According to Edmund, being known by Aslan is more important than knowing Aslan.

The same applies when it comes to the knowledge of God. God knows us better than we know him, and his knowledge of us precedes and is the basis for our knowledge of him.

Our investigation of the theme of being known by God in the Old Testament in chapter six showed it to be a highly personal truth with deep theological roots. Being known by God characterizes how God related to the nation of Israel as well as to the main characters in salvation history. It connects to several of God’s principal saving actions in the Old Testament including the redemption of his people from slavery in Egypt and the establishment of kingship. It has links with Israel’s adoption as God’s son and the adoption of the Davidic king as God’s son. And it emphasizes God’s compassionate concern for his people as a loving parent who is attentive to and cares for his children.

What does the New Testament say about the theme of being known by God? Does it have the same shape as in the Old Testament? How important is the theme of being known by God in the New Testament? Is there something reassuring and beautiful about being known by God in the New Testament? What does it contribute to our study of personal identity?

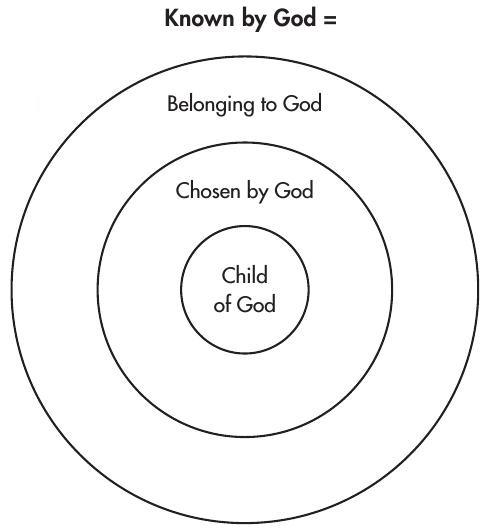

As it turns out, when it comes to the theme of being known by God, there is remarkable consistency between the testaments. Being known by God defines what it means to be a Christian in much the same way it did to be part of Israel as the people of God: those who are known by God belong to God, are chosen by God, and are adopted into his family as his children. However, the New Testament takes things further and develops the theme in two main ways: first, being known by God’s Son, Jesus Christ, becomes critical; and second, being known by God and Christ emerges as a defining feature of life in the age to come.

We begin our study of the New Testament with a general look at being known by God, before moving to the idea of being known by Christ. A third major section considers a key New Testament text for our theme, namely the Gospel of John.

THE PRIMACY OF BEING KNOWN BY GOD

As social creatures, we are defined by our relationships. It is thus no surprise that the Bible makes a big deal about the utterly transforming experience and inestimable privilege of knowing God. The prophet Jeremiah declared that knowing the God of kindness, justice, and righteousness is of greater value than having wisdom, strength, and riches: “Let the one who boasts boast about this: that they have the understanding to know me” (Jer 9:23–24). In Philippians, Paul wrote of the “surpassing worth of knowing Christ Jesus my Lord” (3:8). And according to Jesus himself, “This is eternal life: that they know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom you have sent” (John 17:3).

Notwithstanding the great blessing that it is to know God, on three occasions in Paul’s letters the apostle insists that being known by God is even better. In Galatians 4:8–9 Paul reminds gentile Christians of their previous plight before affirming their current blessed status:

Formerly, when you did not know God, you were slaves to those who by nature are not gods. But now that you know God—or rather are known by God. . . .

At first Paul writes of believers knowing God, but then he offers, in the words of F. F. Bruce, a “swift correction.”2 The words “or rather”3 make it clear that what really matters for the identity of the Christians in Galatia is the fact that they are known by God.

Two other texts that underscore the critical importance of being known by God are in 1 Corinthians. First Corinthians 8:1–3 contain the opening remarks of Paul’s lengthy discussion of food offered to idols in chapters eight to ten. Apparently certain Corinthians felt that their knowledge of God and the fact that “an idol is nothing at all in the world” (1 Cor 8:4) meant that they were free to eat food originally sacrificed to idols under any circumstances. Paul warns them about the dangers of becoming proud in their knowledge:

Now about food sacrificed to idols: We know that “We all possess knowledge.” But knowledge puffs up while love builds up. Those who think they know something do not yet know as they ought to know. (1 Cor 8:1–2)

As the alternative to pride, which “puffs up” or “builds up” only oneself, Paul recommends love, which “builds up” others.

A number of commentators have noticed that the next verse contains a surprising twist: “But whoever loves God is known by God” (1 Cor 8:3). Whereas we might expect Paul to say, “whoever loves God, knows God,” Paul turns things around. The knowledge that counts is not our knowledge of God, but his knowledge of us.4

“Let me know you, for you are the God who knows me; let me recognize you as you have recognized me.”

Saint Augustine5

At the end of his famous poem in praise of love in 1 Corinthians 13, Paul contrasts knowing God with being known by him:

For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known [by God]. (1 Cor 13:12)6

When it comes to knowledge of God, we will only have “complete mutuality of knowledge”7 when Christ returns and we see him face to face. In the meantime, we “know in part,” indirectly as it were, “as in a mirror.” We know God truly, but our knowledge of him is hardly exhaustive or complete. God, on the other hand, knows us perfectly and far better than we know him. Paul in 1 Corinthians 13:11 suggests that our knowledge of God is like that of a young child knowing his or her parent. Just as parents know their children much better than the other way around, so God’s knowledge of us is much greater than our knowledge of him.

“The consummation of all things [in 1 Corinthians 13:12] consists in the fact that the cleft between knowing and being known by God is abolished.”

Gunther Bornkamm8

The importance of being known by God is also underscored in the New Testament with reference to its role on the day of judgment. This is most clear in not being known by Christ on that day, which we will discuss in the next section. It is also relevant to another text in 1 Corinthians in connection with whether or not one is known by God. In 1 Corinthians 14:37–38 Paul issues a grave warning to members of the Corinthian church who perceive themselves to have a gift of discernment with respect to Paul’s instructions:

If anyone thinks they are a prophet or otherwise gifted by the Spirit, let them acknowledge that what I am writing to you is the Lord’s command. But if anyone ignores this, they will themselves be ignored.

Verse 38 contains a memorable play on words repeating the verb “to ignore”: ignoring Paul will result in being ignored. The question is, ignored by whom, by God or by someone else? Barrett thinks Paul means that he “does not recognize the man in question as inspired in his opinion, not that he does not recognize him as a Christian.”9 However, the tone of the passage points to a more serious threat. Accordingly, we might translate it: “anyone who disregards (it [i.e., Paul’s teaching]), is disregarded (by God).”10 In other words, Paul intends a covert allusion to God’s judgment.

Hays points to similar scriptural statements “announcing God’s eschatological punishment on those who reject the word of God,” where the terms of judgment correspond to the original rejection by the person being judged:11

You have rejected the word of the LORD, and the LORD has rejected you as king over Israel! (1 Sam 15:26)

If anyone is ashamed of me and my words in this adulterous and sinful generation, the Son of Man will be ashamed of them when he comes in his Father’s glory with the holy angels. (Mark 8:38)

Paul is in no doubt writing concerning the divine authority of his message. To deny the prophetic authority of Paul’s teaching would not only undermine his authority, but would also reveal that person to be at odds with God. Since what Paul is writing is “the Lord’s command” (1 Cor 14:37), to “ignore” it would be tantamount to a denial of the confession that “Jesus is Lord” (1 Cor 12:1–3).12 To be ignored or not known by God in 1 Corinthians 14:38 is the appropriate punishment for ignoring God and is the equivalent of final rejection by God.13

WHAT IT MEANS TO BE KNOWN BY GOD

Being known by God in the New Testament is equivalent to (1) belonging to God; (2) being chosen by God; and (3) being a child or son of God. These are the same three definitions of being known by God that we encountered in the Old Testament. As in the Old Testament, they are not three discrete notions. Instead they represent more or less specific angles on the identity of being a child of God, which is the heart of the matter (see diagram).

In defining being known by God in the New Testament, texts from Paul’s letters are most enlightening.

Belonging to God

As we saw in chapter six, being known by God is in some contexts the equivalent of belonging to God. We see the same in 2 Timothy 2:16–19, which quotes Numbers 16:5 in the context of God making a division between the faithful and those who have departed from the truth:

Avoid godless chatter, because those who indulge in it will become more and more ungodly. Their teaching will spread like gangrene. Among them are Hymenaeus and Philetus, who have departed from the truth. They say that the resurrection has already taken place, and they destroy the faith of some. Nevertheless, God’s solid foundation stands firm, sealed with this inscription: “The Lord knows those who are his,” and, “Everyone who confesses the name of the Lord must turn away from wickedness.” (2 Tim 2:16–19)

Paul reassures the Christians in Ephesus that obeying the truth and seeking to behave in a godly manner matters to God and does not escape his notice. While at times it may seem that there is no distinction between those who trust God and those who do not, believers rely on the fact that God knows those who belong to him. The quotation from Numbers 16:5 could hardly be given more prominence in the passage; that “the Lord knows those who belong to him” seals God’s solid and firm foundation upon which believers may confidently build their lives. Conversely, by implication God does not know the false teachers who deny the truth, and they do not belong to him.

Chosen by God

Being known by God also overlaps with the concept of divine election. In Romans 8:29 Paul forges a connection between being known by God and being chosen by him with just one word: the verb “to foreknow.” In Romans 8:28 Paul famously declares that “in all things God works for the good of those who love him.” In verses 29–30 he explains that those who love God are those whom God foreknew, predestined, called, justified, and glorified. Some have called this “the golden chain of salvation,” five unbreakable links in a sequence that spell out the historical outworking of the love of God toward the elect and the grounds of our unshakeable confidence in that love. Foreknowledge stands at the beginning of the series and refers to God knowing and loving us in advance. The Greek lexicon BDAG defines the word translated “foreknew,” proginōskō, as “know beforehand” or “choose beforehand.”14 Paul uses the word as a synonym for divine election.

God’s eternal purpose and love are apparent in the broader context of Romans 8, with the love of God for his people appearing climactically in v. 39 as the complement to the description of believers in v. 28 as those who love God. Both the love of God and predestination are crystallized in the notion of being foreknown by God; to be known by God is to be loved and chosen by him. This can also be seen in Paul’s use of the word “foreknew” in Romans 11:2 where his answer to the question of whether God has abandoned the people of Israel is that “God did not reject his people, whom he foreknew”; or we could paraphrase it as “those whom he knew and set his love upon in advance.”

Son of God

Two passages from Paul’s letters associate being known by God with being sons of God. The broader context of Romans 8:29, being foreknown by God, includes no less than three references to adoption. First, Israel’s “adoption to sonship” appears at the head of Paul’s list of the nation’s privileges in Romans 9:4. Second, in 8:15 believers in Christ receive “adoption to sonship” and cry “Abba, Father” by the Spirit. Third, and most importantly for our purposes, the goal of the predestination to which those whom God foreknew are bound in Romans 8:29 is “to be conformed to the image of his Son, that he might be the firstborn among many brothers and sisters.” This verse juxtaposes being (fore)known by God and being adopted by God.

The two great moments of adoption in the Old Testament were God’s adoption of the nation of Israel and of the kings in the line of David. In Romans 8:29 the two come together in their New Testament fulfillment: the sonship of the new people of God is by virtue of God’s unique Son! As Paul puts it in Ephesians 1:5, “he predestined us for adoption to sonship through Jesus Christ.”

The second New Testament text to connect being known by God to adoption is Galatians 4:8–9. Most English Bibles start a new section with Galatians 4:8; the NIV for example gives 4:8–20 the heading, “Paul’s Concern for the Galatians.” However, there are good reasons not to separate 4:8–9 from the preceding verses.

In Galatians 3:23–4:7, Paul expounds the doctrine of God’s adoption of believers in Christ. In the NIV the section is accurately entitled, “Children of God,” for these verses are indeed the longest exposition of adoption in the Bible. On no less than four occasions, Paul tells the Galatian Christians that they are sons or children of God (3:26; 4:6; 4:7 [twice]):

For in Christ Jesus you are all sons of God through faith. . . . But when the appropriate time had come, God sent out his Son, born of a woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we may be adopted as sons with full rights. And because you are sons, God sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, who calls “Abba! Father!” So you are no longer a slave but a son, and if you are a son, then you are also an heir through God. (Gal 3:26; 4:4–7 NET)15

“As soon as Paul had declared that the Galatians who formerly knew not God had come to know God, he immediately inverted his statement and added a rhetorical correction—‘or rather are known by God.’ Paul was here clearly distinguishing the Christian understanding of salvation from the gnostic doctrine of revelation. Just as our adoption by the Father precedes his imparting of the Holy Spirit and our responsive cry, “Abba!” so also our knowing God is conditioned upon his prior knowledge of us.”

Timothy George16

When Paul describes the Galatian Christians in Galatians 4:8–9 as those who are known by God, he has not left the theme of adoption behind. The fact that the slavery/freedom motif of 4:1–2, 7 is carried forward in 4:8–9 supports this contention. Paul’s preference for “being known by God” over “knowing God” in Galatians 4:8–9 as a description of them is thus perfectly explicable: it fits better with their identity as sons of God, which Paul has just spent so much time expounding.

KNOWN BY CHRIST

The New Testament broadens our understanding of what it means to be known by God in one unmistakable way: believers are not only known by God, but are also known by Jesus Christ.

The theme of being known by Christ will prove to be of critical importance as our study proceeds. In the chapters following, we will see that our personal identity is inextricably tied up with Jesus Christ and with his identity. The defining moments of his life define our lives as well. And his destiny is our destiny. To begin laying the foundations for these profound and weighty matters, we will consider two things about being known by Christ in this section: (1) the extent of Christ’s knowledge of us; and (2) the role of being known by Christ at the last judgment.

Jesus Christ Knows Us Intimately and Personally

Revelation 2–3 contains a series of brief letters from the risen Christ to seven churches. The letters have an identical fourfold structure, as George Beasley-Murray explains:

(1) an introductory statement from the risen Christ, drawn from the opening vision [in Rev. 1] and usually pertinent to the contents of the letter; (2) praise for the good qualities of the church and/or criticism of its faults; (3) a promise to the victor relating to the blessings to be bestowed in the kingdom of Christ; and (4) an exhortation to listen to what the spirit is saying to the churches.17

All seven of the churches faced considerable challenges. Following the introductory statement, significantly for our purposes each letter begins with the same two words from the Lord Jesus: “I know.” Recognition and acknowledgement are among the first things that a person in difficulty needs. In the cases of five of the churches in Asia Minor, Jesus knows their perseverance, afflictions, poverty, faithfulness, love, faith, and service:

The Church in Ephesus

I know your deeds, your hard work and your perseverance. I know that you cannot tolerate wicked people, that you have tested those who claim to be apostles but are not, and have found them false. You have persevered and have endured hardships for my name, and have not grown weary. (Rev 2:2–3)

The Church in Smyrna

I know your afflictions and your poverty—yet you are rich! I know about the slander of those who say they are Jews and are not, but are a synagogue of Satan. (Rev 2:9)

The Church in Pergamum

I know where you live—where Satan has his throne. Yet you remain true to my name. You did not renounce your faith in me, not even in the days of Antipas, my faithful witness, who was put to death in your city—where Satan lives. (Rev 2:13)

The Church in Thyatira

I know your deeds, your love and faith, your service and perseverance, and that you are now doing more than you did at first. (Rev 2:19)

The Church in Philadelphia

I know your deeds. See, I have placed before you an open door that no one can shut. I know that you have little strength, yet you have kept my word and have not denied my name. (Rev 3:8)

Like the “book of remembrance” in Malachi 3 (see chapter six), Jesus reassures the churches that he knows them in their suffering and is attentive to their plight. And like the new names given to God’s people in Isaiah 56, 62, and 65 (see “Naming as Knowing” in chapter six), God promises to the church in Pergamum a new name: “To the one who is victorious. . . . I will also give that person a white stone with a new name written on it, known only to the one who receives it” (Rev 2:17).

“Jesus is promising to each faithful disciple, to each one who ‘conquers,’ an intimate relationship with himself in which Jesus will use the secret name, which, as with lovers, remains private to those involved.”

N. T. Wright18

Boxall notes the color “white functions elsewhere in Revelation as the color of heaven (1:14; 14:14; 20:11) and of victory (3:4–5, 18; 6:2, 11; 7:9, 13; 19:14).”19 Whatever else the “new name” implies, its hidden nature, known only to God and its bearer, speaks of intimate, interpersonal relationship, a knowledge that would encourage the one who overcomes to persevere. Being given a secret name by God is another way of affirming that a person is known by God.20 The value of being known in our afflictions will be a focus in chapter thirteen when we consider the comfort of being known by God.

What Jesus knows of the other two churches is less comforting:

The Church in Sardis

I know your deeds; you have a reputation of being alive, but you are dead. (Rev 3:1)

The Church in Laodicea

I know your deeds, that you are neither cold nor hot. I wish you were either one or the other! So, because you are lukewarm—neither hot nor cold—I am about to spit you out of my mouth. (Rev 3:15–16)

With respect to the church in Sardis, as in Malachi 3, a distinction “between those who serve God and those who do not” (Mal 3:18) is fundamental to being known by Christ. Jesus warns some of those in Sardis to repent: “But if you do not wake up, I will come like a thief, and you will not know at what time I will come to you” (Rev 3:3). As we discovered in chapter five, you can be known about without being known (in the sense of being known intimately and personally). Jesus’s words to those who are “dead” in Sardis are the equivalent of a call to repentance and faith and indicate that they are not yet known by him in the fullest sense. To others in Sardis, Jesus offers more reassuring words that confirm their identity as those who belong to him: “Yet you have a few people in Sardis who have not soiled their clothes. They will walk with me, dressed in white, for they are worthy” (Rev 3:4).

In the case of the church of Laodicea, Jesus delivers a confronting message of correction: “I counsel you to buy from me gold refined in the fire, so you can become rich; and white clothes to wear, so you can cover your shameful nakedness; and salve to put on your eyes, so you can see” (Rev 3:18). Jesus’s knowledge of them enables him to rebuke them as a father would correct his son: “Those whom I love I rebuke and discipline” (Rev 3:19).21

We learn one more thing about being known by Jesus in the letters to the seven churches: to be known intimately and personally by Jesus leads to knowing Jesus. Each letter begins with a revealing description of Jesus:

These are the words of him who holds the seven stars in his right hand and walks among the seven golden lampstands. (Rev 2:1)

These are the words of him who is the First and the Last, who died and came to life again. (Rev 2:8)

These are the words of him who has the sharp, double-edged sword. (Rev 2:12)

These are the words of the Son of God, whose eyes are like blazing fire and whose feet are like burnished bronze. (Rev 2:18)

These are the words of him who holds the seven spirits of God and the seven stars. (Rev 3:1)

These are the words of him who is holy and true, who holds the key of David. (Rev 3:7)

These are the words of the Amen, the faithful and true witness, the ruler of God’s creation. (Rev 3:14)

To the faithful in the church in Thyatira Jesus promises: “I will also give that one the morning star” (Rev 2:28). N. T. Wright regards this as another indication of the intimacy that Jesus offers his disciples: “He will share his very identity with them.”22 Indeed, later in Revelation we learn that “the bright Morning Star” is Jesus himself (Rev 22:16).

Known and Not Known at the Last Judgment

The critical importance of being known by Christ is nowhere better seen than in three last judgment scenes in the Synoptic Gospels. In each case, the concluding solemn verdict of condemnation includes the denial by Jesus the Judge of ever having known the individuals concerned:

The Sermon on the Mount, in the judgment of false prophets by their fruit:

“Then I will tell them plainly, ‘I never knew you. Away from me, you evildoers!’ ” (Matt 7:23)

The parable of the ten virgins, in response to the foolish virgins:

“He replied, ‘Truly I tell you, I don’t know you.’ ” (Matt 25:12)

The parable of the narrow door, in response to those knocking outside:

“He will reply, ‘I don’t know you or where you come from. Away from me, all you evildoers.’ ” (Luke 13:27)23

In all three texts the seriousness of Jesus’s not knowing those he condemns is reinforced by various means, including their description as “evildoers,” Jesus’s insistence that his words must not be taken lightly (he speaks the truth, “plainly”) and the stern words of dismissal, “Away from me.”

Three more texts underscore not only the tragedy of some not being known at the last judgment but also the joyful reassurance of others being known by him on that day:

Whoever acknowledges me before others, I will also acknowledge before my Father in heaven. But whoever disowns me before others, I will disown before my Father in heaven. (Matt 10:32–33)

I tell you, whoever publicly acknowledges me before others, the Son of Man will also acknowledge before the angels of God. But whoever disowns me before others will be disowned before the angels of God. (Luke 12:8–9)

The one who is victorious will, like them, be dressed in white. I will never blot out the name of that person from the book of life, but will acknowledge that name before my Father and his angels. (Rev 3:5)24

Making Jesus’s not knowing someone the decisive criterion of judgment is particularly disturbing. The verdict “I never knew you” is highly personal, shatteringly brief, yet comprehensive, and it places the decision fully out of the reach of the person being condemned. What can they do about not being known? Any appeal against this judgment would be futile. Davies and Allison refer to “I never knew you” as a formula of renunciation equivalent to “I never recognized you as one of my own.”25

In terms of other New Testament depictions of the last judgment, to be told “I never knew you” ranks alongside the great white throne judgment of Revelation 20 for severity. In that passage, people are condemned for not having their name written in the book of life, a synonym for not being known by God. This situation underscores the grace of God as the sole grounds for those who are saved; you can hardly take any credit for having your name in a list compiled before you were born or for being known by Christ (see chapter twelve on “Humility”).

SAMPLE TEXT: THE GOSPEL OF JOHN

Knowing Christ and being known by him is a major theme in John’s Gospel and makes a substantial contribution to a biblical theology of personal identity. To trace the theme, we will follow two strategies that I generally recommend for reading the Fourth Gospel:

• Read John with the prologue (John 1:1–18) and the purpose statement (John 20:30–31) in mind;

• Read John cumulatively.

The Prologue and Purpose Statement

John’s prologue, 1:1–18, is a remarkably effective introduction to the Gospel of John. The major themes of John are introduced in the prologue, especially the identity and mission of Jesus, his rejection by Israel, and the blessings of faith in him. In addition, Mark Stibbe points out that the main movements of the Gospel’s plot are also anticipated in the prologue:

Many scholars have noticed that vv. 10–13 encapsulate the plot of the whole Gospel. Verses 10–11 point to the lack of recognition of Jesus and to his rejection by his own race in chs. 1–12 (part one of the Gospel story). Verses 12–13 point to the adoption and acceptance of the disciples as the children of God in chs. 13–21 (part two of the story). Something of the whole plot of John’s story is therefore indicated at this stage.26

With respect to the theme of knowing and being known by Christ, the prologue anticipates the rest of the Gospel in predicting that even though “he was in the world, and the world came into being through him; yet the world did not know him” (John 1:10 NRSV). The fact that the Word made the world (see also 1:3) implies that he knew the world, something that is confirmed explicitly elsewhere in John in two places. To explain Jesus’s reluctance to entrust himself to certain people who had supposedly put their trust in him, the narrator explains that Jesus “knew all people” (2:24). And in a conversation with Peter, the risen Jesus asks Peter three times whether he loves him. The third time, Peter replies with some exasperation: “Lord, you know all things; you know that I love you” (21:17). But Jesus’s knowledge of others is not usually reciprocated, as many scenes throughout John attest; Jesus’s true identity was hidden from many of the characters with whom he interacts: “The world did not know him” (1:10 NRSV).

Nonetheless, according to the climax of the prologue, the purpose of the Word becoming flesh was to make himself and God known: “No one has ever seen [or known] God, but the one and only Son, who is himself God and is in closest relationship with the Father, has made him known” (1:18). To be known by and to come to know Jesus as the light of the world (1:9) is to be given “the right to become children of God” (1:12), the same personal identity that we have been exploring in this chapter and explored in chapter six in connection with being known by God.

The purpose statement of the Gospel of John makes clear that John’s overall goal is that readers might come to know the true identity of Jesus:

Jesus performed many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not recorded in this book. But these are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name. (John 20:30–31)

Combined with the prologue, John’s purpose is summed up as having his readers come to know Jesus as Messiah and Son of God and to know themselves as children of God (1:12). With reference to having “life in his name,” it is significant that elsewhere Jesus explains that to know God and himself is the equivalent of eternal life: “Now this is eternal life: that they know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom you have sent” (17:3).

Cumulative Reading

A second recommendation for reading John is not to read the Gospel in piecemeal fashion. For any passage in John, the context is the entire Gospel, which is framed by the prologue and purpose statement. The best way to read John is to read cumulatively, recalling what has gone before, and on second and subsequent readings anticipating what follows in the Gospel. Reading a narrative like John is thus a process of retrospection and prospection, looking back and looking forward across the book and making connections. As I tell students, read like a snowball rather than a bowling ball!

“Whenever we read past segments must be retained in each present moment. The new moment is not isolated, but stands out against the old, and so the past will remain as a background to the present, exerting influence on it and, at the same time, itself being modified by the present. . . . Reading does not merely flow forward, but recalled segments also have a retroactive effect, with the present transforming the past.”

Wolfgang Iser27

Known by Christ in John

The most significant passages in John for the topic of personal identity are those in which Jesus has an extended conversation with an individual. Richard Bauckham notes that there are seven such encounters, and they “represent a distinctive feature of John’s Gospel, one of its many differences from the Synoptics”:

1. Nathanael (1:47–51)

2. Nicodemus (3:1–21)

3. The Samaritan woman (4:7–26)

4. Martha (11:20–27)

5. Pilate (18:33–19:12)

6. Mary Magdalene (20:14–17)

7. Peter (21:15–22).28

There are several ways in which these conversations can be studied. These include how they contribute to the larger narrative in John; the manner in which the individuals are representative of larger groups (the Samaritan woman, her village; Nicodemus, the Jewish establishment; Martha, her family; and so on); how they draw readers to identify with the characters in question; and the way in which some of the characters are models of faith.

For our purposes they illustrate the theme of individuals being known by Jesus. Indeed, the distinctive manner in which Jesus interacts with the individuals concerned shows that Jesus knows them from the start. As Bauckham observes:

It is not only, as has so often been noticed, that they respond differently to Jesus, but that Jesus deals with each of them differently, according to their individual circumstances. Sometimes he initiates the dialogue, as, for example, rather shockingly in the case of the Samaritan woman, or tenderly, as a familiar friend, in the case of Mary Magdalene. Sometimes he responds to an approach, as with Nicodemus or Pilate. He does not deal with them according to some standard formula, but rather engages the particular point in their lives at which he encounters them. . . . The particularities of each encounter determine the themes of the dialogues, different in each case.29

The seven individuals relate very differently to Jesus. If Nicodemus is his Jewish interrogator and Pilate is his gentile judge, Martha, Mary Magdalene, and Peter are Jesus’s disciples, and Nathanael and the Samaritan woman become his disciples during their conversation with Jesus. We will focus on three who demonstrate Jesus’s intimate and personal knowledge of individuals who are among those who received him (John 1:12), namely, Nathanael, the Samaritan woman, and Mary Magdalene.

In a fourth section following the exposition of Jesus’s conversations with Nathanael, the Samaritan woman, and Mary Magdalene, we will focus on the Good Shepherd discourse in John 10 as the hermeneutical key to the theme of being known by Jesus in John’s Gospel. In each of the three cases, we will observe how Jesus’s comparison of himself to a shepherd in John 10 explains his profound personal knowledge of his followers. Jesus “calls his own sheep by name and leads them out” (John 10:3b). Speaking of himself, Jesus says: “I am the good shepherd; I know my sheep and my sheep know me” (10:14).

Jesus and Nathanael

The immediate context for Jesus’s conversation with Nathanael in John 1:47–51 is 1:19–46, the unit immediately following John’s prologue. The passage is characterized by an interest in questions of the personal identity of John the Baptist and Jesus, and also of his earliest followers.

In John 1:20 John the Baptist confesses to the delegation from the Jewish leaders in Jerusalem that he is “not the Messiah.” This prompts them to ask him, “Then who are you?” (1:21), and “What do you say about yourself?” (1:22). He replies cryptically that he is “the voice of one calling in the wilderness” (1:23) and then shifts the focus to the identity of someone else, namely, “the one who comes after me” (1:27).

The identity of Jesus takes center stage in the rest of the chapter. In fact, the Gospel of John is frontloaded with a veritable cascade of answers to the question, who is Jesus? John the Baptist confesses: “I myself did not know him” (1:33). However, Jesus’s identity was revealed to John by God at Jesus’s baptism when the Spirit descended on Jesus like a dove. On that basis, John the Baptist identifies Jesus as “the Lamb of God” (1:29, 36) and “God’s Chosen One” (1:34). In the rest of the chapter, other characters also reveal Jesus’s identity:

• Andrew calls Jesus “the Messiah (that is, the Christ)” (1:41).

• Philip describes Jesus as “the one Moses wrote about in the Law, and about whom the prophets also wrote” (1:45).

• Nathanael declares to Jesus “you are the Son of God; you are the king of Israel” (1:49).

• Jesus calls himself “the Son of Man” (1:51).

John 1:11–12 ◂ John 1:35–51

The identity of Jesus’s disciples is also a focus in John 1:35–51. As D. A. Carson explains, “the chapter provides concrete examples of a point made in the prologue: although in general his own people did not receive him, yet some did, believing on his name and gaining from him the authority to become children of God (1:11–12).”30 First of all, we are introduced to Andrew and his brother Simon Peter, whom Jesus renames Cephas (1:40–42). This action looks forward to John 10:3 where Jesus explains that “he calls his own sheep by name.”

Next in line for introductions are Philip and then Nathanael. Nathanael’s experience illustrates what it means to know and be known by Jesus:

When Jesus saw Nathanael approaching, he said of him, “Here truly is an Israelite in whom there is no deceit.”

“How do you know me?” Nathanael asked.

Jesus answered, “I saw you while you were still under the fig tree before Philip called you.”

Then Nathanael declared, “Rabbi, you are the Son of God; you are the king of Israel.” (John 1:47–49)

Jesus sees Nathanael and offers a brief summary of his character: he is truly an Israelite “in whom there is no deceit” (1:47). The description itself calls to mind a passage in the Old Testament. In Genesis 28:10–15 and 32:24–30, Jacob is called Israel after encounters with God that transform his devious character. Jesus recognizes that Nathanael is an “Israel” not a “Jacob.”

Nathanael’s question “How do you know me?” in John 1:48 confirms that Jesus’s assessment of him is accurate. Jesus replies that he simply saw him under the fig tree. What Nathanael was doing under the fig tree is open to conjecture: “In the Old Testament the fig tree is sometimes almost a symbol for ‘home’ or for prosperity (e.g. 1 Ki. 4:25; Is. 36:16; Zc. 3:10); occasionally in rabbinic literature its shade is associated with a place for meditation and prayer.”31 However, the point is not Nathanael’s location so much as Jesus’s precise and penetrating knowledge of Nathanael. Jesus knew him before he had even met him.

John 1:49 ▸ John 20:31

In response to being known by Jesus, Nathanael declares Jesus’s own identity with remarkable clarity: “you are the Son of God; you are the king of Israel” (John 1:49). If Jesus’s knowledge of Nathanael points back to the prologue’s prediction that some will receive him (1:12), Nathanael’s confession points forward to the Gospel’s purpose statement. John wrote that his readers might come to know Jesus as “the Messiah, the Son of God” (20:31). As Andrew Lincoln observes, “Nathanael’s believing confession is in line with the Gospel’s statement of purpose (see also 20:31).”32 Not only does Nathanael know Jesus as “the Son of God,”33 his confession that Jesus is “the king of Israel” is equivalent to calling him “the Messiah” since “the title King of Israel was used by Palestinian Jews for the Messiah.”34 In John the titles “Son of God” and “Messiah” or its equivalents (“Christ” or “King of Israel”) only occur together in 1:49 and 20:31.

From the Nathanael episode in John 1:47–49, we learn that Jesus’s piercing knowledge of his own is prior to and elicits their accurate knowledge of him. Jesus knows us before we know him and knows much better than we will ever know him.

John 1:16 ◂ John 1:51

Nathanael’s conversation with Jesus and confession of Jesus as God’s Son and King is not merely for his own benefit. Being known by Jesus turns Nathanael into a disciple of Jesus. And as we will see with the Samaritan woman and Mary Magdalene, others benefit when we enter into a living relationship with Jesus.

In John 1:50–51 Jesus moves from addressing Nathanael alone to addressing the group of disciples. Notice the change from singular to plural Greek pronouns in Jesus’s final words to Nathanael:

Jesus said, “You [singular] believe because I told you [singular] I saw you [singular] under the fig tree. You [singular] will see greater things than that.” He then added, “Very truly I tell you [plural], you [plural] will see heaven open, and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man.”

John 1:51 is the climax of John 1:19–51. It is the first time Jesus teaches in John. It is the first of many times that Jesus refers to himself as “the Son of Man” in John. And it is the first of twenty-five sayings introduced with the solemn words, “Very truly I tell you.” The words “you will see heaven open, and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man” are an allusion to Jacob’s dream in Genesis 28:12: “he saw a stairway resting on the earth, with its top reaching to heaven, and the angels of God were ascending and descending on it.”

All Jews acknowledged Jacob/Israel, the father of the twelve tribes, as one who had received a critical revelation from God. In John 1:51 we learn that Jesus replaces and surpasses that revelation. He bridges heaven and earth. As John 1:16 says, “Out of his fullness we have all received grace in place of grace already given.” Carson writes: “What the disciples are promised, then, is heaven-sent confirmation that the one they have acknowledged as the Messiah has been appointed by God.”35

Jesus and the Samaritan Woman

John 4 contains another example of Jesus knowing someone deeply and that knowledge leading this person to a saving knowledge of him. The passage in question is known for several things, not least Jesus’s evocative promise of “living water. . . . welling up to eternal life” (4:10, 14). For our purposes, the passage deals with questions of the identity of both Jesus and a potential follower.

In John 4:1–7, Jesus arrives in Sychar, a town in Samaria, where he meets a Samaritan woman. Jesus meets her at Jacob’s well and asks her to draw water for him to drink (4:6–7). Focusing on his ethnic and religious identity, she is reluctant, pointing out that Jews do not associate with Samaritans (4:9). Jesus runs with the subject of his own identity and counters that if she “knew who it is that asks you for a drink” (4:10), she would have asked him for a drink!

John 2:24 ◂ John 4:17–19 ▸ John 6:70–71

The two then talk at cross-purposes about wells and springs of water before Jesus tells her to “go, call your husband and come back” (4:16). She replies concerning her marital status that she has no husband (4:17a). Jesus’s responds unnervingly: “You are right when you say you have no husband. The fact is, you have had five husbands, and the man you now have is not your husband. What you have just said is quite true” (4:17b–18).

That Jesus has supernatural insight into the character of people is also attested in two other places in the Gospel. In John 2:24–25 it is affirmed that Jesus “knew all people” and that “he knew what was in each person.” And in John 6:70–71 Jesus predicts his betrayal by Judas: “Have I not chosen you, the Twelve? Yet one of you is a devil!” (6:70).

Jesus’s precise knowledge of her past understandably prompts the woman to reflect on his identity. She responds, “I can see that you are a prophet” (4:19). While grammatically it is possible that she meant that Jesus was the coming prophet like Moses (see Deut 18:15–19), a title for the Messiah, she probably meant no more than “prophet” in the sense of someone with a special gift of insight. (As John 4:25–26 indicates, she comes to know Jesus as the Messiah at a later point in the conversation.)

John 4:25–26, 28 ▸ John 20:30–31

Having demonstrated his keen knowledge of the woman, Jesus finally reveals to her that he is in fact the long-awaited Messiah: “I, the one speaking to you—I am he” (4:26). Like Nathanael, being known by Jesus led to knowing Jesus and being useful to him as a disciple and witness. The woman returned to the town in exuberant astonishment: “Come, see a man who told me everything I ever did. Could this be the Messiah?” (4:29). The result of her testimony to Jesus’s identity was that those to whom she spoke “came out of the town and made their way towards him” (4:30).

Just as in John’s purpose statement, the promise of life is premised on believing that Jesus is the Messiah: “whoever drinks the water I give them will never thirst. Indeed, the water I give them will become in them a spring of water welling up to eternal life” (John 4:14). Jesus’s encounter with the Samaritan woman serves as a case study of his deep knowledge of an individual leading to mutual positive recognition. Being known by Jesus leads to knowing Jesus the Messiah. And in the context of John 4, as identities go, being known by Jesus and knowing Jesus as Messiah is of greater significance for a person’s identity than that individual’s own ethnicity (Jew or Samaritan) and marital status (married or divorced):

A time is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem. . . . a time is coming and has now come when the true worshipers will worship the Father in the Spirit and in truth. (John 4:21, 23a)

Jesus and Mary Magdalene

The third extended conversation in John in which an individual is known by Jesus is the post-resurrection appearance of Jesus to Mary Magdalene outside the garden tomb. A climactic scene in the Gospel, Mary is the first person in John to encounter the risen Jesus and also the first to proclaim to others the good news of the resurrection. The passage opens with a focus on Mary’s grief:

Now Mary stood outside the tomb crying. As she wept, she bent over to look into the tomb and saw two angels in white, seated where Jesus’ body had been, one at the head and the other at the foot.

They asked her, “Woman, why are you crying?”

“They have taken my Lord away,” she said, “and I don’t know where they have put him.” (John 20:11–13)

Mary’s tears are mentioned four times; twice by the narrator (20:11), once by the angels (20:13), and once by Jesus (20:15). The tender pathos of the scene is unmistakable. Jesus comes to Mary and knows her in her time of sorrow and despair. Bauckham makes the intriguing suggestion that “Jesus’s encounter with Mary Magdalene in the garden is intended to recall Isaiah 25:8”: “He will swallow up death forever. The Sovereign LORD will wipe away the tears from all faces.”36

John 1:38 ◂ John 7:34 ◂ John 20:15

At this point Jesus engages Mary in conversation:

At this, she turned around and saw Jesus standing there, but she did not realize that it was Jesus. He asked her, “Woman, why are you crying? Who is it you are looking for?” (John 20:14–15a).

The Greek verb “to look for” (zēteō) in v. 15a is often translated “to seek” in other parts of John. As it turns out, there is a lot of “seeking” in the Gospel. The “search” begins in John 1:38 where Jesus asks Andrew and Philip, “What do you seek?”37 Their answer is given in 1:41, “We have found the Messiah,” and in 1:45, “We have found the one Moses wrote about in the Law, and about whom the prophets also wrote.”

The successful “seeking” of Andrew and Philip contrasts with that of the Jewish leaders, about whom Jesus lamented, “You will seek me, but you will not find me” (John 7:34). Up until Mary’s “search” in John 20:15a, “most examples of people seeking Jesus in the Gospel show them doing so for wrong or inadequate reasons.”38 When it comes to the theme of seeking Jesus in John, the Gospel opens with Jesus asking Andrew and Philip, “What do you seek?” (1:38), and it closes with Jesus asking Mary, “Whom do you seek?” (20:15). As Bauckham notes, in John “only the last occurrence of the verb [“to seek”] corresponds to the first.”39 In both cases “what is found exceeds what is sought.”40 They find the Messiah who loves them and lays down his life for them (John 10:11).

John 10:3–4 ◂ John 20:16

The two questions from Jesus are not enough for Mary to recognize him. In fact in John 20:15b, she mistakes him for someone else:

Thinking he was the gardener, she said, “Sir, if you have carried him away, tell me where you have put him, and I will get him.”

To clear up the misunderstanding, Jesus utters a single word, Mary’s name:

Jesus said to her, “Mary.” She turned toward him and cried out in Aramaic, “Rabboni!” (which means “Teacher”). (John 20:16)

Don Carson draws out the significance of this exquisite moment and makes a connection to the Good Shepherd discourse in John 10:

Whatever the cause of her blindness, the single word Mary, spoken as Jesus had always uttered it, was enough to remove it. The good shepherd “calls his own sheep by name . . . and his sheep follow him because they know his voice” (10:3–4). Anguish and despair are instantly swallowed up by astonishment and delight.41

Mary answers Jesus in her customary manner, “Rabboni,” indicating her relationship to Jesus as his disciple and acknowledging his authority. As Lincoln notes, “the first disciples had responded to Jesus’s question in 1:38 by calling him Rabbi, and Rabboni is an extended form of this address.”42 Jesus knows those who belong to him intimately and personally; he knows them by name.

“It is the human tenderness of Jesus’s love for his friends that John’s exquisitely told narratives are able to evoke as nothing else could. We see it incomparably in the story of his meeting with Mary Magdalene in the garden (20:11–18). It is a reunion of friends, the reunion that Jesus had promised his friends after his supper (16:16–22). For Jesus, it is a reunion with one of only four friends who stood by him in the extremity of his giving his life for them (19:25–26). Moreover, very significantly, the encounter echoes the parable of the good shepherd. Like the sheep in the parable (10:3, 14), Mary recognizes Jesus’s voice when he says her name. She is one of his own who knows him personally, as he knows her.”

Richard Bauckham43

John 1:12 ◂ John 20:17

This “touching” scene continues with Jesus insisting that Mary not touch him. Their intimacy and friendship will have to continue in a different form in the light of his resurrection:

Jesus said, ‘Do not hold on to me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father. Go instead to my brothers and tell them, “I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God.” (John 20:17)

Jesus’s response to Mary contains a hint of what he has done for her in laying down his life (John 10:11): his Father is now her Father, and his God, hers! John has around one hundred and twenty references to God as the Father of Jesus, and this is the only one where that filial relationship is extended to his disciples.

Throughout the Gospel, Jesus’s relationship to his Father has been a constant focus and, at times, a bone of contention (see John 10:30). And that relationship has been exclusive; even his disciples have not shared in it and do not address God as Father. But back in the prologue in John 1:12, it was promised that all who believe in Jesus’s name would be given “the right to become children of God.” Jesus’s words to Mary indicate the fulfillment of that promise. In John 20:15–17 this new identity as a child of God is tied up with being known by Jesus.

As with Nathanael and the Samaritan woman, being known by Jesus leads to Mary being enlisted in his service. She immediately goes and proclaims the resurrection of Jesus from the dead:

Mary Magdalene went to the disciples with the news: “I have seen the Lord!” And she told them that he had said these things to her. (John 20:18)

Jesus and His Sheep

Three times in John, Jesus surprises individuals with his intimate and personal knowledge of them. Nathanael asks in bewilderment: “How do you know me?” (1:48). The Samaritan woman exclaims in amazement: “I can see that you are a prophet” (4:19). And Mary Magdalene turns to embrace Jesus when he addresses her by name (20:16). In each case, being known by Jesus led to knowing Jesus and remarkable confessions about his identity. And in each case, being known by Jesus led to Jesus being known by others.

| Individual | Known by Jesus | Knowing Jesus | Others Know Jesus |

| Nathanael | Jesus knows his character to be without guile | “the Son of God” and “the king of Israel” | All of the disciples will receive a revelation of Jesus’s true identity |

| The Samaritan Woman | Jesus knows her personal history | “the Messiah” | Many Samaritans respond to her witness and acknowledge Jesus as “the Savior of the world” |

| Mary Magdalene | Jesus calls her by name | “Rabboni” and “Lord” | She tells the disciples that the Lord is risen |

The cycle of evangelism can be conceived of as a two-step process: people come to know Jesus and then make him known to others. However, this cycle misses a crucial first step that makes the other two steps possible. These three conversations of Jesus with individuals in John teach us that being known by Jesus leads to knowing him and making him known. And being known by Jesus is the critical and initial step in the process.

How are we to understand Jesus’s extraordinary and transforming knowledge of his disciples? The parable of Jesus as the Good Shepherd in John 10 provides a good explanation.44 In John 10:1–21 Jesus tells a parable of sheep and shepherds to teach about the relationship between the people of God and their leaders. His purpose is not only to depict his own role as the true leader of God’s people but also to criticize the behavior of the Pharisees toward the blind man whom Jesus had healed in John 9. If Jesus is the Good Shepherd (10:11, 14), the Pharisees are the thieves and robbers who climb into the sheep pen and do not use the gate (10:1). The passage opens with Jesus addressing the Pharisees (10:1) and closes with a reference to Jesus’s healing of the blind man (10:21b). The stark contrast between Jesus’s leadership and that of the Pharisees is also underscored by the repetition of the Greek verb “to send out,” ekballō:

In John 9:34 the Pharisees “send out” or “throw out” of the synagogue the man who was born blind and had been healed by Jesus.

In John 10:4 Jesus “sends out” or “brings out” of the sheep pen “all his own,” lovingly going before them.

The picture that Jesus paints in John 10 is one of several flocks of sheep in a fold. Shepherds in the ancient Near East were known to stand in a familiar place and call to their sheep in such folds. The sheep would then recognize their own shepherd’s voice and gather around him. In the parable Jesus goes a step further and calls his sheep by name:45

The gatekeeper opens the gate for him, and the sheep listen to his voice. He calls his own sheep by name and leads them out. When he has brought out all his own, he goes on ahead of them, and his sheep follow him because they know his voice. (John 10:3–4)

It is not only Nathanael and Mary Magdalene whom Jesus knows by name; the same is true for all who are “his own” (10:4), those who belong to him.46

In the flow of John’s narrative, the parable teaches that Jesus comes to the sheep pen of Judaism and “calls his own sheep out individually to constitute his own messianic ‘flock.’ ”47 However, Jesus has others in mind also; we are not merely spectators when it comes to being known by Jesus. Jesus also addresses the readers of the Gospel to reassure them that the same intimate, mutual knowing and loving relationship applies to them if they believe in Jesus: “I have other sheep that are not of this sheep pen” (10:16). John 17:20 strikes a similar note: “My prayer is not for them alone. I pray also for those who will believe in me through their message.”

The parable goes on to compare the relationship of Jesus to his sheep to the relationship of Jesus to God:

I am the good shepherd; I know my sheep and my sheep know me—just as the Father knows me and I know the Father—and I lay down my life for the sheep. (John 10:14–15)

The key clauses of the passage form a chiastic structure, where the first and fourth elements correspond to each other, as do the second and third:

| A | I know my sheep and |

| B | my sheep know me—just as |

| B1 | the Father knows me |

| A1 | and I know the Father— and I lay down my life for the sheep. |

Jesus’s relationship with his Father illustrates the shape and nature of his relationship with his sheep; he knows them “just as” the Father knows him. Unlike the Pharisees, Jesus knows the people of God intimately and personally. The relationship of mutual knowing that believers have with Jesus is modeled on the relationship of mutual knowing of Jesus and his Father.48 Or as Don Carson puts it, the intimacy of the relationship between Jesus and his sheep is “grounded upon the intimacy between the Father and the Son.”49 The language of Father and Son knowing each other underscores the closeness of their relationship. The passage also links Jesus’s knowledge of his sheep with his care for his sheep. He is willing to die for them, unlike a Pharisee who “abandons the sheep and runs away” if any danger arises (John 10:11–12, 15).

“The love between the Father and the Son, their unsurpassable intimacy, is the source from which relationship between God and humans derives.”

Richard Bauckham50

The intimacy of Jesus’s relationship to his Father is in fact introduced in John’s prologue where 1:18 says that the Son is “in the bosom of the Father” (KJV), meaning “near the Father’s heart” (NLT). Significantly, a similar expression is used of the beloved disciple’s closeness to Jesus at the Last Supper: “Now there was leaning on Jesus’ bosom one of his disciples, whom Jesus loved” (John 13:23 KJV). The same thing is said of the intimacy of Jesus’s relationship to his Father and of Jesus’s intimacy with his disciples. Jesus is close to God’s heart, and we are close to his.

Being known by Jesus produces an intimate and abiding relationship between Jesus and the individual believer modeled on the relationship of Jesus and his Father. John’s Gospel develops this notion with its profound teaching about what Bauckham calls the “in-one-anotherness” or “personal coinherence”51 between individual believers and Jesus, which is also modeled on the Father and the Son being in one another. This language, along with the notes of mutual knowing, underscores the special bond that exists between two persons.

A few texts highlight the extraordinary closeness of the Father and the Son with in-one-another language:

The Father is in me, and I in the Father. (John 10:38)

Don’t you believe that I am in the Father, and that the Father is in me? (John 14:10)

The parable of the vine and branches in John 15, on the other hand, teaches a reciprocal in-one-another relationship for believers and Christ:

Remain in me, as I also remain in you. (15:4; see also 15:5, 7)

In terms reminiscent of John 10:14–15, Jesus sums up the analogous nature of this mutual indwelling in John 14:20:

I am in my Father, and you are in me, and I am in you.

BEING KNOWN BY GOD AND CHRIST AND PERSONAL IDENTITY

According to the Bible, in order to know who you are, you have to know whose you are. We are defined by our relationships, by who we know, and who knows us. And when it comes to personal identity, both the Old and New Testaments agree that being known by God is of critical importance. Being known by God introduces a new belonging. We belong to God as his children. We are part of his family. But the New Testament brings that relationship into sharper focus. We are not only known by God, but also known by Jesus Christ.

Does Jesus Christ know you intimately and personally? Does he know your personality, your character, and your particular circumstances? Does he know you by name? As Bauckham notes, three remarkable conversations in John’s Gospel between Jesus and Nathanael, the Samaritan woman, and Mary Magdalene “encourage hearers or readers to expect Jesus to meet them and direct them in the particularity of their individual lives and circumstances.”52 The three conversations are recorded so that we might know that we too are known by Jesus, just as intimately as the Father knows the Son and the Son knows the Father.

Eustace asked Edmund: “Do you know him?” He replied: “Well, he knows me. He is the great Lion, the son of the Emperor-beyond-the-Sea, who saved me and saved Narnia.”53

If you were to ask Nathanael, the Samaritan woman, and Mary Magdalene if they knew Jesus, they might have replied: “Well, he knows me. And he is the Messiah, the Son of God, and by believing in him we have life in his name.”

To be known by Jesus is to come to know Jesus as God’s Son and King (John 20:30–31) and to be given a new identity as his disciple and as God’s child. The connections between belonging to Jesus, being known by Jesus, and being a child of God are evident when texts from John 1, 10, and 20 are compared:

| To all who did receive him, to those who believed in his name, he gave the right to become children of God. (John 1:12) | “He calls his own sheep by name. . . . I know my sheep and my sheep know me.” (John 10:3b, 14) |

Jesus said to her, “Mary”. . . . “I am ascending to my Father and your Father.” (John 20:16, 17) |

John Calvin wrote that the conversation with Mary Magdalene in John 20 is a model for what all believers can expect from Jesus Christ:

Jesus had formerly addressed her, but his discourse seemed to be that of an unknown person; he now assumes the character of the Master, and addresses his disciple by name, as we have formerly seen that the good shepherd calls to him by name every sheep of his flock (John 10:3). That voice of the shepherd, therefore, enters into Mary’s heart, opens her eyes, arouses all her senses, and affects her in such a manner, that she immediately surrenders herself to Christ. Thus in Mary we have a lively image of our calling; for the only way in which we are admitted to the true knowledge of Christ is, when he first knows us, and then familiarly invites us to himself, not by that ordinary voice which sounds indiscriminately in the ears of all, but by that voice with which he especially calls the sheep which the Father hath given to him. Thus Paul says, “After that you have known God, or rather, after that you have been known by him” (Gal 4:9).54

The New Testament expands the theme of being known by God to being known not only by God but also by Jesus Christ. To the church in Sardis Jesus wrote:

The one who is victorious will, like them, be dressed in white. I will never blot out the name of that person from the book of life, but will acknowledge that name before my Father and his angels. (Rev 3:5)

If earlier in this chapter we noted the dark and gloomy verdict of not being known by Jesus at the last judgment, here we read of the sublimely joyful occasion of being known by name by both Jesus and God.55 As N. T. Wright observes: “To be acknowledged by Jesus himself will be amazing. To have him acknowledge us before his father will be the moment of all moments.”56

RELEVANT QUESTIONS

1. The idea that “the Lord knows those who are his” is a solid and firm foundation upon which believers can confidently build their lives (2 Tim 2:19). Does this reflect the way you currently live? Or do you find this a challenge? Why?

2. How is our personal identity tied up with Jesus Christ and his identity?

3. All the letters to the churches in Asia Minor (Rev 2–3) include the phrase “I know.” If Jesus were to write you a similar letter stating “I know,” what might he write about you? How do you feel about the fact that Jesus knows you intimately and personally?

4. Contrast the leadership of Jesus (particularly shown in the parable of the Good Shepherd) with the leadership of the Pharisees. What difference does his deep and transforming knowledge of us make?

5. Have you ever considered that the way we are known by Jesus is modeled on the extraordinary closeness between the Father and the Son? How does this idea of “mutual knowing” help us to work out who we are?

1. C. S. Lewis, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (London: Lions, 1980; orig. 1955), 87. Emphasis added.

2. F. F. Bruce, The Epistle to the Galatians: A Commentary on the Greek Text, NIGTC (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982), 202.

3. See Ernest de Witt Burton on the phrase: “Following a positive expression it introduces an additional and more important fact or aspect of the matter, not thereby retracting what precedes, but so transferring the emphasis to the added fact or aspect as being of superior significance as in effect to displace the preceding thought” (A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians, ICC [Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1921], 229). See also Rom 8:34; 1 Cor 14:1, 5; Eph 4:28; 5:11.

4. See Hans Conzelmann, 1 Corinthians: A Commentary on the First Epistle to the Corinthians, ed. George W. MacRae, trans. James W. Leitch, Hermeneia (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1975), 141. See also Richard B. Hays: “We expect: ‘The person who loves God, knows him rightly.’ But the thought is deliberately given a different turn” (First Corinthians, Interpretation [Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1997], 139).

5. Augustine, Confessions (London: Penguin, 1961), 207.

6. The passive voice of the Greek verb “to know” is used here with God as the obvious, but implicit agent of the action (often labeled a divine passive).

7. C. K. Barrett, The First Epistle to the Corinthians, BNTC (London: Black, 1971), 307.

8. Gunther Bornkamm, “The More Excellent Way,” in Early Christian Experience (New York: Harper & Row, 1969), 185.

9. Barrett, First Epistle to the Corinthians, 334.

10. Another divine passive; see footnote on 1 Cor 13:12 above.

11. Hays, First Corinthians, 244.

12. See D. A. Carson, Showing the Spirit: A Theological Exposition of 1 Corinthians 12–14 (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1996), 133.

13. The standard lexicon for New Testament Greek translates the verb in question, agnoeō, as “to disregard,” “to ignore,” and “not to know” (BDAG 12–13).

14. BDAG 866.

15. The NIV translates the Greek huioi as “children” instead of “sons” in 3:26 and 4:4–7 to indicate that the term in context is gender inclusive; it refers to both male and female believers in Christ. While this is true in the present discussion, I prefer “sons” to preserve the technical distinction between children and sons, the latter in the ancient world being heirs with full rights (see 4:7). The difference between children and sons will be further clarified in chapter eight.

16. Timothy George, Galatians: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture, NAC 30 (Nashville: Broadman & Holman, 1994), 314.

17. George R. Beasley-Murray, “Book of Revelation,” in Dictionary of the Later New Testament and Its Developments, ed. R. P. Martin and P. H. Davids, electronic ed. (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1997), 1030.

18. N. T. Wright, Revelation for Everyone (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 2011), 23.

19. Ian Boxall, The Revelation of Saint John, BNTC (London: Continuum, 2006), 61. The reference to a new name in Rev 2:17 remains obscure. The consensus among biblical commentators is still that “we simply do not know what the white stone signified, though clearly it did convey some assurance of blessing” (Leon Morris, The Book of Revelation, TNTC (Leicester, UK: Inter-Varsity Press, 1987), 68.

20. See also Rev 3:12: “The one who is victorious I will make a pillar in the temple of my God. Never again will they leave it. I will write on them the name of my God and the name of the city of my God, the new Jerusalem, which is coming down out of heaven from my God; and I will also write on them my new name.”

21. See Deut 8:5: “Know then in your heart that as a man disciplines his son, so the LORD your God disciplines you”; Prov 3:12: “the LORD disciplines those he loves, as a father the son he delights in”; see also Heb 12:5–6 which quotes Prov 3:11–12.

22. Wright, Revelation for Everyone, 27.

23. See also Ps 9:4–6: “For you have upheld my right and my cause, sitting enthroned as the righteous judge. You have rebuked the nations and destroyed the wicked; you have blotted out their name for ever and ever. Endless ruin has overtaken my enemies, you have uprooted their cities; even the memory of them has perished.”

24. G. K. Beale states, “Christ will confess the names of believers to his Father and to the angels. The idea may be that he will read the believers’ names out of the book of life in recognition of their final salvation. . . . Those who confess Christ’s name have their own name confessed by Christ before the Father” (The Book of Revelation, NIGTC [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999], 280–81).

25. W. D. Davies and D. C. Allison, Matthew 1–7, ICC (London: T &T Clark, 1988), 717.

26. Mark W. G. Stibbe, John (Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1993), 26.

27. Wolfgang Iser, The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978), 114, 116.

28. Richard Bauckham, Gospel of Glory: Major Themes in Johannine Theology (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2015), 14.

29. Bauckham, Gospel of Glory, 15–16. Emphases added.

30. D. A. Carson, The Gospel according to John, PNTC (Leicester, UK: Inter-Varsity Press, 1991), 157.

31. Carson, Gospel according to John, 161.

32. Andrew T. Lincoln, Gospel according to Saint John, BNTC (London: Continuum, 2005), 121.

33. Lincoln notes the startling nature of Nathanael’s knowing Jesus as “Son of God” when compared to the Synoptic Gospels: “Luke does not use ‘Son of God’ as a title addressed to Jesus by his followers; neither does Mark, though he has the title on human lips for the first time when the centurion witnesses Jesus’s death (Mark 15:39). Matthew also employs it in the centurion’s confession (Matt 27:54) but is willing to use it earlier in the disciples’ recognition of Jesus after he has walked on the water and in Peter’s confession at Caesarea Philippi (Matt 14:33; 16:16). John’s Gospel, however, has Jesus recognized by his followers as Son of God from the outset of his ministry and then develops this category as the key to understanding Jesus’s true identity” (Gospel according to Saint John, 121).

34. Carson, Gospel according to John, 161–62.

35. Carson, Gospel according to John, 163–64.

36. Bauckham, Gospel of Glory, 72.

37. My own translation.

38. Bauckham, Gospel of Glory, 148.

39. Ibid.

40. Ibid.

41. Carson, Gospel according to John, 64. See also Lincoln, “The revelation to Mary of Jesus’s identity takes place through the personal address with its utterance of her name, ‘Mary,’ in contrast to ‘Woman,’ which had introduced the previous questions. As the good shepherd, Jesus calls his own sheep by name, and Mary turns to face him directly because now she knows his voice (cf. 10:3–4)” (Gospel according to Saint John, 493). Murray J. Harris writes, “Jesus proceeds to call one of his sheep by name (cf. 10:3)” ( John, Exegetical Guide to the Greek New Testament [Nashville: Broadman and Holman Academic, 2015], 327).

42. Lincoln, Gospel according to Saint John, 493.

43. Bauckham, Gospel of Glory, 68–69.

44. “I am the Good Shepherd” is one of seven “I am” sayings in John.

45. Bauckham, Gospel of Glory, 69. Bauckham notes, “John 10:3 is the only reference in the Bible to animals having names.”

46. The same language is used in 3 John 14 in the context of personal relationship and friendship: “Greet the friends there by name.”

47. Carson, Gospel according to John, 383.

48. See also Luke 10:22: “No one knows who the Son is except the Father, and no one knows who the Father is except the Son and those to whom the Son chooses to reveal him.”

49. Carson, Gospel according to John, 387.

50. Bauckham, Gospel of Glory, 19.

51. Bauckham’s terms; see Gospel of Glory, 11.

52. Bauckham, Gospel of Glory, 17.

53. Lewis, Voyage of the Dawn Treader, 87.

54. John Calvin and William Pringle, Commentary on the Gospel according to John, vol. 2 (Bellingham, WA: Logos Bible Software, 2010), 257–58.

55. See also Matt 10:32: “Whoever acknowledges me before others, I will also acknowledge before my Father in heaven.”

56. Wright, Revelation for Everyone, 32.